Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Recent Advances in Asthma Management

Uploaded by

Linto JohnOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Recent Advances in Asthma Management

Uploaded by

Linto JohnCopyright:

Available Formats

DRUG REVIEW n

Recent advances in the treatment

and management of asthma

Despite advances in diagnosis and

management of asthma many patients have

poorly controlled symptoms. This article

reviews recent publications on the diagnosis,

assessment and management of asthma in

adults, including the 2014 update of the British

guideline on the management of asthma.

SPL

Neil C Thomson MD, FRCP

sthma is a chronic inflammatory disease of the airways that

affects 300 million people worldwide and 5.4 million people in the UK of whom 80 per cent are adults.1 Despite advances

in the diagnosis and management of asthma,2 surveys indicate

that many patients have poorly controlled symptoms and experience frequent exacerbations.3,4 Three quarters of hospital

admissions and nine out of 10 deaths from asthma are likely

to be preventable.1,5 The financial impact of asthma is considerable, in large part due to the cost of asthma medications, hospital admissions and time lost from work. NHS costs for asthma

are estimated to be around 1 billion per year.

A systematic approach to the evaluation of patients suspected or known to have asthma is helpful and should include

assessment of the diagnosis, identification of the cause(s) of

persistent symptoms and development of a patient-specific

management plan.

Diagnosis

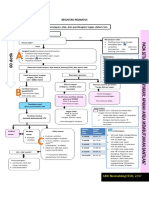

An algorithm based on an assessment of the probability of

asthma and a measure of airflow obstruction is recommended

by the British guideline on the management of asthma in order

to diagnose asthma and to direct further investigations and

treatment (see Figure 1 and Table 1).2 Spirometry is the preferred lung function test to demonstrate the presence and severity of airflow obstruction, because the results are less

dependent on effort and more specific for airway obstruction

than peak expiratory flow (PEF).

NICE is developing guidance on diagnosing and monitoring

asthma that is due to be published in late 2015 or early 2016.6

The report emphasises that asthma is often over diagnosed,

resulting in unnecessary treatment. NICE recommends the measurement of fractional exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO), a biomarker

associated with eosinophilic inflammation and corticosteroid

responsiveness, be used to help support (FeNO level >40 ppb)

or rule out a diagnosis of asthma in people who are considered

prescriber.co.uk

Prescriber 19 September 2015 z 17

Asthma

to have an intermediate probability of asthma and normal spirometry (see Figure 1). Direct bronchial challenge tests with histamine

or methacholine are advocated for cases in which the diagnosis

remains uncertain. The implications of the NICE guidance on diagnosis is not clear, particularly in primary care where there is currently little access to these specialist tests.

Common conditions to be considered in the differential diagnosis in adults include COPD, bronchiectasis, heart failure and

pulmonary thromboembolism, as well as vocal cord dysfunction

and psychogenic breathlessness.

Trigger factors and co-morbidities

Several non-pharmacological management approaches targeting

triggers of asthma and co-morbidities are likely to be effective

in improving asthma control and quality of life, although an evidence base from clinical trials supporting the efficacy of a number of these interventions is generally weak.2 Avoidance of trigger

factors such as allergens, NSAIDs or occupational agents in sensitive individuals, as well as exposure to environmental irritants

such as second-hand smoke, is likely to prevent exacerbations.

Targeting smokers with asthma to quit smoking7 or patients

with a high body mass index (BMI) to lose weight may result in

improvements in asthma symptoms.2,8 Breathing exercise programmes improve quality of life and reduce symptoms when

l DRUG REVIEW n

used as an adjunct to pharmacological treatment.2 Treating coexisting gastro-oesophageal reflux disease does not improve

asthma symptoms.2

Self-management

Self-management education improves asthma control and

reduces emergency use of healthcare resources. The key components of an effective self-management programme are structured education and the provision of personalised asthma

action plans (PAAPs).2 All adults with asthma should be offered

self-management education and PAAPs combined with regular

review by a health professional.

