Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Synthesis Summative-Hekkanen Shawn

Uploaded by

api-324566318Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

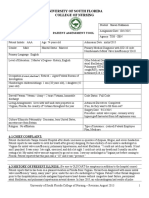

Synthesis Summative-Hekkanen Shawn

Uploaded by

api-324566318Copyright:

Available Formats

Running head: DECREASING BLOOD PRESSURE BY DIET AND EXERCISE

Decreasing High Blood Pressure in Adults by Diet and Exercise

Shawn Hekkanen

University of South Florida

DECREASING BLOOD PRESSURE BY DIET AND EXERCISE

Abstract

Clinical Problem: Patients with high blood pressure have increased risk for first episode, repeat

episodes, or exacerbations of heart attack, heart attack, stroke, and kidney failure.

Objective: To ascertain whether single approaches of diet and exercise or dual approaches of diet

and exercise are effective in sustainably reducing blood pressure. CINAHL, PubMed, and the

National Guideline Clearinghouse were used to gather both studies and guidelines of various

blood pressure reduction techniques. Keywords used for searching include blood pressure,

hypertension, DASH, diet, and exercise.

Results: The clinical guidelines currently recommend diets high in potassium, fiber, and

unsaturated fats are effective for lowering blood pressure (Emergency Care Research Institute

[ECRI], 2013). Exercise guidelines propose at least three times weekly sessions for periods of

30-45 minutes (ECRI, 2013). The literature supported a reduction in blood pressure by either

light to moderate exercise or dietary changes based upon scientifically investigated blood

pressure alleviating dietary components. However, multiple interventions performed

simultaneously has ambivalent results in practical application and needs further research, as does

the most efficient dietary advice that will also be safest for long term health benefits.

Conclusion: Blood pressure was significantly lowered for participants with elevated blood

pressures performing single intervention of diet or exercise, as well as performing both

interventions simultaneously. There is debate whether dual interventions are helpful in all

situations. Further research needs to be performed to pair specific blood pressure complications

to family history. Further research can develop the most efficient dieting and exercise approaches

that are also safe.

DECREASING BLOOD PRESSURE BY DIET AND EXERCISE

Decreasing High Blood Pressure in Adults by Diet and Exercise

Diet and exercise are separately associated with lowering above normal systolic blood

pressure (SBP), which reduces the risk of complications from high blood pressure, such as heart

attack, heart failure, stroke, eye problems, and kidney failure (Agency for Healthcare Research

and Quality, 2014). High blood pressure silently accumulates arterial vessel damage to change

durable elastic walls into rigid, thickened vessels that fail to adequately perfuse the body

(Osborn, Wraa, Watson, & Holleran, 2014). However, clinical symptoms of high blood pressure,

such as chest pain, shortness of breath, and cognition changes, may be delayed for many years

(Osborn et al., 2014). Various laboratory-controlled interventions have been used to improve

persistently high blood pressure, with earlier intervention producing more effective outcomes.

General exercise sessions of 30-45 minutes three times weekly reduce chronic blood pressure

(Osborn et al., 2014). Principles of Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) dieting

consist of eating low-fat or non-fat dairy products, fruits, and vegetables, which are high in

dietary fiber, potassium, magnesium, and calcium (Osborn et al., 2014). DASH principles are

used for intake unsaturated and polyunsaturated sources, with overall lowered fat intake. In nonelderly adults diagnosed with hypertension (P) does a single intervention consisting of a heart

healthy diet or exercise (I) compared to simultaneous interventions of exercise with a hearthealthy diet (C) reduce resting systolic blood pressure levels (O) over four months (T)? The

expected clinical outcome for these patients includes reduced blood pressure levels for all

intervention groups, described as SBP of 120 mmHg. Blood pressure reductions are expected to

be greater in patients performing multiple interventions, both by speed of improvement and

greater improvement achieved overall.

DECREASING BLOOD PRESSURE BY DIET AND EXERCISE

Literature Search

CINAHL, PubMed, and National Guidelines Clearinghouse databases were used to filter

randomized clinical trials and clinical practice guidelines related to arterial hypertension

recommendations for treatment by exercise and nutrition. Keyword terms included blood

pressure, hypertension, DASH, diet, and exercise.

