Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Pediatric Emergency Department Thoracotomy (2015)

Uploaded by

Enzo_AEOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Pediatric Emergency Department Thoracotomy (2015)

Uploaded by

Enzo_AECopyright:

Available Formats

Journal of Pediatric Surgery 50 (2015) 177181

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

Journal of Pediatric Surgery

journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jpedsurg

Pediatric emergency department thoracotomy: A large case series and

systematic review

Casey J. Allen, Evan J. Valle, Chad M. Thorson, Anthony R. Hogan, Eduardo A. Perez, Nicholas Namias,

Tanya L. Zakrison, Holly L. Neville, Juan E. Sola

Division of Pediatric Surgery, DeWitt Daughtry Family Department of Surgery, University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, Miami, FL, USA

a r t i c l e

i n f o

Article history:

Received 5 October 2014

Accepted 6 October 2014

Key words:

Resuscitative thoracotomy

Children

Adolescents

Kids

a b s t r a c t

Background/purpose: The emergency department thoracotomy (EDT) is rarely utilized in children, and is thus

difcult to identify survival factors. We reviewed our experience and performed a systematic review of reports

of EDT in pediatric patients.

Methods: Patients age 18 years who received an EDT from 1991 to 2012 at our institution and all published case

series were reviewed. Data analyzed include age, sex, mechanism of injury (MOI), injury patterns, presence of

vital signs (VS) or signs of life (SOL) in the eld/ED, return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC), and survival.

Results: A total of 252 patients were analyzed. 84% were male. 51% sustained penetrating injuries, and median age

was 15 years. Upon arrival, 17% had VS, and 35% had SOL. After EDT, 30% experienced ROSC. The survival rate was

1.6% for blunt trauma, 10.2% for penetrating injuries, and 6.0% overall.

Conclusion: Survival of pediatric patients following EDT is comparable to recent analyses in adults. Children who

sustain blunt injury and are without SOL have been uniformly unsalvageable. Children who sustain penetrating

trauma and have SOL or are without SOL for a short time prior to arrival have been salvageable. There are no

reported EDT survivors less than 14 years of age following blunt injury.

2015 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

Trauma remains the leading cause of morbidity and mortality in

children and adolescents [1,2]. By recognizing this, care of the injured

child has improved with aggressive efforts to standardize treatment.

These efforts have inuenced the morbidity and mortality rates associated with pediatric trauma [35].

The standardization of care of the pediatric trauma patient, however,

has also created new problems that must be addressed. With improved

systems of transportation of injured children to major trauma centers,

patients who otherwise would have been pronounced dead at the

scene or at local hospitals are now arriving to referral centers for

evaluation and treatment. New decision-making criteria must be

established for resuscitative measures in the critically ill pediatric

trauma patient. In particular, the role of the emergency department

thoracotomy (EDT) has not been fully dened. Although there are

established guidelines for performing EDT in an adult, it has been difcult to identify trends and factors associated with survival in children

because it is rarely utilized in the pediatric patient.

To address this issue, we reviewed our experience at a level 1 trauma

center and report the largest analysis over the past 25 years. In conjunction, we performed a systematic review of all published reports

Corresponding author at: Division of Pediatric Surgery, DeWitt-Daughtry Family

Department of Surgery, University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, 1120 NW

14th Street, Suite 450K, Miami, FL 33136. Tel.: + 1 305 243 5072.

E-mail address: jsola@med.miami.edu (J.E. Sola).

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2014.10.042

0022-3468/ 2015 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

regarding pediatric EDT to help identify the factors associated with

morbidity and mortality.

1. Methods

With respect to our institution, we analyzed all pediatric patients

(age 18) who received an EDT from 1991 to 2012. Ryder Trauma

Center (RTC), located at the University of Miami/Jackson Memorial

Medical Center, is the only level 1 trauma center serving the 2.4 million

residents of Miami-Dade County, Florida. On average, 4300 trauma

patients per year are evaluated at RTC. Approximately, 10% of all

patients evaluated and treated at this center are injured children. Demographics obtained from our trauma registry included age, sex, mechanism of injury (MOI), and Injury Severity Score (ISS). We reviewed

patient records for the presence of vital signs (VS) and/or signs of life

(SOL) in the eld, time without VS in the eld, presence of VS or SOL

upon arrival, MOI, location of injuries, return of spontaneous circulation

(ROSC), survival, and neurological function of the survivors upon discharge. Presence of VS is dened as a palpable peripheral pulse upon arrival with a recorded initial systolic blood pressure and/or heart rate.

