Professional Documents

Culture Documents

CHF Pathophys Paper

Uploaded by

Sarah SCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

CHF Pathophys Paper

Uploaded by

Sarah SCopyright:

Available Formats

Running head: CONGESTIVE HEART FAILURE

Congestive Heart Failure

S. Schneider

**** **** College

Running head: CONGESTIVE HEART FAILURE

Congestive Heart Failure

Definition

Congestive heart failure (CHF), formerly referring to just left sided heart failure, is a common,

yet complex, clinical disorder that can result from any functional or structural cardiac disorder that

impairs the ventricles ability to fill with or eject blood.(Figueroa, M. and Peters, J., 2006, pg. 402).

Congestive heart failure may be acute or chronic and ranges from mild to severe in nature. There are

two sub-types: systolic and diastolic. Systolic heart failure results when the heart has insufficient

strength to contract forcefully enough to eject adequate amounts of blood into the circulation. Diastolic

heart failure occurs when the left ventricle cannot relax adequately during diastole (relaxation phase)

which prevents the ventricle from filling with sufficient blood to ensure normal cardiac output and

tissue perfusion.(Ignatavicius, D., and Workman, L., 2013, pg. 715). Within this paper we will be

focusing in systolic heart failure.

Risk factors

There are major unmodifiable and modifiable risk factors to congestive heart failure. The major

unmodifiable risk factors include age (over 65), family history, congenital heart defects, valvular heart

disease, past myocardial infarction (heart attack), irregular heart rhythms, and coronary artery disease.

(Mayo Clinic Staff, 2015). The major modifiable risk factors include sedentary lifestyle, obesity,

uncontrolled diabetes mellitus, uncontrolled hypertension, poor diet and nutrition, alcohol use, and

tobacco use (smoking, chewing, etc.) (American Heart Association (AHA), 2015).

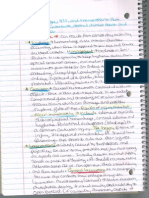

Pathophysiology

Congestive heart failure (CHF) is both an acute and chronic disorder that develops when the heart is

unable to maintain adequate ejection of blood and perfusion of organs. Cardiac dysfunction causes a

drop in cardiac output which leads to the activation of several neurohormonal pathways. (Gorbunova,

S., n.d.). As noted by Hobbs, R., & Boyle, A. (2014, March 1), in systolic dysfunction the body

Running head: CONGESTIVE HEART FAILURE

activates the sympathetic nervous system (through neurohormonal tracts) that increases heart rate and

strength of contractions, which results in vasoconstriction that stimulates secretion of renin from the

juxtaglomerular apparatus of the kidney due to loss of perfusion. Stimulation of the renin-angiotensin

system as a result of increased sympathetic stimulation and decreased renal perfusion results in further

vasoconstriction, sodium and water retention, and release of aldosterone. An increased aldosterone

level, in turn, leads to sodium and water retention, and other complications. Preload and afterload

increase as sodium and water are retained. Angiotensin II furnishes ventricular changes resulting in

advancing myocyte contractile dysfunction. Natriuretic peptides are neurohormones that work to boost

vasodilation and diuresis through sodium excretion in the kidney tubules. Brain naturietic peptide

(BNP) is produced and excreted by the ventricles when the client has fluid volume excess from CHF.

(Ignatavicus, D. & Workman, L., 2013). Another compensatory mechanism is the enlargement of the

cardiac muscle, with or without the increase in ventricular size. These walls thicken to increase the

force of contractions but may hypertrophy faster than collateral circulation can supply adequate blood

supply. (Ignatavicius, D., & Workman, L., 2013).

Complications

The complications of CHF arise from the decrease in tissue perfusion. This decrease in

perfusion leads to serious tissue damage and in turn congestion of the circulatory system. Such

complications that can arise are: kidney damage/failure, heart valve problems, and liver damage. The

kidney damage and/or failure arises from the decrease in blood flow which may require dialysis for

treatment. Heart valve problems arise from the damage sustained from high pressure or from the

enlargement of the heart muscle. Liver damage is done via the fluid backup which leads to scarring of

the liver making it hard for the liver to function properly. (Mayo Clinic, 2015 August 18).

