Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Skeleton From Iran Cave

Uploaded by

Wesley MuhammadCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Skeleton From Iran Cave

Uploaded by

Wesley MuhammadCopyright:

Available Formats

The Human Skeletal Remains from Hotu Cave, Iran

Author(s): J. Lawrence Angel

Source: Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, Vol. 96, No. 3 (Jun. 20, 1952), pp.

258-269

Published by: American Philosophical Society

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3143835 .

Accessed: 06/12/2013 23:00

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

American Philosophical Society is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to

Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 67.115.155.19 on Fri, 6 Dec 2013 23:00:01 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE HUMAN SKELETAL REMAINS FROM HOTU CAVE, IRAN

J. LAWRENCE ANGEL

AssociateProfessor

ofAnatomyand PhysicalAnthropology,

Jefferson

MedicalCollege

(Read November8, 1951)

THREE

skeletons plus scraps of two other

skulls excavated by ProfessorCarleton S. Coon

of the UniversityMuseum last spring fromthe

4th glacial gravel layer about 30 feet below the

presentsurfaceof Hotu Cave are a big haul for

theirUpper Palaeolithicdate. But theyare not

a large enough sample for certaintythat they

resembledtheirhuntingcousinsin Upper PalaeolithicEurope (Morant, 1926, 1929; von Bonin,

1935: sample size about 40) more closely than

their possible descendantsin northernIran, the

farmingand copper-usingvillagersof 4th millennium B.C. Sialk and Hasan (Vallois, 1939, and

Morant, 1938: about 27 skulls available), whose

connectionswill be furtherclarifiedwhen study

of the Mesolithic (Coon, 1951) and Neolithic

skeletonsfromBelt Cave can be completed. But

the Hotu hunterswere certainlylarge-brained

and

of Homo sapiens.

fullydevelopedrepresentatives

They show no visibleNeanderthaltraits. Except

for stronglyworn teeth and certain functional

details of the skeletonthey could be duplicated

individuallytodayhereor in the Near East.

Reconstruction

of the remainsis stillin process,

withconsiderableworkstillto be done on theless

completecrania,numbers1 and 3. But withthe

ingenioushelp of Mr. AlbertJehle,of the UniversityMuseum,it has been possibleto complete

the skull of number2, to take endocranialand

externalcasts of it, and also to restorethe entire

pelvisand vertebralcolumn,hands,and longbones

of thissame person. The burialtogetherof numbers 2 and 3 complicatedthe whole process of

mendingtheskeletons. It is easy now to separate

thecompletebones of thesetwo skeletonsby their

in morphologyand in color or patinadifferences

tion. But the originalsortingout of small fragmentstookmorethanthreetimesthetimeneeded

for a single skeleton (each long bone fragment

had to be triedin fourpossiblelimbs,each axial

in two possibleplaces).

skeletonfragment

Dr. Coon has honoredme deeplyby givingme

the task of describingthese remains,and I am

in his debtformanykeensuggestionsboth

further

PROCEEDINGS

OF THE AMERICAN

PHILOSOPHICAL

SOCIETY,

as to restorationand interpretation.I wxishto

thankDr. W. M. Krogmanand his colleagueDr.

A. C. Henriques of the PhiladelphiaCenter for

Research in Child Growthfor carefullyoriented

x-rayphotographs

of skulland teeth,and to thank

my colleagueDr. J. E. Healey of the Baugh Instituteof Anatomyof the Jefferson

Medical Collegeforexcellentradiographsoftheskulland postcranial skeletons. Most of the daylightphotographs of the remains (all the good ones) were

takenby Mr. Reuben Goldbergof the University

Museum,who also assisted withassemblyof the

illustrations. Miss JaneGoodalehelpedbothwith

the original assembly of long bones and with

coordinating

therecordsas theyprogressed. Suggestionsof Dr. 0. V. Batson, Dr. K. S. Chouke,

Dr. C. W. Goff,Dr. W. M. Krogman,and Dr.

W. L. Straus are gratefully

acknowledged.

Numbers2 and 3 are theearlierskeletons,found

lyingpartlysupinewithheads togetherand lower

thantheirfootlesslegs at thebeginningof the 4th

gravels just above the underlyingsandy layer.

The positionsuggestscasual tumblingbackwards

and down froma higherlevel close to the cave

wall and does not negate the possibilityof accidentaldeath throughfall of rock disturbedby

these or other food-gatherers.Any possibility

that the corpses could have been buried froma

higherlevel is contradictedby the fact that the

thighsof number2 had been disarticulated(without shiftingthe shins or pelvis) and moved over

among the bones of number3. This could not

have happenedif the bodies had been coveredby

any greatamountof gravel. It suggeststhatthe

bodies largelydecomposedwhile lightlycovered

thoughweightedwith a few rocks,that mnenor

animals shiftedthe thighbones(and the lower

shins with feet ?), and that the ensuing burial

was throughnaturaldepositionof glacial gravels

beforedecompositionwas complete. Number 1,

on the other hand, was a deliberatesecondary

burial placed as a bundle at the top of the 4th

gravel layer, with some other skull fragments

lying nearby. The unusuallygood preservation

96, NO. 3, JUNE, 1952

258

VOL.

This content downloaded from 67.115.155.19 on Fri, 6 Dec 2013 23:00:01 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

VOL. 96, NO. 3, 19521

HUMAN SKELETAL REMAINS FROM HOTU CAVE

of the bony tissue is probablya result of their

remainingcontinuouslywet down to the time of

excavation:any extremealternationof dryingand

wettingwouldhave leachedaway thebones,which

were in any case both softand broken.

