Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Book Review - Encyclopedia of Canonical Hadith

Uploaded by

Ihsān Ibn SharīfCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Book Review - Encyclopedia of Canonical Hadith

Uploaded by

Ihsān Ibn SharīfCopyright:

Available Formats

Islamic Law

and

Society

Islamic Law and Society 15 (2008) 408-423

www.brill.nl/ils

Book Reviews

Encyclopedia of Canonical adth. By G.H.A. Juynboll. Leiden/Boston: Brill, 2007.

Pp. xxxiii + 804. ISBN 978 90 04 15674 6. 209; $289.00.

This hefty volume comprises first an introduction presenting the latest version of

Juynbolls method of adth criticism, second a long, alphabetical list of persons

with whom canonical traditions may be associated, then a list of 45 traditionists

also identified as abdl, an index to the alphabetical list, and finally an index of

Qurnic passages cited. Juynboll expounded his basic method, with appropriate

credit to Joseph Schacht, in Muslim Tradition (Cambridge University Press, 1983).

He collects and compares the asnd to any particular adth report and looks for

the Common Link, the earliest person in the complex who evidently dictated this

basic text to multiple auditors. In subsequent articles, he has introduced many

refinements, notably the Partial Common Link, a teacher with multiple auditors

besides the evident Common Linkthe more of these, the more plausible the

identification of the Common Link above them; the dive by which someone

reports having heard the same adth report through an otherwise unattested chain

from the Common Links own reported source; and the spider, a collection of

single strands, uncorroborated lines of transmission up to the putative source.

These are clearly and succinctly described in the introduction to the Encyclope

dia.

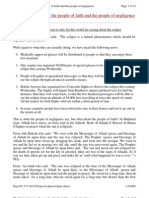

600

500

400

300

Hadith invented

200

100

0

10s

30s

50s

70s

90s 110s 130s 150s 170s 190s 210s 230s

Juynboll lists about 150 traditionists, to whom he assigns 2,280 adth reports,

with texts in translation (necessarily ignoring most variant wordings). Here is a

time line of the invention of adth, according to his estimates:

Juynboll credits Ibn Abbs with two adth reports, or at least holds that their

content is conceivably from the time of the Prophet; he credits ishah more

confidently with six. The great age of inventing adth, or more precisely mutn

as they appear in the Six Books (i.e., not counting the invention of alternative

Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, 2008

DOI: 10.1163/156851908X366174

Book Reviews / Islamic Law and Society 15 (2008) 408-423

409

asnd), appears to be the lifetime of alShfi and the half-century before, contra

Schacht, who asserted that it was his lifetime and the half-century after. The

champions are alZuhr with 86 to his credit, alAmash with 153, Sufyn b.

Uyayna with 175, Shuba with 316, and Mlik with 373. Juynboll expresses some

interesting preferences among later collectors; e.g., for Ibn Ab Shayba over Abd

alRazzq, Amad b. anbal, and other major collectors of the 3rd/9th century

and, among the Six Books, for Bukhr and Muslim over the other four where

they include a adth report that Bukhr and Muslim do not.

Let me review a sample entry, chosen at random: Mlik b. Mighwal (d. 157

or 159/774 or 776)regrettably, Juynbolls conversion from Hijri to Common

Era is usually approximate, without split dates, and sometimes erroneouswas

an Arab who lived in Kufa. After a few comments on his reputation, Juynboll

quotes the one adth report that he will identify Mlik b. Mighwal as inventing:

ala b. Muarrif asks Abd Allh b. Ab Awf, Did the Prophet leave a will?

No, he said. But, ala went on, why are the Muslims enjoined to leave a

testament at all? Said Abd Allh, He charged us to follow the Book of God.

After quoting this matn, Juynboll follows it with a series of citations, beginning

with the number of this adth report in alMizz, Tufa. Juynboll then notes,

Mlik b. Mighwal has three PCLs and several SSs in this bundle which supports

one version of a MC, so he is in any case the (S)CL (see pp. 404-05). Abbreviated,

here are some common terms of Juynbolls: Partial Common Link, Single Strand,

Matn Cluster, and Seeming Common Link. The persistence of parentheses around

seeming is an example of the provisional, speculative nature of Juynbolls evalua

tions, often expressly acknowledged. Furthermore, t[irmidh] is quoted that

Mlik b. Mighwal tafarrada bihi, which amounts to saying that he is probably

the CL of this tradition . What substantiates Mlik b. Mighwals position in

this bundle as (S)CL is the fact that in ilya, V, p. 21, lines 14-18, a number

of people are enumerated that emphasize his key figure position even more

convincingly. Juynboll is fairly disparaging of the Islamic tradition of adth

criticism, asserting, for example, that although noticing the phenomenon of

Common Links, pre-modern critics fail to draw plausible conclusions (xxiii).