Literature Review

To evaluate the practical application of diet and exercise upon chronic blood pressure,

three randomized controlled trials and one guideline were used. Blumenthal et al. (2010)

conducted a cluster-randomized controlled trial, using groupings of two to five participants, to

study the practical effects of routine DASH dieting and exercise on reducing blood pressures

over a four-month period, while living in the community. Included in this study were 144

participants randomly assigned by computer program into one of two treatment groups or a

control group. Random assignment of groups was equally distributed by participants similarities

of initial blood pressures, body mass indices, and ages. Intervention group one included 46

participants, who used only the DASH diet intervention principles, maintained an equal overall

calorie count from prior to beginning study, and were instructed not to exercise. The control

group included 49 participants, who maintained a diet derived from the calculated average

reported intake of American citizens using the National Health and Nutrition Examination

Survey. Both treatment groups achieved significantly lower SBP than the control group (p<.001).

Blood pressures in the multiple intervention group decreased blood pressure to a level similar to

patients taking antihypertensive medications, and had significantly lower SBP than the DASH

diet-only group (p=.02). The multiple intervention group achieved a reduced SBP by 16.1 mmHg

(95% CI, 13-19.2 mmHg). The DASH diet-only group achieved SBP lowered by 11.2 mmHg

DECREASING BLOOD PRESSURE BY DIET AND EXERCISE

(95% CI, 8.1-14.3 mmHg). The control group reduced blood pressure by 3.4 mmHg (95% CI,

0.4-6.4 mmHg). The study strengths include computer randomization of participant group

assignment concealed from enrollers, experimenters were blind during measurements, groups

were unaware of comparison group differences, reasons were provided for small participant

dropout, standardized manual blood pressure measurement confirmed by simultaneous electronic

measurement used for appropriately defined outcomes, analysis appropriate to group assignment,

appropriateness of control group with verifications for unchanging lifestyle, practical application

among many clinical settings, and appropriate stratification of demographics and initial blood

pressure measurements among groups. The cluster-randomization design controlled outside-thelaboratory factors and limited contamination with intragroup participants that occurred through

observation of each others behaviors during weekly group sessions. A weakness of the study is

the length was too short to track any reduction of cardiovascular events from lowered blood

pressure. Another weakness was possible differences in participant motivation to perform

exercise and dietary interventions in real-world application. The multiple intervention group also

received cognitive-behavioral instruction, which introduced another variable that may have

caused chronic mood alterations that influence blood pressure.

Edwards et al. (2011) used a randomized controlled trial to study the effects of DASH

dieting alone versus DASH dieting with exercise on reducing above-normal blood pressures,

over a three-month period, for sedentary participants living in the community. Included in the

study were 52 participants recruited with SBP of 121-169 mmHg for random assignment

between an exercise-only group, exercise with DASH dieting, and control group. In both

intervention groups, supervised exercise was performed twice weekly with encouragement to

perform another three unsupervised exercise sessions for a maximum of five weekly exercise

DECREASING BLOOD PRESSURE BY DIET AND EXERCISE

sessions. In the multiple intervention group, calories were also restricted by an average of 5001000 calories per day. Both the exercise-only group and DASH dieting with exercise group

achieved significant reductions in resting SBP from pre-intervention to post-intervention when

compared with the non-intervention group (p=.006). A 95% confidence interval was adopted.

Respective SBP reductions occurred of 6.7 mmHg, 12.1 mmHg, and 2 mmHg. However, no

significant difference existed between both intervention groups (p =.053), though the trend

showed greater blood pressure reduction in multiple intervention group. Differences in level of

reduction between both intervention groups were not statistically significant. Study strengths

include computer random assignment of participants, blindness between participant groups and

the relative differences, supervision of workouts was displaced onto instructed YMCA trainers

ignorant of study aim, reasons were given for participant elimination which was primarily

missing two consecutive workout sessions in without performing mandatory makeup session,

valid instruments to measure repeated electronic blood pressures with participant instruction for

consistent orientation during measurement, appropriate control group, evenly distributed

demographics and baseline clinical measures, appropriately tracked clinical outcomes, and

feasible for clinical application. Weaknesses include participant attrition that shrank an already

small sample size and lead to imbalanced stratification of comparison groups that was

augmented via statistical methods, lack of moderately hypertensive and severely hypertensive

participants in overall sample, distribution of participants between groups did not control for age,

short length of study that weakened any summary statement on the overall influence on a

participants health with blood pressure reduction, and the large dropout rate means that

supplementary incentives would be needed to make these interventions appropriate for clinical

application.