Non-adherence with treatment is one of the most important

factors in poor asthma control.9 Around a quarter of exacerbations are thought to be due to non-adherence with inhaled corticosteroids (ICSs).10 An indication of possible non-adherence

can be assessed by reviewing prescription refill frequency,

including looking for overuse of short-acting bronchodilators.

The ability to detect inadequate adherence based on history

alone is poor though, as the patient may be collecting their ICS

along with their bronchodilator but not using it. Improving adherence can be difficult and effective interventions are often complex. Strategies that may help include adequate explanation of

the indications for treatment, discussion of real and perceived

Symptoms that may be due to asthma

Clinical history and examination

Spirometry (or PEF if spirometry not available)

High probability

Intermediate probability

Obstructive FEV1, FVC

<70%

Normal FEV1, FVC <70%

Low probability

Investigate and treat

alternative diagnosis

Trial of treatment

Response

Response

yes

no

Asthma diagnosis

confirmed

Continue treatment

Assess adherence and

inhaler technique

Reconsider the

diagnosis

Consider further tests

or referral

Reconsider probable

diagnosis

Further investigation

no

yes

Manage according to

alternative diagnosis

Figure 1. Diagnosis of asthma

prescriber.co.uk

Prescriber 19 September 2015 z 19

n DRUG REVIEW l Asthma

concerns of adverse effects of treatment (particularly ICS), simplifying drug treatment regimens, reminders and reinforcement.

Shared decision-making is important as adherence is more

likely when the patient and the health professional agree that

the management approach is appropriate.

Around half of all patients have poor inhaler technique irrespective of the device used.2 Assessing inhaler technique needs

to be part of routine clinical review. The choice of device is based

on the drug to be administered and patient preference, as well

as demonstration by the patient that they are able to use an

inhaler correctly. Patients should be asked to bring their inhalers

with them to each consultation. Prescribing mixed inhaler types

may cause confusion and the British guideline notes that using

the same type of device to deliver preventer and reliever treatments may improve outcomes.2

Monitoring asthma control

Assessing asthma control should incorporate the dual components of symptom control and the future risk of exacerbations

and decline in lung function.

Symptom control can be determined by history taking (symptoms, reliever use) and/or by the use of specific asthma control

questionnaires, eg the Royal College of Physicians (RCP) three

questions (see Table 2), asthma control questionnaire (ACQ)

score or the asthma control test (ACT). The best predictors of

future exacerbations are poor symptom control, a history of an

exacerbation in the previous year, smoking and reduced forced

expiratory volume in one second (FEV1). Excess reliever inhaler

use, defined as greater than one inhaler per month is a risk factor for exacerbations and death from asthma.5

For most patients symptom-based monitoring is adequate.

Serial measurements of PEF are often unreliable, but can be

helpful in selected patients with poor perception of asthma symptoms or with severe disease. NICE guidance on monitoring

asthma does not recommend the use of FeNO to monitor asthma

control, except for patients who are symptomatic despite using

ICS.6 In primary care, monitoring of asthma is best undertaken

by a routine review at least yearly. See Table 3 for Quality and

Outcomes Framework (QOF) indicators in asthma. Each practice

should have a named lead clinician for asthma services.5

Increased probability of asthma

Symptoms worse at night and in the morning

Symptoms associated with triggers such as exercise,

allergen exposure, cold air

Symptoms after taking aspirin or beta-blockers

History of atopic disorder

Family history of asthma/atopic disorder

Widespread wheeze on examination

Unexplained low lung function or blood eosinophilia

Decreased probability of asthma

Prominent dizziness, light-headedness

Chronic productive cough in the absence of wheeze or

breathlessness

Repeatedly normal physical examination of chest when

symptomatic

Voice disturbance

Symptoms with colds only

Cardiac disease

Significant smoking history (ie >20 pack-years)

Normal lung function when symptomatic

Spirometry

Normal spirometry (or PEF) does not exclude the diagnosis of

asthma in a patient who is asymptomatic

Smokers with asthma

The prevalence of smoking in asthma is similar to the

general population; asthma can occur in patients with a

significant smoking history

Table 1. Notes on the diagnosis of asthma2

and a step-up in treatment with the addition of a long-acting

beta2 agonist (LABA) may be required. Doubling the dose of

ICS, from 1000 to 2000g/day, at the onset of an exacerbation does not reduce the risk of exacerbations requiring rescue

oral corticosteroids.11 Once daily ICSs include ciclesonide and

mometasone.

