Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Trauma As A Neglected Etiological PDF

Uploaded by

SašaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Trauma As A Neglected Etiological PDF

Uploaded by

SašaCopyright:

Available Formats

Aleksandar Dimitrijevic, PhD1

Originalni nauni rad

Assistant Professor, Department of Psychology, UDK: 159.944.4: 616.89-008.1

Faculty of Philosophy, University of Belgrade

Primljeno: 11.5.2015.

Substitute Professor,

DOI: 10.2298/SOC1502286D

International Psychoanalytic University, Berlin

TRAUMA AS A NEGLECTED ETIOLOGICAL

FACTOR OF MENTAL DISORDERS

ABSTRACT Throughout the history of mental health care field, trauma was

prescribed different and frequently opposing roles. In psychoanalysis, the attitude

toward trauma was ambiguous: it was considered a crucial factor, but at the same

time its role could happen to be minimized. In biological psychiatry, it is seen as a

dominant cause of some disorders and completely irrelevant for the others.

In this paper, two issues are discussed: frequency of traumatic events in general

population and among persons with mental disorders; and hypothesized intrapsychic

mechanisms that lead to detrimental consequences of trauma on mental health.

It is advocated that prevention of early, especially attachment, trauma should be

the focus of our work in dealing with mental disorders.

KEYWORDS: trauma, mental disorder, attachment, mentalization

SAETAK Tokom razvoja zatite mentalnog zdravlja, trauma je esto dobijala

razliite, pa ak i suprotstavljene uloge. U psihoanalizi je smatrana kljunim

faktorom nastanka mentalnih poremeaja, ali je u isto vreme mogla biti i

zanemarena, dok je u biolokoj psihijatriji prihvaena za glavni uzrok nekih

poremeaja ali i kao potpuno nevana za druge.

U ovom tekstu u diskutovati dva pitanja: uestalost traumatskih dogaaja u

optoj populaciji i meu osobama s mentalnim poremeajima, te pretpostavljene

intrapsihike mehanizme koji vode do nepoeljnih posledica traume po mentalno

zdravlje.

Na osnovu svih podataka moe se zakljuiti da bi prevencija ranih trauma, a

posebno trauma u odnosima vezanosti, trebalo da bude fokus u naem radu s

osobama koje pate od mentalnih poremeaja.

KLJUNE REI trauma, mentalni poremeaj, vezanost, mentalizacija

adimitri@f.bg.ac.rs, a.dimitrijevic@ipu-berlin.de

Aleksandar Dimitrijevic: Trauma as a neglected etiological factor of mental disorders

287

History of trauma in the mental health care field

A long debate about the role of trauma started with French psychiatrists of

the XIX century and Freud (e.g.: Ellenberger, 1970; Hacking, 1998; Makari, 2008).

While Freud believed that actual trauma is a necessary trigger for neurosis, his

opinion about the infantile trauma changed. Initially, he found infantile trauma

to be of utmost importance, because it would define the fixation point and thus

the symptoms of the disorder (e.g., Bonomi, 2015). In a letter to Wilhelm Fliess,

however, on October 15, 1897, Freud introduced the conception of what will

come to be known the Oedipus complex: it was childrens fantasy that defined

the root of the disorder and not the actual traumatic events (Masson, 1985, p.

272). The shift was so dramatic that it was labeled the assault on truth about

the molestation of children in the conservative Vienna (Masson, 1992).

It had not been until the second half of the 1920s that this view was

challenged. In two of his last papers, Sandor Ferenczi tried to bring trauma

back to the centre of attention. He described developmental and clinical details

related to problems faced by the unwanted children, who are traumatized

by simply not being welcomed with enough love and care (1929), as well as

reactions of children to adult experiences they cannot represent in their

immature minds (1933). These ideas were rejected by Freud, to the level that

Ferenczi was declared psychotic and his papers forgotten/forbidden for about

half a century (Bonomi, 2004).

It seems that the concept of trauma has been polarizing psychoanalysts

during the entire century, constantly considered as opposite to the concept

of inner fantasy. On one side were Melanie Klein and her followers, who

thought that what mattered were mental drives, representations, anxieties, and

defense mechanisms, while social objects (like actual parents) were outside

the field of their interest. Opposite to them, the Independents, most explicitly

Donald Winnicott and John Bowlby, studied the importance of interpersonal

relationships and consequences of trauma (Dimitrijevic, 2011a). They started

with a joint paper that recommended the evacuation of whole families from

1939 London, so that children are not separated from their parents (Bowlby et

al., 1939), and kept studying trauma, albeit in different ways: Winnicott worked

as pediatrician and psychoanalyst, while Bowlby founded attachment theory

as a special form of object-relations theory, closer to natural sciences than to

psychoanalytic hermeneutics (Issroff, 2005).

