Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Function of Phosphate in Alcoholic Fermentation: Nobel Lecture, December 12, 1929

Uploaded by

hartmann100Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Function of Phosphate in Alcoholic Fermentation: Nobel Lecture, December 12, 1929

Uploaded by

hartmann100Copyright:

Available Formats

A RTHUR H ARDEN

The function of phosphate in alcoholic fermentation

Nobel Lecture, December 12, 1929

The discovery that phosphates play an essential part in alcoholic fermentation

arose of an attempt by the late Dr. Allan Macfadyen to prepare an anti-zymase

by injecting Buchners yeast-juice into animals. As a necessary preliminary

to the study of the effect of the serum of these injected animals on fermentation

by yeast-juice, the action of normal serum was examined. It was thus found

that this exerted a two-fold effect: in its presence the action of the proteolytic

enzymes of the yeast-juice was greatly diminished, and at the same time both

the rate of fermentation and the total fermentation produced were considerably increased. In the course of experiments made to investigate this phenomenon, which it was thought might have been due to the protection of the

enzyme of alcoholic fermentation from proteolysis by means of an antiprotease present in the serum, the effect of boiled autolysed yeast-juice was

tested, it being thought that the presence of the products of proteolysis might

also exert an anti-proteolytic effect. As my colleague Mr. Young, who had by

this time joined me, and myselfhad fortunately decided to abandon the gravimetric method chiefly used by Buchner in favour of a volumetric method

which permitted almost continuous observations, we were at once struck by

the fact that a great but temporary acceleration of the rate of fermentation

and an increase in the CO, evolved proportional to the volume of boiled

juice added were produced. This was ultimately traced to the presence of two

independent factors in the boiled yeast-juice, a thermostable dialysable coenzyme now often known at the suggestion of von Euler as co-zymase, and

inorganic phosphate.

With regard to the phosphate subsequent experiments showed that in all

fermentations brought about by preparations obtained from yeast the presence of phosphate is absolutely essential. Leaving aside the question of living

yeast for consideration later on, three different types of fermentation can be

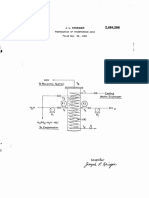

established (See Curves 1, 2, and 3, in Fig. 1) with such preparations.

1. A relatively rapid fermentation (Curve 1, Fig. 1) in which sugar is decomposed into CO2 and alcohol, and simultaneously inorganic phosphate is

converted into an ester (or esters) of a sugar which accumulates. When the

132

1929 A.HARDEN

supply of inorganic phosphate ceases, the rate of fermentation falls, the accumulation of ester also naturally ceases, and the fermentation passes into Type 2.

2. A relatively slow fermentation (Curve 2, Fig. 2) in which the rate at

which fermentation occurs is controlled by the rate at which inorganic phosphate is supplied by the hydrolysis of the phosphoric esters present in the

system by the phosphatase also present. This inorganic phosphate is alternately

reconverted into a sugar-phosphoric ester and again liberated by hydrolysis,

and thus fermentation proceeds at a steady rate in the presence of available

sugar without any permanent increase in the amount of inorganic phosphate

or of phosphoric ester present. This is the type of fermentation which goes

on when sugar is added to an active preparation from yeast and the process is

allowed to proceed until a steady rate is obtained. In some preparations, depending on the amount of phosphatase present, the rate of fermentation is

increased to some extent if more of the sugar-phosphoric ester is added or

produced (See E. Boyland, Biochem. J., 23 (1929) 219), but this soon reaches

a limit. If inorganic phosphate be added, the fermentation passes into Type 1.

If sugar fails, inorganic phosphate appears and ultimately (unter favourable

conditions) the whole of the sugar-phosphoric ester is hydrolysed, its sugar

moiety fermented and the whole of the phosphate liberated in the inorganic

form.

3. If now into a fermentation mixture in which a Type 2 fermentation is

PHOSPHATE IN ALCOHOLIC FERMENTATION

133

proceeding an additional quantity be introduced of a phosphatase, capable of

hydrolysing the sugar-phosphoric ester and thus increasing the rate of supply

of inorganic phosphate (Harden and Macfarlane, unpublished results), the

rate of fermentation also rises. If a sufficiently active preparation of phosphatase could be added, so that the sugar-phosphoric ester was decomposed

as rapidly as it was formed, a rapid fermentation would ensue, unaccompanied

by accumulation of phosphoric ester. This has not yet been accomplished

directly, but an indirect method of attaining the same end is available, inasmuch as arsenates have been found to have the power of greatly stimulating

the effect of the phosphatase. This observation was in reality the undeserved

reward for thinking chemically about a biochemical problem. In many chemical reactions the type of compound concerned is the main fact of importance,

arsenates react like phosphates, potassium may be replaced by sodium, iron

by nickel or cobalt. Biochemically the difference between potassium and sodium may be the difference between life and death, and when iron is not used

in a respiratory pigment it is not replaced in nature by nickel or cobalt, but

by copper or vanadium. So, also, arsenate does not play a similar part to phosphate in fermentation, but acts in an entirely different manner. On the addition of a suitable amount of arsenate, a rapid fermentation (Curve 3, Fig. 1)

occurs comparable in rate with that of Type 1, but differing from this in that

the rate is permanently raised and that no accumulation of the sugar-phosphoric ester occurs. Under optimal conditions the addition of inorganic phosphate does not produce any significant rise in the rate of fermentation, as the

rate of fermentation is controlled under these circumstances by the concentration of the fermenting complex (enzymes + co-enzyme). Arsenate on the

other hand does not increase the maximum rate in fermentations of Type 1,

as the supply ofinorganic phosphate is already optimal.

