Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Search For Elusive Structure: A Promiscuous Realist Case For Researching Specific Psychotic Experiences Such As Hallucinations

Uploaded by

Susana Campos SotoOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Search For Elusive Structure: A Promiscuous Realist Case For Researching Specific Psychotic Experiences Such As Hallucinations

Uploaded by

Susana Campos SotoCopyright:

Available Formats

Schizophrenia Bulletin vol. 40 suppl. no. 4 pp.

S198S201, 2014

doi:10.1093/schbul/sbu044

The Search for Elusive Structure: A Promiscuous Realist Case for Researching

Specific Psychotic Experiences Such as Hallucinations

Richard P.Bentall*,1

School of Psychological Sciences, Institute of Psychology, Health and Society, University of Liverpool, Liverpool, UK

*To whom correspondence should be addressed; School of Psychological Sciences, Institute of Psychology, Health and Society,

University of Liverpool, Liverpool L69 3GL, UK; tel: +44-151-795-5367, e-mail: richard.bentall@liverpool.ac.uk

Key words: hallucinations/diagnosis/schizophrenia

The past three decades have seen a steady increase in

the volume of research on psychotic phenomena. In the

early 1980s, publications on symptoms were rare (36

papers with hallucinations in their titles were published in 1983 with a cumulative number of 1630 papers

until that time; Google Scholar, accessed February

14, 2014). Thirty years later, research on symptoms is

more vibrant (336 papers with hallucinations in their

title published in 2013 with a cumulative total of 6320

papers). This development has been fueled by the invention of new research technologies (notably functional

magnetic resonance imaging) that have made symptoms

more tractable objects of scientific inquiry, and by a need

to understand underlying mechanisms prompted by the

emergence of novel interventions. In introducing this

Special Supplement on Hallucinations, I want to focus

on a third compelling reason for focusing research on

particular kinds of psychotic experience such as hallucinations: the apparently intractable problem of psychiatric classification.

Recent Attempts to Solve Problems of Psychiatric

Classification

Toward the end of the first century of schizophrenia

research, a few observers noted that broad diagnoses such

as schizophrenia were scarcely adequate as independent

variables in research because they were defined inconsistently, failed to cleave nature at its joints, and grouped

together problems which probably had little in common.1,2 At the time this was a minority position. However,

the need for a nondiagnosis-based research strategy has

become much more widely accepted in the intervening

years, most notably among biological researchers such

as geneticists,3 and pharmacologists,4 leading NIMH to

recently propose the Research Domain Criteria (RDoC)

approach.5 This debate has not been resolved by the publication of successive editions of the DSM6 and, indeed,

seems to have intensified with the publication of DSM-5

which, claims to the contrary notwithstanding, has

achieved poor reliability in field trials.7

One solution to this problem is to attempt to develop

empirically based classification systems. Two proposals appear to be gaining traction at the time of writing.

First, analyses of patterns of comorbidity between different diagnoses suggest that the common psychiatric

conditions fall into 2 broad spectra of internalizing and

externalizing disorders, the former subdividing into anxious misery and fear and the latter including conduct

and substance abuse disorders.8 A large international

study of nonpsychotic DSM-defined disorders9 recently

found considerable comorbidity within the spectra (eg,

individuals who met the criteria for depressionan internalizing disorderhad a high probability of meeting

the criteria for generalized anxiety, also an internalizing

disorder) but not across the spectra. Interestingly, there

was no particular order of acquisition when comorbidity

occurred (eg, some people became anxious before they

became depressed and vice versa). Recent studies have

The Author 2014. Published by Oxford University Press on behalf of the Maryland Psychiatric Research Center.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/), which

permits unrestricted reuse, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

S198

Downloaded from http://schizophreniabulletin.oxfordjournals.org/ at UTALCA on August 5, 2014

Problems in psychiatric classification have impeded

research into psychopathology for more than a century.