Out of this grew many hypothesized types of trauma, several proposed

underlying mechanisms, many forms of treatment. By 1967, Anna Freud claimed

that the concept of trauma has become empty due to overuse. Although that was

still the time when psychodynamic model dominated psychiatry, especially in

the US, the situation there was much different. It now looks curious that the

widely used Kaplans Synopsis of Psychiatry has up to the 1980 edition relied

on a 1955 study that had claimed incest occurred in just one out of one million

American families (after Ross, 1996, pp. 67). And although current estimates are

more realistic, the division in approaches resembles that inside psychoanalysis.

288

SOCIOLOGIJA, Vol. LVII (2015), N 2

Namely, since the third revision, published in 1980, the Diagnostic and

Statistical Manual does not include discussions about possible causes of mental

disorders and this principle is included even in the generic definition offered

at the Manuals beginning. Without going into details of the possible critique

of this, it should be emphasized that there is one clear exemption to this rule.

The same DSM-III included (in the new category Anxiety Disorders) PostTraumatic Stress Disorders (PTSD), explicitly defined by their cause, and that

cause was trauma. One can reason that behind this is the now omnipresent

biological model of mental disorders (in all cases but PTSD, the causes is in the

dis-balance of neurotransmitters), which suits the pharmacological industry, and

that the role of trauma, and thus of more psychological models, is limited to just

one disorder (Lewis, 2006).

The best, and possibly the only, way to tell who is right and who is wrong

would be to see what research tells us about the incidence of trauma in general

population and in samples of persons with mental disorders. Luckily, we have

more and more solid data about this.

Incidence of trauma

So, is trauma very rare, as we used to believe, or could it be that it is

everywhere around us? And: is it more frequent in the lives and growing up of

the persons with mental disorders?

We can decide on these issues now based on several large-scale

epidemiological studies, mostly done in the United States. In general, it seems

that high incidence of early individual trauma seems not to be disputed in

contemporary scientific literature. In contrast to the 1955 study quoted above,

for instance, more recent estimates claim that there are approximately one

million cases of child abuse and neglect substantiated in the US each year (US

Department of Health, 2005, www.acf.hhs.gov). And we have even more precise

data, showing the incidence of various types of trauma in percentage:

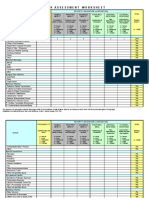

Table 1. Incidence of different types of trauma

in general population (adapted after: Putnam et al., 2015)

Sample size

Type of abuse

Physical abuse

Sexual abuse

Emotional abuse

Women

N=9367

Men

N=7970

Total

N=17337

27

24.7

13.1

29.9

16

7.6

28.3

20.7

10.6

The table shows that the incidence rate changes for different types of trauma,

but is constantly alarmingly high. This impressively large sample shows that in

some cases one quarter or even a third of the subjects were exposed to trauma,

with strong gender differences (e.g., there are more physically abused men, but

more sexually abused women). From this, we cannot make conclusions about

the difference between general and clinical populations, but we will return to

289

Aleksandar Dimitrijevic: Trauma as a neglected etiological factor of mental disorders

that shortly. It seems, however, that we have learned that trauma occurs very

frequently in contemporary Western society.

How about cumulative trauma? Is it frequent that the same child gets

molested or exposed to witnessing trauma2 more than once? Here is data from

the same sample:

Table 2. Cumulative incidence of trauma

in general population (after: Putnam et al., 2015)

Sample size

0

1

2

3

4 or more

Women

N=9367

34.5

24.5

15.5

10.3

15.2

Men

N=7970

38

27.9

16.4

8.6

9.2

Total

N=17337

36.1

26

15.9

9.5

12.5

We can be relieved about the almost two fifths of the population who have

grown up without serious trauma. The problem may be, however, important for

the majority, at 63.9%, have been traumatized. Worse still, among them as many

as 37.9% were traumatized more than once, and every eighth subject had adverse

experiences repeatedly (four or more times). This study would, thus, suggest that

there are almost twice more traumatized than non-traumatized individuals and

that almost two fifths of the general population (or, in real numbers, millions

and millions of adults) suffered repeatedly.

To make the matters more worrisome, empirical evidence shows that most

maltreatment happens in the earliest childhood, when it has greater negative

effects on developing mind and brain. The troubling 5.7% children of ages 03

experience trauma or neglect, which is, happily, followed by a steady decline, to

reach 1.9% at the age 1617 (US Department of Health and Human Services,

2014).

Another important question may well be where all this takes place. How

frequent is family trauma?

Table 3. Incidence of family dysfunctions

in general population (after: Putnam et al., 2015)

Sample size

Type of household dysfunction

Substance abuse

Parental separation or divorce

Mental illness

Mother treated violently

Incarcerated member

Women

N=9367

Men

N=7970

Total

N=17337

29.5

24.5

23.3

13.7

5.2

23.8

21.8

14.8

11.5

4.7

26.9

23.3

19.4

12.7

5.1

Data in this table report adverse childhood experiences (ACES)

family dysfunction.

trauma, neglect and

290

SOCIOLOGIJA, Vol. LVII (2015), N 2

We see, again, that the incidence is disturbingly high, and especially for

women. Every fifth subject has experienced at least one type of household

dysfunction, sometimes the rate is higher, and for some it must have been more

than one. It is also significant that four out of five types of the listed family

disfunctions actually make parents emotionally unavailable: substance abuse,

divorce, mental illness and incarceration (this one does not have to involve the

parent, though).3

Based on all this evidence, which comes from recent studies on large samples,

we can conclude that trauma is a widespread phenomenon and that it frequently

happens to infants and preschool children, inside their homes. But, what are the

consequences of trauma? Does this evidence bear clinical importance?

