Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Van Os 2016 BMJ 'Schizophrenia' Does Not Exist

Uploaded by

hselageaCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Van Os 2016 BMJ 'Schizophrenia' Does Not Exist

Uploaded by

hselageaCopyright:

Available Formats

BMJ 2016;352:i375 doi: 10.1136/bmj.

i375 (Published 2 February 2016)

Page 1 of 2

Views & Reviews

VIEWS & REVIEWS

PERSONAL VIEW

Schizophrenia does not exist

Disease classifications should drop this unhelpful description of symptoms

Jim van Os full professor and chair, Department of Psychiatry and Psychology, Maastricht University

Medical Centre, PO Box 616, 6200 MD Maastricht, Netherlands

In March 2015 a group of academics, patients, and relatives

published an opinion piece in a national newspaper in the

Netherlands, proposing that we drop the essentially contested1

term schizophrenia, with its connotation of hopeless chronic

brain disease, and replace it with something like psychosis

spectrum syndrome.2

We launched two websites (www.schizofreniebestaatniet.nl/

english/ and www.psychosenet.nl) aimed at informing the public

about the nature of psychotic illness and helping patients deal

with pervasive, unscientifically pessimistic, organic views of

their symptoms. The timing was no coincidence.

Several recent papers by different authors have called for

modernised psychiatric nomenclature, particularly regarding

the term schizophrenia.3-6 Japan and South Korea have already

abandoned this term.

Current classifications

The classification of mental disorders, as laid down in ICD-10

(International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision) and

DSM-5 (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders,

fifth edition), is complicated, particularly psychotic illness.

Currently, psychotic illness is classified among myriad

categories, including schizophrenia, schizophreniform disorder,

schizoaffective disorder, delusional disorder, brief psychotic

disorder, depression/bipolar disorder with psychotic features,

substance induced psychotic disorder, and psychotic disorder

not otherwise classified. Categories such as these do not

represent diagnoses of discrete diseases, because these remain

unknown; rather, they describe how symptoms can cluster, to

allow grouping of patients.

This elegant solution allows clinicians to say, for example, You

have symptoms of psychosis and mania, and we classify that

as schizoaffective disorder. If your psychotic symptoms

disappear we may reclassify it as bipolar disorder. If, on the

other hand, your mania symptoms disappear and your psychosis

becomes chronic, we may re-diagnose it as schizophrenia.

That is how our classification system works. We dont know

enough to diagnose real diseases, so we use a system of

symptom based classification. The DSM-5 does this differently

than ICD-10but that does not matter, because its only a

classification.

If everybody agreed to use the terminology in ICD-10 and

DSM-5 in this fashion, there would be no problem. However,

this is not what is generally communicated, particularly

regarding the most important category of psychotic illness:

schizophrenia.

The American Psychiatric Association, which publishes the

DSM, on its website describes schizophrenia as a chronic brain

disorder, and academic journals describe it as a debilitating

neurological disorder,7 a devastating, highly heritable brain

disorder,8 or a brain disorder with predominantly genetic risk

factors.9

Current language suggests discrete

disease

This language is highly suggestive of a distinct, genetic brain

disease. Strangely, no such language is used for other categories

of psychotic illness (schizophreniform disorder, schizoaffective

disorder, delusional disorder, brief psychotic disorder, and so

on). In fact, even though they constitute 70% of psychotic illness

morbidity (only 30% of people with psychotic illness have

symptoms that meet the criteria for schizophrenia),10 these other

categories tend be ignored in the academic literature (see box)

and on websites of professional bodies. They are certainly not

referred to as brain disorders or similar. Its as if they dont

exist.

What remains is the paradox that 30% of psychotic illness

morbidity is portrayed as a discrete brain disease; the other 70%

of the morbidity is communicated only in classification manuals.