DECREASING BLOOD PRESSURE BY DIET AND EXERCISE

Ziv et al. (2013) designed a four-month randomized controlled trial that studied the

effects of the DASH diet with exercise versus a comprehensive blood pressure reduction

approach, using participants receiving antihypertensive medications. The Comprehensive

Approach to Lowering Measured Blood Pressure (CALM-BP) approach included low to

moderate exercise, rice dieting, and relaxation techniques. This diet consists of low protein, low

fat, low sodium and high fiber (Huether & McCance, 2012). All 113 participants were prescribed

at least one antihypertensive medication and had a mean systolic blood pressure between 120180 mmHg. Enrolled participants were randomly assigned to either intervention group and blood

pressure ranges were evenly distributed. Both groups performed exercise for an equal amount of

time. Weekly sessions of relaxation and stress management were included for CALM-BP group.

The participants antihypertensive medication dosages were reduced incrementally if mean SBP

measurements reduced below 110mmHg with reported clinical symptoms of hypotension.

Reduced SBP primarily occurred until week five of CALM-BP group, while SBP reductions

were of a steady reduction rate in DASH group (p<.0001). A 24-hour systolic blood pressure

mean decrease was 4.33 mmHg in CALM-BP group (p=.004) and reduced 4 mmHg in the

DASH group (p=.013), including patients who required a medication reduction.

Antihypertensive medication reductions occurred in 70.7% of CALM-BP participants, while

32.7% of DASH dieters required a medication reduction (p<.0001). Regarding participants who

prescribed a medication reduction from either group, none experienced any further significant

blood pressure reduction after dosage change within the study time period. Strengths of this

study include randomized assignment of groups, participant blindness to activities of comparison

group, participant rate of study completion between above 90% with reasons given for attrition,

appropriated analysis of participants to assigned group, valid electronic instrumentation was used

DECREASING BLOOD PRESSURE BY DIET AND EXERCISE

to measure blood pressure multiple times uniformly, and generalizability to multiple clinical

settings. Weaknesses of the study include lack of participant concealment during randomization

and lack of adequate control group that may did not perform either intervention. An adequate

control group who did not receive any intervention would be important for controlling potential

for psychological effects on blood pressure due to newsworthy events in the community, such as

perceptions of resource availability like gasoline, food, school crowding, etcetera. Another

weakness is demographics and baseline variables were not controlled during random assignment.

Reducing blood pressure guidelines for the prevention of heart attack, stroke, eye

problems, kidney failure, and other complications, were accessed from the National Guidelines

Clearinghouse (ECRI, 2013). The data indicate recommendations for diet and exercise.

Combinations of non-pharmacological measures are not effective. However, a person can be

recommended to start each non-pharmacological measure separately, but it is more clinically

effective to look at sustainability until optimum benefit. Diets rich in fruits and vegetables are

recommended, mostly due to high potassium, but also for fiber. Omega-3 fats can be

recommended up to three times weekly, which are in nuts. Calcium and magnesium supplements

are not generally recommended for hypertension, however, the rice diet is deficient in these

factors to meet recommended daily intake. Recommended exercise includes 30-45 minute

sessions at least three times weekly (ECRI, 2013). Weight loss should be managed by a

professional, an A grade. Controlling stress by itself is not recommended for the treatment of

hypertension, which was a component of Zia et al. (2013).

Synthesis

Blumenthal et al. (2010) reported results that indicated a significant benefit from using

dietary approach alone (p<.001), but both dietary and exercise approaches were significantly

DECREASING BLOOD PRESSURE BY DIET AND EXERCISE

better at reducing blood pressure (p=.02) over four months. Edwards et al. (2011), also found

significant benefit to lowering blood pressure from either exercise only or a joint exercise and

dietary approach blood pressure (p=.006). However, the study did not support a significant

benefit in performing multiple interventions at the same time (p=.053). Zia et al. (2013)

demonstrated significant reductions of blood pressure in both multiple intervention groups with

greater numbers of participants receiving the benefit that used the rice diet instead of the DASH

diet. Since clinical guidelines do not support using stress reduction techniques to lower chronic

blood pressures, it is reasonable to suppose a greater effect achieved from the drastic difference

in dieting, as there were similarities in exercise. From blood pressure clinical guidelines of the

Emergency Care Research Institute (2013), it is proposed that exercise should be performed as an

every-other-day routine for a minimum of 30-45 minutes. These guidelines confirm high

potassium diets, supports unsaturated fat intake, and does not support emphasizing stress

reduction.