Consequences of childhood trauma

Many clinical psychologists have, in studies of various types, found that

consequences of childhood trauma include and are not limited to the following

(see Lieberman & Van Horn, 2011; Osofsky, 2011):

more frequent adoptions, child fatalities, developmental delays;

poor attachment and socialization, low self-esteem;

distortions in sensory perception and meaning, constrictions in action,

deficits in readiness to learn, attention, abstract reasoning and executive

function;

HPA/cortisol dysregulation, smaller frontal lobe volume, asymmetry of

left and right brain centers included in the cognitive processes of language

production.

It is also found that prevalence of many serious somatic conditions correlates

positively with the number of traumatic events, like Ischemic Heart Disease,

Stroke, Diabetes, and especially Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease and

Sexually Transmitted Diseases (Felitti et al., 1998).

Besides developmental and health issues, trauma is especially important for

the field of mental health care. Strong positive correlations were found between

the number of traumatic events and several types of mental disorders:

If we consider tables 1&3 together, we may come to the conclusion that many adults report

being traumatized as well as many report coming from dysfunctional families. We do not

know whether these are the same individuals, but it is quite probable that they are. In case

this really is true, it would mean that children cannot get support from their parents when

they need it most.

Aleksandar Dimitrijevic: Trauma as a neglected etiological factor of mental disorders

291

Figure 1 Correlation between number

of traumatic events and mental disorders

(Adapted after: Putnam et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2005)

Colleagues gathered in the International Society for Psychological and Social

Approaches to Psychosis (www.isps.org) have prepared reviews of more than

40 research studies about trauma and psychotic disorders conducted between

1984 and 2003 (Read et al., 2004). Clinical samples included in the meta-analysis

ranged between 7 and 321 and included: persons with schizophrenia; persons

with other psychoses; outpatient samples in which at least 50% of subjects were

persons with psychotic disorders; child and adolescent inpatients. I have used

their work to draw a simple table that compares frequencies of trauma in general

population and among psychiatry patients.

Table 4. Frequency of childhood trauma among adults

with mental disorders (after: Read et al., 2004)

Physical abuse

Sexual molestation

Incest

Parental loss

General population

3% of men

5% of women

Psychiatry patients

30% of men

3442% of women

3% of men

12% of women

7% of men

1317% of women

18% of men

51% of women

62% of men

62% of women

38% of patients with SCH

17% of patients with BAD

I believe that the table clearly illustrates that certain forms of early individual

trauma are 410 times more frequent among our patients than in general

populations (although values for the latter are much lower than in the studies

performed in the US). This is further underlined by comparison studies that

established differences between psychotic patients with the history of childhood

292

SOCIOLOGIJA, Vol. LVII (2015), N 2

trauma and those without it (Read et al., 2004, p. 223), which resulted in the

finding that the consequences of childhood trauma are associated with:

more self-mutilation, higher symptom severity, more suicide attempts;

earlier first admissions;

more medication;

longer and more frequent hospitalizations and seclusions.

We can, thus, plausibly conclude, based on many international studies and

meta-analyses, that trauma is far more frequent among persons who experience

somatic or mental health problems. We still have to wonder, however, whether

these correlations indicate causal relationships or not.

Attachment trauma

One type of trauma has in recent studies been emphasized as specially

important and that is attachment trauma.4 Consequences seem to be most

disturbing when trauma is inflicted in closest relationships, those from which

children expect safety and encouragement for exploration. Children exposed to

attachment trauma frequently develop the so-called disorganized attachment

pattern, characterized by complete lack of strategy in close relationships, freezing

out of movement and expression, and/or incomprehensible behavior. About 15%

of children in non-clinical samples are classified as disorganised (Van Ijzendoorn

& Bakermans-Kranenburg, 1997, p. 136), but this number raises to astonishing

82% of maltreated children (Lyons-Ruth & Jacobvitz, 1999, p. 526).

There is obvious connection between the disorganized attachment in

children and their parents mental health status. Most mothers suffering from

depression and schizophrenia, and about 80% of mothers with anxious disorders,

have insecurely attached children (Greenberg, 1999, p. 478). More than a half of

D-children have parents who had suffered significant loss(es) two years before

the childrens birth that are still unresolved (Lyons-Ruth & Jacobvitz, 1999, pp.

5289, 540; Van Ijzendoorn & Bakermans-Kranenburg, 1997, p. 136).

