Professional Documents

Culture Documents

USA Sentencing Recommendation For Jeremy Johnson

Uploaded by

Ben WinslowOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

USA Sentencing Recommendation For Jeremy Johnson

Uploaded by

Ben WinslowCopyright:

Available Formats

Case 2:11-cr-00501-DN-PMW Document 1461 Filed 04/22/16 Page 1 of 31

JOHN W. HUBER, United States Attorney (#7227)

ROBERT C. LUNNEN, Assistant United States Attorney (#4620)

JASON BURT, Assistant United States Attorney (#11200)

MICHAEL KENNEDY, Assistant United States Attorney (#8759)

KARIN M. FOJTIK, Assistant United States Attorney (#7527)

Attorneys for the United States of America

185 South State Street, Suite 300

Salt Lake City, Utah 84111

Telephone: (801) 524-5682

________________________________________________________________________

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

DISTRICT OF UTAH, CENTRAL DIVISION

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

2:11-CR-501 DN

Plaintiff,

SENTENCING MEMORANDUM

DISCUSSING RELEVANT

GUIDELINE APPLICATIONS

vs.

JEREMY JOHNSON and RYAN

RIDDLE,

Judge David O. Nuffer

Magistrate Paul M. Warner

Defendants.

The United States, through the undersigned Assistant United States Attorney, files

this memorandum pursuant to the Courts Notice of Briefing Schedule and Hearing dated

April 1, 2016 (Doc. 1430). The United States requests the Court consider this

memorandum and any additional information or evidence it may present prior to or at the

sentencing hearing; that the Court find defendant Johnsons sentencing guideline range is

324 - 405 months; and that defendant Riddles guideline range is 188 235 months. The

1

Case 2:11-cr-00501-DN-PMW Document 1461 Filed 04/22/16 Page 2 of 31

United States will make recommendations that the Court order a downward departure

from these guideline ranges. However, the United States requests that it be permitted to

reserve its final sentencing recommendation until after the completion of the PreSentence Report at the time of the sentencing hearing.

Background

On March 25, 2016, a jury found defendant Johnson guilty of Counts 2 through 9

of the Indictment and defendant Riddle guilty of Counts 2 through 7. (Doc. 1399).

Theses counts are violations of Title 18 United States Code, Section 1014, making false

statements to a bank. Each conviction of 1014 imposes a maximum penalty of up to 30

years imprisonment and a $1,000,000.00 fine. The Court has set the sentencing hearing

for the defendants on June 20, 2016. (Doc. 1402). A hearing to consider the applicable

guidelines is set for May 20. (Doc. 1430.) All of the counts of conviction are directly

based on merchant account applications defendants submitted by defendants to Wells

Fargo Bank through the ISO, Cardflex. Each application and others relevant applications

were submitted to Cardflex containing false and misleading information. Defendants did

so with the intention of and for the purpose of concealing from the bank iWorks true

ownership and control of the accounts.

In the Notice of Briefing Schedule dated April 1, 2016, the Court ordered the

parties brief the application and effect of the sentencing guidelines, including

enhancements and mitigations. (Doc. 1430). The Court specifically instructed the

parties to address United States Sentencing Guideline Sections 2B1.1- larceny (offenses

2

Case 2:11-cr-00501-DN-PMW Document 1461 Filed 04/22/16 Page 3 of 31

involving fraud); 3B1.1 Aggravating Role (leader and organizer); and 3C1.1Obstructing or Impeding the Administration of Justice. Id. The following memorandum

discusses these applications and other relevant sentencing guideline provisions to be

considered by the Court at the sentencing hearing and to impose a final disposition of

sentence.

Application of Relevant Sentencing Guidelines

Section 2B1.1

Section 2B1.1 of the United States Sentencing Guidelines applies to a variety of

federal crimes, including 18 U.S.C. 1014. Under U.S.S.G. 2B1.1 the base offense

level 7 applies, where the defendant is convicted of an offense that has a statutory

maximum term of imprisonment of 20 years or more. 18 U.S.C. 1014 has a statutory

maximum of 30 years, meeting the application requirements of Section 2B1.1(a) (1).

Therefore, Johnson and Riddles base offense level under this provision begins at a level

7.

Section 2B1.1 further increases the level of an offense beyond the base offense

level 7, depending on certain characteristics outlined in this guideline provision.

Subsection (b) of the guideline increases in the offense level based on graduating

amounts of monetary loss listed as (A) through (P), beginning at $5,000 or less (A),

adding 2 points to the base offense level, and ending with a loss of more than

$400,000,000 (P), adding 30 points to the base offense level. Calculating the amount of

loss to apply to this provision is within the discretion of the sentencing Court.

3

Case 2:11-cr-00501-DN-PMW Document 1461 Filed 04/22/16 Page 4 of 31

Calculating Loss Amounts

There are three legal questions that are at issue in calculating loss under 2B1.1 in

this case. First, who is a victim for purposes of calculating loss? Second, when, if ever,

is it appropriate to look at a defendants gain as a measure of loss under 2B1.1? And

third, is it proper to consider acquitted or other conduct occurring during the time the

crimes were committed?

As set forth next, the definition of victim goes well beyond just Wells Fargo Bank

and must include all the players affected by the defendants crimes. Second, if actual or

intended loss cannot reasonably be calculated, the Court is authorized to look at

defendants gain as a substitute for loss. And third, the Court may look to acquitted

conduct as relevant conduct so long as facts established the acquitted conduct beyond a

preponderance of the evidence, as with all other relevant conduct. Given these three legal

realities, the loss the Court should find here is great.

First, who are the victims of defendants conduct? The term victim is defined in

2B1.1, Application Note 1, as (A) any person who sustained any part of the actual

loss determined under subsection (b)(1); (Emphasis Added). The United States

asserts that it would be unreasonable and arbitrary to limit the scope of defendants

pecuniary harm and victims solely to Wells Fargo Bank. Doing so would be contrary to

the intent of the sentencing guidelines, that is, to measure the magnitude of the crime at

the time it was committed. United States v. Nichols, 229 F. 3d 975, 979 (10th Cir. 2000).

On the other hand, it is logical and fair for the Court to consider other victims as any

4

Case 2:11-cr-00501-DN-PMW Document 1461 Filed 04/22/16 Page 5 of 31

person who sustained any part of the loss, as suggested by 2B1.1, Application Note 1.

Defendants crimes in this case affected far more than just Well Fargo Bank.

During the trial, Martin Elliot, Ofer Yitzhaki and others testified that issuing banks

often have threshold amounts that they set to determine whether to incur the monetary

costs required to dispute the chargeback or to pay the chargeback amount out of their

own pocket. It is highly likely, considering the number of chargebacks caused by

defendants fraud and the common amounts of the iWorks recurring charges, ($29.95,

$39.95 and other lesser recurring charges) that many issuing banks chose to refund to

their customer/cardholder without seeking redress and reimbursement through the credit

card dispute system. Determining the amount of loss incurred by issuing banks who

reimbursed cardholders directly rather than dispute the chargeback through credit card

network would be difficult if not impossible. The United States would be required to

identify each cardholder who elected to charge back their iWorks purchase and then

identify the issuing bank of each of those cardholders. Each issuing bank would have to

provide records indicating the amount the either the direct payment made to their

cardholder or the amount obtained through the dispute system, less the cost incurred to

employ the dispute system. Determining the total amount of this foreseeable pecuniary

loss to the issuing banks is a monumental task and there is no reasonable method to

obtain this information. None the less, it cannot be reasonably disputed that losses

occurred to issuing banks of thousands of cardholders.

Case 2:11-cr-00501-DN-PMW Document 1461 Filed 04/22/16 Page 6 of 31

It is also reasonably foreseeable that defendants fraud would cause numerous

cards to be cancelled and reissued. Martin Elliot testified that as a result of the excessive

chargebacks caused by defendants, thousands of cards had to be reissued to cardholders,

thereby causing an additional cost and loss to the issuing banks from reissuing those

cards. To be fair, the United States acknowledges, and it was established at trial that a

portion of the fees assessed to Wells Fargo Bank, paid as a result of the excessive

chargebacks caused by iWorks, were filtered down by Visa to cover the some of the costs

incurred by the issuing banks. Determining whether those costs completely covered

losses incurred by the issuing banks is again difficult if not impossible and there is no

reasonable or timely method to obtain this information. The important point to

underscore is that defendants fraud and relevant conduct undoubtedly caused pecuniary

loss across the credit card and merchant banking system, and that Wells Fargo Bank was

not the only victim in this case monetarily affected by defendants criminal conduct.