Sometimes, I think he is overly harsh, as when he alleges that absence of a year

of death is mostly a sure sign that a certain figure is a majhl (p. 417). Sixty

percent of the transmitters in the Six Books have no dates at all attached to them.

Mostly minor figures, perhaps they are so many unknowns. But even major figures

are often associated with multiple proposed death dates, like the figure Juynboll

has just called a majhl; e.g., alAwz and Sufyn alThawr. I would say that

uncertainty about a transmitters death dates is due to biographers inferring data

from the asnd in which he appeared, which showed them who had been able

to meet and relate adth from him. Accordingly, I doubt whether the biographical

record is an independent source when it says that someone met someone else, but

I also doubt whether uncertainty about death dates must have come from the

invention of names in asnd. Nevertheless, as the entry on Mlik b. Mighwal

illustrates, Juynbolls actual method depends heavily on pre-modern scholarship

410

Book Reviews / Islamic Law and Society 15 (2008) 408-423

the Encyclopedia is generously dedicated to Abd a-amad Sharaf ad-Dn, first

editor of the Tufaand seems rather more complementary to it than Harald

Motzkis method.

Students of early Islamic law will probably wish to consult Juynboll on all the

adth reports they consider, giving his assessments more or less weight as they

consider his method more or less reliable. For an article I recently completed about

judicial procedure, especially the principle that proof is incumbent on the plaintiff,

an oath on the defendant, succinctly stated in a famous adth report, I wished

that Juynbolls index were more detailed. I find no entry for defendant, plaintiff,

or law suit. Under oath, there are 26 page references without further analysis.

After working through them, I did find the one I wanted, which happened to be

the thirteenth. Juynboll attributes the adth reports preface (about the need to

restrain human cupidity) and second half (about the defendant) to Ibn Jurayj (p.

220). But, because he omits to consider most literature apart from the Six Books,

he does not mention advocacy of the principle by the anafi school (where the

earliest sources attribute the saying to Followers, not to the Prophet), to which I

would characterize Ibn Jurayjs adth report as a response.

Another test: in an article about women in mosques, I began with a treatment of the adth report, Forbid not Gods handmaidens to enter the mosque

(Whether to Keep Women out of the Mosque: A Survey of Medieval Islamic

Law, Proceedings of the 22nd Congress of LUnion Europenne des Arabisants et

Islamisants). Fortunately, in Juynbolls index, women is not one entry. Rather,

the index has one reference for women in the mosque, which led me to Sufyn

b. Uyayna (d. 198/814), whom Juynboll credits with the version, When a mans

wife asks to go to the mosque, he should not stop her. Another entry, women

forbidden to go to mosque, led me to this, which Juynboll ascribes to the Kufan

alAmash (d. 148/765-6?): Ibn Umar related the Prophets words: Do not prevent

your women from going out in the night to the mosque. Then a son of Ibn

Umars said: We will not let them go out to defile the place. Whereupon Ibn

Umar scolded him and said: I said that the Messenger of God said this, and you

say: We wont let them?! I have supposed that the controversy was older than

alAmash, but this particular wording need not be older. Forbid not Gods

handmaidens to enter the mosque is not in the Encyclopedia because, evidently,

it is supported only by single strands, about which Juynboll will draw no conclu

sions. I observed that these permissive adth reports were Medinese in their upper

reaches (Companion and Follower levels), whereas Kufan sources reported negative

positions of Ibn Masd and Ibrhm alNakha, from which I inferred that Kufa

was the home of opposition to womens going to the mosque, opposition that

survived in the relatively restrictive position of the anafi school. Juynbolls analysis

would suggest nothing of the sort, although harmonization is possible: if alAmash

was indeed the author of this form of the report, then he gives us a dissident

Kufan view, also a clear terminus ante quem for the principle that the Prophets

dicta have priority over Followers. What I conclude is first that one dare not end

Book Reviews / Islamic Law and Society 15 (2008) 408-423

411

an investigation of some early legal controversy at Juynbolls verdict, but second

that one may expect such an investigation to be enriched by consulting Juyn

boll.