Disorganized attachment pattern at the age of 12 months, based very

frequently on attachment trauma, is predictive of the following set of variables

(based on Greenberg, 1999, p. 479; Solomon & George, 1999, p. 294):

controlling, pseudo-parental behavior in preschool years;

aggressive behavior in 83% of 7-year-olds;

problems with adaptation to school in majority of these children;5

delinquency, addictions, and personality disorders in majority of these

adolescents;

Another form that is attracting more attention is social or genocidal trauma, but it cannot

be discussed properly here for the lack of space. For detailed review see Delic et al., 2014;

Hamburger, in press.

Recent empirical data about the relationship between attachment and cognition can be found

in Banjac et al., 2013; Dimitrijevic et al., 2013.

Aleksandar Dimitrijevic: Trauma as a neglected etiological factor of mental disorders

293

mental health problems in about 80% of these adults, and especially dissociative

phenomena and disorders.

One additional benefit from attachment research is that we now have

empirical evidence substantiating and nuancing our understanding of the

mechanisms that lead from trauma to disorganized attachment to deviant

behavior and mental disorder.

Attachment theory predicted that trauma would inhibit investigation and

heighten the need for comfort coming from the secure attachment base (Bowlby,

1988), and this was indeed corroborated. Furthermore, it was found that

traumatized children move toward parents and at the same time away from them

and are forced to create multiple models of caregivers (Fonagy & Target, 2008).

Faced with the situation in which, for instance, the father, supposed or until

recently actual source of comfort and love, starts abusing him or her, the child

may unconsciously decide to sacrifice his or her own mind in order to save the

representation of the father. Such is the importance of the parent for the highly

dependent preschooler that it is easier to lose ones own inner world, because

children survive without introspective capacity, but vanish without adults. These

children may split in their minds two types of experiences with parents: loving

father from abusive father. There is, then, one part of themselves they do not dare

admit even to themselves, one part to horrible to face. The traumatized child

first defensively inhibits her capacity to mentalize, trying to avoid the insight

that the parent may wish to hurt her (Fonagy et al., 1997, p. 253). Consequently,

trauma impedes deeper procession of emotional experiences, and interferes with

the (further) development of mentalizing capacity or can even destroy it (Fonagy

et al., 2002).6 This experience may generalize and the child then feels that

looking inside is dangerous under any circumstances. Being unaware of inner

psychological processes means, of course, that you cannot control or regulate

them. Exactly this is considered to lead not only to the disorganized attachment,

which is not a pathological condition per se, but to the later dissociative disorders

(Liotti, 2004) as well as Borderline Personality Disorder (Allen & Fonagy, 2006).

It is even more beneficial that we can use this research evidence to propose

prevention and psychotherapy interventions for disorders caused by trauma.

Treatment of (attachment) trauma

This evidence cannot but motivate us to look for ways to prevent trauma

or treat its consequences. Sceptics, if they exist, are often reminded about the

costs: The US spend about $1.8 Million per victim of early trauma in order to

deal with the consequences of child abuse, teen pregnancy, high school dropout,

illegal drug and alcohol abuse (Pew Issue Brief, 2011); estimated lifetime costs

for all those who in 2014 were victimized for the first time will be $5.9 Trillion

(The Perryman Group, 2014).

6

Attachment trauma can also interfere with ethical development and development of empathy.

For a detailed review see Milojevi & Dimitrijevi, 2012, and for empirical data see Milojevi

& Dimitrijevi, 2014.

294

SOCIOLOGIJA, Vol. LVII (2015), N 2

Luckily, effective prevention and treatment programs exist.7 Meta-analysis

of 70 studies with 88 different interventions, 7,636 parents and 1,503 children

revealed that there was a small but significant improvement ONLY when

programs were focused on improving parental capacity to accurately perceive

and translate social signals contained in the infants and childrens non-verbal

signals (Bakermans-Kranenburg, van Ijzendoorn, & Juffer, 2003). Frame-byframe analysis shows that maternal reactions of smiling, surprise, withdrawal

or looking away to the signs of four-months-old infants distress are predictive

of disorganized attachment, or even that differences between facial and vocal

emotional expressions are predictive of adults dissociation (Beebe et al., 2010).

On the basis of this, several programs were developed that use video-taping

of parent-infant interaction and subsequent discussion with parents aimed at

improving their sensitivity.

It seems, however, that improvement may come even from far less

sophisticated issues. For instance, successful public advocacy of positive parental

skills should be effective, as we have evidence showing that while cumulative

trauma and resilience are negatively correlated, positive childhood experiences

can counteract negative ones (Lieberman et al., 2005). These might include such

broad categories as parental devotion, emotional availability8 and behavioral

predictability (see Winnicott, 1960), but also more specific ones like the positive

influence of coherence and mentalizing nature of general discourse at home

(Fonagy & Bateman, 2008, p. 145). It turns out that children who grow up in

families where emotions are a topic the parents frequently talk and think together

develop faster and better in terms of theory of mind and mentalization; the

same goes for situations in which mothers ascribe psychological features to their

six-months-old babies (Fonagy & Bateman, 2008, p. 145). And where there is

mentalization, effects of trauma cannot be too bad.

