Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Module A: Definition, Context and Knowledge of School Violence Unit A1: Understanding The Definition and Context of School Violence

Uploaded by

John2jOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Module A: Definition, Context and Knowledge of School Violence Unit A1: Understanding The Definition and Context of School Violence

Uploaded by

John2jCopyright:

Available Formats

VISTA Unit A1: Understanding the definition and context of school violence

Module A: Definition, Context and Knowledge of School

Violence

Unit A1: Understanding the Definition and Context of School

Violence

Rosario Ortega1, Virginia Sanchez1,

Luc Van Wassenhoven2, Gie Deboutte2 and Johan Deklerck2

1

Spain

2

Belgium

Objectives of Unit A1

To be aware of a range of interpretations of school violence

To be able to consider the key factors involved in a definition of school

violence from a variety of perspectives

To understand the social and cultural contexts where school violence

takes place

To interpret violent behaviour within a complex social system

To evaluate and integrate different theoretical perspectives of school

violence

Facilitation skills to be developed through this Unit

Knowledge and understanding of:

current thinking about definitions of school violence

the relationships between social context and school violence

the links between school climate and school violence

the importance of creating a supportive and caring school community

Personal qualities and attributes include:

being able to adopt a critical and reflective stance in the analysis of

complex social phenomena

being able to reflect on others ideas through open debate

being able to integrate different theoretical perspectives on school

violence

Pre-unit reading

Council of Europe. (2002). Violence in schools A challenge for the local

community. Strasbourg: Council of Europe Publications.

http://www.coe.int/t/e/integrated_projects/violence/06_Our_publications/Viol

ence%20in%20schools%20a%20challenge%20for%20the%20local%20com

munity.pdf

Smith, P. K. (2003). Violence in schools: An overview. In P. K. Smith (Ed.),

Violence in schools. The response in Europe (pp. 1-14). London:

RoutledgeFalmer,

Vettenburg, N. (1999). Violence in schools: Awareness-raising, prevention,

penalties. General Report. Luxembourg: Council of Europe Publications.

VISTA Unit A1: Understanding the definition and context of school violence

World Health Organization (WHO). (2002). Violence - a global public health

problem. Chapter 1, pp. 3-21, World Report on Violence and Health.

Geneva: Author.

http://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/violence/world_report/en/inde

x.html

Summary of current thinking and knowledge about the definition

and context of school violence

Definitions of school violence

What is school violence? In general, the definition can cover the following

categories: verbal, physical, sexual and psychological violence; social exclusion;

violence relating to property; violence relating to theft; threats; insults; rumourspreading (Smith, Morita, Junger-Tas, Olweus, Catalano, & Slee, 1999; Smith,

2003). Olweus (1999, p.12) defines it as aggressive behaviour where the actor

or perpetrator uses his or her own body or an object (including a weapon) to

inflict (relatively serious) injury or discomfort upon another individual. Definitions

which go beyond physical harm include the one given by the World Health

Organization (WHO, 2002) which includes threats as well as actual violence,

while Debarbieux (2003) identifies ideological and historical influences on the

ways in which a society chooses to define the phenomenon of violence. As he

writes:

What we call violence is ideologically and historically determined. Our current

concern about violence in education also reflects our changing relationship to

violence. From being accepted, if not actually encouraged, it has become

intolerable to us in Europe. This is not a universal phenomenon but it is an

indication of a new shared vision of childhood. This vision oscillates between the

continuing notion of totally uncivilised children requiring a form of orthopaedic

[sic] correction and the consequences of what in 1900 the Swedish educationalist

Ellen Key called the century of the child, with affection preferred to restraint, and

prevention to punishment (Debarbieux, 2003, pp. 43-44).

In her report to the Council of Europe, Vettenburg (1999) concluded that there

was no clear definition of school violence, which made it difficult, amongst other

things, to ascertain whether school violence was on the increase or to make valid

comparisons between different countries rates of school violence. However, as

Debarbieux (2003) points out, there is now greater awareness of the need to

accept a multiplicity of definitions of school violence from a range of

perspectives, including those of children and young people. This enables

researchers and practitioners to build up a solid base of knowledge and to

accumulate hypotheses which can be retained or discarded in the light of

research findings as they emerge.

The context of school violence

In order to be able to understand the complex phenomenon of school violence,

a comprehensive analysis of the economic, cultural, school and individual

VISTA Unit A1: Understanding the definition and context of school violence

context in which it is generated is necessary. The VISTA analysis adopts a

bio-ecological perspective (Bronfenbrenner, 1979; Bronfenbrenner & Morris,

1998). (See Figure 1).

Wider

Context

School Context

Interpersonal

Context

Individual

Figure 1. Bio-ecological model for understanding the prevention of school

violence (adapted from World Health Organization, 2002)

Most researchers in the field now take account of social-cultural factors, such

as race, gender and social class in their analysis of the problem. Risk and

protective factors relating to violence are found at each level in the model,

including the individual, the interpersonal, the school and the wider social

context. Risk factors are those factors that render an individual more likely to

develop problems in the face of adversity; they do not in themselves

necessarily cause difficulties. Protective factors are those factors that act to

protect an individual from developing a problem even in the face of adversity.

It is very hard to unravel specific causative factors since the interacting

variables are multiple but longitudinal research studies that follow childrens

development from an early age can identify those risk and protective factors

that appear in chains of causation, so offering an evidence base for the design

of interventions.

In order to understand why school violence occurs, VISTA recommends an open

and flexible approach rather than a simple cause-and-effect analysis. In the next

section, following Bronfenbrenners model, we explore ways in which different

contexts individual, interpersonal, school and the wider society - can either

promote or reduce the phenomenon of school violence (Farrington, 1998).

