Professional Documents

Culture Documents

NewbornSurvival Prasantha

Uploaded by

Prabir Kumar ChatterjeeOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

NewbornSurvival Prasantha

Uploaded by

Prabir Kumar ChatterjeeCopyright:

Available Formats

Policy Forum

Improving Newborn Survival in Low-Income Countries:

Community-Based Approaches and Lessons from South

Asia

Nirmala Nair1, Prasanta Tripathy1, Audrey Prost2, Anthony Costello2, David Osrin2*

1 Ekjut, Chakradharpur, West Singhbhum, Jharkhand, India, 2 UCL Centre for International Health and Development, Institute of Child Health, University College London,

United Kingdom

The Scale of the Problem Home Births and Limited Access to Content of Health Care

Until about twenty years ago, child

Care The three commonest causes of neona-

In low-income settings, most babies are tal deaths are infections (28%), complica-

survival meant the survival of children tions of prematurity (30%), and intrapar-

born at home and more than half of those

rather than newborn infants. With a steady tum-related (‘‘birth asphyxia’’) (24%) [2].

who die do so at home. Three-quarters of

worldwide decline in under-5 deaths— Unfortunately, health workers may lack

neonatal deaths occur in the first week,

most of the lives saved being those of the skills and experience necessary to act

and just under half in the first 24 h [3]. In

infants and children over the age of a appropriately. Basic resuscitation skills and

South Asia and East and Southern Africa,

month—the newborn period has come into knowledge may be limited, and there is a

only about 35% of births take place in

focus as a relatively intransigent source of pervasive idea that intervention needs to

institutions [8]. The newborn infant has

mortality. The ‘‘child survival revolution’’ be highly technical. This is not generally

traditionally occupied a transitional space

increased child survival [1], but newborn true. As early as 1905, Budin recommend-

between potential and actual personhood,

infants went largely unnoticed. Neonatal ed resuscitation, warmth, early and fre-

and seclusion practices add to the likeli-

mortality (0–28 d) now accounts for about quent breastfeeding, keeping the baby

hood that he or she will be invisible to

two-thirds of global infant (0–1 y) mortality with his or her mother, hygiene, and

health professionals. If care is sought, it is

and about 3.8 million of the 8.8 million prompt recognition and treatment of

often in the traditional sector and beset by

annual deaths of children under 5 [2]. Most illness [10]. Contemporary recommenda-

obstacles such as the notion that mother

of these deaths (98%) occur in low- and tions for ‘‘essential newborn care’’ follow

and baby are polluted, which may entail

middle-income countries [3]. this blueprint [11,12]. The Lancet’s series on

seclusion and cause delay in care-seeking.

The last two decades have seen a rise in neonatal survival suggested that between

Access to allopathic (‘‘Western’’ or bio-

advocacy—a call for attention to the 41% and 72% of neonatal deaths could be

medical) health services is limited by lack

newborn infant along with her mother averted if 16 simple, cost-effective inter-

of facilities, human resources, equipment,

and siblings—and an incremental growth ventions were delivered with universal

and consumables.

in the evidence for potential interventions coverage. Among these are adequate

There are four general ways of address-

[4–6]. Reducing neonatal mortality is both nutrition, improved hygiene, antenatal

ing this: improving the provision and

an ethical obligation and a prerequisite to care, skilled birth attendance, emergency

quality of institutional health care, extend-

achieving Millennium Development Goal obstetric and newborn care, and postnatal

ing institutional care through community

4, the target of which is a reduction in visits for mothers and infants [13].

outreach, stimulating demand for appro-

child mortality by two-thirds between

priate health care and institutional deliv-

1990 and 2015. A 2008 report found only Inequity

ery through community engagement and

a quarter of relevant countries on track to

perhaps financial incentives, and changing Newborn survival increases with wealth.

reach this target [7].

ideas and behaviour by working with In India, for example, neonatal mortality

communities. These approaches are far is 56 per 1,000 in the poorest quintile, but

Immediate Challenges from mutually exclusive and should be 25 in the richest [14]. Such inequality is

The main obstacles to improving new- joined up [9]. evident no matter how the population is

born survival are that many babies are

born at home without skilled attendance, Citation: Nair N, Tripathy P, Prost A, Costello A, Osrin D (2010) Improving Newborn Survival in Low-Income

care-seeking for maternal and newborn Countries: Community-Based Approaches and Lessons from South Asia. PLoS Med 7(4): e1000246. doi:10.1371/

journal.pmed.1000246

ailments is limited, health workers are

often not skilled and confident in caring Published April 6, 2010

for newborn infants, and inequalities in all Copyright: ß 2010 Nair et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative

Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

these factors are felt by those most in need. provided the original author and source are credited.

Funding: DO is supported by The Wellcome Trust (081052/Z/06/Z). The funder played no role in the decision

The Policy Forum allows health policy makers to submit the article or in its preparation.

around the world to discuss challenges and Competing Interests: David Osrin is on the Editorial Board of PLoS Medicine.

opportunities for improving health care in their

societies. * E-mail: d.osrin@ich.ucl.ac.uk

Provenance: Commissioned; externally peer-reviewed.

PLoS Medicine | www.plosmedicine.org 1 April 2010 | Volume 7 | Issue 4 | e1000246

Summary Points them successful and all of them originating

in low-income countries—and the incor-

poration of their findings into national and

N Reducing global neonatal mortality is crucial. In low-income countries, most

births and deaths occur at home. international guidelines. It is true that

community-driven approaches fall some-

N Obstacles to improving survival include: many newborn infants are invisible to what outside the prevailing health sector

health services; care-seeking for maternal and newborn ailments is limited;

paradigm (in reality if not in principle), but

health workers are often not skilled and confident in caring for newborn infants;

they raise important questions about

and there are inequalities across all these factors.

integration, which we will discuss later.

N The best community-based approach is a combination of community Table 1 summarises published controlled

mobilization and home visits by community-based workers. Both timing of

trials in which the interventions under test

visits and treatment interventions are critical.

included one or more of three broad

N It is not clear how community-based approaches should be balanced, and strategies: community mobilization initia-

whether they are effective outside South Asia and when introduced into public tives, programmes that involved home

sector systems. Operational challenges include integrating community-based visits by community-based workers, and

activities into public health systems, and questions of how to achieve coverage

partnerships with traditional birth atten-

at scale.

dants (TBAs).

