Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Mortensene Populationatrisknurs340

Uploaded by

api-284786443Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Mortensene Populationatrisknurs340

Uploaded by

api-284786443Copyright:

Available Formats

Running head: POPULATION AT RISK

Population at Risk

Emily Mortensen

Ferris State University

POPULATION AT RISK

Population at Risk

When a puzzle box has first been opened, at first glance, a persons reaction may be

woeful. This individual may react negatively to the disarray, and consider giving up the

challenge of solving the problem before they even begin. As they go through the process of

completing the puzzle, they find the beauty in the process, how each piece works with the others

in order to form a complete image. The world is full of puzzles, or pieces coming together to

complete the whole. One puzzle in this world is a persons health. A persons health is made up

of numerous items, including their genetic makeup, and how they care for themselves, among

many other items. One item that has a large influence somebodys health is the population that

they belong to. The population somebody is associated with can determine their risk for health

disparities. A population that is commonly associated with this increased risk is incarcerated

women.

Throughout history, America has been presented as a patriarchal society, with

more attention given to the male citizens. This discrepancy is strongly presented in the criminal

justice system. The system that is in place today has been created for men, ignoring the special

needs of women who have found themselves in a home behind bars (Braithwaite, Treadwell, &

Arriola, 2005).

Historically, women in prison have not been presented ideal living conditions. Before the

first all-female prisons were created, these women were placed in a unit of the mens prisons.

These prisons treated their female inhabitants poorly, with punishment of solitary confinement

over utilized, and these women were regularly victims of physical or sexual abuse by the male

inmates and the male guards. In 1825, a pregnant woman named Rachel Welch passed away

because she was beaten while imprisoned by a male guard. After this event, changes were made

to the housing situations of imprisoned women, and the first all-female facility, The Mount

Pleasant Prison Annex, was opened in 1839. This facility was imperfect, while it did have a

POPULATION AT RISK

female warden, it was on the grounds of Sing Sing, an all-male institution, and both facilities

were under male control. These administrators were unaware of what exactly incarcerated

women required. Even with these attempts to eliminate the abuse of these women, the women at

this new facility still fell victim to high levels of abuse and corporal punishment (Mallicoat,

2014).

In the United States today, there are over 205,000 women imprisoned, a number that

increased by an alarming 646% between the tears of 1980 and 2010 (Sentencing Project, 2012).

In the year 2013, there were 14,169 women in federal prisons, and Michigan jails housed 2,059

female inmates (Carson, 2014). Black or Hispanic women are at a greater risk for becoming

imprisoned than Caucasian women. While the likelihood for imprisonment for white women in

2001 was one in 118, for Hispanic women, the likelihood was one in 45, and for black women,

the number rose to one out of every 19 women (Sentencing Project, 2012).

Stereotypes that are often presented with female inmates include that they are irrational,

emotional, and hard to control. These biases cause these individuals to be brushed off, and not

taken seriously. The separation that prisoners experience from society is another source of bias.

Since these individuals are seen as separate from other United States citizens, and they have

committed crimes, they are seen as less than human. Individuals are more willing to treat others

poorly when they see themselves as more than the other person, as presented in the Stanford

prison experiment, where participants were randomly assigned the role of either prisoner or

guard. The guards began to treat the prisoners cruelly and became extremely controlling of them,

even though when they walked into the study, these individuals were all equals (Haney, 2007).

In the United States criminal justice system, incarcerated women receive substandard

health care in comparison to males, which has a damaging effect on these women. A NCCD

study in 1996 interviewed 151 female inmates, which found that 61% of these women required

treatment for a physical problem, and 455 required treatment for their mental health. As

POPULATION AT RISK

compared to men, these women required more medical assistance for their health problems, but

had lesser access to the care that they needed (Acoca, 1998).

If medical care did become available, it was implemented poorly, with inadequate

supervision and follow-up to the care to ensure that it worked effectively. With this flaw in the

system, prisoners with chronic diseases began to deteriorate and lose quality of life faster than

they would have if they had received adequate care. The prisoners receiving mental health

medications became overmedicated and suffered the effects of these chemical restraints (Acoca,

1998).

In this population of incarcerated women, their health concerns are an issue that needs to

be addressed, and the care of these issues needs to be improved greatly. These women are at an

increased risk for HIV infection, along with other sexually transmitted infections, infectious and

communicable diseases, mental health disorders, and reproductive health problems. One

explanation for why these inmates receive such poor health care is because their doctors do not

take their health concerns seriously. It has been found that male doctors . . . often attribute

womens complaints to psychosomatic causes (Acoca, 1998, par.8). It is because of this bias

that health care providers are not giving these patients the medical attention that they need, and

many illnesses are going undiagnosed or untreated among these women.