Thoughprobablyseparatedin timeby a number

of generationsall theHotu remainscan be treated

as one populationsample,in the same sense that

Morant (1929) and von Bonin (1935) have

groupedUpper PalaeolithicEuropeans. In both

cases identification

of actual huntingbands has

not been possible except to the extent that as

also at Hotu single cave groups may represent

breedingunitstied to one localityformanygenerations.

Number2 was a personabout 5' 6" tall (167.4

cm. staturereconstruction)with a muscularbut

slenderbuild indicatedby robustbonyridgesplus

a femoralrobusticity

indexof 11.9 showinga bone

with slender shaft. A sharp lumbarcurve (index 94.3) combineswitha tiltedsacrum (33 degrees for the upper 5 vertebraecompared to

modernnorm of 46 degrees). But the femoral

necksare also directedforward(29 degrees) more

thanusual (13 degrees),a featureunexpectedwith

a pelvic brim tilt as near verticalas 68 degrees

(57 degrees norm). Though the depth of the

pelvis would tend to place the acetabula in front

of the line of gravity,the extra degreeof femoral

neck torsionshould be linked with postural dynamics ratherthan statics. The upper surfaces

of the tibiae are tiltedmore than usual and the

laterallycompressedshaftsof the shinboneshave

a diamond-shape

crosssection. Fibulae are deeply

fluted. The femoraare distinctlyplatymericor

in the upper shaftas if to

thickenedtransversely

take stress fromstrongabductorand lateral rotator muscles. The deep gluteal fossae adjacent

to markedcrests,the strongadductortubercles,

thestressedoriginareas forgastrocnemius,

and on

the tibiae the increased origin area for deep

musclessupportingthe arches of the feetconfirm

the suggestionthat muscles involved in roughcountrytravel were well-developed. The hands

are long and narrow (ca. 187 x 69?), the shouldersprobablynotbroad (clavicle 142? and scapula

breadth94), and the hips narrow (256 bi-iliac).

The presacralvertebratemeasureabout 570 mm.,

includingestimatesfor intervertebral

disks, with

an additional138 anteriorarc forthe 6-vertebrae

sacrum. Though these are not far fromlanky

modernmale dimensionsand the skull makes a

male firstimpressionthe pelvis is clearlyfemale,

FIG.

259

1. Hotu No. 2, pelvis,lateral radiograph.

with deep "anthropoid"inlet (area 113.1) and

wide open outlet(area 106.3,interspinous

breadth

104?, and sub-pubic angle 88 degrees). The

sacro-sciaticnotches are large (37 x 61 with

posteriorsegment23 by Letterman'stechnique).

Pubic and ischial lengthsof 77 and 86, measured

externally(Washburn, 1948), are just on the

borderlineof the female categoryfor the white

race. But theextremely

deep and sharp-bordered

pre-auricular

sulciand theroughenedligamentand

rectusabdominisand aponeurosisattachments

on

the symphysial

area of pubic bones suggeststress,

perhapsfromcarryingchildren. Pubic symphysis

is earlyPhase V.

Thus this woman of about twenty-seven

years

was a real Amazon,stronger,taller,and slenderer

than average of ancient Greek, Medieval Norwegian,or modernAmericanwomen.

The pentagonoidskull vault is 75 to 100 cc.

larger than the 1,325 cc. modern average in

capacity,and is long and high withmarkedpostcoronal depression and concave and sinuous

temporalplanes,as if the infantilesharp curve of

the parietalbone had not been fullycorrectedby

laterperipheralremodelling. The cerebellararea

bulgesdownward,and theendocranialcast stresses

this vertical developmentand a somewhat ill-

This content downloaded from 67.115.155.19 on Fri, 6 Dec 2013 23:00:01 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

J. LAWRENCE ANGEL

260

FIG.

aspectof leftmaxilla.

2. Hotu No. 2, supero-medial

filledappearance. These linearvault featuresare

typicalof peoples foundacross the desertzone of

Africaand the Near East. But the broad skull

base (bi-auricular116), the relativelywide and

squat face (height105 withoutallowanceforteeth

but drooping

wear), the notablylow, rectangular,

(10 degrees) orbits,thesmallnose,and thealmost

horizontalchewingplane (2 degrees) combined

withsquare jaw angles and markedprotrusionof

chin are Cro-Magnon-likeand quite unlike the

deep, convex, beaky, sloping-jawed,and narrow

laterIranianface. Molar teethare nottaurodont.

Number 3 is the skeletonof a small, stocky,

overworkedwoman, about thirty-seven(pubic

Phase VII), and about 5' 2" tall (156.9

symphysis

cm.). She has relativelythickand bowedfemora,

and extra stresson the intertrochanteric

line and

insertionof the ilio-tibialband on the tibiae.

Otherwiseshe shows the same featuresof muscle

dynamicsas number2. The olecranonfossa of

the humerus is perforated,forearmbones are

bowed and wider set than number2's, the hands

are stubby(ca. 176 x 78), and thepelvisprobably

small and broad.

The bones seem slightlythinner

in cortexand less heavilytrabeculatedthanthose

[PROC. AMER. PHIL.

