Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Introduction To Pragmatics

Uploaded by

Martina PiccoliOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Introduction To Pragmatics

Uploaded by

Martina PiccoliCopyright:

Available Formats

Introduction to pragmatics

Chris Potts, Ling 130a/230a: Introduction to semantics and pragmatics, Winter 2015

Feb 3

Layers of pragmatic enrichment

Pragmatics is the study of the ways we enrich the conventionalized meanings of the things we say

and hear into their fuller intended meanings. In class, well focus on the principles that govern this

enrichment process, with special emphasis on the extent to which it is systematic and universal.

1.1

Levinsons analogy

We interpret this sketch instantly and effortlessly as a gathering

of people before a structure, probably a gateway; the people are

listening to a single declaiming figure in the center. [. . . ] But all

this is a miracle, for there is little detailed information in the lines

or shading (such as there is). Every line is a mere suggestion [. . . ].

So here is the miracle: from a merest, sketchiest squiggle of lines,

you and I converge to find adumbration of a coherent scene [. . . ].

The problem of utterance interpretation is not dissimilar to this

visual miracle. An utterance is not, as it were, a verdical model or

snapshot of the scene it describes [. . . ]. Rather, an utterance is

just as sketchy as the Rembrandt drawing. (Levinson 2000:24)

The responses are a mix of things that all humans recover and things that require special cultural

knowledge (to some degree). Linguistic enrichment also varies along these dimensions.1

1.2

An approach to variation

i. One of the fundamental claims of pragmatic theory is that most, perhaps all, pragmatic

enrichment is the product of basic principles of rationality. (Well discuss what this means

extensively.)

ii. This seems to suggest the absurdly incorrect conclusion that pragmatic enrichment is the

same the world over.

iii. We propose to resolve this tension as follows: the basic pragmatic principles (principles of

rational communication) are the same the world over. But just as our differing backgrounds

lead us to extract different information from the Rembrandt sketch, so too can they lead us

to different pragmatic enrichments.

1

Its significant that computers can read barcodes but they flounder with images like this. If it werent for the

centrality of pragmatics, wed have talking computers by now.

Ling 130a/230a, Stanford (Potts)

This lecture Well first get a better grip on what pragmatic enrichment is, and then well explore

its importance for communication and for understanding linguistic variation.

1.3

A bit of history

In the early 1960s, Chomsky showed us how to give compact, general specifications of natural language syntax.

In the late 1960s, philosopher and linguist H. Paul Grice had

the inspired idea to do the same for (rational) social interactions.

Bach (1994) on the lead-up to Grice (see also Chapman 2005; Potts 2006):

There was a time when philosophy of language was concerned less with language and

its use than with meanings and propositions. [. . . ] It is no exaggeration to say that

such philosophers as Frege, Russell, and the early Wittgenstein paid only lip service to

natural languages, for they were more interested in deep and still daunting problems

about representation, which they hoped to solve by studying the properties of ideal

(logically perfect) languages, where forms of sentences mirror the forms of what

sentences symbolize. [. . . ] Austin and the later Wittgenstein changed all that. [. . . ]

[T]he Wittgenstein of the Philosophical Investigations, rebelling against his former self,

came to think of language not primarily as a system of representation but as a vehicle

for all sorts of social activity. Dont ask for the meaning, ask for the use, he advised.

Grices Logic and conversation Grice (1975) is a defining moment in pragmatic theory. It

strikes a balance between the two extremes described above, and it outlines a general theory of

how to allow semantics and pragmatics to work together to produce linguistic meaning.

Ling 130a/230a, Stanford (Potts)

Some pragmatic phenomena

i. Quantifier domains Why does everyone so rarely quantify over everyone?

The everything bagel

@James_Kpatrick: These two books

contain the sum total of all human

knowledge

@patrickmarkryan: Come on, Everything

Bagels, who you tryin to fool? You got

like 6 seasonings on there. Thats a lot,

but it aint everything.

@dwineman: Last time I had an everything bagel I got poppy seeds, Mira

Sorvino, and Hegels Phenomenology of

Spirit all over my shirt.