N The possibility of partnership between the public and nongovernment sectors

should be explored, particularly in terms of novel large-scale collaborations.

Community Mobilization

All the suggested approaches to improv-

ing newborn survival involve a degree of

segmented: by education, ethnicity, mi- general risk reduction is debated [21,22], it

community mobilization. While general

grant status, or occupation [15]. In many can be delivered in the home. The same is community development programmes

countries, the responsibility to provide true of postnatal care, and both phases of may improve newborn survival, our expe-

health care for poorer people falls on the ambulatory care are included in commu- rience in India and Nepal suggests that

public sector. As wealthier members of nity-based interventions. Training skilled survival-focused interventions may reduce

society move steadily towards private birth attendants is central to current efforts neonatal mortality rates even more effi-

sector care, the burden of care for to improve maternal outcomes and is ciently. Here we emphasise programs in

increasing numbers of poor people falls included in health plans in many low- which work with communities to identify

on already overstretched national public income countries. However, the rate of problems and solutions is a specific

health systems. output is limited and unlikely to answer strategy to increase newborn survival.

demand in the next 10 y [23]. Linked with The idea that communities can develop

What Is Meant by Community this is the provision of skilled intrapartum insight into and solutions for their own

Intervention? care at primary health care centres, which problems has a long history and social and

is the focus of recommendations for political implications [29,30]. A stimulus

Figure 1 summarises both the compo- maternal survival [24]. Both transport for newborn survival initiatives came from

nents of health care that have been and referral remain problematic in many Bolivia’s Warmi program, which worked

recommended to improve newborn sur- countries. with rural Aymara women’s groups to

vival and the range of delivery strategies The issue is not only geographical identify local opportunities and develop

that have been proposed, tested, or movement between health care institutions strategies to improve maternal and new-

introduced. More detail can be found in but also realisation that a problem exists born health [31]. Groups moved through

a recent set of systematic reviews on and communication and decision-making a cycle of discussions that encompassed

intrapartum-related deaths [16–20]. Preg- for referral. A maternity waiting home is a sharing of experiences, internalising new

nancy is just one stage of a woman’s life, residence near a hospital to which women information, prioritising, strategising, ac-

and the figure reminds us that it may at risk move shortly before delivery or if tion, and evaluation. In a modified version

occur on a background of gender inequal- complications arise [25]. The benefits of this process, in rural Nepal, a cluster

ity. Inadequate education, nutrition, and have not been demonstrated conclusively, randomised trial suggested that women’s

care for childhood illness have short- and risk screening may be of limited use, and groups facilitated by a local female com-

long-term effects that are not limited to community acceptance varies, but waiting munity worker—trained in facilitation

women (although the burdens often fall on homes are an option in some settings and techniques but without a health care

them, as do young age at marriage and a strategy adopted in Cuba, for example. background—could reduce neonatal mor-

conception, short birth intervals, and Cost reduction is an overarching means of tality rates by about 30% [32]. There were

undesirably large families). stimulating demand for health services behaviour changes in, for example, hy-

The figure locates intervention strate- [26]. Strategies include the removal of gienic practices and care-seeking for

gies in terms of their proximity to a user fees [27], conditional cash transfers problems, and also strategic initiatives

woman’s home. Some approaches deserve for use of services [28], and insurance such as maternal and child health funds

fuller comment than we can give here. schemes. and transport schemes. Seventy-five per-

Antenatal care is, and should remain, a All the potential approaches serve cent of groups remained active 18 mo

feature of health care systems. It allows communities, but we will focus on the after withdrawal of program support. The

contact between women and health work- beginning of the sequence close to home model is being tested with rural groups in

ers and strengthens the likelihood of birth (highlighted in Figure 1), in which the Bangladesh [33], India [34], and Malawi

preparedness and institutional delivery. It essential feature is not primarily institu- [35] and in urban slums in India [36].

may identify certain remediable issues, tional. We do so in response to a number Group work, not necessarily confined to

and although its effectiveness in terms of of recent research programs—most of women, and with varying degrees of

PLoS Medicine | www.plosmedicine.org 2 April 2010 | Volume 7 | Issue 4 | e1000246

Figure 1. Maternity as a life event, components of care with potential effects on newborn survival, and 11 possible delivery

strategies.

doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000246.g001

intensity, was also a feature of other women and make antenatal care visits to based women trained and remunerated by

successful programs [37,38,39]. their homes, attend delivery, give vitamin SEARCH. These local nongovernment

K injections, make several further postna- workers were able to give advice and

Home Visits by Community Workers tal home visits, identify and manage identify and treat neonatal problems, their

Aside from the benefits of group-based infants at risk from birth asphyxia, low skills extending to resuscitation and ad-

discursive approaches, a growing number birth weight and sepsis, and encourage ministration of intramuscular antibiotics.

of programs have shown that targeted appropriate referral. This seminal model Since then, trials of home-based care have

home visits by community-based workers gradually reduced neonatal mortality by been conducted in North India [37],

can help reduce newborn mortality. The 70% [40,41]. Bangladesh [38], and Pakistan [39] (sum-

idea developed over some years in rural Like most successful local initiatives, the marised along with other key work in

Maharashtra, India, where the nongov- SEARCH approach developed incremen- Table 1). Strategies differed in personnel

ernment organisation (NGO), the Society tally in the context of a commitment to and content. All the programs included

for Education, Action and Research in community development and included a community meetings, antenatal and post-

Community Health (SEARCH) trained range of activities. The most prominent natal home visits, and preventive advice.

community health workers to conduct were regular visits to women and their The Hala program included referral [39],

group health education, identify pregnant newborn infants by a cadre of community- as did the Projahnmo program, which also

PLoS Medicine | www.plosmedicine.org 3 April 2010 | Volume 7 | Issue 4 | e1000246

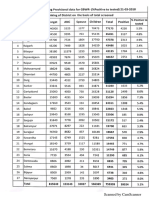

Table 1. Components of interventions and key features of controlled trials of community-based approaches to improve newborn

survival.

Population Evaluation Neonatal Mortality Rate

Who Did the Intervention? What Did They Do? Involved Design Effect: Odds Ratio (95% CI)

Bangladesh: Beanibazar, 480,000 Cluster RCT

Zakiganj and Kaighat

subdistricts, Sylhet [38]

‘‘Home care’’ 0.7 (0.5–0.9)

Community health worker Identified pregnancies through surveillance

every 2 wk.

