Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Frutos Secos y Sus Propiedades Funcionales Desde El Punto de Un Consumidor

Uploaded by

Olivia Tapia LagunaCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Frutos Secos y Sus Propiedades Funcionales Desde El Punto de Un Consumidor

Uploaded by

Olivia Tapia LagunaCopyright:

Available Formats

Journal of Horticultural Science & Biotechnology (2009) ISAFRUIT Special Issue 8588

Dried fruit and its functional properties from a consumers point

of view

By K. JESIONKOWSKA1*, S. J. SIJTSEMA2, D. KONOPACKA1 and R. SYMONEAUX3

Research Institute of Pomology and Floriculture, 18 Pomologiczna Street, 96-100 Skierniewice,

Poland

2

LEI Wageningen University and Research Centre, Hollandseweg 1, 6706 KN Wageningen,

The Netherlands

3

Association Groupe ESA-Labo GRAPPE, 55 rue Rabelais, 49 007 Angers Cedex 01, France

(e-mail: kjesion@insad.pl)

(Accepted 31 August 2009)

SUMMARY

Modern drying technology provides the opportunity to obtain dried fruits with high concentrations of bioactive

compounds. Such products may also be fortified with functional ingredients. The adoption of dried fruit as a carrier of

functional ingredients for consumers is indispensable to launch this kind of product successfully on the market. Thus,

the aim of this study was to collect data on consumer perceptions and interests in dried fruits (plain or fortified)

through a questionnaire distributed on the Internet to 1,092 Dutch, French, and Polish respondents. In this quantitative

study, the respondents were first asked to rank statements about a product with different positive influences on human

health. Products which lowered the risk of cancer or heart diseases were mainly of interest to Polish and Dutch

respondents, whereas French consumers emphasised the prevention of intestinal problems. Furthermore, we checked

the level of consumer interest in dried fruits enriched with a particular functional ingredient (e.g., anti-oxidants,

natural fruit sugars, or prebiotics). Products with anti-oxidants seemed to be the most promising in all three countries

investigated. Among five different forms of product (i.e., candy, fruit teas, cereals, bars, or cookies) in which dried fruit

could be incorporated, cereals were selected by approx. 33% of all respondents as the best product to which a

functional dried fruit could be added. In summary, dried fruits can be adopted as carriers of functional ingredients,

especially when promoted as a source of anti-oxidants.

xploitation of dried fruit as a carrier of functional

ingredients is a relatively new concept, although the

functional properties of such products originated from

the nature of drying process, where the removal of water

leads to a natural concentration of healthy fruit

components. Even taking into consideration the fact that

traditional drying technology leads to serious losses of

bioactive compounds, dried fruit can still be a valuable

source not only of energy, dietary fibre and minerals, but

also of anti-oxidant activity. Natives in Canada used to

dry berries in order to have enough vitamin C during the

off-season to protect them against scurvy (Turner, 1997).

Due to the application of modern technology, the matrix

of fruits and vegetables can be fortified with healthpromoting compounds such as prebiotics, vitamins, or

minerals. This is considered to be an important area for

future research into the development of functional food

markets (Alzamora et al., 2005; Fito et al., 2001). Based

on the natural potential of fruit, and the opportunities

offered by modern technology, the idea arose within the

ISAFRUIT Integrated Project to develop novel,

convenient, dried fruit products with functional

properties that could contribute to the increased

consumption of healthy products.

New food product development, especially those with

functional properties, represents a high risk for any

company (van Trijp and Steenkamp, 2005; van Kleef

*Author for correspondence.

et al., 2002; 2005). Statistics show that many functional

food products, even when developed from a sound

scientific point of view, encounter poor market

acceptance (Hilliam, 1998). Approx. 75% of newlylaunched food products are withdrawn from the food

market during their first 2 years (Menrad, 2003).

Consumer acceptance of a specific functional ingredient

is linked to consumer knowledge of its health effects,

thus, the first essential step in product development is to

explore which diseases consumers are actually

concerned about (van Kleef et al., 2005; Menrad, 2003).