Here, I briefly review several new approaches to solving

this problem, including the internalizing-externalizing-psychosis spectra, the 5-factor model of psychotic symptoms,

and the more recent network approach. Researchers and

clinicians should probably adopt an attitude of promiscuous realism and assume that a single classification system

is unlikely to be effective for all purposes, and that different systems will need to be chosen for research into etiology, public mental health research, and clinical activities.

Progress in understanding the risk factors and mechanisms

that lead to psychopathology is most likely to be achieved

by focusing on specific types of experience or symptoms

such as hallucinations.

The Search for Elusive Structure

instructive. Nearly two and a half centuries after the death

of Carl Linnaeus, who devised the general approach to

biological classification, some observers have argued that

continuing disputes about how to define the boundaries

between species cannot be definitively resolved, so that

biologists should accept a doctrine of promiscuous realism.17 Adopting the same doctrine, psychopathologists

should perhaps accept that, while there is structure in the

way that symptoms co-occur, the structure is so complex

that a one size-fits-all method of classification cannot be

expected to suit all purposes. What works in etiological

research, for the purposes of investigating public mental

health and in the clinic may well be different.

Recognizing Complexity

When a problem seems intractable it is sensible to examine some of the underlying assumptions that have driven

past attempts to solve it. Borsboom18 reminds us that one

such assumption is that syndromes are caused by latent

entities. Hence, it is assumed that, if there is a cluster

of symptoms corresponding to the diagnosis of schizophrenia, this implies that schizophrenia is the cause

of the symptoms. This idea leads to the diagnosis being

employed as an independent variable when attempting to

investigate the etiology of psychiatric disorders. However,

structure may arise for many reasons and, as Borsboom

points out, is not always best interpreted as evidence of a

causal latent entity.

Developing this idea further, Borsboom and Cramer19

have proposed that syndromes can arise because symptoms create the conditions in which other symptoms are

likely to occur. To take the simplest example possible,

sleep problems and problems of concentration both

appear in lists of the symptoms of depression but this is

not because depression (a latent entity inferred from

the symptoms) causes both sleep problems and poor concentration but because sleep problems lead to problems

of concentration. Moreover, it is also no surprise that

depression and anxiety tend to be comorbid diagnoses

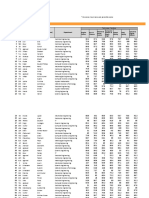

Fig.1. Speculative hierarchical partial classification of psychopathology, integrating the bifactor, internalizing-externalizing-psychosis,

and 5-factor models.

S199

Downloaded from http://schizophreniabulletin.oxfordjournals.org/ at UTALCA on August 5, 2014

extended this model to establish that the psychotic disorders appear to form a separate, third spectrum.10

Research on the symptoms of psychotic patients, however, has produced a somewhat different picture. Using

factor analysis, Liddle11 first reported 3 clusters of positive, negative, and cognitive disorganization symptoms,

but more recent research has converged on 5 factors by

adding depression and mania as separate factors.12,13

To add further levels of complexity, some studies have

suggested that, superordinate to both the internalizingexternalizing-psychosis spectra14 and the 5-factor model

of psychosis,15 there is a general psychopathology or

P factor common to all psychiatric disorders, perhaps

reflecting neuroticism or emotional instability (this latter

type of model is known as a bifactor model).

It is not yet clear if or how these models can be reconciled. As depression seems to belong to anxious misery in the internalizing spectrum and mania presumably

belongs to the externalizing spectrum, it is tempting to

nest the remaining psychosis factors within the psychosis

spectrum (see figure1) leading to a hierarchical classification scheme similar to the system used by biologists when

classifying species (note that this scheme can, in principle,

be continued further, eg, by dividing hallucinations into

different subtypes; see McCarthy-Jones etal16). However,

such a scheme would have to overcome many obstacles.

