Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Japanese Responses Hai Ee and Un Yes No

Uploaded by

T. OdinnsonCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Japanese Responses Hai Ee and Un Yes No

Uploaded by

T. OdinnsonCopyright:

Available Formats

Language & Communication 20 (2000) 5586

www.elsevier.com/locate/langcom

Japanese responses hai, ee, and un: yes, no, and

beyond

Jerey Angles, Ayumi Nagatomi, Mineharu Nakayama*

Department of East Asian Languages and Literatures, The Ohio State University, 204 Cunz Hall,

1841 Millikin Road, Columbus, OH 43210, USA

Keywords: Japanese; Positive response; Back-channel; Hai; Ee; Un

1. Introduction

The Japanese language has three basic positive response forms: hai, ee, and un,

each of which is used in a variety of contexts. Frequently, the distinction between

them is described as one of politeness or formality (e.g. Tsukuba Language Group,

1991; Association for Japanese Language Teaching, 1994; Guruupu Jamashii, 1998).

As demonstrated below in (1a) and (1b), hai and ee are used with humble and polite

verbal forms while un is used with casual-style speech. Inversely, hai and ee are not

used with casual-style verbals as in (1c).1 Although both hai and ee can be used with

humble verbal forms as in (1a), ee is inappropriate if used in formal situations, such

as when the respondent replies to a person of higher social status or to someone that

is a relative stranger.2

* Corresponding author. Tel.: +1-614-292-5816; fax: +1-614-292-3225.

E-mail address: nakayama.1@osu.edu (M. Nakayama)

1

If sentence (1c) were to end with the sentence nal particle wa, which is common among female

speakers (i.e. `ee, iku-wa' `yes, I will go'), then along with un, ee would also be possible. Hai, however, is

still not possible. The addition of the sentence nal particle wa softens the statement, making it sound

slightly more polite. Ee falls somewhere between the relatively polite/formal hai and the relatively informal/direct un in terms of politeness and formality. With the addition of wa, therefore, it would be

appropriate to shift the initial utterance from un to ee in line with the increased softness and formality of

wa. As for the politeness of the sentence nal particle wa, see Ide (1991), and in regards to interrogatives

without ka such as (1c), see Takahashi and Nakayama (1995).

2

The following abbreviations are used in this paper: Nom=Nominative case marker, Acc=Accusative

case marker, Dat=Dative case marker, Gen=Genitive case marker, Top=Topic marker, SFP=sentence

nal particle, Q=interrogative marker, NM=nominalizer, Cop=copula, Hon=honoric morpheme,

Hum=humble morpheme, Pol=polite morpheme, Pres=non-past tense/non-perfective; Past=past

tense/perfective. For the sake of consistency, we use this gloss system for the cited examples as well.

0271-5309/99/$ - see front matter # 1999 Elsevier Science Ltd. All rights reserved.

PII: S0271-5309(99)00018-X

56

J. Angles et al. / Language & Communication 20 (2000) 5586

1a. A: Irasshaimasu-ka?

go-Hon-Pres-Q

`Will you go?'

B: Hai/ee/*un, mairimasu.

yes

go-Hum-Pres

`Yes, I will go.'

1b. A: Ikimasu

-ka?

go-Pol-Pres -Q

`Will you go?'

B: Hai/ee/*un, ikimasu.

yes

go-Pol-Pres

`Yes, I will go.'

1c. A: Iku?

go-Pres-Q

`Will you go?'

B: *Hai/*ee/un, iku.

yes

go-Pres

`Yes, I will go.'

All three of these response forms are also used as positive answers when responding to a negative question that presupposes that the respondent will agree. For

instance, the examples in (2) show that hai, ee, and un will appear when the

assumption contained in the negative question is correct. Here, the assumption contained in the negative question is that the respondent will not be going somewhere.3

2a. A: Irasshaimasen -ka?

go-Hon-Neg-Pres-Q

`Aren't you going?'

B: Hai/ee/*un, mairimasen.

yes

go-Hum-Neg-Pres

`No, I'm not going.'

2b. A: Ikimasen

-ka?

go-Pol-Neg-Pres-Q

`Aren't you going?'

B: Hai/ee/*un, ikimasen.

yes

go-Pol-Neg-Pres

`No, I'm not going.'

2c. A: Ikanai?

go-Neg-Pres-Q

`Aren't you going?'

3

If (2c) were to contain the sentence nal particle wa, then ee could also be possible. See footnote 1.

J. Angles et al. / Language & Communication 20 (2000) 5586

57

B: *Hai/*ee/un, ikanai.

yes

go-Neg-Pres

`No, I'm not going.'

This use of the Japanese response forms diers from the use of the English word

yes and has been described by various researchers (e.g. Martin, 1962; Kuno, 1973).

Here too, we nd that the associations between response and politeness levels

observed above in (1) again hold true.

Other researchers have discussed dierent functions of hai, ee, and un, such as the

back-channel (or aizuchi in Japanese). Nonetheless, the overwhelming majority of

the studies of Japanese positive response forms deal primarily with hai and ee, and

to the best of our knowledge, there have been few comprehensive studies that contrast all three response forms. This paper will attempt to rectify this problem by

extensively examining the functions of hai, ee, and un. In the process, we will show

that the dierence among the three forms does not merely lie in their formality, but

also their functions. Specically, we will suggest that the fundamental function of

hai is to promote further discourse while that of ee and un is the back-channel. Also,

we will argue that the dierent functions of the three responses are extensions of

those fundamental functions as they operate in dierent contexts.

The next section will present a brief overview of the previous studies of hai and

ee. Following that, we will present a breakdown of the dierent functions of hai,

ee, and un, identifying eleven functions, some of which have been previously

identied by other scholars. Next, we will discuss the fundamental functions of

hai, ee, and un, and afterward, the nal section will present our concluding

remarks.

2. Previous studies

There are many studies that deal with hai and ee. In this section, however, we

will briey discuss these studies by breaking them down into those dealing with hai

and ee as responses and those dealing with them as signals. These two broad

categories will then be further divided. In Section 3 when we examine the functions

of hai, ee, and un individually, we will refer back to the discussions presented

below.

2.1. Responses

One of the most straightforward uses of hai, ee, and un is as a positive response to

a Yes/No question (hereafter YNQ). It was this use which appeared above in (1).

Alfonso (1966, p. 13) states that hai and ee are used to mean yes, but hai has a

connotation of deference and is very polite. Because of this, ee is more common in

normal situations. Other texts explain that ee is less formal than hai (Association for

Japanese Language Teaching, 1994, p. 8), and ee is more polite than un (Tsukuba

Language Group, 1991, p. 52). Similar statements can be found in linguistic studies

58

J. Angles et al. / Language & Communication 20 (2000) 5586

such as Komiya (1986), Yazaki (1990), and Guruupu Jamashii (1998) as well as in

Japanese language textbooks such as Mizutani and Mizutani (1977) and Young and

Nakajima-Okano (1984).

Martin (1962) and Kuno (1973) discuss cases in which hai can be used in

response to a negative question in a fashion that does not parallel the use of the

positive English response yes. The following examples come from Martin (1962, p.

365).

3. A: Kumamoto-e ikimasen -deshita-ka?

Kumamoto-to go-Pol-Neg -Past -Q

`Didn't you go to Kumamoto?'

B: (i) Hai/ee, ikimasen -deshita.

yes

go-Pol-Neg -Past

`No, I didn't.'

(ii) Iie, ikimashita -yo.

no go-Pol-Past -SFP

`Yes, I did indeed.'

As Speaker B's response (i) shows, hai or ee will be used in response to a negative

question if the content of the statement is correct, in other words if Speaker B did

not go to Kumamoto. Conversely, the response would contain iie if B did go. As the

translations above show, the use of hai and ee in response to a negative question is

opposite that of the positive English response yes.

Martin indicates, however, that this pattern of response is not just a matter of

whether or not the question is phrased in the negative form. To demonstrate this, he

raises several examples that contain negative questions but that are actually oblique

requests. Consider examples (4a) and (4b) from Martin (1962, p. 365).

4a. A: Moo sukoshi meshiagarimasen

-ka?

more a little Hon- drink-Neg-Pres -Q

`Won't you have a little more?'

kekkoo-de gozaimasu.