To consume functional foods, consumers also need to

know what benefit they will get from consuming a

particular food, and why (Wansink et al., 2005). For many

years, in the European Union, using disease-related

information on packages or in product advertisements

for a functional food was forbidden (Menrad, 2003). In

July 2007, regulations on the nutritional and health

claims that can be made for a food were introduced (EC

Reg. No. 1924/2006). This provides the food industry with

new legislation opportunities to design innovative

products with added nutritional value (Schaafsma and

Kok, 2005). Apart from the proper formulation of health

claims, the product should also be presented in an

attractive form so that consumers can accept easily it

(van Kleef et al., 2005).

To increase the chance of consumer adoption of any

novel dried-fruit product, this quantitative study was

undertaken to address consumer perceptions of dried

86

Dried fruit and its functional properties

fruit (plain or fortified). The main aim of this study was

to obtain information on consumer perceptions of dried

fruit as a carrier of functional properties, taking into

account consumer interest in different functional

ingredients as well as the form of product in which a

dried fruit with functional properties could be

incorporated. The investigations were carried out among

Dutch, French, and Polish respondents, who declared

consumption of dried fruit, or products with dried fruit,

at least once a month.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

In total, 1,092 consumers from France, The

Netherlands, and Poland took part in the survey

concerning dried fruit and dried fruit products. The

questionnaire was originally sent to 1,217 respondents

through the Internet. The data presented in this article

concern only the functional properties of dried fruits and

food products in general. Respondents who were in the

habit of eating dried fruit at least once a month were

targeted. The Dutch respondents seemed to be less

familiar with dried fruit than the Polish respondents

(Jesionkowska et al., 2007). Therefore, consumers who

also declared they ate products containing dried fruit,

such as cookies and cereals, at least once a month were

taken into account.

Formulation of the questionnaire

To have an insight into whether or not consumers

perceived dried fruit as a source of nutritional

ingredients, respondents were asked to express their

level of agreement with the following five statements:

I eat dried fruits because they are a source of vitamins

I eat dried fruits because they are a source of sugar

I eat dried fruits because they are a source of minerals

I eat dried fruits because they are a source of fibre

I eat dried fruits because they are a source of energy

Only respondents who declared dried fruit

consumption answered this question.

Positive or negative attitudes to statements concerning

nutritional ingredients were marked on a 5-point Likert

scale (1 = I totally agree, to 5 = I totally disagree).

Moreover, the possibilities: I dont know and No

answer were also available.

For data analysis, the scale was reversed to facilitate

graphic presentation of the results.

Respondents also had to rank functional products

with a particular beneficial influence on human health

from the most interesting (1), to the least interesting (5).

The following descriptions were presented to the

respondents:

Products which prevent intestinal problems

Products which lower the risk of heart illness

Products which lower the risk of cancer

Products which do not cause tooth decay

Products which give you energy in a natural way

Later, two questions concerning dried fruit as a carrier

of functional ingredients were asked. Anti-oxidants,

natural fruit sugars, and prebiotics were taken into

account as they can easily be offered with dried fruit.

These ingredients were chosen based on technological

premises. Anti-oxidants (e.g., vitamin C, anthocyanins)

occur in abundance in certain fruit species (e.g., sour

cherries, blackcurrants) and, due to modern drying

technology, can be concentrated; while prebiotics and

natural fruit sugars can easily be added during a process

of osmotic infusion.

To be sure that all the respondents understood the

influence of the functional ingredients mentioned on

human health, a short description of each particular

ingredient was attached. The level of consumer interest

was measured on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = extremely

interesting; 5 = not at all interesting). The answers I

dont know and no answer were also available. In this

case, the scale was also reversed for data analysis.

As dried fruit with functional properties can be a

component of other products, respondents were asked to

choose the best form of product (e.g., candy-like, fruit teas,

breakfast cereals, muesli bars, or cookies) in which dried

fruit with functional properties could be incorporated.

Statistical analysis

To evaluate the differences between the three

nationalities, one-way ANOVA was used. Moreover, a

post-hoc Duncans MRT test was performed to check

whether there were differences between particular

statements within one nationality.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Perception of dried fruit as a carrier of nutritional values

A summary of the data concerning respondent

motivations for dried fruit consumption is presented in

Figure 1. Polish respondents were most positive about all

statements describing dried fruit as a source of

nutritional ingredients. Dutch consumers were negative

about the statement that they ate dried fruit because it

was a source of sugar, and neutral when it came to the

sentence that dried fruits were sources of minerals. All

nationalities claimed that they ate dried fruit mainly

because it was a source of energy. This is in agreement

with the perception of one of the most popular dried

fruits, plums, which are a good source of energy

(Stacewicz-Sapuntzakis et al., 2001). However, Dutch

I eat dried fruit because they are a source of...