Without making any assumption as to the exact nature of the phosphoric

ester actually produced, the changes so far considered may be illustrated by

the two equations, originally proposed by Harden and Young for the case in

which only hexose diphosphate is formed, the first representing the evolution

of CO, and production ofalcohol, accompanied by the accumulation of ester,

and the second the hydrolysis of this ester with liberation of a hexose and

mineral phosphate.

I34

1929 A.HARDEN

Eq. (1) represents the controlling reaction in a fermentation of Type 1, Eq. (2)

that in a fermentation of Type 2. In the presence of arsenate the hydrolysis

of hexose phosphate according to Eq. (2) proceeds sufficiently rapidly to

supply phosphate at such a rate that Eq. ( 1) proceeds at maximum velocity.

Fermentation by living yeast

A striking feature of fermentation by yeast preparations is that it proceeds

much less rapidly than fermentation by a corresponding amount of living

yeast. Thus Buchners yeast-juice ferments at only about 1/2O-r/4,, of the rate

of the yeast from which it is derived.

The fact that the rate of fermentation of such a juice can be raised under

favourable circumstances some 10-20 times simply by increasing the supply

of phosphate seems to me to indicate clearly that a large fraction, at least half,

of the fermenting complex of the yeast has escaped injury in the preparation

and has passed into the juice, but that the mechanism for the supply of inorganic phosphate has been to a large extent destroyed. Neither arsenate nor

phosphate has an accelerating action on the rate of fermentation by living

yeast. This may be due to the fact that the supply of inorganic phosphate in

the interior of the yeast-cell is already optimal, but some doubt exists as to

whether or not these salts freely penetrate the cell. If however, as seems to me

probable, it is true that in the preparation of yeast-juice, etc. it is the phosphatesupplying mechanism that is thrown out of gear, it becomes an object of

enquiry in what way this is brought about.

Several possibilities present themselves. As suggested for the fermenting

complex itself by von Euler and his colleagues, the phosphatase may in large

part be combined with the cytoplasm and thrown out of action when the cell

is killed. Another possibility is that in the cell the action is localized and that

disorganization of the cell leads to less favourable conditions (e.g. concentration, presence of inhibitors, etc.) and to lessened rate of action. There is some

evidence for this since the amount of phosphatase present, as judged by the

normal rate of fermentation (Type 2), seems to diminish as the disorganization of the cell becomes more complete. Thus dried yeast and yeast dehydrated

with acetone ferment sugar (Type 2) more rapidly than yeast-juice, although

when phosphate is freely supplied they all cause fermentation at about the

same rate. Again some labile substance which acts as an accelerator of the phosphatase may be inactivated by the various modes of treatment (grinding,

PHOSPHATE IN ALCOHOLIC FERMENTATION

135

drying, treatment with toluene or acetone. etc.) to which the cell is subjected.

The process least likely to inactivate an accelerating substance is probably

that used by Buchner, but the possibility also exists that such a substance, if

present, might be adsorbed and thus removed from the juice by the large

quantity of kieselguhr employed.

Experiments (not yet published) have recently been made in my laboratory

by Miss Macfarlane to find out at what stage in the process the change occurs

and whether a juice richer in phosphatase could be obtained by modifying

the process of grinding and pressing out. It appears, however, that simple

grinding with sand produces a change of the same order as that observed in

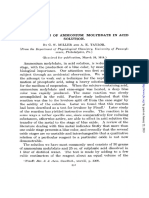

Buchners yeast-juice. The experiments were made by grinding a mixture

of sand and yeast for different times and testing the rate of fermentation and

response to phosphate at intervals of the whole mass without pressing out

(Fig.2).

These curves show the rate of fermentation of 2 g of yeast + 2 g of sand

in 20 C.C. of 10% fructose at 30o : (a) without grinding, (b) after grinding for

20 minutes, and (c) after grinding for 60 minutes. At the point marked with

an arrow 0.6 C.C. of 2 M K2HPO 4 was added.

The curves show that the longer the period of grinding, the lower the rate

of fermentation and the greater the response to phosphate. Here again the

total loss of fermenting power was only small.

Minor differences were observed when different substances were substi-

Fig. 2. Fermentation of yeast sand mixture. (At an addition of phosphate was made.)

136

1929 A.HARDEN

tuted for the kieselguhr used by Buchner, the most active juice for example

being obtained by the use of CaCO3 whereas BaCO3 yielded totally inactive

material.

