Professional Documents

Culture Documents

J Linged 2004 02 004

Uploaded by

Lata DeshmukhOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

J Linged 2004 02 004

Uploaded by

Lata DeshmukhCopyright:

Available Formats

EDITORIAL

Introduction to Proposed

Special Issue: Popular Culture

and Classroom Language

Learning

Attention to the role of popular culture in language classrooms is by no means

new. In the 1970s scholars proposed the use of popular culture as an alternative to the traditional literary canon then predominant in the English language

arts curriculum (see, e.g., Kirby, 1976). Early scholarship argued that integrating popular culture into language classrooms could render the curriculum more

relevant to students lives and hence lead to greater interest and motivation to

learn.

Since then, interest in media and popular culture has intensified as electronic

media have proliferated (Arnett, 1995). Influenced by the emerging fields of critical media studies (see Hall, 1997) and critical media literacy (see Alvermann,

Moon, & Hagood, 1999), we increasingly view communication as an interchange

of multilayered and multimodal semiotic signs. Electronic media, often infused

with popular culture, embed spoken and written language in other forms of symbolic communication including graphics, photography, video, and music (see, e.g.,

Moje, 2000). Some claim that this proliferation of media and popular culture has effected changes in the very cultural environment of industrialized societies (Arnett,

1995). In particular, while popular culture was once considered exclusive to private

spheres or lifeworlds (Gee, 2000), it is now making incursions into public institutions such as schools. As a result, popular culture has become an increasingly

significant issue in both first and second language and literacy research. Scholars (e.g., Alvermann et al., 1999; Cope & Kalantzis, 2000; Dyson, 1997; Gee,

2000; Knobel, 1999) contend that the infusion of multimedia and pop culture referents across social domains is changing the very meaning of what it means to be

proficient and literate in a language.

Direct all correspondence to: Linda Harklau, Departnemt of Language Education, 125 Aderhold Hall,

University of Georgia, Athens, GA 30602, USA. E-mails: lharklau@coe.uga.edu, zuengler@wisc.edu

Linguistics and Education 14: 227230.

Copyright 2004 Elsevier Inc.

All rights of reproduction in any form reserved.

ISSN: 0898-5898

228

EDITORIAL

Yet the role of popular culture in schooling is by no means uncomplicated and

is often marked by ambivalence. One of the original reasons that advocates in

the 1970s argued for the incorporation of popular culture in classrooms was its

entertaining and engaging nature (Alvermann & Heron, 2001, Lotherington, this

issue; Rymes, this issue). It can evoke a sense of irreverence and transgression that

is pleasurable. At the same time, however, popular culture can be violent, profane,

sexist, and racist and thus not represent values that educators want to endorse or

perpetuate. It is often tied to youth cultures (James, 1995) and thus engages children

and adolescents in ways that implicitly or explicitly exclude adult educators (see

Rymes, this issue). Popular culture also poses major challenges in a pluralistic

society since it is often more culturally specific than transcendent. As such, it can

be deployed as a boundary marker for social groups. It can be used to exclude

not only adult educators but also peers within the same classroom who do not

share the same cultural identities and understandings (see Duff, this issue). Also,

as Zuengler (this issue) notes, popular culture is frequently produced or coopted

by major international corporate interests and attempts to manipulate youth as

consumers. As a result, there can be disconnects and even competition between

media-based popular culture and family or school-based language and literacy

practices (Alvermann & Heron, 2001; Arnett, 1995).

Nevertheless, in spite of our ambivalence, as Lotherington (this issue) points

out, we as language educators ignore popular culture at our peril. It is crucial

to understand the role of popular culture in language and literacy development

given that children and youth are the greatest consumers of media (Arnett, 1995).

Overlooking it may result in a curriculum that is out of step with students and

societys lived experience outside of school.

In spite of accelerating interest in the semiotics of popular culture, to date there

has been very little linguistic work documenting how, when, and why popular

culture referents are taken up in educational settings. This special issue provides

four diverse and complementary perspectives on how popular culture is (or is not)

discursively manifested in classroom language and literacy practices.

Drawing upon notions of intertextuality (Bloome & Egan-Robertson, 1993)

and discursive hybridity (Gutirrez, Larson, & Rymes, 1995), Patricia Duff analyzes the linguistic, social, cognitive and affective features of pop-culture-infused

talk in Canadian high school classrooms. Specifically, Duff shows how popular

culture functions as a resource for the display and contestation of teachers and

students various social and cultural identities in classrooms. Duff also suggests

that knowledge of pop culture is unevenly distributed in multilingual and multicultural classrooms and explores consequences for classroom communication.

Jane Zuengler draws on Gees (1999) conception of cultural model to understand the functions of popular culture in one U.S. high school sheltered civics class.