Another example of pecuniary loss caused by defendants fraudulent conduct is

Cardflex. Andy Phillips, Will Swaim and Kelly Berg all testified regarding defendants

false statements, and that Riddle and Johnson represented to Cardflex that the numerous

owners listed on the merchant applications were legitimate third party business owners,

and that Johnson and iWorks were providing back end support or customer service to

these third party owners. Phillips testified that as a result of his belief and confidence in

Johnsons explanation, and his companys subsequent approval the nominee merchant

accounts, he was terminated by Wells Fargo Bank and lost a significant portion of his

6

Case 2:11-cr-00501-DN-PMW Document 1461 Filed 04/22/16 Page 7 of 31

business. He indicated that Wells Fargos termination of his business relationship with

the Bank, cost him millions of dollars in business revenue and a significant loss of

reputation in the payment processing industry. In addition, both Cardflex and Mach 1

(Blaze Processing) were sued by the Federal Trade Commission, directly as a result of

their business dealings with iWorks and their alleged negligence or failure to recognize

iWorks fraudulent applications and conduct during the underwriting process of approving

their merchant accounts.

Some of the nominee owners were victims of defendants fraud. Several

nominees testified that they did not sign any of the documents used by defendants to

obtain merchant accounts in their names and that their identities were used without their

knowledge or permission. Some of the nominee owners names were placed on the

match list as the result of iWorks and the defendants processing credit card sales and

incurring excessive chargeback in their names. Several banking and card network

witnesses testified at trial that once a persons name is placed on the match list, it is never

removed. It is unclear whether or not this will affect the nominees and their credit, or

whether it will affect any future decisions they may make to conduct their own business

and to obtain a merchant account. Although, any loss to these nominees is very

speculative at best, it is another example of how defendants self-serving interests took

priority above any potential damage their conduct and actions would cause to others.

The magnitude of defendants actions and fraudulent conduct has directly affected

numerous victims and has caused pecuniary loss. This loss was reasonably foreseeable or

7

Case 2:11-cr-00501-DN-PMW Document 1461 Filed 04/22/16 Page 8 of 31

they should have known would reasonably result from their actions. 1 Defendants

demonstrated a singular interest in obtaining monetary benefit without regard to any of

the negative consequences caused to the people and entities they used to perpetrate their

fraud. The United States plans to present witness testimony on May 20 of various parties

affected by the defendants crimes to provide the Court further evidentiary basis to

support finding that there was pecuniary harms to victims resulting from defendants

crimes.

Second, when if ever is it appropriate to looks at gain as a measure of loss under

2B1.1? Loss under 2B1.1(b)(1), may be determined by three different methods. The

general rule is that the loss amount used to calculate the enhancement shall be the greater

of the actual loss or the intended loss caused by the theft or fraud. 2 Where the court finds

there is no actual loss, the court may look to intended loss. Under circumstances where

the court finds that a loss did occur (actual or intended), but is unable to find a reasonable

method to calculate the actual or intended loss, the sentencing court may use gain as an

alternative method of determining the applicable loss amount. 3 If the court finds no

evidence of either actual or intended loss, the amount of defendants gain may not be

USSG 2B1.1 n. 3(A)(iv).

Cmt., n. 3(A).

USSG 2B1.1 Application Note 3(B).

8

Case 2:11-cr-00501-DN-PMW Document 1461 Filed 04/22/16 Page 9 of 31

used to calculate the amount of loss for purposes of the guideline calculations. Gain may

not act as an enhancement on its own. 4

Actual loss is defined as the reasonably foreseeable pecuniary harm that resulted

from the offense. 5 Pecuniary harm requires the harm be monetary, or that the harm is

otherwise readily measurable in money. 6 Reasonably foreseeable means the defendants

knew, or reasonably should have known that the loss was a potential result of their

conduct and the offense. 7 Court decisions emphasize that the sentencing court need only

make a reasonable estimation of loss; the sentencing court is not required to be exact and

should look to the scope and duration of the offense and revenues generated by similar

operations. 8 For example, similar operations in this case would include defendants use

of nominee owners to open other merchant accounts not charged in the indictment,

including banks other than Wells Fargo, during the same time frame and with similar

intent and purpose.

Intended loss is defined in 2B1.1 as the pecuniary harm that was intended to

result from the offense, and includes intended pecuniary harm that would have been

impossible or unlikely to occur. Id. 2B1.1, cmt., n.3(A) (ii). Intended loss can be used

as the method to determine the loss enhancement even if significantly greater than actual

4

Id.

USSG 2B1.1., cmt. n. 3(A)(i).

USSG 2B1.1 n. 3(A)(iii).

USSG 2B1.1 n. 3(A)(iv).

USSG 2B1.1 n. 3(C)(vi).

9

Case 2:11-cr-00501-DN-PMW Document 1461 Filed 04/22/16 Page 10 of 31

loss to measure the magnitude of the crime at the time it was committed. Nichols at

979.

The false statements made by Johnson and Riddle found the merchant account

applications caused Wells Fargo Bank to open and operate numerous merchant bank

accounts. But for defendants false statements, Wells Fargo would not have opened and

operated the accounts. Without access to the merchant banking system and credit card

network, defendants would he been unable to accept credit card payments, would not

have received any of the pecuniary gain; would not have caused the excessive volume

of chargebacks and the cancelation of thousands of credit cards; would not have caused

the significant disruption to the merchant banking system and credit card networks

described by the banking and network officials during the trial; and would not have

caused costs and loss to issuing banks and card holders.

By fraudulently obtaining access to merchant banking system, the defendants were

allowed to continue their credit card sales the names of nominee owners, knowing full

well that the same iWorks products would incur known and historically excessive

chargebacks. Defendants knew that their consistent chargebacks violated credit card

association rules and that the nominee merchant accounts would either be terminated by

Wells Fargo Bank, closed for excessive chargebacks or shut down by the defendants

themselves before the bank or card association actions were imposed, which is precisely

what the evidence at trial showed as defendants burned and churned through nominee

merchant accounts.

10

Case 2:11-cr-00501-DN-PMW Document 1461 Filed 04/22/16 Page 11 of 31

Although it was established at trial that the chargebacks and fines were protected

to some extend by reserve accounts established by Cardflex, and that Cardflex set aside a

percentage of iWorks credit card sales proceeds, the reserve accounts only guaranteed

Cardflex would have no loss from chargebacks, if and as long as those chargebacks did

not exceed the amount set aside in the reserve account. It was also established at trial that

had defendants chargebacks exceeded the reserve accounts, Wells Fargo Bank would

have been ultimately liable to iWorks consumers for repayment of the chargeback

amounts. Emails submitted into evidence and testimony demonstrated that iWorks knew

they would continue to have the same level of chargebacks using the nominee merchant

accounts as they did using prior accounts opened in iWorks and Johnson names.

Evidence established that as a result of this knowledge, Johnson and the defendants

purposely set up numerous merchant accounts for the purpose of having back up

accounts to move to when account were closed or terminated due to excessive

chargebacks. Emails admitted at trial indicate that the Johnson wanted back up

accounts set up not only through Cardflex at Wells Fargo Bank, but at other Banks as

well. Testimony and evidence further showed that the defendants followed this strategy

of moving credit card processing to new accounts when existing accounts were closed or

terminated by banks for excessive chargebacks. This intentional strategy was further

corroborated by the evidence introduced and testimony at trial showing that a number or

the nominee accounts were matched, closed or terminated. The majority of these

accounts were used to sell the same three iWorks products, Google, Grant, and a Fitness

11

Case 2:11-cr-00501-DN-PMW Document 1461 Filed 04/22/16 Page 12 of 31

program. The point is that defendants knew there would be excessive chargeback and

knew or should have known that pecuniary loss to others was a potential result of their

conduct and that the loss would not be limited to Cardflex or Wells Fargo Bank.

