Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Keefe. The Schizophrenia Cognition Rating Scale

Uploaded by

RosarioBengocheaSecoOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Keefe. The Schizophrenia Cognition Rating Scale

Uploaded by

RosarioBengocheaSecoCopyright:

Available Formats

Article

The Schizophrenia Cognition Rating Scale: An InterviewBased Assessment and Its Relationship to Cognition,

Real-World Functioning, and Functional Capacity

Richard S.E. Keefe, Ph.D.

Margaret Poe, M.A.

Trina M. Walker, R.N.

Joseph W. Kang, M.A.

Philip D. Harvey, Ph.D.

Objective: Interview-based measures of

cognition may serve as potential coprimary measures in clinical trials of cognitive-enhancing drugs for schizophrenia.

However, there is no such valid scale

available. Interviews of patients and their

clinicians are not valid in that they are unrelated to patients levels of cognitive impairment as assessed by cognitive performance tests. This study describes the

reliability and validity of a new interviewbase d ass ess ment of cognition, the

Schizophrenia Cognition Rating Scale

(SCoRS), that involves interviews with patients and informants.

Method: Sixty patients with schizophrenia were assessed with the SCoRS and

three potential validators of an interviewbased measure of cognition: cognitive performance, as measured by the Brief Assessment of Cognition in Schizophrenia (BACS);

real-world functioning, as measured by

the Independent Living Skills Inventory;

and functional capacity, as measured by

the University of California, San Diego, Performance-Based Skills Assessment (UPSA).

Results: The SCoRS global ratings were

significantly correlated with composite

scores of cognitive performance and functional capacity and with ratings of realworld functioning. Multiple regression

analyses suggested that SCoRS global ratings predicted unique variance in realworld functioning beyond that predicted

by the performance measures.

Conclusions: An interview-based measure of cognition that included informant

reports was related to cognitive performance as well as real-world functioning.

Interview-based measures of cognition,

such as the SCoRS, may be valid coprimary measures for clinical trials assessing

cognitive change and may also aid clinicians desiring to assess patients level of

cognitive impairment.

(Am J Psychiatry 2006; 163:426432)

he magnitude of neurocognitive deficits in schizophrenia ranges from moderate to severe (13), and most

aspects are strongly related to real-world functioning (4,

5). The standard assessments of neurocognition in schizophrenia are performance-based tests, and clinical trials

assessing the impact of new medicines or behavioral therapies on neurocognitive deficits in schizophrenia normally use performance tests as a primary outcome measure. Experts from an initiative established by the National

Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Measurement and

Treatment Research to Improve Cognition in Schizophrenia (MATRICS) project have recommended that the primary outcome measure for clinical trials of new medications to improve cognition should be a test battery

assessing cognition in seven cognitive domains: vigilance,

working memory, processing speed, verbal learning and

memory, visual learning and memory, reasoning and

problem solving, and social cognition.

However, from a clinical outcomes perspective, the sole

reliance on performance measures to assess cognition

and cognitive changes has limitations. Clinicians, family

426

ajp.psychiatryonline.org

members, and patients may not fully appreciate the relevance of improved performance on cognitive tests, and

these individuals are rarely qualified to measure cognitive

performance. In the absence of a framework for assessing

the beneficial aspects of these treatments, clinicians motivation to prescribe potential cognitive-enhancing interventions may be reduced, and the motivation of patients

and family members to improve treatment adherence will

be lessened. This issue has been of substantial importance

in other conditions, such as Alzheimers disease, where

cognition is a treatment target (6). Many clinicians would

like to be able to reliably assess the opinion of a patient or

a patients family or caregiver about the patients level of

neurocognitive deficits. For instance, clinicians often report that a patient appears cognitively more intact or more

alert with a new antipsychotic medication, yet they do not

have a method to measure this change. Such a scale would

enable a clinician to document evidence of improvement.

It also may serve as a screening instrument for research

studies aiming to identify patients with cognitive impairment or for clinicians making a determination as to

Am J Psychiatry 163:3, March 2006

KEEFE, POE, WALKER, ET AL.

whether medication specific for cognitive improvement is

warranted. Finally, many clinical psychiatrists may view

cognition as outside of their expertise because they do not

have an adequate tool to measure it. Such rating methods

may increase the extent to which clinicians consider neurocognitive deficits as targets of their treatment strategies.

Such a measure is also likely to be useful for clinical trials. The current position of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is that improvement on cognitive tests

will not be a sufficient criterion for accepting treatment

response with a potentially neurocognition-enhancing

drug. Previous FDA decisions have reflected the view that

cognitive performance changes need to be accompanied

by additional changes that have relevance for clinicians

and consumers, referred to as face validity. The Division of

Neuropharmacological Drug Products at the FDA has previously required additional outcomes beyond performance measures in clinical trials for the treatment of cognitive impairment in Alzheimers disease (7). Thus, it is

likely that any clinical trial of cognitive improvement in

schizophrenia will require a so-called coprimary measure

in addition to cognitive performance. Furthermore, while

eventual changes in real-world functioning (e.g., employment, independence in residential status) are the main

goal of any treatment directed at cognitive enhancement,

these changes may occur too slowly to be detected during

the course of a typical clinical trial of relatively short duration or may be influenced by outside factors, such as financial disincentives (8, 9).

Panel members from an FDA NIMH MATRICS workshop

on Clinical Trial Designs for Neurocognitive Drugs for

Schizophrenia suggested two potential types of assessment techniques for consideration as coprimary measures: functional capacity and interview-based assessment

of cognition. This panel also suggested that the validity of

these measures should be supported by good test-retest reliability, demonstrated associations with cognitive performance measures, and demonstrated associations with

real-world functioning (10) (www.matrics.ucla.edu).

Previous studies of interview-based assessments of cognitive function in patients with schizophrenia have shown

either nonsignificant or small correlations with cognitive

performance (1114). However, with the exception of the

Stip et al. (14) study, these studies have not used a scale

that was specifically designed to address the cognitive deficits of schizophrenia. In addition, these studies have relied upon patients self-reports or clinicians impression of

patients cognitive deficits. None has included informant

reports of patients cognitive function. It is possible that a

report from an individual who sees the patient regularly is

required to obtain an accurate view of the patients level of

cognitive functioning.