It should be recognized, to begin with, that it is a classification of symptoms and not people (a distinction which

is sometimes overlooked). Indeed, patients can obviously

experience more than one type of symptom, whichever

level we decide to describe them on. There is as yet no

evidence that either the Internalizing-ExternalizingPsychosis, 5 factor or hybrid models efficiently predict,

eg, responses to particular treatments or map on to etiological factors such as genetic or neuropsychological

variables. It is no wonder that many researchers believe

that, pragmatically, we have no alternative but to cling to

categorical diagnoses for the time being.

Clearly, psychiatric taxonomy is a work in progress,

and the comparison with biological species may be

R. P.Bentall

Shortcutting the Quest for Elusive Structure

Research targeted at particular symptoms such as hallucinations has long been recognized as a rational strategy

for bypassing the unsolved problem of psychiatric classification,25 as exemplified by the contributions to this

special supplement, none of which focus specifically on

schizophrenia. Borsbooms19 network analysis provides

further impetus for this approach, because the attempt

to understand the mechanisms underlying each symptom

will help us understand the networks of causal relationships between them. For example, to understand that

delusions can sometimes lead to hallucinations it helps

to know that the perceptual judgments of hallucinating

patients are excessively influenced by their prior beliefs.

Further advantages of a symptom-based research strategy have been noted by others, eg, the likelihood of

revealing mechanisms that are suitable targets for pharmacological4 or psychological26 intervention.

However, the comorbidity between symptoms observed

in taxonomic research and explained by the network

model also raises the hazard that factors attributed to one

symptom will be misattributed to a comorbid symptom.

Avoiding this hazard requires the use of careful designs

and appropriate statistical techniques. For example, a

wide range of social adversities are known to increase the

risk of psychosis, including childhood trauma and the

loss of a parent at an early age but, only by controlling

for the comorbidity between symptoms is it possible to

show that childhood sexual abuse is a more potent risk

factor for hallucinations than paranoid delusions and

that, conversely, attachment-threatening events are a

S200

greater risk factor for paranoia than hallucinations.27,28

Similarly, although abnormal metacognitive beliefs have

sometimes been thought to play a causal role in hallucinations,29 when controlling for comorbid symptoms,

it seems that metacognitive beliefs are implicated in the

distress associated with hallucinations rather than their

occurrence.30

As the contributors to this special supplement demonstrate, further progress in symptom-based research will

require multiple methodologies and perspectives, ranging from the humanities,31 through psychology (many of

the contributions) to the neurosciences.32 Attention must

be given to phenomenology (as demonstrated by most

of the other contributions). For some purposes it will

be important to study subtypes,16 particular modalities

(visual hallucinations having been relatively neglected;

Waters et al33) or dimensions of experience.34 Research

must not only focus on patients but also healthy individuals35 and should consider special groups such as children36

or people living in non-Western cultures.37 Undoubtedly,

symptom-based research has the potential to enhance

our ability to help people who are distressed by their psychotic experiences, either through novel interventions26 or

by aligning itself with service user and expert-by-experience initiatives.38

Symptom-based research is compatible with the NIMH

RDoC approach5 because the strategy concerns the

objects of research whereas RDoC concerns the mechanisms to be investigated. I have argued elsewhere that it

has the potential to lead to an entirely satisfactory account

of psychopathology20 but, in the spirit of promiscuous

realism, perhaps Ishould now say that it might have this

potential. Whether, after a second century of research on

psychosis, we will still need the kind of categorical diagnoses that have been used so often during the first century

seems doubtful, but will only become evident with time.

Acknowledgment

The author has declared that there are no conflicts of

interest in relation to the subject of this study.

References

1. Brockington I. Schizophrenia: yesterdays concept. Eur

Psychiatry. 1992;7:203207.

2. Bentall RP. The syndromes and symptoms of psychosis: or

why you cant play 20 questions with the concept of schizophrenia and hope to win. In: Bentall RP, ed. Reconstructing

Schizophrenia. London: Routledge; 1990:2360.

