Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Weight Loss With A Modified Mediterranean-Type Diet Using Fat Modification A Randomized Controlled Trial.

Uploaded by

antonioOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Weight Loss With A Modified Mediterranean-Type Diet Using Fat Modification A Randomized Controlled Trial.

Uploaded by

antonioCopyright:

Available Formats

European Journal of Clinical Nutrition (2015), 17

2015 Macmillan Publishers Limited All rights reserved 0954-3007/15

www.nature.com/ejcn

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Weight loss with a modied Mediterranean-type diet using fat

modication: a randomized controlled trial

A Austel, C Ranke, N Wagner, J Grge and T Ellrott

BACKGROUND/OBJECTIVES: There is evidence that Mediterranean diets with a high proportion of olive oil and nuts can be

effective for weight management and prevention of cardiovascular disease. It might be difcult for populations with other eating

habits to follow such diets. Therefore, a modied Mediterranean-type diet using fat modication through neutral and butteravored canola oil, walnuts and walnut oil with two portion-controlled sweet daily snacks was tested in Germany.

SUBJECTS/METHODS: Randomized waiting-list control study with overweight/grade 1 obese subjects: 12-week self-help modied

Mediterranean-type diet, 6 weeks of diet plans and 6 weeks of weight loss maintenance training. Trial duration was 12 months.

Intervention group (IG) included 100 participants (average age of 52.4 years, weight 85.1 kg and body mass index (BMI) 30.1 kg/m2),

waiting-list control group (CG) included 112 participants (52.6 years, 84.1 kg and 30.1 kg/m2).

RESULTS: Per-protocol weight loss after 12 weeks was 5.2 kg in IG vs 0.4 kg in CG (P 0.0001), BMI 1.8 vs 0.1 kg/m2 (P 0.0001),

waist circumference 4.7 vs 0.9 cm (P 0.0001). Triglycerides, total cholesterol and LDL cholesterol improved signicantly in IG

but not in CG. One-year dropouts: 44% in IG and 53% in CG. Weight loss after 12 months: 4.2 kg (pooled data).

CONCLUSION: A ve-meal modied Mediterranean-type diet with two daily portion-controlled sweet snacks was effective for

weight management in a self-help setting for overweight and grade 1 obese subjects. Fat modication through canola oil, walnuts

and walnut oil improved blood lipids even at 12 months.

European Journal of Clinical Nutrition advance online publication, 18 February 2015; doi:10.1038/ejcn.2015.11

INTRODUCTION

The increasing prevalence of overweight and obesity is one of the

main health problems of our time. According to the German

National Consumption Survey II1 in 2006, almost two-third of the

German men and half of the German women had a body mass

index (BMI) higher than 25 kg/m2, therefore being at least

overweight. It was found that 20.5% of men and 21.2% of women

in Germany were obese (BMI430 kg/m2). Recently published

results of the DEGS1 (Studie zur Gesundheit Erwachsener in

Deutschland 1) study show only a slight rise between 2006 and

2011 in the overall percentage of persons with a BMI 425 kg/m2, but

an increase of obesity to 23.3% (men) and 23.9% (women) in the

German population.2 Long-acting approaches to prevention and

therapy, complying with quality criteria established by scientic

societies as international and national guidelines, have to be

developed, evaluated and tailored to meet the needs of different

population groups and categories of obesity.3 Most current

guidelines suggest professional treatment options including diet,

increased physical activity and behavior modication.47

The 2014 guidelines of the German Obesity Society4 recommend

several dietary options: reduction of fat or carbohydrates (step 1),

combined reduction of fat and carbohydrates (step 2), meal

replacements with formula products (step 3) and low-energy

formula diets (step 4). Mediterranean diets for weight loss could

be dened as a variation of step 2 in the recommended dietary

options. A high proportion of dietary fat is provided by olive oil and

nuts. Studies showed that these diets are an equally or more

effective strategy for weight management.8,9 Furthermore, it could

be shown in the PREDIMED (PREvencin con DIeta MEDiterrnea)

trial that Mediterranean diets reduce the cardiovascular mortality.10

A main problem in dietary management of obesity is long-term

compliance.11,12 It is probable that compliance diminishes if diets

are too restrictive, too inconvenient and/or too different from the

usual eating behavior. Mediterranean diets differ from the eating

habits in central or northern Europe, where it is not olive oil and

nuts but butter and animal fat that are the most relevant sources

of dietary fat.13 In those countries, a sustainable dietary strategy

for weight management has to reect eating habits established

over decades. It has to offer easy changes not too far from those

habits. The New Nordic diet is an example for a compromise

between local eating habits in northern Europe and benets

derived from Mediterranean diets.14,15

In this study, we tested a ve-meal modied Mediterraneantype diet for weight management using fat modication through

neutral canola oil, butter-avored canola oil, walnuts and walnut

oil with two portion-controlled sweet daily snacks for men and

women with a BMI between 25 and 35 kg/m2 in a self-help setting

(provision of material only, no counseling). The modied

Mediterranean-type diet did not exclude tasty and convenient

foods like pizza or sweet snacks (chocolate, ice-cream and cake).

According to Fletcher et al.,16 a rigid exclusion creates cravings

for those foods. Massey and Hill17 found that food cravings are

signicantly more frequent among dieters than among nondieters, the most craved food being forbidden foods. This might

corrupt long-term sustainability of such diets.

To make the modied Mediterranean-type diet convenient and

suitable for daily use, its recipes were relatively simple and timesaving both in the purchase of goods (foods could be bought in

standard supermarkets at reasonable prices) and in cooking.

Institute for Nutrition and Psychology at Gttingen University Medical School, Gttingen, Germany. Correspondence: A Austel, Institut fr Ernhrungspsychologie, Humboldtallee 32,

Gttingen 37073, Germany.