SOL is dened as breathing, pupillary reactivity, spontaneous movements, or mechanical cardiac activity. ROSC is resumption of sustained

perfusing cardiac activity after cardiac arrest. Signs of ROSC include a

palpable pulse or a measurable blood pressure as well as any breathing,

coughing, or movement. This study was approved by the Institutional

Review Board at the University of Miami Miller School Of Medicine.

178

C.J. Allen et al. / Journal of Pediatric Surgery 50 (2015) 177181

Table 1

Systematic review of the published case series regarding pediatric EDT along with data

from Ryder Trauma Center.

Powell et al. The American Surgeon, 1988

Beaver et al. J Pediatric Surgery, 1987

Rothenberg et al. J Trauma, 1989

Sheikh and Culbertson, J Trauma, 1993

Hofbauer et al. Resuscitation, 2011

Easter et al. Resuscitation, 2012

Boatright et al. JACS, 2013

Ryder Trauma Center, Miami, FL. 1991-2012

Survival

Blunt

Penetrating

Survival

1/8

0/15

1/47

0/15

0/10

0/13

0/9

0/7

2/124

4/11

0/2

2/36

1/8

1/1

3/16

0/0

2/54

13/128

5/19

0/17

3/83

1/23

1/11

3/29

0/9

2/61

15/252

Blunt versus penetrating, survival.

For our systematic review of the published data, we obtained all case

series regarding pediatric EDT and combined the data from those

reports with the data from our institution (Table 1) [613]. These

reports were obtained from a Medline search for all publications

regarding EDT in the pediatric population for the past 40 year using

the keywords thoracotomy, emergency, trauma, resuscitation,

pediatrics, and children. Bibliographies of relevant publications

were reviewed to identify reports that were not initially located with

the Medline search. Variables extracted from each report include demographics, MOI, injury location, presence of VS and/or SOL upon arrival,

ROSC, survival to discharge, and neurologic outcomes for survivors.

For publications that did not report certain variables, those cases were

systematically excluded when analyzing that missing variable.

Although each series differs in the specic data reported, the information obtained was pooled and analyzed using the variables and

outcomes reported by each series. To minimize bias, single case reports

are presented in the discussion but did not contribute to the systematic

analysis because a single case report does not represent a population.

Parametric data are reported as mean standard deviation and

nonparametric data are reported as median.

2. Results

At RTC, a total of 61 pediatric patients who had an EDT performed

were identied. Overall, our cohort was 90% were male, 88% sustained

penetrating injuries, median age was 16 years, and median ISS was 41

(Table 2). MOIs included gunshot wound (GSW) (74%), stab wound

(15%), and motor vehicle collision (8%). In the eld, 46% had initial VS

and 67% had SOL. Upon arrival, 25% had VS and 56% had SOL. Those

who lost VS in the eld were, on average, without VS for 15 16 minutes

prior to arrival. After EDT, 23 patients (38%) had ROSC. Of these, 21 expired (16 in OR, 4 in ED, 1 in ICU). Both survivors (15 and 16 years)

sustained penetrating injury (1 isolated to chest, 1 isolated to abdomen),

CNS

Chest/neck

Abdomen/pelvis

Extremity

Multiple

Survival

Blunt

Penetrating

Survival

0

3

0

0

4

0/7

0

29

7

3

15

2/54

0/0

1/32

1/7

0/3

0/19

2/61

Experience of Ryder Trauma Center 19912012.

had VS upon arrival, and were discharged with full neurological function.

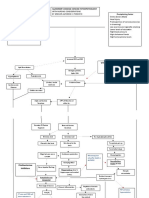

Injury locations and associated outcomes are depicted in Table 3. Fig. 1

displays the outcomes (ROSC and survival) according to MOI and

presence of VS/SOL.

Upon systematic review of the published data (including our data), a

total of 252 pediatric patients were analyzed (Table 4). Of these, 84%

were male, 51% sustained penetrating injury, and median age was

15 years. MOIs included GSW (34 %), stab wound (13%), MVC (11%),

PHBC (9%), and fall (3%). Patients most commonly presented with

major injury to the chest or neck (68%). Upon arrival, 17% had VS and

35% had SOL. After EDT, 30% experienced ROSC. An analysis of overall injury patterns and associated outcomes is depicted in Table 5. The survival rate for EDT was 1.6% in blunt trauma, 10.2% in penetrating injuries,

and 6.0% overall. Fig. 2 depicts the outcomes of the entire population

comprised by the systematic review, divided by blunt and penetrating

injury, with details regarding presence of SOL and/or VS upon arrival

within each subpopulation. The 2 reported survivors within the blunt

population both sustained multiple system injuries, whereas within

the penetrating population, the 13 survivors sustained injury to the

chest/neck (n = 9), abdomen/pelvis (n = 1), extremities (n = 1), or

multiple systems (n = 2). All reported survivors were discharged with

full neurological function.