SOC.

arthritis

appearsin

of number2, and hypertrophic

the lumbar vertebralbodies, pelvic joints, and

hands. Both greater multangular-metacarpal

worn

jointsshowmarkedexostosesand eburnation

by excessive use of thumbsfor motionsof oppositionratherthan extension-flexion.And the

with

fifth

leftmetacarpaldistalshaftwas fractured

littledisplacementin healingbut markedflanging

of ligamentattachments.

The skullhas a strikingly

capaciousvault (14201460 cc.), ovoid, broad, well-filledwith wide-set

base (129 mm.) and approachingthe "squarehead" minorityamong Upper Palaeolithic and

laterEuropeans. The facehas wide cheeks,wide

nose, and a protrudingchin, and probably resemblednumber2.

skeleton of a

Number 1 is the fragmentary

massivemale, betweenthirtyand fortyyears old,

verymuscularand tall: over5' 9" (175.7 cm.based

on radius lengthof 261). In body build he was

probablythe male matchof number2. The skull

has strongand sharplycut browridges,sloping

forehead,flat temporalregion,arched nose profile,and exceedinglyheavymouth(palate 59 x 64,

chin35) withthe usual prominentHotu chinand

square-profiled

jaw angles. The lower toothrow

is wider than the upper. It is possible that this

skull fits directlybetween the modes of Upper

PalaeolithicEurope and ChalcolithicIran.

Number 4 is a left maxillaryfragmentof a

female ( ?) of about fifteenor sixteen,probably

witha widepalate and widernose and moreprognathismthannumber2.

Number 5 is a vault fragmentperhaps like

number3.

Thus the Hotu sample does show sharp variafound

tion, P)robal)lyequalling the heterogeneity

eitheramongEuropeanUpper Palaeolithichunters

or metalage Iraniansas wholes. Morantfindsthe

formerless variablethan seventeenth

centuryinhabitantsof London (1929: 135) in spite of the

slightsplitbetweenlinearand lateralskullformtendencies (cf. von Bonin,1935). And we need not

expectto findin eitherPalaeolithicor Chalcolithic

seen

North Iranians the degree of heterogeneity

in the Bronze Age and later in the Aegean area

(Angel, 1951). But a sharp contrastis suggested at Hotu betweena desert body built as

seen in number2 and a temperateor cold climate

stockybuild as seen in number3. This contrast

between linearityand large surface relative to

mass in desertenvironments

and the oppositein

cold climates though proven only for animals

This content downloaded from 67.115.155.19 on Fri, 6 Dec 2013 23:00:01 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

VOL. 96, NO. 3, 1952]

HUMAN SKELETAL REMAINS FROM HOTU CAVE

(Bergmann's and Allen's rules examined by

Rensch, 1936) fits roughlythe body build differencesseen in maps 5, 6, and 7 of Coon (1939:

251-279): Europeans as a whole are more massive and less dolichocephalicthan inhabitantsof

thewholedesertstripsouthof the Mediterranean.

Coon, Garn, and Birdsell (1950: 36-45) have

greatlyextendedthistheorybeyondthesuggestions

of Geyer (1932). And I have tried to show

(1949: 443) the probabilitythat Upper PalaeolithicEuropeanswereactuallyverymassivepeople

as suggested in exaggerated form by various

figurines(Burkitt,1939: 162-166; Martin,1928:

237-241). The experimentsof Ogle (1934) and

of MacArthurand Chiasson (1945) show how

boththe directeffectof climateand strongselection can produce through heterogonymarked

changes in adult body build. But where,as at

Hotu, we are dealingwitha singlepopulationwe

are more

may assume thatbody build differences

in origin.

likelyto be geneticthan environmental

On the otherhand such featuresas the Hotu

mouth and chin combination,the Cro-Magnonlike low orbits,the Iranian full cerebellum,and

perhapstrendstowardsacralhiatusand firstmolar

abscesspointto a certaingeneticunity,and plausibly "inbreeding." One would expect a small

and inbred population to show just such disin contrastto the

continuitiesand uniformities

"blended" variationof a large pan-mixedpopulation. This situation plus the double resemblances of the Hotu skeletonsto massive CroMagnons and to linear Iranians (cf. von Bonin,

1935 and Morant,1926, 1929 vs. Vallois, 1939 and

Morant, 1938) shows the kind of evolutionary

plasticityexpectedat thisdate in a peri-glaciallocality. There is even a possible resemblanceto

the old man and the large woman (Nos. 101 and

102) fromthe late Upper Palaeolithic at Chou

Kou Tien (Weidenreich, 1939). The changes

and connectionsimplied by these comparisons

would be a necessaryresultof geneticdriftplus

mixtureplus climaticselectionin a more or less

continuous chain of occasionally mixing small

breedinggroups. The theoriesworked out and

tested by Wright (1931, 1948), Dobzhansky

(1941, 1947), Huxley (1942: 40-44), and others

clearly apply here. I hope that the Hotu data

and comparisonsin the lightof these theoriesof

populationchange deal the coup de grace to the

outmodedhypothesis

ofracialoriginswhichsought

sources for later racial types (often imaginary)

FIG.

261

3. Hotu No. 2, top viewof lowerjaw.

fromsmall, "pure" inbredgroups in the distant

past. These sourcesjust do not exist.