Further investigation may possibly throw more light on this aspect of the

question.

I have spoken hitherto on the assumption that the processes in the living

cell are essentially of the same kind as those which occur in the various preparations made from the dead cell, but differ from these mainly in the relative

intensity of some of the reactions, and I know no valid argument against this

assumption.

The cycle undergone by the phosphate in the series of changes which constitutes ordinary fermentation clearly consists in the alternate formation of a

phosphoric ester and the hydrolysis of this to free phosphoric acid. A simple

calculation based on the phosphorus content of living yeast shows that the

whole of this phosphate must pass through the stage of phosphoric ester every

five or six minutes in order to maintain the normal rate of fermentation,

whereas in an average sample of yeast-juice the cycle, calculated in the same

way, would last nearly two hours.

Nature and function of the phosphoric esters produced

If we next consider the exact nature of these phosphoric esters and the relation

of their formation and hydrolysis to the decomposition of the sugar molecule,

we are met with a singularly complex condition of affairs, which cannot yet

be interpreted satisfactorily.

The main facts seem to be as follows.

When fermentation of sugar by yeast preparations is carried out under

suitable conditions in presence of added inorganic phosphate, a rapid production of CO2 and alcohol occurs and a phosphoric ester of a sugar accumulates,

the amount of phosphate found in this form being approximately proportional in the ratio (CO2/PO 4 to the increased production of CO2 and alcohol

caused by the addition of the phosphate (Kluyver and Struyk, it is true, have

found lower ratios than this, but there is no doubt that high ratios 0.8-1 are

often observed).

The phosphoric ester produced, however, may consist mainly of the hexose

diphosphate originally described by Young and myself or of the hexose monophosphate described by Robison and myself and subsequently studied by

PHOSPHATE IN ALCOHOLIC FERMENTATION

137

Robison or it may be a mixture of these in any proportions. In the case of

fermentation by dried yeast (and possibly of other preparations) a further

complication is afforded by the fact that a disaccharide-phosphoric ester (trehalose monophosphate) may also be present.

This conclusion is founded in the first place on a large amount of experiencewhich has been gained at the Lister Institute in preparing hexose mono- and

diphosphate. These preparations are as a rule carried out by making repeated

additions of phosphate and sugar to a fermenting mixture of yeast-juice or

dried yeast and fructose (or glucose). With dried yeast a large proportion of

the diphosphate is usually obtained, and the relatively small amount of monophosphate produced contains a considerable proportion of trehalose monophosphate. With yeast-juice the results are very variable and no trehalose

monophosphate has so far been detected among the products. More precise

experiments have been made by Lord Henley and myself in which the gas

evolved after a single addition of phosphate was carefully measured and the

proportions in which mono- and diphosphates were produced were determined as accurately as possible. Unfortunately, the available methods are notvery good, as they rest on the solubilities of the different compounds in 10%

alcohol, and these are to some extent mutually affected in the presence of both

compounds. Further, yeast, like Africa, is always yielding something new,

and the recently discovered fact that pyrophosphates exist in yeast and by

their formation from, or hydrolysis to, orthophosphates may cause disappearance or appearance of "inorganic phosphate" adds another source of inaccuracy to the many previously known.

Allowance has, of course, to be made for the phosphorus compounds existing in the mixture at the moment of addition of inorganic phosphate and

for the normal evolution of CO2 which occurs throughout the experimental

period in addition to the enhanced evolution due to the esterification.

In spite of these minor uncertainties the somewhat surprising fact emerges,

that whatever the nature of the phosphoric ester which accumulates, the CO2

is approximately equivalent in the ratio CO2 : PO4 to the amount of phosphate

which undergoes esterification. The full results are given in two papers published recently by Lord Henley and myself in The Biochemical Journal and need

not be quoted in detail here. The experiments indicate the wide variation

which may occur in the nature of the hexose phosphate produced whilst the

ratio of CO2:PO 4 esterified remains constant and approximately equal to

unity. Two extreme cases may be quoted, in one of which 13.5% of the PO4

esterified was present as hexose diphosphate and 86.5% as monophosphate

138

1929 A.HARDEN

and in the other 97% as diphosphate and only 3% as monophosphate; the

CO2/PO4-esterified ratios were 0.98 and 0.86 respectively.

I do not propose to discuss in any great detail the various theories which have

been proposed to explain these complicated relationships. It would be natural

to assume that the introduction of the phosphoric acid group into the sugar

molecule, forming a hexose monophosphate, might render this more accessible to decomposition into the compound (or compounds) containing three

carbon atoms which are now accepted as an intermediate stage in the production of CO2 and alcohol. The phosphate radical from one of these groups might

then serve to convert another molecule of the monophosphate into the stable

diphosphate (Meyerhof) 2C 6H 11 O5P 04H 2 C 6H Io O4( P 04H 2) 2+ 2CO2 +

+ 2C2H 6O, or two of the th ree carbon groups containing each one phosphate

group might unite with each other, forming the stable diphosphate (Kluyver

and Struyk) 2C6H 11O 5( P O4H 2) 2 C3H 6O 3 + 2C3H 5O 2 ( P O4H 2) 2CO2

+ 2C 2H 6O + C6H 10 O 4 ( P O4H 2) 2. Any monophosphate escaping these reactions would be found as a constituent of the mixed hexose phosphates resulting from the fermentation.