Made 2 antenatal home visits.

Provided iron and folic acid supplements.

Made 3 postnatal home visits.

Identified illness in infants.

Managed sepsis with injectable antimicrobials and

referred.

Completed management if referral was unsuccessful.

Female community mobiliser Facilitated community group meetings every 4 mo.

Male community mobiliser Facilitated community group meetings.

‘‘Community care’’ No effect seen

Female community mobiliser Facilitated community group meetings every 8 mo.

Male community mobiliser Facilitated community group meetings every 10 mo.

Community resource person Identified pregnant women.

Encouraged meeting attendance.

India: Gadchiroli, 80,000 Single control 0.3 (0.2–0.4)

Maharashtra [40,41]

Community health worker Identified pregnant women.

Conducted group health education.

Made 2 antenatal home visits.

Attended delivery, gave vitamin K injection.

Made 8–12 postnatal home visits.

Weighed infants and identified and managed high-risk

infants (birth asphyxia, sepsis, low birth weight).

Encouraged appropriate referral.

Recorded monitoring information.

Supervisor Supervised community health workers every 15 d.

India: Shivgarh, 104,000 Cluster RCT 0.5 (0.4–0.6)b

Uttar Pradesh [37]a

Community health worker Facilitated initial community meetings.

Facilitated monthly community folk song meetings.

Facilitated monthly newborn care meetings with

stakeholders and community volunteers.

Identified pregnancies 3-monthly door-to-door.

Made 2 antenatal home visits.

Made 2 postnatal home visits.

Advised on care seeking

Supervisor Supported community health workers.

Community volunteer Supported home visits and community meetings.

Community role model Supported home visits and community meetings.

India: Barabanki & Unnao 45,000 Single control No effect

districts, Uttar Pradesh [61]

Auxiliary nurse midwife Registered pregnancies.

Made 3 antenatal home visits.

Conducted deliveries.

Made postnatal home visit.

PLoS Medicine | www.plosmedicine.org 4 April 2010 | Volume 7 | Issue 4 | e1000246

Table 1. Cont.

Population Evaluation Neonatal Mortality Rate

Who Did the Intervention? What Did They Do? Involved Design Effect: Odds Ratio (95% CI)

Integrated Child Development Recruited community volunteers.

Services worker

Registered pregnancies.

Made 3 antenatal home visits.

Made postnatal home visit.

Gave food supplements.

Community volunteer Made 3 antenatal home visits.

Made postnatal home visit.

Traditional birth attendant Conducted deliveries.

Nepal: Makwanpur district 170,000 Cluster RCT 0.7 (0.5–0.9)

[32]

Community facilitator Activated and facilitated monthly community

women’s groups.

Supervisor Supported facilitators.

Pakistan: Larkana district, 1,300,000 Cluster RCT 0.7 (0.6–0.8)

Sindh [50]

Traditional birth attendant Made 3 antenatal home visits.

Registered pregnant women with lady health worker.

Used delivery kits.

Lady health worker Supported traditional birth attendant.

Enrolled and followed up pregnancies.

Recorded outcomes.

Obstetrician Trained traditional birth attendants.

Ran 8 outreach clinics in 6 mo.

Pakistan: Hala & Matiari 139,000 Cluster RCT 0.7 (0.6–0.9)c

subdistricts, Sindh [39] (pilot)

Lady health worker Conducted community group education.

Identified pregnancies.

Provided basic antenatal care.

Made 2 antenatal home visits.

Made 5 postnatal home visits.

Identified and managed danger signs.

Linked with traditional birth attendant.

Traditional birth attendant Gave basic newborn care.

Attended community group education.

Community volunteer Set up community health committees.

Emergency transport fund.

3 monthly community group education.

a

Intervention 2 added liquid crystal thermometry by community health workers.

b

Rate ratio.

c

Comparison was pre-post intervention, not intervention-control.

CI, confidence interval; RCT, randomised controlled trial.

doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000246.t001

included curative care [35]. Strategies Health Workers, TBAs, and community underway in South and Southeast Asia

were also implemented by different cadres volunteers. (Bangladesh, India, Nepal, Pakistan, and

of workers. The Shivgarh strategy in- Most of the programs showed improve- Vietnam) and sub-Saharan Africa (Ethio-

volved community health workers re- ments in care: increased uptake of ante- pia, Ghana, Malawi, Mali, Mozambique,

munerated by the program and local natal care, some increase in institutional South Africa, Tanzania, and Uganda), and

volunteers [37]; the Projahnmo stra- delivery (although this was not a primary WHO and UNICEF now recommend

tegy involved NGO community health feature of any program), and better home visits in the first week of life by

workers and mobilisers [38]; and the performance on indicators of essential appropriately trained and supervised

Hala strategy involved government Lady newborn care. Further evaluations are health workers [42].

PLoS Medicine | www.plosmedicine.org 5 April 2010 | Volume 7 | Issue 4 | e1000246

Partnerships with Traditional Birth programs for newborn care. India’s Shiv- studies approximating complete packages;

Attendants garh trial made community mobilization current evidence was ‘‘a weak foundation

About 60 million infants are delivered integral to the intervention, while in for guiding effective implementation of

outside institutions annually, 23%–40% of Bangladesh’s Projahnmo trial, group ac- public health programmes addressing neo-

them by TBAs [19], women who deliver tivities were limited to visits made by natal health,’’ and the reviewers called for

babies in the community, with or without female community mobilisers every 4 mo. new effectiveness trials tailored to local

clinical training [43]. The idea of bringing The former trial showed an effect and the health needs and conducted at scale in

TBAs into the allopathic fold by upgrad- latter did not; integration and coverage developing countries [60].

ing their skills and connecting them with seem to be important.

health services has had a chequered Whether Workers Can Cope with the

history. Included in programs from the What Is Needed Outside South Asia Intensity Demanded

time of Alma Ata [44,45], subsequent All the major trials of community Programs have worked so far with

review led to the virtual abandonment of interventions for newborn survival have institutional cadres, community-based

TBA training, or at least a modification of so far been in South Asia. Their common- workers, and volunteers. In some cases

their role from care providers to link- alities are more striking than their differ- the community-based workers were a new

workers [46,47]. Recent reviews suggest ences: rural setting, female literacy at cadre [32,37,38,40,41], while in others

that traditional attendants could have a around 40%, home delivery rates over they were drawn from existing public

role in increasing newborn survival 80%, skilled birth attendance below 15%, sector cadres [39,50,61]. As Table 1