Several studies conducted at the University of Leiden, Holland, confirmed

that most disorganized children have mothers with severe trauma and/or loss

they were unable to overcome, so they behave frighteningly or frightfully, and

are both the source of and the solution for the childrens anxiety, found also who

are the most helpful parents. The results showed that securely attached childrens

mothers do not suffer from unintegrated trauma, but are not particularly helpful

in extreme situations, possibly because they lack personal experience of this

kind. On the other hand, autonomously attached women who had experienced

significant loss(es) that they managed to overcome (labeled Earned Secure, as

opposed to Continuous Secure) were able to show the lowest frequency and

intensity of frightening or frightful behavior, and proved to be most helpful to

their children. Due to their experiences of both traumatization and overcoming

it, these mothers, more or less unconsciously, know what their children need and

how to provide that (after Coates, 1998, pp. 299300).

7

8

The always pragmatic Americans have counted that child abuse prevention programs return

$3, and Parent Child Interaction Therapy $3.64 to every $1 invested (Lieb et al., 2004).

On detrimental effects of parental emotional non-involvement see Fonagy & Bateman, 2008,

p, 145.

Aleksandar Dimitrijevic: Trauma as a neglected etiological factor of mental disorders

295

This lead many authors to come up with a very specific etiological hypothesis.

It is now believed that the cause of many mental disorders is a combination of:

a) severe and/or repeated childhood trauma, and b) lack of a person who could

provide the intersubjective foundation for mentalizing. Trauma, thus, does not

have to lead to a mental disorder and will not do so in cases when there are

adults ready to face and recognize childs traumatic experience and offer help in

thinking about and overcoming it (Fonagy, 2000; Levine, 2014).

For many children, unfortunately, benevolent, emotionally available and

mentalizing adults are not present in their social world, and preventive programs

have not reached many others. It is highly likely, as we have seen above, that they

will develop one or several forms of somatic illnesses, deviant behaviors and/

or mental disorders. And it is for them that we need to come up with treatment

procedures. While noumerous psychotherapy variations are considered applicable

for work with victims of trauma, at least one is developed especially for them.

The so called Mentalization Based Treatment is being formulated over the last

decade or so, with all the above mentioned principles in mind (e.g., Bateman &

Fonagy, 2006; for a review see Dimitrijevi, 2011b). Initially aimed at persons

with Borderline Personality Disorder, it is a manualized, short-term treatment,

that should help clients acquire capacity and skill of mentalization. They are first

faced with many questions that should help them realize how much of the inner

and social world they are or have been taking for granted. Subsequently, they

should hopefully start understanding their own and other persons behaviors in

terms of intentional mental states. A randomized control trial has shown that

MBT is highly effective in the follow up after 42 months (Fonagy & Bateman,

2008): patients needed less medication and fewer and shorter hospitalizations,

referred less self-harming and suicidal behavior, and improved educationally and

professionally.

Conclusion

In the last half century, the biological model of mental disorders, and

especially the psychotic ones, has gained such prevalence that discussing anything

but genes, dopamine, and cerebral ventricles is considered obsolete and nonscientific. There were various forms of resistance to admitting the importance of

trauma, including tendency that the best-selling textbooks report about trauma

in a misconceived and one-sided way (Brand & McEwan, 2015). It was only in

recent times that enough evidence was gathered to make it even more obvious

that trauma plays an important role in both development and clinically relevant

conditions of a huge number of children and adults.

The most troubling aspect of this situation, however, is not denial of the

importance of trauma, but the ensuing impossibility for persons with mental

disorders to get what they need at the institutions that are meant to provide help.

Traumatized persons are more often hospitalized than non-traumatized persons

with mental disorders (Read et al., 2004), yet many of them get nothing but

disappointment and conviction that help cannot be found, looking for the fault

296

SOCIOLOGIJA, Vol. LVII (2015), N 2

in themselves or allegedly incurable diseases instead of at the re-traumatizing

nature of depersonalized institutions (see Dimitrijevic, in press).

For all these reasons, the frequency and the role of trauma in the onset of

various somatic and mental disorders have to be advocated and substantiated, and

prevention and therapy of its consequences further developed. Otherwise, the world

will remain full of unheard, unrecognized and wrongly treated victims of peace.

Acknowledgements:

The preparation of this paper was supported by Ministry of Education and

Science of the Republic of Serbia, Grant No. 179018, and by Trauma, Trust, and

Memory Project funded by German Academic Exchange Service [DAAD],

Grant No. 57173352.

References:

Allen, J. G., & Fonagy, P. (Eds.). (2006). The handbook of mentalization-based

treatment. John Wiley & Sons.

Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., Van Ijzendoorn, M. H., & Juffer, F. (2003). Less

is more: meta-analyses of sensitivity and attachment interventions in early

childhood. Psychological Bulletin, 129(2), 195.

Banjac, S., Altaras Dimitrijevi, A., & Dimitrijevi, A. (2013). Odnos vezanosti,

mentalizacije i inteligencije u uzorku srednjokolaca. Psiholoka istraivanja,

16(2), 175190.