Running head: CONGESTIVE HEART FAILURE

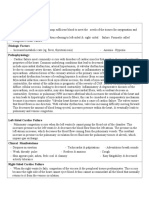

Table 1

Client to Textbook Comparison

Textbook

Client

Clinical Manifestations

1. Cough

2. Breathlessness

3. Weakness

4. Dizziness

5. Acites

6. Peripheral Edema

7. JVD

8. Cardiomegaly

9. Decreased Mentation

10. Decreased SpO2

11. Reduced Kidney Function

12. Chest Pain

13. Weight Gain

1. None upon assessment

2. Exertional related to pain from

RLE infection

3. Present, unable to hold self

over while turning in bed.

Weak to moderated grips and

plantar/dorsifelxion.

4. None noted upon assessment

5. None noted upon assessment

Abdominal obesity.

6. +2-3 pitting edema on

bilateral lower extremities,

and +1 on bilateral upper

extremities.

7. None upon assessment or

admission

8. None noted upon admission

9. Some

forgetfulness/disorientation at

times. Re-orientated easily.

Noted that opioid pain

medications have caused this

in the past.

10. Upon admission O2 Sat was

in high 90s but currently in

low 90s.

11. GFR 66/57

12. None upon assessment or

admission

13. Upon admission had gained

2-4 lbs; diuresing with Lasix.

Current weight 80.28 kg.

Diagnostic Labs, Tests,

Procedures

1. History and Physical

1. Past smoker history for 30

2. Urinalysis

years (quit in 2006), HTN,

3. Troponin

COPD, cataracts (surgeries in

4. BNP

08 and 13) worked as a sales

5. Serum Electrolytes

manager at a department store

6. Arterial Blood Gases

and homemaker.

7. Hemoglobin and Hematocrit 2. Clear, straw colored, voided

8. BUN and Creatinine & Protein 25 mL, Sp. Gravity 1.004

9. Chest X-Ray

(low), pH 5.0 - 9/14/15.

10. Echocardiogram

3. <0.04 - 9/15/15

Running head: CONGESTIVE HEART FAILURE

H&P

Medical Management

11. EKG

12. MUGA

4. 216 9/14/15

5. K+ = 3.8, Na+ = 137,

CO2 = 26

6. Not ordered

7. HgB: 10.3, Hct: 31.2

9/15/15

8. Protein: 3.9 6/5/15, BUN

and Creatinine not ordered

9. Cardiac silhouette and

pulmonary vasculature show

mildly prominent congestion,

increased opacity in bases

5/19/15

10. Not ordered

11. Normal Sinus 9/14/15

12. Not ordered

1. Past Medical History

2. Home Meds

3. Vitals and Pain

4. Respiratory Status

5. Family Hx.

1. Hx. COPD, essential

hypertension, cataracts

(surgeries in 08 and 13),

obesity, hyperlipidemia,

anemia and depression.

2. ASA 81 mg qd, Celexa 20 mg

qd, ferrous sulfate 325 mg (65

mg Fe) qd, Hydralazine 50 mg

bid, Imdur 30 mg qd, Cozaar

50 mg qd, Multivitamin qd,

Simvastatin 20 mg qPM,

Spiriva inhal 18 mcg qd,

Vitamin B-12 500 mcg qd.

3. Bp: 149/48 (0755 9/15/15)

150/49 (1200 9/15/15); Temp:

98.2 (0755 9/15/15) 98.1

(1200 9/15/15); Pulse: 78

(0755 9/15/15) 74 (1200

9/15/15); SpO2: 93% RA

(0755 9/15/15) 94% RA

(1200 9/15/15); Pain: 0 (0755

9/15/15) 10/10 (1200

9/15/15).

4. Room air, unlabored

breathing, equal chest

expansion, lungs CTA.

