Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Moore v. United States, 429 U.S. 20 (1976)

Uploaded by

Scribd Government DocsCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Moore v. United States, 429 U.S. 20 (1976)

Uploaded by

Scribd Government DocsCopyright:

Available Formats

429 U.S.

20

97 S.Ct. 29

50 L.Ed.2d 25

John David MOORE, Jr.

v.

UNITED STATES.

No. 75-1692.

Oct. 18, 1976.

PER CURIAM.

John David Moore, Jr., was convicted in a bench trial of possession of heroin

with intent to distribute it, in violation of 21 U.S.C. 841(a)(1). In an

unpublished order, the Court of Appeals summarily affirmed the judgment of

conviction.

In early January 1975, police officers received a tip from an informant that

Moore and others were in possession of heroin at "Moore's apartment." The

police obtained a search warrant and entered the apartment, where they found

Moore lying face down near a coffee table in the living room. Also present in

the apartment was a woman who was sitting on a couch in the same room. Bags

containing heroin were found both on top of and beneath the coffee table, and

they were seized along with various narcotics paraphernalia.

(1) At a consolidated hearing on Moore's motion to suppress evidence and on

the merits, the prosecution adduced no admissible evidence showing that

Moore was in possession of the heroin in the apartment in which he and the

woman were found other than his proximity to the narcotics at the time the

warrant was executed. Indeed, one police officer testified that he did not find

"any indications of ownership of the apartment." In his closing argument on the

merits, however, the prosecutor placed substantial emphasis on the out-of-court

declaration of the unidentified informant:

"(A) confidential informant came to Detective Uribe and said, 'I have

information or I have through personal observation, know that John David

Moore resides at a certain apartment here in El Paso, Texas, and he is in

possession of a certain amount of heroin.' "

5

In adjudging Moore guilty, the trial court found that he had been in close

proximity to the seized heroin, that he was the tenant of the apartment in

question, and that he had, therefore, been in possession of the contraband. In

making these findings, the court expressly relied on the hearsay declaration of

the informant:

"Information revealed by the confidential informant and relied upon in the

preparation of the Affidavit disclosed that John David Moore was the occupant

of Apartment # 60, Building # 7, Hill Country Apartments, 213 Argonaut, El

Paso, Texas."

Defense counsel objected to the court's reliance upon hearsay evidence, but the

judge refused to amend this finding except to add the phrase "at the time of the

seizure" to the end of the sentence.

There can be no doubt that the informant's out-of-court declaration that the

apartment in question was "Moore's apartment," either as related in the search

warrant affidavit or as reiterated in live testimony by the police officers, was

hearsay and thus inadmissible in evidence on the issue of Moore's guilt.

Introduction of this testimony deprived Moore of the opportunity to crossexamine the informant as to exactly what he meant by "Moore's apartment," and

what factual basis, if any, there was for believing that Moore was a tenant or

regular resident there. Moore was similarly deprived of the chance to show that

the witness' recollection was erroneous or that he was not credible.1 The

informant's declaration falls within no exception to the hearsay rule recognized

in the Federal Rules of Evidence, and reliance on this hearsay statement in

determining petitioner's guilt or innocence was error.2

Although the only competent evidence of Moore's possession of the narcotics

was his proximity to them in an apartment in which another person was also

present and of which he was not shown to be the tenant or even a regular

resident, the Solicitor General now argues that the error in admitting the

hearsay evidence was harmless. That is far from clear. Whether or not the

evidence of proximity alone, when viewed in the light most favorable to the

prosecution, could suffice to prove beyond a reasonable doubt that Moore was

in possession of the heroin, the fact is that the trial court did not find Moore

guilty on that evidence alone.

10

(2) The Government suggests that Moore's failure to testify or to adduce any

evidence showing "that his presence in the apartment was unrelated to the

heroin" highlights the alleged harmlessness of the error, but this suggestion can

carry no weight in view of the elementary proposition that the prosecution bore

the burden of proving beyond a reasonable doubt every element of the charged

offense. Equally unpersuasive is the Government's argument that the error was

probably harmless because Moore was convicted in a bench trial; whatever the

merits of that argument as a general proposition, it has a hollow ring in a case

where the trial judge expressly relied upon the inadmissible evidence in finding

the defendant guilty.

11

The petition for a writ of certiorari is granted, the judgment of the Court of

Appeals is vacated, and the case is remanded to that court so it may determine

whether the wrongful admission of the hearsay evidence was harmless error.3

12

It is so ordered.