The problem faced here is that is it not reasonably possible to quantify the loss that

the victims incurred. Adequate banking records for all the issuing banks, consumers, etc.

do not likely exist. Nor is it possible to quantify when issuing banks ate the

chargebacks or contested them with Wells Fargo Bank. The costs to the credit card

system resulting from high chargebacks that numerous witnesses at trial testified to are

also not possible to quantify. Given these realities, it is appropriate in this case to look to

the defendants gain under 2B1.1.

Using Defendants Gain as an Alternative Measure of Loss

Due to the difficulty of determining the actual or intended loss that exists as a

result of the defendants fraud and that there is no reasonably determinable method of

calculating the actual or intended loss caused to the victims in this case, the Court is

entitled to use the alternative method estimating defendants gain as the amount of loss to

support the loss enhancement. U.S.S. G. 2B1.1, cmt. N. 3 (B), see United States v.

Washington, 634 F. 3d 1180 (10th Cir. 2011) and United States v. James, 592 F. 3d 1109

(10th Cir. 2010).

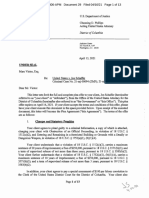

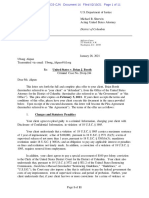

Exhibit 1 demonstrates the amount of gain obtained by the defendants solely

through the false merchant accounts for which they were convicted. If the court were to

12

Case 2:11-cr-00501-DN-PMW Document 1461 Filed 04/22/16 Page 13 of 31

restrict the loss to this amount only, 14 points should be added to increase the defendants

over all base office level related to loss from 7 to 21.

Exhibit 2 provides a list of four nominee merchant accounts used by defendants

for the purpose of processing credit card sales of iWorks and Johnsons products. The

use of other nominee owners to process credit card transactions and sell iWorks products

through other banks is the kind of similar conduct or operations that the Court should

consider when evaluating relevant conduct and intended loss and is appropriately

recommended by 2B1.1 n. 3(C)(vi).

The first line of Exhibit 2 shows credit card sales made by iWorks through

Diamond J. Media, a company incorporated in the name of Ryan Riddle. Evidence

presented at trial showed that there were no physical offices for Diamond J. Media; that

Ryan Riddle did not operate a separate entity under that name; that he did not control or

collect any of the revenue from Diamond J. Media and that all of the products sold to

Diamond J. Media where iWorks products. Many of the actions taken to disguise the true

nature of the nominee corporations and the 281 merchant accounts set up in their names

are similar to how Diamond J. Media was set up and utilized by iWorks. Witness Kelly

Berg (Cardflex) testified that she wrote Johnsons name on the Diamond J. Media

merchant application after she learned that it was associated or related to iWorks

business operation. This is not inconsistent with what all the Cardflex witnesses were

told about the character of the nominee owners and their relationship to iWorks and

Johnson. Riddle was listed on the application as a 100% owner of Diamond J. Media.

13

Case 2:11-cr-00501-DN-PMW Document 1461 Filed 04/22/16 Page 14 of 31

The amount of $9,654,181.40 dollars of iWorks credit card sales through a Harris Bank

merchant account open in the name of Ryan Riddle as 100% owner. Yet, all of the funds

processed were from iWorks sales and were for the sole benefit of iWorks and Johnson.

The second line of Exhibit 2 lists the merchant account established in the name of

Scott Leavitt as a nominee owner for iWorks. Leavitt testified that owned Employee Plus

and that business of this company was to lease employees to iWorks. Leavitt omitted any

mention during his direct examination that Employee Plus had other business operations.

Yet on cross-examination he admitted that Employee Plus opened a merchant account

and processed over 30 million dollars of credit card sales, all for the benefit of iWorks.

All of this money was gain solely attributable to the sales of iWorks products. Leavitt

stated that he charged Johnson a 2% fee to use the Employee plus name to process

iWorks credit card sales and he knew little if anything about the products being sold by

iWorks through the merchant account.

The third line lists the company Xcel Processing. Xcel processing was formed in

the name of Andy Johnson, defendants brother and later changed its ownership to Loyd

Johnston. Johnston testified that he did not operate or control any of the sales from the

shell companies formed in his name and that all of the products sold through nominee

corporations and merchants accounts in his name were controlled by and for the sole

benefit of iWorks. It is unknown at this time what if any testimony Andy Johnson

offered regarding his involvement in Xcel Processing. Trial transcripts may show

14

Case 2:11-cr-00501-DN-PMW Document 1461 Filed 04/22/16 Page 15 of 31

relevant testimony on this issue or the United States may call Andy Johnson to testify at

the sentencing hearing.

The fourth line of the chart lists the name of Funding Search Success. Margaret

Lacy Holm testified that she had no knowledge of the business transactions and sales of

Funding Search Success and was not aware of the amounts processed through a merchant

account bearing her name. $5,650,069.39 was processed in her name through this

merchant account. She testified she was shocked to learn about defendants use of her

name, the amount of money processed and reported in tax returns.

The fifth line in the chart merely repeats the amount of money processed through

the merchant accounts that were presented at trial, totaling a gain of $9,307,912.70.

(Trial Exhibit #934) If the Court were to restrict its calculation of loss to the defendants

direct gain through these nominee merchant accounts, 20 additional points would be

added as the loss enhancement, and would raise defendant Johnsons level from 7 to 27.

This amount is included on the list of Exhibit 2 to assist the Court in understanding the

total amount of gain received by iWorks and the defendants in relation to their criminal

conduct charge in the indictment and like or similar operations as contemplated by the

provisions of sentencing guideline 2B1.1. Exhibit 2 shows a total of $58,468,991.30

having been processed by iWorks through nominee owners and merchant accounts that

were presented at trial and/or accounts that defendants used to process credit card sales

under similar or identical circumstances. Using this amount as the gain attributable to

loss the base offense level of 7 would be increased by 24 points for a total of 31.

15

Case 2:11-cr-00501-DN-PMW Document 1461 Filed 04/22/16 Page 16 of 31

These calculations do not include other enhancements discussed below, including

use of sophisticated means (2 points), receiving gross receipts of an amount greater than

$1,000,000.00 (2 points), Leader/Organizer (4 points) and Obstruction or Impeding the

Administration of Justice (2 point). A finding by the Court that all of these enhancements

apply would increase the base offense level form Johnson from 31 to 41. The United

States requests the court consider the following discussion in reaching its decision

whether to apply other enhancements enumerated above.

Relevant Conduct

The third legal question relevant to the loss calculation is whether the Court can

consider acquitted conduct as part of its relevant conduct analysis. The answer is yes.

Well-established Supreme Court and Tenth Circuit law allows the sentencing court to

consider acquitted conduct in determining relevant conduct. 9 The sentencing court may

look to the entire endeavor or enterprise undertaken by a defendant in concert with

others, and relevant conduct under the Sentencing Guidelines includes much more than

the offense of conviction and may include uncharged or even acquitted conduct. 10 Just

last year, the Tenth Circuit reaffirmed this principal:

In calculating loss under the Guidelines, the district court does not limit itself to

conduct underlying the offense of conviction, but rather may consider all of the

defendants relevant conduct. United States v. Griffith, 584 F.3d 1004, 1011

(10th Cir. 2009) (quoting U.S.S.G. 1B1.3). The Guidelines define relevant

9

See United States v. Watts, 519 U.S. 148, 156 (1997); United States v. Alisuretove, 788 F.3d

1247, 1254-44 (10th Cir. 2015).

10

Id. at 1012 (internal citations omitted).

16

Case 2:11-cr-00501-DN-PMW Document 1461 Filed 04/22/16 Page 17 of 31

conduct broadly to include, in the case of jointly undertaken criminal activity (a

criminal plan, scheme, endeavor, or enterprise undertaken by the defendant in

concert with others, whether or not charged in a conspiracy, all reasonably

foreseeable acts and omission of others in furtherance of the jointly undertaken

criminal activity. U.S.S.G. 1B1.3(a)(1)(B). Thus relevant conduct under the

Guidelines . . . comprises more, often much more, than the offense of conviction

itself, and may include uncharged and even acquitted conduct. Griffith, 584 F.3d

at 1012. 11

(Emphasis Added).

If the United States establishes by a preponderance of the evidence relevant

criminal conduct under the guidelines, the court is free to consider that conduct, including

acquitted conduct, in determining the appropriate guideline sentence.