5. Not on file

1. Drug Therapy

a. Beta-Blockers

1. Meds

a. Not ordered

Running head: CONGESTIVE HEART FAILURE

b. ACE-inhibitors

c. Angiotensin Receptor

Blockers

d. Hydralazine and Nitrates

e. Aldosterone agonists

f. Diuretics

g. Digoxin

h. Heparin

2. CPAP

3. Cardiac Resynchronization

Therapy

4. Investigative Gene Therapy

5. Oxygen Therapy

6. Diet Therapy

7. Fluid Restriction

8. Strict I&O

b. Not ordered

c. Cozaar 50 mg qd

d. Hydralazine 50 mg bid,

Imdur 30 mg qd.

e. Not ordered

f. Lasix 40 mg qd

g. Not ordered

h. Heparin 5,000 units q 8hr

for DVT prevention

2. Not indicated for pt.

3. Not indicated for pt.

4. Not indicated for pt.

5. Room air

6. Cardiac, Low Na diet.

7. Not ordered

8. Not ordered

Surgical Management

1. Heart Transplant

2. Ventricular Assist Devices

3. Partial Left Ventriculectomy

4. Endoventricular Patch

5. Acorn Cardiac Support Device

6. Myosplint

1. Not indicated for pt.

2. Not indicated for pt.

3. Not indicated for pt.

4. Not indicated for pt.

5. Not indicated for pt.

6. Not indicated for pt.

Nursing Management

1. Administer Meds as Ordered

2. Health Teaching and

Promotion

3. Assess Patient for Clinical

Manifestations

4. Monitor Vital Signs

5. Monitoring I&O and Weight

6. Monitoring Lab Studies

7. Maintaining HOB Elevation

1. RN assigned to patient

administered medications as

ordered.

2. Taught client: how to use the

incentive spirometer and to

breathe in deeply and slowly

to increase the amount of

oxygen the body receives,

choosing healthy choices for

food, and importance of doing

some physical activity (even if

it is just ROM exercises).

3. Completed physical

assessment on patient and

noted no other signs of

congestive heart failure (CHF)

except for edema, and some

weakness.

4. Monitored vital signs in the

morning and afternoon.

5. Charted when patient voided

urine. Check chart for updated

weight.

Running head: CONGESTIVE HEART FAILURE

6. Looked up lab studies for

patient. 0500 labs were

resulted, however no

additional labs were

ordered/resulted.

7. Maintained HOB at 30-45

degrees unless patient was

eating then at 90 degrees and

when placing patient on

bedpan and taking patient off

bedpan lowered head of bed.

(Winkelman, C., 2013, pp. 351-355) (Ignatavicius, D., & Workman, L., 2013, pp. 751-754)

Contributing Factors Relating to the Pathology

This is a 85 year old female that also suffers from COPD, anemia, obesity, hyperlipidemia,

essential hypertension and depression. She is currently 28.6 pounds overweight for her age and height.

While at the hospital she does not have much of an appetite. She does not exercise regularly due to age,

weakness, COPD, and going to cancer appointments with her husband. She complains of right lower

extremity pain. She is also a past pack a day smoker for 30 years and quit in 2006. Upon review of this

patient's health history, the contributing factors leading to her development of CHF include obesity,

hyperlipidemia, COPD, hypertension, sedentary lifestyle, age, and previous smoking history.

Running head: CONGESTIVE HEART FAILURE

References

American Heart Association (AHA). (2015, July 29). Causes and Risks for Heart Failure. Retrieved

September 20, 2015, from

http://www.heart.org/HEARTORG/Conditions/HeartFailure/UnderstandYourRiskforHeart

Failure/Causes-and-Risks-for-Heart-Failure_UCM_002046_Article.jsp

Hobbs, R., & Boyle, A. (2014, March 1). Heart Failure. Retrieved September 20, 2015, from

http://www.clevelandclinicmeded.com/medicalpubs/diseasemanagement/cardiology/heartfailure/Default.htm

Figueroa, M., & Peters, J. (2006). Congestive Heart Failure: Diagnosis, Pathophysiology, Therapy, and

Implications for Respiratory Care. Respiratory Care, 51(4), 402-412. Retrieved September 14,

2015, from http://www.rcjournal.com/contents/04.06/04.06.0403.pdf

Gorbunova, S. (n.d.). What is Heart Failure? Retrieved September 18, 2015, from

http://www.queri.research.va.gov/chf/products/nurse_education/What-is-Heart-Failure.pdf

Ignatavicius, D., & Workman, L. (2013). Medical-surgical nursing: Patient-centered collaborative

care (7th ed., pp. 747-758). St. Louis, MO: Saunders/Elsevier.