ICS/LABA combinations

Step-wise approach

The step-wise approach to treatment should be integrated into

a management plan that includes non-pharmacological management approaches where appropriate, as well as regular monitoring of symptom control and risk of future exacerbations and

as well as supported self-management and assessment of

adherence and inhaler technique (see Figure 2).2 These assessments should be undertaken prior to a step-up or step-down in

treatment. Several issues concerning the efficacy and safety of

commonly used drugs for asthma within the context of this

approach are discussed briefly below.

ICSs

ICS is the recommended preventer for the treatment of adults

with asthma. ICSs are less effective in smokers with asthma7

20 z Prescriber 19 September 2015

Inhaled LABA is the first choice add-on therapy for adults with

poorly controlled asthma despite taking ICSs at doses of 200

800g beclometasone dipropionate/day. The asthma guideline

recommends that LABAs should be prescribed in fixed-dose

combination with an ICS to aid adherence and reduce the likelihood of LABA monotherapy.2

Currently available combination products are administered

twice daily, namely fluticasone propionate/salmeterol (Seretide),

budesonide/formoterol (Symbicort and DuoResp Spiromax),

extra-fine beclometasone/formoterol (Fostair) and fluticasone

propionate/formoterol (Flutiform). A new combination multidose

dry powder inhaler device (Relvar Ellipta) containing the ICS

fluticasone furoate and the LABA vilanterol trifenatate (92/22

and 184/22g) is licensed as the first once-daily maintenance

treatment for asthma.12,13 Once-daily treatment with fluticasone/

prescriber.co.uk

Asthma

In the last month/week have you had difficulty sleeping

due to your asthma (including cough symptoms)?

Have you had your usual asthma symptoms (eg cough,

wheeze, chest tightness, shortness of breath) during the day?

Has your asthma interfered with your usual daily activities

(eg school, work, housework)?

Note: 1 yes indicates medium morbidity and 2 or 3 yes

answers indicate high morbidity

Table 2. The RCP three questions for determining asthma control

vilanterol has the potential to improve adherence in asthma,

although to date there are no published data to support

improved adherence or effectiveness compared to other

ICS/LABA combinations. Depending on the dose of ICS used,

some alternative ICS/LABA combination inhalers are available

at a lower daily cost.

The Single inhaler Maintenance And Reliever Therapy

(SMART) regimen, using both budesonide and formoterol

(Symbicort SMART), or the combination of inhaled extra-fine

particle size beclometasone and formoterol pressurised

metered dose inhaler as Maintenance And Reliever Therapy

(Fostair MART) regimen for maintenance treatment and relief

of symptoms, reduce the frequency of severe exacerbations

compared to a fixed-dose combination plus a short-acting beta2agonist (SABA) as a reliever.14,15

Overall, studies indicate that the single combination

inhaler approach and the fixed-dose combination strategy are

both effective options for patients at Step 3 who are poorly

controlled. A decision on which strategy to use is likely to be

influenced by patient preference and the ability of the patient

to understand the correct use of the single combination

inhaler regimen.2

l DRUG REVIEW n

Long-acting muscarinic antagonists

Recent clinical trials have demonstrated the efficacy of the longacting muscarinic antagonist bronchodilator tiotropium (Spiriva