The current study describes the characteristics of a new

interview-based assessment of cognition administered to

patients and their informants, the Schizophrenia Cognition Rating Scale (SCoRS), and the extent to which it meets

Am J Psychiatry 163:3, March 2006

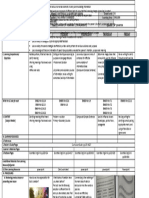

TABLE 1. Demographic Characteristics of Patients With

Schizophrenia

Characteristic

Age (years)

Education (years)

Mothers education (years)

Fathers education (years)

Wide-Range Achievement Test,

3rd Ed. reading test score

N

60

60

44

34

Mean

35.07

11.68

13.02

12.26

SD

9.74

2.06

2.65

3.49

56

44.95

7.59

the criteria for validity described by the FDA NIMH MATRICS panel. Although the test-retest reliability of the measure will be addressed in another study investigating the

longitudinal use of the SCoRS, the current study tested the

internal consistency and interrater reliability of the SCoRS

and established the extent to which it correlated crosssectionally with cognitive performance measures as assessed by a brief cognitive battery, the Brief Assessment of

Cognition in Schizophrenia (BACS) (15) and a clinical rating scale measure of real-world functioning, the Independent Living Skills Inventory (ILSI) (16). This study also included a measure of performance-based assessment of

functional capacity, the University of California, San Diego, Performance-Based Skills Assessment (UPSA) (17),

enabling a determination of the relationship between the

two types of measures under consideration by the FDA as

coprimary measures: interview-based assessments and

functional capacity assessments.

Method

Patients

Sixty patients with DSM-IV schizophrenia were assessed with a

battery of cognitive and functional measures, including the

SCoRS. One patient dropped out of the study before sufficient

data could be collected, and two additional patients did not complete the performance-based assessment of functional skills. The

demographic characteristics of the patient group are described in

Table 1. Forty-seven (78%) of the patients who provided data were

men. All patients were receiving antipsychotic medications. Eight

patients were receiving monotherapy with olanzapine, seven with

risperidone, 10 with aripiprazole, six with clozapine, three with

quetiapine, one with haloperidol, one with diflunisal, and 11 were

receiving antipsychotic medication as part of a blind study of antipsychotic treatments. Thirteen patients were being treated with

two antipsychotic medications. The majority of patients in this

study (N=55) were inpatients in a rehabilitation center at John

Umstead Hospital, during which they received ongoing behavioral treatment, such as occupational therapy, recreational therapy, group therapy that focused on activities of daily living, coping skills, household management, and substance abuse

counseling. Patients in this setting were required to have stable

symptoms without acute exacerbation. An additional five patients were included in the study who had recently been admitted

to an inpatient treatment facility at John Umstead Hospital. All

procedures were approved by the Human Subjects Committees of

Duke University Medical Center and John Umstead Hospital. The

patients were assessed for competence to provide informed consent. If they were competent, the study was explained to them,

and they were asked to participate and provide informed consent.

A separate report on the validity of neurocognitive tests has been

published from the group described in this study (18).

ajp.psychiatryonline.org

427

SCHIZOPHRENIA COGNITION RATING SCALE

Part 1: SCoRS

Item Generation

The SCoRS is an 18-item interview-based assessment of

cognitive deficits and the degree to which they affect dayto-day functioning. A global rating is also generated. Some

of the items for the scale were developed based upon the

content included in the Brief Cognitive Scale (19) for assessing patients with dementia and mild cognitive impairment. These items were modified, and additional items

were developed by the studys principal investigator

(R.S.E.K.), a masters-level psychologist (M.P.), a research

assistant with 5 years of experience with patients with

schizophrenia (T.M.W.), and a research assistant with 1

year of experience giving cognitive assessments to patients with schizophrenia (J.W.K.). The items were developed to assess the cognitive domains of attention, memory, reasoning and problem solving, working memory,

language production, and motor skills. These areas were

chosen because of the severity of impairment of these domains in many patients with schizophrenia and the demonstrated relationship of these areas of cognitive deficit to

impairments in aspects of functional outcome (4, 5). The

initial item pool was used in a pilot study on five patients

to obtain information regarding the usefulness of the

items and the anchor points. After these ratings, modifications were made, and the formal protocol was begun. The

data from those five pilot patients are not included in this

report.

Two examples of items from the SCoRS are, Do you

have difficulty with remembering names of people you

know? and Do you have difficulty following a TV show?

Each item is rated on a 4-point scale. Higher ratings reflect a greater degree of impairment. It is possible to make

a rating of n/a for not applicable (e.g., if the patient is

illiterate, items related to reading are rated n/a). Each

item has anchor points for all levels of the 4-point scale.

The anchor points for each item focus on the degree of impairment and the degree to which the deficit impairs dayto-day functioning. Interviewers considered cognitive deficits only and did their best to rule out noncognitive

sources of the deficits. For example, a patient may have

had severe difficulty managing money because he never

learned how to count money, which would suggest that

the limitation was related to level of education and not

cognitive impairment.

Complete administration of the SCoRS included two

separate sources of information that generated three different ratings: an interview with the patient, an interview

with an informant of the patient (family member, friend,

social worker, etc.), and a rating by the interviewer who

administered the scale to the patient and informant. Informal time estimates suggest that each interview required an average of about 12 minutes of interview time

and 1 or 2 minutes of scoring time. The informant based

his or her responses on interaction with and knowledge of

428

ajp.psychiatryonline.org

the patient; we aimed to identify the informant as the person who had the most regular contact with the patient in

everyday situations. In this study, all of the informants

were staff members. The interviewers rating reflected a

combination of the two interviews incorporating the interviewers observations of the patient. The informant ratings were completed within 7 days of the administration of

the patient rating.