Bateman, A. & P. Fonagy (2008): 8-Year Follow-Up of Patients Treated for

Borderline Personality Disorder: Mentalization-Based Treatment Versus

Treatment as Usual. American Journal of Psychiatry, 165, 5, 631638.

Bateman, A. W., & Fonagy, P. (Eds.). (2012). Handbook of mentalizing in mental

health practice. American Psychiatric Publishers.

Beebe, B., Jaffe, J., Markese, S., Buck, K., Chen, H., Cohen, P., & Feldstein, S.

(2010). The origins of 12-month attachment: A microanalysis of 4-month

motherinfant interaction. Attachment & Human Development, 12(12),

3141.

Bonomi, C. (2004). Trauma and the symbolic function of the mind. International

Forum of Psychoanalysis, 13, 12, 4550.

Bonomi, C. (2015). The Cut and the Building of Psychoanalysis, Volume I:

Sigmund Freud and Emma Eckstein. Routledge.

Bowlby, J. (1988). A secure base: Clinical applications of attachment theory. Taylor

& Francis.

Bowlby, J., Miller, E., & Winnicott, D. W. (1939). Evacuation of small children.

British Medical Journal, 2(4119), 1202.

Brand, B. L. & McEwan, L. E. (2014). Coverage of CHILD Maltreatment and

Its Effects in Three Introductory Psychology Textbooks. Trauma Psychology

News, 9(3).

Aleksandar Dimitrijevic: Trauma as a neglected etiological factor of mental disorders

297

Coates, S. (1998): Having a Mind of Ones Own and Holding the other in

Mind: Commentary on Paper by Peter Fonagy and Mary Target (1998).

Psychoanalytic Dialogues, 8, str. 115148.

Deli, A., Hasanovi, M., Avdibegovi, E., Dimitrijevi, A., Hancheva, C., Scher,

C., Stefanovic-Stanojevic, T., Streeck-Fischer, A., & Hamburger, A. (2014).

Academic model of trauma healing in post-war societies. Acta medica

academica, 43(1), 7680.

Dimitrijevic, A. (2011a). Bindung und Phantasie in einer psychoanalytischen

Behandlung. Journal fuer Psychoanalyse, 31, 52, 84100.

Dimitrijevi, A. (2011b). Pregled naela tretmana zasnovanog na

mentalizovanju. Psihijatrija danas, 43, 1, 520.

Dimitrijevic, A. (in press). Psychiatric Treatment as a Form of Social Trauma. In

A. Hamburger (ed.), Trauma, Trust, Memory. Psychoanalytic Approaches to

Social Trauma. Karnac Books.

Dimitrijevi, A., Altaras Dimitrijevi, A., & Joli Marjanovi, Z. (2013). An

examination of the relationship between intelligence and attachment in

adulthood. In C. Pracana & L. Silva (Eds.), InPACT 2013 International

Psychological Applications Conference and Trends. Book of proceedings (pp.

2125). Lisbon: World Institute for Advanced Research and Science.

Ellenberger, H. F. (2008). The discovery of the unconscious: The history and

evolution of dynamic psychiatry. Basic Books.

Felitti, V. J., Anda, R. F., Nordenberg, D., Williamson, D. F., Spitz, A. M.,

Edwards, V., & Marks, J. S. (1998). Relationship of childhood abuse and

household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The

Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. American Journal of Preventive

Medicine, 14(4), 245258.

Ferenczi, S. (1929). The unwelcome child and his death-instinct. International

Journal of Psycho-Analysis, 10, 125129.

Ferenczi, S. (1933/1949): Confusion of Tongues between the Adult and the Child.

International Journal of Psycho-Analysis, 30, 225230. Originally published in

1933.

Fonagy, P. (2000): Attachment and Borderline Personality Disorder. Journal of

the American Psychoanalytic Association, 48, 4, 11291146.

Fonagy, P., G. Gergely, E. L. Jurist & M. Target (2002): Affect Regulation,

Mentalization and the Development of the Self. New York, NY: Other Press.

Fonagy, P. & M. Target (2008). Attachment, Trauma, and Psychoanalysis. Where

Psychoanalysis Meets Neuroscience. In E. L. Jurist, A. Slade & S. Bergner

(eds) Mind to Mind. Infant Research, Neuroscience, and Psychoanalysis (pp.

1549). New York: Other Press.

Fonagy, P., M. Target, M. Steele, H. Steele, T. Leigh, A. Levinson & R. Kennedy

(1997): Morality, disruptive behavior, borderline personality disorder, crime,

and their relationship to security of attachment. In L. Atkinson & K. J. Zucker

(eds.) Attachment and psychopatology (pp. 223274). New York: Guilford.

298

SOCIOLOGIJA, Vol. LVII (2015), N 2

Freud, A. (1967). Comments on trauma. In S. Furst (ed.), Psychic Trauma (pp.

235246). New York: Basic Books.

Greenberg, M. T. (1999): Attachment and Psychopathology in Childhood. U: J.

Cassidy & P. R. Shaver (ur.) Handbook of Attachment. Theory, Research and

Clinical Applications (pp. 469496). New York & London: The Guilford Press.