B: Iie, moo

no already enough Cop-Pol-Pres

`No (thanks), I've had ample.'

4b. A: Moo sukoshi meshiagarimasen

-ka?

more a little Hon- drink-Neg-Pres-Q

`Won't you have a little more?'

B: Hai, arigatoo-gozaimasu.

yes thank-you

`Yes, thank you.'

Even though Speaker A's statement takes the form of a negative question,

Speaker A is suggesting that B have more to drink. If A's utterance was interpreted

as a pure question, the response hai would indicate that B is not going to drink

J. Angles et al. / Language & Communication 20 (2000) 5586

59

anything else whereas iie would indicate that B would like some more. However,

since A's utterance is actually an invitation, hai is understood as a positive answer

despite the fact that the verbal is in the negative form, and the response hai, as in

(4b), indicates that B will have some more to drink.

Kuno (1973) further explored this problem of the use of hai in response to

negative questions by examining the questions themselves. In the process of his

investigation, he denes three categories of negative questions, each with its own

rules regarding the use of hai and iie. According to his analysis, in response to

`neutral' negative questions that do not possess a presupposition as to whether the

answer will be positive or negative, hai will introduce an answer that contains a

negative statement. (3) above is an example of such a question.

The second category consists of negative questions that presuppose that the

respondent will reply with a negative answer. In such cases, hai is used to introduce

an answer that contains a negative statement. The following example comes from

Kuno (1973, p. 278):

5. A: Ikanakatta -no desu

-ka?

go-Neg-Past -NM Cop-Pol-Pres -Q

`Is it the case that you didn't go?'

desu.

B: Hai, ikanakatta -n

yes go-Neg-Past-NM Cop-Pol-Pres

`Yes, it is the case that I didn't go.'

However, just like the English yes, hai is used for introducing a positive answer in

response to a negative question that presupposes a positive answer, Kuno's third

category of negative question. Consider the following example from Kuno (1973, p.

278):

6. A: Itta

-no -dewa arimasen

-ka?

go-Past-NM -Cop- exist-Pol-Neg-Pres-Q

`Isn't it the case that you went?'

B: Hai, ikimashita -yo.

yes go-Pol-Past-SFP

`Yes, I did go.'

Although A's question takes the negative form, the focus of the question is the

verb itta (`went'), which takes the positive form. Since Speaker B agrees with this

positive statement, hai is used. In this category, the appropriateness of the

response hai is determined by the syntactic form of the presupposition within the

question.

A number of other works mention that hai and ee can be used as other types of

responses, such as a back-channel noise meaning `I have heard you' (Mizutani,

1988), as a response when one answers the telephone (Kumatoridani, 1992), as a

response to a knock at the door (Jorden and Noda, 1987, p. 26; Mangajin, 1993,

60

J. Angles et al. / Language & Communication 20 (2000) 5586

p. 151), or as a response to the calling of one's name (Jorden and Noda, 1987, p.

26).4 These functions will be further examined in Section 3.5

2.2. Signals

Kitagawa (1980) points out that there are cases in which hai introduces an utterance even when the speaker has not been asked a question or when there is no overt

statement that the speaker might be responding to. For instance, the following

example appears in Kitagawa (1980, p. 114).

7. Teacher: Hai, sore dewa kyoo -wa san-peeji -kara hajimemasu.

then

today-Top page-three-from start-Pol-Pres

`OK, we start from page three today.'

In this case, hai is clearly not a response because it does not follow any other

utterance. Hai is merely used to break the silence and introduce the teacher's statement. Kitagawa explains that in such cases, hai functions as a `bracket marker', a

voicing that helps with the cadence and pulsing of an activity (p. 114). Here, it marks

the beginning of the teacher's statement that the class will begin with page three in

their textbooks. In such cases then, hai serves as a signal that some other statement

is going to follow (Kitagawa notes, however, this hai may, by extension, express the

teacher's acknowledgement that the class is about to start, and thus also serve as a

sort of response to a similar expectation on the part of the class).

Hyuuga (1980) notes that when hai serves as a response, it can be substituted with

ee, but when hai operates as a signal, it cannot be. Consider the following example.

8. A: Shukudai-wa owarimashita -ka?

homework-Top nish-Pol-Pres-Q

`Did you nish your homework?'

B: Hai/ee.

4

Kitagawa (1980) has discussed the back-channel as a category separate from three other responsive

uses of hai: roll call, cooperation-response, and response to request/command. We will discuss all of these

functions further in the next section.

5

Though this problem is only tangentially related to the discussion at hand, it is interesting to note

another other dierence between the English response yes and the Japanese responses hai, ee, and un.

When an English-speaking fan is at a sports game, cheering on a favorite team, he may shout ``Yes!'' when

the team scores a point. Likewise, when teachers are handing back graded tests, students may say ``Yes!''

if they did well, especially in cases in which they were worried about their results. In both cases, it seems

likely that the English ``Yes!'' is in response to unstated questions, in these cases, ``Are they going to make

a point?'' and ``Did I do well?'' respectively. In both situations, however, Japanese-speakers would not say

hai, ee, or un. Instead, a common reponse would be ``Yatta!'' meaning ``[They/I] did it!'' It is clear that the

English response form yes has a pragmatic function that the Japanese response forms hai, ee, and un do

not have. Since the focus of this paper is the pragmatic dierences between hai, ee, and un, the comparison of functions between the dierent response forms in the two languages must be set aside for the time

being.

J. Angles et al. / Language & Communication 20 (2000) 5586

61

Here, the hai comes in clear response to a YNQ and is therefore an example of the

`response' hai. As demonstrated above, one can substitute ee for hai since the relative degree of formality permits it. In (7) above, however, one cannot substitute ee

for hai, even though the degree of formality would permit it because, as Hyuuga

puts it, the hai in (7) is a `signal' and not a response.

Kitagawa (1980) carries the notion of the `signal' hai one step further in accordance with Grice's (1975) Universal Communicative Principles by disassociating the

word hai from notions of agreement and assent. Even cases in which hai can be

interpreted as agreement can be explained in terms of Grice's Maxim of Quality

(`Do not make your contribution more informative than required') and the Maxim

of Manner (`Be perspicuous') (pp. 45, 46). Let us consider (8) again. Kitagawa

argues that hai expresses the respondent's acknowledgment and a willingness to

provide the information that the respondent believes that the addresser desires. Hai

vocalizes acknowledgment and compliance in a brief, orderly manner, thus avoiding

ambiguity. Hai's basic property is therefore that of a signal which responds to the

both the questioner's implicit and explicit expectations, namely acknowledgement

and information-providing, respectively.

Kitagawa attempts to conrm this by identifying situations in which hai might be

used when handing something to someone. Consider the following example from

Kitagawa (1980, p. 113).

9. Female oce worker: Hai/*ee, kore.

this

`Here, take this.'

Male oce worker: Nan dai? Kirei-na nekutai ja nai

-ka?

what Cop pretty-Cop necktie-Top Cop-Neg-Pres-Q?

`What is it? A beautiful tie!'

Female oce worker: Otanjoobi deshoo?

birthday Cop-would

`It's your birthday, isn't it?'

Hai is used in this example when the female worker presents a gift. Here, there is

no preceding overt expression to which hai is responding. Hai can therefore be used

when presenting something, but if a pickpocket, while running away from a policeman, shoves a stolen item into the hands of a passer-by it would be extremely odd

for him to use the word hai. The reason that he cannot use hai is because the passerby does not expect to receive something from the pickpocket. According to Kitagawa, hai is appropriate only when there is a tacit understanding that the speaker

will be presenting something, and therefore, one might consider this `signal' hai as a

response to an unspoken but clearly received message.

Hyuuga (1980) discusses the basic properties of hai in similar terms, but he

questions the validity of creating just one classication for hai. Hyuuga is skeptical

about the explanation that in cases such as (7), hai acts as a vocalized signal of

acknowledgement or as compliance to some unspoken expectation. He dierentiates

the hai that follows an utterance or question (i.e. the hai that comes as a response)

62

J. Angles et al. / Language & Communication 20 (2000) 5586

from the hai that appears without preceding utterances, explaining that the hai

without a preceding utterance has the strong illocutionary force of constructing

discourses and sustaining contexts. Observe the following from Hyuuga (1980, p.