Respimat) in adults with asthma who have persistent airflow

obstruction. Once-daily tiotropium added to medium-dose ICS

reduced airflow obstruction and improved symptom control in

patients with moderate symptomatic asthma16 and may be

superior to doubling of the dose of ICS.17 In patients with poorly

controlled asthma who have reduced lung function despite the

use of combination therapy (ICS plus LABA), the addition of

tiotropium increased the time to the first severe exacerbation

and provided modest sustained bronchodilation.18

Tiotropium (Spiriva Respimat 5g daily) was licensed in

2014 as an add-on maintenance bronchodilator treatment for

use in adults who are currently treated with ICS (800g budesonide/day or equivalent) and a LABA (Step 4 British guideline),

and who experienced one or more severe exacerbations in the

previous year. Tiotropium has not been compared with other

add-on therapies at Step 4 eg high dose ICS or leukotriene

antagonist, or in adults with asthma without persistent airflow

obstruction (post-bronchodilator FEV1 <80 per cent of predicted).

Spiriva Respimat should be used with caution in people with

certain cardiac conditions, who were excluded from clinical trials

of tiotropium.

Severe asthma

For the 510 per cent of patients with severe asthma, there are

limited treatment options (Steps 4 and 5, see Figure 2).19,20

These patients often have poorly controlled asthma despite

treatment with high-dose ICS and LABAs plus other add-on therapies and, at Step 5, oral corticosteroids.

Omalizumab, a humanised monoclonal antibody that binds

circulating IgE antibody, is indicated for patients with severe allergic asthma (see Table 4). Its use is associated with improvements

Indicator

Points

Achievement

thresholds

Records

AST001. The contractor establishes and maintains a register of patients with asthma, excluding

patients with asthma who have been prescribed no asthma-related drugs in the preceding 12 months

Initial diagnosis

AST002. The percentage of patients aged 8 or over with asthma (diagnosed on or after 1 April 2006),

on the register, with measures of variability or reversibility recorded between 3 months before or any

time after diagnosis

15

4580%

Ongoing treatment

AST003. The percentage of patients with asthma, on the register, who have had asthma review in the

preceding 12 months that includes an assessment of asthma control using the 3 RCP questions (NICE

2011 menu ID: NM23)

20

4570%

AST004. The percentage of patients with asthma aged 14 or over and who have not attained the age of

20, on the register, in whom there is a record of smoking status in the preceding 12 months

4580%

Table 3. 20152016 QOF indicators for asthma

prescriber.co.uk

Prescriber 19 September 2015 z 21

Asthma

Adults and children

>12 years

Step 1

Mild intermittent

asthma

Step 2

Regular preventer

therapy

Step 3

Initial add-on

therapy

Children 512 years

l DRUG REVIEW n

Children <5 years

Inhaled SABA as required

Add inhaled steroid

200800g per day*

Add inhaled steroid 200400g per day*

Consider other preventer drug such as LTRA if steroid cannot

be used

Add inhaled LABA:

If good response, continue

If benefit but control still inadequate, continue LABA and

increase inhaled steroid to 800g (children <12 400g) per day*

If no response to LABA, stop and increase inhaled steroid to

800g (children <12 400g) per day*

If control still inadequate, trial other therapies such as LTRA,

SR theophylline

In children taking inhaled

steroid 200400g per

day,* consider adding LTRA

In children taking LTRA

alone, reconsider adding

inhaled steroid 200

400g per day*

In children <2 years old consider proceeding to Step 4

Step 4

persistent poor

control

Step 5

continuous or

frequent oral

steroid

Trials of

Increase inhaled steroid

up to 2000g per day*

Adding in further drugs

such as LTRA, SR theophylline, beta2-agonist

tablet

Trial of increasing inhaled

steroid up to 800g per

day*

Daily steroid tablets

Maintain high-dose inhaled steroid (2000g* adults, 800g*

children <12)

Consider other treatments such as immunosuppressives,

omalizumab

Refer to respiratory physician

Refer to respiratory

physician

At each step check:

Current symptoms

Risk of exacerbation

Adherence

Inhaler technique

Triggers

Co-morbidities

Consider nonpharmacological approaches

Action plan

Need for specialist referral (particularly at steps 4

and 5)