One of the most prevalent health issues that incarcerated women face is substance abuse.

In the 1996 NCCD study, over 80% of the interviewed women had reported a history of regular

drug or alcohol use, and 71% reported that they had used it regularly within a month of their

arrest. This problem is addressed poorly in correctional facilities, with two-thirds of women

stating that the treatment they require for their substance abuse was not available to them (Acoca,

1998).

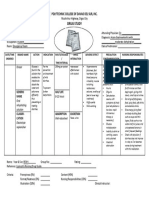

Villagr Lanza, Fernndez Garca, Rodguez Lemelas, & Gonzlez-Menndez conducted

a randomized controlled study to compare different treatment methods for substance abuse

POPULATION AT RISK

disorder. There were 50 incarcerated women participating in the trial. They had to meet the

diagnostic criteria for substance abuse disorder and were required to be serving a sentence of

greater than six months in length (see Appendix A for participants characteristics). The two

treatment methods that were utilized in this treatment were acceptance and commitment therapy

(ACT) and cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), and there was a control group present as well

(2014).

The patients that were involved in the CBT treatment worked to identify the thoughts that

were causing the patients to desire the drugs, and worked to alter their behavior to limit these

situations, or their reactions to them. The ACT treatment worked to help the patients to respond

in a better way to previously avoided events. It was proven that for long-term success of

treatment, ACT proved to be more effective than CBT in reducing drug use (43.8% versus

26.7%, respectively) and improving mental health (26.4% versus 19.4%, respectively) of

incarcerated women (Villagr Lanza, Fernndez Garca, Rodguez Lemelas, & GonzlezMenndez, 2014).

For nursing purposes, there are different therapeutic strategies that could be implemented

to aid the prisons in improving the care of incarcerated women who are dependent on substances.

The first strategy is to establish a trusting relationship between the patient and the caregiver. This

strategy helps the patient to feel more accepted, and they are more willing to comply with the

care plan when they have that relationship with their caregiver. Accompanying the trusting

relationship with the staff, it is essential that these clients also form trusting relationships with

their peers. This helps the clients to feel that they have support, and they will be more willing to

open up when they are among peers that they trust (Finfgeld-Connett & Johnson, 2011).

Individualized care is another technique that helps clients to find success in substance

treatment programs. Practitioners who have developed their critical thinking and problem solving

skills will be required in order to make decisions in treatment. When an individual is seeking

POPULATION AT RISK

treatment for an ailment, they are more willing to comply with the regimen if they feel that they

have not received a highly individualized plan that fits all of their needs and their exact situation

(Finfgeld-Connett & Johnson, 2011).

Separation from the general population of the prison is another technique that can help

the patients to find more success in their treatment programs. In the general environment of the

prison, women are told to be extremely independent. This technique is effective in keeping the

prisoners out of more trouble, but it is detrimental to the success at halting the use of an addictive

substance. This technique helps the patients to follow through on their individualized treatment

plans, and gives them ample opportunity to form relationships with their care providers and their

peers. The environment in these treatment programs is one of caring and support, and with this,

the clients are likely to remain successful in cessation of substance dependence upon completion

of the program (Finfgeld-Connett & Johnson, 2011).

A policy that affects the lives and care of all prisoners is the prisoners rights law. This

law outlines the rights that an inmate has while behind bars. One segment of the prisoners rights

law relates directly to medical and mental health care. This segment states that they are entitled

to care for these problems, but the treatments are only required to be adequate, as opposed to the

best available care or standard treatment available to the general population (HG Legal

Resources, 2015).

This policy has a negative effect on the population of incarcerated women, as well as

incarcerated men. The fact that these individuals are only receiving substandard treatment for

their medical ailments shows that they are not able to effectively fight these diseases, and

morbidity will be more prevalent in these communities. If an individual with diabetes is

incarcerated, she will be more likely to remain uncontrolled. With her uncontrolled diabetes, this

individual will have a heightened risk at contracting the complications of cardiovascular disease,

neuropathy, kidney, eye, food, damage, hearing impairment, skin conditions, and Alzheimers

POPULATION AT RISK

disease (Mayo Clinic, 2015). These individuals are more likely to die at a younger age due to the

ineffective treatment that they are receiving.

The population of incarcerated women is one that is at risk for a number of problems.