I think this is enough to justify adding the Encyclopedia to ones library. The

introduction becomes the first place to send a student for an exposition of Juynbolls

method, as I think I would send the same student first to Harald Motzki, Dating

Muslim Traditions, Arabica, lii (2005), 204-53, for an exposition of his method

and to Eerik Dickinson, The Development of Early Sunnite adth Criticism (Leiden:

Brill, 2001), chapter 6, for an exposition of 9th and 10th-century Sunni methods

(as distinct from the list of technical terms that has usually served for a description

of pre-modern adth criticism, I suspect by incautious reliance on the literature

of ul alfiqh).

Christopher Melchert

University of Oxford

You might also like

- A Review of JuynbollDocument10 pagesA Review of JuynbollOlfa BaghniNo ratings yet

- The Imamis Between Rationalism and TraditionalismDocument12 pagesThe Imamis Between Rationalism and Traditionalismmontazerm100% (1)

- Reading Between The Lines The Compilation of Hadith and The Authoral VoiceDocument31 pagesReading Between The Lines The Compilation of Hadith and The Authoral VoiceMuhammad NizarNo ratings yet

- Some Reflections On Alleged Twelver Shia Attitudes Towards The Integrity of The Qur'AnDocument18 pagesSome Reflections On Alleged Twelver Shia Attitudes Towards The Integrity of The Qur'AnAfzal SumarNo ratings yet

- Early Shiite Hermeneutics and The Dating of KitābDocument22 pagesEarly Shiite Hermeneutics and The Dating of KitābkomailrajaniNo ratings yet

- Taqrib - A Study of Attempts at Sunni-shi'Ia Rapprochement in HistoryDocument19 pagesTaqrib - A Study of Attempts at Sunni-shi'Ia Rapprochement in HistoryIbrahima SakhoNo ratings yet

- The Virtuous Son of The Rational, A Traditionalist's Response To The Falasifah - Nahyan FancyDocument38 pagesThe Virtuous Son of The Rational, A Traditionalist's Response To The Falasifah - Nahyan FancyfalahNo ratings yet

- Orgin of WahabismDocument51 pagesOrgin of WahabismM. Najam us Saqib Qadri al HanbliNo ratings yet

- TahrifDocument15 pagesTahrifsherazed77No ratings yet

- Ahmet T Karamustafa - Rethinking Ibn ArabiDocument3 pagesAhmet T Karamustafa - Rethinking Ibn ArabiHabral El-AttasNo ratings yet

- Ibn Tymiyyah Sufi SheikhDocument15 pagesIbn Tymiyyah Sufi SheikhD BNo ratings yet

- Mutazilism in The Age of AverroesDocument33 pagesMutazilism in The Age of AverroesTsanarNo ratings yet

- A Book Review On On Taqlid Ibn Al QayyimDocument3 pagesA Book Review On On Taqlid Ibn Al QayyimTaymiNo ratings yet

- Dickinson Eerik - The Development of Early Sunnite Hadith Criticism The Taqdima of Ibn Abi Hatim Al-Razi - Xbook XhadithDocument157 pagesDickinson Eerik - The Development of Early Sunnite Hadith Criticism The Taqdima of Ibn Abi Hatim Al-Razi - Xbook Xhadithshurahbi100% (2)

- Analyzing A Tool of Is Propaganda Ibn ADocument16 pagesAnalyzing A Tool of Is Propaganda Ibn Abidor43362No ratings yet

- Ibn Al Qayyim - AssignmentDocument5 pagesIbn Al Qayyim - AssignmentAzmyNo ratings yet

- Philosophical ExcegesisDocument13 pagesPhilosophical ExcegesisKhandkar Sahil RidwanNo ratings yet

- A Pre-Modern Defense of Hadiths Against PDFDocument53 pagesA Pre-Modern Defense of Hadiths Against PDFMansur AliNo ratings yet

- Jewish and Christian Reception S of Muslim Teology PDFDocument12 pagesJewish and Christian Reception S of Muslim Teology PDFdibekhNo ratings yet

- Wahdat Al-Wujud As Post-Avicennian ThoughtDocument21 pagesWahdat Al-Wujud As Post-Avicennian Thoughtas-Suhrawardi100% (1)