Individual context

Researchers have studied in depth the individual characteristics of boys and girls

who become aggressors, as well as those who become victims. Aggressive

boys and girls are impulsive, with low self control and low resistance to frustration

(Baldry & Farrington, 2000). In addition, several studies have shown that

aggressive children display important cognitive deficits relating to the

interpretation of social events, giving hostile attributions to ambiguous social

3

VISTA Unit A1: Understanding the definition and context of school violence

situations (Dodge & Frame, 1982). Recent research has also found that

differences with regard to social and cognitive skills between girls and boys, can

help us understand the gender differences found in children involved in violent

and criminal behaviour. Key social and cognitive skills seem to protect girls from

getting involved in these kinds of actions, compared to boys (Bennett, Farrington,

& Huesmann, 2004).

Theory of mind explains why some children bully their classmates (Smorti,

Ortega, & Ortega, 2002; Sutton, Smith, & Swettenham, 1999). Bullies seem to be

good cognitive strategists, able to sense the details of their actions and, in

consequence, are able to notice others pain, although with limited empathy

(Menesini, Snchez, Fonzi, Ortega, Costabile, & Lo Feudo, 2003). With regard to

victims, studies have shown that they tend to have low self esteem, are shy, and

have difficulty in making friends.

Interpersonal contexts

At the same time, violence must be considered in the context of interpersonal

relationships. For example, friends can be either a protective or a risk factor for

being victimized, depending on the quality of the friendship (Adams, Bukowski, &

Bagwell, 2005). Fundamentally, the nature of family relationships plays a critical

role in the development of peer relationships at school (Smith, Bowers, Binney, &

Cowie,1993). Farrington (1998) indicates three family factors linked to the risk of

engaging in school violence:

Absence of affection and emotional warmth between fathers and mothers and

in general in the family group which is apparent in the first years of school life.

Existence and use of physical or psychological violence in the family group;

living in a family setting where domestic violence is common.

Absence of rules, guidelines and reasonable controls, coming from adults,

about conduct, attitudes, childhood activities.

Regarding parenting styles, Baldry and Farrington (1998) found that boys who

bully tended to have authoritarian and punitive parents, whereas victims tended

to have authoritarian parents with low self-esteem. Other studies found a

relationship between mothers over-protectiveness and male victims; for female

victims, there was a significant relationship with perceived mother rejection

(Finnegan, Hodges, & Perry, 1998)

Attachment theory suggests that early on children develop an internal working

model of relationships which explains, for example, the victims psychological

defencelessness and the perpetrators unjustified aggression. Studies aimed at

exploring the relationships between bullying problems and attachment have also

found that insecure children are more likely to be involved in bully/victim

problems (Smith & Myron-Wilson, 1998), especially for being a victim of bullying.

Attachment theory can help to explain, for example, the high probability that

children from families where abuse occurs (between parents as well as from

parents to children) are likely to repeat the same insecure patterns in the

relationships they have with peers.

VISTA Unit A1: Understanding the definition and context of school violence

VISTA Unit A1: Understanding the definition and context of school violence

School context

Interpersonal relationships, grounded in the family, are further developed at

school. Violence flourishes in institutional environments, such as schools, in

which frequent contact among the participants can perpetuate stereotypical roles

of dominance and submission (Ortega, 1994). Stable contexts like schools have

the potential to create conditions that encourage positive relationships through

the process of convivencia, the action of living with others, with a spirit of

solidarity, fraternity, co-operation, harmony, a desire for mutual understanding,

the desire to get on well with others, and the resolution of conflict through

dialogue or other non-violent means (Ortega, del Rey, & Mora-Merchn, 2004,

p. 169). It is essential to know how the social networks that support convivencia

are established, as well as the counteracting forces that undermine convivencia.

No school is the same as another, just as no pupil is the same as another. Some

pupils lack motivation, or are bored at school, or resent rules and regulations;

some have difficult family backgrounds, or may be abused or bullied at home.

An important source of conflict between teachers and pupils involves the system

of discipline that the school adopts. In this sense, several programmes to

combat bullying and violence in schools emphasise the importance of discipline

systems for the containment of school violence (e.g., Olweus, 1999; OMoore &

Minton, 2004; Ortega, 2003; Ortega, del Rey, Snchez, Ortega-Rivera, MoraMerchn, & Genebat, 2003; Ortega & Lera, 2000; Smith, 1997)

Additionally, it is the social networks formed by pupils and teachers, and their

particular ways of behaving towards one another, that underpin convivencia.

Conflicts are an inevitable part of social life and schools are no exception.

Relationships amongst peers, and between teachers and pupils are a common

source of conflict in schools. Teachers often complain about the behaviour of

their pupils while not considering the impact that their own behaviour may have

on the school climate. However, there is no better way to create convivencia and

a non-violent culture than to face up to conflicts in an honest and problem-solving

way, whether they occur amongst the pupils or amongst the teaching staff.

Those conflicts must be resolved in a positive way since they provide pupils and

teachers with a source of real learning and of a chance to change.

Unresolved conflicts and unchallenged bullying behaviour can be selfperpetuating and so contaminate the processes of convivencia in the school.

The concept of convivencia allows us to explain the phenomenon of school

violence within the framework of interpersonal relationships that take place at

school. At the same time, the idea of convivencia can help us with the

prevention and reduction of school violence by harnessing those very

interpersonal processes that are embedded in the life of the school. If we grasp

this idea, we may not need to employ outside agencies to resolve the problem of

violence since the solution lies within the structures and networks of the school

itself.

VISTA Unit A1: Understanding the definition and context of school violence

The wider context

Sociologists and criminologists offer a wider perspective by charting the influence

that culture, society and politics exert on school violence. From this point of view,

school violence is regarded as a result of social pathology and social

vulnerability (Vettenburg, 1999; Walgrave, 1992) since there are certain sectors

of the population that are particularly at risk of engaging in violence. These

particular groups benefit less from the positive things institutions have to offer

(Vettenburg, 1999, p. 38) since too often they only confront the authority exerted

by society (as represented in this case by the school) but rarely experience the

benefits that society has to offer. They frequently have negative experiences

within the educational system (for example, learning difficulties, suspension and

exclusion, lack of respect from staff, under-achievement, low morale) which can

result in poor motivation, disaffection and a general sense of hostility towards the

school as a system.