They are subjected to abuse, and are at a greater risk for HIV and other sexually transmitted

diseases, communicable and infectious disease, mental health disorders, reproductive health

problems, and substance abuse. These women are not entitled to receive proper care for any

illnesses that they have, and have increased morbidity because of that. The fact that these women

are incarcerated is one piece to the puzzle of their individual health, and each woman is a piece

to the puzzle of a highly flawed system for providing care to these women. Significant changes

will be required for the United States justice system to ensure that these women receive the care

that they need in order to live long and healthy lives.

POPULATION AT RISK

References

Acoca, L. (1998). Defusing the time bomb: Understanding and meeting the growing health care

needs of incarcerated women in America. Crime and Delinquency, 44(1), p. 49.

Braithwaite, R. L., Treadwell, H. M., and Arriola, K. R. J. (2005). Health disparities and

incarcerated women: A population ignored. American Journal of Public Health, 95(10),

p. 1679-1681. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.065375

Carson, E. A. (2014). Prisoners in 2013. Retrieved from http://www.bjs.gov/

Finfgeld-Connett, D., and Johnson, E. D. (2011). Therapeutic substance abuse treatment for

incarcerated women. Clinical Nursing Research, 20(4) p. 462-481. doi:

10.1177/1054773811415844

Haney, C. (2007). Stanford Prison Experiment. In Y. Jewkes & J. Bennett (Eds.), Dictionary of

prisons and punishment. Devon, United Kingdom: Willan Publishing.

HG Legal Resources (2015). Prisoners Rights Law. Retrieved from http://www.hg.org/prisonerrights-law.html

Mallicoat, S. L. (2014) Women and crime: A text/reader (2nd ed.). United States: SAGE

Publications

Mayo Clinic (2015). Type 2 diabetes. Retrieved from http://www.mayoclinic.org/

Sentencing Project, The (2012). Incarcerated women. Retrieved from

http://www.sentencingproject.org/doc/publications/cc_Incarcerated_Women_Factsheet_D

ec2012final.pdf

Villagr Lanza, P., Fernndez Garca, P., Rodguez Lemelas, F. & Gonzlez-Menndez, A.

(2014). Acceptance and commitment therapy versus cognitive behavioral therapy in the

treatment of substance use disorder with incarcerated women. Journal of Clinical

Psychology, 70 (7), p. 644-657. doi: 10.1002/jclp.22060

POPULATION AT RISK

9

Appendix A

M(SD)

M

M(SD)

SD)

(6.4)

33.1

(5.8)

(mos.)

50

(33.1)

38.7

59.1

(37.7)

of

(9.4)

drug

16.7

abuse

(5.7)

19.9

14.8

(2.2)

(yrs.)

7.9

(6.1)

11.3

12.6

(9.2)

(6.5)

variable

n(%)

n(%)

Marital

n(%)

13

(72.2%)

7(20.1)

(53.8%)

1

(7.7%)

4

(22.2%)

Widow

Criminal

1status

typology

(5.3%)

public

health

(50%)

(30.8%)

(27.8%)

44

(44.4%)

9

(50%)

(61.5%)

persons

(22.2%)

(5.6%)

(7.7%)

Main

substance

9

(50%)

8

(61.5%)

5

(38.5%)

(27.8%)

5

Alcohol

31

(16.7%)

1

(5.6%)

(5.3%)

SD

deviation;

=

standard

CBT

=(8

behavioral

cognitiveacceptance

ACT

and

=

therapy;

CG

=9

control

group.

condition

CBT

ACT

CG

Characteristics

Table

15

(Villagr Lanza, Fernndez Garca, Rodguez Lemelas, & Gonzlez-Menndez, 2014).

You might also like

- Nclex Past QuestionsDocument452 pagesNclex Past Questionsjyka100% (21)

- Bariatric SurgeryDocument252 pagesBariatric SurgeryEdward-Dan Buzoianu100% (2)

- Sprint-8 Intervals: Turn On Your Afterburners!: Directions: For "Optimal" Results, Follow These Simple GuidelinesDocument1 pageSprint-8 Intervals: Turn On Your Afterburners!: Directions: For "Optimal" Results, Follow These Simple Guidelinesknowman1No ratings yet

- Summary of ECG AbnormalitiesDocument8 pagesSummary of ECG AbnormalitiesChristine Nancy NgNo ratings yet

- Code of Ethics For NursesDocument5 pagesCode of Ethics For NursesKamran Khan100% (1)