Mayo Clinic. (2015, August 18). Heart failure (R. Mankad, Ed.). Retrieved September 19, 2015, from

http://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/heart-failure/basics/complications/con20029801

Mayo Clinic. (2015, August 18). Heart failure (R. Mankad, Ed.). Retrieved September 16, 2015, from

http://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/heart-failure/basics/risk-factors/con-20029801

Winkelman, C. (2013). Clinical companion, Ignatavicius Workman, Medical-surgical nursing: Patientcentered collaborative care. (7th ed., pp. 349-355). St. Louis, MO: Elsevier Saunders.

You might also like

- Chronic Heart FailureDocument11 pagesChronic Heart FailurelaydyNo ratings yet

- Heart Failure in ChildrenDocument47 pagesHeart Failure in ChildrenDr.P.NatarajanNo ratings yet

- NCM 106 Acute Biologic CrisisDocument142 pagesNCM 106 Acute Biologic CrisisEllamae Chua88% (8)

- Pharmacology II Sovan Sarkar 186012111012Document14 pagesPharmacology II Sovan Sarkar 186012111012Sovan SarkarNo ratings yet

- Understanding Major Chronic Illnesses of Older AdultsDocument21 pagesUnderstanding Major Chronic Illnesses of Older AdultsSteffiNo ratings yet

- Heart Failure IntroductionDocument12 pagesHeart Failure IntroductionJasper VictoryNo ratings yet

- Lec 3 Heart FailureDocument25 pagesLec 3 Heart FailureDelete AccountNo ratings yet

- PEMICU 4 KV CynthiaDocument55 pagesPEMICU 4 KV CynthiaEko SiswantoNo ratings yet

- Tugass Paper BryanDocument10 pagesTugass Paper BryanMauritius BryanNo ratings yet

- CHFDocument61 pagesCHFAngeline Lareza-Reyna VillasorNo ratings yet

- Cardiac FailureDocument63 pagesCardiac FailureNina OaipNo ratings yet

- NURSING CARE PLAN for 8yo Male with CHDDocument5 pagesNURSING CARE PLAN for 8yo Male with CHDDonna Co IgNo ratings yet

- Cardiac Case Study on Coronary Artery Disease RiskDocument4 pagesCardiac Case Study on Coronary Artery Disease RiskElizabeth SpokoinyNo ratings yet

- Gerontic Nursing: Elderly With Hypertension: Arranged Group 11: Suci Aulia (1714201042)Document15 pagesGerontic Nursing: Elderly With Hypertension: Arranged Group 11: Suci Aulia (1714201042)anisaNo ratings yet

- Case Study 8 9 10 11Document12 pagesCase Study 8 9 10 11jovan teopizNo ratings yet

- Heart Failure (Recovered)Document43 pagesHeart Failure (Recovered)Binal Joshi100% (1)

- EndocarditisDocument6 pagesEndocarditisMerry Joy DeliñaNo ratings yet

- PBL 3 FixDocument37 pagesPBL 3 FixYusril DjibranNo ratings yet

- Heart FailureDocument8 pagesHeart FailureSophia MarieNo ratings yet

- Cardiomyopathy Self StudyDocument3 pagesCardiomyopathy Self StudySolomon Seth SallforsNo ratings yet

- Nutrition Case StudyDocument17 pagesNutrition Case Studymacedon14100% (18)