Hargreaves (2003) underlines the impact of globalization on the educational

system and on the origins of violence. In capitalist societies, people tend to

behave in an individualistic, competitive way which perpetuates social class

differences and highlights the situation of disadvantaged groups. Potentially,

these cultural differences can have an impact on levels of violence in different

countries (Ortega et al., 2003). In fact, recent surveys have shown how

communities with a strong commitment to equality of opportunity have lower

levels of direct aggression (Bergeron & Schneider, 2005). It is all the more

important for the education system to promote the values of collaboration,

cooperation and creativity by actively working to develop a positive school culture

in schools.

Responsibilities of the Unit facilitators

Your tasks within this Unit are to:

send to all participants information about when and where the session will

be held and details of preparatory reading to be done

familiarise yourself with the Unit text and the facilitators notes

plan the session to meet the needs of the participants

ensure that all relevant resources/materials are copied and/or prepared

lead the session and all the activities

Sequence of activities for Unit A1

This Unit represents a one-day training of five hours plus breaks.

Activity 1 Icebreaker: The name game (15 minutes)

Purpose

To get to know everyones names

To begin to interact positively and purposefully with other members of the

group

Materials

None

7

VISTA Unit A1: Understanding the definition and context of school violence

Procedure

One person begins by saying their name. The person beside them then has to

say the first persons name and their own. The third person says the first and

second persons names and then their own. This goes on until everyone has

said their own name and all the others preceding them. The facilitator goes last

in order to show that taking the risk of not remembering a name is valued and

that it is all right to make mistakes.

Debriefing

The activity does not need debriefing but the facilitator can point out that some

people found it easier than others to remember names. However, the memory

process was also enabled through the co-operation, helpfulness, empathy and

support of the group. An additional benefit is often that people begin to help

others when they cannot remember the persons name and the process of

valuing individuals different strengths, so crucial to group cohesion, begins.

Activity 2 Introduce your neighbour (30 minutes)

Purpose

To begin to feel more comfortable in the group by interacting purposefully

with one member

To discover your own level of skill in questioning someone else and in

talking about yourself and in listening

To get everyone speaking in the large group, even those who would

normally avoid it

Materials

None

Procedure

Ask the participants to get into pairs, preferably with someone they do not know.

Ask each person to find out some interesting or amusing things about their

partner for example, what they like to do, where they live, unusual places that

they have visited, whether they own a pet, etc. The information should not be

too personal or revealing. Each participant has a short time (3-5 minutes) to do

this. Then they must come back to the large group and each person must

introduce their partner to the group based on the information they have gathered.

Debriefing

Without pointing out individuals, it is worth noting that some people seem to have

listened well and remembered the information given them whilst others did not. If

you discuss it in the group, you will probably find that some people took up more

than their share of time talking. This can be pointed out without judgement by

saying that one of the things you hope each person will learn is which skills they

need to work on.

VISTA Unit A1: Understanding the definition and context of school violence

Activity 3 Defining school violence (70 minutes)

Purpose

To be aware of a range of interpretations of school violence

Materials

Resource 1 Individual examples of school violence

Resource 2 The essential characteristics of these examples of school violence

Resource 3 Our definition

Flipchart

Procedure

First, hand out Resource 1 Individual examples of school violence which

participants complete individually. Allow 10 minutes for the individual task. Then

form groups of 4 or 5 and give each group one copy of Resource 2 The essential

characteristics of these examples of school violence. Ask the groups to

complete as a group a summary of the essential characteristics and the

distinctive elements of these individual examples as shown in Resource 2. Allow

30 minutes for this task. Bring all the small groups into the plenary and ask a

representative of each group to present their findings. These are summarised by

the facilitator on a flipchart. Finally, in plenary, the large group tries to formulate

a possible definition of school violence, based on the characteristics and

elements identified by the small groups. The definition is documented by the

facilitator on Resource 3 Our definition. Allow 30 minutes for this part of the

discussion, including the debriefing.

Debriefing

Key discussion points are noted by the facilitator and participants are invited to

comment on the process of arriving at the group definition (or definitions if the

plenary did not reach consensus). Perhaps some people took up more than their

share of time talking. Perhaps some opinions were discounted. The process of

attempting to reach consensus can be discussed without judgement by saying

that the next activity will illustrate the difficulties that experts experience when

trying to arrive at a common definition of school violence.

Activity 4 School violence as defined by international experts (70 minutes)

Purpose

To understand the definition of violence from a range of perspectives

Materials

Resource 4 Definitions by international experts

Procedure

Ask participants to return to their small groups and hand each group a copy of

Resource 4. Ask the groups to compare Our definition with the definitions of the

international experts. Allow 30 minutes for the small group discussion. Ask

participants to return to the plenary where the facilitator notes key points on a

flipchart. Allow 40 minutes for this part of the activity, including the debriefing.

Points for discussion could include the following questions, adapted from Smith

(2003):

1. Is violence necessarily physical?

VISTA Unit A1: Understanding the definition and context of school violence

2. Is violence necessarily against a person?

3. Does violence actually have to be manifested as behaviour that

damages someone or something, or is just the threat of this sufficient?

4. Is violence still violence if it is legal?

5. Does violence have to be done by somebody, or can it be done more

impersonally by a social group or an institution?

6. Has the definition of violence changed over time?

Debriefing

The facilitator ends the activity by pointing out that by thinking, discussing and

working with definitions we are enabled to understand how different opinions and

perspectives arise across cultures and over time. Not only that: the way people

look at school violence determines their attitudes and reactions to it.