- Angels in The NurseryDocument17 pagesAngels in The NurseryRoxana DincaNo ratings yet

- Cheilitis 2Document10 pagesCheilitis 2pelangiNo ratings yet

- Application of CTASDocument32 pagesApplication of CTASsidekick941No ratings yet

- Scholarly Paper-CrumplerDocument8 pagesScholarly Paper-Crumplerapi-354214139No ratings yet

- Running Head: Annotated Bibliography Tomkins 1Document9 pagesRunning Head: Annotated Bibliography Tomkins 1api-303232478No ratings yet

- Scholarly FinalDocument13 pagesScholarly Finalapi-284372198No ratings yet

- Services in Prison For Victims of Abuse: Issues and Options: Annie Bartlett ST George's University of LondonDocument26 pagesServices in Prison For Victims of Abuse: Issues and Options: Annie Bartlett ST George's University of LondondjjaomafiaNo ratings yet

- Population Risk Paper - 2Document8 pagesPopulation Risk Paper - 2api-301802746No ratings yet

- Literacy and Perceived Barriers To Medication Taking - Full TextDocument6 pagesLiteracy and Perceived Barriers To Medication Taking - Full TextDana ChilelliNo ratings yet

- Scholarly PaperDocument6 pagesScholarly Paperapi-430368919No ratings yet

- Mental Health FacilitiesDocument11 pagesMental Health FacilitiesMiKayla PenningsNo ratings yet

- Nurs 340 Vulnerable Population PaperDocument6 pagesNurs 340 Vulnerable Population Paperapi-240550685No ratings yet

- Vulnerable Population ProjectDocument6 pagesVulnerable Population Projectapi-739007989No ratings yet

- V 32 N 2 A 3Document9 pagesV 32 N 2 A 3sofia_rangel_16No ratings yet

- Research Proposal Katherine ZamoraDocument6 pagesResearch Proposal Katherine Zamoraapi-310067380No ratings yet

- UT Texas Policy Evaluation ProjectDocument5 pagesUT Texas Policy Evaluation ProjectMarkAReaganNo ratings yet

- U10a1 ProjectDocument18 pagesU10a1 Projectapi-256660439No ratings yet

- DIABETESDocument11 pagesDIABETESSophia Gayle RaagasNo ratings yet

- SynopsisDocument3 pagesSynopsisapi-301826049No ratings yet

- Self-Induction of Abortion Among Women in The United StatesDocument11 pagesSelf-Induction of Abortion Among Women in The United StatesNurcahyo Tri UtomoNo ratings yet

- Research EssayDocument11 pagesResearch Essayapi-519864021No ratings yet

- Ananotaed BibliographyDocument12 pagesAnanotaed BibliographyElvis Rodgers DenisNo ratings yet

- L Vasqueznurs340vulnerablepopulationDocument6 pagesL Vasqueznurs340vulnerablepopulationapi-240028260No ratings yet

- Maternal Nursing Care - CHPT 6 Human Sexuality and FertilityDocument28 pagesMaternal Nursing Care - CHPT 6 Human Sexuality and Fertilitythubtendrolma100% (1)

- Summary - CHCF Report On Dual DiagnosisDocument2 pagesSummary - CHCF Report On Dual DiagnosisShakari ByerlyNo ratings yet

- Senior FinalDocument23 pagesSenior Finalapi-350348558No ratings yet

- Running Head: Racism in Healthcare 1Document9 pagesRunning Head: Racism in Healthcare 1api-307925878No ratings yet

- Order ID 367572818Document6 pagesOrder ID 367572818Sebastian MauricNo ratings yet

- Gender Differences Among Prisoners in Drug TreatmentDocument22 pagesGender Differences Among Prisoners in Drug TreatmentlosangelesNo ratings yet

- Lehal 540 LitReviewDocument11 pagesLehal 540 LitReviewlehalnavNo ratings yet

- Running Head: Serious Mental Illness in The Correction System 1Document11 pagesRunning Head: Serious Mental Illness in The Correction System 1api-247059278No ratings yet

- NSG 106Document12 pagesNSG 106Anipah AmintaoNo ratings yet

- Tholmes Research PaperDocument9 pagesTholmes Research Paperapi-437977619No ratings yet

- Ruiz 2013Document15 pagesRuiz 2013Álex SGNo ratings yet

- Aa PortfolioDocument4 pagesAa Portfolioapi-302570922No ratings yet

- Women in Prison: Approaches in The Treatment of Our Most Invisible PopulationDocument12 pagesWomen in Prison: Approaches in The Treatment of Our Most Invisible PopulationRabab AbbasNo ratings yet

