Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Kolestasis

Uploaded by

Nur Ainatun NadrahOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Kolestasis

Uploaded by

Nur Ainatun NadrahCopyright:

Available Formats

RECOMMENDATIONS

Management of Neonatal Cholestasis: Consensus Statement of the

Pediatric Gastroenterology Chapter of Indian Academy of Pediatrics

VIDYUT BHATIA, *ASHISH BAVDEKAR, $JOHN MATTHAI, #YOGESH WAIKAR AND ANUPAM SIBAL

From Apollo Center for Advanced Pediatrics, Indraprastha Apollo Hospital, New Delhi; *Department of Pediatrics, King Edwards

Memorial Hospital, Pune; $Department of Pediatrics, PSG Institute of Medical Sciences, Coimbatore and #Pediatric

Gastroenterology Clinic, Care hospital, Nagpur, India.

Correspondence to: Dr Vidyut Bhatia, Apollo Center for Advanced Pediatrics, Indraprastha Apollo Hospital, New Delhi 110 076,

India. drvidyut@me.com

Justification: Neonatal cholestasis is an important cause of

chronic liver disease in young children. Late referral and lack of

precise etiological diagnosis are reasons for poor outcome in

substantial number of cases in India. There is a need to create

better awareness among the pediatricians, obstetricians and

primary care physicians on early recognition, prompt evaluation

and referral to regional centers.

from India and the West, to discuss current diagnostic and

management practices in major centers in India, and to identify

various problems in effective diagnosis and ways to improve the

overall outcome. Current problems faced in different areas were

discussed and possible remedial measures were identified. The

ultimate aim would be to achieve results comparable to the

West.

Process: Eminent national faculty members were invited to

participate in the process of forming a consensus statement.

Selected members were requested to prepare guidelines on

specific issues, which were reviewed by two other members.

These guidelines were then incorporated into a draft statement,

which was circulated to all members. A round table conference

was organized; presentations, ensuing discussions, and

opinions expressed by the participants were incorporated into

the final draft.

Recommendations: Early recognition, prompt evaluation and

algorithm-based management will improve outcome in neonatal

cholestasis. Inclusion of stool/urine color charts in well baby

cards and sensitizing pediatricians about differentiating

conjugated

from

the

more

common

unconjugated

hyperbilirubinemia are possible effective steps. Considering the

need for specific expertise and the poor outcome in suboptimally managed cases, referral to regional centers is

warranted.

Objectives: To review available published data on the subject

Keywords: Cholestatic jaundice, Neonate, Practice guidelines.

Laboratories in many private and other medical centers are

now able to do newer tests for precise diagnosis. This

meeting was held to discuss the impact of those programs

and to make appropriate changes in the management

protocol in the light of recent advances in the subject.

eonatal cholestasis (NC) is being increasingly

recognized as an important cause of chronic

liver disease in infants and young children.

The etiology and management of cholestasis

has changed significantly since the consensus statement

last published in 2000 [1]. Three objectives were

identified at the previous meeting. First, age at which

infants are referred to tertiary care centers is very late for

effective evaluation and management and steps need to

be taken to address this problem. Second, tertiary centers

with pediatric gastroenterology units should follow a

uniform protocol of evaluation, and third, the

investigation facilities at some centers need to be

strengthened, so that a more precise final diagnosis,

particularly metabolic disorders, can be arrived at.

DEFINITION

Neonatal cholestasis is defined as conjugated

hyperbilirubinemia occurring in the newborn as a

consequence of diminished bile flow. Conjugated

hyperbilirubinemia in a neonate is defined as a serum

direct/conjugated bilirubin concentration greater than 1.0

mg/dL if the total serum bilirubin (TSB) is <5.0 mg/dL or

greater than 20 percent of TSB if the TSB is >5.0 mg/dL

[4]. It is important to note that the diazo method of

estimating bilirubin, that is still practiced in many Indian

centers, tends to overestimate the direct fraction at lower

bilirubin levels. The group however felt that the above

mentioned definition has to be retained since it is an

internationally accepted one.

A number of steps including a public campaign on

Yellow alert and educational programs at pediatric

meetings were since held to address the key issues [2,3].

The algorithm put in place in 2001 was followed at almost

all major centers, until newer advances were reported.

INDIAN PEDIATRICS

203

VOLUME 51__MARCH 15, 2014

BHATIA, et al.

MANAGEMENT OF NEONATAL CHOLESTASIS

Conjugated hyperbilirubinemia at any age in a

newborn is pathological and requires evaluation. Any

newborn with jaundice and dark yellow urine staining the

diaper with or without pale stools should be strongly

suspected to have NC. Such babies must be referred to an

appropriate center for further investigations and

treatment at the earliest [1]. Sick newborns and younger

infants with deranged liver function tests, particularly

uncorrected coagulopathy, require urgent referral to rule

out infective or metabolic causes of NC.

it is suggestive of cholestasis. The sensitivity, specificity,

and positive predictive value of pale stools for the

detection of biliary atresia (BA) before 60 days as

determined by a color-coded stool chart was noted to be

89.7%, 99.9% and 28.6%, respectively [19]. Although

cholestasis is known to occur in babies with early onset

sepsis [14]. Yet simultaneous screening should be done

for metabolic causes. Galactosemia, a treatable cause,

may be present even in babies with culture proven sepsis.

Babies with tyrosinemia, herpes infection and congenital

hemochromatosis may present in a sick state early in life,

and their recognition and treatment needs to be

incorporated [20]. Non-normalization of liver function

tests (LFTs) even after treatment with appropriate

antibiotics is a pointer towards an underlying metabolic

cause for sepsis [14].