As the Court explained in an analogous Sixth Circuit case, United States v.

Warshak, 12 the district court will be required to make specific findings as to any loss or

gain amounts at the time of sentencing, and the court may look to intended loss when

determining the appropriate loss amount at the time of sentencing. 13

In Warshak, the Sixth Circuit determined that the district court erred because it

merely determined the loss amount as the defendants net sales without further

explanation. 14 Here, the United States directs the Court to United States Trial Exhibit

#934 and Exhibit 2 attached to this memorandum as the initial consideration from which

the Court may determination loss. Exhibit #934 summarized the bank records admitted

11

Alisuretove, 788 F.3d at 1254-55.

12

631 F.3d 266, 328-30 (6th Cir. 2011).

13

See United States v. Warshak 631 F.3d 266, 328-30 (6th Cir. 2011),

14

631 F.3d at 329-330.

17

Case 2:11-cr-00501-DN-PMW Document 1461 Filed 04/22/16 Page 18 of 31

into evidence, directly related to the 281 merchant account applications, all of which

contained the same false statements and fraudulent information contained in the merchant

accounts represented by Counts 2 through 9 of the Indictment. Again, but for the

fraudulent obtained merchant accounts, no credit card processing would have occurred,

and no revenue would have been deposited into iWorks bank accounts and then used for

direct benefit of Mr. Johnson and indirect benefit of Mr. Riddle.

Testimony at trial established during the 2007-08 time frame and as shown in

Exhibit 2 of this memorandum, iWorks processed much more than the $9 million dollars

in revenue. Because the $9 million received, deposited and used by defendants is directly

related to the defendants actions and intent to submit false and fraudulent merchant

account applications, this amount may appropriately represent the intended amount of

loss if the court restricts its consideration of loss only to the 281 merchant applications

admitted into evidence during the trial.

However, the United States asserts the amount of gain that should be used to

calculate defendants overall conduct, that more accurately demonstrates the magnitude

and measure of the defendants criminal behavior is the total amount of monetary gain

found in Exhibit 2, that is, $58,468,991.30.

Other Circuit Courts have upheld that an extension of credit from a bank or loan

proceeds from a scheme to defraud as appropriate measurements of loss under 2B1.1. In

United States v. Jenkins-Watts, the Eighth Circuit upheld the imposition of a loss

enhancement, where the defendant had lead a profitable credit card scheme that involved,

18

Case 2:11-cr-00501-DN-PMW Document 1461 Filed 04/22/16 Page 19 of 31

among other things, creating false drivers licenses to obtain fraudulent mortgages. 15 The

court upheld the determination of loss to include the proceeds from the loan scheme,

because the use of the false identification information was a part of the fraudulent loan

scheme. 16 Here, both Johnson and Riddle coordinated and helped direct the creation of

the straw businesses, addresses, phone numbers and nominee owners to create the illusion

that iWorks and Johnson, were not the applicants for the merchant bank accounts. The

nominee merchant accounts opened and operated by Wells Fargo Bank and other banks

allowed iWorks, Johnson and Riddle to continue to process credit card sales, providing

millions of dollars in revenue used for their exclusive benefit and control. These funds

are therefore reasonable and appropriate measurement of loss or gain under 2B1.1. 17

Testimony at trial supports the conclusion that Mr. Johnson intended to test the

chargeback limits of the merchant accounts he obtained, and accordingly he had the

necessary intent to cause the loss (or gain), at issue in this case. 18

The Court may also use the gain that resulted from the offense as an alternative

measure of loss only if there is a loss but it reasonably cannot be determined. 19 For

15

574 F.3d 950, 961 (8th Cir. 2009).

16

Id.

17

See United States v. Jenkins-Watts, 574 F.3d 950 (8th Cir. 2009).

18

See United States v. Manatau, 647 F.3d 1048, 1053-55 (10th Cir. 2011)

19

USSG 2b1.1 n. 3(B).

19

Case 2:11-cr-00501-DN-PMW Document 1461 Filed 04/22/16 Page 20 of 31

example, the guidelines allow the Court to look to a defendants gain as a measure of the

defendants unlawful conduct at time of sentencing. 20

As stated above, the defendants victims included many more players than Wells

Fargo alone. And the losses incurred by these victims were substantial, including

Cardflex losing its entire Wells Fargo portfolio, chargeback expenses incurred by the

issuing and acquiring banks above and beyond reserve accounts, issuing banks eating

the chargebacks, consumers cancelling their credit cards when they were charged with

recurring, unknown fees, etc. Because it is not possible to calculate this loss, the Court

should look to defendants gain as the measurement of loss. In so doing, the Court may

consider acquitted conduct and that shows a gain of at least $9 million. Other relevant

conduct includes the amounts defendants gained from processing through other nominee

merchant accounts as outlined above.

As an alternative argument only, the United States offers the following discussion

for the Courts consideration in determining the appropriate guideline sentence in this

case. Even if the Court finds no loss in this case, which is should not, the lowest

possible base offense level under 2B1.1 is 24. The calculation without loss, if including

a finding of the other enhancement below would begin at a base level of 7 under 2B1.1

and then add 10 levels for enhancements discussed below, including use of sophisticated

means (2 points), receiving gross receipts of an amount greater than $1,000,000.00 (2

points), Leader/Organizer (4 points) and Obstruction or Impeding the Administration of

20

USSG 2B1.1 n.3(B).

20

Case 2:11-cr-00501-DN-PMW Document 1461 Filed 04/22/16 Page 21 of 31

Justice (2 point). This combination of enhancements would increase Johnsons guideline

calculation to 17. However, 2B1.1(b)(16)(D) provides that, If the resulting offense level

determined under subdivision (A) or (B) is less than level 24, increase to level 24.

Therefore, Johnsons guideline level even without calculating any loss, but applying the

other relevant enhancements would be 24 and a guideline range of 51 -63 months.

Sophisticated Means- USSG 2B1.1(b)(9)(C)

The commentary to 2B1.1(b)(9)(C) defines sophisticated means as especially

complex or especially intricate offense conduct pertaining to the execution or

concealment of an offense. 21 The Guidelines do not require that every step of the

defendants scheme to be particularly sophisticated, rather, the guidelines commentary

makes clear that the enhancement applies when the execution or concealment of the

scheme, viewed as a whole is especially complex or especially intricate. 22 Even if a

single step is not complicated, repetitive and coordinated conduct can amount to a

sophisticated scheme. 23 One of the examples of sophisticated means includes the use of

shell corporations in different jurisdictions. 2B1.1, cmt. 9 (B)

In United States v. Weiss, 24 the Tenth Circuit upheld the application of the twopoint enhancement in where the defendant had organized a scheme to obtain mortgage

21

USSG 2B1.1(b)(9)(C), cmt. n. 8(B).

22

Id.

23

United States v. Jenkins-Watts, 574 F.3d 950, 962 (9th Cir. 2009).

24

630 F.3d at 1263 (10th Cir. 2010).

21

Case 2:11-cr-00501-DN-PMW Document 1461 Filed 04/22/16 Page 22 of 31

loans for low-income housing. 25 The defendant had helped borrowers obtain subsidized

loans through the FHA, even though they were ineligible by providing lenders with false

information about the buyers. 26 Here, Mr. Johnson and Riddle planned for the merchant

account applications to mask the true ownership of the merchant accounts, and allowed

iWorks to continue processing its transactions, when it would have been ineligible to

conduct this processing due to its presence on the match list. By using fraudulent

entities, and false information to obtain merchant accounts, the defendants used a

sophisticated scheme that supports this two-point enhancement.

In United States v. Snow, the Tenth Circuit upheld the imposition of the

sophisticated means sentencing enhancement where the mortgage fraud scheme involved

over 40 different banks. 27 The Court looked to the lengths the defendant went to conceal

the scheme from the financial institution involved in upholding the enhancement. 28 The

defendant was able to deceive trained and experienced banking personnel into approving

a number of fraudulent loans by providing information sufficient to fool the professionals

reviewing the documentation. 29 Mr. Johnson and Mr. Riddle carefully insured the

merchant account applications contained just enough information to mask the true

identity of the account holder, iWorks. Because the defendants took careful steps to

25

Id. at 1267-68.

26

Id.

27

United States

28

Snow at 1164.