To add further to the dificulty of unravelling this complex tangle it must

be remembered that, whether glucose or fructose be fermented, the hexose

diphosphate produced is probably a derivative of fructose, or at least yields

fructose on hydrolysis, whilst the monophosphate is with equal probability

a mixture of about 80% of a glucose monophosphate and 20% of a fructose

monophosphate. It is obvious from this that whatever changes occur are not

limited to the simple introduction or removal of a phosphoric acid group, fundamental changes occur in the constitution of the molecule of the sugar itself.

Attractive as is the theory of the intermediate character of some one of the

hexose phosphates, it seems to me impossible at the moment to bring it into

agreement with some of the facts which have just been related. The production of 70-80% of the monophosphate, with an unaltered degree offormation

of alcohol and CO2, renders it impossible that this ester should be "obviously

nothing but a part of the intermediate product which has escaped the coupled

decomposition-esterification reaction" (O.Meyerhof and K. Lohmann,

Biochem. Z., 185 (1927) 155).

It appears to me that the fundamental idea expressedin the original equation

of Harden and Young is nearer the truth than any alternative that has as yet

been suggested. A coupled reaction of some kind occurs, as the result of which

the introduction of two phosphate groups into certain sugar molecules - either

into the same molecule or one each into two different ones - induces the de-

PHOSPHATE IN ALCOHOLIC FERMENTATION

139

composition ofanother molecule. The introduction of these phosphate groups

in presence of muscle extract and presumably in both muscle itself and yeast,

is actually accompanied by a small evolution of heat (O. Meyerhof and J.

Suranyi, Biochem. Z., 191 (1927) 106), and it is possible that this may have

some significance for the occurrence of the coupled reaction. What are the

conditions for the preferential formation of the mono- or di-ester we do not

yet certainly know, although the work of Kluyver and Struyk suggests that

dilution of the enzyme may be one factor in this.

The lack of exact chemical equivalence among the products (ester on the

one hand, CO2 and alcohol on the other) is probably more easily explicable

on this view than on any other.

The mechanism of the fermentation of the monoester has not yet been

worked out in sufficient detail to afford valid evidence either for or against

the theory, but Dr. Robison and I have made experiments (about to be published) which show that the monophosphate itself reacts with a further quantity of phosphate and that this reaction is accompanied by an enhanced production of carbon dioxide and alcohol.

Sugar metabolism in vegetable ad animal organisms

After the establishment of the important part played by phosphates and phosphoric esters in alcoholic fermentation, it was soon found by various workers

that these compounds provided the clue to many other biological phenomena.

The co-zymase of alcoholic fermentation was found by Meyerhof to exert

an equally important part in the respiration of yeast, and the important observation was made also by Meyerhof that it occurred in muscle and was an

essential factor in the carbohydrate metabolism of muscle, in which the intervention of a hexose phosphate had been proved by Embden. This phenomenon was shown to take place on lines quite similar to those of the respiration

and fermentation of yeast, and in 1924, before the riddle of lactic acid formation had been completely solved, O. Meyerhof wrote (Chemical Dynamics

of Life Phenomena, 1924) : "It may indeed be considered a success of general

physiology and its mode of experimenting, that the chemical dynamics of a

highly differentiated organ like the muscle could be partly revealed by the

study of alcoholic fermentation of yeast." But a still greater success was to

follow. An astonishing degree ofsimilarity was shown to exist between almost

every detail of the production of lactic acid by the muscle enzymes and of

140

1929 A.HARDEN

alcohol by the yeast enzyme, which extended to the identity of the phosphoric esters concerned, the accumulation of ester under similar conditions,

and even to the effect of arsenate on the process. After the publication of

Meyerhofs preliminary papers in which these observations were recorded I

wrote the following passage in concluding a short review of the work (Nature, 118 (1926) Dec. 18th) which I may perhaps be allowed to quote: "The

striking similarity established by Meyerhof between the changes of carbohydrates in muscle and in the yeast cell is seen to be much closer than has been

believed. The remarkable phenomena accompanying alcoholic fermentation

are now duplicated in the case of lactic acid production, and it may reasonably

be expected that most of the fermentative decompositions of the sugars will

be found to be initiated in a similar manner"

Direct proof is still wanting in many cases, but some instances are known

among bacteria (Virtanen), moulds (von Euler and Kullberg) and higher

plants (Ivanoff, Bodnar). It is not too much to say that the fundamental biological mode of attack on carbohydrates is that revealed by the study of alcoholic fermentation.

Ossification

Another biochemical function of the hexose phosphates which is shared by

other hydrolysable phosphoric esters is that of being a potential source of

phosphate ions. I am happy to say that one of the most beautiful and important

developments of this idea has been worked out quite independently at the

Lister Institute by Dr. R. Robison as a direct consequence of his work on the

hexose monophosphate of yeast-juice.