When analyzing the younger pediatric population ( 12 years),

there were 37 reported EDT; representing 15% of the population. Of

these children, 25 (68%) sustained blunt injury, 15 (41%) arrived to the

ED with SOL, and 4 (11%) arrived with VS. Only 6 children (16%)

experienced ROSC, and only 1 ultimately survived. This patient, the

youngest reported survivor, was a 9 year old male who sustained a

stab wound to the heart [9]. The child presented to the ED physiologically

stable, but eventually developed hemorrhagic shock and went into

cardiac arrest [9].

The youngest survivor ever reported that sustained blunt force

trauma and required an EDT was a 14 year old male involved in an

MVC [10]. The patient arrived to the ED with VS but quickly deteriorated

[10]. This patient was not included in the systematic review as it is a

single case and not reported in a population series.

3. Discussion

Table 2

Demographics, MOI, outcomes (n = 61).

Male

Age (median)

Blunt

Penetrating

Mechanism of injury

Table 3

Systems injured; blunt versus penetrating, survival (n = 61).

MVC

PHBC

GSW

Stab

Assault

ISS (median)

VS in eld

SOL in eld

Time without vitals in eld (minutes)

VS ED

SOL ED

ROSC

Survival

Experience of Ryder Trauma Center 19912012.

90%

16

12%

88%

8%

2%

74%

15%

2%

41

46%

67%

15 16

25%

56%

38%

3.3%

EDT is considered the most aggressive form of resuscitation for

victims of trauma. Between 1965 and 1976, the use of EDT was reported

to improve survival following penetrating chest trauma [14]. Soon

thereafter, the utilization of EDT was reported as benecial in adult

patients with penetrating or blunt traumatic injuries [15,16].

The improved quality of pre-hospital emergency medical services

combined with the development of specialized pediatric trauma centers

has resulted in more critically injured children requiring evaluation on

the brink of death (in extremis). With recent reports showing the

detrimental outcomes associated with a prolonged pre-hospital period,

there has been a push for emergency medical services in urban environments to scoop and run rather than stay and play [17,18]. Many of

these patients in the past would have been pronounced dead at the

scene or at their community hospital emergency department. During

this development, the resuscitative thoracotomy was also added as an

extension to ATLS techniques [19]. Now after 30 years, we are able to

C.J. Allen et al. / Journal of Pediatric Surgery 50 (2015) 177181

179

Fig. 1. Outcomes according to MOI, presence of VS/SOL. Experience of Ryder Trauma Center 19912012.

systematically review the current literature with this relatively aggressive resuscitative measure in the pediatric population.

From our analysis, the mortality rates following EDT are similar

between adults and children. In 2011, the Western Trauma Association

(WTA) reviewed reports of the EDT in all populations. Their review

showed a survival rate of 11.2% following penetrating injury and 1.6%

following blunt trauma [20]. This is close comparison to our results

showing a pediatric survival rate of 10.2 and 1.6% in penetrating and

blunt injuries, respectively. Based upon their review that showed

these early similarities, WTA recommended performing an EDT in all

children under the same guidelines as that for adults [21]. Although

our outcomes appear consistent with those reported by the WTA, our

report shows a survival discrepancy between age groups within the

pediatric population. For example, of all children less than the age of

13 years, only 1 survivor has been reported [9]. Also, there have been

no reports of a survivor less than the age of 14 years who sustained

blunt force trauma and required an EDT. In contrast to the adult population, all reported blunt pediatric survivors had at least SOL upon arrival.

Within the penetrating trauma group, the survivors were also generally

older with a median age of 17 years.

There appears to be an age when a child acts physiologically similar

to an adult. Why are there no reports of blunt survivors less than the age

of 14 years? One likely explanation is that there has not been sufcient

accumulated experience with the younger pediatric population to observe the ~2% survivability. Physiologically, however, younger pediatric

Table 4

Demographics, MOI, outcomes (N = 252).