E-mail: anjaaustel@med.uni-goettingen.de

Received 12 August 2014; revised 19 December 2014; accepted 23 December 2014

Weight loss with a modied Mediterranean-type diet

A Austel et al

2

To optimize the metabolic effects, intake of saturated and

transunsaturated fatty acids was reduced and intake of monounsaturated fatty acids and omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids

was increased.

Intervention consisted of 6 weeks of diet plans to optimize

initial weight loss and 6 weeks of training in weight loss

maintenance strategies to improve long-term weight stabilization

under ad libitum conditions. Results were obtained at 12 and

52 weeks.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

Subjects

Two hundred and twenty-ve overweight and grade 1 obese subjects (BMI

25.035.0 kg/m2) of both the genders, aged 2570 years and recruited via

local newspapers, were included. Subjects with food intolerances or

allergies, weight loss 45 kg in the past 6 months or following a vegetarian

diet were excluded from participation. Other exclusion criteria were

diabetes mellitus with fasting blood glucose 4120 mg/dl or insulin

dependency, hypertension with multipharmacotherapy 42 drugs and

chronic gastrointestinal diseases. Volunteers underwent a brief medical

screening including a medical history questionnaire and blood test before

enrollment. We randomly assigned the subjects to either intervention

group (IG) or waiting-list control group (CG), stratied by age, BMI and

gender. Randomization was carried out using a randomization schedule

(generated using the random (RAND) function of Excel (Microsoft

Deutschland GmbH, Unterschleiheim, Germany)). Sequence of assignment was applied by a person who was not involved in recruiting and did

not have any contact with the participants before the assignment.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the Ethical Committee of the University

Medical Center Gttingen (27 March 2008). Volunteers were informed

about the nature of the study, and written consent was obtained before

the study participation.

Study design

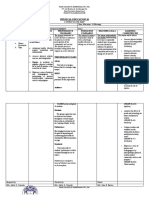

After randomization, the IG started the 12 weeks of intervention period.

Participants came to the study center weekly to receive the printed

instructions (6 weeks of detailed diet plans followed by 6 weeks of weight

maintenance instructions), whereas the CG did not receive any instructions

during that time period. After 12 weeks, outcome measurements (T1) for

both the groups were conducted. The IG did not receive any further

intervention for the following 40 weeks. Afterward, the 52-week outcome

measurements were made (T2a). The CG started 12 weeks of the same

intervention after the waiting period at T1. After intervention, the outcome

measurements (T1b) were made before starting their 40 weeks without

intervention followed by 52-week outcome measurements (T2b) (see

Figure 1).

Diet

Participants received weekly instructions during the rst 6 weeks of

intervention, these consisted of an informational letter, seven daily diet/

cooking plans, a shopping list and a supply manifest for that week. Every

daily diet plan included recipes for breakfast, lunch, dinner and two

portion-controlled sweet snacks with cooking instructions and exact food

quantities for all meals, providing an average of ~ 5440 kJ (1300 kcal)

per day. Nutrition data were calculated with the German software

DGE-pc professional 2.8 (Deutsche Gesellschaft fr Ernhrung e. V., Bonn,

Germany), based on the Bundeslebensmittelschlssel II.3 (German nutrient

database) and adapted to the recommendations for a weight loss diet of

1200 kcal given by the German Nutrition Society (data from DGE-pc

professional 2.8; Supplementary Data).

To achieve a fat modication comparable to Mediterranean diets,

walnuts, walnut oil, Alba oil (Swedish butter-avored canola oil) and

neutral canola oil, all naturally rich in -linolenic acid and oleic acid, were

primarily used as fat sources in the diet plans. All oils and walnuts used in

the diet plans were provided free of charge to the participants. Diet plans

also contained a high proportion of vegetables and fruits.

The plans included two portion-controlled sweet snacks, for example, a

small chocolate bar (25 g), one piece of low-fat fruit cake (150 g, for

example, apple on yeast dough) or one fruit yoghurt (150 g), to improve

palatability and sustainability and to prevent craving. Another focus was

~250 volunteers

T0 Screening

Blood tests, weight, blood pressure, height, waist circumference, questionnaires

Randomization for gender, age, BMI

n = 225

n = 101

Intervention group

n = 100

12 weeks of intervention

n = 124

Waiting list control group

n = 112

12 weeks without intervention

T1 (12 weeks)

Blood tests, weight, blood pressure, waist circumference, questionnaires

n = 72

40 weeks without intervention

n = 112

12 weeks of intervention

T1b (like T1)

n = 77

40 weeks without intervention

T2a /b (52 weeks)

Blood tests, weight, blood pressure, waist circumference, questionnaires

n = 109 (Intervention group = 56; Control group = 53)

Figure 1.

Flowchart of study design and study population.

European Journal of Clinical Nutrition (2015) 1 7

2015 Macmillan Publishers Limited

Weight loss with a modied Mediterranean-type diet

A Austel et al

3

on using recipes that were simple to prepare and time-saving both in the

purchase of goods and in cooking.

During the second 6 weeks of the intervention period, weekly

instructions included an informational letter and written instructions with

advice regarding weight maintenance strategies (that is, self-monitoring,

exible control of eating behavior, lower-fat food choices, 5 a day

recommendations for fruit and vegetables and physical activity in

everyday life).

Measurements

Body height was measured with a calibrated stadiometer without shoes at

the baseline. Body weight was measured on the calibrated scales with

subjects wearing light clothing and waist circumference was measured

with subjects wearing only nonrestrictive underwear at baseline, T1, T1b

(only CG) and T2a/T2b. Body weight was additionally measured weekly

during the intervention on a voluntary basis.