29

468 Fed.Appx. at 842-43.

v. Snow, 663 F.3d 1156 (10th Cir.2011).

22

Case 2:11-cr-00501-DN-PMW Document 1461 Filed 04/22/16 Page 23 of 31

create numerous corporations in different states, obtained separate phone numbers and

tax identification numbers to place on the applications, and listed a false number of

employees and a nominee owner as the bona fide applicant, the sophisticated means

enhancement should apply.

In United States v. Jackson, 30 the Second Circuit upheld the application of the

two-point enhancement for sophisticated means where the defendant used a scheme

where he obtained the personal information for individuals by making a number of calls

to obtain personal information of the victims to make purchases. 31 The court found that

the enhancement should apply because defendant had linked unelaborate steps in a

coordinated way to exploit the vulnerabilities of the banking system supported the

application of the enhancement. 32 Mr. Johnson and Mr. Riddle exploited the relationship

underwriting relationship of Cardflex to Wells Fargo and the delayed auditing conducted

by the Wells Fargo Bank in the submission of the 281 fraudulent merchant accounts.

While their use of UPS addresses, and disposable phones may not appear particularly

sophisticated, the coordinated manner in which they used these deceptions to hide iWorks

true activity, all support the application of the sophisticated means enhancement.

In United States v. Jenkins-Watts, the Eighth Circuit upheld the sophisticated

means enhancement where the defendant had used identity fraud to obtain credit cards to

30

346 F.3d 22, 25 (2d Cir. 2003); (cited in United States v. Weiss, 630 F.3d 1263 (10th Cir.

2010)).

31

346 F.3d 22 (2nd Cir. 2003).

32

Jackson 346 F.3d at 25.

23

Case 2:11-cr-00501-DN-PMW Document 1461 Filed 04/22/16 Page 24 of 31

use in false mortgage loan applications. 33 To submit the false applications Mr. Johnson

had to find a nominee owner, establish an out-of-state address, obtain an out-of-state

phone number, and submit the applications to the bank. The court found that the

defendants ability to exploit different vulnerabilities in different systems in a

coordinated manner, made what might be simple criminal conduct, sophisticated. 34

The defendants conduct, including the manipulations of the victims credit lines, and the

creation of billing addresses, as well as other conduct, the court found the defendants

conduct sophisticated, and noted that the guideline applied where the conduct was both

pertaining to the execution of the scheme, or the concealment of the scheme. 35 The

repetitive, coordinated conduct may establish the sophisticate nature of a scheme. The

defendant had taken number of steps to obtain fraudulent loans including checking the

nominee applicants credit scores, obtaining the nominees personal information, and then

at the defendants direction, a line of credit was obtained to further the scheme. 36

The enhancement for use of sophisticated means requires the Court find that

Johnson and Riddle used a complex or intricate method of committing the crime. To

submit the false applications Mr. Johnson had to find numerous nominee owners,

establish out-of-state addresses, obtain out-of-state phone numbers, and submit the

applications to the bank. This intricate method of establishing the necessary information

33

574 F. 3d 950, 962 (8th 2009).

34

346 F.3d at 24-25.

35

Id.

36

574 F.3d at 962.

24

Case 2:11-cr-00501-DN-PMW Document 1461 Filed 04/22/16 Page 25 of 31

to complete the applications supports this enhancement. And the Court has already found

at the detention hearing that it was a very large and sophisticated scheme. (Transcript,

57:12-13.)

Riddle

Mr. Riddle was the general manager, and supervised the merchant accounts

department. He was copied on many emails, and sent emails expressing his management

and control over these entities and his agreement with the overall plan to deceive Wells

Fargo Bank. Accordingly, this enhancement should apply to both Mr. Johnson and Mr.

Riddle.

Gross Receipts > $1 million

This application applies where over $1 million of the gross receipts of an offense

went directly to a defendant individually, rather than all participants. 37 Gross receipts

include all property, real or personal, tangible or intangible, which is obtained directly or

indirectly as a result of such offense. 38

Repeatedly at trial, the court heard testimony that Mr. Johnson was the sole owner

of iWorks, the $9 million in proceeds described in Exhibit 934 and other relevant conduct

demonstrating the same use of nominees to process millions of dollars, support

37

USSG 2B1.1, n. 12 (A) & (B).

38

USSG 2B1.1 n. 11, (A) & (B).

25

Case 2:11-cr-00501-DN-PMW Document 1461 Filed 04/22/16 Page 26 of 31

application of this enhancement. Notably the enhancement applies when the defendant

has received over this amount either directly or indirectly as a result of the offense. 39

USSG 3B1.1(a) - Leader/Organizer

If the defendant was the organizer or leader of criminal activity that involved five

or more participants or was otherwise extensive, the defendants guideline calculations

should be increased by four points. 40 In determining whether an organization is

otherwise extensive, all persons involved during the entire offense are to be

considered. 41 A fraud that may have involved only a few knowing participants, but used

the unknowing services of many outsiders may be considered extensive. 42 Factors the

Court should consider in determining the role of leader or organizer include the exercise

of decision-making authority, the nature of participation in the commission of the

offense, the recruitment of accomplices, the claimed right to a larger share of the fruits of

the crime, the degree of participation in planning or organizing the offense, the nature and

scope of the illegal activity, and the degree of control and authority exercised over

others. 43 There can also be more than one person who qualifies as a leader or organizer

39

Id.; see also United States v. Weidner, 209 Fed.Appx. 826 (10th Cir. 2006)(unpublished).

40

USSG 3B1.1(a).

41

USSG 3B1.1 n. 3.

42

USSG 3B1.1 n. 3.

43

USSG 3B1.1 n. 4.

26

Case 2:11-cr-00501-DN-PMW Document 1461 Filed 04/22/16 Page 27 of 31

of a criminal association. 44 The adjustment exists because it is likely that persons who

exercise a supervisory or managerial role is the commission of the offense, tend to profit

more from it and present a greater danger to the public, and are more likely to

recidivate. 45 The burden remains on the United States to establish, by a preponderance

of the evidence, the facts necessary to establish the defendants leadership role. 46

The Tenth Circuit has held that the fact that a defendant recruited other

participants, directed their activities, paid them, exercised a leadership role over other

participants, and the enterprise involved more than five individuals supports the

imposition of the four-point enhancement for leader-organizer. 47

The testimony at trial indicated that Mr. Johnson directed Mr. Riddle, Mr. Payne,

and Mr. Loyd Johnston, and the merchant accounts department to submit the false

applications to Wells Fargo Bank. The false statements were made on merchant account

applications to insure iWorks, Mr. Johnsons company, could continue to accept credit

card payments. As the general manager of iWorks Riddle directly and indirectly

supervised all iWorks employees, including employees solicited to be nominee owners

for the fraudulent merchant accounts as well as the employees that worked in the

Merchant Account Department under Loyd Johnston, who created and/or organized the

creation of the 281 merchant account applications.

44

USSG 3B1.1 n. 4.

45

USSG 3B1.1 commentary.

46

United States v. Cruz-Camacho, 137 F.3d 1220 (10th Cir. 1998)

47

137 F.3d at 1224-25.

27

Case 2:11-cr-00501-DN-PMW Document 1461 Filed 04/22/16 Page 28 of 31

USSG 3C1.1 Obstruction of Justice

USSG 3C1.1, imposes a two-level enhancement where a defendant attempted to

obstruct or impede the administration of justice with respect to the investigation,

prosecution, or sentencing of the instant offense of conviction, and the obstructive

conduct must be related to the defendants offense of conviction, relevant conduct, or a

closely related offense. 48 The enhancement applies to a defendant who threatened,

intimidated, or unlawfully attempted to influence a witness or juror, directly or

indirectly. 49 There are numerous instances of obstruction that occurred during the trial.

1. Mr. Johnsons decision to contact Margaret Lacy Holm during her testimony at

trial, while she was represented by counsel, and his text messages to her in an effort to

influence her testimony is obstructive conduct. 50

2. A close friend of Mr. Johnsons attempted to influence two jurors during the

course of the trial. The United States contends this conduct would support this

enhancement. The United States may provide further testimony regarding this

obstruction at the time of sentencing.

3. Mr. Johnsons attempt to introduce fabricated evidence in the form of audio

recordings he made with a Wells Fargo employee unrelated to the facts and time period

in this case and during the course of the trial.

