Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Mador 149

Uploaded by

Chris Buck0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

39 views4 pagesERNEST T. MADORE, JR. Was convicted of aggravated felonious sexual assault. On appeal, he argues that the Superior Court erred in denying his motion for a mistrial. The jury could have found the following relevant facts, We affirm.

Original Description:

Original Title

mador149

Copyright

© Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentERNEST T. MADORE, JR. Was convicted of aggravated felonious sexual assault. On appeal, he argues that the Superior Court erred in denying his motion for a mistrial. The jury could have found the following relevant facts, We affirm.

Copyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

39 views4 pagesMador 149

Uploaded by

Chris BuckERNEST T. MADORE, JR. Was convicted of aggravated felonious sexual assault. On appeal, he argues that the Superior Court erred in denying his motion for a mistrial. The jury could have found the following relevant facts, We affirm.

Copyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 4

Mador149

NOTICE: This opinion is subject to motions for rehearing under

Rule 22 as well as formal revision before publication in the New

Hampshire Reports. Readers are requested to notify the Reporter,

Supreme Court of New Hampshire, One Noble Drive, Concord, New

Hampshire 03301, of any editorial errors in order that

corrections may be made before the opinion goes to press. Errors

may be reported by E-mail at the following address:

reporter@courts.state.nh.us. Opinions are available on the

Internet by 9:00 a.m. on the morning of their release. The direct

address of the court's home page is:

http://www.courts.state.nh.us/supreme.

THE SUPREME COURT OF NEW HAMPSHIRE

___________________________

Belknap

No. 2002-790

THE STATE OF NEW HAMPSHIRE

v.

ERNEST T. MADORE, JR.

Argued: September 17, 2003

Opinion Issued: November 7, 2003

Peter W. Heed, attorney general (Jonathan V. Gallo,

assistant attorney general, on the brief and orally), for the

State.

Shuchman, Krause & Vogelman, P.L.L.C., of Exeter (Lawrence

A. Vogelman and Joel T. Shaw on the brief, and Mr. Shaw orally),

for the defendant.

BROCK, C.J. The defendant, Ernest T. Madore, Jr., was

convicted of aggravated felonious sexual assault following a jury

trial in Superior Court (Perkins, J.). See RSA 632-A:2, I(i)

(1996). On appeal, he argues that the superior court erred in

denying his motion for a mistrial, as well as his motion for

discovery of the victim's counseling records. We affirm.

The jury could have found the following relevant facts. On

October 18, 2001, the victim and her sister, Jennifer, went to a

local Laconia bar after work. Later that night, arrangements

were made for the victim to be driven home by the defendant.

After leaving the bar, the victim and the defendant drove to a

friend's house where they smoked marijuana. They subsequently

returned to the victim's apartment.

While at the apartment, the victim, feeling intoxicated and

sleepy, sat on one end of her couch, waiting for her sister to

come to the apartment and meet the defendant. The defendant sat

on the other end of the couch, drinking a beer and watching a

movie. When Jennifer arrived, she helped her sister upstairs

into her bedroom, laid her on the bed and covered her with

blankets. The victim was intoxicated and fell asleep quickly.

After helping her sister to bed, Jennifer returned

downstairs where the defendant remained on the couch, watching

television. Approximately twenty minutes later, Jennifer left

the apartment for the night, expecting that the defendant would

sleep on the victim's couch. He subsequently entered the

victim's bedroom and sexually assaulted her.

At trial, the victim testified concerning the details of the

Page 1

Mador149

assault. During direct examination, she stated that after having

gone to sleep, she was awakened. "I was at the bottom of my bed

on my back with a big shadow over my body touching my private

area." She testified that her legs were dangling over the

bottom of her bed, her pajama bottoms had been removed, and she

eventually crawled backwards toward the headboard to escape her

assailant. She then rolled onto her stomach to flee and began

holding onto the headboard. She testified that, at that point,

the defendant "couldn't get his area into mine," and instead

ejaculated onto her back. The defendant said, "I'm sorry . . .

. I hope you don't hate me for this." She screamed, and he then

grabbed his things and ran out of the apartment.

During cross-examination, defense counsel questioned the

victim concerning discrepancies between her testimony on direct

examination and statements she had made to police officers the

morning of the assault. Specifically, defense counsel asked,

"You didn't mention to [the police] being on your back with your

legs dangling over; did you?" She replied, "That was a memory

that came after counseling." Both parties were then given the

opportunity to conduct a voir dire examination of the victim

outside the presence of the jury to determine whether her

testimony was the result of a repressed memory.

Following voir dire, the defendant moved for a mistrial.