Research supports that either exercise or heart-healthy dietary changes are effective to

lower blood pressure. However, in regards to safety, effective implementation, and sustainability,

one definite choice of dieting is not currently supported the evidence. Multiple interventions

performed at the same time may not be easily generalizable to clinical practice, as it is difficult to

duplicate the more highly motivated persons that are innately more likely to enroll in a study

aimed at lowering blood pressure. More research is needed for which diet is the most effective at

lowering blood pressure safely and sustainably for patients of various clinical venues. The rice

diet, although more effective than DASH diet principles at lower blood pressure in patients

already taking antihypertensive medications, probably should not be followed strictly due to

requiring supplementation to achieve recommended daily values. Supplements are shown to be

DECREASING BLOOD PRESSURE BY DIET AND EXERCISE

10

not as effective in achieving desired benefits (Huether & McCance, 2012).

Clinical Recommendations

The guidelines and studies demonstrate that both exercise and diet are effective

approaches to lowering blood pressure. Further developments should be done to determine what

exercise and what dietary approaches are most effective in lowering blood pressure safely, and

should be based upon past dietary history and overall clinical picture. Sustainability of these

methods as practical applications must be further researched and adapted to suit a wide variety of

communities with varying access to resources. Hypertension remodels vascularity and alters

perfusion over time, so it will take extended intervention time to achieve reduction of risk

through targeting blood pressure by diet and/or exercise. Teaching a patient with the family to be

more mindful of exercise and diet can easily spur a person to start performing research on the

internet to make different choices in either diet or exercise, whichever a person instinctively

favors. If multiple interventions are performed that would involve extreme weight loss, then the

plan should have professional guidance.

DECREASING BLOOD PRESSURE BY DIET AND EXERCISE

11

References

Blumenthal, J., Babyak, M., Hinderliter, A., Watkins, L., Craighead, L., Lin, P., ...

Sherwood, A. (2010). Effects of the DASH diet alone and in combination with exercise

and weight loss on blood pressure and cardiovascular biomarkers in men and women

with high blood pressure: The ENCORE study. Archives of Internal Medicine, 170(2),

126-135. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2009.470

Edwards, K. M., Wilson, K. L., Sadja, J., Ziegler, M. G., & Mills, P. J. (2011). Effects on blood

pressure and autonomic nervous system function of a 12-week exercise or exercise plus

DASH-diet intervention in individuals with elevated blood pressure. Acta Physiologica,

203(3), 343350. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.2011.02329.x

Emergency Care Research Institute (2013). Clinical practice guidelines on arterial hypertension.

Retrieved from http://www.guideline.gov/content.aspx?id=15712

Huether, S.E., & McCance, K.L. (2012). Understanding Pathophysiology (5th ed.). St. Louis,

MO: Elsevier Mosby.

Osborn, K., Wraa, C., Watson, A., Holleran, R. (Eds.). (2014). Medical-surgical nursing:

preparation for practice (2nd ed.). Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Pearson.

Ziv, A., Vogel, O., Keret, D., Pintov, S., Bodenstein, E., Wolkomir, K., Efrati, S. (2013).

Comprehensive approach to lower blood pressure: A randomized controlled trial of a

multifactorial lifestyle intervention. Journal of Human Hypertension, 27(10), 594600.

doi: 10.1038/jhh.2013.29

You might also like

- Pediatric Nursing Process Worksheet: USF College of Nursing: NUR 4467LDocument4 pagesPediatric Nursing Process Worksheet: USF College of Nursing: NUR 4467Lapi-324566318No ratings yet

- Picu WorksheetDocument7 pagesPicu Worksheetapi-324566318No ratings yet

- Nicu Worksheet CompletedDocument3 pagesNicu Worksheet Completedapi-324566318No ratings yet

- Portfolio-Goals PaperDocument2 pagesPortfolio-Goals Paperapi-324566318No ratings yet

- Pat 2 - Semester 2Document27 pagesPat 2 - Semester 2api-324566318No ratings yet

- Pat 1 Semester 2 TGH SBN Hekkanen ShawnDocument23 pagesPat 1 Semester 2 TGH SBN Hekkanen Shawnapi-324566318No ratings yet

- Pediatric Nursing Process Worksheet: USF College of Nursing: NUR 4467LDocument4 pagesPediatric Nursing Process Worksheet: USF College of Nursing: NUR 4467Lapi-324566318No ratings yet