Zuengler closely examines classroom interactions among language minority students, their teacher, and translator aide regarding popular culture and consumerism

EDITORIAL

229

on issues such as propaganda, endorsements, and impulse buying. She asks

how language is used to selectively validate cultural models and looks at beliefs

and value judgments inherent in these models. Zuengler also illustrates how popular culture functions in classroom discourse to construct, reflect, and resist cultural

models (Gee, 1999; Giroux, 1994).

Heather Lotherington documents a disconnect between standardized language

and literacy tests and childrens literacy practices. Drawing on case studies of youth

in the Toronto area, Lotherington documents how children acquire digital literacies

through screen-based play mechanisms (e.g., video games and interactive internet usage), pop culture socialization, and postmodern metaliteracies. Lotherington

suggests that childrens language and literacy practices in peer-mediated, pop culture saturated interactive media extend beyond the boundaries of many classroom

teachers proficiencies. She further finds that these practices may be polarized from

the literacy practices evaluated in mandated province-wide, standardized literacy

testing.

Finally, Betsy Rymes illustrates how words layered with pop cultural meanings infiltrate one elementary classroom phonics lesson. Rymes shows how these

words provide a means for English language learners to display communicative

competence as well as to index their membership in a group of competent English speakers. However, at the same time, she also finds that the very fact that

these words are associated with childrens popular culture threatens the teachers

identity as competent language instructor. Rymes argues that the contrast between

students and the teachers zones of comfortable competence reveals the necessarily community-based, context-dependent nature of communicative competence.

REFERENCES

Alvermann, D. E., & Heron, A. H. (2001). Literacy identity work: Playing to learn with popular media.

Journal of Adolescent and Adult Literacy, 45, 118.

Alvermann, D. E., Moon, J. S., & Hagood, M. C. (Eds.). (1999). Popular culture in the classroom:

Teaching and researching critical media literacy. Newark, DE and Chicago, IL: International

Reading Association and National Reading Conference.

Arnett, J. J. (1995). Adolescents use of media for self-socialization. Journal of Youth and Adolescence,

24, 519533.

Bloome, D., & Egan-Robertson, A. (1993). The social construction of intertextuality in classroom

reading and writing lessons. Reading Research Quarterly, 28, 304333.

Cope, B., & Kalantzis, M. (Eds.). (2000). Multiliteracies: Literacy learning and the design of social

futures. New York: Routledge.

Dyson, A. (1997). Writing superheroes: Contemporary childhood, popular culture, and classroom

literacy. New York: Teachers College Press.

Gee, J. P. (1999). An introduction to discourse analysis: Theory and method. New York: Routledge.

Gee, J. P. (2000). Teenagers in new times: A new literacy studies perspective. Journal of Adolescent

and Adult Literacy, 43, 412420.

230

EDITORIAL

Giroux, H. A. (1994). Disturbing pleasures: Learning popular culture. New York: Routledge.

Gutirrez, K., Larson, J., & Rymes, B. (1995). Script, counterscript, and underlife in the classroom:

James Brown versus Brown v. Board of Education. Harvard Educational Review, 65, 445471.

Hall, S. (1997). The work of representation. In S. Hall (Ed.), Representation: Cultural representation

and signifying practices (pp. 1364). London, Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

James, A. (1995). Talking of children and youth: Language, socialization and culture. In V. Amit-Talai &

H. Wulff (Eds.), Youth cultures: A cross-cultural perspective (pp. 4362). New York: Routledge.

Kirby, D. (1976). Popular culture in the English classroom. English Journal, 65(3), 3234.

Knobel, M. (1999). Everyday literacies: Students, discourse, and social practice. New York: Peter

Lang.

Moje, E. B. (2000). To be part of the story: The literacy practices of gansta adolescents. Teachers

College Record, 102, 651690.

Linda Harklau

Departnemt of Language Education

University of Georgia, 125 Aderhold Hall

Athens, GA 30602, USA

Jane Zuengler

Departnemt of English

University of Wisconsin-Madison

600 N. Park St., Madison, WI 53706, USA

You might also like

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Natural ApproachDocument204 pagesThe Natural ApproachVal RibeiroNo ratings yet

- EngDocument19 pagesEngshrikanhaiyyaNo ratings yet

- WECAN LifetimeOfJoyDocument128 pagesWECAN LifetimeOfJoyTourya Morchid100% (1)

- Problems of Pakistan Education and SolutionDocument11 pagesProblems of Pakistan Education and Solutionmudassar bajwa50% (2)

- Unit 3: Senior High SchoolDocument6 pagesUnit 3: Senior High SchoolThelmzNo ratings yet