221):

-o hakatte.

10. Nurse says to patient: Hai, taion

temperature -Acc measure-order

`Take your temperature.'

If a speaker intends to introduce a new topic or sustain the current discourse, hai

may be used. This explanation accounts for both the hai that appears without a

preceding utterance and the hai that comes in a response. Later in this paper, we will

return to a similar notion of hai, explaining that hai has the function of what we call

a `promoter.' As we will also show below, ee does not share the `promoter0 property

with hai since ee appears only in responses.

Until this point, we have been looking at previous studies of hai and ee, dividing

them roughly into two categories: responses and signals. The above discussion hints

that these two categorizations are too broad to be exhaustive and that the functions

of hai and ee can be further divided. Okutsu (1988) attempts to further subdivide the

dierent situations in which hai and ee can appear. This study is also of interest in

that it looks at un alongside hai and ee. For these two reasons, we should look at

this study in some detail.

Though Okutsu (1988) does not employ the categories `reply' or `signal' to classify

the various situations in which hai, ee, and un appear, his examples tend to fall

neatly under one rubric or the other. Okutsu notes that hai, ee, and un can all occur

as a reponse to a question that begins with a soo (such as soo desu ka meaning

``Really?''), to an outright YNQ (either negative or positive), to a statement that

ends in the sentence-nal particle ne, or to a statement that ends with some form of

daroo (meaning ``right?'' or ``probably''). In short, Okutsu shows that hai, ee, and

un can be used as responses to various, syntactically dierent types of YNQ or

YNQ-like statements that call for a yes/no-type response of agreement or disagreement. In the following section, we will return to the use of hai, ee, and un in

response to YNQ and YNQ-like statements.

Okutsu also observes that positive responses can also appear in response to

utterances that are not YNQs. For instance, hai, ee, and un can all appear in

response to a demand. Below are the examples which he gives for hai (1988, p. 142),

un (p. 149), and ee (p. 152). Since Okutsu analyzed data which came from a number

of conversations between housewives, each of the three response forms comes in a

quite dierent conversation.

11a. A. Moo sukoshi yoku nette kudasai.

more little

well knead please-Pol

`Please knead it a little better.'

B. Hai.

`All right.'

J. Angles et al. / Language & Communication 20 (2000) 5586

63

11b. A. Jaa kocchi-ni sureba?

well here

make-if

`Why don't you make it here?'

B. Un, jaa soo suru.

well that do -Pres

`Okay, I'll do that.'

11c. A. Soi-ja kore dake suimasen, ja okaeshi-sasete.

well this just sorry,

well return -make

`Well, sorry for this, but let me return it [for you].'

B. Ee.

`Sure.'

In all three examples, A's demand is not a YNQ that demands a positive or

negative response as an answer. Since Okutsu gives quite dierent examples for each

of the three response forms, it is impossible to know from his discussion if hai, ee,

and un can appear as a response to all demands. In the following section, we will

raise the issue of the relative strength of the demand and show how this strength

determines which response form is appropriate. Before faulting Okutsu for not

explaining whether or not these three positive response forms would work with any

demand, we should recognize that the purpose of Okutsu's paper is not to provide

an exhaustive listing of all possible functions of hai, ee, and un. Rather, Okutsu

attempts in this study to measure how frequently hai, ee, and un appear in normal

conversation and to compare these frequencies to those of iie and other negative

responses. In the process of examining the numbers of appearances of positive and

negative responses, he creates general categories reecting where they appear in the

speaker's utterances, and one of these is `hai/ee/un before a demand.'

Okutsu (1988) explains that hai, ee, and un may all be used to reply to a comment.

The following examples illustrate this point (pp. 143, 149, 152, respectively):

12a. A. Nekoze-ni

naranakute ii

-wa -yo.

slumped-Cop become-Neg good-Pres-SFP-SFP

`You shouldn't slump over.'

B. Hai.

`All right.'

12b. A. Sore -wa shoo-ga nai

-wa -yo.

that -Top way-Nom Cop-Neg-Pres-SFP-SFP

`That can't be helped.'

B. Un.

`Yeah.'

12c. A. Kore suzushisoo -de suteki-da

-wa -nee.

this cool-looking-Cop great -Cop-Pres-SFP-SFP

`This one is nice. It looks so cool.'

64

J. Angles et al. / Language & Communication 20 (2000) 5586

B. Ee,

kore-mo ano kirei-desu.

this-too umm pretty-Cop-Pol-Pres

`Yeah, this too. Um, it's pretty.'

As Okutsu notes, all of these sentences are in the form of statements, but these

statements have signicantly dierent illocutionary forces. A's utterance in (12a) is

an oblique suggestion, whereas in both (12b) and (12c), A makes simple statements.

Also, hai and un appear without anything following whereas ee introduces another

statement. Since the examples are so dissimilar, one is reluctant to conclude that the

hai, ee, and un are functioning in identical capacities in each example. Again, we

nd that in using Okutsu's study for our purpose, the categories of functions that he

proposes are not rigorous enough. In Section 3, we will examine the illucutionary

forces of the sentences that can follow hai, ee, and un in order to isolate the dierences between these three words.

The last situation in which Okutsu states that hai, ee, and un can all be used is in

the case of an interlude (ainote in Japanese) in which a speaker takes advantage of a

break in the conversation to insert a statement of his or her own. For instance, see

the following examples (pp. 144, 149, 153, respectively):

13a. A: A, sonna

koto -de.

uh, that-kind thing -Cop

`That about sums it up.'

B: Hai.

`Alright.'

A: Hontoni mooshiwake gozaimasen.

truly

excuse

have-Neg-Pres-Pol

`I'm truly sorry [for what happened].'

13b. A: Ima-da

-to?

now-Cop-Pres-if

`How about now?'

B: Un.

`Okay.'

A: Ueno-kara yojikanhan -gurai nan

desu

-yo-ne.

Ueno-from 4:30

-about-Cop-NM Cop-Pol-Pres -SFP-SFP

`It's about four and a half hours from Ueno.'

13c. A: Ano, honto-wa -nee.

uh, truth -Top -SFP

`Uh, the truth is that. . .'

B: Ee.

`Yeah.'

A: Ii -n -desu

-kedo

ne-NM-Cop-Pol-Pres-but

`That's okay, but. . .'

J. Angles et al. / Language & Communication 20 (2000) 5586

65

Here too, one does not expect a yes/no response in any of these three situations

simply because none of the three statements made by A would call for one. Nonetheless, it is unclear whether hai, ee, and un are functioning in identical fashions. In

all three utterances by B, the words hai, ee, and un serve as an interlude before

speaker A says something else, but in (13b), ee may also be responding to the

implied YNQ, `Shall we go now?' The hai in (13a) and the un in (13c), however,

seem to indicate having heard and thus represent instances of what we shall later

identify as the back-channel noise.

Lastly, Okutsu notes two situations in which only hai can appear. The rst is at

the beginning of a sentence where there was no preceding utterance, as in (7) or (10).

The second is as a response to someone calling out a name, `hello' or some other

similar call. Though noting these functional dierences, Okutsu does not explain the

reasons for the dierent patterns of usage.

The following section of the paper is an attempt to subdivide the various

``responding'' and ``signalling'' functions of hai, ee, and un introduced in the studies

discussed above and to further problematize the notion that all three of these

reponse forms are equivalent. In doing so, we will present similar examples for hai,

ee, and un within each subdivision in order to isolate the incongruency between

these three words.

3. Examination of the functions of hai, ee, and un

This section will discuss eleven functions of hai, some of which have been identied by Kitagawa (1980), Okutsu (1988), and other scholars. We will test to see in

which cases the response words ee and un can also be used and thus attempt to make

a ne delineation between these words. This delineation will then provide the point

of departure for a hypothesis to explain the pragmatic dierences between the three

words. Because some of the broader functions require some lengthy explanation,

this section will deal with them rst before progressing to the other, more straightforward functions.

The focus of our investigation is limited to simply those uses of hai, ee, and un,

with falling intonation. If one were to state any of these words with a rising intonation and look of surprise or confusion, the meaning would become something like

`what are you talking about?', `I didn't understand,' or `I didn't hear you,' depending on the situation. Intonations are, therefore, critical in determining the meanings

and illocutionary forces of these words. The following discussion of hai, ee, and un

and their various functions touches upon some possible dierent intonations, but

fundamentally, the scope of our investigation is limited to falling intonations, not

rising ones.