Vitamins

*

*

Sugar

Minerals

Fibre

Energy

Dutch respondents (n = 185)

French repondents (n = 186)

Polish respondents (n =321)

I totally disagree

Neither agree nor disagree

I totally agree

FIG. 1

Levels of consumer agreement towards statements concerning their

consumption of dried fruit because of the presence of certain nutritional

ingredients. An asterisk denotes significant differences between

nationalities at P 0.05. The insert in the top left-hand corner shows the

outcomes of Duncans MRT test. Ingredients marked with the same lowercase letter do not differ significantly within one nationality at P 0.05.

K. JESIONKOWSKA, S. J. SIJTSEMA, D. KONOPACKA and R. SYMONEAUX

Consumer interest in dried fruit with certain functional properties

respondents appreciated the presence of fibre in dried

fruit more than energy, whereas Polish consumers mostly

preferred dried fruit as a source of vitamins. In contrast,

French consumers agreed less with the statement that

they ate dried fruit because it was a source of vitamins.

I am not at all interested

Neither interested nor uninterested

oxidants on human health.

Although all nationalities claimed that they ate dried

fruits for energy, dried fruit with added natural fruit

sugars was perceived as the least interesting. Possibly, the

word energy, which evokes more positive connotations,

should replace the word sugar.

Consumer preferences towards the form of a product

with dried fruit

Both the substance used for enrichment, and the type

of product being enriched, strongly affected consumer

attitudes towards functional products (Jonas and

Beckmann, 1998; Poulsen, 1999). Thus, consumer

preferences towards the form of a product with dried

fruit containing three different functional ingredients

were measured (Figure 4). Approx. 33% of all

respondents preferred cereal as the form of product in

which dried fruit with anti-oxidants or prebiotic

additions could be incorporated. Dutch respondents

were also in favour of cookies, whereas Polish

respondents preferred fruit teas. This finding may

100

8.3

39.2

fruit tea

22.1

sP

ic

ga

rP

16.5

io

t

15.0

eb

it

fru

al

ur

N

at

N

at

N

at

candy

34.0

Pr

4.6

su

su

da

xi

i-o

A

9.2

ga

rF

nt

sF

sD

tic

io

it

s

fru

al

nt

ug

ar

D

nt

sD

da

xi

i-o

nt

A

pr

ob

le

m

He

sD

ar

ti

lln

es

sD

Ca

nc

To

er

D

ot

h

de

Na

ca

tu

y

ra

D

In

le

te

ne

sti

rg

na

y

lp

D

ro

bl

em

He

sF

ar

ti

lln

es

sF

Ca

nc

To

er

F

ot

h

de

N

ca

at

ur

y

F

al

In

en

te

er

sti

gy

na

F

lp

ro

bl

em

H

ea

P

rt

ill

ne

ss

P

Ca

nc

To

er

P

ot

h

de

Na

ca

tu

y

ra

P

le

ne

rg

y

P

sti

na

l

3.8

it

6.1

23.3

nt

sP

8.0

20.0

ru

7.3

eb

Pr

10

27.1

lf

11.8

da

10.0

20

20

sF

9.3

27.9

28.2

tic

34.1

nt

29.5

io

35.0

28.4

19.4

34.2

27.9

40

19.9

32.0

12.3

15.2

13.3

17.2

20.0

28.3

7.8

10.7

ur

a

13.0

17.9

xi

60

35.7

37.3

i-o

35.5

80

7.5

7.9

8.8

30

FIG. 2

Cumulative percentages of respondents who ranked products with a

particular positive influence on human health as interesting or most

interesting. Bars for the Dutch respondents are marked with a D, for the

French with an F, and for the Polish with a P.

I am extremely interested

FIG. 3

Level of consumer interest in products containing dried fruit with

certain functional ingredients. An asterisk denotes significant

differences between nationalities at P = 0.05. The insert in the top lefthand corner shows the outcomes of Duncans MRT test. Functional

ingredients marked with the same lower-case letter did not differ

significantly within one nationality at P 0.05.

