Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Abstract: Assimilative Rhetorics (Reflections Journal)

Uploaded by

aathonCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Abstract: Assimilative Rhetorics (Reflections Journal)

Uploaded by

aathonCopyright:

Available Formats

Amanda Athon,

Governors State

University

Assimilative Rhetorics

in 19th Century African

American Literacy

Manuals

Near the end of the 19th century, literacy manuals were

marketed to African Americans who sought to improve

their reading and writing skills outside of a traditional

classroom setting. I argue these texts had a worthwhile

goal of providing literacy instruction for learners, but they

were problematic in that they also served as a source for

assimilation into the dominant white culture. Via archival

research methods, I examine three of these manuals to discuss

how they taught literacy in addition to assimilating students

regarding family, politics, and religiona marked difference

from more traditional literacy instruction in the classroom.

The lessons represented the idea that discrimination was

not necessarily a problem caused by whites but the result

of a moral deficit on the part of African Americans. One

selection, Politics, published in Halls Moral and Mental

Capsule (1905), edited by Josie Hall, an African American

teacher, instructs, I think it would have been better far/If

the Negro had let politics alone/For the first thing he needed

was a home/An education and clothes (173). Another text

Sparkling Gems of Race Knowledge (1897), written and

published solely by James T. Haley, an African American

publisher, seems to be the exception, emphasizing a sense of

community through point-counterpoints on language used

to reference African Americans. These texts raise questions

of how writing instruction past and present may assimilate

students through the complicated idea of bettering oneself

through education. I conclude that the texts represent a still-

41

Reflections | Volume 15.1, Fall 2015

present paradox in education; the social advantages students seek are often unattainable

without some adoption of dominant social mores, even though it may unknowingly imply a

students own cultural identity is somehow deficient.

igher education is often promoted as a way of bettering

oneselfand undoubtedly, it is beneficial for students.

Education may also be seen as a type of activism because

it provides class mobility and economic opportunity. In the United

States, this linking of activism and bettering through education

originated in post-slavery 19th century, when education began to be

seen as a means of social advantage and an act of refinement, as

Shirley Wilson Logan notes in her book Liberating Language. Those

who provided the education were part of an upper class that the

learners sought to join. This created a rhetoric of assimilation where

the transfer of both knowledge and social norms from one dominant

class to another class could assist in creating social equality. This

rhetoric is perhaps best seen through textbooks printed in this postslavery era. During this time period, self-education manuals similar

to textbooks were marketed toward African Americans seeking an

education outside of a traditional classroom setting. Logan asserts

that these textswhile edited by African Americanswere compiled

of selections written by white authors (55), creating a disconnect

between author and audience. These texts, then, were not only a

means of private learning but also a source for assimilation into the

dominant white culture. Here I examine three African American selfeducation manuals to discuss how such artifacts instructed readers

on how to behave on such issues as family, politics, and religion.

The texts, Halls Moral and Mental Capsule for the Economic and

Domestic Life of the Negro, as a Solution of the Race Problem (1905);

The College of Life or Practical Self Educator: A Manual of Self

Improvement for the Colored Race (1896); and Sparkling Gems of Race

Knowledge Worth Reading: A Compendium of Valuable Information and

Wise Suggestions that Will Inspire Noble Effort at the Hands of Every

Race-Loving Man, Woman, and Child (1897); provide an overview of

the types of educational manuals available. Although these manuals

cannot represent every reader published during the late nineteenthcentury, they give current readers a sense of the educational and

social values of the time period, just as our modern educational

42

You might also like

- Fostering Access Through Universal Design: Dr. Amanda Athon Governors State University Aathon@Govst - EduDocument6 pagesFostering Access Through Universal Design: Dr. Amanda Athon Governors State University Aathon@Govst - EduaathonNo ratings yet

- SMHEC Presentation Athon HandoutDocument1 pageSMHEC Presentation Athon HandoutaathonNo ratings yet

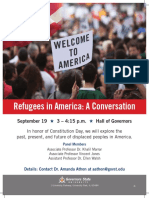

- CAS Refugee Talk Flyer 0816Document1 pageCAS Refugee Talk Flyer 0816aathonNo ratings yet

- Fostering Language Diversity Through Classroom-Based Assessment PracticesDocument2 pagesFostering Language Diversity Through Classroom-Based Assessment PracticesaathonNo ratings yet