3.1. Function A: a positive response to yes/no questions, including negative questions

The use of hai in response to a YNQ is perhaps one of the most common uses of

the word but not necessarily the most forthright. In response to YNQs, hai, ee, and

66

J. Angles et al. / Language & Communication 20 (2000) 5586

un may all appear as responses, but there are certain restraints on their use in terms

of formality. Observe the following example from Kitagawa (1980, p. 116).

14a. A: Ikimashita -ka?

go Pol-Past-Q

`Did you go?'

B: Hai/ee, ikimashita.

yes go Pol-Past

`Yes, I did.'

In this exchange, hai is acceptable. Ee can be used if the situation is not extremely

formal. For instance, if speaker A were a governor asking B, a student, if he went

somewhere, B might avoid using ee. However, if A and B were acquaintances of

about the same social rank, one might very well nd ee as a response to A's question. Unlike hai and ee, however, un would sound odd in this context.

14b. A: Ikimashita-ka?

B: *Un, ikimashita.

The reason that un is not acceptable here is that the relative informality of the

word un does not match the relative formality of the verbal ikimashita. The use of

the ending -mashita by B suggests that his entire utterance should be relatively

polite. However, in a similar, less formal situation like (14c), un would be acceptable.

14c. A: Itta?

go-Past?

`Did you go?'

-yo.

B: *Hai/*ee/un, itta

Yes

go-Past-SFP

`Yeah, I went.'

This exchange might take place between two close friends of similar age or

between people that have no formalities between them. In this utterance, un is

acceptable because its relative informality matches the informality of the casual-style

itta yo which follows. Ee would also be acceptable if the informal utterance were to

contain the sentence nal particle wa, which is often used in women's speech (see

footnote 1).

-wa -yo.

14d. B: *Hai/ee/un, itta

Yes

go-Past-SFP-SFP

`Yeah, I went.'

Here, either ee or un would be acceptable because the relative informality of these

two options matches the moderate informality of itta wa yo. Hai is less acceptable

J. Angles et al. / Language & Communication 20 (2000) 5586

67

because it sounds sti in comparison to the relative informality of the remainder of

the sentence.

There are, however, cases in which one might nd hai as a response to an informal

question. Consider the following.

15. A: Chotto, shitsumon-ga aru-kedo, ii?

little

question-Nom exist-but okay-Q

`I have a small question. Is it okay?'

B: Hai/ee/un, doozo.

yes

please

`Sure, go ahead.'

All three possible answers are acceptable, providing that the relationship between

A and B is informal. Hai might be used to show a hint of formality, as if speaker B

was getting down to business by using it. Both ee and un would show a familiar

stance towards A. Likewise, hai could be an acceptable response in (14d) if the

speaker wanted to show a similar hint of formality as if he or she were suddenly

becoming serious. In either of these two cases, the use of hai would place a hint of

psychological distance between the two parties, even though they have a close relationship. It is this touch of psychological distance that would give the utterance an

air of seriousness.

In short, hai, ee, and un may all be used in response to a YNQ. The factor determining the appropriateness of these three choices is the relative degree of formality

in the situation. These observations mesh with traditional explanations of the difference in formality between these options, such as Alfonso's (1966) comments that

hai is more polite and deferent than ee even though their meanings are similar.

It is also worth noting that hai, ee, and un can all be used in response to implied

questions that do not have the syntactic question-marker ka at the end. For

instance, one may ask for conrmation on a point using the sentence-nal particle

ne. Observe the following exchange from Jorden and Noda (1987, p. 189).

16a. A: Jaa, ato ichi-jikan gurai desu

-ne.

well after one-hour about Cop-Pol-Pres-SFP

`Then it's about one hour to go, isn't it?'

B: Ee.

`Yes.'

Here, Jorden and Noda give ee as B's answer, but both hai and un would also

work.

16b. A: Jaa, ato ichi-jikan gurai desu ne.

B: Hai/ee/un.

Un would be appropriate only if the relationship between A and B allows B to

speak informally and directly with A. In both (16a) and (16b), speaker A's utterance

68

J. Angles et al. / Language & Communication 20 (2000) 5586

elicits a response from Speaker B. The illocutionary force of eliciting information

lies within the sentence nal particle ne, a particle that has as one of its functions the

request for conrmation or agreement [see Onoe (1997) for a summary of the functions of ne]. A correct response to an utterance with this ne would either involve a

`yes', `no', soo desu ne (`That's right'), or similar positive or negative agreement.

Therefore, even though the sentence does not contain the particle ka that overtly

creates a question, hai, ee, and un are all correct responses. In short, the particle ne can

elicit the same kinds of responses that one would expect from a YNQ [see the discussion of Okutsu (1988) above and the examples provided in Guruppu Jamashii (1998)].

As discussed in Section 2.1, the word hai can be used to respond to negative

questions in a fashion that does not parallel the use of yes in English. One nds that

in response to negative questions, the words ee and un behave just like hai. For

instance, consider these examples from Kuno (1973, pp. 275276).

17a. A: Nanimo kaimasen

deshita

-ka?

anything buy Pol-Neg Cop-Pol-Past-Q

`Didn't you buy anything?'

deshita.

B: Hai, nanimo kaimasen

yes anything buy-Pol-Neg Cop-Pol-Past

`No, I didn't buy anything.'

Kuno gives hai as a possible response, but one might also nd ee. If one were to

make B's response less overtly polite, one might nd ee or un but not hai as possible

responses.

17b. A: Nanimo kaimasen deshita-ka?

B: *Hai/ee/un, nanimo kawanakatta.

yes

anything buy-Neg-Past

`No, I didn't buy anything.'

Again, the factor that allows the use of ee and un in this sentence is its relative

lack of formality. As we can see from the verb endings, A speaks with relative

politeness to B, but B does not use overt markers of politeness on the end of his

verb. The levels of politeness indicate that B is someone with whom A needs to

maintain a distance (e.g. an older person or someone of superior social status). If B

responded with a more formal, polite utterance, one would be less likely to nd ee,

and un would become inappropriate.

The same pattern can be found in other types of negative questions. Recall (6)

from Kuno (1973, p. 278) (Here relabeled 6a). In this case, ee would also be appropriate answer. Observe then what happens when the verb endings are shifted to the

direct form in (6b).

6a. A: Itta

-no -dewa arimasen

-ka?

go-Past-NM-Cop- exist-Pol-Neg-Pres-Q

`Isn't it the case that you went?'

J. Angles et al. / Language & Communication 20 (2000) 5586

69

B: Hai/ee, ikimashita -yo.

yes

go-Pol-Past-SFP

`Yes, I did go.'

6b. A: Itta

-n -ja nai?

go-Past -NM-Top exist-Neg-Pres-Q

`Isn't it the case that you went?'

-yo.

B: *Hai/*ee/un itta

yes

go-Past-SFP

`Yes, I did go.'

Un is possible in (6b) and therefore, in the case of a negative question asked with

the presupposition that the respondent will agree, ee and un behave similarly to hai.

Each will, of course, be used in accordance to the appropriate rules of formality.

3.2. Function B: back-channel

Yngve (1970, p. 568) describes a back-channel signal as a signal through ``which

the person who has the turn receives short messages such as `yes' and `uh-huh'

without relinquishing the turn.'' Mizutani (1988, p. 4) describes the back-channel

(aizuchi in Japanese) as ``something which the listener inserts midway in the conversation in order to help the progress of the conversation.'' Hai, ee, and un can all

be used in this fashion in a Japanese conversation. Mizutani states that in using

these words, ``one will listen until the completion of one part of the other's speech

then use them in the role of prompting more, as if saying `I have understood thus

far. Please continue''' (1988, p. 4). Generally these back-channel noises come at

pauses or syntactic breaks in the sentence such as after a gerund (Verb-te), a conjunctive kedo or ga `but', or Verb-kara `because' (Mizutani, 1988, p. 7). The following example from Mizutani (1988, p. 9) illustrates these points.

18. A: Sore-de yappari, ningen-no kangaekata

-ni -wa, sunde-iru

then

after-all human-Gen way-of-thinking-for-Top living

kankyoo

-ga

eikyoo -shite ite. . .

environment -Nom inuence -is

being. . .