In the know deletion

No one goes there anymore its too crowded. (Yogi Berra)

ii. Modality: In my elementary school, students were often admonished for saying Can I go to

the bathroom rather than May I . . . . I consider this an injustice; can has both ability and

deontic (permission-oriented) readings, and the teachers knew which we meant!

iii. Scalar inferences: Why do some and most tend to exclude all? Why does three tend to mean

exactly three? Why does few tend to exclude no?

iv. Focus effects: How does Well, Ellen didnt READ the book come to suggest (implicate) that

Ellen did something else with the book? (Compare, ELLEN didnt read the book; see Kratzer

1991; Bring 1999.)

Francis Ford Coppolas The Conversation

The entire movie turns on whether the man being recorded said

Hed kill us if he got the chance.

or

HEd kill US if he got the chance.

Harry Caul is tormented by the question of which he hears on the recording.

v. Indexicals: What do I and you and here refer to? How do they get their referents (Kaplan

1999; Nunberg 1993; Kratzer 2009)?

Pragmatics

Ling 130a/230a, Stanford (Potts)

Ling 130a/230a, Stanford (Potts)

v. Indexicals: What do I and you and here refer to? How do they get their referents (Kaplan

1999; Nunberg 1993; Kratzer 2009)?

vi. Belief reports: Is it false or misleading to say that Lois Lane believes Superman is a reporter?

orreports:

why notIs(Berg

1988)?

vi. Why

Belief

it false

or misleading to say that Lois Lane believes Superman is a reporter?

Why or why not (Berg 1988)?

vii. Gradable adjectives: How can That mouse is tall be true and That elephant is tall be false in

vii. aGradable

Howthe

canelephant

That mouse

tallmouse

be trueare

and1 That

elephant

situationadjectives:

in which both

andisthe

meter

tall? is tall be false in

a situation in which both the elephant and the mouse are 1 meter tall?

viii. Intrasentential anaphora: Why is it so hard to interpret he as coreferential with Eddie in He

viii. Intrasentential anaphora: Why is it so hard to interpret he as coreferential with Eddie in He

believes that Eddie deserves a prize?

believes that Eddie deserves a prize?

how big is the contextually restricted

domain of students?

whats the additional contextual

restriction?

false for most students?

whos the speaker?

Many students met with me yesterday.

but perhaps many met with the

speaker at other times?

whats the time of utterance?

2 The Gricean maxims of conversation

3 The Gricean maxims of conversation

Grices maxims are the backbone of his pragmatic theory. They are not scientific generalizations in

Grices

maxims

theare

backbone

of contractual

his pragmatic

theory. They

areofnot

generalizations

the usual

sense.are

They

more like

obligations

or laws

thescientific

land. If you

break one, in

the

They

like interesting

contractualconsequences.

obligations or laws of the land. If you break one,

youusual

dontsense.

falsify it.

Youare

justmore

generate

you dont falsify it. You just generate interesting consequences.

The cooperative principle (a super-maxim) Make your contribution as is required, when

it is cooperative

required, by the

conversation

in which you are

engaged.

The

principle

(a super-maxim)

Make

your contribution as is required, when

is required,

by the conversation

whichtoyou

are engaged.

itQuality

Contribute

only what youinknow

be true.

Do not say false things. Do not say

things for Contribute

which you lack

Quality

onlyevidence.

what you know to be true. Do not say false things. Do not say

things for which you lack evidence.

Quantity Make your contribution as informative as is required. Do not say more than is

required. Make your contribution as informative as is required. Do not say more than is

Quantity

required.

Relation (Relevance)

Make your contribution relevant.

Relation (Relevance) Make your contribution relevant.

Manner (i) Avoid obscurity; (ii) avoid ambiguity; (iii) be brief; (iv) be orderly.

Manner (i) Avoid obscurity; (ii) avoid ambiguity; (iii) be brief; (iv) be orderly.

We dont satisfy all these demands all of the time. Grice identified three ways in which this can

happen:

we might

just opt-out

of one

or the

more

maxims,

might encounter

a hopeless

We

dont satisfy

all these

demands

all of

time.