[45,48,49], and a controlled trial in rural and public sector health care systems shows, programs have usually involved

Pakistan found a 30% reduction in based on the primary health care model. more than one of these groups. Once a

neonatal mortality when they were linked Africa needs more attention, not least precedent is set—often a portfolio of

systematically with government communi- because the pattern of mortality may be activities—the options for less intensive

ty health workers and obstetric services different. Low birth weight—a key con- approaches become questionable. Several

[50]. There is also evidence that infants tributor to neonatal mortality in South of the model programs required at least

could be saved if TBAs had some skills in Asia—is much less common in African two home visits during pregnancy, a visit

managing birth asphyxia, for example countries, and post-neonatal mortality on the day of birth, and at least three

[51]. claims a greater share of under-5 deaths postnatal home visits [38,39,40,41]. It is

[56]. We hope that the operational not clear how much pruning models

research and trials underway in African would stand and still remain effective.

Five Things That We Need to countries, mentioned above, will answer Given the importance of the first days after

Know some of the questions about whether birth to neonatal mortality, perhaps drop-

The Correct Balance of Supply and strategies are both feasible and effective ping the later postnatal visits would not

Demand Intervention on another continent. compromise the outcomes [37,50,61]. In a

No attempt to address newborn deaths recent joint statement, WHO and UNI-

in the home will be successful if it does not How to Fit Components into CEF recommend a minimum of two visits,

reach the household and align with the Systems in the first 24 h and on the third day [42].

aspirations of family members [52–54]. It is possible to think about community Most programs involve an increased

How much of the agenda should be interventions in at least three ways: as a workload for community cadres and a

community-driven, and how much should series of activities that need to be delivered substantial contribution from volunteers.

be predefined by health sector inputs, is (‘‘package’’), as a framework for delivery While existing community-based health

still not clear. At one extreme, Nepal’s (‘‘system’’), or as a means of galvanising workers may achieve more job satisfaction

Makwanpur trial worked through wo- communities for change (‘‘mobilization’’). from clearly delineated activities and

men’s group discussions and the resulting The 16 recommended newborn care support, increased workloads may be

interventions were left to community practices are best seen as a package of challenging, particularly because of the

members to decide [32]. Maharashtra’s activities, and there have been recent requirement for extensive field activities.

SEARCH program involved a portfolio of attempts to refine its content: antenatal Haines and colleagues have described

interventions developed over several years care and birth preparedness, institutional problems in instituting focused tasks,

(training of TBAs, home visits by commu- delivery if possible, hygiene, early wiping adequate remuneration, training, and

nity health workers, identification of and wrapping of the infant (but delayed supervision in large-scale community

illness, and administration of oral and bathing), early and exclusive breastfeed- health-worker programs [62]. Less than

parenteral antibiotics). Perceptions of the ing, skin-to-skin contact between mother 15% of children born at home in five

most important intervention differ accord- and infant, and recognition and appropri- South Asian and sub-Saharan African

ing to the commentator. For some, the key ate treatment when danger signs appear countries were visited by a trained health

issue was the provision of injectable [57]. What is required is integration of worker within 3 d of birth. Speed of

antimicrobials by community-based work- family, community, health system out- reaction and mobility might also be

ers (perhaps responsible for 30%–40% of reach and institutional care, and also of obstacles: a community health worker,

the mortality reduction) [55]. For others, maternal, newborn, child, adolescent, and perhaps living in a different village, must

the essential transformation was due to the women’s health care into a systemic know about a woman’s pregnancy or be

longevity of the program and the commit- continuum [8,57–59]. Examining individ- informed of the birth and must then be

ment of its cadres, driven by deeply held ual components is not the same as willing and able to make repeated postna-

beliefs about community rights and action. evaluating the effects of delivering them tal visits to check for warning signs in

Both must have played a part, and within complex systems. A recent review mother and baby and to treat or refer

community group work has (rightly, we found no true effectiveness trials conduct- promptly. It is hard to know if this will

think) been included in all successful ed at scale in health systems and few happen, particularly since these activities

PLoS Medicine | www.plosmedicine.org 6 April 2010 | Volume 7 | Issue 4 | e1000246

Box. Five Things That We Need to Know The Next Stage

There is little doubt that community

1. The correct balance of supply and demand intervention interventions for newborn survival work in

2. What is needed outside South Asia principle. In our opinion, the key ques-

3. How to fit components into systems tions are now more about the medium

4. Whether workers can cope with the intensity demanded than the message: how effective simplified

5. Coverage at scale program designs might be, whether they

are relevant in African contexts, whether

they will be as effective as they appear, and

have been part of the augmented surveil- main challenge is to achieve the required how they could be rolled out and sus-

lance systems for some trials [37,38]. levels of community mobilization and tained. Research now needs to move from

Villages are heterogeneous, and vulnera- home visits by community-based workers. components to the operational realities of

ble marginalized groups may be less likely As with many public health interventions, systems [60,64]. Some major questions

to be visited at home when programs it is the least accessible groups (geograph- remain: the optimal population coverage

expand beyond trial models with more ically, socially, financially) who have the of community-based workers, since cover-

rigorous supervision. most problems and for whom outreach is age, we think, is crucial for success, and

most likely to be compromised if corners does require investment in community

Coverage at Scale are cut. Only 13% of women who deliver mobilization [65,66], the requirements

Successful model programs need to be at home in developing countries make a for selection of workers and their remu-

replicated, scaled up, and sustained. Al- postnatal care visit [63]. The first priority neration or compensation [41], and the

though cost is usually a prime concern in is for community newborn survival inter- right mix of existing and new cadres [12].

this sort of discussion, it has not so far been ventions to be included in public sector A particular challenge is how to integrate

a major obstacle. The interventions pro- health services. Here we face a tacit newborn and maternal survival interven-

posed are relatively inexpensive and could assumption that programs spearheaded tions [67]. For governments the choice of

be integrated with existing systems by NGOs will not be viable or scalable; approach should almost certainly focus on