In this cursoryanalysis I am using functional

unitslike the constrictedskullvault of the desert

zone or theunstressednasalia seen wherepalate is

horizontaland chewingthrustalmost verticalin

may turn

the hope thattheirgeneticdeterminants

out to be simple. We could then eliminatethe

measconfusionof arbitrary

presentcontradictory

urements,isolated details of form, and vague

types. To make any list of such units,however,

we need not only a deeper knowledgeof human

genetics but also to know betterhow far one

mechanicallydominantregionof the body affects

adjacent regionsand how plastic the body is in

adaptingto all kindsof stressduringgrowth. In

the presentinstancemost of the multipleIranian

versus Cro-Magnonfacial contrastseems to depend directlyon verticalgrowthat nose-forehead

junction versus jaw condyle,in relationto the

anteriorskull base: in Hotu number2 both the

anteriorskull base and the occlusal plane come

closer than usual to paralleling the Frankfort

plane whereas in the later Iranians, with their

buttressingnoses, the chewingplane, and probably also the anteriorskull base, slope forward

sharplyaway fromthe Frankfortplane as also in

Neanderthalman and the Eskimo. The Hotupeople seem to have been adequately nourished

(tall statureand deep pelvis), but have flattened

shaftsof long bones and extra ridgesto increase

surfacefor muscle origins,as seen in almost all

prehistoricand manyprimitivepeoples. To test

how much the facial patternis geneticand will

respondto genic loss and selectionand how far

This content downloaded from 67.115.155.19 on Fri, 6 Dec 2013 23:00:01 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

262

J. LAWRENCE

ANGEL

[PROC. AMER. PHIL. SOC.

_l.I

l

Iil

-

Wark_

..

' t '' ;.d'

,',' '

! .

t,7,

''

'

'

,,

'

,

.

,,'

................

as

0'- ,' ' I_

t

.

,-

'

'

'

.:

'^,

'.

_d

000

0OFFIG.4. HotuNo. 2, right

profile,

front,

andbackviewsofskull.

This content downloaded from 67.115.155.19 on Fri, 6 Dec 2013 23:00:01 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

en7

VOL. 96, NO. 3, 1952]

HUMAN SKELETAL

REMAINS

FROM HOTU CAVE

FIG. 5. Hotu No. 2, leftprofile,

basal,and topviewsof skull.

This content downloaded from 67.115.155.19 on Fri, 6 Dec 2013 23:00:01 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

263

J. LAW;RENCE ANGEL

264

FIG06.

HouN

.

3,. letpoie

akadtpvesofsulbfr

[PROC. AMER. PHIL. SOC.

fP;I

aersoain

This content downloaded from 67.115.155.19 on Fri, 6 Dec 2013 23:00:01 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

VOL. 96, NO. 3, 1952]

HUMAN SKELETAL REMAINS FROM HOTU CAVE

265

FIG. 7. Hotu No. 1, upper and lower jaws with teeth, before furtherrestoration.

muscle use is environmentaland only weakly

responsiveto selection demands animal experiments.

Furtherspeculationsin the social biologyof the

Hotu group are interesting.All threeyoungish

adults describedhave sufferedfrom peri-apical

abscesses of the upper firstmolar alveolae extensive enough to invade the maxillary sinus.

This is clearlyseen on the leftside of the palate

of number2, in whoma secondarydrainagepathway openedin the caninefossa 11 mm.below the

infraorbital

foramenafterthewall ofthemaxillary

sinus had been thickenedto 1.5 mm. by the inflamedmucoperiosteum.Though some inherited

factoraffectingdentine reaction may be partly

responsible,this abscess formationis chieflya

resultof excessiveteethwear,amountingto about

1 mm. every five years in the molar region of

number2. Dietary conditionsmust have been

trulyeskimoidto produce such abscesses mechanicallyratherthan throughtoothdecay.

Femoral necktorsion,tibialhead tilting,gluteal

This content downloaded from 67.115.155.19 on Fri, 6 Dec 2013 23:00:01 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

J. LAWRENCE ANGEL

266

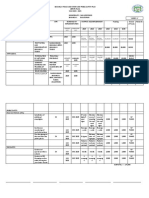

TABLE

[PROC. AMER. PHIL. SOC.

MEASUREMENTS OF HOTU FEMALE SKULLS COMPARED WITH MEANS OF OTHER GROUPS

Area....................................

Iran

Cultureperiod...........................

Upper Palaeolithic

Chalcolithicand

Copper Age

Upper Palaeolithic

Medieval

Hotu

Sialk, Hasan

West and Central

Oslo, Norway

Coon and Angel

Vallois, Morant

V. Bonin, Morant

Schreiner

Site.....................................

Authorities

..............................

No. 2

Cranial capacity (seed)

Horizontal circumference

Transverse arc

Sagittal arc (total)

Frontal arc

Parietal arc

Occipital arc

Europe

No. 3

1,404cc. 1,440?

520

505

309

309

388

382

127

135

137

129

114

118

1,293

502.2

296.0

372.3

125.5

129.9

116.3

(calc.)

8

3

6

4

4

3

186

(104)

(139)

120

135

116+

116?

116

93+

129?

99+?

184

(95)

(138)

120143

128+

123??

118

97

138??

(99)

179.7

95.5

129.2

111.5 +

132.7

(narrow)

113.0

113.0

92.6

122.7

94.2

3

10

10

5

4

Face height (total)

Chin height

Upper face ht. (na.-pr.)

Nose height

Nose breadth

Interorbitalbreadth

Orbit breadth (dacryon)

Orbit height

Palate length (external)

Palate breadth (external)

Ramus heightjaw

Least ramus breadth

105

34

65

4621+

20

38

28

56

62

65?

35

(103)

33??