Activity 5 The context of school violence (115 minutes)

Purpose

To get participants to identify what they know about the context of school

violence and to listen to the perspectives of others

Materials

Resource 5 Case study of a violent incident

Resource 6 Types of school violence

Resource 7 Summary of case studies

Resource 8 Model of the school system

Procedure

Individual task: The facilitator gives each person a copy of Resource 5 Case

study of a violent incident. Each person is asked to think about and write down a

specific case of school violence that they have experienced or observed. They

are asked to describe the protagonists, events and contexts where this violence

took place and to complete as many of the boxes as they can. Allow 30 minutes

for this part of the activity.

Group task: Participants form small groups of 4-5 people. Each member of the

group shares the example of school violence that they have entered into

Resource 5 Case study of a violent incident. The facilitator then gives each

group a blank copy of Resource 6 Types of school violence and Resource 7

Summary of case studies. Once each example has been shared, the group task

is to reach consensus about how to complete Resources 6 and 7 collectively,

taking into consideration their individual cases. Allow 40 minutes for this part of

the activity.

Plenary: Each small group reports back to the plenary session on their process

of reaching agreement about the content of each of the boxes in Resources 6

and 7. The facilitator summarises the responses from each group on a flipchart

(Resource 7 Summary of case studies). Allow 25 minutes for this part of the

activity.

10

VISTA Unit A1: Understanding the definition and context of school violence

Debriefing (20 minutes)

For this part of the activity the facilitator may find it helpful to use the theoretical

content described in the summary of current thinking (individual, interpersonal,

social, school contexts). It is important to conclude with reference to the links and

influences of different related factors, not only the simple influence of one of them

on school violence. The analysis, using Bronfenbrenners bio-ecological model,

should be continued in the plenary session. Finally, for the analysis of school

context, Resource 8 Model of the school system can be used to synthesise the

findings of the activity with the theoretical points about convivencia as described

in the Summary. The facilitator can indicate how convivencia is facilitated in

schools or how it may be inhibited. This is also an opportunity to share

commonalities and differences in the ways in which the groups have interpreted

the task. Explore what are the most common themes and those that are least

common. Discuss what each person will take away with them to their own school

setting. Compare findings and discuss how they confirm or disconfirm the VISTA

model. Key aspects of the debriefing should include the following:

School violence is a complex phenomenon which requires complex

interventions.

It is important to have a clear definition of violence (Unit A1)

and an analysis of what is happening in our schools (Module D).

We need to select the most relevant and whole interventions for our schools

(see again Modules D and E, for different examples of preventative and

integrative practices).

and share responsibilities inside and outside schools (see Module B).

We need to provide interpersonal and organisational support

and to reflect about the schools we want, and about the education we want

to give our students.

References

Adams, R. E., Bukowski, W. M., & Bagwell, C. (2005). Stability of aggression

during early adolescence as moderated by reciprocated friendship status

and friends aggression. International Journal of Behavioral Development,

29, 139-145.

Baldry, A. C., & Farrington, D. P. (1998). Parents influences on bullying and

victimisation. Legal and Criminological Psychology, 3, 237-254.

Baldry, A. C., & Farrington, D. P. (2000). Bullies and delinquents: Personal

characteristics and parental styles. Journal of Community and Applied

Social Psychology, 10, 17-31.

11

VISTA Unit A1: Understanding the definition and context of school violence

Baldry, A. C., & Farrington, D. P. (2006). Individual risk factors for school

violence. In A. Serrano (Ed.), Acoso y violencia en la escuela (pp. 107133). Ariel: Centro Reino Sofia.

Bennett, S., Farrington, D. P., & Huesmann, L. R. (2004). Explaining gender

differences in crime and violence: The importance of social cognitive skills.

Aggression and Violent Behavior, 10, 263-288.

Bergeron, N., & Schneider, B. H. (2005). Explaining cross-national differences in

peer-directed aggression: A quantitative synthesis. Aggressive Behavior,

31, 116-137.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development. Experiments by

nature and design. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Bronfenbrenner, U., & Morris, P. A. (1998). The ecology of developmental

processes. In W. Damon (Series Ed.) & R. M. Lerner (Vol. Ed.), Handbook

of child psychology: Vol. 1.Theoretical models of human development (5th

ed., pp. 993-1028). New York: John Wiley & Son.

Debarbieux, E. (2003). School violence in Europe Discussion, knowledge and

uncertainty. In Council of Europe Violence in schools A challenge for the

local community. Luxembourg: Council of Europe Publications.

http://www.coe.int/t/e/integrated_projects/violence/06_Our_publications/Viol

ence%20in%20schools%20a%20challenge%20for%20the%20local%20com

munity.pdf

Debarbieux, E., Blaya, C., Vidal, D. (2003). Tackling violence in schools: A

report from France. In P. K. Smith (Ed.), Violence in schools: The response

in Europe (pp. 17-32). London: RoutledgeFalmer.

Depuydt, A., &. Deklerck, J., (1998). An ethical and social interpretation of crime

through the concepts of linkedness and integration-disintegration.

Applications to restorative justice. In L. Walgrave (Ed.), Restorative justice

for juveniles. Potentialities, risks and problems (pp. 137-156). Leuven:

Leuven University Press.

Dodge, K., & Frame, C. (1982). Social cognitive biases and deficits in aggressive

boys. Child Development, 53, 620-635.

Farrington, D. W. (1998). Individual differences and offending. In M. Tonry & M.

H. Moore (Eds.), Youth violence (pp. 421-475). Chicago: University of

Chicago Press.

Finnegan, R. A., Hodges, E. V. E., & Perry, D. G. (1998). Victimization by peers:

Associations with children's reports of mother-child interaction. Journal of

Personality and Social Psychology, 75, 1076-1086.

Hargreaves, A. (2003). Teaching in the knowledge society: Education in the age

of insecurity. New York: Teachers College Press.

Huybregts, I., Vettenburg, N., & DAes, M. (2003). Tackling violence in schools:

A report from Belgium. In P. K. Smith (Ed.), Violence in schools: The

response in Europe (pp. 33-48). London: RoutledgeFalmer.