48

USSG 3C1.1.

49

USSG 3C1.1 n (4)(A).

50

See.e.g., United States v. Howard, 215 Fed. Appx. 750 (10th Cir. 2007) (unpublished).

28

Case 2:11-cr-00501-DN-PMW Document 1461 Filed 04/22/16 Page 29 of 31

4. Mr. Johnson attempted to manufacture evidence of merchant account

applications to Wells Fargo in the name of iWorks that were blatantly false and unrelated

to the applications charged in the indictment.

5. Mr. Johnsons unilateral excuse of Mr. Johnston from appearance at trial,

when he was scheduled by everyone to be here was obstructive during the trial.

(Detention Hearing Transcript, 57:23-25.)

6. Mr. Johnson caused unnamed parties to surreptitiously record meetings with

federal prosecutors during witness preparation sessions and selectively edited those

recordings in an effort to manufacture evidence and obstruct the proceedings.

Conclusion

The United States submits this memorandum and the following summary chart

representing the applicable sentencing enhancements that are supported by the

Sentencing Guideline provisions in this case.

Recommended Guideline levels applicable to Mr. Johnson:

2B1.1

Loss > $50 million (b)(1)(K)

24

Sophisticated Means (b)(10)

Gross Receipts > $1 million (b)(16)(A)

Leader or Organizer 3B1.1 (5 or more participants)

Obstruction or Impeding the Administration of Justice 3C1.1

29

Case 2:11-cr-00501-DN-PMW Document 1461 Filed 04/22/16 Page 30 of 31

Total Offense Level

41

Estimated Guideline Range

324-405 months

Recommended Guideline levels applicable to Mr. Riddle:

Under USSG 2B1.1, and the other relevant guidelines, the United States estimates that

Mr. Riddles guideline calculations should be:

Base Offense Level 2B1.1

Loss > $20 million (b)(1)(K)

22

Sophisticated Means (b)(10)

Gross Receipts > $1 million (b)(16)(A)

Leader or Organizer 3B1.1 (5 or more participants)

Total Offense Level:

36

Estimated Guideline Range :

188-235 months

Respectfully submitted this 22nd day of April, 2016.

JOHN W. HUBER

United States Attorney

/s/ R. Lunnen_____________

Robert C. Lunnen

Assistant United States Attorney

30

Case 2:11-cr-00501-DN-PMW Document 1461 Filed 04/22/16 Page 31 of 31

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I HEREBY CERTIFY that I am an employee of the United States Attorneys

Office, and that a copy of the foregoing SENTENCING MEMORANDUM

DISCUSSING RELEVANT GUIDELINE APPLICATIONS was caused to be served

on all persons named below, either by electronic filing notice, U.S. Mail (postage

prepaid), or hand delivery, on April 22, 2016.

Greg Skordas

Rebecca Skordas

Skordas Caston & Hyde

560 South 300 East, Suite 225

Salt Lake City, Utah 84111

rskordas@schhlaw.com

Attorney for Jeremy David Johnson

Steven B. Killpack

43 E 400 S

Salt Lake City, UT 84111

(801)656-5221

Email: killpack@rocketmail.com

Attorney for Ryan Riddle

Mary Corporon

Karra J. Porter

Sarah E. Spencer

Christensen and Jensen, P.C.

257 East 200 South, Suite 100

Salt Lake City, Utah 84111-2047

31

Case 2:11-cr-00501-DN-PMW Document 1461-1 Filed 04/22/16 Page 1 of 2

Case 2:11-cr-00501-DN-PMW Document 1461-1 Filed 04/22/16 Page 2 of 2

Case 2:11-cr-00501-DN-PMW Document 1461-2 Filed 04/22/16 Page 1 of 2

Case 2:11-cr-00501-DN-PMW Document 1461-2 Filed 04/22/16 Page 2 of 2

Case 2:11-cr-00501-DN-PMW Document 1461-3 Filed 04/22/16 Page 1 of 1

Net Deposits from Merchant Accounts to Depository Accounts

Depository Account

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

Alternate Media

Balance Processing

Big Bucks Pro

Blue Streak Processing

Bolt Marketing

Bottom Dollar

Bumble Marketing

Business Loan Success

Costnet Discounts

Cutting Edge Processing

Diamond J Media

eBusiness First

eBusiness Success

eCom Success

Excess Net Success

Fiscal Fidelity

Funding Search Success

Funding Success

GG Processing

GGL Rewards

Hooper Processing

Internet Fitness

Lifestyle for Fitness

Net Business Success

Net Commerce

Net Discounts

Net Fit Trends

Optimum Assistance

Premier Performance

Preview Marketing

Pro Internet Services

Razor Processing

Revive Marketing

Simcor Marketing

Smasher Marketing

Unlimited Processing

Zip Marketing

Bank Name

Depository Account

Number

SunFirst Bank

121016695

SunFirst Bank

121016737

Town and Country Bank 6002919

SunFirst Bank

121015309

SunFirst Bank

121015960

Zions Bank

34168187

Town and Country Bank 6002968

AmericanWest Bank

7600600131

Zions Bank

34166785

Zions Bank

34166793

The Village Bank

11024544

Zions Bank

34166751

The Village Bank

11025244

Town and Country Bank 6003123

Zions Bank

34167312

Zions Bank

34166744

The Village Bank

11025194

AmericanWest Bank

7600600125

Town and Country Bank 6002943

AmericanWest Bank

7600600135

Town and Country Bank 6002976

AmericanWest Bank

7600600129

AmericanWest Bank

7600600126

Zions Bank

34167320

The Village Bank

11025459

AmericanWest Bank

7600600132

Zions Bank

34166827

Town and Country Bank 6003057

The Village Bank

11025145

SunFirst Bank

121016703

The Village Bank

11025251

Town and Country Bank 6002620

Town and Country Bank 6002893

Town and Country Bank 6002901

SunFirst Bank

121016760

The Village Bank

11025467

SunFirst Bank

121016687

Total Net Deposits from Merchant Accounts

Deposits

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

61.04

0.00

0.00

51,738.07

44,373.41

83.15

567.63

306,723.19

0.00

8,652.23

4,873.35

1,022,299.82

94,977.62

1,246,503.72

0.00

324,443.38

227,576.38

974,257.31

0.00

664,606.62

104,151.27

268,525.25

800,763.17

2,871,800.71

1,957.38

103,389.92

92,466.09

0.00

329,105.80

0.00

0.00

1,420,291.38

0.00

0.00

0.00

1,630,337.74

0.00

12,594,525.63

Returns

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

(61.04)

0.00

0.00

(7,518.86)

(19,362.87)

(81.11)

(567.63)

(205,995.03)

0.00

(2,655.54)

(4,873.35)

(318,487.97)

(32,720.51)

(210,940.75)

0.00

(149,409.93)

(227,576.38)

(339,984.96)

0.00

(278,022.24)

(17,201.52)

(97,064.54)

(332,712.63)

(336,811.61)

(786.95)

(49,785.01)

(18,771.29)

0.00

(50,947.96)

0.00

0.00

(420,499.18)

0.00

0.00

0.00

(163,774.07)

0.00

(3,286,612.93)

Net Deposits

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

0.00

0.00

0.00

44,219.21

25,010.54

2.04

0.00

100,728.16

0.00

5,996.69

0.00

703,811.85

62,257.11

1,035,562.97

0.00

175,033.45

0.00

634,272.35

0.00

386,584.38

86,949.75

171,460.71

468,050.54

2,534,989.10

1,170.43

53,604.91

73,694.80

0.00

278,157.84

0.00

0.00

999,792.20

0.00

0.00

0.00

1,466,563.67

0.00

9,307,912.70

You might also like

- How to Get Rid of Your Unwanted Debt: A Litigation Attorney Representing Homeowners, Credit Card Holders & OthersFrom EverandHow to Get Rid of Your Unwanted Debt: A Litigation Attorney Representing Homeowners, Credit Card Holders & OthersRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- Equifax ComplaintDocument23 pagesEquifax ComplaintDaily Kos100% (1)

- ContractsDocument72 pagesContractsRodney Hampton100% (19)

- Class ComplaintDocument13 pagesClass ComplaintForeclosure Fraud100% (3)

- Lori Wigod v. Wells FargoDocument75 pagesLori Wigod v. Wells FargoForeclosure Fraud100% (1)