A global rating was determined by the patient, informant, and interviewer after the 18 items were rated. For

the patient and informant interviews, the global rating reflects the overall impression of the patients level of cognitive difficulty in the 18 areas of cognition assessed and is

rated 110. The interviewer global ratings were highly correlated with a mean of the 18 items (r=0.88, df=57,

p<0.001). The interviewer global ratings were more highly

correlated with the global ratings based upon the interview with the informant (r=0.81, df=57, p<0.001) than the

interview with the patient (r=0.24, df=57, p=0.07), suggesting that if information from a patient and informant was

discrepant, interviewers tended to favor the opinion of the

informant. Furthermore, multiple regression analyses

suggested that significant variance in interviewer global

ratings was accounted for by the informant global ratings

(R2=0.65, F=107.56, df=1, 57, p<0.001), but no additional

variance was accounted for by the patient global ratings

(R2 change=0.00, F=0.52, df=1, 57, n.s.).

Interrater Reliability

Two interviewers (M.P. and T.M.W.) participated in the

same interview of 11 patients. Intraclass correlations of the

relationship between the ratings generated by the two interviewers were calculated to assess the interrater reliability of the 18 SCoRS items. Thirteen of the 18 items had an

intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) of 1.00, indicating

absolute agreement between the two interviewers for all 11

patients. The ICCs for four of the other five items were

greater than 0.90, and the lowest ICC for an item (Do you

have difficulty walking as fast you would like?) was 0.81.

Internal Consistency

Internal consistency for the scale was calculated by using Cronbachs alpha coefficient, which was found to be

0.79. Examination of the contribution of the individual

items to the total scale scores indicated that there were no

items whose deletion would have improved the overall internal consistency of the scale by more than 0.01.

Part 2: Validity Assessments

In order to examine the validity of the SCoRS, the relationship of the SCoRS to measures of cognitive and functional outcome in schizophrenia was determined. These

assessments are described in the following paragraphs, as

are the analyses performed to determine the estimated validity of the SCoRS.

Am J Psychiatry 163:3, March 2006

KEEFE, POE, WALKER, ET AL.

TABLE 2. Pearson Correlations Among Measures Used to Test Patients With Schizophrenia a

Pearson Correlation (r)

Measure

Brief Assessment of Cognition in Schizophrenia

composite score

Independent Living Skills Inventory total score

Performance-Based Skills Assessment total score

Schizophrenia Cognition Rating Scale global ratings

Patient

Informant

Independent

Living Skills

Inventory

Total Score

PerformanceBased Skills

Assessment

Total Score

0.420*

0.650**

0.406*

Schizophrenia Cognition Rating Scale

Global Ratings

Patient

Informant

Interviewer

0.063

0.078

0.129

0.415*

0.460**

0.509**

0.540**

0.481**

0.525**

0.356*

0.235

0.808**

a N for all correlations was between 55 and 59.

*p<0.01. **p<0.001.

BACS

The BACS takes approximately 30 minutes and is devised for easy administration and scoring by nonpsychologists (15). It is specifically designed to measure treatment-related improvements and includes alternate forms.

The BACS has high test-retest reliability and is as sensitive

to cognitive dysfunction in schizophrenia as standard batteries requiring 2.5 hours of testing time (15). The battery

of tests in the BACS includes brief assessments of reasoning and problem solving, verbal fluency, attention, verbal

memory, working memory, and motor speed.

List Learning Test (verbal memory). Patients are presented with 15 words and then asked to recall as many as

possible. This procedure is repeated five times. The outcome measure is the total number of words recalled. There

are two alternate forms.

Digit Sequencing Task (working memory). Pa t i e n t s

are presented with clusters of numbers of increasing

length. They are asked to tell the experimenter the numbers in order, from lowest to highest. The trials are of increasing difficulty. The outcome measure is the total number of correct items.

Token Motor Task (motor speed). Patients are given

100 plastic tokens and asked to place them into a container

as quickly as possible for 60 seconds. The outcome measure is the total number of tokens placed in the container.

Category Instances Test (semantic fluency). Patients

are given 60 seconds to name as many words as possible

within the category of supermarket items. The outcome

measure is the total number of unique words generated.

Controlled Oral Word Association Test (letter fluency). In two separate trials, patients are given 60 seconds to generate as many words as possible that begin

with the letters F and S. The outcome measure is the total

number of unique words generated.

Tower of London Test (reasoning and problem solving). Patients look at two pictures simultaneously. Each

picture shows three different-colored balls arranged on

three pegs, with the balls in a unique arrangement in each

picture. The patients are told about the rules in the task

and are asked to provide the least number of times the

Am J Psychiatry 163:3, March 2006

balls in one picture would have to be moved to make the

arrangement of balls identical to that of the opposing picture. The outcome measure is the number of trials on

which the correct response is provided. There are two alternate forms.

Symbol Coding (attention and processing speed).

As quickly as possible, patients write numerals 19 as

matches to symbols on a response sheet for 90 seconds. The

outcome measure is the total number of correct responses.

Composite Score. A composite score is calculated by

comparing each patients performance on each measure to

the performance of a healthy comparison group (15). The

standardized z scores from each test are summed, and the

composite score is the z score of that sum. The composite

score has high test-retest reliability in patients with schizophrenia and healthy comparison subjects (ICC>0.80).

ILSI

The ILSI is a standard functional assessment instrument

measuring the extent to which individuals are able to

competently perform a broad range of skills important for

successful community living (16). The scale includes 89

items covering 11 subscales, including personal management, hygiene and grooming, clothing, basic skills (e.g.,

personal phone number), interpersonal skills, home

maintenance, money management, cooking, resource utilization, general occupational skills, and medication management. Data are obtained from an interview with the

patient who is asked to provide information about his or

her performance. Each of the items is rated according to

the extent to which an individual is able to perform a skill,

as well as the extent of assistance or guidance required.

There is strong internal consistency among the items of

this scale, with Cronbachs alpha coefficient equaling 0.82.

An overall score was created for the ILSI by calculating a

mean of all 11 subscales.