Menesini, E., Sanchez, V., Fonzi, A., Ortega, R., Costabile, A., & Lo Feudo, G.

(2003). Moral emotions and bullying. A cross-national comparison of

differences between bullies, victims and outsiders. Aggressive Behavior, 29,

515-530.

12

VISTA Unit A1: Understanding the definition and context of school violence

Olweus, D. (1999). Sweden. In P. K. Smith, Y. Morita, J. Junger-Tas, D. Olweus,

R. Catalano, & P. Slee (Eds.), The nature of school bullying: A crossnational perspective (pp. 2-27). London: RoutledgeFalmer.

O'Moore, M. (n.d.). Defining violence: Towards a pupil based definition. NoVAS

RES CONNECT Initiative. Retrieved June 14, 2006, from

http://www.comune.torino.it/novasres/newviolencedefinition.htm

OMoore, M., & Minton, S. (2004). Dealing with bullying in schools: A training

manual for teachers, parents and other professionals. London: Paul

Chapman Publishing.

Ortega, R. (1994). Violencia interpersonal en los centros educativos de

enseanza secundaria. Un estudio sobre maltrato e intimidacin entre

compaeros. Revista de Educacin, 304, 253-280.

Ortega, R. (2003). Enseanza de Prevencin de la Violencia en las Escuelas.

Informe Sobre la Violencia en las Escuelas de Centroamrica. Washington:

BID.

Ortega, R. (2006). Convivencia: A model to prevent violence. In A. Moreno (Ed.),

La convivencia in the classroom: Problems and solutions (pp. 29-44).

Madrid: Ministry of Science and Education.

Ortega, R., del Rey, R., & Mora-Merchn, J. A. (2004). SAVE model: An antibullying intervention in Spain. In P. K. Smith, D. Pepler, & K. Rigby (Eds.),

Bullying in schools: How successful can interventions be? (pp. 167-185).

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ortega, R., del Rey, R., Snchez, V., Ortega-Rivera, J., Mora-Merchn, J., &

Genebat, R. (2003). Violencia escolar en Nicaragua. Ministerio de

Educacin, Cultura y Deportes de Nicaragua.

Ortega, R., & Lera, M. J. (2000). The Seville Anti-bullying in School Project.

Aggressive Behavior, 26, 113-123.

Smith, P. K. (Ed.). (2003). Violence in schools: The response in Europe. London:

RoutledgeFalmer.

Smith, P. K. (1997). Bullying in schools: The UK experience and the Sheffield

Anti-Bullying project. Irish Journal of Psychology, 18, 191-201.

Smith P. K., Bowers, L., Binney, V., & Cowie, H. (1993). Relationships of children

involved in bully/victim problems at school. In S. Duck (Ed.), Understanding

relationships process. Vol. 2: Learning about relationships (pp. 184-212).

Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications.

Smith, P. K., Morita, Y., Junger-Tas, J., Olweus, D., Catalano, R., & Slee, P.

(1999). The nature of bullying. London and New York: Routledge.

Smith, P. K., & Myron-Wilson, R. (1998). Parenting and school bullying. Clinical

Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 3, 405-417.

Smorti, A., Ortega, R., & Ortega, J. (2002). The importance of culture for a theory

of mind: A narrative alternative. Cultura y Educacin, 14(2), 147-159.

Sutton, J., Smith, P. K., & Swettenham, J. (1999). Bullying and theory of mind: A

critique of the 'social skills deficit' view of anti-social behaviour. Social

Development, 8, 117-127.

Vettenburg, N. (1999). Violence in schools. Awareness-raising, prevention,

penalties. General Report. Strasbourg: Council of Europe Publications.

13

VISTA Unit A1: Understanding the definition and context of school violence

Walgrave, L. (1992). Dlinquance systematise des jeunes et vulnrabilitit

socitale. Paris/Gnve: Mridiens/Mdecine et Hygine.

World Health Organization (WHO). (2002). World Report on Violence and Health.

Geneva: Author.

Further reading and additional materials

Books and articles

Gittins, C. (2006) (Ed.). Violence reduction in schools How to make a

difference. Strasbourg: Council of Europe Publications.

Websites

Council of Europe Violence in Schools A Challenge for the Local Community.

Luxembourg: Council of Europe Publications.

http://www.coe.int/t/e/integrated_projects/violence/06_Our_publications/Violence

%20in%20schools%20a%20challenge%20for%20the%20local%20community.pd

f

Council of Europe Responses to violence in everyday life in a democratic society

http://www.coe.int/T/E/Integrated_Projects/violence/

UK Observatory for the Promotion of Non-Violence

http://www.ukobservatory.com

14

VISTA Unit A1: Understanding the definition and context of school violence

Resource 1 Individual examples of school violence

Note down, individually, one or two situations in your school in which violence

occurred.

15

VISTA Unit A1: Understanding the definition and context of school violence

Resource 2 Group discussion of the essential characteristics of

these examples of school violence

Tell one another, in small groups, about your experiences noted in Resource 1

What are the essential characteristics? What are the distinctive elements?

ESSENTIAL CHARACTERISTICS

DISTINCTIVE ELEMENTS

... ...

... ...

... ...

... ...

... ...

... ...

... ...

... ...

... ...

... ...

... ...

... ...

... ...

...

16

VISTA Unit A1: Understanding the definition and context of school violence

Resource 3 Our definition

.

.

.

.

..

.

.

.

.

.

17

VISTA Unit A1: Understanding the definition and context of school violence

Resource 4 Definitions by international experts

DEFINITIONS OF SCHOOL VIOLENCE

GROUP COMMENTS

Violence is defined as behaviour intended to cause injury, but it also includes

threats (Baldry & Farrington, 2006, p. 107).

Violence is not only an exceptional, brutal, unpredictable fact originating

outside school, but also the result of frequent banal irritating, small

aggressions Violence will be viewed through three groups of variables: crime

and offences, micro-violence and the feeling of insecurity (Debarbieux, Blaya,

& Vidal, 2003, p. 18).