"During my investigation of the hexose monophosphoric acid isolated

from the products of fermentation", he says (Biochem. ]., 17 (1923) 286) "the

hydrolysis of the ester by enzymes was studied. In some experiments in which

the readily soluble calcium and barium salts were used as substrates, the progress of the hydrolysis was shown by the formation of a precipitate of sparingly soluble calcium or barium phosphate

C6H,,0jP0,Ca+H,0 -+ C6Hrz0,j+ CaHPO,

The formation of this precipitate suggested to me the query whether some

such reaction might conceivably be concerned in the deposition of calcium

phosphate during the formation of bone in the animal body. In the first place I

PHOSPHATE IN ALCOHOLIC FERMENTATION

141

sought for an enzyme capable of effecting hydrolysis in the bones of growing

animals."

The search was successful, a "bone phosphatase" was found in the ossifying

cartilage of young animals and a series of interesting and important investigations has followed, as a result of which I have little doubt that their author is

on the highway to the chemical explanation of the process of ossification - a

good instance of the far-reaching and unexpected results flowing from observations made for quite a different purpose.

You might also like

- Phosphates Recovery from Iron Phosphates Sludge via Anaerobic Biological ProcessDocument21 pagesPhosphates Recovery from Iron Phosphates Sludge via Anaerobic Biological ProcessNatashaEgiearaNo ratings yet

- FosfatasaDocument13 pagesFosfatasasimon.ignacio.jNo ratings yet

- Phosphatases and The Utilization of Organic Phosphorus by RhizobiumDocument3 pagesPhosphatases and The Utilization of Organic Phosphorus by RhizobiumSudipSilwalNo ratings yet

- Phosphate Hideout PDFDocument4 pagesPhosphate Hideout PDFAHMAD DZAKYNo ratings yet

- Phosphate Hideout PDFDocument4 pagesPhosphate Hideout PDFUsama JawaidNo ratings yet

- J. Biol. Chem.-1933-Folin-111-25Document16 pagesJ. Biol. Chem.-1933-Folin-111-25Nitya Nurul FadilahNo ratings yet

- Biochem OnlinDocument5 pagesBiochem Onlinchughtais.health.aidNo ratings yet

- US3936501Document3 pagesUS3936501qaim abbasNo ratings yet

- Phispate 3Document5 pagesPhispate 3XX GUYNo ratings yet

- Lynen LectureDocument36 pagesLynen LectureСоња БакраческаNo ratings yet

- Yeast Fermentation Lab - Lily Grant - SBI4U - Ms. JephcottDocument6 pagesYeast Fermentation Lab - Lily Grant - SBI4U - Ms. Jephcott6zzn89vqh6No ratings yet

- Bio FermentationDocument8 pagesBio FermentationCecil ClaveriaNo ratings yet

- Purification of Insulin Yields a Hydrochloride With Strong Biuret & Pauly ReactionsDocument15 pagesPurification of Insulin Yields a Hydrochloride With Strong Biuret & Pauly ReactionskashvinwarmaNo ratings yet

- Materials: Experiment 5. Enzyme Assay Materials and MethodsDocument2 pagesMaterials: Experiment 5. Enzyme Assay Materials and MethodsKamille BrouwersNo ratings yet

- Yeast's Selective Fermentation of Glucose and FructoseDocument5 pagesYeast's Selective Fermentation of Glucose and FructosekepetrosNo ratings yet

- Jurnal 10Document17 pagesJurnal 10Daniall AbdanNo ratings yet

- LabREPORT 7Document5 pagesLabREPORT 7Abdelaziz N. MaldisaNo ratings yet

- July 20, 1954 J. L. Krieger 2,684,286: InventorDocument4 pagesJuly 20, 1954 J. L. Krieger 2,684,286: InventorNurhafizah Abd JabarNo ratings yet

- Sevoflurane, USP: Volatile Liquid For InhalationDocument35 pagesSevoflurane, USP: Volatile Liquid For InhalationIyannyanNo ratings yet

- Mekanisme Pupuk Pada TanahDocument12 pagesMekanisme Pupuk Pada TanahPutri Indra NovianiNo ratings yet

- Phospho Ketolase PathwayDocument2 pagesPhospho Ketolase PathwayShiva100% (6)

- A Universal Method For Preparing Nutrient Solutio-Wageningen University and Research 309364Document22 pagesA Universal Method For Preparing Nutrient Solutio-Wageningen University and Research 309364Rómulo Del ValleNo ratings yet

- I. The Role of Pyruvate As An Intermediate Bruno Rosenfeld Ernst SimonDocument11 pagesI. The Role of Pyruvate As An Intermediate Bruno Rosenfeld Ernst SimonreynaldiNo ratings yet

- THE FUCHSIN-SULFUROUS ACID TEST FOR HEPARIN AND ALLIED POLYSACCHARIDESDocument6 pagesTHE FUCHSIN-SULFUROUS ACID TEST FOR HEPARIN AND ALLIED POLYSACCHARIDESJoena Mae G. DavidNo ratings yet