[23,58]. It is health systems integration that the inertia of health systems will defining the roles and responsibilities of

that raises questions. Child survival is thwart efforts to build community linkages existing cadres in reaching out to women

unequivocally important, and several and generate enthusiasm and conscien- who deliver at home with an essential

countries have developed newborn care tiousness. Partnerships between the gov- newborn care package. This is not simply

policies. Government partners are in- ernment and third (nongovernment) sec- a matter of training health workers, since it

volved in operational research in Bangla- tors could help. The success of NGOs in is the marginalised and hard to reach who

desh, India, Indonesia, Nepal, Vietnam, Bangladesh, for example, has been un- are most at risk. Women’s groups repre-

Ethiopia, Malawi, Mali, Mozambique, precedented in the country, with nation- sent a valuable community resource that

Bolivia, and Guatemala (Saving Newborn wide reach for organisations such as already exists in many areas and may have

Lives/Save the Children, personal com- BRAC (www.brac.net) and private not- inbuilt sustainability. We see active in-

munication). In Nepal, the NGO Mother for-profit organisations such as the Dia- volvement of individuals and communities

and Infant Research Activities (MIRA) has betic Association of Bangladesh (www. as the key to achieving targeted coverage

embarked on a large trial in which NGO- dab-bd.org). Savings and credit initiatives of poor and marginalized families to bring

employed facilitators of women’s groups have led to the creation and sustenance of down neonatal mortality, and this is an

are replaced by existing female communi- opportunity for governments to facilitate

thousands of community groups across

ty health volunteers. SEARCH has sup- community mobilization in partnership

Asia, many of them run by and for

ported two pilot scale-up programs, one with civil society organisations.

women. Cross-system linkage has been

mediated through NGOs at seven sites in

difficult, and one of the central agendas is

Maharashtra (ANKUR) and one nested Acknowledgments

to evaluate the possibilities of collabora-

within the public health systems of five

tion between sectors so that health care We thank Joy Lawn and Steve Wall, both of

states (Indian Council of Medical Re-

systems are integrated rather than parallel. Save the Children/Saving Newborn Lives, for

search field trial). The findings of the

Shivgarh trial have been integrated into Clearly, government needs to be involved information on ongoing research, and Neena

Uttar Pradesh’s child survival program, in creating an enabling environment for Shah More and Glyn Alcock for opinions on the

such movements, perhaps only insofar as points raised in the article.

and home-based newborn care has been

included in both the Government of endorsement, but preferably through col-

India’s Reproductive and Child Health laboration and policy. For example, Indi- Author Contributions

(RCH-II) strategy and the Integrated a’s National Rural Health Mission, which ICMJE criteria for authorship read and met:

Management of Newborn and Child will work through community-based Ac- NN PT AP AC DO. Wrote the first draft of the

Illness. credited Social Health Activists (ASHAs), paper: DO. Contributed to the writing of the

Putting aside the issues of the content of represents an opportunity for creative paper: NN PT AP AC DO. Coordinated

cross-sectoral partnership. development of the paper: DO.

programs and the continuum of care, the

References

1. Schuftan C (1990) The Child Survival Revolu- resource settings - are we delivering? BJOG 116 neonatal deaths: When? Where? Why? Lancet

tion: a critique. Fam Pract 7: 329–332. (Suppl 1): S49–S59. 365: 891–900.

2. Lawn J, Kerber K, Enweronu-Laryea C, 3. Lawn J, Cousens S, Zupan J, for the Lancet 4. Saving Newborn Lives (2001) State of the world’s

Bateman M (2009) Newborn survival in low Neonatal Survival Steering Team (2005) 4 million newborns. Washington DC: Save the Children.

PLoS Medicine | www.plosmedicine.org 7 April 2010 | Volume 7 | Issue 4 | e1000246

5. Darmstadt G, Lawn J, Costello A (2003) Advanc- 27. Korkor Ansah E, Narh-Bana S, Asiamah S, 43. Sibley L, Sipe T, Koblinsky M (2004) Does

ing the state of the world’s newborns. Bull World Dzordzordzi V, Biantey K, et al. (2009) Effect of traditional birth attendant training improve

Health Organ 81: 224–225. removing direct payment for health care on referral of women with obstetric complications:

6. NNF (2004) The state of India’s newborns. New utilisation and health outcomes in Ghanaian a review of the evidence. Soc Sci Med 59:

Delhi & Washington DC: National Neonatology children: a randomised controlled trial. PLoS 1757–1768.

Forum & Save The Children US. Med 6: e1000007. doi:10.1371/journal. 44. WHO (1992) Traditional birth attendants. a joint

7. UNICEF (2008) Countdown to 2015: tracking pmed.1000007. WHO/UNICEF/UNFPA statement. Geneva:

progress in maternal, newborn and child survival. 28. Lagarde M, Haines A, Palmer N (2007) Condi- World Health Organization, United Nations

New York: United Nations Children’s Fund. tional cash transfers for improving uptake of Children’s Fund, United Nations Fund for

8. UNICEF (2008) The state of the world’s children health interventions in low- and middle-income Populatino Activities.

2009: maternal and newborn health. New York: countries: a systematic review. JAMA 298: 45. Sibley LM, Sipe TA (2006) Transition to skilled

United Nations Children’s Fund. 1900–1910. birth attendance: is there a future role for trained

9. Kidney E, Winter HR, Khan KS, 29. Freire P (1995) Pedagogy of hope: reliving traditional birth attendants? J Health Popul Nutr

Gulmezoglu AM, Meads CA, et al. (2009) pedagogy of the oppressed. New York: Continu- 24: 472–478.

Systematic review of effect of community-level um International Publishing Group. 46. Maine D (1990) Safe motherhood programs:

interventions to reduce maternal mortality. BMC 30. Taylor CE (1995) E.H. Christopherson Lecture: options and issues. New York: Center for

Pregnancy Childbirth 9: 2. lessons for the United States from the worldwide Population and Family Health, Columbia

10. Budin P (1907) The nursling. The feeding and Child Survival Revolution. Pediatrics 96: University.

hygiene of premature & full-term infants. Trans- 342–346. 47. WHO (2004) Beyond the numbers. Reviewing

lation by WJ Maloney. London: The Caxton 31. Howard-Grabman L, Seoane G, Davenport C, maternal deaths and complications to make

Publishing Company. MotherCare and Save the Children (2002) The pregnancy safer. Geneva: Department of Repro-

11. WHO (1996) Essential newborn care. Report of a Warmi Project: a participatory approach to ductive Health and Research, World Health

technical working group (Trieste, 25–29 April improve maternal and neonatal health, an Organization.