De-linquency denotes the absence of an experienced link with the victim(ized

environment), which can be found in the etymological root of the word itself.

Developing, reinforcing or repairing a link of an existential quality with the

environment is therefore a key issue. Persons who are developing a feeling of

linkedness with their environment will deal with it in a different, more

respectful way (Depuydt & Deklerck, 1998, p. 137).

Antisocial behaviour in schools refers to the full spectrum of verbal or non

verbal interactions between persons active in or around the school and involving

malicious or allegedly malicious intentions causing mental, physical or material

damage or injury to persons in or around the school and violating informal rules

of behaviour (Huybregts, Vettenburg, & DAes, 2003, p. 35).

Violence or violent behavior is aggressive behaviour where the actor or

perpetrator uses his or her own body or an object (including a weapon) to inflict

(relatively serious) injury or discomfort upon another individual (Olweus,

1999, p.12).

Violence is aggressive behaviour that may be physically, sexually or

emotionally abusive. The aggressive behaviour is conducted by an individual or

group against another, or others. Physically abusive behaviour, is where a child,

adolescent or group directly or indirectly ill treats, injures, or kills another or

others. The aggressive behaviour can involve pushing, shoving, shaking,

punching, kicking, squeezing, burning or any other form of physical assault on a

person(s) or on property. Emotionally abusive behaviour, is where there is

verbal attacks, threats, taunts, slagging, mocking, yelling, exclusion, and

malicious rumours. Sexually abusive behaviour is where here is sexual assault

or rape (OMoore, n.d.).

http://www.comune.torino.it/novasres/newviolencedefinition.htm

Interpersonal violence and bullying are an illegal way of confronting motives

and needs where one person, group or institution has a dominant role and forces

others to submit to it, being physically, socially and morally harmed (Ortega,

18

VISTA Unit A1: Understanding the definition and context of school violence

2006, p. 31).

The intentional use of physical force or power, threatened or actual, against

oneself, another person, or against a group or a community, that either results in

or has a high likelihood of resulting in injury, death or psychological harm,

maldevelopment or deprivation (WHO, 2002, p. 5).

19

VISTA Unit A1: Understanding the definition and context of school violence

Resource 5 Case study of a violent incident

Participants (Do not use their real names)

What happened among the

participants?

Participants

characteristics

Where did the action take

place?

Related Contextual Factors

You can represent the case with a drawing or diagram if you want:

20

VISTA Unit A1: Understanding the definition and context of school violence

Resource 6 Types of school violence

*

*

*

*

*

*

e.g. social exclusion

21

VISTA Unit A1: Understanding the definition and context of school violence

Resource 7 Summary of case studies

Society

Individual

characteristics

of participants

School context

Dynamics of

interpersonal

relationships

Conclusions

22

VISTA Unit A1: Understanding the definition and context of school violence

Resource 8 Model of the school system

Interpersonal

Relationships

Activity

Discourse

Teachers subsystem

Working

Organization and

cooperation

Teachers/pupils subsystem

TeachingLearning

Culture: scientific and social

knowledge

Pupils/pupils subsystem

Learning

Culture: scientific and social

knowledge

CONVIVENCIA in the school

23

You might also like

- Engl108 Midterm ProjectDocument6 pagesEngl108 Midterm ProjectPearl CollinsNo ratings yet

- School ViolenceDocument37 pagesSchool ViolenceSimona SymonyciNo ratings yet

- Growing Up in Violent Contexts Differential EffectDocument15 pagesGrowing Up in Violent Contexts Differential EffectEuneel EscalaNo ratings yet

- The Effects of Domestic Violence On Academic Performance of Children Upto 16 Years in KenyaDocument19 pagesThe Effects of Domestic Violence On Academic Performance of Children Upto 16 Years in KenyaJablack Angola Mugabe100% (9)

- Bullying in Schools-Psychological Implications and Counselling Interventions PDFDocument9 pagesBullying in Schools-Psychological Implications and Counselling Interventions PDFAlexander DeckerNo ratings yet

- Bullying Among Students and Its Consequences On Health: Barbara Houbre Cyril Tarquinio Isabelle ThuillierDocument26 pagesBullying Among Students and Its Consequences On Health: Barbara Houbre Cyril Tarquinio Isabelle ThuilliershumaiylNo ratings yet

- Bullying Literature Review FinalDocument12 pagesBullying Literature Review FinalRekesha CarterNo ratings yet

- FINAL 3issssd PDFDocument17 pagesFINAL 3issssd PDFKhert BaiganNo ratings yet

- 03 Bullying PaperDocument15 pages03 Bullying PaperNguyễn Minh Đức LêNo ratings yet

- Literature Review On Bullying PDFDocument5 pagesLiterature Review On Bullying PDFc5qxb4be100% (1)

- Children's Bullying Experiences Expressed Through Drawings and Self-ReportsDocument15 pagesChildren's Bullying Experiences Expressed Through Drawings and Self-ReportsyaniNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Bullying On Children and The Interventions Available To Help Those BulliedDocument8 pagesThe Impact of Bullying On Children and The Interventions Available To Help Those BulliedEliza Maria TeşuNo ratings yet

- Understanding Classroom Bullying Climates: The Role of Student Body Composition, Relationships, and Teaching QualityDocument14 pagesUnderstanding Classroom Bullying Climates: The Role of Student Body Composition, Relationships, and Teaching QualityMamaril Ira Mikaella PolicarpioNo ratings yet

- Suggested Citation:"1 Introduction." National AcademiesDocument19 pagesSuggested Citation:"1 Introduction." National AcademiesSameer Voiser AlcalaNo ratings yet

- Bolstering Resilience Melissa InstituteDocument21 pagesBolstering Resilience Melissa InstituteJenniferNo ratings yet