- California Supreme Court Petition: S173448 – Denied Without OpinionFrom EverandCalifornia Supreme Court Petition: S173448 – Denied Without OpinionRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Demolition Agenda: How Trump Tried to Dismantle American Government, and What Biden Needs to Do to Save ItFrom EverandDemolition Agenda: How Trump Tried to Dismantle American Government, and What Biden Needs to Do to Save ItNo ratings yet

- 19 Comprehending The Estate & Office 1Document104 pages19 Comprehending The Estate & Office 1Kevin Green100% (1)

- Motion to Dismiss OppositionDocument17 pagesMotion to Dismiss OppositionTaipan KinlockNo ratings yet

- Jenkins v. Equifax - ComplaintDocument35 pagesJenkins v. Equifax - ComplaintABC Action NewsNo ratings yet

- Doctrine of Separation of Powers in IndiaDocument19 pagesDoctrine of Separation of Powers in IndiaRupali RamtekeNo ratings yet

- October 2020 Nuke Bizzle EDD Fraud IndictmentDocument10 pagesOctober 2020 Nuke Bizzle EDD Fraud IndictmentJohn DodgeNo ratings yet

- Opinion Langley v. Statebridge Company LLCDocument6 pagesOpinion Langley v. Statebridge Company LLCAdam DeutschNo ratings yet

- Plea Agreement For Jan. 6 Defendant Robert LyonDocument12 pagesPlea Agreement For Jan. 6 Defendant Robert LyonDaily Kos100% (1)

- 001 LBP Vs Banal 434 Scra 543Document13 pages001 LBP Vs Banal 434 Scra 543Maria Jeminah Turaray0% (1)

- Boa Class ActionDocument44 pagesBoa Class ActionAnonymous BLkOv8hKNo ratings yet

- Chase Card FeesDocument27 pagesChase Card FeesAnonymous NKPsAVwNo ratings yet

- Frydman V EquifaxDocument5 pagesFrydman V EquifaxJayNo ratings yet

- METROPOLITAN vs. MARIÑASDocument2 pagesMETROPOLITAN vs. MARIÑASMarianne AndresNo ratings yet

- Foronda vs. GuerreroDocument10 pagesForonda vs. GuerreroAdrianne BenignoNo ratings yet

- Madeja Vs CaroDocument1 pageMadeja Vs Caroaniciamarquez2222No ratings yet

- Allied Banking Corporation v. CIR (Exception To Requisite of Filing An Admin Protest Before Appeal To CTA)Document11 pagesAllied Banking Corporation v. CIR (Exception To Requisite of Filing An Admin Protest Before Appeal To CTA)kjhenyo218502No ratings yet

- Law Reporting in IndiaDocument15 pagesLaw Reporting in IndiaSidharth B. PaiNo ratings yet

- Willex Vs CADocument3 pagesWillex Vs CALee Sung YoungNo ratings yet

- Pita Vs CADocument2 pagesPita Vs CAJezelle GoisNo ratings yet

- 11 - People V CeredonDocument2 pages11 - People V CeredonAndrea RioNo ratings yet

- Musk Tesla Trial Request To TransferDocument16 pagesMusk Tesla Trial Request To TransferGMG EditorialNo ratings yet

- United States v. Arthur Maurello, 76 F.3d 1304, 3rd Cir. (1996)Document21 pagesUnited States v. Arthur Maurello, 76 F.3d 1304, 3rd Cir. (1996)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Circuit JudgesDocument16 pagesCircuit JudgesScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States District Court Eastern District Kentucky Central Division Lexington Criminal Action No. 5:23-Cr-24-Kkc-Eba States AmericaDocument9 pagesUnited States District Court Eastern District Kentucky Central Division Lexington Criminal Action No. 5:23-Cr-24-Kkc-Eba States AmericaThe Lexington Times100% (1)

- NIXON Robert Govt Sentencing MemoDocument14 pagesNIXON Robert Govt Sentencing MemoHelen BennettNo ratings yet

- Bell PleaDocument13 pagesBell PleaJ RohrlichNo ratings yet

- 11712859602Document16 pages11712859602charlie minatoNo ratings yet

- District of Columbia: 1. Charges and Statutory PenaltiesDocument11 pagesDistrict of Columbia: 1. Charges and Statutory PenaltiesJ RohrlichNo ratings yet

- United States v. Howard, 10th Cir. (2015)Document11 pagesUnited States v. Howard, 10th Cir. (2015)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Schaffer Plea AgreementDocument13 pagesSchaffer Plea AgreementIndiana Public Media NewsNo ratings yet

- Kathy v. Kathy, Civil CourtDocument26 pagesKathy v. Kathy, Civil CourtXerxes WilsonNo ratings yet

- Plea Agreement As To Jon Ryan SchafferDocument13 pagesPlea Agreement As To Jon Ryan SchafferInvestor ProtectionNo ratings yet

- Polotan vs. CADocument5 pagesPolotan vs. CAKatrina Quinto PetilNo ratings yet

- Oath Keepers J6: Jason Dolan Plea AgreementDocument13 pagesOath Keepers J6: Jason Dolan Plea AgreementPatriots Soapbox InternalNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Tenth CircuitDocument8 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Not PrecedentialDocument14 pagesNot PrecedentialScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Raymond K MontoyaDocument23 pagesRaymond K MontoyaReporterJennaNo ratings yet

- 2Document16 pages2charlie minatoNo ratings yet

- Lillie B. Cowan, Counter-Defendant v. Miles Rich Chrysler-Plymouth, Counter-Claimant, 885 F.2d 801, 11th Cir. (1989)Document5 pagesLillie B. Cowan, Counter-Defendant v. Miles Rich Chrysler-Plymouth, Counter-Claimant, 885 F.2d 801, 11th Cir. (1989)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Courts Archive: WWW Nited Tates Ourts ORGDocument12 pagesUnited States Courts Archive: WWW Nited Tates Ourts ORGCrystal ScurrNo ratings yet

- United States v. Kenny Joe James, 993 F.2d 1540, 4th Cir. (1993)Document5 pagesUnited States v. Kenny Joe James, 993 F.2d 1540, 4th Cir. (1993)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Show Public DocDocument18 pagesShow Public DocBleak NarrativesNo ratings yet

- Not PrecedentialDocument21 pagesNot PrecedentialScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Show Temp - PLDocument9 pagesShow Temp - PLThe Lexington TimesNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals: Opinion On Rehearing UnpublishedDocument11 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals: Opinion On Rehearing UnpublishedScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Jeremy Grace Proud Boy Plea AgDocument11 pagesJeremy Grace Proud Boy Plea AgDaily KosNo ratings yet

- 2LOLES Gregory Govt Supp Sentencing MemoDocument403 pages2LOLES Gregory Govt Supp Sentencing MemoHelen BennettNo ratings yet

- Eugene Franklin v. First Money, Inc., D/B/A E-Z Finance Plan, United States of America, Intervenor-Appellee, 599 F.2d 615, 1st Cir. (1979)Document6 pagesEugene Franklin v. First Money, Inc., D/B/A E-Z Finance Plan, United States of America, Intervenor-Appellee, 599 F.2d 615, 1st Cir. (1979)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- PublishedDocument23 pagesPublishedScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Brunton, 10th Cir. (2007)Document10 pagesUnited States v. Brunton, 10th Cir. (2007)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Attorneys For Midland Loan Services, IncDocument13 pagesAttorneys For Midland Loan Services, IncChapter 11 DocketsNo ratings yet

- Not PrecedentialDocument7 pagesNot PrecedentialScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Larson V Money Control Inc Christopher Clarkson Riverside California FDCPA ComplaintDocument8 pagesLarson V Money Control Inc Christopher Clarkson Riverside California FDCPA ComplaintghostgripNo ratings yet

- HEARING DATE: June 7, 2011 HEARING TIME: 2:00 P.M.: Professional Fees ExpensesDocument8 pagesHEARING DATE: June 7, 2011 HEARING TIME: 2:00 P.M.: Professional Fees ExpensesChapter 11 DocketsNo ratings yet

- Brian Booth - Plea AgreementDocument11 pagesBrian Booth - Plea AgreementWashington ExaminerNo ratings yet