UPSA

The UPSA assesses the skills necessary for functioning

in the community by asking patients to perform relevant

tasks and rating their performance (17). Skills are assessed

in the following five areas: household chores, communicaajp.psychiatryonline.org

429

SCHIZOPHRENIA COGNITION RATING SCALE

tion, finance, transportation, and planning recreational

activities. As an example of a household chore task, patients are given a recipe for rice pudding and then asked to

prepare a written shopping list. They are presented with

an array of items in a mock grocery store (e.g., milk, vanilla, cereal, soup, rice, canned tuna, cigarettes, a can of

beer, crackers), asked to pick out the items that they would

need to prepare the pudding, and told to write down the

items that they would still need to buy. Points are given for

each correct item on the shopping list. Completion of

tasks in each of the five areas takes about 30 minutes. The

UPSA has been found to have excellent reliability, including good test-retest stability, and is highly sensitive to differences between patients with schizophrenia and healthy

comparison subjects (17). An overall score was calculated

for the UPSA by taking a mean of the scores in each area.

In order to keep knowledge of a patients cognitive performance from biasing SCoRS and ILSI ratings, the tester

who assessed cognitive performance with the BACS and

functional capacity with the UPSA was always a different

person from the interviewer who assessed cognition with

the SCoRS and real-world functioning with the ILSI. In addition, raters remained blind to the results of the measures

they did not administer.

Results

Pearson correlations were calculated between the

SCoRS global ratings and three external validators: measures of cognition (BACS), performance-based assessment of functioning (UPSA), and real-world assessment of

functioning (ILSI). The strongest correlations between the

SCoRS measures and the validators were with the interviewers global rating. For none of the validators did the

patient or informant global ratings account for significant

variance beyond that accounted for by the global interviewer rating. Therefore, all subsequent analyses will report only the relationships with interviewers global rating.

The SCoRS interviewer global rating was significantly correlated with the BACS composite score, the UPSA total

score, and the ILSI total score (Table 2).

Stepwise regression analyses were conducted to determine the unique variance in real-world functioning accounted for by BACS, UPSA, and SCoRS ratings. These analyses suggested that the SCoRS interviewer global rating

predicted unique variance in real-world functioning as

measured by the ILSI more than that predicted by the BACS

and UPSA. When the BACS and UPSA were entered as the

first step of a stepwise linear regression analysis predicting

ILSI scores, they accounted for a significant proportion of

the variance (R2=0.187; F=6.11, df=2, 53, p=0.007). In the

second step of the regression, the SCoRS accounted for significant additional variance in ILSI scores (R2 change=

0.077; F=5.41, df=1, 52, p=0.02). When the order of entry

into the regression equation was reversed, the SCoRS accounted for significant variance in ILSI scores as the first

430

ajp.psychiatryonline.org

step in the regression (R2=0.225; F=15.68, df=1, 54, p<0.001).

In the second step of the regression, the BACS and UPSA did

not account for significant additional variance beyond the

SCoRS (R2 change=0.039; F=1.37, df=2, 52, n.s.).

Discussion

An interview-based assessment of cognition, the SCoRS,

meets two of the criteria established by the FDA NIMH

MATRICS panel for coprimary outcome measures for cognitive enhancement trials in schizophrenia. SCoRS global

ratings were strongly correlated with cognitive performance, as measured by the BACS, and strongly correlated

with real-world functioning, as measured by the ILSI. The

third criterion for coprimary outcome measures, test-retest reliability, was not assessed in this cross-sectional

study but will be assessed in a longitudinal study. However, the SCoRS was shown in this study to have excellent

interrater reliability.

In contrast to the current study, previous studies have

not found a strong relationship between neurocognitive

performance and ratings of cognition (1114). However,

these studies have relied upon either self-report or clinician report of patients cognitive functions, and none have

incorporated data from both patients and informants into

ratings determined by a systematic set of queries posed

and then rated by an interviewer. The methodology of the

SCoRS involves an assessment of cognitive functioning

based upon the opinions of the patient and an informant

and an interviewers decisions about which source of information is more reliable for each item and the global rating.

The data from this study suggest that when the patients

and informants ratings were discrepant, an interviewer

was more likely to use the informants ratings when determining the global ratings. In fact, as in previous work, the

patients ratings did not account for significant variance

beyond the informants ratings for objective validators, including the cognitive performance score, functional capacity score, or real-world functioning score (1214).

These data suggest that a patient interview might not be

a necessary component of an interview-based assessment

of cognition. On the other hand, while an informant was

available for all of the patients in this study, these results

suggest that interview-based assessments for patients

who do not have someone who observes them regularly

might be missing crucial information. This dependence

upon informants is a weakness of the interview-based

methodology that will present challenges for the inclusion

of some schizophrenia patients in clinical trials. Current

work is under way to develop more extensive interviews

for patients who do not have available informants.

The SCoRS interviewer global ratings were strongly related to cognitive performance. This validity criterion is

clearly the most important in determining that the SCoRS

assesses behaviors that are related to cognition. Although

the methodologies involved in assessing cognition by inAm J Psychiatry 163:3, March 2006

KEEFE, POE, WALKER, ET AL.

terview (with the SCoRS) and by performance (with the

BACS) are very different and always involved different raters blind to the score on the other measure, there was considerable shared variance in these two outcome measures,

suggesting that a common element of cognition is being

measured. These data suggest that the SCoRS meets this

criterion for being a potentially useful coprimary measure

for clinical trials of potentially cognition-enhancing drugs

for patients with schizophrenia.

The importance of cognition in schizophrenia hinges on

its relationship to real-world functioning. The key validator of a cognitive scale is thus its relationship to a measure

of real-world functioning. In this study, the SCoRS interviewer global ratings were strongly related to independent

functioning, as measured by the ILSI. In fact, the correlation of the SCoRS with real-world functioning was stronger than the relationship of the cognitive performance

score (BACS) or a performance-based measure of functional capacity (UPSA) was with real-world functioning.

These performance measures did not account for additional variance in ILSI scores beyond the SCoRS. These

data indicate that the SCoRS measures the aspects of cognition that are indeed relevant for real-world functioning.

The higher correlations of real-world functioning with

the SCoRS than with performance-based measures may

be due in part to content similarity or method variance.