- The Effects of Bullying Experiences On The Academic Performance of The Intermediate Learners in Sambal Elementary School in The District of Lemer1Document41 pagesThe Effects of Bullying Experiences On The Academic Performance of The Intermediate Learners in Sambal Elementary School in The District of Lemer1Jane Atienza100% (1)

- Bullying As A Social ExperienceDocument209 pagesBullying As A Social ExperiencesupergauchoNo ratings yet

- BullyingDocument11 pagesBullyingIrah Olorvida100% (3)

- Módulo 4 - Artigo 2Document14 pagesMódulo 4 - Artigo 2Andreia AfonsoNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Bullying On Social Interactions Among Senior High School Students of Philippine Nikkei Jin Kai International SchoolDocument6 pagesThe Impact of Bullying On Social Interactions Among Senior High School Students of Philippine Nikkei Jin Kai International SchoolLeah Mae PelaezNo ratings yet

- School District Anti Bullying Policies ADocument15 pagesSchool District Anti Bullying Policies Aangeloguilaran123No ratings yet

- BullyingDocument2 pagesBullyingAjeng ClaraNo ratings yet

- Children Who Bully at School - Lodge 2014Document14 pagesChildren Who Bully at School - Lodge 2014xiejie22590No ratings yet

- ch19nikolaouThanosSamsari 4Document11 pagesch19nikolaouThanosSamsari 4ΜπάμπηςΠαπαφλωράτοςNo ratings yet

- Clarene Jane V. Aranas Review of Related LiteratureDocument7 pagesClarene Jane V. Aranas Review of Related Literatureclarene aranasNo ratings yet

- Bullying in SchoolDocument10 pagesBullying in SchoolElfiky90 Elfiky90No ratings yet

- Outline Journal CritiqueDocument7 pagesOutline Journal CritiqueMica MoradaNo ratings yet

- Children and Youth Services Review: Dalhee Yoon, Stacey L. Shipe, Jiho Park, Miyoung YoonDocument9 pagesChildren and Youth Services Review: Dalhee Yoon, Stacey L. Shipe, Jiho Park, Miyoung YoonPriss SaezNo ratings yet

- Bullying EssayDocument3 pagesBullying EssayFatima Fakir100% (1)

- Bullying in SchoolDocument30 pagesBullying in SchoolDimas Aji KuncoroNo ratings yet

- Review of Related Literature About Bullying in SchoolDocument5 pagesReview of Related Literature About Bullying in Schoolfvf2j8q0No ratings yet

- BullyDocument43 pagesBullyAwajiiroijana Uriah OkpojoNo ratings yet

- Influence of BullyingDocument23 pagesInfluence of BullyingDanica FranciscoNo ratings yet

- Bully Prevention in Positive Bahavior SupportDocument59 pagesBully Prevention in Positive Bahavior Supportk.n.e.d.No ratings yet

- Struggles of Bullying Among Junior High School Students: A Case StudyDocument15 pagesStruggles of Bullying Among Junior High School Students: A Case StudyXiannee PisanosNo ratings yet

- Bullying Argumemtative EssayDocument6 pagesBullying Argumemtative Essayapi-302398448No ratings yet

- Child AbuseDocument6 pagesChild AbuseIshanviNo ratings yet

- ProtogerouFlisher 2012 Bullyinginschools Chapter9Document16 pagesProtogerouFlisher 2012 Bullyinginschools Chapter9Rebeka NémethNo ratings yet

- Group 3 Imrad Eapp 1Document8 pagesGroup 3 Imrad Eapp 1Jerwyn Marie CayasNo ratings yet

- Bullying: Age DifferencesDocument8 pagesBullying: Age Differencesgenesis gonzalezNo ratings yet

- Ajol File Journals - 668 - Articles - 249975 - Submission - Proof - 249975 7876 597513 2 10 20230629Document21 pagesAjol File Journals - 668 - Articles - 249975 - Submission - Proof - 249975 7876 597513 2 10 20230629Bashir KanumaNo ratings yet

- Name: Hiba Zahra Class: BS Home Economics Section: B Semester: 2 Subject: Fundamentals of Research Teacher: Miss Faiza ZubairDocument23 pagesName: Hiba Zahra Class: BS Home Economics Section: B Semester: 2 Subject: Fundamentals of Research Teacher: Miss Faiza ZubairHiba ZahraNo ratings yet

- Thesis GuideDocument32 pagesThesis Guidemarianie calibayNo ratings yet

- Fisayomi PROJECT 4Document67 pagesFisayomi PROJECT 4AKPUNNE ELIZABETH NKECHINo ratings yet

- Term Bullying FinalDocument24 pagesTerm Bullying FinalannikaNo ratings yet

- Considering Mindfulness Techniques in School-Based Antibullying ProgrammesDocument7 pagesConsidering Mindfulness Techniques in School-Based Antibullying Programmessantiago maciasNo ratings yet

- Rica Bentoy Research EngDocument21 pagesRica Bentoy Research EngImaginarygirl 903No ratings yet

- Conflict Resolution TacticsDocument16 pagesConflict Resolution TacticsMarlena AndreiNo ratings yet

- Bullying: Ma. Rhea Ann Ano-Os 11-HUMSS CDocument6 pagesBullying: Ma. Rhea Ann Ano-Os 11-HUMSS CRufa Mae BarbaNo ratings yet

- THESISDocument9 pagesTHESISShaynie Tañajura DuhaylungsodNo ratings yet

- Practical ResearchDocument9 pagesPractical ResearchCarmel C. GaboNo ratings yet

- Forensic Aspects of School Bullying-FinalDocument24 pagesForensic Aspects of School Bullying-FinalFathiyah Nurul AzizahNo ratings yet

- 07 - Chapter 2Document48 pages07 - Chapter 2Shaira BailingoNo ratings yet

- Bullying 1Document34 pagesBullying 1Hlatli NiaNo ratings yet

- Bullying and Its Effects On Secondary School Students: BY: A Trishia NavarroDocument14 pagesBullying and Its Effects On Secondary School Students: BY: A Trishia NavarroKanlaon Foto Center & Internet CafeNo ratings yet