61?

44.5?

26?

(23)

40?

31+?

53-?

63?

(65)

30

116.5

(34.5)

66.5

49.0

24.3

18.0

39.5

32.6

2

2

5

4

4

2

5

5

Jaw angle

Facial profileangle

Nasal bones profile

110

88

(65)

(112)

88?

110.7

84.5

Cranial length (gl.-occ.)

Base length (bas.-nas.)

Basion-bregma height

Auricular-vertexht.

Maximum vault breadth

Base breadth (bi-auric.)

Bicondylar breadth jaw

Maximum frontalbreadth

Minimum frontalbreadth

Face breadth (bizygomatic)

Jowl breadth (bigonial)

Cranial 1-br.index

Mean auric. ht. index

Frontal-parietal br.

Cranio-facial br. index

Upper face ht.-br. index

Nasal ht.-br. index

Orbital index (dacryon)

72.6

74.8

68.9

95.6?

50.4?

45.7

73.7

77.7

73.9

67.8

96.5??

44.2?

58.4?

77.5?

74.0

71.4+

70.2

90.1

53.3

49.9

82.4

12

3

3

6

12

1,374

524.6

306.2

372.9

125.2

127.7

121.0

(calc.)

11

7

10

13

14

10

185.6

100.1

132.4

112.1

138.2

(wide)

12

9

9

5

13

117.6

97.3

129.4

13

13

5

(34 ca.)

65.9

48.5

25.6

7

8

10

(40.5)

29.9

8

10

4

4

84.8

12

6

10

5

4

4

5

74.9

69.2?

70.3

93.6

50.9

53.3

(73.8)

11

*

12

*

*

7

*

1,302.6

506.3

301.0

360.0

123.8

121.9

114.6

326

538

495

536

561

567

544

179.3

96.5

126.2

108.9+

135.8

119.0

113.0

114.8

93.5

124.5

94.6

572

479

489

500

555

496

109

434

546

284

97

110.7

30.2

67.2

48.8

23.5

20.6

(38.4)

33.4

50.2

60.3

58.4

31.6

109

101

325

335

311

326

345

346

254

248

113

113

121.3

84.4

56.2

1ll

l

1 281

211

75.8

69.1?

69.0

91.7

54.1

48.1

(87.0)

553

531

276

262

302

338

Note: Presumably 1 mm. should be added to the auricular height (OH) of Chalcolithic Iranians and almost 1.5

mm. added to the auricular-bregmaheightsof the European series to equate the porion-vertexdimension used for Hotu.

An attempt has been made to correctthe European series orbital breadths to equate dacryon-ectoconchion. Figures in

parenthesesare estimatesand not reliable forstatisticalpurposes. 5 mm. have probablybeen lost fromtotal facial height

throughincisor teeth wear of Hotu No. 2. and No. 3: the amount of compensatoryalveolar growthis not determinable.

This content downloaded from 67.115.155.19 on Fri, 6 Dec 2013 23:00:01 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

VOL. 96, NO. 3, 1952]

HUMAN SKELETAL REMAINS FROM HOTU CAVE

TABLE

267

MEASUREMENTS OF HOTU FEMALE SKELETONS COMPARED WITH MEANS OF OTHER GROUPS

Site.............................................

Hotu

No. 2

U.S.A. Modern

No. 3

320.3

Humerus, Max. length

Max. midshaftthickness

Min. midshaftthickness

Bi-epicondylar br.

Radius, Max. length

Ulna, Max. length

Forearm max. breadth

Femur, Max. length

Bicondylar length

Max. diam. head

fA-post.

Subtrochanter )~Transv.

(315)

22

16

53238

260

42

461

455

43.5

25.5

31

(297?)

21

14

58

208

233

(44)

396391+

40.5

22.5

28.5

Midshaft A-post.

lTransv.

Distal epiphysis br.

Neck torsion angle

Tibia, L.c. length

Nt

for.level{A-post.

Nutr

fo. lvelTransv.

Retroversionangle

Pelvis

Innominate height

Innominate breadth

Bi-iliac breadth

27.5

26.5

74

29

(358?)

32.5

21

10.5

26

24

73

31

(305?)

33.5

21

13.5

Inlet

of true pelvis fA-post.

Inlet

Transv.

rAnt.-post.

Outlet of true pelvis Intertuberous

Interspinous

Pubic length

Ischial length

Sciatic notch breadth

Sciatic notch height

Sciatic notch post. segt.

Pelvic brim tilt

Sacral height

Sacral breadth

Lumbar Vertebrae Hts.

Anteriorheights

Posterior heights

Indices

Humeral flatness

Platymeric (femur)

Pilastric (femur)

Robusticity (femur)

Cnemic (tibia)

Pelvic inlet

Vertical lumbar (curve)

Stature reconstructed

(Dupertuis' general formula)

207

154

256

189

(136)

121

119

109, 120 at S5

125

104?

77?

(82)

86?

79?

61

55

37

33

23

24=

68

118, 108 for5

(111)

U. Pal. Europe

M

NorwayMed.

M

100

310.5

20.9

16.2

312

312

312

217.8

100

233.1

251.2

171

133

422.4

417.6

100

23.9

29.4

28

28

417.4

42.6

24.0

29.2

493

415

497

498

26.4

25.8

28

28

25.6

25.1

499

499

338.9

100

12.7

333.1

437

544

7.4

379

77.7

82.2

102.1

12.2

312

498

499

161.0

202.0

157.3

270.5

20

20

20

122.4

130.6

119.7

109.0

99.5

77.9

78.3

51.9

30.9

27.6

57.7

101.8

117.5

500

500

500

500

500

100

100

106

106

106

500

25

25

139?