Gricewe

identified

three ways

in which clash

this can

between

two

or

more

maxims,

or

we

might

flout

(blatantly

fail

to

fulfill)

one

or

more

maxims.

happen: we might just opt-out of one or more maxims, we might encounter a hopeless clash

between two or more maxims, or we might flout (blatantly fail to fulfill) one or more maxims.

4

Ling 130a/230a, Stanford (Potts)

3.1

Quality: Be truthful!

Cooperative speakers obey this at all costs. If we get too lax on quality, what we say is untrustworthy, and communication breaks down. However, we are allowed to be a little lax (Joshi 1982;

Davis et al. 2007).

Flouting quality (perhaps)

What are your quality standards?

Note: you might be a brain in a vat.

(1)

Yeah, and Im a monkeys uncle!

(2)

Well, thats just great!

(3)

Youll win the Nobel prize in your dreams!

(4)

Metaphor (Kao et al. 2014a)

(5)

Hyperbole (Kao et al. 2014b)

The liar and the bullshitter (Frankfurt 1986)

The liar cares about the truth. He intends to convey the opposite.

The bullshitter says things for which he has limited or no evidence, but not with

the aim of deceiving. He might hope that what he is saying is true. Its just that he

is not justified in his assertions (and doesnt inform you of this fact).

In bull sessions, the pressures of quality are somewhat relaxed.

3.2

Quantity: Be informative!

Quantity asks speakers to strike a balance between providing new information and providing too

much new information (Horn 1984; Geurts 2011).

Interactions (clashes) with quality

(6)

Sues work was

(7)

I have three fingers.

outstanding

excellent

good.

satisfactory

possibly ruled out by quality!

(= as high as the speaker can go, by quantity

Ling 130a/230a, Stanford (Potts)

Interactions (clashes) with politeness

(8)

In the context of a recommendation letter:

We are pleased to say that Landry is a former colleague of ours. All in all, we cannot say

enough good things about him. He has excellent penmanship, and he always arrives to

meetings on time. You will be fortunate indeed if you can get him to work for you.

Flouting quantity with tautologies Grice maintained that tautologies are, strictly speaking, extreme violations of quantity, since they cant help but be true. Do you agree with the assessment?

(9)

Opting out of quantity

(11)

(10)

War is war.

Boys will be boys.

Some conventions:

No comment.

(12)

Mistakes were made.

(13)

I plead the fifth.

Literal interpretations

Kyle:

Marge

Can you pass the salt?

Yes. (without passing the salt)

Lets find (i) a context in which Marges reply is pragmatically odd (uncooperative) and

(ii) a context in which it is natural.

Examples from the group work?

3.3

Relevance: Be relevant!

Relevant to what? Its useful to assume that speakers are working to address some question or

questions. These might be highly abstract questions that they cant really articulate, but they are

nonetheless present, and were expected to offer information that helps answer them (Ginzburg

1996; Roberts 1996; Beaver & Clark 2008).

A fundamental pressure The pressure of relevance is so strong and so important that, if you try

to break free of it, people will still assume you are abiding by it and so will struggle to make what

you say relevant somehow to the topic at hand.

Overlap with quantity Grices quantity mentions whats required. In practice, this means that

it overlaps a lot with relevance. One approach is to simplify quantity so that it simply says Be

informative, with excesses handled by relevance.

Flouting relevance

(14)

Suppose that A and B are talking about a mutual friend, C, who is now working in a bank.

A asks B how C is getting on in his job, and B replies, Oh quite well, I think; he likes his

colleagues, and he hasnt been to prison yet. (from Logic and conversation)

6

Ling 130a/230a, Stanford (Potts)

Interactions (clashes) with quality (or politeness, or not . . . )

(15)

From the movie When Harry Met Sally

Harry:

Jess:

Harry:

Jess:

Look, if you had asked me what does she look like and I said, she has a

good personality, that means shes not attractive. But just because I happen

to mention that she has a good personality, she could be either. She could be

attractive with a good personality, or not attractive with a good personality.

So which one is she?