Some of the SCoRS items ask the informant to provide information about functional skills performance, whereas

the ILSI rates real-world outcome. This information was

collected from the same sources and focuses on the same

content. In contrast, the two performance measures do

not explicitly reference real-world outcomes; factors

jointly influencing performance, such as social or test-taking anxiety, may be operative. However, method variance

is unlikely to be the only explanation for the strength of

these correlations. In other studies, cognitive and functional skills performance have been found to be highly

correlated in patients with schizophrenia, whereas both of

these performance domains were essentially unrelated to

patient self-reports of quality of life or functional disability

(20). In contrast, the SCoRS ratings were well associated

with performance-based validation measures as well as

real-world outcomes, providing validation information

that crossed over method of data collection.

One of the weaknesses of the methodology of this study

was that all patients were living in a rehabilitation setting

in which their cognition-related behavior could be viewed

by staff members, who served as informants. Further, data

on the frequency of informant contact were not collected.

Treatment trials to test cognitive enhancement with new

compounds are likely to involve outpatients who have less

frequent contact with individuals who will serve as informants (10). These informants may produce less reliable

information that may be more easily biased by noncognitive factors, such as mood symptom changes. Thus, the reliability and validity assessments of the SCoRS reported in

Am J Psychiatry 163:3, March 2006

this study are likely to be higher than can be expected in a

typical cognitive enhancement clinical trial.

In sum, the SCoRS is a new interview-based assessment

of cognition designed to measure the severity of cognitive

deficits as viewed by patients, informants, and interviewers. The data from this study suggest that this instrument

is valid in that global ratings are strongly correlated with

cognitive performance, functional outcome, and functional capacity. While the test-retest reliability has not yet

been determined, the interrater reliability of the measure

is very high. Several features of the SCoRS procedure may

contribute to its greater validity compared to previous

scales; these features include systematic queries, use of informant reports, and ratings based on a distillation of all

sources of information. The SCoRS may serve as a potential coprimary measure for FDA trials of cognitive-enhancing medications in patients with schizophrenia. It

also may be useful for clinicians as a means of collecting

data about their patients neurocognitive deficits and may

thus increase the extent to which clinicians consider neurocognitive deficits as treatment targets.

Presented in part at the 43rd annual meeting of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology, San Juan, Puerto Rico, Dec. 12

16, 2004. Received Jan. 27, 2005; revision received April 15, 2005;

accepted April 25, 2005. From the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Duke University Medical Center; the Department

of Psychiatry, Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York; and the VA

Veterans Integrated Service Network 3 Mental Illness Research, Education, and Clinical Center, The Bronx, N.Y. Address correspondence

and reprint requests to the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral

Sciences, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC 27710;

richard.keefe@duke.edu (e-mail).

Supported by a grant to Dr. Keefe from Janssen Pharmaceutica.

The authors receive royalties for use of the Schizophrenia Cognition

Rating Scale and the Brief Assessment of Cognition in Schizophrenia.

The authors thank the study patients for their contributions and

the following members of the treatment and research staff at John

Umstead Hospital and Duke University Medical Center: Joseph P.

McEvoy, William H. Wilson, Thomas Guthrie, and Edward Eastman.

References

1. Saykin AJ, Gur RC, Gur RE, Mozley PD, Mozley LH, Resnick SM,

Kester DB, Stafiniak P: Neuropsychological function in schizophrenia: selective impairment in memory and learning. Arch

Gen Psychiatry 1991; 48:618624

2. Harvey PD, Keefe RSE: Cognitive impairment in schizophrenia

and implications of atypical neuroleptic treatment. CNS Spectr

1997; 2:111

3. Heinrichs RW, Zankanis KK: Neurocognitive deficit in schizophrenia: a quantitative review of the evidence. Neuropsychology 1998; 12:426444

4. Green MF: What are the functional consequences of neurocognitive deficits in schizophrenia? Am J Psychiatry 1996; 153:

321330

5. Green MF, Kern RS, Braff DL, Mintz J: Neurocognitive deficits

and functional outcome in schizophrenia: are we measuring

the right stuff? Schizophr Bull 2000; 26:119136

6. Nestor PJ, Sheltens P, Hodges JR: Advances in the early detection of Alzheimers disease. Nat Med 2004; 10:S34S41

7. Laughren T: A regulatory perspective on psychiatric syndromes

in Alzheimer disease. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2001; 9:340345

ajp.psychiatryonline.org

431

SCHIZOPHRENIA COGNITION RATING SCALE

8. Green MF, Nuechterlein KH, Gold JM, Barch D, Cohen J, Essock

S, Fenton WS, Frese F, Goldberg TE, Heaton RK, Keefe RSE, Kern

RS, Kraemer H, Stover E, Weinberger DR, Zalcman S, Marder

SR: Approaching a consensus cognitive battery for clinical trials

in schizophrenia: the NIMH-MATRICS Conference to select cognitive domains and test criteria. Biol Psychiatry 2004; 56:301

307

9. Rosenheck R, Leslie D, Keefe RSE, McEvoy J, Swartz M, Perkins

D, Stroup S, Hsaio J, Lieberman J: Barriers to employment for

people with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 2006; 162:411417

10. Buchanan RW, Davis M, Goff M, Green MF, Keefe RSE, Leon AC,

Nuechterlein KH, Laughren T, Levin R, Stover E, Fenton W,

Marder SR: A summary of the FDA-NIMH-MATRICS workshop

on clinical trial design for neurocognitive drugs for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 2005; 31:519

11. Moritz S, Ferahli S, Naber D: Memory and attention performance in psychiatric patients: lack of correspondence between clinician-rated and patient-rated functioning with neuropsychological test results. J Int Neuropsychol Soc 2004; 10:

623633

12. van den Bosch RJ, Rombouts RP: Causal mechanisms of subjective cognitive dysfunction in schizophrenic and depressed patients. J Nerv Ment Dis 1998; 186:364368

13. Harvey PD, Serper MR, White L, Parrella MJ, McGurk SR, Moriarty PJ, Bowie C, Vadhan N, Friedman J, Davis KL: The convergence of neuropsychological testing and clinical ratings of cognitive impairment in patients with schizophrenia. Compr

Psychiatry 2001; 42:306313

432

ajp.psychiatryonline.org

14. Stip E, Caron J, Renaud S, Pampoulova T, Lecomte Y: Exploring

cognitive complaints in schizophrenia: the Subjective Scale to

Investigate Cognition in Schizophrenia. Compr Psychiatry

2003; 44:331340

15. Keefe RSE, Goldberg TE, Harvey PD, Gold JM, Poe M, Coughenour L: The Brief Assessment of Cognition in Schizophrenia: reliability, sensitivity, and comparison with a standard neurocognitive battery. Schizophr Res 2004; 68:283297

16. Menditto AA, Wallace CJ, Liberman RP, VanderWal J, Jones NT,

Stuve P: Functional assessment of independent living skills.