133?

72.7

80.6

103.8

11.9

64.6

101.7

95.7?

66.7

79.0

108.3

12.7

62.7

79.3

770

81.1

28

101.7

28

12.5 ca.

(72) ca.

93.9

500

96.2

43

males

167.4 cm.

156.9

161.0

100

both sexes

74.5

116.0

16

8

64.6

16

females

155 ca.

5

Note: Authoritiesfor the composite series of modern white female data include: Dupertuis and Hadden, Hrdlicka,

Young and Ince, Letterman,Washburn, Todd and Pyle; Von Bonin recordsthe Upper Palaeolithic indices, and Wagner

the Norwegians.

This content downloaded from 67.115.155.19 on Fri, 6 Dec 2013 23:00:01 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

268

J. LAWRENCE ANGEL

[PROC. AMER.

PHIL.

SOC.

pressures. But life was certainlyhazardous, if

one follows the indicationthat the two Hotu

womenwere killed by a rock fall.

From the social standpointthis gives a picture

of a small band of gathererswith littleleisure,

where every one worked at top capacity,where

childrenwere treated well, fed as regularlyas

possible, and valued',where strangersmightbe

admitted,wherephysicalexuberancewas admired,

and where accident rather than disease might

cause death.

From thebiologicalstandpointtheHotu sample

places modernman definitely

on the edge of the

steppezone as well as in the caves and ambushes

of Europe,of China,and of NorthAmericaduring

theretreatofthelastglaciation. This raisesthree

FIG. 8. Radiographs

of hands. Hotu No. 3 (left) with questions: 'How wide, how rapid, and how

rightthumbadded; Hotu No. 2 (right) with leftfifth disastrous were migrationsof our huntinganmetacarpalsubstituted.Note pathologicchangesin No. cestors? How important

was individualinitiative

3 at head of fifth

metacarpaland firstmetacarpal-greaterin such groups? How old and how selected is

multangular

joint.

modernman?"

REFERENCES

crest development,platymeria,platycnernia,

and

stressed extensor and rotatormuscle insertions ANGEL, J. L. 1949. Constitution in female obesity.

forma complex (cf. Wagner, 1926: 115-117)

Amer Jour Phys. Anthrop.,n. s. 7: 433-458.

1951. Population size and microevolutionin

called the bent-kneegait, often misinterpreted.

Greece. Cold Spring Harbor Symposia on Quant.

This appliesto use ofthelegs flexibly,

likea skier,

Biol. 15: 343-351.

and not a posture. Stress on the ilio-tibialband, BONIN, G. VON. 1935. European races of the

Upper

iliac crest, and lower and upper lumbar areas

Palaeolithic. Human Biology 7: 196-221.

(possibleherniationof lowestnucleuspulposusin BURKITT, M. C. 1933. The old stone age. A study of

Palaeolithic times. Cambridge,England, Univ. Press.

number2) suggestsfurther

thatthe Hotu women

may have done some standingand workingwith COON,C. S. 1939. The races of Europe. N. Y., Macmillan.

braced legs (as pullingon a fishnet) as well as

. 1951. Cave explorations in Iran 1949. Museum

muchclimbingin roughcountry,

carrying,

and digMonographs, The U;niversityMuseum, Philadelphia.

ging. The injuriesto the thumb-wrist

joints and COON, C. S., S. M. GARN, and J. B. BIRDSELL. 1950.

Races. A study of the problems of race formation

littlefingerof number3 suggestpossiblefighting

in man. Springfield,Ill., Thomas.

butmoreplausiblyhardmanualworkperhapsmore

DOBZIIANSKY, Tii., 1941. Genetics and the origin of

specializedthan diggingfor roots: flint-chipping, species. 2nd ed. N. Y., Columbia Univ. Press.

plaiting baskets, net-making,or possibly mid. 1947. Adaptive changes induced by natural selection in wild populations of Drosophila. Ezvolution1:

wiferyor shamanism. The pelves of the two

1-16.

womenshow enoughbone reactionat ligamentattachmentsand insertionof the abdominal wall DUPERTUIS, WV.C., and J. A. HADDEN, JR.,1951. On the

reconstructionof stature from long bones. Anmer.

muscles(rectusand externalobliqueaponeucosis)

Joztr.Phys. Winthrop.,

ii. s. 9: 15-53.

to hint that pregnancymay have been frequent GEYER, E. 1932. Die anthropologischenErgebnisse der

and withoutrest period. No lines of arrested

mit Uiiterstutzungder Akademie der Wissenschafteni

in Wien veranstaltetenLapplandexpedition 1913/14.

bone growthoccur,thoughone mightimaginethe

Mitt. d. Anthr. Ges. Wien 62: 163-209.

lack ofparietalremodelling

and a traceofoccipital HRDLICKA, A.

1916. Physical anthropologyof the Lenape

pittingin number2 as evidencesof a barelyadeor Delawares, and of the eastern Indians in general

Bur. Amer. Ethnol. Bull. 62.

quate diet. Perhaps it was a diet more than

adequate in toto but undergoingmarkedfluctua- HUXLEY, J. 1942. Evolution. The modern synthesis

London, Allen & Unwin.

tions with the game supply. At any rate life

LETTERMAN, G. S. 1941. The greater sciatic notch in

expectancymay not have been less than in NeoAmerican whites and negroes. .A4mer.Joker.Phys.

lithictimes in spite of these physicaland social

Anthrop.28: 99-116.