Attractive.

But not beautiful, right?

Opting out (or attempting to opt out) of relevance

(16)

A:

B:

How do I put this table together?

Very carefully.

Examples from the group work?

3.4

Manner: Be clear and concise!

Manner regulates the forms we use (McCawley 1978; Horn 1984; Blutner 2000). The other maxims concern the content of those forms.

Inherent conflict The submaxims of manner are inherently in conflict. For instance, short utterances tend to be ambiguous, and avoiding ambiguities often requires long sentences.

A related heuristic (Levinson) Normal events are reported with normal language. Unusual

events are reported with unusual language.

Flouting or opting out of Avoid obscurity

(Examples from the group work?)

Avoid ambiguity This can be hard for speakers to do, and the result is often hilarious (as in those

books of headlines like JUVENILE COURT TO TRY SHOOTING DEFENDANT).

Flouting Be brief (Examples from the group work?)

Being orderly with and

(17)

a.

I got into bed and brushed my teeth.

b.

I brushed my teeth and got into bed.

c.

I got into bed and brushed my teeth but not in that order!

d.

I took pragmatics and I took syntax.

e.

Germany is in Europe and Canada is in North America.

7

Ling 130a/230a, Stanford (Potts)

3.5

Politeness: The missing maxim

The pressure to be polite can be powerful in some situations (and in some cultures), it can

overwhelm all the other pragmatic pressures, resulting in utterances that are overly long (violating

manner) and under-informative (violating quantity).

(18)

Have you ever said

a.

b.

I think this is the right way when you knew it was? You might have been trying to help your addressee save face by minimizing the difference in your knowledge/expertise.

Sorry to bother you, but might you have the time to. . . when you really just wanted

to issue a request? If so, you might have been trying (or acting as if you were trying)

to provide or addressee with a graceful way decline your request.

This behavior arises from more fundamental social pressures concerning our desire to save face

(avoid awkward embarassment or worse). For discussion, see Lakoff 1973; Brown & Levinson

1987, 1978; Watts 2003.

References

Bach, Kent. 1994. Meaning, speech acts, and communication. In Robert Harnish (ed.), Basic topics in the philosophy of language, 320. Englewood

Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Beaver, David I. & Brady Zack Clark. 2008. Sense and sensitivity: How focus determines meaning. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

Berg, Jonathan. 1988. The pragmatics of substitutivity. Linguistics and Philosophy 11(3). 355370.

Blutner, Reinhard. 2000. Some aspects of optimality in natural language interpretation. Journal of Semantics 17(3). 189216.

Brown, Penelope & Stephen C. Levinson. 1978. Universals in language use: Politeness phenomena. In Esther N. Goody (ed.), Questions and

politeness: Strategies in social interaction, 56311. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Brown, Penelope & Stephen C. Levinson. 1987. Politeness: Some universals in language use. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bring, Daniel. 1999. Topic. In Peter Bosch & Rob van der Sandt (eds.), Focus linguistic, cognitive, and computational perspectives, 142165.

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Chapman, Siobhan. 2005. Paul Grice: Philosopher and linguist. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan.

Davis, Christopher, Christopher Potts & Margaret Speas. 2007. The pragmatic values of evidential sentences. In Masayuki Gibson & Tova Friedman

(eds.), Proceedings of Semantics and Linguistic Theory 17, 7188. Ithaca, NY: CLC Publications.

Frankfurt, Harry G. 1986. On bullshit. Raritan 6(2). 81100. Reprinted in Frankfurt (1988), 117133.

Frankfurt, Harry G. 1988. The importance of what we care about. Cambridge University Press.

Geurts, Bart. 2011. Quantity implicatures. Cambridge University Press.

Ginzburg, Jonathan. 1996. Interrogatives: Questions, facts, and dialogue. In Shalom Lappin (ed.), The handbook of contemporary semantic theory,

385422. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers.

Grice, H. Paul. 1975. Logic and conversation. In Peter Cole & Jerry Morgan (eds.), Syntax and semantics, vol. 3: Speech Acts, 4358. New York:

Academic Press.