ETIOLOGY

NC affects 1 in 2500 infants in the West [4,5]. In India it

constitutes 19% to 33% of all chronic liver diseases in

children reporting to tertiary care hospitals [1,6-8].

Table I summarizes the etiologic profile of NC in India.

Hepatocellular causes constitute 45% to 69% while

obstructive causes account for 19% to 55% of all cases

[1,6-12].

Yachha, et al. showed that the age of onset of

jaundice in BA was 3-12 days and that of hepatocellular

causes was 16-24 days [2]. However, the mean age of

presentation to a tertiary care center was 2.83.9 months

compared to the desired age of evaluation, that is 4-6

weeks [2,3,15]. Babies with BA appear well and have

normal growth and development in spite of their

jaundice, and this leads to parents and physicians

underestimating the seriousness of the problem [3]. Many

health care professionals also have a misconception that

all well babies with icterus have physiological jaundice

(which is unconjugated and associated with normal urine

color). The group felt that it was a matter of concern that

in India the average age of presentation to tertiary care

centers has shown little change in the last decade. The

group felt that there is a need for creating more awareness

among pediatricians and obstetricians on NC and this can

be achieved through continuing medical education

(CME) programs with the speakers giving the same

message by highlighting the recommendations of this

consensus statement. Enlarging the scope of the yellow

alert to include the whole country through visual and

print media would also be beneficial. The Group

recommended urine and stool color assessment

(minimum 3 stool samples) by the mother and physician

in a stool color card incorporated in all well baby cards

(Indian Academy of Pediatrics and the Government of

India cards). The group also felt that the Taiwanese

experience with stool color cards (subsequently

replicated in other countries) should be possible in India

as well [21].

While 20 to 30% of cases of NC were idiopathic in

earlier studies, [1,6,7,9], recent reports documented this

proportion to be lower [2,8,13-18]. The group felt that

this emphasizes the need for more exhaustive work up

than was recommended earlier. A recent publication with

exhaustive workup has shown that Pi-Z and Pi-S alleles

responsible for alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency may be rare

in our population [7].

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

Jaundice in newborns is most commonly physiological or

due to ABO/Rh hemolytic incompatibility. However, if

jaundice is associated with dark urine and/or pale stools,

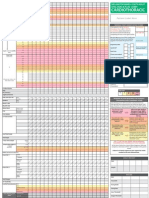

TABLE I ETIOLOGIC PROFILE

INDIA

Etiologic Factor

OF

NEONATAL CHOLESTASIS

N-1008* (%)

IN

N-420#(%)

Obstructive causes

Biliary atresia

34

30

Choledochal cysts

Infections

17

18

Metabolic causes

12

Miscellaneous

Unknown etiology

30

31

Ductal paucity

Undifferentiated

1.2

Hepatocellular causes

*Based

Persistent cholestasis from any cause leads to liver

damage and cirrhosis. Therefore, determining the

specific etiology (medical or surgical) at the earliest is

critical. Also, the outcome of Kasai portoenterostomy

(PE) is directly related to the age of surgery and the

on cumulative data from eight tertiary care centers [1];

#Data from the largest single series (7).

INDIAN PEDIATRICS

204

VOLUME 51__MARCH 15, 2014

BHATIA, et al.

MANAGEMENT OF NEONATAL CHOLESTASIS

expertise of the treating unit. PE when performed earlier

than 60 days of age established adequate bile flow in

64.7% of patients compared with 31.8% when performed

later [22,23]. Improved outcome is also noted in centers

with a higher case load [24]. In the United Kingdom, a

center performing >5 Kasai PE per year, reported

significantly better outcome [25]. Hence, babies

suspected to have BA require early referral to an

appropriate center with expertise in performing PE.

by specific radiological and histopathological tests

(Fig. 1). The principal diagnostic concerns are to

differentiate hepatocellular diseases from anatomical

disorders, and diseases that are managed medically from

those requiring surgical intervention. The most important

initial investigation is to establish cholestasis by measuring

serum bilirubin (total and differential) levels. Severity of

liver dysfunction can be measured by estimating the

prothrombin time or international normalized ratio (INR)

and serum albumin. No single laboratory or imaging test

exists which differentiates biliary obstruction from other

causes of NC reliably in all cases. The serum

transaminases are sensitive indicators of hepatocellular

injury, but lack specificity and prognostic value. High

alkaline phosphatase levels can be seen in biliary

obstruction, but has very low specificity. Gamma-glutamyl

transpeptidase (GGTP) is a marker of biliary obstruction

and is elevated in most cholestatic disorders;

paradoxically low or normal levels are found in patients

with progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis (PFIC)

and disorders of bile acid synthesis [26].