- Gepi 1370100621Document5 pagesGepi 1370100621Lata DeshmukhNo ratings yet

- (Micro) Fads Asset Evidence: FuturesDocument23 pages(Micro) Fads Asset Evidence: FuturesLata DeshmukhNo ratings yet

- Covalent Immobilization of and Glucose Oxidase On Carbon ElectrodesDocument5 pagesCovalent Immobilization of and Glucose Oxidase On Carbon ElectrodesLata DeshmukhNo ratings yet

- BF 01045789Document6 pagesBF 01045789Lata DeshmukhNo ratings yet

- Electrochemical and Catalytic Properties of The Adenine Coenzymes FAD and Coenzyme A On Pyrolytic Graphite ElectrodesDocument7 pagesElectrochemical and Catalytic Properties of The Adenine Coenzymes FAD and Coenzyme A On Pyrolytic Graphite ElectrodesLata DeshmukhNo ratings yet

- BF 00551954Document4 pagesBF 00551954Lata DeshmukhNo ratings yet

- Factor Analysis of Spectroelectrochemical Reduction of FAD Reveals The P K of The Reduced State and The Reduction PathwayDocument9 pagesFactor Analysis of Spectroelectrochemical Reduction of FAD Reveals The P K of The Reduced State and The Reduction PathwayLata DeshmukhNo ratings yet

- Elan 200904691Document8 pagesElan 200904691Lata DeshmukhNo ratings yet

- Homogenous Assay of FADDocument6 pagesHomogenous Assay of FADLata DeshmukhNo ratings yet

- Fid, Fads: If Cordorate Governance Is A We Need MoreDocument1 pageFid, Fads: If Cordorate Governance Is A We Need MoreLata DeshmukhNo ratings yet

- BF 01456737Document8 pagesBF 01456737Lata DeshmukhNo ratings yet

- Bin 305Document18 pagesBin 305Lata DeshmukhNo ratings yet

- BF 00314252Document2 pagesBF 00314252Lata DeshmukhNo ratings yet

- Infrared Spectroscopic Study of Thermally Treated LigninDocument4 pagesInfrared Spectroscopic Study of Thermally Treated LigninLata DeshmukhNo ratings yet

- 28sici 291097 4547 2819990301 2955 3A5 3C629 3A 3aaid jnr10 3e3.0.co 3B2 yDocument14 pages28sici 291097 4547 2819990301 2955 3A5 3C629 3A 3aaid jnr10 3e3.0.co 3B2 yLata DeshmukhNo ratings yet

- 28sici 291099 1255 28199601 2911 3A1 3C41 3A 3aaid Jae364 3e3.0.co 3B2 RDocument18 pages28sici 291099 1255 28199601 2911 3A1 3C41 3A 3aaid Jae364 3e3.0.co 3B2 RLata DeshmukhNo ratings yet

- Task Group Osition Paper On Unbiased Assessment of CulturallyDocument5 pagesTask Group Osition Paper On Unbiased Assessment of CulturallyLata DeshmukhNo ratings yet

- Apj 526Document7 pagesApj 526Lata DeshmukhNo ratings yet

- Production of Recombinant Cholesterol Oxidase Containing Covalently Bound FAD in Escherichia ColiDocument10 pagesProduction of Recombinant Cholesterol Oxidase Containing Covalently Bound FAD in Escherichia ColiLata DeshmukhNo ratings yet

- Editorial: Etiology Nutritional Fads: WilliamDocument4 pagesEditorial: Etiology Nutritional Fads: WilliamLata DeshmukhNo ratings yet

- Amperometric Assay Based On An Apoenzyme Signal Amplified Using NADH For The Detection of FADDocument4 pagesAmperometric Assay Based On An Apoenzyme Signal Amplified Using NADH For The Detection of FADLata DeshmukhNo ratings yet

- Ortho-Para-H2: Fads in Research - Fullerite Versus ConversionDocument3 pagesOrtho-Para-H2: Fads in Research - Fullerite Versus ConversionLata DeshmukhNo ratings yet

- FILM Cu S/CD 1Document9 pagesFILM Cu S/CD 1Lata DeshmukhNo ratings yet

- Spectroscopic Study of Molecular Associations Between Flavins FAD and RFN and Some Indole DerivativesDocument6 pagesSpectroscopic Study of Molecular Associations Between Flavins FAD and RFN and Some Indole DerivativesLata DeshmukhNo ratings yet

- FAD Mediates Electron Transfer Between Platinum and BiomoleculesDocument11 pagesFAD Mediates Electron Transfer Between Platinum and BiomoleculesLata DeshmukhNo ratings yet