Psychosis susceptibility syndrome

Scientific evidence indicates that the different psychotic

categories can be viewed as part of the same spectrum syndrome,

with a lifetime prevalence of 3.5%,10 of which schizophrenia

represents the minority (less than a third) with the poorest

outcome, on average. However, people with this psychosis

spectrum syndromeor, as patients have recently suggested,

vanosj@gmail.com

For personal use only: See rights and reprints http://www.bmj.com/permissions

Subscribe: http://www.bmj.com/subscribe

BMJ 2016;352:i375 doi: 10.1136/bmj.i375 (Published 2 February 2016)

Page 2 of 2

VIEWS & REVIEWS

psychosis susceptibility syndrome6display extreme

heterogeneity, both between and within people, in

psychopathology, treatment response, and outcome.

The best way to inform the public and provide patients with

diagnoses, therefore, is to forget about devastating

schizophrenia as the only category that matters and start doing

justice to the broad and heterogeneous psychosis spectrum

syndrome that really exists.

ICD-11 should remove the term schizophrenia.

Competing interests: I have read and understood the BMJ policy on

declaration of interests and declare the following interests: in the past

five years, the Maastricht University psychiatric research fund that I

manage has received unrestricted investigator led research grants or

recompense for presenting research from Servier, Janssen-Cilag, and

Lundbeck, companies that have an interest in the treatment of psychosis.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer

reviewed.

For personal use only: See rights and reprints http://www.bmj.com/permissions

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

Geekie J, Read J. Making sense of madness: contesting the meaning of schizophrenia.

Routledge, 2009.

Van Os J, Boevink W, Van der Gaag RJ, et al. Laten we de diagnose schizofrenie vergeten

[Lets forget about the diagnosis of schizophrenia]. NRC Handelsblad 2015 Mar 7. www.

chapeau-woonkringen.nl/documenten/artikelen/150307_NRC_Jim_van_Os.pdf. (In Dutch.)

Henderson S, Malhi GS. Swan song for schizophrenia? Aust N Z J Psychiatry

2014;48:302-5.

Lasalvia A, Penta E, Sartorius N, Henderson S. Should the label schizophrenia be

abandoned? Schizophr Res 2015;162:276-84.

Moncrieff J, Middleton H. Schizophrenia: a critical psychiatry perspective. Curr Opin

Psychiatry 2015;28:264-8.

George B, Klijn A. A modern name for schizophrenia (PSS) would diminish self-stigma.

Psychol Med 2013;43:1555-7.

Brennand KJ, Simone A, Jou J, et al. Modelling schizophrenia using human induced

pluripotent stem cells. Nature 2011;473:221-5.

Esslinger C, Walter H, Kirsch P, et al. Neural mechanisms of a genome-wide supported

psychosis variant. Science 2009;324:605.

Goldman AL, Pezawas L, Mattay VS, et al. Widespread reductions of cortical thickness

in schizophrenia and spectrum disorders and evidence of heritability. Arch Gen Psychiatry

2009;66:467-77.

Perala J, Suvisaari J, Saarni SI, et al. Lifetime prevalence of psychotic and bipolar I

disorders in a general population. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2007;64:19-28.

Cite this as: BMJ 2016;352:i375

BMJ Publishing Group Ltd 2016

Subscribe: http://www.bmj.com/subscribe

BMJ 2016;352:i375 doi: 10.1136/bmj.i375 (Published 2 February 2016)

Page 3 of 2

VIEWS & REVIEWS

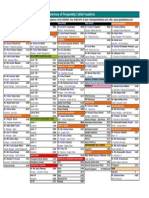

Number of PubMed hits with specific diagnostic categories in the title (November 2015)

Schizophrenia: 51 675

Schizoaffective disorder: 1170

Schizophreniform disorder: 216

Delusional disorder: 212

Brief psychotic disorder: 17

Psychotic disorder (not otherwise specified): 5

Bipolar disorder with psychotic features: 1201

Depression with psychotic features: 409

Substance induced psychotic disorder: 28

For personal use only: See rights and reprints http://www.bmj.com/permissions

Subscribe: http://www.bmj.com/subscribe

You might also like

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Life Overseas 7 ThesisDocument20 pagesLife Overseas 7 ThesisRene Jr MalangNo ratings yet

- Quiz EmbryologyDocument41 pagesQuiz EmbryologyMedShare90% (67)

- fLOW CHART FOR WORKER'S ENTRYDocument2 pagesfLOW CHART FOR WORKER'S ENTRYshamshad ahamedNo ratings yet