Age (median)

Male

Blunt

Penetrating

MOI

SOL ED

VS ED

ROSC

Survival

Systematic review of published reports.

MVC

PHBC

Fall

GSW

Stab

Assault

Crush

15

84%

49%

51%

11%

9%

3%

34%

13%

1%

1%

35%

17%

30%

6.0%

patients have proportionately larger cranial, thoracic and abdominal

organs, and are without a mature skeletal system, thus making them

more vulnerable to severe injury from traumatic forces. Theoretically,

because children have an increased physiologic reserve when compared

to that of an adult [22], an injury that completely overwhelms their

compensatory system is almost certainly non-survivable. Regardless,

even if all EDTs were performed under a uniform set of guidelines, it

appears this procedure is being over-performed in the pediatric population. Only 35% of all reported pediatric patients arrived with SOL.

Although the current 2011 WTA guidelines recommend an EDT after a

short time without SOL (15 minutes penetrating, 10 minutes blunt),

the guidelines in place during which the reports in this systematic

review were published recommended performing an EDT in a blunt

trauma patient only when SOL were present [23]. It was assumed any

patient who sustained blunt force trauma and arrived without SOL

was dead and no intervention should be performed. Yet it appears the

majority of pediatric EDTs for blunt trauma over the past 30 years

have been performed in the absence of SOL.

The over-performance of EDT was likely because of the lack of

known survival factors and perhaps an overly aggressive approach

when faced with a potential pediatric mortality. Anecdotal reports of

successful heroic resuscitation in children may have fostered the idea

that younger patients better tolerate the physiologic stresses of lifethreatening injuries and have improved functional outcomes [16,24].

Our conclusions oppose this theory.

There is growing interest in the use of a resuscitative endovascular

balloon occlusion of the aorta (REBOA) to control hemorrhagic shock

in trauma patients. To our knowledge, the REBOA remains a new and

still controversial tool. There are limited reports regarding its use in

trauma patients. Recently, Brenner et al. tested the technical feasibility

Table 5

Systems injured; overall, blunt versus penetrating, survival.

CNS

Chest/neck

Abdomen

Extremity

Multiple

Unknown

Survival

Blunt

Penetrating

Survival

5

5

2

0

63

49

2/124

0

66

19

3

26

14

13/128

0/5

8/71

2/21

0/3

4/89

1/63

15/252

Systematic review of published reports.

180

C.J. Allen et al. / Journal of Pediatric Surgery 50 (2015) 177181

Fig. 2. Systematic review. Outcomes of ROSC, survival between blunt and penetrating.

of its use on 6 trauma patients in hemorrhagic shock [25]. Although they

concluded it is feasible to use, their indications to utilize the REBOA

were not the same indications to perform an EDT [25]. Even though

there is ongoing investigation of the REBOA in animal models, its traditional use in humans is during endovascular repair of abdominal aortic

aneurysms. Some believe its main use in trauma could be for placement

by emergency medical personnel to temporize a patient prior to transfer

to denitive care. Morrison et al. claimed the use of this technique in

patients in haemorrhagic shock, who are injured in remote areas,

would facilitate an extension of the window for salvage, and in turn

permit transfer to denitive care [26]. At our high volume level 1

trauma center, the REBOA is immediately available to the trauma and

pediatric surgeons, however it is yet to be utilized. Its use in children,

at our institution and throughout the country, is still very limited. For

these reasons, no guidelines exist for use of the REBOA in pediatric

trauma patients.

From our experiences and upon review of published reports, we

have come to several conclusions. Overall, the mortality rates are

comparable between adults and pediatric patients following EDT.

Children who sustain blunt force trauma and are without SOL at the

scene of the injury have been uniformly unsalvageable. Children who

sustain penetrating trauma and have SOL in the emergency department

or are without SOL for a short period of time prior to arrival have been

salvageable. There are no reported survivors in children less than the

age of 14 years who required an EDT after sustaining blunt force trauma.

There are no reported survivors in children less than the age of 9 years

who required an EDT after sustaining penetrating trauma.