- Spectroscopic Study of The Molecular Structure of A Lignin-Polymer SystemDocument5 pagesSpectroscopic Study of The Molecular Structure of A Lignin-Polymer SystemLata DeshmukhNo ratings yet

- Spectroscopic Study of Intermolecular Complexes Between FAD and Some Fl-Carboline DerivativesDocument5 pagesSpectroscopic Study of Intermolecular Complexes Between FAD and Some Fl-Carboline DerivativesLata DeshmukhNo ratings yet

- Integrated Project Development Teams: Another F A D - ., or A Permanent ChangeDocument6 pagesIntegrated Project Development Teams: Another F A D - ., or A Permanent ChangeLata DeshmukhNo ratings yet

- 0162 0134 2895 2997735 9Document1 page0162 0134 2895 2997735 9Lata DeshmukhNo ratings yet

- 0142 1123 2896 2981249 7Document1 page0142 1123 2896 2981249 7Lata DeshmukhNo ratings yet

- Catholic High School Sec 3 Subject Combination OptionsDocument3 pagesCatholic High School Sec 3 Subject Combination OptionsHans Chen0% (2)

- Mabini AcademyDocument56 pagesMabini AcademyMaricris TumpangNo ratings yet

- Daily English lesson log for 11th gradeDocument4 pagesDaily English lesson log for 11th gradeKristal Macasaet MauhayNo ratings yet

- Private school fees determined for Trichy district 2013-2016Document75 pagesPrivate school fees determined for Trichy district 2013-2016Ashok KumarNo ratings yet

- KV Kankinara Interview 2021Document5 pagesKV Kankinara Interview 2021AlokNo ratings yet

- Pamela L. Ollinger Chapter AE P.E.O. SisterhoodDocument2 pagesPamela L. Ollinger Chapter AE P.E.O. Sisterhoodgregory_glass4280No ratings yet

- Cabuluan Es Quarterly Accomplishment Report 2019-2020Document18 pagesCabuluan Es Quarterly Accomplishment Report 2019-2020Ruel Gapuz ManzanoNo ratings yet

- AP Dept Tests-Eo Test Held On 18-07-2011 - Results With Names-KarimnagarDocument19 pagesAP Dept Tests-Eo Test Held On 18-07-2011 - Results With Names-KarimnagarNarasimha SastryNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2Document8 pagesChapter 2Abby CardeñoNo ratings yet

- How School Lessons Reflect Social ClassDocument27 pagesHow School Lessons Reflect Social ClassDanielle PiferNo ratings yet

- Log Book - Ansal School of Architecture - Docx 4t Year PDFDocument7 pagesLog Book - Ansal School of Architecture - Docx 4t Year PDFsameen rizviNo ratings yet

- Third Q Module 2Document15 pagesThird Q Module 2Tyrone Dave BalitaNo ratings yet

- Collection PolicyDocument3 pagesCollection Policyapi-283167925No ratings yet

- Form 137 Request FormDocument2 pagesForm 137 Request FormApple Pearl PasayloNo ratings yet

- 2018 Provincial Academic OlympicsDocument2 pages2018 Provincial Academic OlympicsDJ GonzalesNo ratings yet

- Reading Comprehension TEXT 2Document3 pagesReading Comprehension TEXT 2Michele LangNo ratings yet

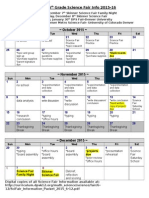

- Skinner 6 Grade Science Fair Info 2015-16: Projects DueDocument7 pagesSkinner 6 Grade Science Fair Info 2015-16: Projects Dueapi-298890663No ratings yet

- Singapore Malays' Attitudes Towards Education: Overcoming ImpedimentsDocument147 pagesSingapore Malays' Attitudes Towards Education: Overcoming ImpedimentsNor Fadhilah Bt AbdullahNo ratings yet

- Teacher Perceptions of the New Normal EducationDocument22 pagesTeacher Perceptions of the New Normal Educationjasmin grace tanNo ratings yet

- ToT On Test ConstructionDocument33 pagesToT On Test ConstructionglaidzNo ratings yet

- NTSE 2015 Stage I Official Result Karnataka PDFDocument10 pagesNTSE 2015 Stage I Official Result Karnataka PDFAnnu NaikNo ratings yet

- DDL - Icarus and DaedalusDocument3 pagesDDL - Icarus and DaedalusKezruz MolanoNo ratings yet

- Trip Ura PSCDocument3 pagesTrip Ura PSCJeshiNo ratings yet

- Admit12sourav PDFDocument1 pageAdmit12sourav PDFNeelava BiswasNo ratings yet

- GEMARIEDocument2 pagesGEMARIERyuzaki RenjiNo ratings yet