INVESTIGATIONS

Most centers have been following the protocol that was

outlined in the earlier consensus statement. However in the

light of recent publications and better laboratory support,

modifications are required in the evaluation and

management protocol. The group felt that laboratory

facilities and histopathology support has improved

tremendously in the last decade and hence better work up

is now possible in many centers. The initial evaluation of

an infant with NC includes a complete liver function test

(LFT), thyroid function test, and a sepsis screen followed

NC

Sick

Not Sick

Sepsis Screen +ve

Sepsis Screen ve

Pale stools

Pigmented stools

Fasting USG (see

for contractility

post-feed)

GCT*, Fasting USG

(If the USG show a

choledochal cyst,

the child needs to be

referred for

surgery), Metabolic

tests, Genetic tests,

Liver Biopsy

Test for CMV, HSV, Urinary

Succinylacetone, Ferritin,

GALT if urine reducing sugar

is positive

Normal

------

Treat sepsis

(Galactosemia

needs to be

excluded by urine

reducing sugar by

Benedicts test as

sepsis can be

associated with

Galactosemia)

Liver biopsy

Small gall

bladder

Absent gall

bladder

Choledochal

cyst

Biliary atresia to be

excluded (see Fig.2)

Specific

treatment

Surgery

-----------

Specific

treatment

Optional

* GGT is normal in PFIC

I and II and some inborn

errors of bile acid

metabolism

FIG. 1 Diagnostic algorithm for management of neonatal cholestasis (Part 1).

INDIAN PEDIATRICS

205

VOLUME 51__MARCH 15, 2014

BHATIA, et al.

MANAGEMENT OF NEONATAL CHOLESTASIS

Abdominal ultrasonography may provide findings

suggestive of BA and can also be used to confirm the

existence of other surgically treatable conditions like

choledochal cyst, inspissated bile plug syndrome and

choledocholithiasis.

Abdominal

ultrasonography

findings described in BA include the triangular cord sign

[27], abnormal gallbladder morphology (not visualized

or length <1.9 cm or lack of smooth/complete echogenic

mucosal lining with an indistinct wall or irregular/lobular

contour) [19], no contraction of the gallbladder after oral

feeding and non-visualized common bile duct (CBD). A

distended gall bladder, however, does not rule out a

proximal BA with a distal patent bile duct and mucus

filled gallbladder. It is recommended that ultrasound

should be done after 4 hours of fasting.

structure of the gene and the presence of novel mutations

[30,31]. Hereditary fructose intolerance (HFI) is not an

uncommon cause of neonatal cholestasis in our country as

there are many states where sugar water continues to be

given to newborns until lactation is fully established. It

should be considered in clinical settings where sucrose or

fruit juices have been given to babies. Assay of aldolase B

enzyme in liver biopsy sample confirms HFI. Fructose

challenge test can make the child very ill and is now

obsolete. Plasma tyrosine levels are unreliable in the

diagnosis of tyrosinemia. Measurement of urinary

succinylacetone and succinyl acetoacetate or assay of the

FAH gene is diagnostic [32]. Among the congenital

infections, cytomegalovirus (CMV) is most commonly

implicated. Serum IgM level is unreliable in diagnosis

and should not be used. Assay of pp65 antigen and CMV

polymerase chain reaction (PCR) are more specific and

reliable, if the biochemical tests and histology are

consistent with the diagnosis. Markedly raised serum

ferritin and uncorrected coagulopathy are suggestive of

hemochromatosis that may be confirmed by a buccal

mucosal biopsy.

Hepatobiliary-imino-di-acetic acid (HIDA) scan has

limited role in evaluation of NC especially if the baby has

clearly documented pale or pigmented stools. The time

required (5-7 days) for priming before the scan,

especially in patients who are referred late, is a limitation.

The group felt that good-quality HIDA scan may not be

available everywhere in our country, and therefore,

delaying the liver biopsy for it is not justified. Performing

a HIDA scan is optional and one may go for a liver biopsy

straightaway (Fig. 2). HIDA is, however, useful in the

diagnosis of the uncommon causes like spontaneous

perforation of the bile duct [28]. Intra-operative

cholangiogram (IOC) remains the gold standard for

diagnosis of BA.

A two part diagnostic algorithm to help in the

management of NC is given in Fig.1 and Fig. 2.

TREATMENT

General Medical Management

Most infants with NC are underweight and will need

nutritional support. The goal is to provide adequate

calories to compensate for steatorrhea and to prevent/

treat malnutrition. The calorie requirement is

approximately 125% of the recommended dietary

allowance (RDA) based on ideal body weight [33]. In

breastfed infants, breastfeeding should be encouraged

and medium-chain triglyceride (MCT) oil should be

administered in a dose of 1-2 mL/kg/d in 2-4 divided

doses in expressed breast milk [34]. In older infants, a

milk-cereal-mix fortified with MCT is preferred. Adding

puffed rice powder and MCT to milk can make feeds

energy-dense. Essential fatty acids should constitute 23% of the energy provided. Vegetable protein at 2-3 g/kg/

d is recommended [34].

Liver biopsy is an essential investigation in the

evaluation of NC. Early recognition of BA by liver biopsy

can avoid unnecessary laparotomy (5). The characteristic

histopathology features of BA are bile duct proliferation,

bile plugs in ducts, fibrosis and lymphocytic infiltrates in

the portal tracts. The reported sensitivity, specificity and

accuracy of liver biopsy in the diagnosis of BA are 8999%, 82-98% and 60-95%, respectively [16].

Percutaneous liver biopsy in early infancy under local

anesthesia and sedation is a safe procedure, if performed

by competent physicians [29]. The group opined that the

biopsy must be interpreted by an experienced pathologist

in conjunction with the clinical profile and results of the

other investigations. In cases of doubt, a second opinion

should be sought.

Infants with cholestasis require supplementation with

fat-soluble vitamins administered orally as water-soluble

preparations. Suggested daily vitamin and mineral

supplementation are given in Table II. In treatment of

vitamin deficiencies, standard deficiency protocols

should be followed. 1,25 dihydroxy Vitamin D3 (0.05-0.2

ug/kg/d) is recommended in the presence of significant

bone changes or patients having severe cholestasis [34].