Venous blood samples were drawn after an overnight fast. All the tests

were performed at the laboratory of the University Medical Center

Gttingen. Fasting blood glucose, total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, LDL

cholesterol, triglycerides and urea were measured at baseline, T1, T1b (only

CG) and T2a/T2b.

Dietary intake was measured via standardized 7-day food diaries at

baseline, T1, T1b (only CG) and T2a/T2b. Food diaries were assessed with

DGE-pc professional 2.8 (see above).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the participants in groups IG and

CGa

IG

CG

P-value

100

21/79

52.36 0.89

85.06 1.23

1.68 0.01

30.05 0.27

102.16 1.39

94.10 1.00

206.22 4.07

134.07 3.34

61.77 1.60

125.36 5.89

112

17/95

52.64 1.06

84.07 1.09

1.67 0.01

30.12 0.25

103.17 0.91

97.75 1.13

205.68 3.40

135.60 2.92

59.59 1.22

131.46 6.19

NS

NS

NS

NS

NS

0.05

NS

NS

NS

NS

Group

n

Gender M/F

Age in years

Weight in kg

Height in m

BMI in kg/m2

Waist circumference in cm

Plasma glucose in mg/dl

Total cholesterol in mg/dl

LDL-C in mg/dl

HDL-C in mg/dl

Triglycerides in mg/dl

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; CG, control group; F, female; IG,

intervention group; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C,

low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; M, male; NS, not signicant. aValues are

given as mean s.e.m.

Table 2.

To measure the changes in eating behavior, we implemented the

Fragebogen zum Essverhalten, the German version of the Three-Factor

Eating Questionnaire by Stunkard and Messick18 in an enhanced version

with scales for rigid and exible control of eating behavior as subscales of

cognitive restraint.19 The questionnaire was applied at baseline, T1 and T1b

(only CG). For compliance reasons we did not use it at T2a/T2b.

Statistical analysis

Analyses were conducted with IBM SPSS Statistics 20 (IBM Corporation,

Armonk, NY, USA). All P-values were two-sided; P 0.05 was considered

statistically signicant. Data are presented as means s.d.

Normal distribution of data was conrmed by performing a KolmogorovSmirnov test. Within-group comparisons were performed using the

paired t-test if data were distributed normally or Wilcoxon test if nonnormally. Differences between groups were tested with unpaired t-test or

MannWhitney U-test. Correlations were measured with Pearsons

coefcient or Spearmans rho. For 1-year results, pooled data of both IG

and CG were processed in per-protocol analysis, including participants

from both the groups who completed the study and T2a/T2b assessment.

BMI and body weight were additionally analyzed in an intention-to-treat

analysis in baseline observation carried forward mode, using baseline data

as end result for dropouts.

RESULTS

Although 101 participants had been randomly assigned to group

IG and 124 to group CG, a total of 13 participants had to be

excluded from evaluation because of noncompliance (unreported

nut allergy, alternative weight-loss program during waiting period

and missing T1 assessment) or withdrawal of participation

consent. The resulting groups for evaluation consisted of 100

(IG) and 112 (CG) participants. Despite having to exclude

participants from the evaluation after randomization, the groups

were well matched in terms of the baseline characteristics

(Table 1).

12-Week weight changes

Within 12 weeks of intervention mean change in body weight in

completers was 5.15 kg in IG compared with 0.37 kg in CG, BMI

went down by 1.82 kg/m2 and 0.14 kg/m2, respectively and waist

circumference was reduced by 4.7 cm vs 0.88 cm, all differences

between the groups being highly signicant. In the intention-totreat analysis (baseline observation carried forward mode) mean

weight loss in the intervention group was 3.71 kg, BMI went down

by 1.31 kg/m2 and waist circumference was reduced by 3.32 cm.

These changes were signicantly different from those in the CG as

well (Table 2).

Weight loss during the 12-week intervention programa

Weight T0 in kg

Weight T1 in kg

Weight T0 T1 in kg

BMI T0 in kg/m2

BMI T1 in kg/m2

BMI T0 T1 in kg/m2

Waist circumference T0 in cm

Waist circumference T1 in cm

Waist circumference T0 T1 in cm

WHtR T0 in cm

WHtR T1 in cm

WHtR T0 T1 in cm

IG PP analysis (n = 72)

IG ITT analysis (n = 100)

CG (n = 112)

84.17 1.51

79.02 1.37

5.15 0.42

29.87 0.31

28.06 0.30

1.82 0.13

101.5 1.78

103.17 1.26

4.70 1.50

0.61 0.01

0.58 0.01

0.03 0.01

85.06 1.23

81.35 1.19

3.71 0.38

30.05 0.28

28.74 0.29

1.31 0.13

102.16 1.39

98.81 1.10

3.32 1.09

0.61 0.01

0.59 0.01

0.02 0.01

84.07 1.09

83.70 1.12

0.37 0.18

30.12 0.25

29.98 0.26

0.14 0.06

96.54 0.91

102.29 0.85

0.88 0.42

0.62 0.01

0.61 0.01

0.01 0.00

P-value

NS

##

###

, ***

NS

###

, **

###

, ***

NS

###

, **

###

, ***

NS

###

, ***

###

, ***

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; CG, control group; IG, intervention group; ITT, intention-to-treat analysis (baseline observation carried forward); NS, not

signicant; PP, per protocol; WHtR, waist-to-height ratio. aValues are given as mean s.e.m. Signicant change between IG PP analysis and CG: #P 0.05;

##

P 0.01; ###P 0.001. Signicant change between IG ITT analysis and CG: *P 0.05; **P 0.01; ***P 0.001.