- CHF PBLDocument3 pagesCHF PBLqtiefyNo ratings yet

- Congestive Heart Failure (CHF) : BY Miss. S. D. Ajetrao Assistant Professor ADCDP, AshtaDocument16 pagesCongestive Heart Failure (CHF) : BY Miss. S. D. Ajetrao Assistant Professor ADCDP, AshtaChandraprakash JadhavNo ratings yet

- Nursing Care Process Case StudyDocument6 pagesNursing Care Process Case StudyEunice RosalesNo ratings yet

- Observation Report - Hemodialysis - Kit P. RoaquinDocument15 pagesObservation Report - Hemodialysis - Kit P. Roaquineljhayar_18No ratings yet

- Congestive Heart FailureDocument17 pagesCongestive Heart FailureLyana StarkNo ratings yet

- Nursing Study GuideDocument21 pagesNursing Study GuideYanahNo ratings yet

- Deborah Mukendenge Mujinga Nurs201Document6 pagesDeborah Mukendenge Mujinga Nurs201Lois MpangaNo ratings yet

- High output heart failure: a reviewDocument7 pagesHigh output heart failure: a reviewChanvira Aria CandrayanaNo ratings yet

- MR Kumar Case Study: Student Name Department, University Course Name Professor NameDocument7 pagesMR Kumar Case Study: Student Name Department, University Course Name Professor NameVincent Karimi GichimuNo ratings yet

- Literature Review On Congestive Heart FailureDocument4 pagesLiterature Review On Congestive Heart Failurefihynakalej2100% (1)

- Kel 7Document13 pagesKel 7hananNo ratings yet

- Tgs Bhs InggrisDocument22 pagesTgs Bhs InggrisHarda DedaliNo ratings yet

- Latar BelakangDocument25 pagesLatar BelakangririnagustinNo ratings yet

- Clinical Symptoms Due To Fluid CongestionDocument5 pagesClinical Symptoms Due To Fluid CongestionBrandedlovers OnlineshopNo ratings yet

- Cardiogenic Shock NDDocument8 pagesCardiogenic Shock NDLizbet CLNo ratings yet

- Hypertension: Pathophysiology, Diagnostic Test, Medical Management, and Nursing Care PlanDocument12 pagesHypertension: Pathophysiology, Diagnostic Test, Medical Management, and Nursing Care PlanMaulidyaFadilahNo ratings yet

- Medical Nutrition Therapy A Case Study Approach 5th Edition Nelms Solutions ManualDocument8 pagesMedical Nutrition Therapy A Case Study Approach 5th Edition Nelms Solutions Manualsophiechaurfqnz100% (31)

- Medical Nutrition Therapy A Case Study Approach 5Th Edition Nelms Solutions Manual Full Chapter PDFDocument29 pagesMedical Nutrition Therapy A Case Study Approach 5Th Edition Nelms Solutions Manual Full Chapter PDFStephanieMckayeqwr100% (7)

- Reflective Journaling 1Document12 pagesReflective Journaling 1Nosheen ShahNo ratings yet

- Heart Failure: Causes, Symptoms, and TreatmentDocument36 pagesHeart Failure: Causes, Symptoms, and TreatmentnathanNo ratings yet

- Fluid and Electrolytes for Nursing StudentsFrom EverandFluid and Electrolytes for Nursing StudentsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (12)

- Heart Failure: Definition and EpidemiologyDocument6 pagesHeart Failure: Definition and EpidemiologyIshwarya SivakumarNo ratings yet

- Case Study For Chronic Renal FailureDocument6 pagesCase Study For Chronic Renal FailureGabbii CincoNo ratings yet

- Heart Failure: Causes, Signs, TestsDocument6 pagesHeart Failure: Causes, Signs, Testsصفا رياض محمد /مسائيNo ratings yet

- Congestive Heart FailureDocument39 pagesCongestive Heart FailureEthiopia TekdemNo ratings yet

- Cardiac Failure & Myocardial Infarction GuideDocument6 pagesCardiac Failure & Myocardial Infarction GuideDaniel GeduquioNo ratings yet

- Angina Pectoris: Chest Pain Causes and TreatmentsDocument7 pagesAngina Pectoris: Chest Pain Causes and TreatmentsTruptilata SahooNo ratings yet