- Farid Jafarov ENG Project FinanceDocument27 pagesFarid Jafarov ENG Project FinanceSky walkingNo ratings yet

- Nicenstripy Gardening Risk AssessmentDocument38 pagesNicenstripy Gardening Risk AssessmentVirta Nisa100% (1)

- Laboratorio 1Document6 pagesLaboratorio 1Marlon DiazNo ratings yet

- FinalsDocument8 pagesFinalsDumpNo ratings yet

- UNICESS KR Consmetics Maeteria Nunssupjara 01apr23Document44 pagesUNICESS KR Consmetics Maeteria Nunssupjara 01apr23ZB ChuaNo ratings yet

- Tutorial 7: Electromagnetic Induction MARCH 2015: Phy 150 (Electricity and Magnetism)Document3 pagesTutorial 7: Electromagnetic Induction MARCH 2015: Phy 150 (Electricity and Magnetism)NOR SYAZLIANA ROS AZAHARNo ratings yet

- Impact of Energy Consumption On The EnvironmentDocument9 pagesImpact of Energy Consumption On The Environmentadawiyah sofiNo ratings yet

- Apc 8x Install Config Guide - rn0 - LT - enDocument162 pagesApc 8x Install Config Guide - rn0 - LT - enOney Enrique Mendez MercadoNo ratings yet

- How To Practice Self Care - WikiHowDocument7 pagesHow To Practice Self Care - WikiHowВасе АнѓелескиNo ratings yet

- Maximizing Oredrive Development at Khoemacau MineDocument54 pagesMaximizing Oredrive Development at Khoemacau MineModisa SibungaNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Animal Science For Plant ScienceDocument63 pagesIntroduction To Animal Science For Plant ScienceJack OlanoNo ratings yet

- Schneider Electric PowerPact H-, J-, and L-Frame Circuit Breakers PDFDocument3 pagesSchneider Electric PowerPact H-, J-, and L-Frame Circuit Breakers PDFAnonymous dH3DIEtzNo ratings yet

- Ucg200 12Document3 pagesUcg200 12ArielNo ratings yet

- Cap 716 PDFDocument150 pagesCap 716 PDFjanhaviNo ratings yet

- Insurance Principles, Types and Industry in IndiaDocument10 pagesInsurance Principles, Types and Industry in IndiaAroop PalNo ratings yet

- Iso 28000Document11 pagesIso 28000Aida FatmawatiNo ratings yet

- MEDICO-LEGAL ASPECTS OF ASPHYXIADocument76 pagesMEDICO-LEGAL ASPECTS OF ASPHYXIAAl Giorgio SyNo ratings yet

- RHS NCRPO COVID FormDocument1 pageRHS NCRPO COVID Formspd pgsNo ratings yet

- Q1 Tle 4 (Ict)Document34 pagesQ1 Tle 4 (Ict)Jake Role GusiNo ratings yet

- 2020-11 HBG Digital EditionDocument116 pages2020-11 HBG Digital EditionHawaii Beverage GuideNo ratings yet

- A&P 2 - Digestive System Flashcards - QuizletDocument1 pageA&P 2 - Digestive System Flashcards - QuizletMunachande KanondoNo ratings yet

- Funds Flow Statement ExplainedDocument76 pagesFunds Flow Statement Explainedthella deva prasad0% (1)

- Model Fs CatalogDocument4 pagesModel Fs CatalogThomas StempienNo ratings yet

- WSAWLD002Document29 pagesWSAWLD002Nc BeanNo ratings yet

- Directory of Frequently Called Numbers: Maj. Sheikh RahmanDocument1 pageDirectory of Frequently Called Numbers: Maj. Sheikh RahmanEdward Ebb BonnoNo ratings yet

- M-LVDT: Microminiature Displacement SensorDocument2 pagesM-LVDT: Microminiature Displacement Sensormahdi mohammadiNo ratings yet

- Dip Obst (SA) Past Papers - 2020 1st Semester 1-6-2023Document1 pageDip Obst (SA) Past Papers - 2020 1st Semester 1-6-2023Neo Latoya MadunaNo ratings yet