`All in all, human thought is inuenced by the environment in which one

lives and. . ..'

B: Hai.

A: ame-ga ooi-toka, jishin

-ga

yoku aru-toka, sooshita

rain-Nom lots-and earthquakes-Nom often have-and that-sort-of

shizen kankyoo. . .

nature environment. . .

`natural environments with lots of rain or environments. . .'

B: Shizenkankyoo

nature environment

`Natural environments (Ah, I see what you mean!)'

70

J. Angles et al. / Language & Communication 20 (2000) 5586

A: Hai. Soo iu mono -no eikyoo -ga

tsuyoi-n

such say things-Gen inuence -Nom strong-Cop-Pres-NM

-ja nai

-ka-na.

-Top Neg-Pres-Q -SFP

`That's right. I wonder if such things don't have a strong inuence.'

This conversation contains two appearances of the word hai, but either of these

could be replaced with ee or un (note that both speakers speak in the direct style,

and therefore there is not any need for politeness, hence the use of un is acceptable).

The rst hai comes from speaker B when s/he wants to indicate having heard what A

has said, and therefore, this hai is a typical example of the back-channel. The fact that

one can replace hai, ee, or un with one another (provided that one adjusts the politeness level) indicates that all three words can be used to indicate that one has heard

what the other speaker has stated. Though the function of eliciting more information

is not necessarily contained in the words hai, ee, or un, the context suggests that since

one has been listening, the other speaker should continue with his or her story.

The second appearance of hai comes from speaker A and is slightly harder to

explain because dual functions appear to be at work there. On one hand, this

instance seems to be an acknowledgement of what B has stated, and therefore might

be considered a back-channel response (Mizutani considered it as such). On the

other hand, this hai also seems to contain an element of agreement, as if A is conrming that what B has stated is correct, namely that natural environments are one

factor in shaping with human thought. When B says ``shizen kankyoo'' to him- or

herself, it appears to be done with a degree of internal questioning as B mulls over

the topic of conversation. Speaker A may be responding the internal question ``Is

there a connection between the two?'' that appears to be passing through B's mind,

and therefore, Function A (positive response) may also be at work here. This

example suggests that the functions presented here in Section 3 are not always cutand-dry. In fact, in a particular instance of hai, ee, or un, there may be more than

one function operating at once.

For further discussions of the back-channel function of hai, ee, and un, see Kitagawa (1980), Komiya (1986), Maynard (1987), Matsuda (1988), Tosaku (1994), and

Guruupu Jamashii (1998), among others.

3.3. Function C: acknowledgement of having heard before answering

Kitagawa (1980) gives several examples of the word hai being used in response to

non-YNQ. For instance, see the following example from Kitagawa (1980, p. 108).

19a. A: Oi, shinbun -wa doko da

-ne?

ah newspaper-Top where Cop-Pres-SFP

`Hey, where is the newspaper?'

desu

-yo.

B: Hai, tana -no ue

shelf-Gen above Cop-Pol-Pres-SFP

`It's on the shelf.'

J. Angles et al. / Language & Communication 20 (2000) 5586

71

One nds that in this situation, speaker B can also use ee in place of hai. One

should note that speaker B's utterance is in polite style and is marked overtly with

the polite copula desu. If the utterance were more direct and less polite, then one

would be less likely to nd hai and ee, but more likely to nd un as an answer.

19b. A: Oi, shinbun-wa doko da-ne?

da

-yo.

B: *Hai/*ee/un, tana-no ue

shelf-Gen above Cop-Pres-SFP

`It's on the shelf.'

When the more direct form of the copula is used as in (19b), ee is not acceptable

but un is. This problem seems to be related to the speaker's gender. If B were male,

then the exchange would sound like the sample conversation in (19b), but if B were

female, then one might nd exchange (19a).

19c. A: Oi, shinbun-wa doko da-ne?

B: *Hai/ee/*un, tana-no ue-yo.

In this exchange, the empty copula is used (i.e. the copula does not appear

overtly), and ee is acceptable, but un sounds too brusque or blunt for traditional

female speech.

In (19a)(19c), A's question is a WH-question, not one that would require a

positive or negative response. From this, it is clear that here, hai, ee, and un are not

used to express agreement. As these examples show, hai may be used to acknowledge that one has heard what the other person has stated. This function may be

related to that of the back-channel (Function B), but as in cases (19a)(19c), however, the hai, ee, or un acknowledges having heard and also introduces new information. When used in such situations, hai, ee, and un must be followed by some

statement, otherwise the response becomes awkward. Isolated instances of hai, ee,

and un tend to sound like positive agreement, and so in cases like this when the

question is not one that syntactically calls for agreement or disagreement, hai, ee, or

un alone would sound awkward. This leads one to believe that such instances of hai,

ee, and un are not examples of Function B, the back-channel. For instance, B's

response in the following exchange would sound strikingly odd.

19d. A: Oi, shinbun wa doko da ne?

B: *Hai/*ee/*un. (Not presenting a paper.)

The following example demonstrates that when used in this function, the speaker

does necessarily not have to be of the same mind set as other person. Consider the following example, which is a modied version of a conversation in Natsume (1976, p. 89).6

6

Natsume (1976) was originally published in 1907 and contains `densha-e notte' instead of `densha-ni

notte'. Because the former sounds like dialect, we have chosen the latter to keep all of our cited examples

in standard Japanese.

72

J. Angles et al. / Language & Communication 20 (2000) 5586

20a. A: Kore-kara sugu densha -ni notte kaeranai

-to

hirumeshi -o

Here-from soon train -to get-on go-home-Neg -when lunch

-Acc

kuisokonau.

eat-lose-Pres

`If I don't go right now and get on the train to go home, then I am going

to lose out on lunch.'

B: Sono hirumeshi-o ogoroo

-ja nai

-ka?

that lunch

-Acc let-me-treat-Top-Cop-Neg-Pres-Q

`Why don't I treat you to lunch then?'

A: Un (hesitant intonation) mata kondo-ni shiyoo.

again next-time let's-make

`Well, how about next time?'

Since the relationship between A and B is close, un is used. However, hai and ee

would also work, provided that A speaks to B with distance and with hesitation in

his voice.

20b. A: Kore-kara sugu densha-ni notte kaeranai

-to

ohiru

Here -from soon train -to get-on go-home-Neg-when lunch

-o tabesokonau-n

desu.

-Acc eat-lose -NM Cop-Pol-Pres

B: Sono hirumeshi-o ogoroo ja nai ka?

A: Hai/ee (hesitant intonation), demo mata kondo-ni shimashoo.

but again next-time let's-make-Pol

If these instances of hai, ee, or un in (20a) or (20b) were spoken in a rapid,

ordinary intonation, they would sound like positive responses, and therefore would

clash with the ``how about next time?'' included after them. Kitagawa notes that

``Japanese hai and ee, as well as English yes, can all be used as back-channel

signals, the accompanying intonation contours often serving as an indicator of the

degrees of enthusiasm involved'' (1980, p. 115). The same may also be said of un. A

pause or hesitant intonation here indicates that one is not comfortable with the idea

of eating lunch today, that one has heard or acknowledged the oer but has some

reservations about accepting. This example suggests that hai, ee, and un can be used

to indicate that one has heard, even though the speaker is not of the same mind with

the addressee. This contradicts Kitagawa's theory regarding the use of ee, which

states that the word is used when one is of the same mind with the addressee. When

ee is stated with a bit of hesitation, then the speaker is not of the same mind. Likewise, it is important to note that as in the above example, the hai, ee, or un must be

followed by some information.

20c. A: Kore-kara sugu densha-e notte kaeranai-to hirumeshi-o kuisokonau.

B: Sono hirumeshi-o ogoroo ja nai ka?

A: *Un/*ee/*hai (hesitant intonation).

J. Angles et al. / Language & Communication 20 (2000) 5586

73

Here, even though Speaker A's voice has a note of hesitation about it, it might

seem that A is accepting the oer, though begrudgingly. Unless B were to follow up

with another question to conrm A's desire to go eat, then B would probably not be

clear as to whether A's reservations are serious enough to prevent A from going to

lunch with B. Not enough information is provided to make A's stance clear. Such

cases suggest that intonation and context are extremely important factors in interpreting how the hai, ee, or un will be understood.