3. Craddock N, Owen MJ. The beginning of the end for the

Kraepelinian dichotomy. Br J Psychiatry. 2005;186:364366.

4. Fibiger HC. Psychiatry, the pharmaceutical industry, and the

road to better therapeutics. Schizophr Bull. 2012;38:649650.

5. Ford JM, Morris SE, Hoffman RE, et al. Studying hallucinations within the NIMH RDoC framework. Schizophr Bull.

2014.

Downloaded from http://schizophreniabulletin.oxfordjournals.org/ at UTALCA on August 5, 2014

because problems of concentration are often regarded as

symptoms of both. Syndromes and comorbidity between

diagnoses therefore emerge as a consequence of networks

of causal relations between symptoms.

In an analysis of the positive syndrome which anticipated Borsbooms work, Ipreviously noted that hallucinations might sometimes give rise to delusions and vice

versa.20 For example, it has long been recognized that

delusional beliefs can be prompted by attempts to explain

anomalous experiences21 and one well-known psychological model of paranoia gives priority to this mechanism.22 It is less recognized that the perceptual judgments

of hallucinating patients can be influenced by suggestions

affecting their beliefs about what they are likely to experience.23 Consistent with this network account, a recent

study investigated whether hallucinations precede delusions or vice versa in first episode psychosis, and found

that 18.2% of patients experienced delusions only, in

19.5% of cases delusions preceded hallucinations by at

least 1 month, and in 16.4% hallucinations preceded delusions.24 In the remaining 45.9% both symptoms appeared

within the same month (interestingly, no patients who

experienced hallucinations alone were recorded).

The Search for Elusive Structure

24. Compton MT, Potts AA, Wan CR, Ionescu DF. Which came

first, delusions or hallucinations? An exploration of clinical

differences among patients with first-episode psychosis based

on patterns of emergence of positive symptoms. Psychiatry

Res. 2012;200:702707.

25. Bentall RP, Jackson HF, Pilgrim D. Abandoning the concept

of schizophrenia: some implications of validity arguments

for psychological research into psychotic phenomena. Br J

Clin Psychol. 1988;27(pt 4):303324.

26. Thomas N, Hayward M, Peters E, et al. Psychological therapies for auditory hallucinations (voices): current status and

key directions for future research. Schizophr Bull. 2014.

27. Bentall RP, Wickham S, Shevlin M, Varese F. Do specific

early-life adversities lead to specific symptoms of psychosis? Astudy from the 2007 the Adult Psychiatric Morbidity

Survey. Schizophr Bull. 2012;38:734740.

28. Sitko K, Bentall RP, Shevlin M, OSullivan N, Sellwood, W.

Associations between specific psychotic symptoms and specific childhood adversities are mediated by attachment styles.

Psychiatry Res. In press.

29. Morrison AP. The interpretation of intrusions in psychosis:

an integrative cognitive approach to hallucinations and delusions. Behav Cogn Psychother. 2001;29:257276.

30. Varese F, Bentall RP. The metacognitive beliefs account of

hallucinatory experiences: a literature review and meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2011;31:850864.

31. Woods A, Jones N, Bernini M, et al. Interdisciplinary

approaches to the phenomenology of auditory verbal hallucinations. Schizophr Bull. 2014.

32. Ffytche DH, Wible CG. From tones in tinnitus to sensed

social interaction in schizophrenia: how understanding cortical organization can inform the study of hallucinations and

psychosis. Schizophr Bull. 2014.

33. Waters F, Collerton D, Ffytche D, et al. Information from

neurodegenerative disorders and eye disease. Schizophr Bull.

2014.

34. Woodward TS, Jung K, Hwang H, et al. Symptom dimensions of the psychotic symptom rating scales (PSYRATS) in

psychosis: a multi-site study. Schizophr Bull. 2014.