- Cambridge University Press School of Oriental and African StudiesDocument4 pagesCambridge University Press School of Oriental and African StudiesAxx A AlNo ratings yet

- A Refutation of J Van Enn About His Allegation On Imam HamnbalDocument19 pagesA Refutation of J Van Enn About His Allegation On Imam HamnbalHANBAL CONTRA MUNDUMNo ratings yet

- From Al-Ghazali To Al-Razi: 6th/ 12th Century Developments in Muslim Philosophical TheologyDocument39 pagesFrom Al-Ghazali To Al-Razi: 6th/ 12th Century Developments in Muslim Philosophical Theologyalif fikri100% (1)

- Andalusi Mysticism, A RecontextualizationDocument34 pagesAndalusi Mysticism, A Recontextualizationvas25100% (1)

- Abdullah Bin Hamid AliDocument9 pagesAbdullah Bin Hamid AliAjša Sabina KurtagićNo ratings yet

- The Jewish Christians of The Early Centuries of Christianity According To A New SourceDocument16 pagesThe Jewish Christians of The Early Centuries of Christianity According To A New SourceJoaquín RieraNo ratings yet

- A Religious Transformation in Late AntiquityDocument41 pagesA Religious Transformation in Late AntiquityRaoul VillanoNo ratings yet

- IHIW 2 - Thiele 1Document20 pagesIHIW 2 - Thiele 1Alper TercanNo ratings yet

- Abraham, Hagar and Ishmael at Mecca: A Contribution to the Problem of Dating Muslim TraditionsDocument27 pagesAbraham, Hagar and Ishmael at Mecca: A Contribution to the Problem of Dating Muslim TraditionsDrawUrSoulNo ratings yet

- Mawlid Al-Nabi JustificationDocument11 pagesMawlid Al-Nabi JustificationIbrahim QuadriNo ratings yet

- Schwarb Off PrintDocument32 pagesSchwarb Off PrintFrancesca GorgoniNo ratings yet

- Abuzayd On Ibn Arabi PDFDocument16 pagesAbuzayd On Ibn Arabi PDFKarl MerserNo ratings yet

- The Jewish Christians of the Early Centuries of Christianity according to a New Source- היהודים-הנוצרים במאות הראשונות של הנצרות על פי מקור חדשDocument75 pagesThe Jewish Christians of the Early Centuries of Christianity according to a New Source- היהודים-הנוצרים במאות הראשונות של הנצרות על פי מקור חדשאליהו אלמני טוסיה100% (1)

- 623-Article Text-1550-1-10-20180419 AL-ASH' ARI AND HIS CONCEPT OF of TawhidDocument11 pages623-Article Text-1550-1-10-20180419 AL-ASH' ARI AND HIS CONCEPT OF of TawhidSimeonNo ratings yet

- Muqātil B. Sulaymān and Anthropomorphism: Encyclopaedia of Islam, M. Plessner Describes Quite ConfidentlyDocument32 pagesMuqātil B. Sulaymān and Anthropomorphism: Encyclopaedia of Islam, M. Plessner Describes Quite ConfidentlyEzaz UllahNo ratings yet

- 2010 Reinhart JuynbollianaDocument33 pages2010 Reinhart JuynbollianaphotopemNo ratings yet

- Ibn Mujahid and Seven Established Reading of The Quran PDFDocument19 pagesIbn Mujahid and Seven Established Reading of The Quran PDFMoNo ratings yet

- A Post-Ghazalian Critic of Avicenna - Ibn Ghaylan Al-Balkhi On The Canon of MedicineDocument40 pagesA Post-Ghazalian Critic of Avicenna - Ibn Ghaylan Al-Balkhi On The Canon of MedicineIhsān Ibn SharīfNo ratings yet

- 2010 Reinhart Juynbolliana PDFDocument33 pages2010 Reinhart Juynbolliana PDFamnoman17No ratings yet

- Was Al-Shafii The Master Architect of Islamic Jurisprudence - Wael HallaqDocument20 pagesWas Al-Shafii The Master Architect of Islamic Jurisprudence - Wael HallaqBehram Khan100% (1)

- Brill Arabica: This Content Downloaded From 130.15.241.167 On Sun, 05 Jun 2016 09:00:07 UTCDocument21 pagesBrill Arabica: This Content Downloaded From 130.15.241.167 On Sun, 05 Jun 2016 09:00:07 UTCMuhammad Wasim ArifNo ratings yet