1994). WH0/FRH/MSM/96.13. Geneva: World implementor’s manual. Westport: John Snow 48. Sibley L, Sipe T (2004) What can a meta-analysis

Health Organization, Division of Reproductive International, Mothercare Project, Save the tell us about traditional birth attendant training

Health (Technical Support). Children. and pregnancy outcomes? Midwifery 20: 51–60.

12. Bhutta Z, Darmstadt G, Hasan B, Haws R (2005) 32. Manandhar D, Osrin D, Shrestha B, Mesko N, 49. Sibley LM, Sipe TA, Brown CM, Diallo MM,

Community-based interventions for improving Morrison J, et al. (2004) Effect of a participatory McNatt K, et al. (2007) Traditional birth

perinatal and neonatal health outcomes in intervention with women’s groups on birth attendant training for improving health behav-

developing countries: a review of the evidence. outcomes in Nepal: cluster randomized controlled iours and pregnancy outcomes. Cochrane Data-

Pediatrics 115: 519–617. trial. Lancet 364: 970–979. base Syst Rev. CD005460 p.

13. Darmstadt G, Bhutta Z, Cousens S, Adam T, 33. Barnett S, Azad K, Barua S, Mridha M, Abrar M, 50. Jokhio A, Winter H, Cheng K (2005) An

Walker N, et al. (2005) Evidence-based, cost- et al. (2006) Maternal and newborn-care practices intervention involving traditional birth attendants

effective interventions: how many newborn babies during pregnancy, childbirth, and the postnatal and perinatal and maternal mortality in Pakistan.

can we save? Lancet 365: 977–988. period: a comparison in three rural districts in N Engl J Med 352: 2091–2099.

14. Macro International Inc (2009) MEASURE DHS Bangladesh. J Health Popul Nutr 24: 394–402. 51. Singhal N, Bhutta Z (2008) Newborn resuscita-

STATcompiler. CalvertonMD: ICF Macro. 34. Barnett S, Nair N, Tripathy P, Borghi J, Rath S, tion in resource-limited settings. Semin Fetal

15. Houweling T, Kunst A (2010) Socio-economic et al. (2008) A prospective key informant Neonatal Med 13: 432–439.

inequalities in childhood mortality in low and surveillance system to measure maternal mortality 52. Winch P, Alam M, Akther A, Afroz D, Ali N,

middle income countries: a review of the - findings from indigenous populations in Jhark- et al. (2005) Local understandings of vulnerability

international evidence. Br Med Bull 93: 7–26. hand and Orissa. BMC Pregnancy and Child- and protection during the neonatal period in

16. Lawn J, Lee A, Kinney M, Sibley L, Carlo W, birth 8. Sylhet district, Bangladesh: a qualitative study.

et al. (2009) Two million intrapartum-related 35. Rosato M, Mwansambo C, Kazembe P, Phiri T, Lancet 366: 478–485.

stillbirths and deaths: where, why, and what can Soko Q, et al. (2006) Women’s groups’ percep- 53. Neonatal Mortality Formative Research Working

be done? Int J Gynecol Obstet 107: S5–S19. tions of maternal health issues in rural Malawi. Group (2008) Developing community-based in-

17. Wall S, Lee A, Niermeyer S, English M, Lancet 368: 1180–1188. tervention strategies to save newborn lives: lessons

Keenan W, et al. (2009) Neonatal resuscitation 36. Shah More N, Bapat U, Das S, Patil S, Porel M, learned from formative research in five countries.

in low-resource settings: what, who, and how to et al. (2008) Cluster-randomised controlled trial of J Perinatol 28 Suppl 2: S2–S8.

overcome challenges to scale up? Int J Gynecol community mobilisation in Mumbai slums to 54. Waiswa P, Kemigisa M, Kiguli J, Naikoba S,

Obstet 107: S47–S64. improve care during pregnancy, delivery, post- Pariyo GW, et al. (2008) Acceptability of

18. Lee A, Lawn J, Cousens S, Kumar V, Osrin D, partum and for the newborn. Trials 9: 7. evidence-based neonatal care practices in rural

et al. (2009) Linking families and facilities for care 37. Kumar V, Mohanty S, Kumar A, Misra R, Uganda - implications for programming. BMC

at birth: what works to avert intrapartum-related Santosham M, et al. (2008) Effect of community- Pregnancy Childbirth 8: 21.

deaths? Int J Gynecol Obstet 107: S65–S88. based behaviour change management on neona- 55. Bang AT, Reddy HM, Deshmukh MD,

19. Darmstadt G, Lee A, Cousens S, Sibley L, tal mortality in Shivgarh, Uttar Pradesh, India: a Baitule SB, Bang RA (2005) Neonatal and infant

Bhutta Z, et al. (2009) 60 million non-facility cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet 372: mortality in the ten years (1993 to 2003) of the

births: who can deliver in community settings to 1151–1162. Gadchiroli field trial: effect of home-based

reduce intrapartum-related deaths? Int J Gynecol 38. Baqui AH, El-Arifeen S, Darmstadt GL, neonatal care. J Perinatol 25 Suppl 1: S92–S107.

Obstet 107: S89–S112. Ahmed S, Williams EK, et al. (2008) Effect of 56. Lawn J, Costello A, Mwansambo C, Osrin D

20. Lawn J, Kinney M, Lee A, Chopra M, Donnay F, community-based newborn-care intervention (2007) Countdown to 2015: will the Millennium

et al. (2009) Reducing intrapartum-related deaths package implemented through two service-deliv- Development Goal for child survival be met?

and disability: can the health system deliver? ery strategies in Sylhet district, Bangladesh: a Arch Dis Child 92: 551–556.