- Transgender Surgery Isn't The Solution: © 2014 Courage International, IncDocument2 pagesTransgender Surgery Isn't The Solution: © 2014 Courage International, Incda5idnzNo ratings yet

- Evaluation of A Comedy Intervention To Improve Coping and Help-Seeking For Mental Health Problems in A Women ' S PrisonDocument8 pagesEvaluation of A Comedy Intervention To Improve Coping and Help-Seeking For Mental Health Problems in A Women ' S PrisonGINA ZEINNo ratings yet

- Welfare Mental HealthDocument19 pagesWelfare Mental HealthyomamaisfrhereNo ratings yet

- Womens Health Research Paper TopicsDocument5 pagesWomens Health Research Paper Topicsaflbrozzi100% (1)

- Final Chep 1Document5 pagesFinal Chep 1api-578023155No ratings yet

- Activity 3: Background StudyDocument11 pagesActivity 3: Background StudyCharlotte MartinNo ratings yet

- The Prevalence of Domestic Violence Among Women Seeking AbortionDocument5 pagesThe Prevalence of Domestic Violence Among Women Seeking Abortionjelly mutyaraNo ratings yet

- HNR 3700 - Community Perceptions of Prison Health Care Final ProposalDocument18 pagesHNR 3700 - Community Perceptions of Prison Health Care Final Proposalapi-582630906No ratings yet

- Inequidades de Género, Abuso de Sustancias y Barreras Al Tratamiento en Mujeres en PrisiónDocument8 pagesInequidades de Género, Abuso de Sustancias y Barreras Al Tratamiento en Mujeres en PrisiónDaniel Gonzales FielNo ratings yet

- Manuscript PDFDocument20 pagesManuscript PDFHasan MahmoodNo ratings yet

- The in Uence of Child Abuse On The Pattern of Expenditures in Women's Adult Health Service Utilization in Ontario, CanadaDocument9 pagesThe in Uence of Child Abuse On The Pattern of Expenditures in Women's Adult Health Service Utilization in Ontario, CanadaPriss SaezNo ratings yet

- Best Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics and GynaecologyDocument12 pagesBest Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics and GynaecologyCristina ToaderNo ratings yet

- Miss Evers BoysDocument4 pagesMiss Evers Boysarij 20100% (4)

- Peer Victimization PaperDocument21 pagesPeer Victimization Paperapi-249176612No ratings yet

- Thesis Proposal-Gratitude of Recovering Drug AddictsDocument12 pagesThesis Proposal-Gratitude of Recovering Drug AddictsMA. ALNIKKA GIMENA PONTERASNo ratings yet

- Capstone Final Paper MasterDocument24 pagesCapstone Final Paper Masterapi-667931371No ratings yet

- HomelessDocument8 pagesHomelessapi-520141947No ratings yet

- Vuln Pop PaperDocument7 pagesVuln Pop Paperapi-428103455No ratings yet

- Lit Review2Document10 pagesLit Review2api-341202764No ratings yet

- Nietes 2b Cta5Document3 pagesNietes 2b Cta5HALLEBERRY G. NIETESNo ratings yet

- Do Rituals Violate The Rights of The Mentally Ill Patient?: G.S.S.R. Dias & Induwara GooneratneDocument3 pagesDo Rituals Violate The Rights of The Mentally Ill Patient?: G.S.S.R. Dias & Induwara Gooneratnetracker1234No ratings yet

- Prescription Medication Borrowing and Sharing Among Women of Reproductive AgeDocument8 pagesPrescription Medication Borrowing and Sharing Among Women of Reproductive AgeWulan CerankNo ratings yet

- Utilización de Servicios de Atención A La Salud Mental en Mujeres Víctimas de Violencia ConyugalDocument7 pagesUtilización de Servicios de Atención A La Salud Mental en Mujeres Víctimas de Violencia ConyugalErika JohanaNo ratings yet

- SM Mujeres ViolenciasDocument7 pagesSM Mujeres ViolenciasAngélica GonzálezNo ratings yet

- Research Papers On Prescription Drug AbuseDocument6 pagesResearch Papers On Prescription Drug Abusejsmyxkvkg100% (1)

- KolcabaDocument7 pagesKolcabaapi-284786443No ratings yet

- Mortensene Issueanalysispaper Nurs450Document18 pagesMortensene Issueanalysispaper Nurs450api-284786443No ratings yet