SABA: short-acting beta2-agonist; LABA: long-acting beta2-agonist; LTRA: leukotriene receptor antagonist; SR: slow release

*Refers to beclometasone or budesonide; equivalent dosages for fluticasone and mometasone should be halved; ciclesonide is also

more potent although its precise equivalence to beclometasone is unclear

Figure 2. Step-wise approach to the management of asthma in adults, in children aged 512 years and in children less than 5 years

prescriber.co.uk

Prescriber 19 September 2015 z 23

n DRUG REVIEW l Asthma

in quality of life and a reduction in exacerbations,21,22 although

the yearly cost per patient is considerable.

Bronchial thermoplasty, which involves the delivery of

radiofrequency energy to the airways to reduce airway smooth

muscle mass has been shown to improve quality of life and

reduce exacerbation in severe asthma.23,24 The asthma guide Omalizumab is recommended as an option for treating severe persistent confirmed allergic IgE-mediated asthma as an add-on to optimised

standard therapy in people aged 6 years and older:

Who need continuous or frequent treatment with oral corticosteroids

(defined as 4 or more courses in the previous year), and

Only if the manufacturer makes omalizumab available with the discount agreed in the patient access scheme.

Optimised standard therapy is defined as a full trial of and, if tolerated,

documented compliance with inhaled high-dose corticosteroids, longacting beta2 agonists, leukotriene receptor antagonists, theophyllines,

oral corticosteroids, and smoking cessation if clinically appropriate.

People currently receiving omalizumab whose disease does not meet

the criteria in 1.1 should be able to continue treatment until they and

their clinician consider it appropriate to stop

Table 4. NICE guidance on the use of omalizumab in severe persistent allergic

asthma (TA278)

KEY POINTS

n Evaluation should include assessment of the diagnosis, identification

of the cause(s) of persistent symptoms and development of a management plan

n An algorithm based on an assessment of the probability of asthma

and a measure of airflow obstruction is recommended by the British

guideline on the management of asthma in order to diagnose asthma

n Avoidance of trigger factors in sensitive individuals is likely to prevent

exacerbations

n Non-adherence with treatment is one of the most important factors in

poor asthma control

n Assessing inhaler technique needs to be part of routine clinical review

n Self-management education improves asthma control and reduces

emergency use of healthcare resources

n Assessing asthma control should incorporate the dual components of

symptom control and the future risk of exacerbations and decline in

lung function

n The best predictors of future exacerbations are poor symptom control,

a history of an exacerbation in the previous year, smoking and reduced

FEV1

n The step-wise approach to treatment should be integrated into a management plan that includes nonpharmacological approaches where

appropriate and routine clinical review

n LABAs should be prescribed in fixed-dose combination with an ICS to

aid adherence

n Omalizumab is indicated in severe allergic asthma

24 z Prescriber 19 September 2015

lines advise that bronchial thermoplasty may be considered for

the treatment of moderate to severe asthma in patients who

have poorly controlled asthma despite maximal therapy.2 The

procedure is available in several specialist centres in the UK.

Biological agents targeting proinflammatory cytokines such as

interleukin-5 and interleukin-13 are under development for

severe asthma.19,20

Conclusion

The diagnosis of asthma is based on an assessment of the probability of asthma and evidence of variable airflow obstruction.

The step-wise approach to drug treatment should be integrated into a patient-centered management plan that includes:

non-pharmacological management approaches where appropriate; regular monitoring of symptom control and risk of future

exacerbations; supported self-management; and assessment

of adherence and inhaler technique. Better therapies are

required for the 510 per cent of people with severe asthma.

References

1. Asthma UK. 2015 (http://bit.ly/U5IJXI).

2. British Thoracic Society Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines N. British

guideline on the management of asthma. Thorax 2014;69:i1i192.

3. Price D, et al. NPJ Prim Care Respir Med 2014;24:14009.

4. Fletcher M, Hiles D. Prim Care Respir J 2013;22:4318.

5. Why asthma still kills: the National Review of Asthma Deaths (NRAD)

Confidential Enquiry report. 2014 (http://bit.ly/1LFMYSk).