2015 Macmillan Publishers Limited

European Journal of Clinical Nutrition (2015) 1 7

Weight loss with a modied Mediterranean-type diet

A Austel et al

4

Plasma lipids and glucose

Mean fasting triglycerides (IG 123.92 vs CG 130.52 mg/dl), total

cholesterol (206.25 vs 206.31 mg/dl), LDL cholesterol (133.12 vs

135.85 mg/dl) and HDL cholesterol (62.78 vs 60.00 mg/dl) did not

differ signicantly between the groups at T0. At T1, the

triglycerides were signicantly lower in IG with 108.86 mg/dl than

in CG with 143.09 mg/dl (P 0.001), as were total cholesterol with

193.69 vs 207.20 mg/dl and LDL cholesterol 125 vs 137.11 mg/dl

(all P 0.05). Differences in changes between the groups and

signicances in in-group changes are shown in Figure 2.

and hunger were reduced by 1.88 and 1.91 points, respectively.

The resulting differences between the groups at T1 were

signicant in all the scales (Figure 3).

A small but highly signicant negative correlation of 0.31

(P = 0.010; Spearman rho; IG completers) was found between the

baselineT1 change in exible cognitive restraint and weight

change at T1 (greater increase in exible cognitive restraint =

higher weight loss at T1).

One-year results

For the 1-year results we pooled the data of both the groups, with

week 0 as T0 for IG and T1 for CG, week 12 as T1 for IG and T1b for

CG, and week 52 as T2a and T2b, respectively.

The mean 12-week weight loss for 1-year completers was

6.07 kg. During the following 40 weeks without intervention, the

mean body weight went up 1.9 kg. Compared with the baseline,

the mean body weight at week 52 was still 4.17 kg lower.

Whereas changes in plasma glucose and total cholesterol

between week 0 and week 52 were not signicant,

Eating behavior (Fragebogen zum Essverhalten, enhanced

version)

Differences between the groups in the ve scales were not

signicant at the baseline. Although the changes between

baseline and T1 were minimal and not signicant for the CG,

the changes for IG were signicant in all the ve scales (P = 0.000).

Cognitive restraint went up by 4.16 points, rigid cognitive restraint

by 1.01 and exible cognitive restraint by 3.56. Disinhibation

p 0.01

15.00

12.54**

10.00

n.s.

p 0.001

p 0.001

0.81

1.14

n.s.

5.00

0.17

0.02

0.00

-0.90

-1.85*

-5.00

-7.18*

-10.00

-14.76**

-12.62***

-15.00

Glucose

Total cholesterol

LDL cholesterol

Intervention group

HDL cholesterol

Triglycerides

Control group

Figure 2. Mean changes (mg/dl) in plasma lipids and glucose (mg/dl) between baseline and 12-week measurements at T1. Signicant in-group

change between T0 and T1: *P 0.05; **P 0.01; ***P 0.001.

5

4.16

4

3.56

3

2

p 0.001

1.01

1

0.32

p 0.01

0.18

0.10

0

-1

p 0.001

p 0.01

-0.31

p 0.001

-0.67

-2

-1.88

-1.91

-3

CR

Rigid CR

Flexible CR

Intervention group

Figure 3.

Disinhibition

Hunger

Control group

Mean changes in eating behavior scales between baseline and 12-week measurements at T1. CR, cognitive restraint.

European Journal of Clinical Nutrition (2015) 1 7

2015 Macmillan Publishers Limited

Weight loss with a modied Mediterranean-type diet

A Austel et al

5

Table 3.

Per-protocol and intention-to-treat (baseline observation carried forward) analysis of both IG and CG over 1 year

Week 0

Week 12

Week 52

PP analysis

n

Weight in kg

BMI in kg/m2

Waist circumference in cm

WHtR in cm

Plasma glucose in mg/dl

Total cholesterol in mg/dl

LDL-C in mg/dl

HDL-C in mg/dl

Triglycerides in mg/dl

109

85.09 12.93

30.12 2.80

102.13 13.09

0.61 0.07

95.61 9.55

210.34 38.26

138.60 31.38

60.18 14.80

142.95 71.75

109

79.02 11.39

28.02 2.60

96.16 9.25

0.57 0.05

92.65 9.64

200.26 39.68

129.58 33.63

57.44 13.56

113.14 46.17

109

80.92 11.93

29.34 2.76

98.05 8.84

0.59 0.05

94.41 11.08

213.05 41.82

134.37 30.36

62.03 15.12

114.39 54.05

ITT analysis (BOCF)

n

Weight in kg

BMI in kg/m2

Waist circumference in cm

WHtR in cm

212

84.34 11.10

30.01 2.76

102.23 11.50

0.61 0.07

212

80.66 11.27

28.72 2.75

98.51 9.72

0.59 0.06

212

82.20 11.57

29.34 2.77

100.15 9.54

0.60 0.06

P-value

+++ ###

,

,

+++

,

+++

,

, ***

, ***

###

, ***

###

, ***

+++

,*

+++

, **

+++ #

,

+++ ##

, , ***

+++ ###

,

+++ ###

+++ ###

,

,

+++

,

+++

,

,

,

###

,

###

,

+++ ###

***

***

***

***

Abbreviations: BOCF, baseline observation carried forward; BMI, body mass index; CG, control group; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; IG,

intervention group; ITT, intention-to-treat; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; PP, per protocol; WHtR, waist-to-height ratio. Data are mean s.d.; week

0 = T0 for IG and T1 for CG; week 12 = T1 for IG and T1b for CG; week 52 = T2a and T2b, respectively. Signicant change between week 0 and week 12:

+

P 0.05; ++P 0.01; +++P 0.001. Signicant change between week 0 and week 52: #P 0.05; ##P 0.01; ###P 0.001. Signicant change between week 12 and

week 52: *P 0.05; **P 0.01; ***P 0.001.