In

te

*

Dutch respondents (n = 440)

French respondents (n = 230)

Polish respondents (n = 412)

40

Prebiotics

eb

50

Natural fruit sugars

ur

Cumulative percentage

60

Pr

Consumer interest in dried fruit as a carrier of functional

ingredients

All three nationalities agreed that they were highly

interested in dried fruit with anti-oxidant properties

(Figure 3). These findings may have a connection with

the high level of appreciation by consumers of products

that lower the risk of cancer because, in the statements

presented to respondents, anti-oxidants were mentioned

as ingredients which may decrease the risk of cancer. In

experiments conducted by Sosiska et al. (2006), 55% of

Polish and 49% of Belgian respondents admitted that

they did not know about the influence of anti-oxidants

on human health. However, Bech-Larsen et al. (2001)

argued that an elaborated claim can have a positive

effect on the acceptance of a functional ingredient which

is still unknown to consumers. Thus, high consumer

interest in dried fruit with anti-oxidants may have arisen

from the proper explanation of the influence of anti-

Anti-oxidants

% of respondents

Consumer interest in food products with a positive

influence on human health

Concerning products with a positive influence on

human health, Dutch and Polish respondents were highly

interested in products which could reduce the risk of

heart disease or cancer (Figure 2). Approx. 52% of these

respondents claimed that they were most (or only)

interested in food which could lower the risk of heart

disease. A high level of interest was expressed in

products that lowered the risk of cancer, this was

indicated by 45.9% of Polish consumers and 54.8% of

Dutch consumers. Although French consumers also

appreciated products which lowered the risk of heart

diseases or cancer, they ranked food which could prevent

intestinal problems more highly. This finding is consistent

with a study by Bech-Larsen et al. (2001), where the

majority of Danish, Finnish, and American consumers

preferred products which lowered the risk of heart

disease. Moreover, according to Cathro and Hilliam

(1993), heart disease was ranked highly by UK and

German respondents; but, in France, it was placed behind

stress and migraine. The high interest of French

respondents in products that prevented intestinal

problems may be due to an increase in marketing of

functional dairy products (Euromonitor, 2004).

87

cereals

muesli bars

cookies

FIG. 4

Consumer preferences towards certain forms of products containing

dried fruit. Columns for the Dutch respondents are marked with a D, for

the French with an F, and for the Polish with a P.

88

Dried fruit and its functional properties

indicate that respondents preferred those products in

which they ate dried fruit more often (Jesionkowska

et al., 2008). Products usually recognised as unhealthy

(e.g., candies, bars) could benefit from enrichment in a

functional ingredient.

In this study, a tendency was observed that consumers

appreciated candies and muesli bars with dried fruit and

with natural fruit sugars. It seems that this type of

product could benefit from adding dried fruit with

natural fruit sugars. Similarly, Bech-Larsen et al. (2001)

noticed that consumers do not increase the healthiness

of yoghurts and juices with functional ingredients

because these products are already perceived as being

healthy per se. In contrast, spreads could benefit from

functional enrichment, because this product is perceived

as inherently unhealthy.

CONCLUSIONS

1. All three nationalities agreed that they ate dried

fruit because it was a source of energy. Moreover, Dutch

respondents appreciated the presence of fibre most

highly, whereas Polish consumers ranked the content of

vitamins most highly.

2. Both Dutch and Polish respondents ranked products

which could lower the risks of cancer and heart disease

as the most interesting, while French consumers chose

products that could prevent intestinal problems.

3. It can be concluded that dried fruits may be

accepted as products with functional characteristics,

especially, when their anti-oxidant properties are

emphasised.

4. Cereals were pointed out to be the best product for

incorporating dried fruit with anti-oxidants or prebiotics

by approx. 33% of respondents.

The ISAFRUIT Project is funded by the European

Commission under Thematic Priority 5 Food Quality

and Safety of the 6th Framework Programme of RTD

(Contract No. FP6-FOOD-CT-2006-016279).

Disclaimer: Opinions expressed in this publication

may not be regarded as stating an official position of the

European Commission.