- Final Draft Discussion Board 3-EthicsDocument3 pagesFinal Draft Discussion Board 3-Ethicsapi-324566318No ratings yet

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- General Information About High Blood PressureDocument4 pagesGeneral Information About High Blood PressureSusanne Seynaeve100% (1)

- Final Test SMT Vi 2021-2022Document3 pagesFinal Test SMT Vi 2021-2022Rihsan AlbahriNo ratings yet

- Design and Development of A Blood Pressure MonitorDocument34 pagesDesign and Development of A Blood Pressure Monitormihirshete100% (1)

- Pex 05 04Document4 pagesPex 05 04Wijoyo KusumoNo ratings yet

- Arterial LinesDocument38 pagesArterial LinesRabeed MohammedNo ratings yet

- Haemorrhage & ShockDocument22 pagesHaemorrhage & ShockAmiNo ratings yet

- Physiology Question BankDocument9 pagesPhysiology Question BankShriyaNo ratings yet

- Skin, Anaesthesia, Radiology and PsychiatryDocument209 pagesSkin, Anaesthesia, Radiology and PsychiatryDrChauhanNo ratings yet

- NCPDocument2 pagesNCPdimple caspilloNo ratings yet

- The Role of Adult Attachment Style in Forgiveness Following An Interpersonal OffenseDocument10 pagesThe Role of Adult Attachment Style in Forgiveness Following An Interpersonal OffenseEsterNo ratings yet

- Anesthesia PresentationDocument19 pagesAnesthesia PresentationJohnyNo ratings yet

- Manuskrip: Oleh: Dias Syaima Husniyah NIM. 1501009Document12 pagesManuskrip: Oleh: Dias Syaima Husniyah NIM. 1501009elsaNo ratings yet

- n378.008 Iris Website Staging of CKD PDFDocument8 pagesn378.008 Iris Website Staging of CKD PDFrutebeufNo ratings yet

- Hemodynamic MonitoringDocument37 pagesHemodynamic Monitoringsweet fairyNo ratings yet

- CopdDocument74 pagesCopdSardor AnorboevNo ratings yet

- Cholera Case StudyDocument44 pagesCholera Case StudyKrisianne Mae Lorenzo Francisco100% (3)

- MRCS Revision Guide Trunk and Thorax by Mazyar Kanani Leanne Harling (Z-LiDocument184 pagesMRCS Revision Guide Trunk and Thorax by Mazyar Kanani Leanne Harling (Z-LiRahmaNo ratings yet

- Invasive Arterial Blood PressureDocument31 pagesInvasive Arterial Blood PressureYanti PandianganNo ratings yet

- Case Study 2 PuneetDocument43 pagesCase Study 2 Puneetpuneetkaur6411No ratings yet

- Thrombolytic TherapyDocument24 pagesThrombolytic TherapyJayarani Ashok100% (1)

- VascularDocument40 pagesVascularOmar MohammedNo ratings yet

- Scorpion Envenomation: Review ArticleDocument7 pagesScorpion Envenomation: Review ArticleHugo Robles GómezNo ratings yet

- Bland Altman Measuring Comparison StudiesDocument27 pagesBland Altman Measuring Comparison StudiesirdinamarchsyaNo ratings yet

- Cool Spinal BathDocument11 pagesCool Spinal BathPrajwal G GowdaNo ratings yet

- Citricare 506DN ManualDocument100 pagesCitricare 506DN Manualmaria jose rodriguez lopezNo ratings yet

- NCD High-Risk Assessment (Community Case Finding Form) NCD High-Risk Assessment (Community Case Finding Form)Document1 pageNCD High-Risk Assessment (Community Case Finding Form) NCD High-Risk Assessment (Community Case Finding Form)Claribel Domingo BayaniNo ratings yet

- Jas AssignmentDocument3 pagesJas AssignmentjasperNo ratings yet

- Chest 2007 Marik 1949 62 (1) Hypertensive CrisisDocument16 pagesChest 2007 Marik 1949 62 (1) Hypertensive CrisisLaura LinaresNo ratings yet

- Pews Charts 4 11 MonthsDocument2 pagesPews Charts 4 11 MonthsKiara RevalinaNo ratings yet

- Sample Chapter of Assessment Made Incredibly Easy! 1st UK EditionDocument28 pagesSample Chapter of Assessment Made Incredibly Easy! 1st UK EditionLippincott Williams and Wilkins- Europe100% (1)