Psychiatr Rehabilitation Skills 1999; 3:200219

17. Patterson TL, Goldman S, McKibbin CL, Hughs T, Jeste DV: UCSD

Performance-Based Skills Assessment: development of a new

measure of everyday functioning for severely mentally ill

adults. Schizophr Bull 2001; 27:235245

18. Keefe RSE, Poe M, Walker TM, Harvey PD: The relationship of

the Brief Assessment of Cognition in Schizophrenia (BACS) to

functional capacity and real-world functional outcome. J Exp

Clin Neuropsychol (in press)

19. Krishnan KKR, Levy RM, Wagner HR, Chen G, Gersing K, Doraiswamy PM: Informant-rated cognitive symptoms in normal

aging, mild cognitive impairment, and dementia: initial development of an informant-rated screen (Brief Cognitive Scale) for

mild cognitive impairment and dementia. Psychopharmacol

Bull 2001; 35:7988

20. McKibbin C, Patterson TL, Jeste DV: Assessing disability in older

patients with schizophrenia: results from the WHODAS-II. J

Nerv Ment Dis 2004; 192:405413

Am J Psychiatry 163:3, March 2006

You might also like

- Survey Questionnaire - Job PerformanceDocument2 pagesSurvey Questionnaire - Job Performanceapi-194241825100% (13)

- Balance Scorecard of Nestle: A Report OnDocument7 pagesBalance Scorecard of Nestle: A Report OnJayanta 10% (1)

- Daily Lesson Log Ucsp RevisedDocument53 pagesDaily Lesson Log Ucsp RevisedAngelica Orbizo83% (6)

- Reinventing OrganizationDocument379 pagesReinventing OrganizationАлина ЛовицкаяNo ratings yet

- My Principles in Life (Essay Sample) - Academic Writing BlogDocument3 pagesMy Principles in Life (Essay Sample) - Academic Writing BlogK wongNo ratings yet

- A Brief Cognitive Assessment Tool PDFDocument8 pagesA Brief Cognitive Assessment Tool PDFKaram Ali ShahNo ratings yet

- Relationship Between The Activities of Daily Living Questionnaire and The Montreal Cognitive AssessmentDocument4 pagesRelationship Between The Activities of Daily Living Questionnaire and The Montreal Cognitive AssessmentCristina SavaNo ratings yet

- The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale 1962Document14 pagesThe Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale 1962Diego Ariel Alarcón SeguelNo ratings yet

- Kavanagh 2014 Simplifying The Assessment of AntidDocument2 pagesKavanagh 2014 Simplifying The Assessment of AntidokNo ratings yet

- Screening For Cognitive Impairment in Older Adults - An Evidence Update For The U.S. Preventive Services Task ForceDocument6 pagesScreening For Cognitive Impairment in Older Adults - An Evidence Update For The U.S. Preventive Services Task ForceSrilatha GirishNo ratings yet

- Acta Neuro Scandinavica - 2018 - Mani - Efficacy of Group Cognitive Rehabilitation Therapy in Multiple SclerosisDocument9 pagesActa Neuro Scandinavica - 2018 - Mani - Efficacy of Group Cognitive Rehabilitation Therapy in Multiple Sclerosismadalena limaNo ratings yet

- BaixadosDocument14 pagesBaixadosLanna RegoNo ratings yet

- Name: Lauren Hoppe and Emily MatthewsDocument26 pagesName: Lauren Hoppe and Emily Matthewsapi-238703581No ratings yet

- Explanation of Evaluation Table/Review of The LiteratureDocument14 pagesExplanation of Evaluation Table/Review of The LiteratureTIMOTHY ADUNGANo ratings yet

- General Hospital Psychiatry: Review ArticleDocument10 pagesGeneral Hospital Psychiatry: Review Articlehevi_tarsumNo ratings yet

- GAD-7 (Analysis)Document6 pagesGAD-7 (Analysis)carolccy54No ratings yet

- A Brief Measure For Assessing Generalized Anxiety DisorderDocument6 pagesA Brief Measure For Assessing Generalized Anxiety Disorderchvr70No ratings yet

- Occupational Therapy and Mental Health 1Document18 pagesOccupational Therapy and Mental Health 1Roman -No ratings yet

- Development and Validation of The FSIQ-RMS A New PDocument14 pagesDevelopment and Validation of The FSIQ-RMS A New Psda asfNo ratings yet

- Neuropsychological AssessmentDocument5 pagesNeuropsychological Assessmenthiral sangoiNo ratings yet

- 10 1080@13854046 2019 1696409Document35 pages10 1080@13854046 2019 1696409AnaArantesNo ratings yet

- Validity of A Short Functioning Test (FAST) in Brazilian Cacilhas2009Document4 pagesValidity of A Short Functioning Test (FAST) in Brazilian Cacilhas2009Victor AndersonNo ratings yet

- Herrmann WM, Stephan K. Int Psychogeriatr. 1992 4 (1) :25-44.Document20 pagesHerrmann WM, Stephan K. Int Psychogeriatr. 1992 4 (1) :25-44.Ангелина СкоморохинаNo ratings yet

- Clinical Reasoning - Jones PDFDocument12 pagesClinical Reasoning - Jones PDFIsabelGuijarroMartinezNo ratings yet

- Clinical Reasoning 2Document10 pagesClinical Reasoning 2Phooi Yee LauNo ratings yet

- Article Critique JUNE 26, 2022Document7 pagesArticle Critique JUNE 26, 2022jessicaNo ratings yet

- Unit 8Document24 pagesUnit 8pooja singhNo ratings yet

- Benefits of Cognitive-Motor Intervention in MCI and Mild To Moderate Alzheimer DiseaseDocument6 pagesBenefits of Cognitive-Motor Intervention in MCI and Mild To Moderate Alzheimer DiseaseLaura Alvarez AbenzaNo ratings yet