Horn, Laurence R. 1984. Toward a new taxonomy for pragmatic inference: Q-based and R-based implicature. In Deborah Schiffrin (ed.), Meaning,

form, and use in context: Linguistic applications, 1142. Washington, D.C.: Georgetown University Press.

Joshi, Aravind K. 1982. Mutual belief in question answering systems. In Neil S. Smith (ed.), Mutual knowledge, 181197. London: Academic Press.

Kao, Justine T., Leon Bergen & Noah D. Goodman. 2014a. Formalizing the pragmatics of metaphor understanding. In Proceedings of the 36th annual

meeting of the cognitive science society, 719724. Wheat Ridge, CO: Cognitive Science Society.

Kao, Justine T., Jean Wu & Noah D. Goodman. 2014b. Halo, hyperbole, and the pragmatic interpretation of numbers. Ms., Stanford Psychology.

Kaplan, David. 1999. What is meaning? Explorations in the theory of Meaning as Use. Brief version draft 1. Ms., UCLA.

Kratzer, Angelika. 1991. The representation of focus. In Arnim von Stechow & Dieter Wunderlich (eds.), Semantik/semantics: An international

handbook of contemporary research, 825834. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.

Kratzer, Angelika. 2009. Making a pronoun: Fake indexicals as windows into the properties of pronouns. Linguistic Inquiry 40(2). 187237.

Lakoff, Robin. 1973. The logic of politeness; or, minding your Ps and Qs. In Claudia Corum, T. Cedric Smith-Stark & Ann Weiser (eds.), Proceedings

of the 9th meeting of the Chicago Linguistic Society, 292305. Chicago: Chicago Linguistic Society.

Levinson, Stephen C. 2000. Presumptive meanings: The theory of generalized conversational implicature. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

McCawley, James D. 1978. Conversational implicature and the lexicon. In Peter Cole (ed.), Syntax and semantics, vol. 7: Pragmatics, 245259. New

York: Academic Press.

Nunberg, Geoffrey. 1993. Indexicality and deixis. Linguistics and Philosophy 16(1). 143.

Potts, Christopher. 2006. Review of Siobhan Chapman, Paul Grice: Philosopher and Linguist. Mind 115(459). 743747.

Roberts, Craige. 1996. Information structure: Towards an integrated formal theory of pragmatics. In Jae Hak Yoon & Andreas Kathol (eds.), OSU

working papers in linguistics, vol. 49: Papers in Semantics, 91136. Columbus, OH: The Ohio State University Department of Linguistics. Revised

1998.

Watts, Richard J. 2003. Politeness. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Wittgenstein, Ludwig. 1953. Philosophical investigations. New York: The MacMillan Company. Translated by G. E. M. Anscombe.

You might also like

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- My ResumeDocument2 pagesMy ResumeSimon MuiruriNo ratings yet

- Sample Web/Graphic Design QuestionnaireDocument7 pagesSample Web/Graphic Design QuestionnaireTori Walker100% (2)

- Co-Teaching StrategiesDocument2 pagesCo-Teaching Strategiesapi-317273644100% (1)

- SLAC on Test ConstructionDocument7 pagesSLAC on Test ConstructionLEILANI PELISIGASNo ratings yet

- Date: I. Objectives: Date: I. Objectives:: 1. Pre Listening ActivitiesDocument6 pagesDate: I. Objectives: Date: I. Objectives:: 1. Pre Listening ActivitiesNarito ArnelNo ratings yet

- Paltridge Discourse Analysis An Introduction PDFDocument117 pagesPaltridge Discourse Analysis An Introduction PDFMartina Piccoli22% (9)

- Cooperative Principle - Tesi Su Speech ActDocument30 pagesCooperative Principle - Tesi Su Speech ActMartina PiccoliNo ratings yet

- Grice Maxims + Audiovisual TranslationDocument12 pagesGrice Maxims + Audiovisual TranslationMartina Piccoli100% (1)

- Cooperative Principle - Tesi Su Speech ActDocument30 pagesCooperative Principle - Tesi Su Speech ActMartina PiccoliNo ratings yet