13

THE CHIEF JUSTICE, Mr. Justice BLACKMUN, and Mr. Justice

REHNQUIST, dissent from summary reversal and would set the case for oral

argument.

Moore moved to require disclosure of the informant's identity, but the

Government opposed the motion and the trial judge denied it.

Although we do not rely on the Government's confession of error, we note that

the Solicitor General concedes that admission of the hearsay evidence on the

question of Moore's guilt or innocence was improper.

The Government also urges that petitioner's failure to suggest in his closing

argument that consideration of the hearsay evidence be restricted to the

suppression issue constituted a waiver of any objection to the District Judge's

reliance on that evidence in determining guilt or innocence. The Court of

Appeals has not passed on this question, and we leave it for resolution by that

court on remand.

You might also like

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Payn v. Kelley, 10th Cir. (2017)Document8 pagesPayn v. Kelley, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government Docs50% (2)

- United States v. Kieffer, 10th Cir. (2017)Document20 pagesUnited States v. Kieffer, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Olden, 10th Cir. (2017)Document4 pagesUnited States v. Olden, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Garcia-Damian, 10th Cir. (2017)Document9 pagesUnited States v. Garcia-Damian, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government Docs100% (1)

- City of Albuquerque v. Soto Enterprises, 10th Cir. (2017)Document21 pagesCity of Albuquerque v. Soto Enterprises, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Apodaca v. Raemisch, 10th Cir. (2017)Document15 pagesApodaca v. Raemisch, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Consolidation Coal Company v. OWCP, 10th Cir. (2017)Document22 pagesConsolidation Coal Company v. OWCP, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Greene v. Tennessee Board, 10th Cir. (2017)Document2 pagesGreene v. Tennessee Board, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Pecha v. Lake, 10th Cir. (2017)Document25 pagesPecha v. Lake, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Coyle v. Jackson, 10th Cir. (2017)Document7 pagesCoyle v. Jackson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government Docs100% (1)

- Wilson v. Dowling, 10th Cir. (2017)Document5 pagesWilson v. Dowling, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Brown v. Shoe, 10th Cir. (2017)Document6 pagesBrown v. Shoe, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Harte v. Board Comm'rs Cnty of Johnson, 10th Cir. (2017)Document100 pagesHarte v. Board Comm'rs Cnty of Johnson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDocument14 pagesPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government Docs100% (1)

- United States v. Roberson, 10th Cir. (2017)Document50 pagesUnited States v. Roberson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDocument24 pagesPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Document27 pagesUnited States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDocument10 pagesPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Windom, 10th Cir. (2017)Document25 pagesUnited States v. Windom, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Webb v. Allbaugh, 10th Cir. (2017)Document18 pagesWebb v. Allbaugh, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Voog, 10th Cir. (2017)Document5 pagesUnited States v. Voog, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Henderson, 10th Cir. (2017)Document2 pagesUnited States v. Henderson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDocument17 pagesPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Kearn, 10th Cir. (2017)Document25 pagesUnited States v. Kearn, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Northglenn Gunther Toody's v. HQ8-10410-10450, 10th Cir. (2017)Document10 pagesNorthglenn Gunther Toody's v. HQ8-10410-10450, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- NM Off-Hwy Vehicle Alliance v. U.S. Forest Service, 10th Cir. (2017)Document9 pagesNM Off-Hwy Vehicle Alliance v. U.S. Forest Service, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Muhtorov, 10th Cir. (2017)Document15 pagesUnited States v. Muhtorov, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Kundo, 10th Cir. (2017)Document7 pagesUnited States v. Kundo, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Pledger v. Russell, 10th Cir. (2017)Document5 pagesPledger v. Russell, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Document4 pagesUnited States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Donna Horvath, on Behalf of Herself and All Others Similarly Situated v. Keystone Health Plan East, Inc. Donna Horvath, on Behalf of Herself and the Proposed Class She Seeks to Represent, 333 F.3d 450, 3rd Cir. (2003)Document16 pagesDonna Horvath, on Behalf of Herself and All Others Similarly Situated v. Keystone Health Plan East, Inc. Donna Horvath, on Behalf of Herself and the Proposed Class She Seeks to Represent, 333 F.3d 450, 3rd Cir. (2003)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- PEOPLE Vs Edgar VillanuevaDocument5 pagesPEOPLE Vs Edgar VillanuevaAAMCNo ratings yet

- Dr. Lumantas vs. Calapiz G.R. No. 163753, January 15, 2014Document5 pagesDr. Lumantas vs. Calapiz G.R. No. 163753, January 15, 2014FD BalitaNo ratings yet