- CGASDocument4 pagesCGASDinny Atin AmanahNo ratings yet

- Zanelloetal 2006Document15 pagesZanelloetal 2006jk rNo ratings yet

- Chapter 12 Systematic Review of Prognostic TestsDocument13 pagesChapter 12 Systematic Review of Prognostic TestsMuammar EmirNo ratings yet

- Assessing Validity and Reliability of GL E3932ec1Document14 pagesAssessing Validity and Reliability of GL E3932ec1Gracia BarimanNo ratings yet

- Sample Article CritiqueDocument7 pagesSample Article CritiquerebeccaNo ratings yet

- Spitzer, R. L. Et Al (2006) A Brief Measure For Assessing Generalized Anxiety Disorder - The GAD-7Document6 pagesSpitzer, R. L. Et Al (2006) A Brief Measure For Assessing Generalized Anxiety Disorder - The GAD-7Kristopher MacKenzie BrignardelloNo ratings yet

- Basic PDFDocument2 pagesBasic PDFAshilla ShafaNo ratings yet

- Performance Validity Testing in NeuropsychologyDocument7 pagesPerformance Validity Testing in Neuropsychologyeup_1983No ratings yet

- Escala Ansietat Parkinson (PAS)Document55 pagesEscala Ansietat Parkinson (PAS)Mar BatistaNo ratings yet

- Potential Pitfalls of Clinical Prediction Rules: EditorialDocument3 pagesPotential Pitfalls of Clinical Prediction Rules: EditorialMaximiliano LabraNo ratings yet

- Medical Cannabis For The Treatment of DementiaDocument24 pagesMedical Cannabis For The Treatment of DementiaLorina BoligNo ratings yet

- Tugas EpidemiologiDocument5 pagesTugas EpidemiologiGita SusantiNo ratings yet

- Predictors of Psych Intervention To Promote Health Behaviour Adherence in HF 2021Document14 pagesPredictors of Psych Intervention To Promote Health Behaviour Adherence in HF 2021Bob JoeNo ratings yet

- DF 10 PDFDocument7 pagesDF 10 PDFCarolina UrrutiaNo ratings yet

- Methodology NotesDocument2 pagesMethodology Notesadacanay2020No ratings yet

- HuntintingDocument8 pagesHuntintingJose Bryan GonzalezNo ratings yet

- Activities of Daily Living (ADLs) - NORMASDocument10 pagesActivities of Daily Living (ADLs) - NORMASCarlos Eduardo NorteNo ratings yet

- The Clinical Assessment Interview For Negative SymptomsDocument8 pagesThe Clinical Assessment Interview For Negative Symptomskj0203No ratings yet

- Clinical Global Impression-Severity Score As A Reliable Measure For Routine Evaluation of Remission in Schizophrenia and Schizoaffective DisordersDocument8 pagesClinical Global Impression-Severity Score As A Reliable Measure For Routine Evaluation of Remission in Schizophrenia and Schizoaffective DisordersSadia ShafaqueNo ratings yet

- Gordon Et Al., (2019) Efecct of Pulmonary Rehabilitation On Symptoms of Anxiety and Depression in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary DiseaseDocument12 pagesGordon Et Al., (2019) Efecct of Pulmonary Rehabilitation On Symptoms of Anxiety and Depression in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary DiseaseAna Flávia SordiNo ratings yet

- Centre For Addiction Mental Health - SkinnerDocument8 pagesCentre For Addiction Mental Health - SkinnerAmelia NewtonNo ratings yet

- Ahmad LutfiDocument7 pagesAhmad LutfiByArdieNo ratings yet

- AGURU - Annotated BibliographyDocument1 pageAGURU - Annotated BibliographyRuhika AguruNo ratings yet

- 0004 282X Anp 73 11 0929Document5 pages0004 282X Anp 73 11 0929Aleja ToPaNo ratings yet

- A Randomized Controlled Trial of A Computer-Based Physician Workstation in An Outpatient Setting: Implementation Barriers To Outcome EvaluationDocument9 pagesA Randomized Controlled Trial of A Computer-Based Physician Workstation in An Outpatient Setting: Implementation Barriers To Outcome EvaluationDith Rivelta CallahanthNo ratings yet

- Effect of Primacy Care InglésDocument2 pagesEffect of Primacy Care InglésRaul MartinezNo ratings yet

- Puntis Et Al 2014 Associations Between Continuity of Care and Patient Outcomes in Mental Health Care A Systematic ReviewDocument10 pagesPuntis Et Al 2014 Associations Between Continuity of Care and Patient Outcomes in Mental Health Care A Systematic ReviewbraispmNo ratings yet

- Pad Screening Draft Evidence ReviewDocument92 pagesPad Screening Draft Evidence ReviewHaryadi KurniawanNo ratings yet

- Alzheimer PicoDocument6 pagesAlzheimer PicoRaja Friska YulandaNo ratings yet

- Mini-COG Test PDFDocument5 pagesMini-COG Test PDFIntellibrainNo ratings yet

- Four ScoreDocument5 pagesFour ScoreBeny RiliantoNo ratings yet

- Tratamiento en APP 2013Document34 pagesTratamiento en APP 2013Mauricio EtchegarayNo ratings yet

- Captura de Tela 2023-04-15 À(s) 08.50.03Document13 pagesCaptura de Tela 2023-04-15 À(s) 08.50.03Daiana BündchenNo ratings yet

- A Systematic Review of Studies Comparing Diagnostic Clinical Prediction Rules With Clinical JudgmentDocument25 pagesA Systematic Review of Studies Comparing Diagnostic Clinical Prediction Rules With Clinical JudgmentCambriaChicoNo ratings yet

- Systematic Reviews and Met A Analysis Scientific Rationale and InterpretationDocument9 pagesSystematic Reviews and Met A Analysis Scientific Rationale and InterpretationIbn JesseNo ratings yet

- Dimensional PsychopathologyFrom EverandDimensional PsychopathologyMassimo BiondiNo ratings yet