- The Hanbali School and Sufism - Dr. George MakdisiDocument12 pagesThe Hanbali School and Sufism - Dr. George Makdisisyed quadriNo ratings yet

- Ta Awwuf and Reform in Pre Modern Islamic Culture in Search of Ibrāhīm Al KūrāniDocument50 pagesTa Awwuf and Reform in Pre Modern Islamic Culture in Search of Ibrāhīm Al KūrāniMaryumiNo ratings yet

- Insights on Sefer ha-Ot Critical EditionDocument34 pagesInsights on Sefer ha-Ot Critical EditionMatveev PlayBoy100% (1)

- 10th Century Syriac GospelDocument93 pages10th Century Syriac GospelYeshua Abdul Mu'min100% (1)

- Book Review: A Journey Through Torah: A Critique of The Documentary HypothesisDocument2 pagesBook Review: A Journey Through Torah: A Critique of The Documentary HypothesisFPSMNo ratings yet

- Ibn Al-Qayyim'S Kitab Al-Ruh: Some Literary Aspects.: ResearchgateDocument21 pagesIbn Al-Qayyim'S Kitab Al-Ruh: Some Literary Aspects.: ResearchgateSHAIK KHAJA PEERNo ratings yet

- Review of Scholarship on Early Islamic Law and JurisprudenceDocument6 pagesReview of Scholarship on Early Islamic Law and JurisprudenceMuhammad FahmiNo ratings yet

- Imam Al-Bukhari's ContributionDocument8 pagesImam Al-Bukhari's ContributionIdriss Smith0% (1)

- Whelan - Forgotten WitnessDocument15 pagesWhelan - Forgotten WitnessOmar MohammedNo ratings yet

- Irrefutable Proof That Hanbalis Were SufisDocument10 pagesIrrefutable Proof That Hanbalis Were SufischefyousefNo ratings yet

- How Hanafism Originated in Kufa and Traditionalism in MedinaDocument30 pagesHow Hanafism Originated in Kufa and Traditionalism in Medinaask1984No ratings yet

- The Identity of The Sabians Some InsightsDocument22 pagesThe Identity of The Sabians Some InsightsAmmaar M. Hussein100% (1)

- Before Ūfiyyāt: Female Muslim Renunciants in The 8th and 9th Centuries CEDocument25 pagesBefore Ūfiyyāt: Female Muslim Renunciants in The 8th and 9th Centuries CESo' FineNo ratings yet

- Setting The Record StraightDocument26 pagesSetting The Record StraightkahoeNo ratings yet

- IK On SufismDocument30 pagesIK On SufismMohamed SoffarNo ratings yet

- Review of Julie Chajes and Boaz Huss Eds PDFDocument2 pagesReview of Julie Chajes and Boaz Huss Eds PDFtarek elagamyNo ratings yet

- Zaynab's Life and Role After the Battle of KarbalaDocument5 pagesZaynab's Life and Role After the Battle of KarbalaBahman BehNo ratings yet

- Faith and Reason in Islam: Averroes' Exposition of Religious ArgumentsFrom EverandFaith and Reason in Islam: Averroes' Exposition of Religious ArgumentsRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (3)

- Islamic Symbol ListDocument33 pagesIslamic Symbol ListIhsān Ibn SharīfNo ratings yet

- Bio IbnAshirDocument4 pagesBio IbnAshirAli NuriyevNo ratings yet

- Turn The CheekDocument9 pagesTurn The CheekIhsān Ibn SharīfNo ratings yet

- Book Review - Islamic Law and The State - The Constitutional Jurisprudence of Al-QarafiDocument4 pagesBook Review - Islamic Law and The State - The Constitutional Jurisprudence of Al-QarafiIhsān Ibn SharīfNo ratings yet

- RevisionDocument1 pageRevisionIhsān Ibn SharīfNo ratings yet

- JummaDocument2 pagesJummaIhsān Ibn SharīfNo ratings yet

- Book Review - Islamic Law - Theory and PracticeDocument2 pagesBook Review - Islamic Law - Theory and PracticeIhsān Ibn SharīfNo ratings yet

- Book Review - Early Islamic Legal Theory - The Risala of Al-ShafiiDocument4 pagesBook Review - Early Islamic Legal Theory - The Risala of Al-ShafiiIhsān Ibn SharīfNo ratings yet