LDL cholesterol (4.24 20.82 mg/dl; P 0.05) and triglycerides

(28.56 55.04 mg/dl; P 0.001) were signicantly lower and HDL

cholesterol (1.85 7.13; P 0.01) signicantly higher at week 52

than at week 0 (Table 3).

DISCUSSION

The present study shows that a two-phase self-help weight loss

concept over 12 weeks with a modied Mediterranean-type diet

using fat modication through canola oil, butter-avored canola

oil, walnuts and walnut oil, and two portion-controlled sweet daily

snacks induces clinically relevant weight loss in overweight and

grade 1 obese subjects both after 12 weeks and after 12 months.

The weight changes are accompanied with the favorable changes

in rigid and exible cognitive restraint.

Compliance

The two-phase self-help weight loss concept/program ended after

12 weeks. Compliance in this initial phase was 72% (69% for the

CG, starting the initial phase 3 months later). Even without any

professional therapeutical support between week 12 and 52, 51%

of all the participants (and 73% of those who completed the initial

phase) attended the follow-up at 52 weeks. For a self-help

concept, those rates are promising and may show a comparably

good sustainability of the behavior changes under free living

conditions. Probably compliance can be enhanced with parallel

professional support/counseling.

Walnuts and canola oil

A recently published study about nut consumption and lipid

prole by Askari et al.20 shows a signicant link between high nut

consumption and lower triglycerides, total cholesterol and

LDL cholesterol levels. In a meta-analysis of studies comparing

walnut-enriched diets with diverse control diets (for example,

fat-reduced, Mediterranean and cholesterol lowering), Banel and

Hu21 found in 2009 that walnut-enriched diets had higher

effects in lowering total and LDL cholesterol concentrations and

favored the decrease in triglycerides. In preventing cardiovascular

2015 Macmillan Publishers Limited

diseases in people with high cardiovascular risk, a walnut-enriched

energy-unrestricted Mediterranean diet reduced the relative risk

of major cardiovascular events by 30% compared with a low-fat

control diet.10 A review on the health benets of canola oil

showed that canola oil-based diets can reduce total cholesterol

and LDL cholesterol compared with a high-SFA diet.22 These

results suggest that the metabolic improvements we found in our

study are not solely due to the achieved weight loss but also the

result of substituting animal fat and hydrogenated vegetable fat

with walnuts, walnut oil and canola oil.

Sugar

The sucrose content (both natural occurring and added sucrose)

of the diet was 12.1% of total calories mainly from the two daily

portion-controlled sweet snacks. On average each snack contained 169 kcal and 12 g of sucrose. Sugar consumption in this

dosage corrupted neither weight loss nor improvements in

metabolic comorbidities of overweight and obese. The study

shows that sugar can be a part of a balanced diet even for weight

loss when used as portion-controlled sweet snacks. In the

CArbohydrate Ratio Management in European National diets

(CARMEN) trial, a low-fat, high-simple-carbohydrate and a low-fat,

high-complex-carbohydrate group were compared over 6

months.23 Both the groups achieved similar weight losses.

Numerous clinical studies have shown that sugar-containing

liquid meal replacements, when consumed in place of usual

meals, can lead to a signicant and sustained weight loss.2427 The

main carbohydrate source in liquid meal replacements is often

sugar, which is used to make high-protein meal replacements

more palatable. In the above-mentioned studies, 2533% of

energy was provided by sugar, thus exceeding the relative sucrose

content of this study by far. In a recent study by Bischoff et al.,27

ve sugar-containing high-protein meal replacements per day

were exclusively used as a low-calorie diet (820 kcal/d) for

12 weeks in obese subjects with a mean BMI of 42 kg/m2 as part

of a 52-week multidisciplinary outpatient weight management

program. One-year results were impressive (19.6/26.0 kg weight

loss per protocol (females/males) and 15.2/19.4 kg weight loss

intention-to-treat analysis last observation carried forward).

European Journal of Clinical Nutrition (2015) 1 7

Weight loss with a modied Mediterranean-type diet

A Austel et al

6

There is scientic evidence that sucrose in the diet is not per se a

problem. On one hand, sucrose can be an ingredient of diets with

a high potential for weight loss like low-calorie/very low-calorie

liquid meal replacements. On the other hand, sucrose can be an

ingredient of highly processed energy-dense ready-to-eat foods

and sugar-sweetened beverages that can contribute to the obesity

epidemic.28 The overall energy balance determines whether the

sugar becomes a cause or can be used as cure for obesity.

Metabolic changes

In a study by Dansinger et al.29 comparing several diets differing in

macronutrient composition, a signicant decrease in triglycerides

could be observed during the rst 2 months of intervention,

similar to the 12-week results of this study. Unlike in many other

weight loss studies, including Dansingers, triglycerides did not

increase during the intervention-free time after week 12 so that

triglycerides after 12 months were still signicantly lower than at

baseline. The observed increase in triglycerides in CG during the

waiting period is most likely due to the European Championship

soccer tournament during that time, for many people typically

accompanied by a high occurrence of social eating (barbecues,

sausages, potato chips, beer consumption and so on) and thus a

higher than usual consumption of fat and alcohol. Lowered total

cholesterol and LDL cholesterol can be observed in many other

weight loss studies too, as well as an unwanted initial decrease in

HDL cholesterol. These changes seem to be generally connected

with the weight loss under comparable diets with a fat content

between 25 and 30% of energy.2932 Studies by Rajaram et al.33 in

2009, Zambn et al.34 in 2000 and Iwamoto et al.35 in 2002,

investigating the effect of walnut consumption over a period of

46 weeks showed similar results on short-term reduction in total

cholesterol and LDL cholesterol. Usually, the observed changes in

blood lipid levels after weight loss interventions reverse in the

months following the intervention. Although the total cholesterol

at 12 months was not signicantly different from the baseline in

our study, LDL cholesterol still was signicantly lower. HDL

cholesterol levels reaching baseline level again is a common nd

in other weight loss studies;3032 however, in our study the levels

at 12 months were signicantly higher compared with the

baseline and that is not a common nding.