Vitamin K is administered at a dose of 5 mg

In galactosemia, urine is positive for non-glucose

reducing substances while the infant is on lactose feeds.

E. coli sepsis in the presence of liver cell dysfunction is

very characteristic of galactosemia. Assay of Galactose-1

phosphate uridyl transferase (GALT) enzyme is used for

confirmation. Mutational analysis of the GALT gene from

Indian subjects has revealed heterogeneity in the

INDIAN PEDIATRICS

206

VOLUME 51__MARCH 15, 2014

BHATIA, et al.

MANAGEMENT OF NEONATAL CHOLESTASIS

Billary atresia to be

excluded

(Baby not sick, pale stools, small or absent gall bladder on

fasting ultrasound)

Age <6 weeks

Age 6 weeks

Age >90 days with ascites

Age >120 days

-------

HIDA scan after 3

days of priming

Excretion

No Excretion

Refer to a transplant center

Liver Biopsy

Specific

treatment

Inconclusive

Biliary atresia

Intra operative Cholangiogram +

Kasai operation

----------- Optional

FIG. 2 Diagnostic algorithm to help in the management of neonatal cholestasis (Part 2).

(5-10 mg/kg/d), and phenobarbitone (510 mg/kg/d).

Symptom chart should be made for pruritus. Depending

on severity and response to previous agent, add-on drug

can be considered. Appropriate antibiotics depending on

the site of infection and culture sensitivity reports need to

be administered in patients with bacterial sepsis.

intramuscular, subcutaneously or intravenously, at

diagnosis to correct the coagulopathy. If the INR is

markedly prolonged, intramuscular injections should be

avoided. Vitamin supplementation should be continued

till 3 months after resolution of jaundice [35].

Specific treatment

Kasais PE consists of removal of the atretic extrahepatic tissue and a Roux-en-Y jejunal loop anastomosis to

the hepatic hilum. PE may be considered successful if

serum bilirubin normalizes after surgery. In general, over

half the patients normalize their bilirubin after Kasais PE if

performed within six months [36]. About 20% of all

patients undergoing Kasais PE during infancy survive into

adulthood with their native liver [36,37]. In children with

progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis (PFIC)

without decompensated cirrhosis, external and internal

biliary diversion has been shown to be of benefit [38].

Surgery gives excellent results for choledochal cysts and

should be performed as soon as the diagnosis is made. The

recent consensus statement of the Pediatric

Gastroenterology chapter on Acute liver failure gives more

details on the management of liver failure in NC [39].

Special infant formula and diets are recommended for

children with specific diagnosis (galactosemia,

fructosemia and tyrosinemia). However these formulae

are currently not available in India. The group feels that

steps must be taken to make them available at the earliest.

Treatment with nitisinone (1 mg/kg/d) in addition to

dietary restriction leads to rapid reduction of toxic

metabolites in tyrosinemia. Specific therapy is

recommended for patients with CMV (associated

neurological involvement), herpes and toxoplasmosis

related cholestasis. There is no role for steroids in

idiopathic neonatal hepatitis.

In infants with pruritus due to severe cholestasis, the

group recommended, in the following order:

Ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) (20 mg/kg/d), rifampicin

INDIAN PEDIATRICS

207

VOLUME 51__MARCH 15, 2014

BHATIA, et al.

MANAGEMENT OF NEONATAL CHOLESTASIS

TABLE II SUGGESTED DAILY VITAMIN AND MINERAL

REQUIREMENTS IN INFANTS WITH CHOLESTASIS

Route

Dose*

Vitamin A#

Oral

5000-25,000 IU/d

Vitamin D

Oral

400-1200 IU/d

Vitamin E

Oral

50-400 IU/d or 15-25 IU/

kg/d of TPGS form if

available

Vitamin K$

Oral

2.5 twice/week to 5 mg/d

Parenteral

2-5 mg IM, SC or IV

4 weekly

Water soluble vitamins Oral

1-2 times the RDA

Calcium**

Oral

20-100 mg/kg/d

Phosphorus

Oral

25-50 mg/kg/d

Zinc

Oral

1 mg/kg/d

Magnesium

Oral

1-2 mEq/kg/d

Intravenous 0.3-0.5 mEq/ kg over

3 hours of 50% solution

Elemental iron

Oral

5-6 mg/kg/d

Adapted from Ref. 39

*Doses are provided as a guide only and will need to be adjusted

based on response and levels of the vitamins. #Careful monitoring

required as Vitamin A itself is hepatotoxic; $Vitamin K1 preparation

preferred, as it is safe for G6PD deficient individuals; **Calcium should

always be supplemented along with Vitamin D.

Liver transplantation

Liver Transplantation, the standard therapy for

decompensated cirrhosis due to any cause, is now well

established in India as well [40]. Any baby, who has had

Kasais PE and the bilirubin remains >6 mg/dL, three

months after surgery, should be referred to a transplant

center. Babies with BA who present with decompensated

cirrhosis (low albumin, prolonged INR, ascites) are not

likely to improve with a Kasai PE and should be referred

for liver transplantation. Of the 355 transplants in children

that have been performed in India till 2012, 30% have been

for BA [41]. Living related liver transplantation (the vast

majority of liver transplants in India are living related),

performed at experienced centers, is associated with

favorable outcomes, with 5- and 10-year survival rates of

98% and 90%, respectively [42-44].