Example (21) is another instance of the same phenomenon, also a modied conversation from the same novel by Natsume (p. 86).7

21a. Wife: Oniisan

-no tokoro-e irasshatte onegai nasattara,

elder-brother-Gen place -to go-Hon request do-Hon-if

doo deshoo?

how Cop-would

`Why don't you go to your older brother's place and ask him?'

-ga -ne.

Husband: Un (hesitant intonation), sore mo ii

that also good-Cop-Pres-but-SFP

`Yeah, I suppose that I work but (I don't want to).'

The husband's utterance begins with hesitant intonation. Note also that the

wife's question is not a YNQ that prompts a simple response of true/false or

agreement/disagreement. Un is used in the husband's response above, but either

hai or ee would work, provided the verbal form has the correct level of politeness.

(21b) shows a similar situation with a more formal response from the husband.

(We should note that such conversations expressing such a great degree of psychological distance between man and wife are rather unlikely to occur in modern

Japan.)

21b. Wife: Oniisan-no tokoro-e irasshatte onegai nasattara, doo deshoo?

deshoo

-kedo-ne.

Husband: Hai/ee (hesitant intonation), sore mo ii

that also good Cop-would-but -SFP

`Yeah, I suppose that I work but (I don't want to).'

The un/ee/hai opening the response resembles a back-channel noise (Function B),

yet it introduces further information. It is clear from the second part of the husband's statements in (21a) and (21b) that the hai, ee, and un do not indicate positive

agreement.

In the original, the wife's utterance is as follows:

(i) Oaniisan

-no tokoro-e irashite otanomi nasuttara, doo deshoo?

elder-brother-Gen place -to go-Hon request do-if

how Cop-would

`Why don't you go to your older brother's place and ask him?'

74

J. Angles et al. / Language & Communication 20 (2000) 5586

3.4. Function D: self-conrmation

Guruppu Jamashii (1998, p. 491) notes that hai may be used at the end of an

utterance after a speaker expresses his or her opinion, though such instances often

sound old-fashioned or humbling. It appears, that ee and un can also be used in the

same function. Consider the example below.

22a. A: Amerika-no daigaku -wa doo desu

-ka?

America-Gen university -Top how Cop-Pol-Pres -Q

`What are universities in America like?'

B: Yappari ookii desu

-yo, hai/ee/*un.

Of course big Cop-Pol-Pres -SFP

`They're really big!'

22b. A: Amerika-no daigaku-wa doo?

B: Yappari ookii-yo, *hai/*ee/un.

Example (22a) comes from a rather formal occasion when speaker B is responding

using polite language, and (22b) shows a similar casual exchange in which Speaker B

uses informal language. As before, the choice of hai and ee versus un is based on the

formality and politeness of Speaker B. In both conversations, Speaker A raises a

simple WH-question that intrinsically does not require a yes or no; therefore, B does

not place a negative or positive response at the beginning of the utterance. Why then

after answering A's question does B tack on a hai, ee, or un at the end? It appears

that Speaker B is conrming his or her thoughts internally, and the hai, ee, and un

expresses assurance as to the validity of the opinion expressed.

This function of self-conrmation could be interpreted as an extension of Function A above if one believes that B is saying hai, ee, or un in order to agree with the

previous statement. In other words, B seems to be experiencing a self-referential

thought, looking at her or his speech from a slightly dierent standpoint, checking

the veracity with a mental YNQ, ``Is what I just said correct?'', and answering out

loud. The positive response thus assures him- or herself that this opinion is accurate.

Or alternatively, one could consider this function of self-conrmation as an extension of Function B, the back-channel. The speaker has just gone over what s/he just

said in her or his head and says hai, ee, or un meaning something like `that's what I

am thinking about.' In such a case, the hai (ee, or un) is related to the back-channel

in that the instance of hai/ee/un is a verbal indicator of having nished running

through the mental processes leading up to the comment. In this example, if B's

intonation were hesitant, as if to say ``I'm not so sure that I agree with what I just

said,'' then the instance of hai, ee, or un would more likely be related to Function B

(back-channel) and not Function A (positive response). If B uses a straightforward,

positive, assured intonation, both Functions A and B could be operating simultaneously. Although these alternative interpretations are possible, here, we treat such

instances of hai, ee, and un as a separate function for the sake of brevity.

J. Angles et al. / Language & Communication 20 (2000) 5586

75

3.5. Function E: a response to a suggestion

Hai, ee, and un can all appear in response to a suggestion.8 As in the other functions

previously examined, un can only be used if the speaker's utterance is informal enough.

23a. A: Kore, kanji-de kaitara?

this kanji-in write-if

`Why don't you write this in kanji (Chinese characters)?'

B: Un. Soo suru.

so do-Pres

`Okay, I'll do so.'

This statement must take place between friends, otherwise the response un would

be too informal. For hai and ee, a politer verbal form would be required as in (23b).9

23b. B: Hai/ee. Soo shimasu.

so do-Pol-Pres

`Okay, I'll do so.'

In this conversation, the illocutionary force of Speaker A's statement is that of a

suggestion and therefore is not as strong as a command or request which, as will be

discussed below in Function F, only permits hai or un as a response.

Another possible explanation for the use of all three possibilities here is that these

are actually back-channel responses. Still, it appears that there is a certain degree of

agreement contained within the words hai, ee, and un as they appear here. This may

be because when one hears the above utterance, one mentally understands it in the

following fashion:

23c. A: Kore, kanji-de kaitara,

ii

-n -ja nai?

this kanji-in if-you-write good-NM-Top Cop-Neg-Pres-Q

`Wouldn't it be good if you write this in kanji?'

B: Un. Soo suru.

that do-Pres

`Yes, (you're right). I'll do that.'

8

Kitagawa's (1980) example for the cooperation-response may be classied here in this function if one

takes the following husband's utterance to be an implicit suggestion.

(i) Husband: Aa moo tsumetai biiru-no koto bakari shika kangaerare -nai

oh already cold

beer-Gen matter only except think-able -Neg-Pres-n

-da.

-NM

-Cop-Pres

`Oh, gosh, I can think of nothing but cold beer!'

Wife: Hai. (She heads toward the refrigerator to bring a beer.)

9

If B were female, the informal utterance ``ee, soo suru-wa'' would be possible, but ``hai, soo suru'' and

``hai soo suru-wa'' are awkward unless the speaker is trying to sound slightly more formal as if getting

down to business.

76

J. Angles et al. / Language & Communication 20 (2000) 5586

In this case, A's statement is a full-edged YNQ, and as we saw in Function A

above, hai, ee, and un are all acceptable answers to a YNQ, provided that there is an

appropriate corresponding verbal form.

3.6. Function F: a response to a command or a strong request

When a person is giving a forceful order or a strong request, then only hai or un,

not ee, may be used at the beginning of the following response.10

24. A: Sassa-to shiro!

Quickly do-(imperative)

`Do it right away!'

B: Hai/*ee/un.

25. A: Are-o

motte oide.

that-Acc bring come

`Could you bring that here?'

B: Hai/*ee/un.

In both conversations, Speakers A and B must be a superior and a subordinate or

an adult and a child, respectively. Un would only be appropriate if the relationship

is on familiar terms and if Speaker B does not need to show politeness towards A.

On the other hand, if Speaker A were a customer in a restaurant and Speaker B were

a waiter, then un would not be an acceptable answer since it does not meet the

standards of politeness expected from a waiter in such a situation. As in each of the

functions discussed thus far, the formality of the situation is a crucial factor in

determining whether or not un is permissible. See the following example.

26. Teacher: Bentoo-o chuumon shite koi!

lunch-Acc order

do come-(imperative)

`Order a lunch and bring it here!'

Student: Hai/*ee/*un.

The social need for the student to be polite with his teacher means that he or she is

unable to use un as a response. However, if exchange (26) took place between a husband and wife that do not usually speak formally to one another, then un would work.

The following exchange, which might appear at the end of a telephone conversation, is an example in which the speaker uses a request form but ee is an acceptable

response.

10

The examples that Kitagawa (1980) classies as response to request/command fall into this category.