There are limitations to this study. First, all of the data obtained from

our institution were collected retrospectively, and thus not specically

collected for research purposes. As for all data reviewed, some of the

variables may have been missing or misclassied. Also, differences in

trauma management between physicians and institutions may not

allow for generalizations to be made. Selection bias may have also

affected results, as all EDT were performed at the discretion of the

trauma physician. Publication bias also exists. It is likely other institutions have performed this procedure over the same time period,

however none were published. Although we do have access to historical

pediatric trauma registries, including the National Trauma Database

(NTDB), the information within these registries differs in comparison

to that which we analyzed for this report. In 2014, Wyrick et al., using

NTDB data from 2007 to 2010, attempted to dene the presenting

hemodynamic parameters that predict survival for pediatric patients

undergoing an EDT [27]. They reviewed 316 children (70 blunt, 240

penetrating), with a survival to discharge of 31%. They concluded that

when an EDT was performed for SBP 50 mmHg or for heart rate

70 bpm, less than 5% of patients survived. There were no survivors

of blunt trauma when SBP was 60 mmHg or pulse was 80 bpm.

However, a possible major limitation of their study is that the NTDB

does not have a specic code for an emergency resuscitative thoracotomy,

and the authors instead used exploratory thoracotomy to select their

sample. Exploratory thoracotomy can be used to infer the denition of

an EDT when a thoracotomy is performed within a short time of arrival

to the ED (Wyrick et al. used 1 hour), however there are other indications

to perform a thoracotomy (i.e. high output from chest tube with hemodynamic instability) that are not necessarily the same as for an EDT (loss of

vital signs, etc.), and EDT may sometimes be performed after 1 hour of

arrival to the ED. Also, the NTDB does not code when a patient has a

transient ROSC following an EDT. Furthermore, this trauma registry

does not specically indicate when a patient arrives without vital signs,

as this scenario can possibly lead to blank entries which may also be missing data points in the registry, nor does the NTDB indicate presence of SOL

upon arrival. These variables (presence of VS/SOL upon arrival and ROSC)

are the basis for the indication to perform an EDT and some of the

outcomes assessed by both the ACS and WTA in adults. In addition, the

NTDB by their own admission is susceptible to all of the limitations of

all convenience samples including variance in data quality which is

dependent on how well the individual hospitals implement accepted

data standards, selection bias, information bias, and missing data. For

these reasons, we needed to review in detail published reports and our

own trauma center experience in order to analyze and obtain these

data, pre-procedural conditions, and specic outcomes which are not

generally available from registry data. Finally, the relatively small sample

size prohibits denitive conclusions to be made; rather trends

established. The EDT has been even more rarely performed in the younger

group of pediatric patients, thus making it difcult to identify trends

within this specic population.

C.J. Allen et al. / Journal of Pediatric Surgery 50 (2015) 177181

Despite these limitations, this is one of the largest series report and

the rst systematic review regarding pediatric EDT. The lack of extensive

experience with this resuscitative measure in children and adolescents

still prohibits the establishment of guidelines specic to this population.

Our review allows considerable trends to be made regarding this controversial topic. Overall, although outcomes appear similar to that of the

adult population, there may be less benet in the younger pediatric

patient and in those who arrive without SOL after sustaining blunt

force injury. Also, it appears that this procedure may be overperformed in the pediatric population, which may be because of the

lack of known outcomes or overly aggressive approach in this population. Continued evaluation of this technique is warranted to develop

adequate guidelines.

Appendix A. Discussions

Presented by Dr. Casey Allen, Miami, FL

Discussant: DR. KURT HEISS (Atlanta, GA) One of the interesting things

in the literature review about this item is that when we do

emergency department thoracotomies the healthcare providers become the patients at risk and there is increased

incidence of needle sticks and injuries by those who are

participating in emergency department thoracotomies for

what you describe as unindicated indications like blunt

trauma with no vital signs at the time of arrival.

Did you look at any of the negative impact of having done

some of these thoracotomies on the providers that occurred

at your institution?

Response: Dr. CASEY ALLEN No, we did not directly analyze adverse

effects to the healthcare providers in doing these procedures

in those in whom it was frankly not indicated or presumed

indicated but that is actually a very popular question in the

trauma population.

Discussant: DR. STEVEN LEE (Los Angeles, CA) Do you have any information as far as survival to organ donation? I know that

weve had a poor survival rate but weve had a number of

patients who actually were able to harvest organs and help

contribute to other patients.

Response: DR. CASEY ALLEN Thats actually a very interesting question

because were looking into that right now in adults as well as

children. However, I dont have that information available at

this time.

Steven Stylianos (New York, NY) Thats a very important report that

you just gave from one of the most sophisticated and effective

trauma centers in our country, so thank you for that.

Have you taken the next step to incorporate these ndings

into your trauma algorithms?