APPENDIX

List of Invited Participants

AK Patwari, Akshay Kapoor, Akshay Saxena, Alok Hemal,

Anjali Kulkarni, Anshu Srivastava, Anupam Sibal (AS), Ashish

Bavdekar (AB), BD Dwivedi, BR Thapa, Dhanasekhar K., John

Mathai (JM), Lalit Bharadia, Malathi Sathiyasekharan, Manoja

Das, Narendra K Arora, Neelam Mohan*, Nishant Wadhwa,

Pankaj Vohra, Pawan Rawal*, Praveen Kumar, Rajeev Tomar,

Rajiv Redkar, Rakesh Mishra, SK Mittal*, S Srinivas, Sarath

Gopalan, Seema Alam*, Shrish Bhatnagar*, Subash Gupta, Sujit

NC constitutes almost one-third of children with

chronic liver disease in major hospitals in India. BA,

NH and metabolic causes are the most important

causes in India.

INDIAN PEDIATRICS

Malnutrition adversely affects the outcome in infants

with cholestasis. Nutritional support and vitamin/

mineral supplementation is recommended in all babies

with NC. Special formulae may have a role in select

cases.

When NC leads to liver failure, LT should be offered.

Success rates in India are comparable to those in the

West.

Contributors: VB composed the first draft of this statement,

which after input from AB, JM, YW and AS was circulated to all

the participants.

Funding: Rakhi and Adish Oswal funded the Round Table

Conference in memory of their son Kunwar Viren Oswal.

Competing interests: None stated

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Early identification of the cause is essential for a

favorable outcome. This requires specific biochemical

tests, imaging studies and interpretation of

histopathology by experienced personnel and is now

possible in major centers all over India.

The overall outcome in India is far from satisfactory,

due to late referral. The mean age at presentation in

tertiary care centers is still over 3 months compared to

recommended age of less than 60 days.

To ensure early referral, there is an urgent need to

sensitize pediatricians, obstetricians and other

primary-care physicians on the need for early

evaluation. Yellow alert should be extended to an AllIndia level and the stool color card should be

incorporated in the well-baby cards of IAP and the

Government of India.

Metabolic diseases (e.g. galactosemia, fructosemia,

hemochromatosis, tyrosinemia) and inherited diseases

like PFIC are increasingly being diagnosed in tertiary

centers. Establishment of regional referral labs will

enable greater diagnosis of causes of NC.

Ultrasound, isotope scan and liver biopsy

interpretation in experienced hands are effective in

ruling out surgical causes in a majority of cases. If BA

cannot be ruled out with certainty, an experienced

surgeon should perform a laparotomy andintraoperative cholangiography.

208

VOLUME 51__MARCH 15, 2014

BHATIA, et al.

MANAGEMENT OF NEONATAL CHOLESTASIS

Chowdhary*, Sumathi B., Sutapa Ganguly, Ujjal Poddar*, VS

Sankaranarayanan, Veena Malhotra, Vibhor Borkar, Vidyut

Bhatia (VB), Vishnu Biradar, Yogesh Waikar (YW)

*Contributed but could not attend the Round Table Conference

th

on 8 December 2012.

16. Rastogi A, Krishnani N, Yachha SK, Khanna V, Poddar U,

Lal R. Histopathological features and accuracy for

diagnosing biliary atresia by prelaparotomy liver biopsy in

developing countries. J Gastroenterol Hepatol.

2009;24:97-102.

17. Shah I, Bhatnagar S. Clinical profile of chronic

hepatobiliary disorders in children: experience from

tertiary referral centre in Western India. Trop

Gastroenterol. 2010;31:108-10.

18. Yachha SK, Mohindra S. Neonatal cholestasis syndrome:

Indian scene. Ind J Pediatr. 1999;66:S94-6.

19. Chen SM, Chang MH, Du JC, Lin CC, Chen AC, Lee HC,

et al. Screening for biliary atresia by infant stool color card

in Taiwan. Pediatrics. 2006;117:1147-54.

20. Burton BK. Inborn errors of metabolism in infancy: a guide

to diagnosis. Pediatrics. 1998;102:E69.

21. Lien TH, Chang MH, Wu JF, Chen HL, Lee HC, Chen AC,

et al. Effects of the infant stool color card screening

program on 5-year outcome of biliary atresia in Taiwan.

Hepatology. 2011;53:202-8.

22. Lally KP, Kanegaye J, Matsumura M, Rosenthal P, Sinatra

F, Atkinson JB. Perioperative factors affecting the outcome

following repair of biliary atresia. Pediatrics. 1989;83:7236.

23. Serinet MO, Wildhaber BE, Broue P, Lachaux A, Sarles J,

Jacquemin E, et al. Impact of age at Kasai operation on its

results in late childhood and adolescence: a rational basis

for biliary atresia screening. Pediatrics. 2009;123:1280-6.

24. Lampela H, Ritvanen A, Kosola S, Koivusalo A, Rintala R,

Jalanko H, et al. National centralization of biliary atresia

care to an assigned multidisciplinary team provides highquality outcomes. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2012;47:99-107.

25. McKiernan PJ, Baker AJ, Kelly DA. The frequency and

outcome of biliary atresia in the UK and Ireland. Lancet.

2000;355:25-9.

26. Whitington PF, Freese DK, Alonso EM, Schwarzenberg

SJ, Sharp HL. Clinical and biochemical findings in

progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis. J Pediatr

Gastroenterol Nutr. 1994;18:134-41.

27. Hsiao CH, Chang MH, Chen HL, Lee HC, Wu TC, Lin CC,

et al. Universal screening for biliary atresia using an infant

stool color card in Taiwan. Hepatology. 2008;47:1233-40.