6. NICE Clinical guideline methods, evidence and recommendations,

January 2015 (draft for consultation). 2015 (http://bit.ly/1KpvLec).

7. Thomson N, Chaudhuri R. Curr Opin Pulm Med 2009;15:3945.

8. Ledford DK, Lockey RF. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol 2013;13:7886.

9. Heaney LG, Horne R. Thorax 2012;67:26870.

10. Williams LK, et al. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2011;128:118591.

11. Quon B, et al. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2010;10.

Art. No.: CD007524 .

12. OByrne PM, et al. Eur Respir J 2014;43:77382.

13. Woodcock A, et al. Chest 2013;144:12229.

14. Patel M, et al. Lancet Respir Med 2013;1:3242.

15. Papi A, et al. Lancet Respir Med 2013;1:2331.

16. Kerstjens HAM, et al. Lancet Respir Med 2015;3:36776.

17. Peters SP, et al. N Engl J Med 2010;363:171526.

18. Kerstjens HAM, et al. N Engl J Med 2012;367:1198207.

19. Thomson N, et al. BMC Medicine 2011;9:102.

20. Olin JT, Wechsler ME. BMJ 2014;349:g5517.

21. Normansell R, et al. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews

2014;1:CD003559.

22. Thomson NC. Evidence Based Medicine 2014;19:135.

23. Thomson NC, et al. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol 2012;12:2418.

24. Torrego A, et al. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014;3:CD009910.

Declaration of interests

Professor Thomson has participated in advisory boards and/or

received consultancy/lecture fees and industry-sponsored grant

funding to the University of Glasgow from a number of pharmaceutical companies.

Neil Thomson is emeritus professor of respiratory medicine

Institute of Infection, Immunity and Inflammation, University

of Glasgow

prescriber.co.uk

You might also like

- 2.2 X 2 Feet Macgd3 Cake DesignDocument1 page2.2 X 2 Feet Macgd3 Cake DesignLinto JohnNo ratings yet

- Neutrophil Stunning by Metoprolol Reduces Infarct Size: ArticleDocument15 pagesNeutrophil Stunning by Metoprolol Reduces Infarct Size: ArticleLinto JohnNo ratings yet

- Same Eliminates Free Radicals, Protects LiverDocument1 pageSame Eliminates Free Radicals, Protects LiverLinto JohnNo ratings yet

- 1 S-Adenosyl-L-methionine Synthetase and Phospholipid Methyltransferase Are Inhibited in Human Cirrhosis. Hepatology 1988 8:65-8Document2 pages1 S-Adenosyl-L-methionine Synthetase and Phospholipid Methyltransferase Are Inhibited in Human Cirrhosis. Hepatology 1988 8:65-8Linto JohnNo ratings yet

- Evidences On SAMe in Liver DiseasesDocument1 pageEvidences On SAMe in Liver DiseasesLinto JohnNo ratings yet

- Metoprolol in The Treatment of Cardiovascular Disease: A Critical ReappraisalDocument19 pagesMetoprolol in The Treatment of Cardiovascular Disease: A Critical ReappraisalLinto JohnNo ratings yet

- Evolving Therapies For Myocardial Ischemia-Reperfusion InjuryDocument18 pagesEvolving Therapies For Myocardial Ischemia-Reperfusion InjuryLinto JohnNo ratings yet

- Airway Inflammation Induced SputumDocument2 pagesAirway Inflammation Induced SputumLinto JohnNo ratings yet

- Pathophysiology and Therapy of Myocardial Ischaemia/reperfusion SyndromeDocument14 pagesPathophysiology and Therapy of Myocardial Ischaemia/reperfusion SyndromeLinto JohnNo ratings yet

- Restenosis After Coronary and Peripheral Intervention: Efficacy and Clinical Impact of CilostazolDocument8 pagesRestenosis After Coronary and Peripheral Intervention: Efficacy and Clinical Impact of CilostazolLinto JohnNo ratings yet