Response: DR. CASEY ALLEN I think its just important to recognize the

fact that there have not been any blunt survivors under the age

of 14 and again there are a lot of reasons to why that may be,

including the different hemodynamics of a pediatric patient,

proportional size of their head and other organs. Our experience with children who arrive without signs of life, the victims

of blunt injury have had very poor outcomes. For this reason,

we do not perform this procedure on those patients anymore

at our institution.

181

Unidentied speaker I notice you have a 32% incidence of gunshot

wounds. In our population in Australia, we serve a population

of 1.2 million at a womens and childrens hospital in Adelaide

and we may see one gunshot wound a year and many a year

goes by without a single gunshot wound. Just a huge contrast.

References

[1] Gratz RR. Accidental injury in childhood: a literature review on pediatric trauma.

J Trauma 1979;19(8):5515.

[2] Rivara FP. Epidemiology of violent deaths in children and adolescents in the United

States. Pediatrician 1983;12(1):310.

[3] Colombani PM, Buck JR, Dudgeon DL, et al. One-year experience in a regional

pediatric trauma center. J Pediatr Surg 1985;20(1):813.

[4] Haller Jr JA, Shorter N, Miller D, et al. Organization and function of a regional

pediatric trauma center: does a system of management improve outcome? J Trauma

1983;23(8):6916.

[5] Mahoney WJ, D'Souza BJ, Haller JA, et al. Long-term outcome of children with severe

head trauma and prolonged coma. Pediatrics 1983;71(5):75662.

[6] Beaver BL, Colombani PM, Buck JR, et al. Efcacy of emergency room thoracotomy in

pediatric trauma. J Pediatr Surg 1987;22(1):1923.

[7] Boatright DH, Byyny RL, Hopkins E, et al. Validation of rules to predict emergent

surgical intervention in pediatric trauma patients. J Am Coll Surg 2013;216(6):

1094102 [1102 e1-6].

[8] Easter JS, Vinton DT, Haukoos JS. Emergent pediatric thoracotomy following

traumatic arrest. Resuscitation 2012;83(12):15214.

[9] Hofbauer M, Hup M, Figl M, et al. Retrospective analysis of emergency room thoracotomy in pediatric severe trauma patients. Resuscitation 2011;82(2):1859.

[10] Langer JC, Hoffman MA, Pearl RH, et al. Survival after emergency department thoracotomy in a child with blunt multisystem trauma. Pediatr Emerg Care 1989;5(4):2556.

[11] Powell RW, Gill EA, Jurkovich GJ, et al. Resuscitative thoracotomy in children and

adolescents. Am Surg 1988;54(4):18891.

[12] Rothenberg SS, Moore EE, Moore FA, et al. Emergency department thoracotomy in

childrena critical analysis. J Trauma 1989;29(10):13225.

[13] Sheikh AA, Culbertson CB. Emergency department thoracotomy in children: rationale for selective application. J Trauma 1993;34(3):3238.

[14] Sherman MM, Saini VK, Yarnoz MD, et al. Management of penetrating heart wounds.

Am J Surg 1978;135(4):5538.

[15] Baker CC, Thomas AN, Trunkey DD. The role of emergency room thoracotomy in

trauma. J Trauma 1980;20(10):84855.

[16] Cogbill TH, Moore EE, Millikan JS, et al. Rationale for selective application of emergency department thoracotomy in trauma. J Trauma 1983;23(6):45360.

[17] Nirula R, Maier R, Moore E, et al. Scoop and run to the trauma center or stay and play

at the local hospital: hospital transfer's effect on mortality. J Trauma 2010;69(3):

5959 [discussion 599601].

[18] Smith RM, Conn AK. Prehospital carescoop and run or stay and play? Injury 2009;

40(Suppl. 4):S236.

[19] Advanced trauma life support for doctors ATLS: manuals for coordinators and faculty.

8th ed. Chicago, IL: American College of Surgeons; 2008.

[20] Moore EE, Knudson MM, Burlew CC, et al. Dening the limits of resuscitative emergency

department thoracotomy: a contemporary Western Trauma Association perspective.

J Trauma 2011;70(2):3349.

[21] Burlew CC, Moore EE, Moore FA, et al. Western Trauma Association critical decisions in

trauma: resuscitative thoracotomy. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2012;73(6):135963.

[22] Fallat ME. Pediatric Trauma. In: Mulholland MW, Lillemoe KD, Doherty GM, Maier

RV, Upchurch GR, editors. Greeneld's surgery: scientic principles and practice.