- The Association Between Bullying Behaviour, Arousal Levels and Behaviour ProblemsDocument15 pagesThe Association Between Bullying Behaviour, Arousal Levels and Behaviour ProblemsHepicentar NišaNo ratings yet

- JaneRuschel ResearcchPlanDocument6 pagesJaneRuschel ResearcchPlanBRENNDALE SUSASNo ratings yet

- Review of Related LiteratureDocument1 pageReview of Related Literaturekenmark vidalNo ratings yet

- Guidelines For Design and Rating of Gusset-Plate Connections For Steel Truss BridgesDocument12 pagesGuidelines For Design and Rating of Gusset-Plate Connections For Steel Truss BridgesJohn2jNo ratings yet

- British Standard: A Single Copy of This British Standard Is Licensed ToDocument11 pagesBritish Standard: A Single Copy of This British Standard Is Licensed ToJohn2jNo ratings yet

- Development of Rainfall Intensity Duration Frequency Curves For TDocument51 pagesDevelopment of Rainfall Intensity Duration Frequency Curves For TJohn2jNo ratings yet

- Comparative Study of RCC and Prestressed Concrete Flat SlabsDocument4 pagesComparative Study of RCC and Prestressed Concrete Flat SlabsIJMERNo ratings yet

- Light, Life and LoveDocument110 pagesLight, Life and LoveJohn2jNo ratings yet

- 5 Etta Et AlDocument4 pages5 Etta Et AlJohn2jNo ratings yet

- My Is Name Is EkpenyongDocument1 pageMy Is Name Is EkpenyongJohn2jNo ratings yet

- CAD1 AssignmentDocument11 pagesCAD1 AssignmentJohn2jNo ratings yet

- Reflection - Reading and Writing 3Document3 pagesReflection - Reading and Writing 3Quỳnh HồNo ratings yet

- July 2014Document56 pagesJuly 2014Gas, Oil & Mining Contractor MagazineNo ratings yet

- 7540 Physics Question Paper 1 Jan 2011Document20 pages7540 Physics Question Paper 1 Jan 2011abdulhadii0% (1)

- Top Survival Tips - Kevin Reeve - OnPoint Tactical PDFDocument8 pagesTop Survival Tips - Kevin Reeve - OnPoint Tactical PDFBillLudley5100% (1)

- A Mini-Review On New Developments in Nanocarriers and Polymers For Ophthalmic Drug Delivery StrategiesDocument21 pagesA Mini-Review On New Developments in Nanocarriers and Polymers For Ophthalmic Drug Delivery StrategiestrongndNo ratings yet

- La La Mei Seaside Resto BAR: Final PlateDocument4 pagesLa La Mei Seaside Resto BAR: Final PlateMichael Ken FurioNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0378432004002465 MainDocument20 pages1 s2.0 S0378432004002465 MainMuhammad JameelNo ratings yet

- Mastering American EnglishDocument120 pagesMastering American Englishmarharnwe80% (10)

- Chapter 3.seed CertificationDocument9 pagesChapter 3.seed Certificationalemneh bayehNo ratings yet

- Advantages of The CapmDocument3 pagesAdvantages of The Capmdeeparaghu6No ratings yet

- Enzymes WorksheetDocument5 pagesEnzymes WorksheetgyunimNo ratings yet

- How Do I Predict Event Timing Saturn Nakshatra PDFDocument5 pagesHow Do I Predict Event Timing Saturn Nakshatra PDFpiyushNo ratings yet

- Venere Jeanne Kaufman: July 6 1947 November 5 2011Document7 pagesVenere Jeanne Kaufman: July 6 1947 November 5 2011eastendedgeNo ratings yet

- HSG 2023 KeyDocument36 pagesHSG 2023 Keyle827010No ratings yet

- Machine Tools PDFDocument57 pagesMachine Tools PDFnikhil tiwariNo ratings yet

- Study of Subsonic Wind Tunnel and Its Calibration: Pratik V. DedhiaDocument8 pagesStudy of Subsonic Wind Tunnel and Its Calibration: Pratik V. DedhiaPratikDedhia99No ratings yet

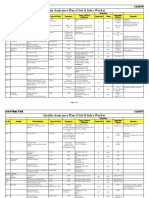

- Quality Assurance Plan - CivilDocument11 pagesQuality Assurance Plan - CivilDeviPrasadNathNo ratings yet

- Madam Shazia PaperDocument14 pagesMadam Shazia PaperpervaizhejNo ratings yet

- English 6, Quarter 1, Week 7, Day 1Document32 pagesEnglish 6, Quarter 1, Week 7, Day 1Rodel AgcaoiliNo ratings yet

- ICON Finals Casebook 2021-22Document149 pagesICON Finals Casebook 2021-22Ishan ShuklaNo ratings yet

- Case Studies InterviewDocument7 pagesCase Studies Interviewxuyq_richard8867100% (2)

- 4.9 Design of Compression Members: L 4.7 UsingDocument22 pages4.9 Design of Compression Members: L 4.7 Usingctc1212100% (1)

- IRJ November 2021Document44 pagesIRJ November 2021sigma gaya100% (1)

- Lesson 3 - Adaptation AssignmentDocument3 pagesLesson 3 - Adaptation AssignmentEmmy RoseNo ratings yet

- Old Man and The SeaDocument10 pagesOld Man and The SeaXain RanaNo ratings yet

- A Wicked Game by Kate BatemanDocument239 pagesA Wicked Game by Kate BatemanNevena Nikolic100% (1)

- Flange CheckDocument6 pagesFlange CheckMohd. Fadhil JamirinNo ratings yet

- English 8 q3 w1 6 FinalDocument48 pagesEnglish 8 q3 w1 6 FinalJedidiah NavarreteNo ratings yet

- B1 Editable End-of-Year TestDocument6 pagesB1 Editable End-of-Year TestSyahira Mayadi50% (2)