- Congestive Heart Failure: EtiologyDocument3 pagesCongestive Heart Failure: EtiologyJoshua VillarbaNo ratings yet

- Managing A Patient With Es RD 23Document3 pagesManaging A Patient With Es RD 23Undefined RegisterNo ratings yet

- EPP SEMESTER 6 Baru BNGTDocument8 pagesEPP SEMESTER 6 Baru BNGTLisa FitrianiNo ratings yet

- Understanding Hypertension: A Report on Causes, Symptoms and TreatmentDocument11 pagesUnderstanding Hypertension: A Report on Causes, Symptoms and TreatmentanggaraNo ratings yet

- Final Research PaperDocument8 pagesFinal Research Paperapi-301053941No ratings yet

- Congestive Heart FailureDocument14 pagesCongestive Heart FailureBella Trix PagdangananNo ratings yet

- Chapter 33 HypertensionDocument5 pagesChapter 33 HypertensiongytmbiuiNo ratings yet

- Case Analysis: Medical Surgical NursingDocument7 pagesCase Analysis: Medical Surgical NursingMaria ThereseNo ratings yet

- CHF Case OutputDocument3 pagesCHF Case OutputJethro Floyd QuintoNo ratings yet

- Assignment 3Document5 pagesAssignment 3api-577583685No ratings yet

- Nurs220 F and e Case Study Gfranklin220 Doc-2Document9 pagesNurs220 F and e Case Study Gfranklin220 Doc-2api-355433171No ratings yet

- Report About HypertensionDocument11 pagesReport About HypertensionZA IDNo ratings yet

- Sensory EOs Part 2Document12 pagesSensory EOs Part 2Sarah SNo ratings yet

- GP PresentationDocument11 pagesGP PresentationSarah SNo ratings yet

- NSG 222 Test 3 Part One EODocument7 pagesNSG 222 Test 3 Part One EOSarah SNo ratings yet

- N126 Student WorksheetDocument2 pagesN126 Student WorksheetSarah SNo ratings yet

- Pharmacology Alphabet AllDocument4 pagesPharmacology Alphabet Allsflower85No ratings yet

- Study Guide For DiasterDocument7 pagesStudy Guide For DiasterSarah SNo ratings yet

- Hints For Remembering Medication ClassificationsDocument2 pagesHints For Remembering Medication ClassificationsSarah SNo ratings yet

- Final Exam Review Sheet1 Mental Health NursingDocument30 pagesFinal Exam Review Sheet1 Mental Health NursingSarah S100% (5)

- Bumex Pharmacology Data SheetDocument1 pageBumex Pharmacology Data SheetSarah SNo ratings yet

- Clinical Organization Sheet for N126 PatientDocument1 pageClinical Organization Sheet for N126 PatientSarah S100% (1)

- Application of Theories NSG 221 Module 1.1Document20 pagesApplication of Theories NSG 221 Module 1.1Sarah SNo ratings yet

- IV Therapy ComplicationsDocument6 pagesIV Therapy ComplicationsSarah SNo ratings yet

- Cultural Presentation For Nursing SchoolDocument9 pagesCultural Presentation For Nursing SchoolSarah SNo ratings yet

- Fluid Balance NotesDocument4 pagesFluid Balance NotesSarah SNo ratings yet

- Fluid Balance Notes-1Document3 pagesFluid Balance Notes-1Sarah SNo ratings yet

- Fluid and Electrolytes PracticeDocument16 pagesFluid and Electrolytes PracticeSarah SNo ratings yet

- Fluid and Electrotlytes WorksheetDocument2 pagesFluid and Electrotlytes WorksheetSarah SNo ratings yet

- M7 Nutrition and HealthDocument2 pagesM7 Nutrition and HealthErykah Faith PerezNo ratings yet

- How and When To Be Your Own Doctor by Moser, IsabelDocument135 pagesHow and When To Be Your Own Doctor by Moser, IsabelGutenberg.org100% (2)