4th ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2006;468:46779.

[23] Working Group. Ad Hoc Subcommittee on Outcomes, American College of SurgeonsCommittee on Trauma. Working Group AHSoOACoSCoT: practice management guidelines for emergency department thoracotomy. J Am Coll Surg 2001;193(3):3039.

[24] Flynn TC, Ward RE, Miller PW. Emergency department thoracotomy. Ann Emerg

Med 1982;11(8):4136.

[25] Brenner ML, Moore LJ, DuBose JJ, et al. A clinical series of resuscitative endovascular

balloon occlusion of the aorta for hemorrhage control and resuscitation. J Trauma

Acute Care Surg 2013;75(3):50611.

[26] Morrison JJ, Lendrum RA, Jansen JO. Resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of

the aorta (REBOA): a bridge to denitive haemorrhage control for trauma patients in

Scotland? Surgeon 2014;12(3):11920.

[27] Wyrick DL, Dassinger MS, Bozeman AP, et al. Hemodynamic variables predict the

outcome of emergency thoracotomy in the pediatric trauma population. J Pediatr

Surg 2014;49(9):13824.

You might also like

- Usefulness of Cardiothoracic Chest Ultrasound in The Management of Acute Respiratory Failure in Critical Care Practice (2013)Document7 pagesUsefulness of Cardiothoracic Chest Ultrasound in The Management of Acute Respiratory Failure in Critical Care Practice (2013)Enzo_AENo ratings yet

- Bowel Obstruction Due To Diaphragmatic Injury After Penetrating Thoracic Trauma (2014)Document3 pagesBowel Obstruction Due To Diaphragmatic Injury After Penetrating Thoracic Trauma (2014)Enzo_AENo ratings yet

- Tendencia en El Estudiante de Medicina A Ejercer Como Médico General o Especialista (2009)Document8 pagesTendencia en El Estudiante de Medicina A Ejercer Como Médico General o Especialista (2009)Enzo_AENo ratings yet

- Vitamin D Deficiency and Risk of Acute Lung Injury in Severe Sepsis and Severe Trauma (2014)Document10 pagesVitamin D Deficiency and Risk of Acute Lung Injury in Severe Sepsis and Severe Trauma (2014)Enzo_AENo ratings yet

- Chest Drainage (2012)Document9 pagesChest Drainage (2012)Enzo_AENo ratings yet

- Disruptive Technology in The Treatment of Thoracic Trauma (2013)Document8 pagesDisruptive Technology in The Treatment of Thoracic Trauma (2013)Enzo_AENo ratings yet

- Bedside Thoracic Ultrasonography of The Fourth Intercostal Space Reliably Determines Safe Removal of Tube Thoracostomy After Traumatic Injury 2012Document1 pageBedside Thoracic Ultrasonography of The Fourth Intercostal Space Reliably Determines Safe Removal of Tube Thoracostomy After Traumatic Injury 2012Enzo_AENo ratings yet

- Cardio-Embolic Stroke Following Remote Blunt Chest Trauma (2013)Document4 pagesCardio-Embolic Stroke Following Remote Blunt Chest Trauma (2013)Enzo_AENo ratings yet

- Systemic Inflammation and Fracture Healing (2011)Document5 pagesSystemic Inflammation and Fracture Healing (2011)Enzo_AENo ratings yet

- Conservative Management of Large Intrapulmonary Haemorrhage Following Penetrating Chest Trauma (2007)Document4 pagesConservative Management of Large Intrapulmonary Haemorrhage Following Penetrating Chest Trauma (2007)Enzo_AENo ratings yet

- Trauma Airway Management (2014)Document9 pagesTrauma Airway Management (2014)Enzo_AENo ratings yet

- Which Is Better To Multiple Rib Fractures, Surgical Treatment or Conservative Treatment (2015)Document7 pagesWhich Is Better To Multiple Rib Fractures, Surgical Treatment or Conservative Treatment (2015)Enzo_AENo ratings yet

- Tranexamic Acid in Trauma. ¿How Should We Use It (2013)Document12 pagesTranexamic Acid in Trauma. ¿How Should We Use It (2013)Enzo_AENo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5783)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- HR CONCLAVE DraftDocument7 pagesHR CONCLAVE DraftKushal SainNo ratings yet

- Business Statistics: Methods For Describing Sets of DataDocument103 pagesBusiness Statistics: Methods For Describing Sets of DataDrake AdamNo ratings yet