- Fermentation Processes Ecological DistributionDocument10 pagesFermentation Processes Ecological DistributionEduar Moreno LondoñoNo ratings yet

- Protein Synthesis in Avocado Fruit Tissue PDFDocument4 pagesProtein Synthesis in Avocado Fruit Tissue PDFdr.sameer sainiNo ratings yet

- Wright: Kefnneth EDocument9 pagesWright: Kefnneth ECipta WijayaNo ratings yet

- Pranggawan, 171 - 59-65Document7 pagesPranggawan, 171 - 59-65sitihadirarosmalianaNo ratings yet

- Phospho Ketolase PathwayDocument2 pagesPhospho Ketolase PathwayRisa DedewwNo ratings yet

- Phosphoric Acid Toxicity and ExposureDocument2 pagesPhosphoric Acid Toxicity and ExposurePeter HendraNo ratings yet

- History: Purpose The Oxidative-Fermentative Test Is Used To Determine If Gram-NegativeDocument3 pagesHistory: Purpose The Oxidative-Fermentative Test Is Used To Determine If Gram-NegativeSujit ShandilyaNo ratings yet

- QUANTITATIVE DETERMINATION OF BENZOIC, HIPPURIC, AND PHENACETURIC ACIDSDocument10 pagesQUANTITATIVE DETERMINATION OF BENZOIC, HIPPURIC, AND PHENACETURIC ACIDSIMsc NitpNo ratings yet

- Biological phosphorus removal: principles and EBPR processDocument6 pagesBiological phosphorus removal: principles and EBPR processUmmiey SyahirahNo ratings yet

- Phosphate Hideout: Questions and AnswersDocument4 pagesPhosphate Hideout: Questions and AnswersSivakumar Rajagopal100% (3)

- Role of Microorganisms in Phosphorus CyclingDocument3 pagesRole of Microorganisms in Phosphorus CyclingGOWTHAM GUPTHA100% (3)

- A Universal Method For Preparing Nutrient Solutions of A Certain Desired CompositionDocument21 pagesA Universal Method For Preparing Nutrient Solutions of A Certain Desired CompositionWilliamQuantrillNo ratings yet

- Phospho Ketolase PathwayDocument2 pagesPhospho Ketolase PathwayDr. SHIVA AITHALNo ratings yet

- Ex PhosphonatesDocument1 pageEx PhosphonatesBapu ReddyNo ratings yet

- The Effect of The Nature of Substrate On The Rate of Cellular Respiration in YeastDocument9 pagesThe Effect of The Nature of Substrate On The Rate of Cellular Respiration in YeastAbe CeasarNo ratings yet

- Enzyme Biochem Lab KGDocument13 pagesEnzyme Biochem Lab KGKimberly George-Balgobin50% (2)

- Jphysiol 1897 sp000678Document7 pagesJphysiol 1897 sp000678Isam SalehNo ratings yet

- مقالة40Effect of pH and Calcium Concentration on Proteolysis in Mozzarella CheeseDocument9 pagesمقالة40Effect of pH and Calcium Concentration on Proteolysis in Mozzarella CheeseMohamad AlshehabiNo ratings yet

- Inhibición de La Fermentación Maloláctica en Saccharomyces Con Niveles Bajos y Altos de Nitrógeno (Estudio en Medio Sintético)Document10 pagesInhibición de La Fermentación Maloláctica en Saccharomyces Con Niveles Bajos y Altos de Nitrógeno (Estudio en Medio Sintético)sandraNo ratings yet

- Composition of saliva: Organic and inorganic componentsDocument11 pagesComposition of saliva: Organic and inorganic componentsKaren Daphne Yu NamuagNo ratings yet

- (Mazza 1933) - PH: J. J. and H. Macy and andDocument14 pages(Mazza 1933) - PH: J. J. and H. Macy and andSwati2013No ratings yet

- BY AND: This Is An Open Access Article Under The LicenseDocument7 pagesBY AND: This Is An Open Access Article Under The LicenseKath RodríguezNo ratings yet

- Mechanism of Cytoplasmatic PH Regulation in Hypoxic Maize Root Tips and Its Role in Survival Under HypoxiaDocument5 pagesMechanism of Cytoplasmatic PH Regulation in Hypoxic Maize Root Tips and Its Role in Survival Under HypoxiaGabriel ZahariaNo ratings yet

- English Mythology ReviewerDocument5 pagesEnglish Mythology ReviewerAngelika JimeneaNo ratings yet

- Vol. 7I Human Seminal Acid Phosphatase 233: TransportDocument10 pagesVol. 7I Human Seminal Acid Phosphatase 233: TransportAlishba KaiserNo ratings yet

- J. Biol. Chem.-2000-Avilan-9447-51Document5 pagesJ. Biol. Chem.-2000-Avilan-9447-51Fatma ZorluNo ratings yet

- On Reduction of Ammonium Molybdate in Acid SolutionDocument7 pagesOn Reduction of Ammonium Molybdate in Acid Solutionthrowaway456456No ratings yet