- Singapore Tops Global Average Peak Internet SpeedDocument7 pagesSingapore Tops Global Average Peak Internet Speedgusti annisaNo ratings yet

- Complications of Diabetes MellitusDocument147 pagesComplications of Diabetes MellitusNisrina SariNo ratings yet

- Nutritional TherapyDocument34 pagesNutritional TherapyArshi BatoolNo ratings yet

- Q & A (NCLEX) 2Document146 pagesQ & A (NCLEX) 2verzonicNo ratings yet

- Alpha Calc IdolDocument34 pagesAlpha Calc IdolSaroj Poudyal0% (1)

- Jelang Jelku D. SangmaDocument7 pagesJelang Jelku D. Sangmahaftamu GebreHiwotNo ratings yet

- Feed Enzymes Can Help Manage Price Volatility: FeedstuffsDocument3 pagesFeed Enzymes Can Help Manage Price Volatility: FeedstuffsAbtl EnzymesNo ratings yet

- Dietary Guidelines For IndiansDocument126 pagesDietary Guidelines For IndiansVivek PoojaryNo ratings yet

- SOP FinalDocument7 pagesSOP FinalsabaNo ratings yet

- Effect of Endurance Trainingg On Parameters of Aerobic FitnessDocument14 pagesEffect of Endurance Trainingg On Parameters of Aerobic FitnessClaudia LoughnaneNo ratings yet

- Luciano Passuello One Small Step Can Change Your Life FullDocument1 pageLuciano Passuello One Small Step Can Change Your Life FullSridhar ReddyNo ratings yet

- Pes Statements SamplesDocument19 pagesPes Statements SamplesJennie ManobanNo ratings yet

- Double Shaft Paddle MixerDocument4 pagesDouble Shaft Paddle MixerAntonio ReisNo ratings yet

- Super Immune System: Detoxification GuidelinesDocument6 pagesSuper Immune System: Detoxification GuidelinesRoxanaDucaNo ratings yet

- OCN Exam Flashcard Study System - OCN Test Practice Questions & Review For T-1Document1,255 pagesOCN Exam Flashcard Study System - OCN Test Practice Questions & Review For T-1NicoleNo ratings yet

- Ursolic Acid and Mechanisms of Actions On Adipose and Muscle Tissue A Systematic ReviewDocument12 pagesUrsolic Acid and Mechanisms of Actions On Adipose and Muscle Tissue A Systematic ReviewIgor BiggieNo ratings yet

- 5th Probiotics Prebiotics NewfoodDocument356 pages5th Probiotics Prebiotics NewfoodMichael HerreraNo ratings yet

- EMF SensitivityDocument25 pagesEMF SensitivitySundeeNo ratings yet

- HormonesBalance Superfoods Powerherbs Guides FINALDocument28 pagesHormonesBalance Superfoods Powerherbs Guides FINALAndrada Faur100% (1)

- Remaja - Skripsi. Universitas Sumatera Utara.: Daftar PustakaDocument5 pagesRemaja - Skripsi. Universitas Sumatera Utara.: Daftar PustakaimNo ratings yet

- Best 5-HTP Supplements of 2020: RatingDocument22 pagesBest 5-HTP Supplements of 2020: RatingTanjil TafsirNo ratings yet

- Faisal Coke 2Document85 pagesFaisal Coke 2Md FaisalNo ratings yet

- AnumwraDocument30 pagesAnumwratejasNo ratings yet

- Caring For Children 2: Babysitting BasicsDocument56 pagesCaring For Children 2: Babysitting BasicsmaureenlesNo ratings yet

- Omega-3 Benefits for All AgesDocument6 pagesOmega-3 Benefits for All Agescinefil70No ratings yet

- ResumeDocument2 pagesResumeapi-347141638No ratings yet

- Impact of Dietary Habits on Nutrition Status of StudentsDocument15 pagesImpact of Dietary Habits on Nutrition Status of StudentsEdcel BaragaNo ratings yet

- Open EPQ (7993) - Example A Star ProjectDocument58 pagesOpen EPQ (7993) - Example A Star Projectitssjustmariaxo4No ratings yet