Int J Gynecol Obstet 107: S123–S142. cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet 371: 57. Kerber KJ, de Graft-Johnson JE, Bhutta ZA,

21. Carroli G, Rooney C, Villar J (2001) WHO 1936–1944. Okong P, Starrs A, et al. (2007) Continuum of

programme to map the best reproductive health 39. Bhutta ZA, Memon ZA, Soofi S, Salat MS, care for maternal, newborn, and child health:

practices: how effective is antenatal care in Cousens S, et al. (2008) Implementing communi- from slogan to service delivery. Lancet 370:

preventing maternal mortality and serious mor- ty-based perinatal care: results from a pilot study 1358–1369.

bidity? Paediatr Perinatal Epidemiol 15 (Suppl 1): in rural Pakistan. Bull World Health Organ 86: 58. Darmstadt GL, Walker N, Lawn JE, Bhutta ZA,

1–42. 452–459. Haws RA, et al. (2008) Saving newborn lives in

22. Jaddoe V (2009) Antenatal education pro- 40. Bang A, Bang R, Baitule S, Reddy M, Asia and Africa: cost and impact of phased scale-

grammes: do they work? Lancet 374: 863–864. Deshmukh M (1999) Effect of home-based up of interventions within the continuum of care.

23. Knippenberg R, Lawn J, Darmstadt G, neonatal care and management of sepsis on Health Policy Plan 23: 101–117.

Begkoyian G, Fogstad H, et al. (2005) Systematic neonatal mortality: field trial in rural India. 59. Bhutta Z, Ali S, Cousens S, Ali T, Haider B, et al.

scaling up of neonatal care in countries. Lancet Lancet 354: 1955–1961. (2008) Interventions to address maternal, new-

365: 1087–1098. 41. Bang AT, Bang RA, Reddy HM (2005) Home- born, and child survival: what difference can

24. Campbell O, Graham W (2006) Strategies for based neonatal care: summary and applications of integrated primary health care strategies make?

reducing maternal mortality: getting on with what the field trial in rural Gadchiroli, India (1993 to Lancet 372: 972–989.

works. Lancet 368: 1284–1299. 2003). J Perinatol 25 (Suppl 1): S108–S122. 60. Haws RA, Thomas AL, Bhutta ZA,

25. WHO (1996) Maternity waiting homes: a 42. WHO, UNICEF (2009) WHO/UNICEF Joint Darmstadt GL (2007) Impact of packaged

review of experiences. Geneva: World Health Statement: home visits for the newborn child: a interventions on neonatal health: a review of

Organization. strategy to improve survival. WHO/FCH/CAH/ the evidence. Health Policy Plan 22: 193–215.

26. Borghi J, Ensor T, Somanathan A, Lissner C, 09.02. Geneva and New York: World Health 61. Baqui A, Williams EK, Rosecrans AM,

Mills A (2006) Mobilising financial resources for Organization and United Nations Children’s Agrawal PK, Ahmed S, et al. (2008) Impact of

maternal health. Lancet 468: 1457–1465. Fund. an integrated nutrition and health programme on

PLoS Medicine | www.plosmedicine.org 8 April 2010 | Volume 7 | Issue 4 | e1000246

neonatal mortality in rural northern India. Bull 64. Costello A, Filippi V, Kubba T, Horton R (2007) maternal and newborn health services. Bull

World Health Organ 86: 796–804, A. Research challenges to improve maternal and World Health Organ 85: 256–263.

62. Haines A, Sanders D, Lehmann U, Rowe AK, child survival. Lancet 369: 1240–1243. 67. Hofmeyr G, Haws R, Bergstrom S, Lee A,

Lawn JE, et al. (2007) Achieving child survival 65. Bryce J, Terrerri N, Victora C, Mason E, Okong P, et al. (2009) Obstetric care in low-

goals: potential contribution of community health Daelmans B, et al. (2006) Countdown to 2015: resource settings: what, who, and how to

workers. Lancet 369: 2121–2131. tracking intervention coverage for child survival. overcome challenges to scale up? Int J Gynecol

63. Fort A, Kothari M, Abderrahim N (2006) Lancet 368: 1067–1076. Obstet 107: S21–S45.

Postpartum care: levels and determinants in 66. Johns B, Sigurbjornsdottir K, Fogstad H, Zupan J,

developing countries. Maryland: Macro Interna- Mathai M, et al. (2007) Estimated global

tional Inc. resources needed to attain universal coverage of

PLoS Medicine | www.plosmedicine.org 9 April 2010 | Volume 7 | Issue 4 | e1000246

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- CPC Practice Exam - Medical Coding Study GuideDocument9 pagesCPC Practice Exam - Medical Coding Study GuideAnonymous Stut0nqQ0% (2)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Saving FredDocument5 pagesSaving Fredapi-251124571No ratings yet

- Detailed Lesson Plan (Resistor Color Coding)Document11 pagesDetailed Lesson Plan (Resistor Color Coding)Jessa Bahi-an100% (3)

- Teaching ResumeDocument2 pagesTeaching Resumeapi-281819463No ratings yet

- Public Private Partnerships Booket-2018Document44 pagesPublic Private Partnerships Booket-2018Prabir Kumar ChatterjeeNo ratings yet

- SCDS, Draft PolicyDocument33 pagesSCDS, Draft PolicyPrabir Kumar ChatterjeeNo ratings yet

- Leprosy Policy BriefDocument4 pagesLeprosy Policy BriefPrabir Kumar ChatterjeeNo ratings yet

- Emvolio Pilot Strategy DocumentDocument34 pagesEmvolio Pilot Strategy DocumentPrabir Kumar ChatterjeeNo ratings yet

- BNSL 043 Block 4Document140 pagesBNSL 043 Block 4Prabir Kumar Chatterjee100% (3)

- OWH On CancerDocument24 pagesOWH On CancerPrabir Kumar ChatterjeeNo ratings yet

- Fulwari SpacesDocument44 pagesFulwari SpacesPrabir Kumar ChatterjeeNo ratings yet

- MLHP Design Issues Concept Note June 24 2018Document7 pagesMLHP Design Issues Concept Note June 24 2018Prabir Kumar Chatterjee100% (2)

- How To Collect HMIS Data For BlocksDocument4 pagesHow To Collect HMIS Data For BlocksPrabir Kumar ChatterjeeNo ratings yet

- TB - Policy Brief v2Document4 pagesTB - Policy Brief v2Prabir Kumar ChatterjeeNo ratings yet

- Final ANM Malaria Guideline-2014Document10 pagesFinal ANM Malaria Guideline-2014Prabir Kumar ChatterjeeNo ratings yet

- Orientation of MAS Members On JaundiceDocument2 pagesOrientation of MAS Members On JaundicePrabir Kumar ChatterjeeNo ratings yet