- Phytic Acid: From The Piusbury Company, Minneapolis, MinnesotaDocument4 pagesPhytic Acid: From The Piusbury Company, Minneapolis, MinnesotaMd Jahidul IslamNo ratings yet

- Boiler Phosphate HideoutDocument3 pagesBoiler Phosphate Hideoutzeeshan100% (1)

- 4500-P Phosphorus : 1. OccurrenceDocument16 pages4500-P Phosphorus : 1. OccurrenceOlgaNo ratings yet

- Pettenkofer Test Detects Bile Acids with Sulfuric AcidDocument2 pagesPettenkofer Test Detects Bile Acids with Sulfuric AcidGecai Osial67% (3)

- ChemDocument16 pagesChemRajat UpadhyayNo ratings yet

- Articulsobre MicroDocument5 pagesArticulsobre Micro11259252No ratings yet

- Protein & BoneDocument3 pagesProtein & BoneJoel LopezNo ratings yet

- Biochemistry Applied to Beer Brewing - General Chemistry of the Raw Materials of Malting and BrewingFrom EverandBiochemistry Applied to Beer Brewing - General Chemistry of the Raw Materials of Malting and BrewingRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- A Further Investigation of the Symmetrical Chloride of Paranitroorthosulphobenzoic AcidFrom EverandA Further Investigation of the Symmetrical Chloride of Paranitroorthosulphobenzoic AcidNo ratings yet

- Adventures in The Hollow Earth - Rob SchwarzDocument27 pagesAdventures in The Hollow Earth - Rob Schwarzpgeorg100% (3)

- EU EEA Optometrist Form 2016Document29 pagesEU EEA Optometrist Form 2016hartmann100No ratings yet

- The Origin of Radar at the Naval Research Laboratory: A Case Study in Mission-Oriented R&DDocument222 pagesThe Origin of Radar at the Naval Research Laboratory: A Case Study in Mission-Oriented R&Dhartmann100No ratings yet

- Ada 095571Document892 pagesAda 095571hartmann100No ratings yet

- Unclassified Ad Number Classification Changes TO: From: Limitation Changes TODocument32 pagesUnclassified Ad Number Classification Changes TO: From: Limitation Changes TOhartmann100No ratings yet

- Wal 710 - 492Document20 pagesWal 710 - 492killkess1979No ratings yet

- Unclassified Ad Number Classification ChangesDocument144 pagesUnclassified Ad Number Classification Changeshartmann100No ratings yet

- Ada 954868Document30 pagesAda 954868hartmann100No ratings yet

- The Roots of The Command and Control of Air Power: An Appraisal of Three Air Forces Through 1945Document421 pagesThe Roots of The Command and Control of Air Power: An Appraisal of Three Air Forces Through 1945hartmann100No ratings yet

- Unclassified Ad Number: AuthorityDocument185 pagesUnclassified Ad Number: Authorityhartmann100No ratings yet

- Ugl - Ssii Date: LaboratoryDocument10 pagesUgl - Ssii Date: Laboratoryhartmann100No ratings yet

- Unclassified Ad Number: AuthorityDocument205 pagesUnclassified Ad Number: Authorityhartmann100No ratings yet

- Ada800749 PDFDocument23 pagesAda800749 PDFhartmann100No ratings yet

- Microcomputer-Based Shipboard Gun Control SystemDocument588 pagesMicrocomputer-Based Shipboard Gun Control Systemhartmann100No ratings yet

- Unclassified Ad Number Classification ChangesDocument144 pagesUnclassified Ad Number Classification Changeshartmann100No ratings yet

- Unclassified Ad Number Classification Changes TO: From: Limitation Changes TODocument32 pagesUnclassified Ad Number Classification Changes TO: From: Limitation Changes TOhartmann100No ratings yet

- Ad 0366717Document255 pagesAd 0366717hartmann100No ratings yet

- Ceramic Electron Devices: Metallurgical Research and DevelopmentDocument502 pagesCeramic Electron Devices: Metallurgical Research and Developmenthartmann100No ratings yet

- English Old Norse DictionaryDocument0 pagesEnglish Old Norse DictionaryTomas Branislav PolakNo ratings yet

- B 954297Document42 pagesB 954297hartmann100No ratings yet

- Unclassified Ad Number: AuthorityDocument132 pagesUnclassified Ad Number: Authorityhartmann100No ratings yet

- Ada 954868Document30 pagesAda 954868hartmann100No ratings yet

- Ad 0366704Document130 pagesAd 0366704hartmann100No ratings yet

- Ad 0366704Document130 pagesAd 0366704hartmann100No ratings yet

- A 438002Document59 pagesA 438002hartmann100No ratings yet

- Historical Development Summary of Automatic Cannon Caliber Ammunition 20-30mm by Dale DavisDocument215 pagesHistorical Development Summary of Automatic Cannon Caliber Ammunition 20-30mm by Dale DavisAmmoResearchNo ratings yet