- Grice Maxims + Audiovisual TranslationDocument12 pagesGrice Maxims + Audiovisual TranslationMartina Piccoli100% (1)

- Allwood. A Bird's Eye View of PragmaticsDocument16 pagesAllwood. A Bird's Eye View of PragmaticsMartina PiccoliNo ratings yet

- Allwood. Linguistic Communication As Action and CooperationDocument196 pagesAllwood. Linguistic Communication As Action and CooperationMartina PiccoliNo ratings yet

- DLL Health 9 & 10Document6 pagesDLL Health 9 & 10Gladys GutierrezNo ratings yet

- Example of Lesson PlanDocument5 pagesExample of Lesson Planapi-288141119No ratings yet

- 4SP1 IG Spanish Grade DescriptorDocument7 pages4SP1 IG Spanish Grade DescriptorOliver ZingNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1Document21 pagesChapter 1anushka bhandareNo ratings yet

- Translating Cultural Identity in PoetryDocument15 pagesTranslating Cultural Identity in PoetryZubaida MhdNo ratings yet

- ComputerDocument5 pagesComputerparul sahuNo ratings yet

- Ict9 Group5 WrittenreportDocument2 pagesIct9 Group5 Writtenreportapi-293116810No ratings yet

- Lesson 44 - Place Value and Value of A Digit in A Given Decimal Number Through HundredthsDocument54 pagesLesson 44 - Place Value and Value of A Digit in A Given Decimal Number Through HundredthsDina GarganeraNo ratings yet

- Santana Et Al How To Practice Person Centred CareDocument12 pagesSantana Et Al How To Practice Person Centred CareShita DewiNo ratings yet

- Passed 5203-13-21MELCS Baguio Examining Oral Communicative ActivitiesDocument16 pagesPassed 5203-13-21MELCS Baguio Examining Oral Communicative ActivitiesMai Mai ResmaNo ratings yet

- AEVN Mission, Vision and MetricsDocument3 pagesAEVN Mission, Vision and MetricsAnasAhmedNo ratings yet

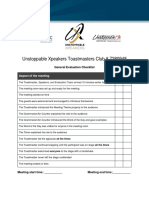

- Unstoppable Xpeakers Toastmasters Club EvaluationDocument3 pagesUnstoppable Xpeakers Toastmasters Club EvaluationJerry GreyNo ratings yet

- Tel Convo 1Document12 pagesTel Convo 1ABNo ratings yet

- Teaching Numeracy Through PlayDocument4 pagesTeaching Numeracy Through Playpianoman3_1417750No ratings yet

- English Class Rubric: Creativity in The Developed ActivitiesDocument2 pagesEnglish Class Rubric: Creativity in The Developed Activitiesxbox veraNo ratings yet

- Pervasive Developmental DisordersDocument11 pagesPervasive Developmental Disordersapi-3797941No ratings yet

- 2 Pratik Akhouri 22125740116Document4 pages2 Pratik Akhouri 22125740116Pratik AKhouriNo ratings yet

- Resume-Njemile PhillipDocument1 pageResume-Njemile Phillipapi-314917166No ratings yet

- The Effectiveness of Using Reader Response Approach in the ClassroomDocument4 pagesThe Effectiveness of Using Reader Response Approach in the ClassroomCikika100% (1)

- Tiered Lesson Plan WordDocument11 pagesTiered Lesson Plan Wordapi-354986063No ratings yet

- Numbering, EgyptDocument21 pagesNumbering, EgyptMohamed HusseinNo ratings yet

- p1 Dennis Cisco Packet Tracer 6.0.1Document26 pagesp1 Dennis Cisco Packet Tracer 6.0.1Trieu HuynhNo ratings yet

- Merger CommunicationDocument4 pagesMerger CommunicationAiman KirmaniNo ratings yet

- Assessing SpeakingDocument4 pagesAssessing SpeakingLightman_2004No ratings yet

- Communication in Multicultural Setting Essay - CoDocument2 pagesCommunication in Multicultural Setting Essay - CoCharlene Jean CoNo ratings yet