Okutsu (1988) lumps the use of hai, ee, and un as responses to suggestions and to commands under a

single rubric, suggesting that hai, ee, and un function identically in all situations, regardless of the strength

of the illocutionary force of the preceeding statement. We would argue, however, that some of his examples would fall into what we call Function E and some into Function F.

J. Angles et al. / Language & Communication 20 (2000) 5586

77

27 A: Mata denwa

shite kudasai.

again telephone do please

`Please call again.'

B: Hai/ee/un.

`Sure.'

Speaker A's sentence appears to be a polite command or request because the

polite word kudasai appears at the end, but nevertheless, we nd that ee is an

acceptable response contrary to what was stated above in the discussion of examples (24) and (25). Why? Multiple answers are possible. Because Speaker A's statement is so common as to have lost the illocutionary force of a direct, literal

command, it may not be perceived as such. Perhaps because such phrases ritually

appear at the end of a telephone conversation, B treats A's sentence as a mere

suggestion and hence it is Function E that is actually at work here. Also, B's

utterance also seems to incorporate elements of the back-channel (Function B) in

that B is indicating that s/he has heard what A has to say, and in cases of the backchannel hai, ee, and un are all acceptable. Again, this conversation illustrates that it

is sometimes dicult to isolate exactly which function is at work within a given

utterance.

3.7. Function G: attention-getting

When someone is attempting to get the attention of others, one can use the word

hai to capture the attention of the listener or listeners. The following example is

from Kitagawa (1980, p. 114).

28a. Teacher: Hai/*ee, sore-dewa kyoo -wa san-peeji -kara hajimemasu.

well-then today-Top page-three-from start-Pol-Pres

`OK, we'll start from page three today.'

It seems here that the word hai is promoting further discourse by helping to

establish an open channel of communication between the teachers and students. Ee

cannot be used here, nor could the word un.

28b. Teacher: *Un, sore-dewa kyoo-wa san-peeji-kara hajimemasu.

The factor determining that un is inappropriate in this setting is not the degree

of politeness. This is clear because we nd that even if the sentence were uttered

in a direct style complete with informal verbal endings, the use of the word un

would still be inappropriate. Apparently, it is not restrictions associated with

politeness that bar the use of ee and un here. As Guruupu Jamashii (1998) notes,

in such situations when hai is used to attract attention, ee and un cannot be

substituted for it. Simply put, neither ee nor un possess the attention-getting

function.

78

J. Angles et al. / Language & Communication 20 (2000) 5586

3.8. Function H: a response to attention-getting

Conversely, when someone is being called, then the word hai often appears to

show that an atmosphere of mutually shared attention has been created. Again, this

signal promotes further communication in that it shows that further statements

made by the original speaker will fall upon open ears. The words un and ee do not

appear to have this function and cannot be used here.

29. A: Tanaka-san?

Tanaka-Mr.

`Mr. Tanaka?'

Tanaka: Hai/*ee/*un.

The utterance hai by Mr. Tanaka can have either a rising or a falling intonation.

The following is another example that shows that an attempt to get someone's

attention can be a little more complex.

30. Secretary: Tanaka-san, odenwa desu.

Tanaka-Mr. telephone Cop-Pol-Pres

`Mr. Tanaka, you have a telephone call.'

Tanaka: Hai/*ee/*un.

The secretary's statement here contains at least two illocutionary functions: (a)

getting Mr. Tanaka's attention, and (b) stating that there is a telephone call for him.

The fact that ee and un are not acceptable in this response, however, indicates that

Tanaka-san is responding only to the rst illocutionary force and not the second. As

discussed above, Function B, the back-channel, allows the use of all three possibilities, and therefore, Tanaka's response cannot be a back-channel responding to the

second illocutionary force of the secretary's statement.

Okutsu (1989, p. 11) provides a similar example of hai as a response to attentiongetting.

31. A: Moshimoshi.

(greeting used on telephone)

`Hello?'

B: Hai.

Ee and un could not appear here.

32. A: Moshimoshi.

B: Moshimoshi.

A: *Ee/*un.

Conversation (32) might take place when A is calling B on the telephone. The use

of hai shows that the person has heard and that there is a connection in place for

further communication to occur.

J. Angles et al. / Language & Communication 20 (2000) 5586

79

As mentioned above, Jorden and Noda (1987, p. 26) and Mangajin (1993, p. 151),

also touch upon hai's function as a response to attention-getting when they remark

that hai is the regular response to a knock at one's door or to the calling of one's

name. Again, in such cases, the use of hai indicates that a channel for further communication has been opened and thus promotes successful discourse between the

two parties.

3.9. Function I: presentation/submission

The word hai is frequently used when presenting something to someone. Such

instances of hai cannot be replaced with ee or un. Recall example (9), which originally comes from Kitagawa (1980, p. 113) [here it is renumbered (9a)].

9a. Female oce worker: Hai/*ee, kore.

this

`Here, take this.'

Male oce worker: Nan dai? Kirei-na nekutai ja nai

-ka?

what Cop pretty-Cop necktie-Top Cop-Neg-Pres-Q?

`What is it? A beautiful tie! What for?'

Female oce worker: Otanjoobi deshoo?

birthday Cop-would

`It's your birthday, isn't it?'

Here, hai again is promoting the conversation in the sense that hai allows one to

ease into the situation, prompting the presentation that follows.

In a situation in which one is presenting something to someone else, the words ee

and un cannot be used to capture the person's attention and introduce further discourse.

9b. Female oce worker: *Ee/*un, kore.

Male oce worker: Nan dai? Kirei na nekutai ja nai ka?

3.10. Function J: roll call

When a teacher is calling out the names of students in class, students will answer

with the word hai if present.

33. Teacher: Tanaka-san?

Tanaka: Hai/*ee/*un.

Again, the words ee and un do not appear in this situation. Kitagawa (1980, p.

111) mentions this use, and notes that in such cases, the word hai may be interpreted

as presenting new information to the teacher inquiring about the student. Kitagawa

suggests that this use of hai might be a case of answer-deletion if one considers the

80

J. Angles et al. / Language & Communication 20 (2000) 5586

hai is short-hand for the response ``Yes, I am here.'' Still, it is clear that this hai is

not related to what we have dened in this paper as Function A (positive response)

or Function B (back-channel) because one cannot use ee in this case, and if this

instance were either Function A or B, one would expect to be able to substitute ee

for hai (Un would be unacceptable, however, simply because Japanese society

demands that a student be polite to his teachers, and un sounds excessively familiar).

3.11. Function K: use as a repeated back-channel to cut o partner's speech

When Speaker A is telling Speaker B something that s/he already knows or does

not want to hear, then one might nd the following exchange.

34. A: Asoko-de iroiro -na mondai -ga

atta

kedo. . .

there -in various-Cop problems -Nom exist-Past but

`They had lots of problems there, but. . ..'

B: Hai, hai, hai/*ee, ee, ee/*un, un, un, shitte (i)ru -yo.

known have-SFP

`Yeah, yeah. I know.'

If one repeats the word hai two or more times, then the meaning becomes something like `yeah, yeah, got it already' when the speaker is a more neutral mood or

`enough is enough' when s/he is more irritated. Guruppu Jamashii (1998, p. 490)

notes that when one repeats hai multiple times in response to a question or demand,

then it sends the strong, rude message `I've heard you already!' By repeating what

appears to be the Function B (back-channel), `I have heard you' use of hai multiple

times, one strongly emphasizes the fact that one has heard, and by a leap of logic,

indicates that one does not need to hear anymore. Two or three times is perhaps the

most common number of repetitions when giving the word hai this meaning, though

it can occur with dierent numbers of repetitions.11 It is not possible to say hai only

once and achieve the dismissive aect of Function K.

11

Hai can be repeated fewer than or more than three times within the context of Function K, but three

is the most common number of times. Mangajin (1993) gives an example of the word hai used four times

in order to express the idea `I heard you and I don't want to hear any more' (p. 151). In the example, in a

grandson cuts o his longwinded grandmother who is scolding him for the haphazard fashion in which he

has gone about his wedding preparations.