Hacking, I. (1998). Rewriting the soul: Multiple personality and the sciences of

memory. Princeton University Press.

Hamburger, A. (in press): Genocidal Trauma. Individual and Social Consequences

of the Assault on the Mental and Physical Life of a Group. In: A. Hamburger

& D. Laub (eds.), Psychoanalytic Approaches to Social Trauma and Testimony:

Unwanted Memory and Holocaust survivors. London: Routledge.

Hesse, E. (1999): Adult Attachment Interview: Historical and Current

Perspectives. In J. Cassidy & P. R. Shaver (eds.) Handbook of Attachment.

Theory, Research and Clinical Applications (pp. 395433). New York &

London: The Guilford Press.

Issroff, J. (2005). Donald Winnicott and John Bowlby: Personal and Professional

Perspectives. London: Karnac Books.

Levine, H. (2014). Psychoanalysis and trauma. Psychoanalytic Inquiry, 34:214224.

Lewis, B. (2006): Moving Beyond Prozak, DSM, and the New Psychiatry. The Birth

of Postpsychiatry. Ann Arbor, MI: The University of Michigan Press.

Lieb, R., Mayfield, J., Miller, M., & Pennucci, A. (2004). Benefits and costs of

prevention and early intervention programs for youth (No. 0407, p. 3901).

Olympia, WA: Washington State Institute for Public Policy.

Lieberman, A. F., Padrn, E., Van Horn, P., & Harris, W. W. (2005). Angels in

the nursery: The intergenerational transmission of benevolent parental

influences. Infant mental health journal, 26(6), 504520.

Lieberman, A. F., & Van Horn, P. (2011). Psychotherapy with infants and young

children: Repairing the effects of stress and trauma on early attachment.

Guilford Press.

Liotti, G. (2004). Trauma, dissociation, and disorganized attachment: Three

strands of a single braid. Psychotherapy: Theory, research, practice, training,

41(4), 472.

Lyons-Ruth, K. & Jacobvitz, D. (1999). Attachment Disorganization: Unresolved

Loss, Relational Violence, and Lapses in Behavioral and Attentional Strategies.

In J. Cassidy & P. R. Shaver (eds.) Handbook of Attachment. Theory, Research

and Clinical Applications (pp. 520554). New York & London: The Guilford

Press.

Makari, G. (2008). Revolution in mind: The creation of psychoanalysis. New York:

HarperCollins.

Masson, J. (ed.) (1985). The Complete Letters of Sigmund Freud to Wilhelm Fliess,

18871904. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

Masson, J. (1992). The assault on truth: Freud and child sexual abuse. London:

Fontana.

Aleksandar Dimitrijevic: Trauma as a neglected etiological factor of mental disorders

299

Milojevi, S. & Dimitrijevi, A. (2012). Socioemocionalni model maloletnike

delinkvencije. Engrami, 34 (4), 7185.

Milojevi, S. & Dimitrijevi, A. (2014). Empathic capacity in convicted delinquent

minors. Psihologija, 47(1), 6579. DOI: 10.2298/PSI1401065M.

Osofsky, J. D. (Ed.). (2011). Clinical work with traumatized young children.

Guilford Press.

Paying later: High cost of failing to invest in young children. 2011. Pew Issue

Brief.

Putnam, K. T., Harris, W. W., & Putnam, F. W. (2013). Synergistic childhood

adversities and complex adult psychopathology. Journal of traumatic stress,

26(4), 435442.

Putnam, K. T., Harris, W. W., & Putnam, F. W., Lieberman, A., & Amaya-Jackson,

L. (2015). Oportunities to change the outcomes of traumatized children.

Downloaded from CANarratives.org.

Read, J., Mosher, L. R., & Bentall, R. P. (Eds.) (2004). Models of madness:

Psychological, social and biological approaches to schizophrenia. Psychology

Press.

Ross, C. A. (1996). History, Phenomenology, and Epidemiology of Dissociation.

In L. K. Michelson & W. J. Ray (eds.) Handbook of Dissociation. Theoretical,

Empirical, and Clinical Perspectives (pp. 324). New York London: Plenum

Press.

Solomon J. & C. George (1999). The Measurement of Attachment Security in

Infancy. In J. Cassidy & P. R. Shaver (eds.) Handbook of Attachment. Theory,

Research and Clinical Applications (pp. 287316). New York & London: The

Guilford Press.

The Perryman Group. (2014). Suffer the Little Children: An Assessment of the

Economic costs of Child Maltreatment. http://perrymangroup.com/specialreports/child-abuse-study/

US Department of Health and Human Services. (2014). Child Maltreatment

2012. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services.

Van Ijzendoorn, M. H. & M. J. Bakermans-Kranenburg (1997). Intergenerational

Transmission of Attachment: A Move to the Contextual Level. In L. Atkinson

& K. J. Zucker (eds.) Attachment and Psychopathology (pp. 135170). New

York & London: The Guilford Press.

Wang, P. S., Lane, M., Olfson, M., Pincus, H. A., Wells, K. B., & Kessler, R. C.