- HF GuidelinesDocument76 pagesHF GuidelinesLinto JohnNo ratings yet

- Exacerbations GoldDocument10 pagesExacerbations GoldLinto JohnNo ratings yet

- Clopidogrel Versus Ticagrelor o Prasugrel en Pacientes de 70 Años o Más Con Síndrome Coronario Agudo Sin Elevación Del Segmento ST (POPular AGE)Document8 pagesClopidogrel Versus Ticagrelor o Prasugrel en Pacientes de 70 Años o Más Con Síndrome Coronario Agudo Sin Elevación Del Segmento ST (POPular AGE)Frank Antony Arizabal GaldosNo ratings yet

- GINA Flare UpsDocument15 pagesGINA Flare UpsLinto JohnNo ratings yet

- Final Evolution in Respiratory Medicine - Copy1Document49 pagesFinal Evolution in Respiratory Medicine - Copy1Linto JohnNo ratings yet

- StatusasthmaticusDocument40 pagesStatusasthmaticusLinto JohnNo ratings yet

- Pharma MarketingDocument167 pagesPharma MarketingLinto JohnNo ratings yet

- Air Pollution A Big Killer in India: Source: World Health OrganisationDocument1 pageAir Pollution A Big Killer in India: Source: World Health OrganisationLinto JohnNo ratings yet

- Exacerbations GoldDocument10 pagesExacerbations GoldLinto JohnNo ratings yet

- A New Strategy in Reliever Therapy Budesonide/Formoterol Maintenance PlusDocument13 pagesA New Strategy in Reliever Therapy Budesonide/Formoterol Maintenance PlusLinto JohnNo ratings yet

- Viral Infection in Community-Acquired Pneumonia: A Systematic Review and Meta-AnalysisDocument11 pagesViral Infection in Community-Acquired Pneumonia: A Systematic Review and Meta-AnalysisLinto JohnNo ratings yet

- What Is CopdDocument4 pagesWhat Is CopdLinto JohnNo ratings yet

- Coming SoonDocument1 pageComing SoonLinto JohnNo ratings yet

- Zero Day REspi Test PaperDocument3 pagesZero Day REspi Test PaperLinto JohnNo ratings yet

- For Uncontrolled Asthma Despite ICS: Tiotropium Add-On TXDocument1 pageFor Uncontrolled Asthma Despite ICS: Tiotropium Add-On TXLinto JohnNo ratings yet

- Coming SoonDocument1 pageComing SoonLinto JohnNo ratings yet

- AutohalerDocument51 pagesAutohalerLinto JohnNo ratings yet

- Coming SoonDocument1 pageComing SoonLinto JohnNo ratings yet

- Potential Drug That Could Help Treat Cystic Fibrosis Identified by ResearchersDocument2 pagesPotential Drug That Could Help Treat Cystic Fibrosis Identified by ResearchersLinto JohnNo ratings yet

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (120)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Clinicopathologic Conference: Governor Celestino Gallares Memorial Hospital Department of Obstetrics and GynecologyDocument57 pagesClinicopathologic Conference: Governor Celestino Gallares Memorial Hospital Department of Obstetrics and GynecologyramwshNo ratings yet

- 7.down SyndromeDocument15 pages7.down SyndromeGadarNo ratings yet

- 9650-0301-01 Rev. MDocument48 pages9650-0301-01 Rev. MCarlos AndresNo ratings yet

- Henderson's 14 ComponentsDocument6 pagesHenderson's 14 ComponentsJim RashidNo ratings yet

- Nursing NotesDocument6 pagesNursing NotesTiffany SimnickNo ratings yet

- Clinical Manual - Part 2 - Drug Infusion Guidelines Revised - July 2015 - V7.11Document58 pagesClinical Manual - Part 2 - Drug Infusion Guidelines Revised - July 2015 - V7.11Jayaprakash KuppusamyNo ratings yet