Differentiating weight loss and weight maintenance phases

Although the rigidity of weight loss diets with a diet plan makes it

relatively easy to follow the diet for a limited time and thus lose

weight, a rigid strategy is not suited for weight maintenance

because high rigid cognitive restraint (all-or-nothing/black and

white thinking) is associated with higher/more likely weight

regain.36 Under free living conditions, persons with high rigid

cognitive restraint will typically crave the forbidden foods and

binge sooner or later. Subsequently they consume large amounts

of calories in what can be described as counterregulation. As food

cravings occur more often under dieting and in 60% of

occurrences relate to the sweet foods,16 including a certain

amount of sweet foods to the diet may help to reduce the

cravings and thus increase the adherence to the diet plans. That

way people learn already during the restrictive diet plan phase

that such indulgence foods can be a part of a balanced diet and

are not forbidden.

A further disadvantage of rigid diet plans is that they do not

allow to train more favorable eating habits for long-term weight

stabilization. Thus, a high rigid cognitive restraint diet is less

suitable for weight maintenance than a diet with focus on exible

cognitive restraint.37 Teixeira et al.38 showed in a randomized

controlled weight management intervention that while total

restraint predicted short-term weight change, only change in

exible restraint predicted weight change after 24 months. Even

in persons with binge eating disorder, there was an increase in

European Journal of Clinical Nutrition (2015) 1 7

exible restraint under weight loss therapy associated with higher

weight loss plus improvement in binge eating.39

Despite 6 weeks of comparably rigid diet plans in this study, the

moderate increase in rigid cognitive restraint was considerably

lower than the profound increase in exible control. This suggests

that even a rigid weight loss diet with diet plans can lead to the

positive changes in cognitive restraint for weight maintenance if it

is followed by a phase of weight management training

concentrating on improving the exible cognitive restraint. That

way the advantages of diet plans can be combined with

increasing exible restraint necessary to enhance the chances

for weight maintenance.

CONCLUSIONS

A 12-week modied Mediterranean-type diet induced modest

weight loss in a sample of overweight and grade 1 obese subjects

without serious comorbidities. As we used a waiting-list control

design, it is unknown as to how effective the study diet is

compared with the other common diets for weight loss, such as a

traditional Mediterranean diet without adaptions or a lowcarbohydrate diet. This has to be addressed in future randomized

controlled trials with bigger sample sizes.

Although a 12-week self-help concept/program seems to be too

short for successful weight management from a professional

viewpoint, the study showed benets for the majority of

participants up to 52 weeks. This may be due to a relatively

sustainablebecause the diet was adapted to the local eating

habitsMediterranean-type diet and due to the inclusion of

weight stabilization strategies in the initial concept. Further

studies have to show whether success could be enhanced by

extending the initial concept to 26 or 52 weeks. In a clinical

environment, the success of a primary dietary intervention could

probably be further improved by combining the diet with an

intense physical activity program and with professional

counseling.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conict of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was funded by Taste of Sweden Deutschland (Oerlinghausen,

Germany), a manufacturer of avored canola oil, and by the California walnut

commission (Folsom, California, USA). Alba oil (avored canola oil) was donated by

Taste of Sweden, walnuts and walnut oil were donated by the California Walnut

Commission.

DISCLAIMER

None of the sponsors had any role in the trial design, data analysis or reporting of the

results.

REFERENCES

1 Max-Rubner-Institut, Editor. Nationale Verzehrsstudie II Ergebnisbericht,

Teil 1. 2008. Available at http://www.mri.bund.de/leadmin/Institute/EV/NVS_II_

Abschlussbericht_Teil_1_mit_Ergaenzungsbericht.pdf.

2 Mensink GBM, Schienkiewitz A, Haftenberger M, Lampert T, Ziese T,

Scheidt-Nave C. bergewicht und Adipositas in Deutschland. Ergebnisse der

Studie zur Gesundheit Erwachsener in Deutschland (DEGS1). Bundesgesundheitsblatt 2013; 56: 786794.

3 Ellrott T. bergewicht und Adipositas. Psychiatr Psychother Up2date 2008; 2:

405420.

4 Deutsche Adipositas-Gesellschaft. Evidenzbasierte Leitlinie Prvention und

Therapie der Adipositas Version 2014. Available at http://www.awmf.org/

leitlinien/detail/ll/050-001.html.

5 Australian Government National Health and Medical research Council

Department of Health and Ageing. Clinical practice guidelines for the

2015 Macmillan Publishers Limited

Weight loss with a modied Mediterranean-type diet

A Austel et al

7

6

7

8

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

management of overweight and obesity in adults, adolescents, and children in

Australia. 2013. Available at http://www.nhmrc.gov.au/guidelines/publications/n57.

Lau DCW, Douketis JD, Morrison KM, Hramiak IM, Sharma AM, Ur E et al. Canadian

clinical practice guidelines on the management and prevention of obesity in

adults and children (summary). CMAJ 2007; 176(Suppl 8): S1S13.

Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (Editor). Management of obesity:

a national clinical guideline. 2010.

Esposito K, Kastorini CM, Panagiotakos DB, Giugliano D. Mediterranean diet and

weight loss: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Metab Syndr Relat

Disord 2011; 9: 112.