35. Johns L, Kompus K, Connell M, et al. Auditory verbal hallucinations in persons with and without a need for care.

Schizophr Bull. 2014.

36. Jardri R, Bartels-Velthuis AA, Debban M, et al. From phenomenology to neurophysiological understanding of hallucinations in children and adolescents. Schizophr Bull. 2014.

37. Lari F, Luhrmann T, Bell V, et al. Culture and hallucinations: overview and future directions. Schizophr Bull. 2014.

38. Corstens D, Longden E, McCarthy-Jones S, Waddingham R,

Thomas N. Emerging perspectives from the Hearing Voices

Movement: implications for research and practice. Schizophr

Bull. 2014.

S201

Downloaded from http://schizophreniabulletin.oxfordjournals.org/ at UTALCA on August 5, 2014

6. Bentall RP. Doctoring the Mind: Why Psychiatric Treatments

Fail. London: Penguin; 2009.

7. Freedman R, Lewis DA, Michels R, etal. The initial field trials of DSM-5: new blooms and old thorns. Am J Psychiatry.

2013;170:15.

8. Krueger RF. The structure of common mental disorders.

Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56:921926.

9. Kessler RC, Ormel J, Petukhova M, et al. Development

of lifetime comorbidity in the World Health Organization

world mental health surveys. Arch Gen Psychiatry.

2011;68:90100.

10. Kotov R, Chang SW, Fochtmann LJ, etal. Schizophrenia in

the internalizing-externalizing framework: a third dimension?

Schizophr Bull. 2011;37:11681178.

11. Liddle PF. The symptoms of chronic schizophrenia. A reexamination of the positive-negative dichotomy. Br J

Psychiatry. 1987;151:145151.

12. Demjaha A, Morgan K, Morgan C, et al. Combining

dimensional and categorical representation of psychosis:

the way forward for DSM-V and ICD-11? Psychol Med.

2009;39:19431955.

13. van Os J, Kapur S. Schizophrenia. Lancet. 2009;374:635645.

14. Caspi A, Houts RM, Belsky DW, etal. The p factor: one general psychopathology factor in the structure of psychiatric

diorders? Clin Psychol Sci. 2014;2:119137.

15. Reininghaus U, Priebe S, Bentall RP. Testing the psychopathology of psychosis: evidence for a general psychosis dimension. Schizophr Bull. 2013;39:884895.

16. McCarthy-Jones S, Thomas N, Strauss C, et al. Better than

mermaids and stray dogs? Subtyping auditory verbal hallucinations and its implications for research and practice.

Schizophr Bull. 2014.

17. Dupr J. The Disorder of Things: Metaphysical Foundations of

the Disunity of Science. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University

Press; 1993.

18. Borsboom D. Psychometric perspectives on diagnostic systems. J Clin Psychol. 2008;64:10891108.

19. Borsboom D, Cramer AO. Network analysis: an integrative

approach to the structure of psychopathology. Annu Rev Clin

Psychol. 2013;9:91121.

20. Bentall RP. Madness Explained: Psychosis and Human

Nature. London: Penguin; 2003.

21. Maher BA. Delusional thinking and perceptual disorder.

J Individ Psychol. 1974;30:98113.

22. Freeman D, Garety PA, Kuipers E, Fowler D, Bebbington

PE. A cognitive model of persecutory delusions. Br J Clin

Psychol. 2002;41:331347.

23. Haddock G, Slade PD, Bentall RP. Auditory hallucinations

and the verbal transformation effect: the role of suggestions.

Pers Indiv Differ. 1995;19:301306.