- Pathophysiology of Alzheimer's Disease With Nursing ConsiderationsDocument10 pagesPathophysiology of Alzheimer's Disease With Nursing ConsiderationsTiger Knee100% (1)

- Photobiomodulation With Near Infrared Light Helmet in A Pilot Placebo Controlled Clinical Trial in Dementia Patients Testing MemorDocument8 pagesPhotobiomodulation With Near Infrared Light Helmet in A Pilot Placebo Controlled Clinical Trial in Dementia Patients Testing MemorarexixNo ratings yet

- Jim Kwik - 10 Morning Habits Geniuses Use To Jump Start The Brain - YouTube Video Transcript (Life-Changing-Insights Book 15) - Stefan Kreienbuehl PDFDocument5 pagesJim Kwik - 10 Morning Habits Geniuses Use To Jump Start The Brain - YouTube Video Transcript (Life-Changing-Insights Book 15) - Stefan Kreienbuehl PDFCarlos Silva100% (11)

- Entrepreneurial Mindset and Opportunity RecognitionDocument4 pagesEntrepreneurial Mindset and Opportunity RecognitionDevin RegalaNo ratings yet

- Y3 Module 1 QuizDocument6 pagesY3 Module 1 QuizMohd HattaNo ratings yet

- Problem Set 1Document5 pagesProblem Set 1sxmmmNo ratings yet

- Unified Field Theory - WikipediaDocument24 pagesUnified Field Theory - WikipediaSaw MyatNo ratings yet

- Stories of Narada Pancaratra and Lord Krishna's protection of devoteesDocument9 pagesStories of Narada Pancaratra and Lord Krishna's protection of devoteesPedro RamosNo ratings yet

- Soal Uts Clea 2022-2023Document2 pagesSoal Uts Clea 2022-2023estu kaniraNo ratings yet

- Application For Enrolment Electoral Roll 20132Document1 pageApplication For Enrolment Electoral Roll 20132danielNo ratings yet

- Literary Criticism ExamDocument1 pageLiterary Criticism ExamSusan MigueNo ratings yet

- 2014 JC2 H2 Econs Prelim Paper 2Document3 pages2014 JC2 H2 Econs Prelim Paper 2Ezra Notsosure WongNo ratings yet

- Assignment Histogram and Frequency DistributionDocument6 pagesAssignment Histogram and Frequency DistributionFitria Rakhmawati RakhmawatiNo ratings yet

- Challenges of Quality Worklife and Job Satisfaction for Food Delivery EmployeesDocument15 pagesChallenges of Quality Worklife and Job Satisfaction for Food Delivery EmployeesStephani shethaNo ratings yet

- Grammar Dictation ExplainedDocument9 pagesGrammar Dictation ExplainedlirutNo ratings yet

- Unesco Furniture DesignDocument55 pagesUnesco Furniture DesignHoysal SubramanyaNo ratings yet

- CSR & Corporate FraudDocument18 pagesCSR & Corporate FraudManojNo ratings yet

- Algebra - QuestionsDocument13 pagesAlgebra - Questionsdhruvbhardwaj100% (1)

- Futura.: Design by Zoey RugelDocument2 pagesFutura.: Design by Zoey RugelZoey RugelNo ratings yet

- Permutations & Combinations Practice ProblemsDocument8 pagesPermutations & Combinations Practice Problemsvijaya DeokarNo ratings yet

- 5-Qualities-of-a-Successful-Illustrator 2Document42 pages5-Qualities-of-a-Successful-Illustrator 2Jorge MendozaNo ratings yet

- Metaverse in Healthcare-FADICDocument8 pagesMetaverse in Healthcare-FADICPollo MachoNo ratings yet

- LVMPD Use of Force PolicyDocument26 pagesLVMPD Use of Force PolicyFOX5 VegasNo ratings yet

- Worksheets Section 1: Develop Quality Customer Service PracticesDocument3 pagesWorksheets Section 1: Develop Quality Customer Service PracticesTender Kitchen0% (1)

- Data NormalisationDocument10 pagesData Normalisationkomal komalNo ratings yet

- Bear Fedio PDFDocument14 pagesBear Fedio PDFPaula HarrisNo ratings yet

- SESSION 8 - Anti-Malaria DrugsDocument48 pagesSESSION 8 - Anti-Malaria DrugsYassboy MsdNo ratings yet

- Cultural Diversity and Relativism in SociologyDocument9 pagesCultural Diversity and Relativism in SociologyEllah Gutierrez100% (1)