Defense counsel also requested discovery of the victim's

counseling records, stating, "I think given that that evidence

has come out, we're entitled to try and get counseling records.

I think we're entitled to a hearing if those records determine

something." The State objected, arguing that the defendant had

suffered no prejudice, and, therefore, no mistrial should be

granted. Moreover, the State argued that the mere fact that the

victim underwent counseling was insufficient to permit discovery

of those records. The court agreed, and denied both motions.

We begin with the defendant's claim that the trial court

erred in denying his motion for mistrial. The defendant argues

that the victim's answer on cross-examination - "That was a

memory that came after counseling" - constituted testimony

based upon repressed memory which, pursuant to State v.

Hungerford, 142 N.H. 110, 119 (1997), was admissible only

following a pretrial reliability hearing. The defendant contends

that the court's failure to afford him a Hungerford hearing

caused him irreparable injury, entitling him to a mistrial. We

disagree.

The basis for granting a mistrial is the existence of

circumstances which indicate that justice may not be done if the

trial continues to verdict. State v. Dupont, 149 N.H. 70, 80

(2003). To justify a mistrial, prejudicial testimony must be

more than inadmissible, it must constitute an irreparable

injustice that cannot be cured by jury instructions. Id. The

trial court is granted broad discretion to decide whether a

mistrial or other remedial action is necessary because it is in

the best position to measure prejudicial impact. Id. Absent an

unsustainable exercise of discretion, we will not overturn the

trial court's decision not to grant a mistrial. Id. Based on

the record before us, we cannot conclude that the trial court

engaged in an unsustainable exercise of discretion.

At the outset, we note that the defendant's underlying

assumption that the victim's testimony was inadmissible

misconstrues the requirements set forth in Hungerford. In

Hungerford, concerned about the influence of therapy on the

recovery of memory, we concluded that "testimony that relies on

memories which previously have been partially or fully repressed

must satisfy a pretrial reliability determination." Hungerford,

142 N.H. at 119, 123. That pretrial hearing examines the

Page 2

Mador149

reliability of such testimony, as well as the reliability of the

techniques used to facilitate the recovery of repressed memories.

See id. at 125-26. The existence of repressed memory, however,

is a necessary precursor to that hearing; only when repressed

memory exists is a hearing held to determine its reliability.

See id. at 118-19.

In the present case, following voir dire, the trial court

found that the victim's memory was not repressed. Although the

defendant accords little weight to this finding, we will uphold

the trial court's findings of fact unless unsupported by the

record or clearly erroneous. State v. Brunelle, 145 N.H. 656,

658 (2000). Moreover, "[w]e accord the trial court's rulings on

evidentiary matters considerable deference," Hungerford, 142

N.H. at 117. "A trial court is accorded broad discretion in

ruling on the admissibility of evidence, and we review the trial

court's ruling under the unsustainable exercise of discretion

standard." State v. Lamprey, 149 N.H. 364, 370 (2003) (citation

omitted). Based upon the record before us, we defer to the trial

court's finding and evidentiary ruling.

During voir dire, the victim explained that she had

"memories that [she] was not able to write on a piece of paper

15 minutes after leaving the hospital because [she] was so upset,

but there were no brand new memories." When specifically asked

whether she had the memory of her feet dangling over the bed when

she was taken to the police station following the assault, she

stated that, "I had the memory of him hovering over my body at

the end of the bed, yes." The victim further explained the

omissions in her statements to police, stating that she did not

recount all of the details of the incident, because she "didn't

have the time or the patience or the energy after six hours of

being reraped again at a . . . hospital." Based on this

testimony, we conclude that the trial court's finding that no

issue of repressed memory existed was amply supported by the

record. This finding, then, preempted any need for a reliability

hearing pursuant to Hungerford. Because the court's failure to

conduct a pretrial hearing did not render the victim's testimony

inadmissible, we conclude that the trial court did not err in

denying the defendant's motion for mistrial.

We now address the defendant's contention that the superior

court should have permitted discovery of the victim's counseling

records. He argues that at a minimum, the court should have

ordered in camera review of those records to determine whether

they contained any evidence of repressed or recovered memories

prior to denying his previous motion for a mistrial.

"We review a trial court's decisions on the management of

discovery . . . under an unsustainable exercise of discretion

standard." State v. Amirault, 149 N.H. 541, 543 (2003).