REFERENCES

ALZAMORA, S. M., SALVATORI, D., TAPIA, M. S., LOPEZ-MALO, A.,

WELTI-CHAMES, J. and FITO, P., (2005). Novel functional foods

from vegetable matrices impregnated with biologically active

compounds. Journal of Food Engineering, 67, 205214.

BECH-LARSEN, T., GRUNERT, K. G. and POULSEN, J. B. (2001). The

Acceptance of Functional Foods in Denmark, Finland and the

United States. MAPP Working Paper 73. The Aarhus School of

Business, Aarhus, Denmark. 125.

CATHRO, J. S. and HILLIAM, M. A. (1993). Future Opportunities for

Functional and Healthy Foods in Europe. An In-depth

Consumer and Market Analysis. Leatherhead Food Research

Association Special Report, Leatherhead, Surrey, UK. 203 pp.

EUROMONITOR (2004). The World Market for Functional Food and

Beverages. 1 January 2004. http://www.gmid.euromonitor.com.

EC (2006). Regulation No. 1924/2006 of the European Parliament

and of the Council of the European Union of 20 December

2006 on nutrition and health claims made on foods. Official

Journal of the European Union, L 12, 318.

FITO, P., CHIRALT, A., BARAT, J. M., MARTINEZ-MONZO, J. and

MARTINEZ-NAVARETTE, N. (2001). Vacuum impregnation to

development of new dehydrated products. Journal of Food

Engineering, 49, 297302.

HILLIAM, M. (1998). The market for functional foods. Dairy Journal,

8, 349353.

JESIONKOWSKA, K., KONOPACKA, D., POCHARSKI, W., SIJTSEMA, S.

and ZIMMERMANN, K. (2007). What do Polish and Dutch consumers think about dried fruit and products with them

Creative group discussions as a means of recognition

consumers perceptions. Polish Journal of Natural Science,

Supplement No. 4, 169175.

JESIONKOWSKA, K., SIJTSEMA, S., KONOPACKA, D., SYMONEAUX, R.

and POCHARSKI, W. (2008). Preferences and consumption of

dried fruit and dried fruit products among Dutch, French and

Polish consumers. Journal of Ornamental Plant Research, XVI,

275284.

JONAS, S. M. and BECKMANN, S. C. (1998). Functional Foods:

Consumer Perceptions in Denmark and England.Working Paper

No 55. The Aarhus School of Business, Aarhus, Denmark. 134.

MENRAD, K. (2003). Market and marketing of functional food in

Europe. Journal of Food Engineering, 56, 181188.

POULSEN, J. B. (1999). Danish Consumer Attitudes Towards

Functional Foods. MAPP Working Paper No 62.The Aarhus

School of Business, Aarhus, Denmark, 144.

SCHAAFSMA, G. and KOK, J. F. (2005). Nutritional aspects of food

innovations: a focus on functional foods. In: Innovation in

Agri-Food Systems. (Jongen, W. M. F. and Meulenberg, M. T G.,

Eds.). Wageningen Academic Publishers, Wageningen, The

Netherlands. 207220.

.

SOSIN SKA, E., TERLICKA, K. and KRYGIER, K. (2006). Zywno

funkcjonalna w opinii polskich i belgijskich konsumentw.

Przemys Spoywczy, 10, 4952. (In Polish).

STACEWICZ-SAPUNTZAKIS, M., BOWEN, P. E., HUSSAIN, E. A.,

DAMAYANTI-WOOD, B. I. and FARNSWORTH, N. R.

(2001).Chemical composition and potential health effects of

prunes; a functional food? Critical Reviews in Food Science and

Nutrition, 41, 251286.

TURNER, N. J. (1997). Food Plants of Interior First Peoples. UBC

Press, Vancouver, BC, Canada. 244 pp.

VAN KLEEF, E., VAN TRIJP, H. C. M. and LUNING, P. (2002).

Functional foods: Health-claim food product compatibility and

the impact of health claim framing on consumer evaluation.

Appetite, 44, 229308.

VAN KLEEF, E., VAN TRIJP, H. C. M., LUNING, P. and JONGEN, W. M.

F. (2005). Consumer-oriented functional food development:

How well do functional disciplines reflect the voice of the

consumer? Trends in Food Science and Technology, 13,

93101.