- ICON 2016 Febrile Neutropenia GuidelinesDocument34 pagesICON 2016 Febrile Neutropenia GuidelinesTor Ja100% (1)

- Renal NursinglDocument36 pagesRenal NursinglgireeshsachinNo ratings yet

- iTIJ:: P4Yicai. Etfal - Uati OnDocument4 pagesiTIJ:: P4Yicai. Etfal - Uati OnBartolome MercadoNo ratings yet

- WHO - HQ - Reports G2 PROD EXT TBCountryProfileDocument1 pageWHO - HQ - Reports G2 PROD EXT TBCountryProfileAngelo Santos EstrellaNo ratings yet

- Canine Influenza FactsDocument5 pagesCanine Influenza FactsWIS Digital News StaffNo ratings yet

- Final PPT SiDocument38 pagesFinal PPT SiSaad IqbalNo ratings yet

- Approach To A Failed Bankart's SurgeryDocument56 pagesApproach To A Failed Bankart's Surgerychandan noel100% (1)

- Psychotropic Drug Overdose The Death of The Hollywood Celebrity Heath LedgerDocument5 pagesPsychotropic Drug Overdose The Death of The Hollywood Celebrity Heath LedgerlalipredebonNo ratings yet

- Activity Sheets in Science 5 Quarter 2, Week 1: Parts of The Reproductive System and Their FunctionsDocument6 pagesActivity Sheets in Science 5 Quarter 2, Week 1: Parts of The Reproductive System and Their Functionsricardo salayonNo ratings yet

- 2) Megaloblastic AnemiaDocument17 pages2) Megaloblastic AnemiaAndrea Aprilia100% (1)

- 32 Oet Reading Summary 2.0-697-717Document21 pages32 Oet Reading Summary 2.0-697-717Santhus100% (7)

- Legal Aspects of MedicationDocument17 pagesLegal Aspects of MedicationRitaNo ratings yet

- C-Reactive Protein: TurbilatexDocument1 pageC-Reactive Protein: TurbilatexAssane Senghor100% (1)

- Lecture 9 Physical Therapy Management of Vestibular HypofunctionDocument24 pagesLecture 9 Physical Therapy Management of Vestibular Hypofunctionrana.mohammead1422No ratings yet

- Bird Mark 7A Respirator BrochureDocument2 pagesBird Mark 7A Respirator BrochureLos Infantes Ska Jazz100% (4)

- Therapeutic Management of Clinical Mastitis in Goat: A Case StudyDocument5 pagesTherapeutic Management of Clinical Mastitis in Goat: A Case StudyIJAR JOURNALNo ratings yet

- 2926 Getinge Da Vinci Brochure 190301 en NonusDocument5 pages2926 Getinge Da Vinci Brochure 190301 en NonusHELIONo ratings yet

- The Prevention and Cure Effects of Aspirin Eugenol Ester On Hyperlipidemia and Its MetabonomicsDocument108 pagesThe Prevention and Cure Effects of Aspirin Eugenol Ester On Hyperlipidemia and Its MetabonomicsKavisa GhoshNo ratings yet

- Vasofix SafetyDocument6 pagesVasofix Safetydex99No ratings yet

- Abdullah M. Kharbosh, B.SC., PharmDocument27 pagesAbdullah M. Kharbosh, B.SC., PharmsrirampharmaNo ratings yet

- Jaw Fractures Managing The Whole PatientDocument2 pagesJaw Fractures Managing The Whole PatientElisa BaronNo ratings yet

- 1-29-20 Diabetes Protocol Draft With Pandya and Alvarez EditsDocument12 pages1-29-20 Diabetes Protocol Draft With Pandya and Alvarez Editsapi-552486649No ratings yet

- Resusitasi NeonatusDocument7 pagesResusitasi NeonatusIqbal Miftahul HudaNo ratings yet

- Polio VaccineDocument10 pagesPolio VaccineLiiaa SiiNouunaa JupheeNo ratings yet