- Booth Plea BargainDocument11 pagesBooth Plea BargainJ RohrlichNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Fourth CircuitDocument10 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Fourth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- (ECF No. 27) Reply in Support of Plaintiff's Motion To Remand and For Costs and Expenses (00125225xA34F2)Document50 pages(ECF No. 27) Reply in Support of Plaintiff's Motion To Remand and For Costs and Expenses (00125225xA34F2)Cathy BrennanNo ratings yet

- Oath Keeper William Todd Wilson Plea AgreementDocument14 pagesOath Keeper William Todd Wilson Plea AgreementDaily KosNo ratings yet

- USA v. RaPower-3 Et Al Doc 35 Filed 25 Mar 16 PDFDocument10 pagesUSA v. RaPower-3 Et Al Doc 35 Filed 25 Mar 16 PDFscion.scionNo ratings yet

- Bauer IndictmentDocument6 pagesBauer IndictmentSpectrum MediaNo ratings yet

- Ivory Dorsey v. Citizens & Southern Financial Corporation, 678 F.2d 137, 11th Cir. (1982)Document4 pagesIvory Dorsey v. Citizens & Southern Financial Corporation, 678 F.2d 137, 11th Cir. (1982)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Filed: Patrick FisherDocument14 pagesFiled: Patrick FisherScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Teva Whistleblower (SEC Response)Document38 pagesTeva Whistleblower (SEC Response)Mike KoehlerNo ratings yet

- Plea Letter For Huttle, Matthew Filed 8/10/23Document11 pagesPlea Letter For Huttle, Matthew Filed 8/10/23Indiana Public Media NewsNo ratings yet

- U.S. v. Sun Myung Moon 532 F.Supp. 1360 (1982)From EverandU.S. v. Sun Myung Moon 532 F.Supp. 1360 (1982)No ratings yet

- Utah Attorney General/DABC Motion To ExcludeDocument10 pagesUtah Attorney General/DABC Motion To ExcludeBen WinslowNo ratings yet

- State v. MacNeillDocument37 pagesState v. MacNeillBen WinslowNo ratings yet

- NSA Wayne Murphy DeclarationDocument17 pagesNSA Wayne Murphy DeclarationBen WinslowNo ratings yet

- Deadpool Lawsuit Witness RulingDocument19 pagesDeadpool Lawsuit Witness RulingBen WinslowNo ratings yet

- Deadpool Lawsuit, Utah Attorney General's Motion For Summary JudgmentDocument32 pagesDeadpool Lawsuit, Utah Attorney General's Motion For Summary JudgmentBen WinslowNo ratings yet

- Equality Utah, NCLR Injunction RequestDocument68 pagesEquality Utah, NCLR Injunction RequestBen WinslowNo ratings yet

- Brewvies Motion To ExcludeDocument42 pagesBrewvies Motion To ExcludeBen WinslowNo ratings yet

- Mike's Smoke, Cigar & Gifts v. St. GeorgeDocument13 pagesMike's Smoke, Cigar & Gifts v. St. GeorgeBen WinslowNo ratings yet

- Geist Shooting RulingDocument7 pagesGeist Shooting RulingBen WinslowNo ratings yet

- Brown Cert ReplyDocument17 pagesBrown Cert ReplyBen WinslowNo ratings yet

- State v. Martinez-CastellanosDocument53 pagesState v. Martinez-CastellanosBen WinslowNo ratings yet

- ULCT AuditDocument16 pagesULCT AuditBen WinslowNo ratings yet

- Unified Fire Authority AuditDocument68 pagesUnified Fire Authority AuditBen WinslowNo ratings yet

- Unified Fire Service Area AuditDocument22 pagesUnified Fire Service Area AuditBen WinslowNo ratings yet

- Hildale, Colorado City FilingDocument26 pagesHildale, Colorado City FilingBen WinslowNo ratings yet

- Bistline v. Jeffs RulingDocument24 pagesBistline v. Jeffs RulingBen WinslowNo ratings yet

- NSA Lawsuit RulingDocument20 pagesNSA Lawsuit RulingBen WinslowNo ratings yet

- Feds Closing Brief in FLDS Discrimination CaseDocument198 pagesFeds Closing Brief in FLDS Discrimination CaseBen WinslowNo ratings yet

- Brown v. Buhman Opposition BriefDocument44 pagesBrown v. Buhman Opposition BriefBen WinslowNo ratings yet

- 10th Circuit Court Ruling On Contact Lens LawsuitDocument40 pages10th Circuit Court Ruling On Contact Lens LawsuitBen WinslowNo ratings yet

- VidAngel CEO DeclarationDocument8 pagesVidAngel CEO DeclarationBen WinslowNo ratings yet

- John Wayman Plea DealDocument7 pagesJohn Wayman Plea DealBen WinslowNo ratings yet

- VidAngel RulingDocument22 pagesVidAngel RulingBen WinslowNo ratings yet

- U.S. Attorney Response To DetentionDocument9 pagesU.S. Attorney Response To DetentionBen WinslowNo ratings yet

- Legislative Management Committee ReportDocument34 pagesLegislative Management Committee ReportBen WinslowNo ratings yet

- FLDS Labor OrderDocument22 pagesFLDS Labor OrderBen WinslowNo ratings yet

- VidAngel Injunction StayDocument24 pagesVidAngel Injunction StayBen WinslowNo ratings yet

- State Response Equality UtahDocument27 pagesState Response Equality UtahBen WinslowNo ratings yet

- Bennett v. BigelowDocument25 pagesBennett v. BigelowBen WinslowNo ratings yet

- DABC Liquor Store ReportDocument74 pagesDABC Liquor Store ReportBen Winslow100% (1)

- Not PrecedentialDocument4 pagesNot PrecedentialScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Script For Criminal Law ProjectDocument3 pagesScript For Criminal Law ProjectballehNo ratings yet

- Court Invalidates Substituted ServiceDocument6 pagesCourt Invalidates Substituted ServiceLalaine Manahan-UrbinoNo ratings yet

- 3D Insular Life v. Paz KhuDocument1 page3D Insular Life v. Paz KhuEric RamilNo ratings yet

- 2010-08 - Order Recalling Certain Writs of Bodily Attachment Over 5 Years OldDocument328 pages2010-08 - Order Recalling Certain Writs of Bodily Attachment Over 5 Years OldAnna MNo ratings yet

- Seminar FLW 2018march25 26Document7 pagesSeminar FLW 2018march25 26ichchhit srivastavaNo ratings yet

- OCA v. ReyesDocument16 pagesOCA v. ReyesJardine Precious MiroyNo ratings yet

- River Plate and Brazil Conferences v. Pressed Steel Car Company, Inc., Federal Maritime Board, Intervening, 227 F.2d 60, 2d Cir. (1955)Document6 pagesRiver Plate and Brazil Conferences v. Pressed Steel Car Company, Inc., Federal Maritime Board, Intervening, 227 F.2d 60, 2d Cir. (1955)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Alternative dispute resolution in the PhilippinesDocument5 pagesAlternative dispute resolution in the PhilippinesSittie Fatmah Hayamirah SinalNo ratings yet

- Court Rules Hearing Required to Resolve Indirect Contempt ChargeDocument10 pagesCourt Rules Hearing Required to Resolve Indirect Contempt ChargetabanginfilesNo ratings yet

- The Negotiable Instruments (Amendment) Bill, 2018Document2 pagesThe Negotiable Instruments (Amendment) Bill, 2018Jaskeerat Singh JoharNo ratings yet

- Uttarakhand President RuleDocument64 pagesUttarakhand President RuleFirstpostNo ratings yet

- Del Cid v. Valmont Industries - Document No. 4Document1 pageDel Cid v. Valmont Industries - Document No. 4Justia.comNo ratings yet

- Alcantara-Daus V de Leon PDFDocument10 pagesAlcantara-Daus V de Leon PDFPatrick CanamaNo ratings yet

- RolexDocument5 pagesRolexRe doNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Fourth CircuitDocument8 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Fourth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Philippines Supreme Court Ruling on Teacher's Probation ConditionDocument3 pagesPhilippines Supreme Court Ruling on Teacher's Probation ConditionRachel BayaniNo ratings yet

- Constitutional .Petition .127 of 2012Document221 pagesConstitutional .Petition .127 of 2012Khan1081No ratings yet