VAN TRIJP, H. C. M. and STEENKAMP, J. E. B. M. (2005).

Consumer-oriented new product development: principles and

practice. In: Innovation in Agri-Food Systems. (Jongen, W. M. F.

and Meulenberg, M. T G., Eds.). Wageningen Academic

Publishers, Wageningen, The Netherlands. 87124.

WANSINK, B., WESTGREN, R. E. and CHENEY, M. M. (2005).

Hierarchy of nutritional knowledge that relates to the

consumption of a functional food. Nutrition, 21, 264268.

You might also like

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Slimming Smoothies Salads For SummerDocument60 pagesSlimming Smoothies Salads For SummerArte DiverNo ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Food Safety Culture in Nigeria - Pathway To Behavioural FSMS Development in Nigerian Food IndustryDocument6 pagesFood Safety Culture in Nigeria - Pathway To Behavioural FSMS Development in Nigerian Food IndustryAdeniji Adeola StephenNo ratings yet

- FajitaDocument3 pagesFajitaDanNo ratings yet

- Industrial Crops and Products: Benita González, Hermine Vogel, Iván Razmilic, Evelyn WolframDocument8 pagesIndustrial Crops and Products: Benita González, Hermine Vogel, Iván Razmilic, Evelyn WolframOlivia Tapia LagunaNo ratings yet

- Revisión Del Simposio MILKDocument12 pagesRevisión Del Simposio MILKOlivia Tapia LagunaNo ratings yet

- Digital 2020 April Global Statshot Report Key InsightsDocument132 pagesDigital 2020 April Global Statshot Report Key InsightsOlivia Tapia LagunaNo ratings yet

- Yang 2000Document7 pagesYang 2000Olivia Tapia LagunaNo ratings yet

- Monitoring Autocorrelated Processes Using Variable Sampling Schemes at Fixed-TimesDocument15 pagesMonitoring Autocorrelated Processes Using Variable Sampling Schemes at Fixed-TimesOlivia Tapia LagunaNo ratings yet

- Structural Change and Economic Dynamics: Xiaoyong Dai, Zao SunDocument9 pagesStructural Change and Economic Dynamics: Xiaoyong Dai, Zao SunOlivia Tapia LagunaNo ratings yet

- Iler Di 2014Document8 pagesIler Di 2014Olivia Tapia LagunaNo ratings yet

- 10 1016@j Tibtech 2013 09 003 PDFDocument10 pages10 1016@j Tibtech 2013 09 003 PDFOlivia Tapia LagunaNo ratings yet

- A Carga Mundial de Morbilidad Atribuible Al Bajo Consumo de Frutas y VerdurasDocument9 pagesA Carga Mundial de Morbilidad Atribuible Al Bajo Consumo de Frutas y VerdurasOlivia Tapia LagunaNo ratings yet

- Fruta SsDocument106 pagesFruta SsOlivia Tapia LagunaNo ratings yet

- 10 1016@j Tibtech 2013 09 003Document6 pages10 1016@j Tibtech 2013 09 003Olivia Tapia LagunaNo ratings yet

- PrunusDocument17 pagesPrunusOlivia Tapia LagunaNo ratings yet

- Actitudes Relacionados Con La Salud Como Base para La Segmentación de Los Consumidores Europeos de PescadoDocument8 pagesActitudes Relacionados Con La Salud Como Base para La Segmentación de Los Consumidores Europeos de PescadoOlivia Tapia LagunaNo ratings yet

- Actitudes de Los Consumidores Hacia ManzanaDocument9 pagesActitudes de Los Consumidores Hacia ManzanaOlivia Tapia LagunaNo ratings yet

- Las Mujeres, Los Hombres y Los AlimentosDocument27 pagesLas Mujeres, Los Hombres y Los AlimentosOlivia Tapia LagunaNo ratings yet

- Características Físico-Químicas de AlbaricoqueDocument7 pagesCaracterísticas Físico-Químicas de AlbaricoqueOlivia Tapia LagunaNo ratings yet

- La Publicidad de La Salud para Promover El ConsumoDocument17 pagesLa Publicidad de La Salud para Promover El ConsumoOlivia Tapia LagunaNo ratings yet