You might also like

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- English II Homework Module 6Document5 pagesEnglish II Homework Module 6Yojana DubonNo ratings yet

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- 2 How To - Tests of Copy Configuration From Client 000 - Note 2838358 - Part3Document15 pages2 How To - Tests of Copy Configuration From Client 000 - Note 2838358 - Part3Helbert GarofoloNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Innoventure List of Short Listed CandidatesDocument69 pagesInnoventure List of Short Listed CandidatesgovindmalhotraNo ratings yet

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Chemical EngineeringDocument26 pagesChemical EngineeringAnkit TripathiNo ratings yet

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- CLOCKSDocument62 pagesCLOCKSdasarajubhavani05No ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Sasi EnriquezDocument9 pagesSasi EnriquezEman NolascoNo ratings yet

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Expanding UNIT 1 For 2º ESO.-the History of Music NotationDocument1 pageExpanding UNIT 1 For 2º ESO.-the History of Music NotationEwerton CândidoNo ratings yet

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Solar Water Pump Supreme RevDocument22 pagesSolar Water Pump Supreme RevBelayneh TadesseNo ratings yet

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Gate Question (Limit) PDFDocument4 pagesGate Question (Limit) PDFArpit Patel75% (4)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Director Engineering in Detroit MI Resume Shashank KarnikDocument3 pagesDirector Engineering in Detroit MI Resume Shashank Karnikshashankkarnik100% (1)

- D062/D063/D065/D066 Service Manual: (Book 1 of 2) 004778MIU MainframeDocument1,347 pagesD062/D063/D065/D066 Service Manual: (Book 1 of 2) 004778MIU MainframeevpsasaNo ratings yet

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- MODBUSDocument19 pagesMODBUSJosé Luis MartínezNo ratings yet

- About Karmic Debt Numbers in NumerologyDocument3 pagesAbout Karmic Debt Numbers in NumerologyMarkMadMunki100% (2)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Unit 3Document9 pagesUnit 3Estefani ZambranoNo ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Green ManagementDocument58 pagesGreen ManagementRavish ChaudhryNo ratings yet

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Backup Archive and Recovery Archive Users and PermissionsDocument5 pagesBackup Archive and Recovery Archive Users and PermissionsgabilovesadellaNo ratings yet

- Modicon M580 Quick Start - v1.0 - Training ManualDocument169 pagesModicon M580 Quick Start - v1.0 - Training Manualaryan_iust0% (1)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Leadership and FollowershipDocument43 pagesLeadership and FollowershipNishant AgarwalNo ratings yet

- Testing: Instructor: Iqra JavedDocument32 pagesTesting: Instructor: Iqra Javedzagi techNo ratings yet

- Effective Problem Solving and Decision MakingDocument46 pagesEffective Problem Solving and Decision MakingAndreeaMare1984100% (2)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- F PortfolioDocument63 pagesF PortfolioMartin SchmitzNo ratings yet

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Daily Lesson Log: Department of EducationDocument10 pagesDaily Lesson Log: Department of EducationStevenson Libranda BarrettoNo ratings yet

- Absolute Duo 1 PDFDocument219 pagesAbsolute Duo 1 PDFAgnieškaRužičkaNo ratings yet

- Lab ManualDocument69 pagesLab ManualPradeepNo ratings yet

- Titanic Is A 1997 American Romantic Disaster Film Directed, Written. CoDocument13 pagesTitanic Is A 1997 American Romantic Disaster Film Directed, Written. CoJeric YutilaNo ratings yet

- A Brief About Chandrayaan 1Document3 pagesA Brief About Chandrayaan 1DebasisBarikNo ratings yet

- Fall 2011 COP 3223 (C Programming) Syllabus: Will Provide The Specifics To His SectionDocument5 pagesFall 2011 COP 3223 (C Programming) Syllabus: Will Provide The Specifics To His SectionSarah WilliamsNo ratings yet

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Carl Jung - CW 18 Symbolic Life AbstractsDocument50 pagesCarl Jung - CW 18 Symbolic Life AbstractsReni DimitrovaNo ratings yet

- DonnetDocument12 pagesDonnetAsia SzmyłaNo ratings yet

- Lip Prints: IntroductionDocument4 pagesLip Prints: Introductionkaran desaiNo ratings yet

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)