- VedantaDocument1 pageVedantaPrabir Kumar ChatterjeeNo ratings yet

- Operational Guidelines LMISDocument19 pagesOperational Guidelines LMISPrabir Kumar ChatterjeeNo ratings yet

- Medical CorporationDocument1 pageMedical CorporationPrabir Kumar ChatterjeeNo ratings yet

- Sickle Cell Screening 21 March 2018Document2 pagesSickle Cell Screening 21 March 2018Prabir Kumar ChatterjeeNo ratings yet

- Arc GIS Make A MapDocument11 pagesArc GIS Make A MapPrabir Kumar ChatterjeeNo ratings yet

- Vedanta HospitalDocument1 pageVedanta HospitalPrabir Kumar ChatterjeeNo ratings yet

- SELCO Health Workshop Concept and AgendaDocument2 pagesSELCO Health Workshop Concept and AgendaPrabir Kumar ChatterjeeNo ratings yet

- Upright GMS 1977Document17 pagesUpright GMS 1977Prabir Kumar ChatterjeeNo ratings yet

- Budget For One AMRIT ClinicDocument4 pagesBudget For One AMRIT ClinicPrabir Kumar ChatterjeeNo ratings yet

- Raigarh SummaryDocument30 pagesRaigarh SummaryPrabir Kumar ChatterjeeNo ratings yet

- Chhattisgarh Yuva015Document2 pagesChhattisgarh Yuva015Prabir Kumar ChatterjeeNo ratings yet

- 2 Reggie Lepcha GMS 1977Document1 page2 Reggie Lepcha GMS 1977Prabir Kumar ChatterjeeNo ratings yet

- CEEW CG HighlightsDocument4 pagesCEEW CG HighlightsPrabir Kumar ChatterjeeNo ratings yet

- Raigarh Report PDFDocument52 pagesRaigarh Report PDFPrabir Kumar ChatterjeeNo ratings yet

- NHM SpendingDocument8 pagesNHM SpendingPrabir Kumar ChatterjeeNo ratings yet

- Jip (P 3T?C - 3 Lajg: Uau Ik XK Hkiifi XytDocument1 pageJip (P 3T?C - 3 Lajg: Uau Ik XK Hkiifi XytPrabir Kumar ChatterjeeNo ratings yet

- Search of Gunda Dhur - 1910Document8 pagesSearch of Gunda Dhur - 1910Prabir Kumar ChatterjeeNo ratings yet

- Saharias and TBDocument20 pagesSaharias and TBPrabir Kumar ChatterjeeNo ratings yet

- Quarter 2 - Module 2 - Sampling Techniques in Qualitative Research DexterVFernandezDocument26 pagesQuarter 2 - Module 2 - Sampling Techniques in Qualitative Research DexterVFernandezDexter FernandezNo ratings yet

- Vedantu Chemistry Mock Test Paper 1 PDFDocument10 pagesVedantu Chemistry Mock Test Paper 1 PDFSannidhya RoyNo ratings yet

- Reques... and TANGDocument2 pagesReques... and TANGMansoor Ul Hassan SiddiquiNo ratings yet

- Comparing Grade 12 Students' Expectations and Reality of Work ImmersionDocument4 pagesComparing Grade 12 Students' Expectations and Reality of Work ImmersionTinNo ratings yet

- Window Into Chaos Cornelius Castoriadis PDFDocument1 pageWindow Into Chaos Cornelius Castoriadis PDFValentinaSchneiderNo ratings yet

- Learn Verbs in EnglishDocument6 pagesLearn Verbs in EnglishCharmagne BorraNo ratings yet

- Factors Affecting The Deterioration of Educational System in The PhilippinesDocument6 pagesFactors Affecting The Deterioration of Educational System in The PhilippinesJim Dandy Capaz100% (11)

- A Paraphrasing Game For Intermediate EFL Learners: by Aida Koçi McleodDocument4 pagesA Paraphrasing Game For Intermediate EFL Learners: by Aida Koçi McleodK28 Ngôn Ngữ AnhNo ratings yet

- 00000548c PDFDocument90 pages00000548c PDFlipNo ratings yet

- The Systematic Design of InstructionDocument5 pagesThe Systematic Design of InstructionDony ApriatamaNo ratings yet

- Senior BRAG SheetDocument7 pagesSenior BRAG SheetbclullabyNo ratings yet

- 6 8 Year Old Post Lesson PlanDocument2 pages6 8 Year Old Post Lesson Planapi-234949588No ratings yet

- The National Law Institute University: Kerwa Dam Road, BhopalDocument2 pagesThe National Law Institute University: Kerwa Dam Road, Bhopaladarsh singhNo ratings yet

- Pondicherry University Distance MBA Admission 2015Document2 pagesPondicherry University Distance MBA Admission 2015Sakshi SoodNo ratings yet

- Preserving Historic Buildings and MonumentsDocument261 pagesPreserving Historic Buildings and MonumentsYoungjk KimNo ratings yet

- Grade Sheet For Grade 10-ADocument2 pagesGrade Sheet For Grade 10-AEarl Bryant AbonitallaNo ratings yet

- Student Paper Template GuideDocument3 pagesStudent Paper Template GuideelleyashahariNo ratings yet

- Bridge Month Programme English (R2)_240402_205400Document17 pagesBridge Month Programme English (R2)_240402_205400shivamruni324No ratings yet

- MBTIDocument15 pagesMBTIlujdenica100% (1)

- Director Capital Project Management in Atlanta GA Resume Samuel DonovanDocument3 pagesDirector Capital Project Management in Atlanta GA Resume Samuel DonovanSamuelDonovanNo ratings yet

- A Thematic Literature Review On Industry-Practice Gaps in TVETDocument24 pagesA Thematic Literature Review On Industry-Practice Gaps in TVETBALQIS BINTI HUSSIN A18PP0022No ratings yet

- 3rd Quarter ToolkitDocument10 pages3rd Quarter ToolkitDimple BolotaoloNo ratings yet

- Lac Understanding ResponsesDocument20 pagesLac Understanding ResponsesSheila Jane Dela Pena-LasalaNo ratings yet

- Guthrie A History of Greek Philosophy AristotleDocument488 pagesGuthrie A History of Greek Philosophy AristotleLuiz Henrique Lopes100% (2)

- Authentic Assessment For English Language Learners: Nancy FooteDocument3 pagesAuthentic Assessment For English Language Learners: Nancy FooteBibiana LiewNo ratings yet