Satisfying this standard requires the defendant to "demonstrate

that the trial court's rulings were clearly untenable or

unreasonable to the prejudice of his case." Id. Although

"[t]he threshold showing necessary to trigger an in camera

review is not unduly high[,] [t]he defendant must meaningfully

articulate how the information sought is relevant and material to

his defense." State v. Graham, 142 N.H. 357, 363 (1997); see

also State v. Gagne, 136 N.H. 101, 105 (1992). "[A] plausible

theory of relevance and materiality sufficient to justify review

of the protected documents" must be offered. Graham, 142 N.H.

at 363. "At a minimum, a defendant must present some specific

concern, based on more than bare conjecture, that, in reasonable

probability, will be explained by the information sought." Id.

(quotation omitted). We conclude that the trial court's decision

in this case was a sustainable exercise of discretion.

At trial, defense counsel stated:

Page 3

Mador149

At this point, I mean, it appears as to -- from her

answers and from what she says during the cross and

the direct that she tells the Court today that she had

all of the memories regarding what happened that day

prior to going into counseling. I still at this point

think I'm entitled to a mistrial. I think the

defendant is entitled to a mistrial. I think her

statement was -- and I know she tried to explain it,

but I think the statement was clear before when I

asked her the question about -- um -- why she didn't

tell them this, and she said she didn't remember it

until she went to counseling.

I think given that that evidence has come out,

we're entitled to try and get counseling records. I

think we're entitled to a hearing if those records

determine something.

(Emphasis added.) Assuming without deciding that defense

counsel's argument satisfied the requirements of Graham and Gagne

by setting forth "some factual basis beyond the mere existence

of counseling records," State v. Hoag, 145 N.H. 47, 50 (2000),

we nevertheless uphold the trial court's refusal to grant in

camera review. The specific concern offered by the defendant -

that in camera review was needed to determine whether the

victim's memory was repressed - was rendered moot by the trial

court's ruling that the victim's memory was not repressed.

Having already made that determination, the trial court was left

with little reason to afford in camera review other than the

defendant's general assertion that he was entitled to counseling

records. See id. (to trigger in camera review, defendant must

assert factual basis beyond the mere existence of counseling

records); see also State v. Taylor, 139 N.H. 96, 98 (1994).

Therefore, we conclude that the trial court did not err in

denying the defendant's motion for discovery.

Affirmed.

BRODERICK, NADEAU, DALIANIS and DUGGAN, JJ., concurred.

Page 4

You might also like

- C C B J.D./M.B.A.: Hristopher - UckDocument2 pagesC C B J.D./M.B.A.: Hristopher - UckChris BuckNo ratings yet

- TownsendDocument10 pagesTownsendChris BuckNo ratings yet

- JK S RealtyDocument12 pagesJK S RealtyChris BuckNo ratings yet

- HollenbeckDocument14 pagesHollenbeckChris BuckNo ratings yet

- MoussaDocument19 pagesMoussaChris BuckNo ratings yet

- SchulzDocument9 pagesSchulzChris BuckNo ratings yet

- BondDocument7 pagesBondChris BuckNo ratings yet

- Om Ear ADocument12 pagesOm Ear AChris BuckNo ratings yet

- BallDocument6 pagesBallChris BuckNo ratings yet

- Great American InsuranceDocument9 pagesGreat American InsuranceChris BuckNo ratings yet

- Claus OnDocument12 pagesClaus OnChris BuckNo ratings yet

- LarocqueDocument6 pagesLarocqueChris BuckNo ratings yet

- Ba Kun Czy KDocument3 pagesBa Kun Czy KChris BuckNo ratings yet

- MooreDocument4 pagesMooreChris BuckNo ratings yet

- City ConcordDocument17 pagesCity ConcordChris BuckNo ratings yet

- MarchandDocument9 pagesMarchandChris BuckNo ratings yet

- NicholsonDocument4 pagesNicholsonChris BuckNo ratings yet

- Philip MorrisDocument8 pagesPhilip MorrisChris BuckNo ratings yet

- PoulinDocument5 pagesPoulinChris BuckNo ratings yet

- Barking DogDocument7 pagesBarking DogChris BuckNo ratings yet

- DaviesDocument6 pagesDaviesChris BuckNo ratings yet

- AspenDocument6 pagesAspenChris BuckNo ratings yet

- AtkinsonDocument8 pagesAtkinsonChris BuckNo ratings yet

- SugarhillDocument6 pagesSugarhillChris BuckNo ratings yet

- Al WardtDocument10 pagesAl WardtChris BuckNo ratings yet

- National GridDocument5 pagesNational GridChris BuckNo ratings yet

- Reporter@courts - State.nh - Us: The Record Supports The Following FactsDocument6 pagesReporter@courts - State.nh - Us: The Record Supports The Following FactsChris BuckNo ratings yet