28. Niedbala A, Lankford A, Boswell WC, Rittmeyer C.

Spontaneous perforation of the bile duct. Am Surg.

2000;66:1061-3.

29. Lee WS, Looi LM. Usefulness of a scoring system in the

interpretation of histology in neonatal cholestasis. World J

Gastroenterol. 2009;15:5326-33.

30. Singh R, Thapa BR, Kaur G, Prasad R. Biochemical and

molecular characterization of GALT gene from Indian

galactosemia patients: identification of 10 novel mutations

and their structural and functional implications. Clin Chim

Acta. 2012;414:191-6.

31. Singh R, Kaur G, Thapa BR, Prasad R, Kulkarni K. A case

of

classical

galactosemia:

identification

and

characterization of 3 distinct mutations in galactose-1phosphate uridyl transferase (GALT) gene in a single

family. Indian J Pediatr. 2011;78:874-6.

32. Bijarnia S, Puri RD, Ruel J, Gray GF, Jenkinson L, Verma

REFERENCES

1. Consensus report on neonatal cholestasis syndrome.

Pediatric Gastroenterology Subspecialty Chapter of Indian

Academy of Pediatrics. Indian Pediatr. 2000;37:845-51.

2. Yachha SK, Sharma A. Neonatal cholestasis in India.

Indian Pediatr. 2005;42:491-2.

3. Yachha SK. Cholestatic jaundice during infancy. Indian J

Gastroenterol. 2005;24:47-8.

4. Davis AR, Rosenthal P, Escobar GJ, Newman TB.

Interpreting conjugated bilirubin levels in newborns. J

Pediatr. 2011;158:562-5.

5. Moyer V, Freese DK, Whitington PF, Olson AD, Brewer F,

Colletti RB, et al. Guideline for the evaluation of

cholestatic jaundice in infants: recommendations of the

North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology,

Hepatology and Nutrition. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr.

2004;39:115-28.

6. Yachha SK, Khanduri A, Kumar M, Sikora SS, Saxena R,

Gupta RK, et al. Neonatal cholestasis syndrome: an

appraisal at a tertiary center. Indian Pediatr. 1996;33:72934.

7. Arora NK, Arora S, Ahuja A, Mathur P, Maheshwari M,

Das MK, et al. Alpha 1 antitrypsin deficiency in children

with chronic liver disease in North India. Indian Pediatr.

2010;47:1015-23.

8. Yachha SK, Sharma BC, Khanduri A, Srivastava A.

Current spectrum of hepatobiliary disorders in northern

India. Indian Pediatr. 1997;34:885-90.

9. Alagille D, Habib EC, Thomassin N. Latresie des voies

biliaires extrahepatiques permeables chez lenfant. J Par

Pediatr 1969:301-18.

10. Kamath BM, Spinner NB, Piccoli DA. Alagille Syndrome.

In: Suchy F, Sokol RJ, Balistreri WF, editors. Liver

Disease in Children. Third ed. New York: Cambridge

University Press; 2007. p. 326-45.

11. Mizuta K, Sanada Y, Wakiya T, Urahashi T, Umehara M,

Egami S, et al. Living-donor liver transplantation in 126

patients with biliary atresia: single-center experience.

Transplant Proc. 2010;42:4127-31.

12. Sanghai SR, Shah I, Bhatnagar S, Murthy A. Incidence and

prognostic factors associated with biliary atresia in

Western India. Ann Hepatol. 2009;8:120-2.

13. Ahmad M, Jan M, Ali W, Shabir ud d, Bashir C, Iqbal Q, et

al. Neonatal cholestasis in Kashmiri children. JK Pract.

2000;7:125-6.

14. Khalil S, Shah D, Faridi MM, Kumar A, Mishra K.

Prevalence and outcome of hepatobiliary dysfunction in

neonatal septicaemia. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr.

2012;54:218-22.

15. Poddar U, Thapa BR, Das A, Bhattacharya A, Rao KL,

Singh K. Neonatal cholestasis: differentiation of biliary

atresia from neonatal hepatitis in a developing country.

Acta Paediatr. 2009;98:1260-4.

INDIAN PEDIATRICS

209

VOLUME 51__MARCH 15, 2014

BHATIA, et al.

33.

34.

35.

36.

37.

38.

39.

MANAGEMENT OF NEONATAL CHOLESTASIS

IC. Tyrosinemia type Idiagnostic issues and prenatal

diagnosis. Indian J Pediatr. 2006;73:163-5.

Suchy FJ. Neonatal cholestasis. Pediatr Rev. 2004;25:38896.

Feranchak AP, Sokol RJ. Medical and nutritional

mManagement of cholestasis in infants and children. In:

Suchy FJ, Sokal RJ, Balistreri WF, editors. Liver Diseases

in Children. 3rd ed. New York: Cambridge University

Press; 2007. p. 190-231.

Venigalla S, Gourley GR. Neonatal cholestasis. Semin

Perinatol. 2004;28:348-55.

Sokol RJ, Shepherd RW, Superina R, Bezerra JA, Robuck

P, Hoofnagle JH. Screening and outcomes in biliary

atresia: summary of a National Institutes of Health

workshop. Hepatology. 2007;46:566-81.

Bassett MD, Murray KF. Biliary atresia: recent progress. J

Clin Gastroenterol. 2008;42:720-9.

Sharma D, Shah UH, Sibal A, Chowdhary SK.

Cholecystoappendicostomy for progressive familial

intrahepatic cholestasis. Indian Pediatr. 2010;47:626-8.