This content downloaded from 67.115.155.19 on Fri, 6 Dec 2013 23:00:01 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

VOL. 96, NO. 3, 1952]

HUMAN SKELETAL REMAINS FROM HOTU CAVE

MAcARTHUR,J. W., and L. P. CHIASSON. 1945. Relative growth in races of mice produced by selection.

Growth9: 303-315.

MARTIN, R.

1928. Lehrbuch der anthropologie. 3 v.

Jena, G. Fischer.

MORANT, G. M. 1926. Studies of Palaeolithic man. I.

The Chancelade skull and its relation to the modern

Eskimo skull. Annals of Eugenics 1: 257-276.

. 1929. Studies of Palaeolithic man. IV. A biometric study of the Upper Palaeolithic skulls of

Europe and of their relationshipsto earlier and later

types. Annals of Eugenics 4: 109-214.

. 1938. A description of nine human skulls from

Iran excavated by Sir Aurel Stein, K. C. I. E. Biometrika 30: 130-133.

OGLE, C. 1934. Climatic influenceon the growth of the

male albino mouse. Anmer.Jour. Physiol. 107: 635-

640.

B. 1936. Studien uber klimatische Paralleitat der Merkmalsauspragung bei V6geln und

Siugern. Archiv f. Naturgesch., n. f. 5: 317-363.

SCHREINER, K. E. 1939. Crania Norvegica. I. Inst. f.

Sammenl. Kulturf.,Ser. B. Skr. 36. Oslo.

RENSCH,

269

TODD, T. W., and S. I. PYLE. 1928. A quantitative

study of the vertebral column by direct and

roentgenographic methods. Amer. Jour. Phys.

Anthrop. 12: 321-338.

VALLOIS,H. V. 1939. Les ossements humains de Sialk.

In R. Ghirshman,Fouilles de Sialk 1933, 1934, 1937.

II. Louvre Dept. des Antiquitcs Orientales Serie

Archtologique 5: 113-192, Paris.

WAGNER,

K.

1926. Mittelalter-Knochen aus Oslo.

Skrifter Norske Videnskapsakademi i Oslo, I, MatNaturv. Ki. 2 (7).

WASHBURN,

S. L. 1948. Sex differencesin the pubic

bone. Anzer. Jour. Phys. Anthrop.,n. s. 6: 199-208.

WEIDENREICH,

F. 1939. On the earliest representatives

of modernmankindrecoveredon the soil of East Asia.

Peking Nat. Hist. Bull. 13: 163-174 (part 3).

WRIGHT,

S. 1931. Evolution in mendelian populations.

Genetics 16: 97-159.

1948. On the roles of direct and random changes

in frequencyin the genetics of populations. Evolution

2: 279-294.

YOUNG, M., and J. G. H. INCE.

1940. A radiographic

comparison of the male and female pelvis. Jour.

Anat. 74: 374-385.

This content downloaded from 67.115.155.19 on Fri, 6 Dec 2013 23:00:01 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

You might also like

- Aromatase and BPADocument7 pagesAromatase and BPAWesley MuhammadNo ratings yet

- 19770523Document16 pages19770523Wesley MuhammadNo ratings yet

- Adams 1Document5 pagesAdams 1Wesley MuhammadNo ratings yet

- AdrosteroneDocument4 pagesAdrosteroneWesley MuhammadNo ratings yet

- 19770523Document16 pages19770523Wesley MuhammadNo ratings yet

- Drugs 8Document10 pagesDrugs 8Wesley MuhammadNo ratings yet

- Aromatization of Androgens Simpson FS 02Document5 pagesAromatization of Androgens Simpson FS 02Wesley MuhammadNo ratings yet

- ArticleDocument12 pagesArticleWesley MuhammadNo ratings yet

- Bpa 1Document9 pagesBpa 1Wesley MuhammadNo ratings yet

- Drugs 7Document6 pagesDrugs 7Wesley MuhammadNo ratings yet

- BPA PCaDocument12 pagesBPA PCaWesley MuhammadNo ratings yet

- AggressionDocument16 pagesAggressionWesley MuhammadNo ratings yet

- Hyperserotonemia in Autism: The Potential Role of 5HT-related Gene VariantsDocument6 pagesHyperserotonemia in Autism: The Potential Role of 5HT-related Gene VariantsWesley MuhammadNo ratings yet

- Black Men Testosterone 14Document7 pagesBlack Men Testosterone 14Wesley MuhammadNo ratings yet

- Afrocentricity 1Document18 pagesAfrocentricity 1Wesley MuhammadNo ratings yet

- William HerrmannDocument68 pagesWilliam HerrmannWesley MuhammadNo ratings yet

- Black Maculinity 1Document31 pagesBlack Maculinity 1Wesley Muhammad100% (1)

- South African Archaeological SocietyDocument15 pagesSouth African Archaeological SocietyWesley MuhammadNo ratings yet

- Amygdala: Eyes Wide Open: Current Biology Vol 24 No 20 R1000Document3 pagesAmygdala: Eyes Wide Open: Current Biology Vol 24 No 20 R1000Wesley MuhammadNo ratings yet