- Accessible Assignment SheetDocument2 pagesAccessible Assignment SheetaathonNo ratings yet

- CWHandout RevDocument2 pagesCWHandout RevaathonNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5783)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Chandu RESUMEDocument2 pagesChandu RESUMEvijay_srivatsaNo ratings yet

- Dos and Don'ts of Tutoring TipsDocument4 pagesDos and Don'ts of Tutoring TipsTien Thanh Thuy NguyenNo ratings yet

- OUTLINEDocument6 pagesOUTLINERuthie PatootieNo ratings yet

- Research Proposal DraftDocument27 pagesResearch Proposal DraftSabitha DarisiNo ratings yet

- Ndebele Cala SampleDocument26 pagesNdebele Cala SampleaddyNo ratings yet

- ReviewerDocument12 pagesReviewerarlyn teriompoNo ratings yet

- Play and The CurriculumDocument3 pagesPlay and The CurriculumawholelottoloveNo ratings yet

- Observation 3rd Grade EpDocument3 pagesObservation 3rd Grade Epapi-354760139No ratings yet

- 中学语文阅读策略Document44 pages中学语文阅读策略tanzhixuan100% (1)

- Principal InterviewDocument3 pagesPrincipal Interviewapi-488541223No ratings yet

- Sipps Lesson PlanDocument3 pagesSipps Lesson Planapi-355892563No ratings yet

- DLL FABM Week5Document3 pagesDLL FABM Week5sweetzelNo ratings yet

- Grade 5 DLL Q3Document5 pagesGrade 5 DLL Q3Jaypee SembilloNo ratings yet

- Schedule of Subject Offerings For Senior High School NO GRADESDocument1 pageSchedule of Subject Offerings For Senior High School NO GRADESEmill Rivera AsuncionNo ratings yet

- 5 Principles of LearningDocument4 pages5 Principles of LearningSatish UlliNo ratings yet

- دليل المعلم إنجليزي الفصل الأول1 2Document352 pagesدليل المعلم إنجليزي الفصل الأول1 2rawan sabhaNo ratings yet

- EDUC 5210 Discussion Week 1Document2 pagesEDUC 5210 Discussion Week 1daya kaurNo ratings yet

- TPGP TemplateDocument2 pagesTPGP Templateapi-649067754No ratings yet

- Lesson Plan in Science Grade 8: Schools Division of Aurora Puangi National High SchoolDocument2 pagesLesson Plan in Science Grade 8: Schools Division of Aurora Puangi National High SchoolFernando AbuanNo ratings yet

- ST PDPR 12 FinalizedDocument4 pagesST PDPR 12 FinalizedJan Marcus MagpantayNo ratings yet

- Lesson 3Document3 pagesLesson 3Analo Miranda AntigaNo ratings yet

- TIP Module 1 OutputsDocument12 pagesTIP Module 1 OutputsMARYRUTH SEDEÑONo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan Lesson 2 Unit 2 Cambridge English Book 3Document3 pagesLesson Plan Lesson 2 Unit 2 Cambridge English Book 3Fatma EssamNo ratings yet

- Review - Developing Creativity in The Classroom Learning and Innovation For 21st-Century SchoolsDocument4 pagesReview - Developing Creativity in The Classroom Learning and Innovation For 21st-Century SchoolsJmanuelRuceNo ratings yet

- Uts (Black)Document28 pagesUts (Black)Dexter B. BaldisimoNo ratings yet

- ALS Assessment Form Tracks Learner ProgressDocument1 pageALS Assessment Form Tracks Learner ProgressRitchie ModestoNo ratings yet

- 7es Lesson Plan ISODocument4 pages7es Lesson Plan ISOMidrel Jasangas71% (7)

- Davao Central College Teaching Internship ReportDocument92 pagesDavao Central College Teaching Internship ReportIts BorabogNo ratings yet

- Grade 6 Parent Home Learning PlanDocument1 pageGrade 6 Parent Home Learning PlanCatherine RenanteNo ratings yet

- Education Is The Most Powerful Weapon Which You Can Use To Change The WorldDocument2 pagesEducation Is The Most Powerful Weapon Which You Can Use To Change The WorldshazelNo ratings yet