- Women and Law Project by Mansi BhardwajDocument10 pagesWomen and Law Project by Mansi BhardwajKajal katariaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 4: Fraud: Jovit G. Cain, CPADocument23 pagesChapter 4: Fraud: Jovit G. Cain, CPAJao FloresNo ratings yet

- Garcia v. BOI, 177 SCRA 374 (1989)Document21 pagesGarcia v. BOI, 177 SCRA 374 (1989)Alexandra Zoila Descutido UlandayNo ratings yet

- Notice: Pollution Control Consent Judgments: AbeldgaardDocument1 pageNotice: Pollution Control Consent Judgments: AbeldgaardJustia.comNo ratings yet

- Spouses Cha Vs CADocument2 pagesSpouses Cha Vs CACarlyn Belle de GuzmanNo ratings yet

- U.Republic V Acoje MiningDocument3 pagesU.Republic V Acoje MiningCharlene MillaresNo ratings yet

- Key Players in Criminal Investigation: Psinsp Conrado R de Vera JR, DPMDocument29 pagesKey Players in Criminal Investigation: Psinsp Conrado R de Vera JR, DPMJohn Bernardo86% (7)

- Rural Bank v. CADocument1 pageRural Bank v. CAKeren del RosarioNo ratings yet

- Tips For Writing Good Legal Research Papers and EssaysDocument3 pagesTips For Writing Good Legal Research Papers and EssaysAlan WhaleyNo ratings yet

- Atty Suspended for Demanding Bribes in Land RegistrationDocument27 pagesAtty Suspended for Demanding Bribes in Land RegistrationGe LatoNo ratings yet

- Affidavit For NICOP No Passport Online ApplicationDocument1 pageAffidavit For NICOP No Passport Online Applicationattiya kalairNo ratings yet

- Sayco vs. PeopleDocument12 pagesSayco vs. PeopleWilfredNo ratings yet

- Family Law II NotesDocument10 pagesFamily Law II NotesAnirudh SoodNo ratings yet

- Oblicon CasesDocument13 pagesOblicon CasescmdelrioNo ratings yet

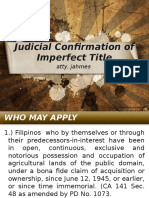

- Land Titles - Judicial Confirmation of Imperfect TItle-Orig Reg StepsDocument53 pagesLand Titles - Judicial Confirmation of Imperfect TItle-Orig Reg StepsBoy Kakak Toki86% (7)

- BooginHead v. Cheeky Chompers - ComplaintDocument17 pagesBooginHead v. Cheeky Chompers - ComplaintSarah BursteinNo ratings yet

- TFS, Incorporated Vs CIR, GR 166829, April 19, 2010Document2 pagesTFS, Incorporated Vs CIR, GR 166829, April 19, 2010katentom-1No ratings yet

- Digest - Tai Tong Chuache & Co Vs Insurance Commission Et AlDocument3 pagesDigest - Tai Tong Chuache & Co Vs Insurance Commission Et Alapi-263595583No ratings yet

- PhilGEPS Sworn Statement - 1102Document2 pagesPhilGEPS Sworn Statement - 1102Anonymous 19OHEg783% (29)

- Labor Relations NotesDocument36 pagesLabor Relations Notesdave_88opNo ratings yet

- Nickoyan Nkrumah Wallace, A041 654 413 (BIA Feb. 26, 2016)Document9 pagesNickoyan Nkrumah Wallace, A041 654 413 (BIA Feb. 26, 2016)Immigrant & Refugee Appellate Center, LLCNo ratings yet

- Court of Appeals upholds ownership of disputed propertiesDocument258 pagesCourt of Appeals upholds ownership of disputed propertieshachi15No ratings yet

- Regalado V RegaladoDocument11 pagesRegalado V RegaladoJay RibsNo ratings yet

- Republic vs. Sandiganbayan, 540 SCRA 431 (2007)Document13 pagesRepublic vs. Sandiganbayan, 540 SCRA 431 (2007)seth3caballesNo ratings yet

- Sample LP of Practical Research 1Document3 pagesSample LP of Practical Research 1Jesamie Bactol SeriñoNo ratings yet

- Solinap v. Del RosarioDocument2 pagesSolinap v. Del RosarioNico Delos Trinos100% (1)

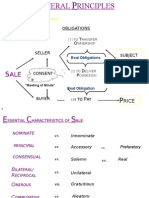

- Sales PrezoDocument51 pagesSales PrezoyanyanNo ratings yet