Shai I, Schwarzfuchs D, Henkin Y, Shahar DR, Witkow S, Greenberg I et al. Weight

loss with a low-carbohydrate, Mediterranean, or low-fat diet. N Engl J Med 2008;

359: 229241.

Estruch R, Ros E, Salas-Salvad J, Covas MI, Corella D, Ars F et al. Primary

prevention of cardiovascular disease with a Mediterranean diet. N Engl J Med

2013; 368: 12791290.

Anderson JW, Konz EC, Frederich RC, Wood CL. Long-term weight-loss maintenance: a meta-analysis of US studies. Am J Clin Nutr 2001; 74: 579584.

Wing RR, Phelan S. Long-term weight loss maintenance. Am J Clin Nutr 2005; 82:

222 S225 S.

Max-Rubner-Institut, Editor. Nationale Verzehrsstudie II Ergebnisbericht,

Teil 2. 2008. Available at http://www.mri.bund.de/leadmin/Institute/EV/NVSII_

Abschlussbericht_Teil_2.pdf.

Mithril C, Dragstedt LO, Meyer C, Blauert E, Holt MC, Astrup A. Guidelines for the

New Nordic Diet. Public Helath Nutr 2012; 15: 19411947.

Mithril C, Dragstedt LO, Meyer C, Tetens I, Biltoft-Jensen A, Astrup A. Dietary

composition and nutrient content of the New Nordic Diet. Public Health Nutr 2013;

16: 775785.

Fletcher BC, Pine KJ, Woodbridge Z, Nash A. How visual images of chocolate affect

the craving and guilt of female dieters. Appetite 2007; 48: 211217.

Massey A, Hill AJ. Dieting and food craving. A descriptive, quasi-prospective study.

Appetite 2012; 58: 781785.

Stunkard AJ, Messick S. The three-factor eating questionnaire to measure dietary

restraint, disinhibition and hunger. J Psychosom Res 1985; 29: 7183.

Westenhfer J, Stunkard A, Pudel V. Validation of the exible and rigid control

dimensions of dietary restraint. Int J Eat Disord 1999; 26: 5364.

Askari G, Yazdekhasti N, Mohammadifard N, Sarrafzadegan N, Bahonar A, Badiei M

et al. The relationship between nut consumption and lipid prole among the

Iranian adult population; Isfahan Healthy Heart Program. Eur J Clin Nutr 2013; 67:

385389.

Banel DK, Hu FB. Effects of walnut consumption on blood lipids and other

cardiovascular risk factors: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Am J Clin Nutr

2009; 90: 5663.

Lin L, Allemekinders H, Dansby A, Campbell L, Durance-Tod S, Berger A et al.

Evidence of health benets of canola oil. Nutr Rev 2013; 71: 370385.

Saris WH, Astrup A, Prentice AM, Zunft HJ, Formiguera X, Verboeket-van de Venne WP

et al. The carbohydrate ratio management in European National diets. Int J Obes

Relat Metab Disord 2000; 24: 13101318.

24 Drewnowski A, Bellisle F. Liquid calories, sugar, and body weight. Am J Clin Nutr

2007; 85: 651661.

25 Heymseld SB1, van Mierlo CA, van der Knaap HC, Heo M, Frier HI.

Weight management using a meal replacement strategy: meta and pooling

analysis from six studies. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 2003; 27: 537549.

26 Wadden TA, West DS, Delahanty L, Jakicic J, Rejeski J et al. Look AHEAD Research

Group The Look AHEAD Study: a description of the lifestyle intervention and the

evidence supporting it. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2006; 14: 737752.

27 Bischoff SC, Damms-Machado A, Betz C, Herpertz S, Legenbauer T, Lw T et al.

Multicenter evaluation of an interdisciplinary 52-week weight loss program

for obesity with regard to body weight, comorbidities and quality of life a prospective study. Int J Obes (Lond) 2012; 36: 614624.

28 Monteiro CA, Moubarac JC, Cannon G, Ng SW, Popkin B, Dansinger ML et al. Ultraprocessed products are becoming dominant in the global food system. Obes Rev

2013; 14: 2128.

29 Dansinger ML, Gleason JA, Grifth JL, Selker HP, Schaefer EJ. Comparison of the

Atkins, Ornish, Weight Watchers, and Zone diets for weight loss and heart disease

risk reduction: a randomized trial. JAMA 2005; 293: 4353.

30 Goodpaster BH, Delany JP, Otto AD, Kuller L, Vockley J, South-Paul JE et al.

Effects of diet and physical activity interventions on weight loss and cardiometabolic risk factors in severely obese adults: a randomized trial. JAMA 2010; 304:

17951802.

31 Claessens M, van Baak MA, Monsheimer S, Saris WH. The effect of a low-fat, highprotein or high-carbohydrate ad libitum diet on weight loss maintenance and

metabolic risk factors. Int J Obes (Lond) 2009; 33: 296304.

32 Hnemann I, Ranke C, Austel A, Jarzemski S, Deeken I, Pleyer I et al. Changes of

cardiovascular risk factors while following one of three currently discussed

dietetic weight-reducing strategies. Aktuel Ernahrungsmed 2010; 35: 227235.

33 Rajaram S, Haddad EH, Mejia A, Sabat J. Walnuts and fatty sh inuence different

serum lipid fractions in normal to mildly hyperlipidemic individuals: a randomized

controlled study. Am J Clin Nutr 2009; 89: 16571663.

34 Zambn D, Sabat J, Muoz S, Campero B, Casals E, Merlos M et al. Substituting

walnuts for monounsaturated fat improves the serum lipid prole of hypercholesterolemic men and women. Ann Intern Med 2000; 132: 538546.

35 Iwamoto M, Imaizumi K, Sato M, Hirooka Y, Sakai K, Takeshita A et al. Serum lipid

proles in Japanese women and men during consumption of walnuts. Eur J Clin

Nutr 2002; 56: 629637.