- Book Review - Al-Ghazali Faith in Divine Unity and Trust in Divine ProvidenceDocument3 pagesBook Review - Al-Ghazali Faith in Divine Unity and Trust in Divine ProvidenceIhsān Ibn Sharīf0% (1)

- Poetics of Islamic HistoriographyDocument3 pagesPoetics of Islamic HistoriographyIhsān Ibn SharīfNo ratings yet

- Book Review - Early Maliki Law - Ibn Abd Al-Hakam and His Major Compendium of JurisprudenceDocument8 pagesBook Review - Early Maliki Law - Ibn Abd Al-Hakam and His Major Compendium of JurisprudenceIhsān Ibn SharīfNo ratings yet

- Book Review - A History of An Islamic School of Law - The Early Spread of Hanafism PDFDocument5 pagesBook Review - A History of An Islamic School of Law - The Early Spread of Hanafism PDFIhsān Ibn Sharīf100% (1)

- Book Review - Analysing Muslim Traditions in Legal Exegetical and Maghazi HadithDocument4 pagesBook Review - Analysing Muslim Traditions in Legal Exegetical and Maghazi HadithIhsān Ibn SharīfNo ratings yet

- Book Review - Applying The Canon of Islam - The Authorization and Maintenance of Interpretative Reasoning in Hanafi ScholarshipDocument2 pagesBook Review - Applying The Canon of Islam - The Authorization and Maintenance of Interpretative Reasoning in Hanafi ScholarshipIhsān Ibn SharīfNo ratings yet

- Book Review - A Study of Six Works of Medieval Islamic Jurisprudence PDFDocument2 pagesBook Review - A Study of Six Works of Medieval Islamic Jurisprudence PDFIhsān Ibn SharīfNo ratings yet

- Al-Ghazalis Use of Original Human Disposition and Its Background in The Teachings of Al-Farabi and AvicennaDocument32 pagesAl-Ghazalis Use of Original Human Disposition and Its Background in The Teachings of Al-Farabi and AvicennaIhsān Ibn SharīfNo ratings yet

- Book Review - A Guide To Conclusive Proofs For The Principles of BeliefDocument3 pagesBook Review - A Guide To Conclusive Proofs For The Principles of BeliefIhsān Ibn Sharīf0% (1)

- A Post-Ghazalian Critic of Avicenna - Ibn Ghaylan Al-Balkhi On The Canon of MedicineDocument40 pagesA Post-Ghazalian Critic of Avicenna - Ibn Ghaylan Al-Balkhi On The Canon of MedicineIhsān Ibn SharīfNo ratings yet

- Usul - Shashi - Version - Some Translation in Red BlueDocument99 pagesUsul - Shashi - Version - Some Translation in Red Bluenosheen67% (3)

- A Turn in The Epistemology and Hermeneutics of 20th Century Usul Al-FiqhDocument50 pagesA Turn in The Epistemology and Hermeneutics of 20th Century Usul Al-FiqhIhsān Ibn SharīfNo ratings yet

- Al-Ghazalis Concept of Prophecy - The Introduction of Avicennan Psychology Into Asharite TheologyDocument44 pagesAl-Ghazalis Concept of Prophecy - The Introduction of Avicennan Psychology Into Asharite TheologyIhsān Ibn SharīfNo ratings yet

- 13a. Sifah Tus SalahDocument56 pages13a. Sifah Tus SalahshaziasaleemNo ratings yet

- Dars e Nizami Catalogue 2015Document7 pagesDars e Nizami Catalogue 2015Anonymous qK4bUmWjp8No ratings yet

- Halal Food Awareness Research GoldenDocument27 pagesHalal Food Awareness Research GoldenJerson Dela TorreNo ratings yet

- The Benefits of Studying Usool al-FiqhDocument52 pagesThe Benefits of Studying Usool al-FiqhabassalishahNo ratings yet

- Article 1 - Woman, Half The ManDocument12 pagesArticle 1 - Woman, Half The Mansayonee73No ratings yet

- Gender, Religion, and SpiritualityDocument91 pagesGender, Religion, and SpiritualityOxfam100% (3)

- SALAWATDocument4 pagesSALAWATmohaideen77No ratings yet

- Islamic Studies Chapter 6 NotesDocument8 pagesIslamic Studies Chapter 6 NotesMaryam Khan (MK)No ratings yet