Bhatia V, Bavdekar A, Yachha SK. Management of acute

INDIAN PEDIATRICS

40.

41.

42.

43.

44.

210

liver failure in infants and children: Consensus statement of

the Pediatric Gastroenterology Chapter, Indian Academy

of Pediatrics. Indian Pediatr. 2013;50:477-82.

Poonacha P, Sibal A, Soin AS, Rajashekar MR,

Rajakumari DV. Indias first successful pediatric liver

transplant. Indian Pediatr. 2001;38:287-91.

Sibal A. Pediatric Liver transplantation in India: Past,

Present and future. 21th Annual Conference of Indian

National Association for Study of the Liver [INASL] 2013;

Hyderabad, India.

Utterson EC, Shepherd RW, Sokol RJ, Bucuvalas J, Magee

JC, McDiarmid SV, et al. Biliary Atresia: Clinical Profiles,

Risk Factors, and Outcomes of 755 Patients Listed for

Liver Transplantation. J Pediatr. 2005;147:180-5.

Wang SH, Chen CL, Concejero A, Wang CC, Lin CC, Liu

YW, et al. Living donor liver transplantation for biliary

atresia. Chang Gung Med J. 2007;30:103-8.

Kaur S, Wadhwa N, Sibal A, Jerath N, Sasturkar S.

Outcome of live donor liver transplantation in Indian

children with bodyweight 7.5 kg. Indian Pediatr.

2011;48:51-4.

VOLUME 51__MARCH 15, 2014

You might also like

- Journal of Pediatric Surgery: Ibrahim UygunDocument4 pagesJournal of Pediatric Surgery: Ibrahim UygunNur Ainatun NadrahNo ratings yet

- Journal of Pediatric Surgery: Shawn T. Liechty, Douglas C. Barnhart, Jordan T. Huber, Sarah Zobell, Michael D. RollinsDocument4 pagesJournal of Pediatric Surgery: Shawn T. Liechty, Douglas C. Barnhart, Jordan T. Huber, Sarah Zobell, Michael D. RollinssuperwymNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S002234681500617X MainDocument7 pages1 s2.0 S002234681500617X MainNur Ainatun NadrahNo ratings yet

- Journal of Pediatric Surgery: Shawn T. Liechty, Douglas C. Barnhart, Jordan T. Huber, Sarah Zobell, Michael D. RollinsDocument4 pagesJournal of Pediatric Surgery: Shawn T. Liechty, Douglas C. Barnhart, Jordan T. Huber, Sarah Zobell, Michael D. RollinssuperwymNo ratings yet

- Journal of Pediatric SurgeryDocument6 pagesJournal of Pediatric SurgeryNur Ainatun NadrahNo ratings yet

- Journal of Pediatric SurgeryDocument6 pagesJournal of Pediatric SurgeryNur Ainatun NadrahNo ratings yet

- Journal of Pediatric Surgery: Indepent Review ArticlesDocument4 pagesJournal of Pediatric Surgery: Indepent Review ArticlesNur Ainatun NadrahNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S002234681500617X MainDocument7 pages1 s2.0 S002234681500617X MainNur Ainatun NadrahNo ratings yet

- Journal of Pediatric SurgeryDocument5 pagesJournal of Pediatric SurgeryNur Ainatun NadrahNo ratings yet

- Journal of Pediatric SurgeryDocument3 pagesJournal of Pediatric SurgeryNur Ainatun NadrahNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0022346815006351 MainDocument6 pages1 s2.0 S0022346815006351 MainNur Ainatun NadrahNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0022346815006399 MainDocument6 pages1 s2.0 S0022346815006399 MainNur Ainatun NadrahNo ratings yet

- Journal of Pediatric Surgery: Contents Lists Available atDocument6 pagesJournal of Pediatric Surgery: Contents Lists Available atNur Ainatun NadrahNo ratings yet

- Journal of Pediatric SurgeryDocument4 pagesJournal of Pediatric SurgeryNur Ainatun NadrahNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0022346815007198 MainDocument2 pages1 s2.0 S0022346815007198 MainNur Ainatun NadrahNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0022346815006417 MainDocument6 pages1 s2.0 S0022346815006417 MainNur Ainatun NadrahNo ratings yet

- Journal of Pediatric SurgeryDocument4 pagesJournal of Pediatric SurgeryNur Ainatun NadrahNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0022346815006478 MainDocument6 pages1 s2.0 S0022346815006478 MainNur Ainatun NadrahNo ratings yet

- Paediatric Cholestatic Liver Disease: Diagnosis, Assessment of Disease Progression and Mechanisms of FibrogenesisDocument16 pagesPaediatric Cholestatic Liver Disease: Diagnosis, Assessment of Disease Progression and Mechanisms of FibrogenesiswintannNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0022346815006430 MainDocument5 pages1 s2.0 S0022346815006430 MainNur Ainatun NadrahNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0022346815006454 MainDocument5 pages1 s2.0 S0022346815006454 MainNur Ainatun NadrahNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S1063458415013187 MainDocument13 pages1 s2.0 S1063458415013187 MainNur Ainatun NadrahNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0022346815006466 MainDocument5 pages1 s2.0 S0022346815006466 MainNur Ainatun NadrahNo ratings yet

- 4200 p167 PDFDocument26 pages4200 p167 PDFNur Ainatun NadrahNo ratings yet

- GH 04 691Document3 pagesGH 04 691Nur Ainatun NadrahNo ratings yet

- Fetal Growth and Body Proportion in Preeclampsia.26Document9 pagesFetal Growth and Body Proportion in Preeclampsia.26Nur Ainatun NadrahNo ratings yet