- Mortensene Newbornassessmentnurs341Document8 pagesMortensene Newbornassessmentnurs341api-284786443No ratings yet

- Mortensene Researchpresentationnurs441Document12 pagesMortensene Researchpresentationnurs441api-284786443No ratings yet

- Service Learning ProjectDocument14 pagesService Learning Projectapi-284786443No ratings yet

- Philippines Grouppresentation Supernurses Nurs250Document21 pagesPhilippines Grouppresentation Supernurses Nurs250api-284786443No ratings yet

- Nurs 440 Ana Selfassessment Template 2 1Document7 pagesNurs 440 Ana Selfassessment Template 2 1api-284786443No ratings yet

- Running Head: PATIENT FALLS 1Document9 pagesRunning Head: PATIENT FALLS 1api-284786443No ratings yet

- Mortensene Ebpbrochurenurs300Document2 pagesMortensene Ebpbrochurenurs300api-284786443No ratings yet

- Mortensene RiskreductionDocument11 pagesMortensene Riskreductionapi-284786443No ratings yet

- Mortensene ApasafetyqualityDocument5 pagesMortensene Apasafetyqualityapi-284786443No ratings yet

- Skin Diseases of GoatsDocument8 pagesSkin Diseases of GoatsmadheshvetNo ratings yet

- How Can Holistic Health Benefit MeDocument2 pagesHow Can Holistic Health Benefit Meanna ticaNo ratings yet

- Induction of LabourDocument51 pagesInduction of LabourvaleriaNo ratings yet

- DR Halit Ibrahimi - Social Withdrawal and Bizarre Behavior in An 18 Years Old ManDocument11 pagesDR Halit Ibrahimi - Social Withdrawal and Bizarre Behavior in An 18 Years Old ManbardhoshNo ratings yet

- Get Big Diet by Jacob WilsonDocument5 pagesGet Big Diet by Jacob WilsonYoel OrueNo ratings yet

- Sasha Brattain - Weebly ResumeDocument3 pagesSasha Brattain - Weebly Resumeapi-451586061No ratings yet

- Chapter 12 Ears Nose Mouth and ThroatDocument3 pagesChapter 12 Ears Nose Mouth and ThroatKhanh HoangNo ratings yet

- Storage of Cellular Therapy Products Presentation Slide Format PDFDocument61 pagesStorage of Cellular Therapy Products Presentation Slide Format PDFpopatlilo2100% (1)

- Ds OresolDocument1 pageDs OresolShannie Padilla100% (1)

- Rebekah Wilson PT ResumeDocument3 pagesRebekah Wilson PT Resumeapi-487211279No ratings yet

- Sweet Crystals TBDocument4 pagesSweet Crystals TBCristine Joy Jimenez SavellanoNo ratings yet

- Pulmonary TuberculosisDocument68 pagesPulmonary TuberculosisNur Arthirah Raden67% (3)

- Newborn ResuscitationDocument34 pagesNewborn ResuscitationNishaThakuri100% (2)

- 2014 CCM Review Notes Jon-Emile S. Kenny M.D, 2014Document142 pages2014 CCM Review Notes Jon-Emile S. Kenny M.D, 2014PkernNo ratings yet

- Nutrition and Aging P.110: - Risk For Malnutrition or OvernutritionDocument21 pagesNutrition and Aging P.110: - Risk For Malnutrition or OvernutritionChester NicoleNo ratings yet

- Neuropathic Pain Scott GroenDocument77 pagesNeuropathic Pain Scott GroenFabrienneNo ratings yet

- GorakhamundiDocument2 pagesGorakhamundiGirish SahareNo ratings yet

- The Psychological AspectsDocument7 pagesThe Psychological AspectsInvisible_TouchNo ratings yet

- Ketorolac and NalbuphineDocument4 pagesKetorolac and NalbuphineMaureen Campos-PineraNo ratings yet

- LIST OF REGISTERED DRUGS As of December 2012: DR No Generic Name Brand Name Strength Form CompanyDocument84 pagesLIST OF REGISTERED DRUGS As of December 2012: DR No Generic Name Brand Name Strength Form CompanyBenjamin TantiansuNo ratings yet

- Acrylic Removable Partial Denture & Impression Techniques in Complete DentureDocument9 pagesAcrylic Removable Partial Denture & Impression Techniques in Complete DentureMohammed ZiaNo ratings yet

- Lupus NephritisDocument15 pagesLupus NephritisVilza maharaniNo ratings yet

- Flow Trac SystemDocument4 pagesFlow Trac Systempolar571No ratings yet