- El Desarrollo de Los Frutos Secos Con Probióticos Enriquecido Por Impregnación Al VacíoDocument5 pagesEl Desarrollo de Los Frutos Secos Con Probióticos Enriquecido Por Impregnación Al VacíoOlivia Tapia LagunaNo ratings yet

- Stability of Market SegmentationDocument9 pagesStability of Market SegmentationOlivia Tapia LagunaNo ratings yet

- Utilization of Food Processing By-Products As Dietary, Functional, and Novel Fiber: A ReviewDocument16 pagesUtilization of Food Processing By-Products As Dietary, Functional, and Novel Fiber: A ReviewKhaled Abu-AlruzNo ratings yet

- Dennys MenuDocument12 pagesDennys MenuAyah Al-AnaniNo ratings yet

- Pas Inggriis SMT Ganjil 9Document9 pagesPas Inggriis SMT Ganjil 9Almah WiladatikaNo ratings yet

- UntitledDocument4 pagesUntitledEureka De diosNo ratings yet

- Goan CuisneDocument3 pagesGoan CuisneSunil KumarNo ratings yet

- AllAboutFeed - Formulating Fish Feed Using Earthworms As A Protein SourceDocument5 pagesAllAboutFeed - Formulating Fish Feed Using Earthworms As A Protein Sourcemkfe2005No ratings yet

- Empty Stomach (Morning) : Protein 20GDocument2 pagesEmpty Stomach (Morning) : Protein 20GskpakaleNo ratings yet

- Case Study: DTF 10102: Food SanitationDocument5 pagesCase Study: DTF 10102: Food Sanitationyuyu dayuNo ratings yet

- You Are What You EatDocument31 pagesYou Are What You Eatapi-356444313No ratings yet

- 1 Quarter Appetizer: RecipesDocument4 pages1 Quarter Appetizer: RecipesannanbNo ratings yet

- Dagupan's Annual Bangus Festival Showcases Pangasinan's Finest MilkfishDocument9 pagesDagupan's Annual Bangus Festival Showcases Pangasinan's Finest MilkfishAnn SANo ratings yet

- Impact of SchoolfeedingDocument70 pagesImpact of SchoolfeedinglamaNo ratings yet

- TMC Dialogue Ed.Document8 pagesTMC Dialogue Ed.Pnk Telok KemangNo ratings yet

- FSHN 450 Resume Draft EditedDocument1 pageFSHN 450 Resume Draft Editedapi-298039380No ratings yet

- Acceptability of Citrus Maxima (Pomelo)Document19 pagesAcceptability of Citrus Maxima (Pomelo)mesiassabrina2008No ratings yet

- PREPARE SPONGE AND CAKES - Baking GuideDocument40 pagesPREPARE SPONGE AND CAKES - Baking Guidemahalia caraanNo ratings yet

- Copper ChimneyDocument18 pagesCopper ChimneySP PRANAYNo ratings yet

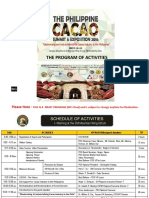

- Philippine Cacao Summit - Program As of May 18 2016Document8 pagesPhilippine Cacao Summit - Program As of May 18 2016Lorna DietzNo ratings yet

- FNB Module 1Document44 pagesFNB Module 1Christian BaylomoNo ratings yet

- Traditional Food of SabahDocument13 pagesTraditional Food of Sabahrex2690No ratings yet

- Cornish PastyDocument1 pageCornish PastyPatricia BuddNo ratings yet

- Research SourcesDocument6 pagesResearch Sourcesapi-318035889No ratings yet

- Extruded Chia Corn Meal PuffDocument5 pagesExtruded Chia Corn Meal Puffmohd shariqueNo ratings yet

- Customer Satisfaction Analysis of 7up in BangladeshDocument51 pagesCustomer Satisfaction Analysis of 7up in BangladeshMd Shams0% (2)

- German MPs push for higher meat tax to curb emissionsDocument2 pagesGerman MPs push for higher meat tax to curb emissionsAlec LoaiNo ratings yet

- Crawford Market Vegetable and Spice PricesDocument11 pagesCrawford Market Vegetable and Spice PricesKets ChNo ratings yet

- Farmer Business School (FBS)Document2 pagesFarmer Business School (FBS)mdnhllNo ratings yet