- Ijma & Qiyas: Key Sources of Islamic JurisprudenceDocument33 pagesIjma & Qiyas: Key Sources of Islamic Jurisprudenceayushakhalid100% (2)

- Women's Rights & Gender Inequality in Egypt & TunisiaDocument22 pagesWomen's Rights & Gender Inequality in Egypt & TunisiathayaneNo ratings yet

- Understanding Fiqh of MuslimDocument5 pagesUnderstanding Fiqh of MuslimchoronzoneNo ratings yet

- ASAS-ASAS KONTRAK DALAM HUKUM SYARI’AHDocument15 pagesASAS-ASAS KONTRAK DALAM HUKUM SYARI’AHRajabagus HarapanEntertaimentNo ratings yet

- Lecture Notes Module 2 (Islamic Scholarly Tradition)Document7 pagesLecture Notes Module 2 (Islamic Scholarly Tradition)MUHAMMAD WAZIRNo ratings yet

- Islamiyat Topical QuestionsDocument12 pagesIslamiyat Topical QuestionsSibraWaseem100% (1)

- 2022LHC6756Document28 pages2022LHC6756WaqasSanaNo ratings yet

- Che Omar Che Soh V PPDocument3 pagesChe Omar Che Soh V PPNadia Ezzati نادية اززاتي67% (6)

- Wedding - Marriage & Its Rules and Issues by Shaykh Muhammad Al-UthaymeenDocument10 pagesWedding - Marriage & Its Rules and Issues by Shaykh Muhammad Al-UthaymeenNasrin Akther100% (2)

- (Cambridge South Asian Studies) Gregory C. Kozlowski - Muslim Endowments and Society in British India-Cambridge University Press (1985)Document223 pages(Cambridge South Asian Studies) Gregory C. Kozlowski - Muslim Endowments and Society in British India-Cambridge University Press (1985)Zoraiz Asim100% (1)

- Chapter 1.sources of Hindu Law: Shruti Smriti Digest and Commentaries Custom and UsagesDocument18 pagesChapter 1.sources of Hindu Law: Shruti Smriti Digest and Commentaries Custom and UsagesMayur KasbeNo ratings yet

- The Eclipse Between The People of Faith and The People of NegligenceDocument12 pagesThe Eclipse Between The People of Faith and The People of NegligenceabdounouNo ratings yet

- Rekapitulasi Absen Perkuliahan Daring HKI, Senin 26 Februari 2024Document9 pagesRekapitulasi Absen Perkuliahan Daring HKI, Senin 26 Februari 2024botakadudu04No ratings yet

- Excessive Dower ProjectDocument5 pagesExcessive Dower ProjectToma ChowdhuryNo ratings yet

- Sources of LAWDocument13 pagesSources of LAWLeslie S. AndresNo ratings yet

- STIKES Attendance and Score ListDocument18 pagesSTIKES Attendance and Score ListAulia AzofaNo ratings yet

- Does The Quran Allow Sex With Prepubescent Girls? No!Document5 pagesDoes The Quran Allow Sex With Prepubescent Girls? No!Yahya SnowNo ratings yet

- Actionable ClaimDocument8 pagesActionable ClaimAdv NesamudheenNo ratings yet

- FAMILY CODE 144. Llave Vs RepublicDocument2 pagesFAMILY CODE 144. Llave Vs RepublicAgatha Bernice MacalaladNo ratings yet

- Towards International Islamic Human RightsDocument157 pagesTowards International Islamic Human RightsrahmanrajiNo ratings yet

- Penggunaan Lokasi Palsu (Mock Location) Oleh Mitra Pengemudi Transportasi Online (Grab) Di Kota Bandungditinjau Dari Hukum Ekonomi SyariahDocument16 pagesPenggunaan Lokasi Palsu (Mock Location) Oleh Mitra Pengemudi Transportasi Online (Grab) Di Kota Bandungditinjau Dari Hukum Ekonomi SyariahCepi Abdul BasitNo ratings yet

- Arab-Malaysian Finance BHD V Taman Ihsan Jaya SDN BHD & Ors (Koperasi Seri Kota Bukit Cheraka BHD, Third Party)Document30 pagesArab-Malaysian Finance BHD V Taman Ihsan Jaya SDN BHD & Ors (Koperasi Seri Kota Bukit Cheraka BHD, Third Party)Hadhirah AzharNo ratings yet