- Autism 1Document13 pagesAutism 1Wesley MuhammadNo ratings yet

- Ra IZ Allah Status Quaestionis ReportDocument30 pagesRa IZ Allah Status Quaestionis ReportWesley Muhammad100% (4)

- Jonathan Smith 1Document26 pagesJonathan Smith 1Wesley MuhammadNo ratings yet

- Blond, Tall, With Honey-Colored Eyes Jewish Ownership of Slaves in The Ottoman EmpireDocument19 pagesBlond, Tall, With Honey-Colored Eyes Jewish Ownership of Slaves in The Ottoman EmpireBlack SunNo ratings yet

- Svayambhu PuranaDocument9 pagesSvayambhu PuranaMin Bahadur shakya88% (8)

- Buddha GodDocument3 pagesBuddha GodWesley MuhammadNo ratings yet

- Great Buddha 3Document8 pagesGreat Buddha 3Wesley MuhammadNo ratings yet

- Avrospatt Sacred Origins of The Svayambhucaitya JNRC 13 2009 PDFDocument58 pagesAvrospatt Sacred Origins of The Svayambhucaitya JNRC 13 2009 PDFGB ShresthaNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- MicrosystemDocument5 pagesMicrosystembabalalaNo ratings yet

- Everything You Need to Know About VodkaDocument4 pagesEverything You Need to Know About Vodkaudbhav786No ratings yet

- Weekly Home Learning Plan: Grade 8 - Quarter 2. Week 7Document3 pagesWeekly Home Learning Plan: Grade 8 - Quarter 2. Week 7Danmer Jude TorresNo ratings yet

- Barangay Ordinance Vaw 2018Document7 pagesBarangay Ordinance Vaw 2018barangay artacho1964 bautista100% (3)

- Fall ProtectionDocument5 pagesFall ProtectionAamir AliNo ratings yet

- Prevention of Surgical Site Infections: Pola Brenner, Patricio NercellesDocument10 pagesPrevention of Surgical Site Infections: Pola Brenner, Patricio NercellesAmeng GosimNo ratings yet

- Exudate Detection For Diabetic Retinopathy With Circular HoughDocument7 pagesExudate Detection For Diabetic Retinopathy With Circular HoughAshif MahbubNo ratings yet

- Thalassemia WikiDocument12 pagesThalassemia Wikiholy_miracleNo ratings yet

- HRLM - Catalogue # Ex Apparatus - AC-Z Series Explosion Proof Plug and ReceptaclesDocument2 pagesHRLM - Catalogue # Ex Apparatus - AC-Z Series Explosion Proof Plug and Receptaclesa wsNo ratings yet

- Manual Murray 20Document28 pagesManual Murray 20freebanker777741No ratings yet

- Us Errata Document 11-14-13Document12 pagesUs Errata Document 11-14-13H VNo ratings yet

- Bioreactor For Air Pollution ControlDocument6 pagesBioreactor For Air Pollution Controlscarmathor90No ratings yet

- An Island To Oneself - Suvarov, Cook Islands 2Document8 pagesAn Island To Oneself - Suvarov, Cook Islands 2Sándor TóthNo ratings yet

- Aripiprazole medication guideDocument3 pagesAripiprazole medication guidemissayayaya100% (1)

- ECOSIADocument8 pagesECOSIAaliosk8799No ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0975947621001923 MainDocument8 pages1 s2.0 S0975947621001923 Mainaman babuNo ratings yet

- Gimnazjum Exam Practice GuideDocument74 pagesGimnazjum Exam Practice GuideVaserd MoasleNo ratings yet

- Atlas Copco Generators: 15-360 kVA 15-300 KWDocument10 pagesAtlas Copco Generators: 15-360 kVA 15-300 KWAyoub SolhiNo ratings yet

- Unit Test-Unit 5-Basic TestDocument2 pagesUnit Test-Unit 5-Basic Testphamleyenchi.6a8txNo ratings yet

- Auxiliary Range: CLR - High Speed Trip Lockout RelayDocument2 pagesAuxiliary Range: CLR - High Speed Trip Lockout Relaydave chaudhuryNo ratings yet

- My PRC Form-Censored Case NumbersDocument5 pagesMy PRC Form-Censored Case NumbersLeah Lou Gerona MontesclarosNo ratings yet

- Maxicare Individual and Family ProgramDocument43 pagesMaxicare Individual and Family Programbzkid82No ratings yet

- Food Sample Test For Procedure Observation InferenceDocument2 pagesFood Sample Test For Procedure Observation InferenceMismah Binti Tassa YanaNo ratings yet

- Asbestos exposure bulletinDocument2 pagesAsbestos exposure bulletintimNo ratings yet

- Nursing Philosophy ReflectionDocument7 pagesNursing Philosophy Reflectionapi-480790431No ratings yet

- Barangay Peace and Order and Public Safety Plan Bpops Annex ADocument3 pagesBarangay Peace and Order and Public Safety Plan Bpops Annex AImee CorreaNo ratings yet

- Flexo Uv Ink TroubleshootingDocument22 pagesFlexo Uv Ink TroubleshootingHiba Naser100% (1)

- ISO 9001 2008-List of Sample Audit QuestionsDocument5 pagesISO 9001 2008-List of Sample Audit QuestionsSaut Maruli Tua SamosirNo ratings yet

- 310 Ta PDFDocument8 pages310 Ta PDFVincent GomuliaNo ratings yet

- The Refugees - NotesDocument1 pageThe Refugees - NotesNothing Means to meNo ratings yet