- ReganDocument12 pagesReganChris BuckNo ratings yet

- Firefighters Wolfe BoroDocument8 pagesFirefighters Wolfe BoroChris BuckNo ratings yet

- WalbridgeDocument3 pagesWalbridgeChris BuckNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5783)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Slip Form ConstructionDocument10 pagesSlip Form ConstructionAkshay JangidNo ratings yet

- Ar2022 en wb1Document3 pagesAr2022 en wb1peach sehuneeNo ratings yet

- MkgandhiDocument220 pagesMkgandhiDebarpit TripathyNo ratings yet

- Omoluabi Perspectives To Value and Chara PDFDocument11 pagesOmoluabi Perspectives To Value and Chara PDFJuan Daniel Botero JaramilloNo ratings yet

- 1-C 2-D3-E4-A5-B6-E7-D8-A9-D10-BDocument36 pages1-C 2-D3-E4-A5-B6-E7-D8-A9-D10-BJewel Emerald100% (4)

- Annexure ADocument7 pagesAnnexure ABibhu PrasadNo ratings yet

- Use Case Template (Cockburn) PDFDocument8 pagesUse Case Template (Cockburn) PDFjulian pizarroNo ratings yet

- Jack Mierzejewski 04-09 A4Document7 pagesJack Mierzejewski 04-09 A4nine7tNo ratings yet

- Marcos v. Robredo Reaction PaperDocument1 pageMarcos v. Robredo Reaction PaperDaveKarlRamada-MaraonNo ratings yet

- Elements of Consideration: Consideration: Usually Defined As The Value Given in Return ForDocument8 pagesElements of Consideration: Consideration: Usually Defined As The Value Given in Return ForAngelicaNo ratings yet

- Peta in Business MathDocument2 pagesPeta in Business MathAshLeo FloridaNo ratings yet

- iOS E PDFDocument1 pageiOS E PDFMateo 19alNo ratings yet

- Display of Order of IC Constitution and Penal Consequences of Sexual HarassmentDocument1 pageDisplay of Order of IC Constitution and Penal Consequences of Sexual HarassmentDhananjayan GopinathanNo ratings yet

- SOP For Master of Business Administration: Eng. Thahar Ali SyedDocument1 pageSOP For Master of Business Administration: Eng. Thahar Ali Syedthahar ali syedNo ratings yet

- Toward Plurality in American Acupuncture 7Document10 pagesToward Plurality in American Acupuncture 7mamun31No ratings yet

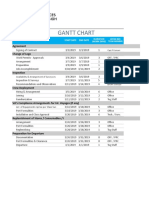

- Gantt Chart TemplateDocument3 pagesGantt Chart TemplateAamir SirohiNo ratings yet

- Bangla Book "Gibat" P2Document34 pagesBangla Book "Gibat" P2Banda Calcecian100% (3)

- IGNOU Hall Ticket December 2018 Term End ExamDocument1 pageIGNOU Hall Ticket December 2018 Term End ExamZishaan KhanNo ratings yet

- Russian SU-100 Tank Destroyer (30 CharactersDocument5 pagesRussian SU-100 Tank Destroyer (30 Charactersjason maiNo ratings yet

- Profit or Loss From Business: Schedule C (Form 1040 or 1040-SR) 09Document3 pagesProfit or Loss From Business: Schedule C (Form 1040 or 1040-SR) 09gary hays100% (1)

- Regio v. ComelecDocument3 pagesRegio v. ComelecHudson CeeNo ratings yet

- National University's Guide to Negligence PrinciplesDocument35 pagesNational University's Guide to Negligence PrinciplesSebin JamesNo ratings yet

- New Jersey V Tlo Research PaperDocument8 pagesNew Jersey V Tlo Research Paperfvg7vpte100% (1)

- Hlimkhawpui - 06.06.2021Document2 pagesHlimkhawpui - 06.06.2021JC LalthanfalaNo ratings yet

- Lec 2 IS - LMDocument42 pagesLec 2 IS - LMDương ThùyNo ratings yet

- Ob Ward Timeline of ActivitiesDocument2 pagesOb Ward Timeline of Activitiesjohncarlo ramosNo ratings yet

- Skanda Purana 05 (AITM)Document280 pagesSkanda Purana 05 (AITM)SubalNo ratings yet

- The Power of Habit by Charles DuhiggDocument5 pagesThe Power of Habit by Charles DuhiggNurul NajlaaNo ratings yet

- Case DigestsDocument31 pagesCase DigestsChristopher Jan DotimasNo ratings yet

- The Seven ValleysDocument17 pagesThe Seven ValleyswarnerNo ratings yet