- Clinical Research Associate - The Comprehensive Guide: Vanguard ProfessionalsFrom EverandClinical Research Associate - The Comprehensive Guide: Vanguard ProfessionalsNo ratings yet

- Maintenance Guide PDFDocument2 pagesMaintenance Guide PDFRosarioBengocheaSecoNo ratings yet

- Early Warning SignsDocument1 pageEarly Warning SignsRosarioBengocheaSecoNo ratings yet

- ConnectednessDocument13 pagesConnectednessRosarioBengocheaSeco100% (1)

- Activities For Assessing and Developing ReadinessDocument17 pagesActivities For Assessing and Developing ReadinessRosarioBengocheaSecoNo ratings yet

- ConnectednessDocument13 pagesConnectednessRosarioBengocheaSeco100% (1)

- Bell 2010Document8 pagesBell 2010RosarioBengocheaSecoNo ratings yet

- Vaskin 2009Document3 pagesVaskin 2009RosarioBengocheaSecoNo ratings yet

- Social Perception and Social Skill in SchizophreniaDocument12 pagesSocial Perception and Social Skill in SchizophreniaRosarioBengocheaSecoNo ratings yet

- Ziv 2011Document2 pagesZiv 2011RosarioBengocheaSecoNo ratings yet

- Psychiatry Research: Philip Brittain, Dominic H. Ffytche, Allison Mckendrick, Simon SurguladzeDocument6 pagesPsychiatry Research: Philip Brittain, Dominic H. Ffytche, Allison Mckendrick, Simon SurguladzeRosarioBengocheaSecoNo ratings yet

- Couture 2006Document20 pagesCouture 2006RosarioBengocheaSecoNo ratings yet

- Social Cognition in Schizophrenia, Part 2: 12-Month Stability and Prediction of Functional Outcome in First-Episode PatientsDocument8 pagesSocial Cognition in Schizophrenia, Part 2: 12-Month Stability and Prediction of Functional Outcome in First-Episode PatientsRosarioBengocheaSecoNo ratings yet

- Roberts 2009Document7 pagesRoberts 2009RosarioBengocheaSecoNo ratings yet

- Assessment Tasks: Criteria Level Level Descriptors (Ib Myp Published: Year 5) Task IndicatorsDocument4 pagesAssessment Tasks: Criteria Level Level Descriptors (Ib Myp Published: Year 5) Task Indicatorsapi-532894837No ratings yet

- Political DoctrinesDocument7 pagesPolitical DoctrinesJohn Allauigan MarayagNo ratings yet

- EquivoqueDocument13 pagesEquivoquevahnitejaNo ratings yet

- Categorical Interview Questions W.IDocument3 pagesCategorical Interview Questions W.ISalcedo, Angel Grace M.No ratings yet

- Ataf-Form-1-For - Arpan TeachersDocument46 pagesAtaf-Form-1-For - Arpan Teachersnelson100% (1)

- Tugas Tutorial 3 Bahasa InggrisDocument6 pagesTugas Tutorial 3 Bahasa Inggrisidruslaode.usn100% (3)

- Research and Practice (7 Ed.) 'Cengage, Australia, Victoria, Pp. 103-121Document18 pagesResearch and Practice (7 Ed.) 'Cengage, Australia, Victoria, Pp. 103-121api-471795964No ratings yet

- Question Types IELTS Writing Task 2Document4 pagesQuestion Types IELTS Writing Task 2Ust AlmioNo ratings yet

- Ctrstreadtechrepv01988i00430 OptDocument30 pagesCtrstreadtechrepv01988i00430 Optpamecha123No ratings yet

- NeoClassical Growth Theory PPTs 4th ChapterDocument18 pagesNeoClassical Growth Theory PPTs 4th ChapterJayesh Mahajan100% (1)

- John Archer, Barbara Lloyd - Sex and Gender-Cambridge University Press (2002)Document295 pagesJohn Archer, Barbara Lloyd - Sex and Gender-Cambridge University Press (2002)eka yuana n tNo ratings yet

- Emt501 Task 1 Action PlanDocument5 pagesEmt501 Task 1 Action Planapi-238497149No ratings yet

- Chapter 3 Preliminary Information Gathering and Problem DefinitionDocument15 pagesChapter 3 Preliminary Information Gathering and Problem Definitionnoor marliyahNo ratings yet

- Presentation Lesson PlanDocument4 pagesPresentation Lesson Planapi-306805807No ratings yet

- Kelsey Klein ResumeDocument1 pageKelsey Klein Resumeapi-354618527No ratings yet

- Lección 22 - How Well + IntensifiersDocument2 pagesLección 22 - How Well + IntensifiersLuis Antonio Mendoza HernándezNo ratings yet

- Brave New World Web QuestDocument3 pagesBrave New World Web QuestΑθηνουλα ΑθηναNo ratings yet

- Alcohol Is A Substance Found in Alcoholic Drinks, While Liquor Is A Name For These Drinks. ... NotDocument7 pagesAlcohol Is A Substance Found in Alcoholic Drinks, While Liquor Is A Name For These Drinks. ... NotGilbert BabolNo ratings yet

- GRADES 1 To 12 Daily Lesson Log: Write The LC Code For EachDocument1 pageGRADES 1 To 12 Daily Lesson Log: Write The LC Code For EachIrene Tayone GuangcoNo ratings yet

- Information SheetDocument1 pageInformation SheetCaoimhe OConnorNo ratings yet

- Referral System in IndiaDocument24 pagesReferral System in IndiaKailash Nagar100% (1)

- Proficiency Testing RequirementsDocument5 pagesProficiency Testing RequirementssanjaydgNo ratings yet

- 75 Takeaways From Expert Secrets BookDocument16 pages75 Takeaways From Expert Secrets BookIacob Ioan-Adrian80% (5)

- Jove Protocol 55872 Electroencephalographic Heart Rate Galvanic Skin Response AssessmentDocument9 pagesJove Protocol 55872 Electroencephalographic Heart Rate Galvanic Skin Response AssessmentZim ShahNo ratings yet

- Tcallp Reporting Late ChildhoodDocument25 pagesTcallp Reporting Late ChildhoodnamjxxnieNo ratings yet