36 Byrne S, Cooper Z, Fairburn C. Weight maintenance and relapse in obesity: a

qualitative study. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 2003; 27: 955962.

37 Westenhfer J, Engel D, Holst C, Lorenz J, Peacock M, Stubbs J et al. Cognitive and

weight-related correlates of exible and rigid restrained eating behavior. Eat

Behav 2013; 14: 6972.

38 Teixeira PJ, Silva MN, Coutinho SR, Palmeira AL, Mata J, Vieira PN et al. Mediators

of weight loss and weight loss maintenance in middle-aged women. Obesity

(Silver Spring) 2010; 18: 725735.

39 Blomquist KK, Grilo KM. Predictive signicance of changes in dietary restraint in

obese patients with binge eating disorder during treatment. Int J Eat Disord 2011;

44: 515523.

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on European Journal of Clinical Nutrition website (http://www.nature.com/ejcn)

2015 Macmillan Publishers Limited

European Journal of Clinical Nutrition (2015) 1 7

You might also like

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5783)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Active RecreationDocument5 pagesActive RecreationVhannie AcquiatanNo ratings yet

- EN Sample Paper 17 Unsolved MysteryDocument10 pagesEN Sample Paper 17 Unsolved MysteryShankhadeep ChoudhuryNo ratings yet

- Iron AllowancesDocument6 pagesIron AllowancesJenie Munar RosarioNo ratings yet

- 12 Physical Education Chapter 3Document24 pages12 Physical Education Chapter 3akanksha nayanNo ratings yet

- PWC Social Determinants of HealthDocument36 pagesPWC Social Determinants of HealthAnam FatimaNo ratings yet

- The Gabriel Method: The Revolutionary Diet-Free Way To Totally Transform Your Body - Jon GabrielDocument5 pagesThe Gabriel Method: The Revolutionary Diet-Free Way To Totally Transform Your Body - Jon Gabrielhukomeso0% (2)

- Microsoft Word - Stewart FAC 6-12-16 - WebsiteDocument32 pagesMicrosoft Word - Stewart FAC 6-12-16 - WebsiteEmanuele GiasiNo ratings yet

- Crisis ManagementDocument17 pagesCrisis ManagementAnonymous vNbLLN2iNo ratings yet

- Book StickerDocument4 pagesBook Stickerilanabiela90No ratings yet

- Philippine Festivals and Traditions MAPEH TestDocument19 pagesPhilippine Festivals and Traditions MAPEH TestGigi Reyes SisonNo ratings yet

- ESPGHAN Sugar Intake GuideDocument4 pagesESPGHAN Sugar Intake Guidedayanita1221No ratings yet

- Assessment and Management of Patients With ObesityDocument2 pagesAssessment and Management of Patients With ObesityaliNo ratings yet

- Performance of broiler chickens fed on Moringa oleifera leaf meal supplemented dietsDocument8 pagesPerformance of broiler chickens fed on Moringa oleifera leaf meal supplemented dietsMariz BallonNo ratings yet

- New Sip TemplateDocument84 pagesNew Sip TemplateOscar MatelaNo ratings yet

- Exercise Habit Among StudentsDocument30 pagesExercise Habit Among StudentsDaniel Hoe Wen ChuanNo ratings yet

- Healthy Lifestyle Changes to Combat ObesityDocument3 pagesHealthy Lifestyle Changes to Combat ObesityNorsyakira NawirNo ratings yet

- EBM Review Units1 4Document8 pagesEBM Review Units1 4Aissha ArifNo ratings yet

- Essential guide to anthropometry for child nutritionDocument2 pagesEssential guide to anthropometry for child nutritionChristian DaivaNo ratings yet

- Connected: The Six Rules of Social Networks and How They Shape Our LivesDocument5 pagesConnected: The Six Rules of Social Networks and How They Shape Our LivesJed Diamond100% (3)

- Curri Map Pe 10Document9 pagesCurri Map Pe 10Arnel BoholstNo ratings yet

- Eat Right... Transform Your Body-1Document34 pagesEat Right... Transform Your Body-1ozokwelu ebere100% (1)

- Research ProposalDocument36 pagesResearch ProposalShakilaNo ratings yet

- John W. Santrock - Life-Span Development-McGraw-Hill Education (2018) - 399-461-DikonversiDocument23 pagesJohn W. Santrock - Life-Span Development-McGraw-Hill Education (2018) - 399-461-DikonversiElsfrdlNo ratings yet

- 02 Nutrition and Nutritional DisordersDocument114 pages02 Nutrition and Nutritional DisordersMateen ShukriNo ratings yet

- Importance of PE for Weight Control, Stress Relief, Self-ConfidenceDocument6 pagesImportance of PE for Weight Control, Stress Relief, Self-ConfidenceJoe D'AmbrosioNo ratings yet

- BCP Evaluation FormDocument1 pageBCP Evaluation Formblackspyder1081No ratings yet

- National Food Strategy Recommendations in FullDocument73 pagesNational Food Strategy Recommendations in FullNeil ShellardNo ratings yet

- 10 Final Mapeh P.E. 10 Q2 M1 Week 5Document16 pages10 Final Mapeh P.E. 10 Q2 M1 Week 5Pedro GojoNo ratings yet

- Meigas: Nickname: Guajonas, Bruxas and Especially Xuxonas, Referring To His DarkDocument4 pagesMeigas: Nickname: Guajonas, Bruxas and Especially Xuxonas, Referring To His DarkJack RubyNo ratings yet

- Nutr 425 Diabetes AdimeDocument3 pagesNutr 425 Diabetes Adimeapi-341618058No ratings yet