(i) Grandmother: Shiki

-mo agen,

shinkon-ryokoo -ni-mo ikan. . .

ceremony -even hold-Neg honeymoon

-to-even go-Neg

semete kon'in todoke

gurai taian

-no hi -ni

At-least marriage registration at-least auspicious -Gen day -on

dasan

-to kono isshoo -ni ichido -no tokubetsu -na. . .

turn-in-Neg -with this lifetime -in once -Gen special

-Cop

`You don't even hold a ceremony, you don't take a honeymoon. . .

(so) if you don't at least submit your marriage registration on an

auspicious day then this once-in-a-lifetime special. . .'

Grandson: Hai, hai, hai, hai.

(Footnote 11 continued at foot of next page.)

J. Angles et al. / Language & Communication 20 (2000) 5586

81

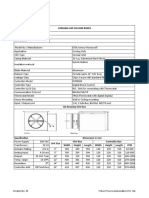

Table 1

Functions of hai, ee, un

Function

Hai

Ee

Un

A: Positive response to YNQ

B: Back-channel

C: Acknowledgement of having heard before answering

D: Self-conrmation

E: Response to a suggestion

F: Response to a command or a strong request

G: Attension-getting

H: Response to attention-getting

I: Presentation/submission

J: Roll call

K: Use as a repeated back-channel to cut o

O

O

O

O

O

O

O

O

O

O

O

O

O

O

O

O

X

X

X

X

X

X

O

O

O

O

O

O

X

X

X

X

X

One can repeat the words un or ee, but one does not produce a statement meaning

`enough is enough.' It only sounds like the back-channel ee and un has been repeated, and there is no signal for the other party to quit speaking. When repeating ee

and un, twice is perhaps the most common number of times (see also Komiya, 1986).

In several of the functions discussed above, the word `promoting' was used to

describe hai's function of introducing another statement or smoothing the transition

into a conversation, but here, it would seem that hai has almost exactly the opposite

function. Here, the repeated use of the word hai actually serves to cut o conversation rather than to further it. We will examine this important point below.

4. Discussion

Table 1 presents a summary of the functions listed above and indicates whether or

not hai, ee, and un, can be used with each. ``O'' indicates that the word can be used

in that function, and ``X'' indicates that it cannot. In the constructing this chart,

levels of formality and politeness have been disregarded.

As Table 1 shows, neither ee nor un seem to have any functions that the word hai

does not also have, and therefore hai is the most inclusive word, covering all of the

functions listed above. One might therefore reach the conclusion that hai is the least

marked and neutral in meaning of the three words hai, ee, and un. It can be used in

situations as varied as roll call to giving a positive response to a YNQ.

The original source of this example is a comic book which bunches all of the above conversation into

two separate balloons, one for the grandmother and one for the student. It is, therefore, unclear where the

grandson's utterances come in relationship to the grandmother's statements. It may be that his hai are

scattered throughout her tirade as back-channel responses (Function B) or they may be all bunched

together at the end (Function K). The most likely possibility is that one or two of them come within her

speech and that the remainder come at the end. Here, as in other cases, intonation and timing are crucial

factors in determining which function is at work, and these elements are not discussed by the accompanying text.

82

J. Angles et al. / Language & Communication 20 (2000) 5586

The fact that one can use hai in so many seemingly disparate cases would seem to

support the hypothesis that hai is generally used to promote further discourse. If we

accept that hai promotes the discourse in a positive way, it makes sense that the

appearance of hai is not solely a function of whether a YNQ is syntactically negative

or positive, but rather that hai appears in response to the questioner's presuppositions. In Function D (self-conrmation), hai reassures the speaker in that what s/he

just said correctly responds to the other's question and thus leaves an open channel

for the listener to react. Functions B (back-channel), C (acknowledgement of having

heard before answering), and H (response to attention-getting) all show the speaker

is paying attention and is actively working to maintain the conversation. Functions

E (response to a suggestion) and F (response to a command or strong request) are

similar to Function A (positive response to a YNQ) in that hai acknowledges having

heard and responds to suggestions, requests, and commands in a positive manner.

Our understanding of `promoting further discourse' also includes engaging or initiating new discourse. This denition explains Functions G (attention-getting), I

(presentation/submission), and J (roll call). The interpretation of hai as a discourse

promoter can thus explain functions A through J.12

12

Hai can also function as a discourse promoter at the end of a phone conversation. Consider the

following example.

(i) A1: Mata denwa

shite kudasai -yo.

again telephone do please -SFP

`Please call me again.'

B1: Hai, wakarimashita.

Mata nomi-ni ikimashoo.

understand-Pol-Past again drink-for go-let's

`Sure. Let's go for a drink again.'

A2: Hai.

B2: Hai. Sayoonara.

A3: Hai.

Hai in B1 and A2 diers from hai in B2 and A3 in that they appear as clear-cut responses to a previous

statement. Ee could be substituted for both the instances of hai in B1 and A2 whereas it could not be for

hai in B2 and A3. This indicates that these two sets of the utterance hai are behaving in dierent functions. Unlike hai in B1 and A2, the instances of hai in B2 and A3 are not vocalized signals of acknowledgement and compliance. Instead, they appear to be indicating a move to a new stage in the conversation

as the participants terminate the present dialogue. Kumatoridani (1992) explains that instances of hai at

the end of a telephone conversation not only accept the content of the conversation that preceded but also

promote the progress of the conversation, helping to carry it through to its conclusion. Szatrowski (1993)

also claims that instances of hai at the end of a telephone conversation indicate a readiness to terminate

the conversation. Mizutani (1988) acknowledges that hai in similar cases helps the conversation proceed

and therefore interprets such instances as back-channels.

Mangajin (1993, p. 153) gives an example of a tailor who has been taking a customer's measurements

and then says the following to let the customer know that he is nished:

(ii) Hai, ii

desho.

good Cop-tentative

`Okay, that should do it.'

The explanation states that the hai is a `signal to end,' but strictly speaking, the hai here actually seems

to be paving the way for the tailor to state that they are nished, not closing o the conversation itself.

Most likely, the tailor is saying hai to get the customer's attention after the several moments of silence in

which he was measuring the customer's suit size, and thus, hai would be operating in what we have called

Function G (attention-getting). It appears that the hai is again serving as a promoter, smoothing the way

for the tailor as he grabs the customer0 s attention and then moves the conversation towards its conclusion.

J. Angles et al. / Language & Communication 20 (2000) 5586

83

The major exception to the idea of hai as a promoter is Function K, the repeated

use of the hai to cut o the conversation. In this case, the word hai seems to be

highly marked in that all one needs to do is to repeat it to send a quite specic signal, namely `I don't want or need to hear anymore.' It appears that in saying ``hai,

hai, hai'', one reverses the ordinary back-channel meaning of the word (Function B)

through sarcasm. Why then don't ee and un, which also can be used as back-channel

noises, serve to cut o conversation when repeated?

One should note that hai, the only back-channel noise that has Function K, is the

most polite of the three words investigated here. This means that when it is used in

ordinary conversation, it hints at a degree of distance between the speaker and

addressee. When used with sarcasm, on the other hand, the ordinary politeness of

hai is inverted, switching from an amicable tone to a more formal, distant one. This

technique is one means of brushing o the other person and indicates that one wants

to end the conversation. Indeed, this appears to be happening with the use of hai in

Function K.

One must also note that the words ee and un place less, if any distance between

speaker and addressee. It is for this reason that ee and un are able to be used in

situations in which the speaker does not need to show a great deal of respect or

deference to the other person. Given the lack of a distancing eect, if one were to

attempt to use ee or un sarcastically, the result does not seem at all dismissive, hence

hai is the only back-channel noise able to produce the dismissive eect of Function

K. Over time, this eect may have crystallized in the utterance ``hai, hai, hai,'' which

serves almost as an idiomatic phrase. The strong tendency for people to repeat hai

specically two or three to produce dismissal suggests that the repeated hai has to

some degree become a set phrase.

In comparison to the word hai, the word un seems to be more strongly marked in

the sense it can be used in fewer situations and therefore carries a more specic

meaning. Of the six functions in which it can be used, four are related to acknowledgement of having heard, and two are related to the positive response. It may be

that the back-channel function of un is its primary function. It is not dicult to

imagine that if un was used as a back-channel in response to a YNQ, it might suggest a positive response. For instance, take the following example.

35. A: Ano hito -wa uta -ga

umai?

that person -Top songs -Nom good

`Is that person good at singing?'