(2005). Twelve-month use of mental health services in the United States:

results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of general

psychiatry, 62(6), 629640.

Winnicott, D. W. (1975). Primary Maternal Preocupation. In Through Paediatrics

to Psycho-Analysis (pp. 300305). London: Hogarth Press & Institute of

Psychoanalysis.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- 1 Forthyron Pi 200 400 en PDFDocument1 page1 Forthyron Pi 200 400 en PDFjohnybarNo ratings yet

- NCPDocument14 pagesNCPclaidelynNo ratings yet

- Lab Exercise 5Document3 pagesLab Exercise 5Yeong-Ja KwonNo ratings yet

- Subjective: Diarrhea Related To Watery Short Term: IndependentDocument4 pagesSubjective: Diarrhea Related To Watery Short Term: IndependentEmma Lyn SantosNo ratings yet

- Geria NCPDocument4 pagesGeria NCPBrylle CapiliNo ratings yet

- Menstrual Blood Derived Stem Cells and Their Scope in Regenerative Medicine A Review ArticleDocument6 pagesMenstrual Blood Derived Stem Cells and Their Scope in Regenerative Medicine A Review ArticleInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- What Is Malnutrition?: WastingDocument6 pagesWhat Is Malnutrition?: WastingĐoan VõNo ratings yet

- Mapeh: Music - Arts - Physical Education - HealthDocument23 pagesMapeh: Music - Arts - Physical Education - HealthExtremelydarkness100% (1)

- Malawi Clinical HIV Guidelines 2019 Addendumversion 8.1Document28 pagesMalawi Clinical HIV Guidelines 2019 Addendumversion 8.1INNOCENT KHULIWANo ratings yet

- ZFN, TALEN, and CRISPR-Cas-based Methods For Genome EngineeringDocument9 pagesZFN, TALEN, and CRISPR-Cas-based Methods For Genome EngineeringRomina Tamara Gil RamirezNo ratings yet

- Kelseys ResumeDocument1 pageKelseys Resumeapi-401573835No ratings yet

- 2018 Surgical Rescue in Medical PatientsDocument11 pages2018 Surgical Rescue in Medical PatientsgiseladlrNo ratings yet

- National Geographic USA - January 2016Document148 pagesNational Geographic USA - January 2016stamenkovskib100% (4)

- The Nadi Vigyan by DR - Sharda Mishra MD (Proff. in Jabalpur Ayurved College)Document5 pagesThe Nadi Vigyan by DR - Sharda Mishra MD (Proff. in Jabalpur Ayurved College)Vivek PandeyNo ratings yet

- Lesson 5 Core Elements Evidenced Based Gerontological Nursing PracticeDocument38 pagesLesson 5 Core Elements Evidenced Based Gerontological Nursing PracticeSam GarciaNo ratings yet

- Liver Meeting Brochure 2016 PDFDocument4 pagesLiver Meeting Brochure 2016 PDFManas GhoshNo ratings yet

- Nursing Care of The Client With High-Risk Labor & DeliveryDocument10 pagesNursing Care of The Client With High-Risk Labor & DeliveryWilbert CabanbanNo ratings yet

- SNB Exam Sample Question Paper 2Document19 pagesSNB Exam Sample Question Paper 2Ketheesaran LingamNo ratings yet

- IC Risk Assessment Worksheet - Kangas-V2.1-Aug.2010 1Document4 pagesIC Risk Assessment Worksheet - Kangas-V2.1-Aug.2010 1Juon Vairzya AnggraeniNo ratings yet

- Orthobullets Foot and AnkleDocument88 pagesOrthobullets Foot and AnkleStevent Richardo100% (1)

- Sample Chapter of Assessment Made Incredibly Easy! 1st UK EditionDocument28 pagesSample Chapter of Assessment Made Incredibly Easy! 1st UK EditionLippincott Williams and Wilkins- Europe100% (1)

- Angina PectorisDocument17 pagesAngina PectorisRakesh Reddy100% (1)

- Gut Health Guidebook 9 22Document313 pagesGut Health Guidebook 9 2219760227No ratings yet

- Pathophysiology of Ischemic Stroke FinalDocument3 pagesPathophysiology of Ischemic Stroke FinalAcohCChao67% (3)

- Anatomi & Fisiologi Sistem RespirasiDocument57 pagesAnatomi & Fisiologi Sistem RespirasijuliandiNo ratings yet

- Páginas de Rockwood Fraturas em Adultos, 8ed3Document51 pagesPáginas de Rockwood Fraturas em Adultos, 8ed3Estevão CananNo ratings yet

- Fertilization Reflection PaperDocument2 pagesFertilization Reflection PaperCrisandro Allen Lazo100% (2)

- PowersDocument14 pagesPowersIvan SokolovNo ratings yet

- Resveratrol and Its Effects On Human Health and LongevityDocument367 pagesResveratrol and Its Effects On Human Health and LongevityArnulfo Yu LanibaNo ratings yet

- Complications and Failures of ImplantsDocument35 pagesComplications and Failures of ImplantssavNo ratings yet