- Ad 0214199 EFFECT OF DIRECTIONAL PROPERTIES IN RHADocument18 pagesAd 0214199 EFFECT OF DIRECTIONAL PROPERTIES IN RHAhartmann100No ratings yet

- Ada 800118Document214 pagesAda 800118hartmann100No ratings yet

- Unclassified Ad Number: AuthorityDocument62 pagesUnclassified Ad Number: Authorityhartmann100No ratings yet

- Top Alkene and Alkyne ReactionsDocument11 pagesTop Alkene and Alkyne ReactionsKristineNo ratings yet

- Temperance MovementDocument7 pagesTemperance Movementapi-603240861No ratings yet

- Difped 24 JunDocument68 pagesDifped 24 JunlakittychidaNo ratings yet

- Project Report On Microbrewery & Imfl DistillationDocument10 pagesProject Report On Microbrewery & Imfl DistillationEIRI Board of Consultants and PublishersNo ratings yet

- Msds PDFDocument6 pagesMsds PDFAlit IstianiNo ratings yet

- Fluid Phase Equilibria: Alexis R. Velez, J. Romina Mufari, Laura J. RovettoDocument9 pagesFluid Phase Equilibria: Alexis R. Velez, J. Romina Mufari, Laura J. RovettoMeMrAnonymousNo ratings yet

- Hardin S.Si, S.PD, M.PDDocument26 pagesHardin S.Si, S.PD, M.PDRadiatul Awalia AmirNo ratings yet

- The Bartenders Field Manual Free Chapters 1 PDFDocument27 pagesThe Bartenders Field Manual Free Chapters 1 PDFLeivaditisNikos0% (2)

- Microbiological Aspects of Ozone Applications in Food: A ReviewDocument11 pagesMicrobiological Aspects of Ozone Applications in Food: A ReviewNanda Dwi WigrhianaNo ratings yet

- Sample Script of An Initial Brief Alcohol Counseling SessionDocument6 pagesSample Script of An Initial Brief Alcohol Counseling SessionEmilly CabaneroNo ratings yet

- Topic 15 Organic Chemistry: Carbonyls, Carboxylic Acids and ChiralityDocument9 pagesTopic 15 Organic Chemistry: Carbonyls, Carboxylic Acids and ChiralitysalmaNo ratings yet

- Chemistry: GCE Ordinary Level (2017) (Syllabus 5073)Document30 pagesChemistry: GCE Ordinary Level (2017) (Syllabus 5073)hadysuciptoNo ratings yet

- Basic Organic ChemistryDocument78 pagesBasic Organic Chemistry2E (04) Ho Hong Tat AdamNo ratings yet

- AHTN2022 CHAPTER22 wNOTESDocument5 pagesAHTN2022 CHAPTER22 wNOTESdoookaNo ratings yet

- 134 Data SheetDocument4 pages134 Data SheetcarlosNo ratings yet

- Organometallic Compounds: Guest Lecturer: Prof. Jonathan L. SesslerDocument40 pagesOrganometallic Compounds: Guest Lecturer: Prof. Jonathan L. Sesslerhera hmNo ratings yet

- SF Gosling S 7 Generations Engl.Document2 pagesSF Gosling S 7 Generations Engl.s_schreweNo ratings yet

- Questions About DensityDocument8 pagesQuestions About DensityJohn OsborneNo ratings yet

- Kerala Price List 2020 PDFDocument171 pagesKerala Price List 2020 PDFVivekanand BalijepalliNo ratings yet

- Previous HSE Questions From The Chapter "Alcohols, Phenols and Ethers"Document3 pagesPrevious HSE Questions From The Chapter "Alcohols, Phenols and Ethers"Nikhil MathewNo ratings yet

- Cooper FiberglassDocument52 pagesCooper FiberglassOzan AtıcıNo ratings yet

- Cascade Orange Coriander Pale AleDocument1 pageCascade Orange Coriander Pale AleRade StevanovicNo ratings yet

- Brand Ambassador Directory v7 - 2019.09.25Document101 pagesBrand Ambassador Directory v7 - 2019.09.25baroneiNo ratings yet

- GK MCQ: Chemistry: Gurudwara Road Model Town, Hisar 9729327755Document24 pagesGK MCQ: Chemistry: Gurudwara Road Model Town, Hisar 9729327755megarebelNo ratings yet

- Bar Terms ExplainedDocument11 pagesBar Terms ExplainedMark Angelo SalazarNo ratings yet

- Pyridinium chlorochromate oxidation of primary and secondary alcoholsDocument4 pagesPyridinium chlorochromate oxidation of primary and secondary alcoholsmario840No ratings yet

- Click To Edit Master Subtitle StyleDocument31 pagesClick To Edit Master Subtitle StyleMA Orejas RamosNo ratings yet

- Aieee Sample PaperDocument25 pagesAieee Sample PaperEdukondalu NamepalliNo ratings yet

- Huntsman Water 251013Document34 pagesHuntsman Water 251013johann69009No ratings yet

- Kingfisher Beer NewDocument45 pagesKingfisher Beer NewCyogi23No ratings yet