- 2248Document14 pages2248Nur Ainatun NadrahNo ratings yet

- Health Problems and Health Seeking Behaviour of Hospital Cleaners in A Tertiary Health Facility in South West NigeriaDocument6 pagesHealth Problems and Health Seeking Behaviour of Hospital Cleaners in A Tertiary Health Facility in South West NigeriaNur Ainatun NadrahNo ratings yet

- Apert Syndrome: Anaesthetic Concerns and Challenges: Egyptian Journal of AnaesthesiaDocument3 pagesApert Syndrome: Anaesthetic Concerns and Challenges: Egyptian Journal of AnaesthesiaNur Ainatun NadrahNo ratings yet

- G-Tze Et Al-2015-Frontiers in PediatricsDocument32 pagesG-Tze Et Al-2015-Frontiers in PediatricsNur Ainatun NadrahNo ratings yet

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Orthobullets Foot and AnkleDocument88 pagesOrthobullets Foot and AnkleStevent Richardo100% (1)

- Bahasa InggrisDocument6 pagesBahasa InggrisSofi SusantoNo ratings yet

- Adult Early Warning Score Observation Chart For Cardiothoracic UnitDocument1 pageAdult Early Warning Score Observation Chart For Cardiothoracic UnitalexipsNo ratings yet

- DOPR Vision 2030Document36 pagesDOPR Vision 2030Hendi HendriansyahNo ratings yet

- MBF90324234Document407 pagesMBF90324234Emad Mergan100% (1)

- Satyug Darshan Vidalaya1Document30 pagesSatyug Darshan Vidalaya1Naina GuptaNo ratings yet

- Fertilization Reflection PaperDocument2 pagesFertilization Reflection PaperCrisandro Allen Lazo100% (2)

- Development of The Vertebrate EyeDocument5 pagesDevelopment of The Vertebrate Eyezari_pak2010No ratings yet

- Eaves Nickolas A 201211 MASc ThesisDocument69 pagesEaves Nickolas A 201211 MASc Thesisrajeev50588No ratings yet

- Medical FlyerDocument2 pagesMedical FlyerThana PalNo ratings yet

- Electronic Physician (ISSN: 200 08-5842)Document10 pagesElectronic Physician (ISSN: 200 08-5842)Sapi KemploNo ratings yet

- Carbon Monoxide PoisoningDocument31 pagesCarbon Monoxide PoisoningDheerajNo ratings yet

- CATHETERIZATIONDocument3 pagesCATHETERIZATIONrnrmmanphdNo ratings yet

- Aldrine Ilustricimo VS Nyk Fil Sjip Management IncDocument11 pagesAldrine Ilustricimo VS Nyk Fil Sjip Management Inckristel jane caldozaNo ratings yet

- Standardised Nomenclature of Animal Parasitic Diseases (Snopad)Document67 pagesStandardised Nomenclature of Animal Parasitic Diseases (Snopad)Pwaveno BamaiyiNo ratings yet

- Sample Chapter of Assessment Made Incredibly Easy! 1st UK EditionDocument28 pagesSample Chapter of Assessment Made Incredibly Easy! 1st UK EditionLippincott Williams and Wilkins- Europe100% (1)

- Cellular Aberration Acute Biologic Crisis 100 Items - EditedDocument8 pagesCellular Aberration Acute Biologic Crisis 100 Items - EditedSherlyn PedidaNo ratings yet

- Week 6 Nursing Care of The Family With Reproductive DisordersDocument27 pagesWeek 6 Nursing Care of The Family With Reproductive DisordersStefhanie Mae LazaroNo ratings yet

- Aynı MakaleDocument95 pagesAynı MakalesalihcikkNo ratings yet

- 10a General Pest Control Study GuideDocument128 pages10a General Pest Control Study GuideRomeo Baoson100% (1)

- Bipolar Disorder - A Cognitive Therapy Appr - Cory F. NewmanDocument283 pagesBipolar Disorder - A Cognitive Therapy Appr - Cory F. NewmanAlex P100% (1)

- ETT IntubationDocument27 pagesETT IntubationGilbert Sterling Octavius100% (1)

- Towards A Sociology of Health Discourse in AfricaDocument172 pagesTowards A Sociology of Health Discourse in AfricaDavid Polowiski100% (2)

- ANIOSPRAY QUICK-Fiche Technique-00000-ENDocument2 pagesANIOSPRAY QUICK-Fiche Technique-00000-ENGustea Stefan AlinNo ratings yet

- Growth Comparison in Children With and Without Food Allergies in 2 Different Demographic PopulationsDocument7 pagesGrowth Comparison in Children With and Without Food Allergies in 2 Different Demographic PopulationsMaria Agustina Sulistyo WulandariNo ratings yet

- Thesis On Hypertension in PregnancyDocument7 pagesThesis On Hypertension in Pregnancydwt29yrp100% (2)

- Nursing Management of HypertensionDocument152 pagesNursing Management of HypertensionEnfermeriaAncam100% (3)

- Environmental Studies-FIRST UNIT-vkmDocument59 pagesEnvironmental Studies-FIRST UNIT-vkmRandomNo ratings yet

- National Geographic USA - January 2016Document148 pagesNational Geographic USA - January 2016stamenkovskib100% (4)

- Geria NCPDocument4 pagesGeria NCPBrylle CapiliNo ratings yet