Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Uploaded by

sabinaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Uploaded by

sabinaCopyright:

Available Formats

368 F Journal of Near Eastern Studies

to tablets CTA 36, he concludes that we are on very

solid ground in claiming that these four tablets were

intended by their author/scribe to represent a narrative

sequence, (part of) a continuous story about Balu, a

cycle in the traditional terminology (p. 66). On the

other hand, the status of CTA 1 and 2 is unclear because

of the poor state of preservation of the two texts. Based

on detailed comments on epigraphy and material, the

author concludes that the traditional obverse-reverse

orientation of both tablets (CTA 1 and 2) is to be inverted, a shifting around of the data that cannot but

have repercussions on interpretation.

The chapter closes with a question concerning The

Meaning and Function of the Baal Cycle, based on the

fact that there can be no doubt that these texts are

religious but it is equally certain that religion is politics. The importance of kingship and royal prerogatives

in the myth can only, one might think, indicate that the

myth had special meaning for human kings2 (p. 72).

Quite correctly, he also includes in the discussion the

stele known as Baal au foudre (Balu with a Thunderbolt). Even so, the question of the possible function

of these mythological texts in the daily life of ancient

Ugarit must remain open: the texts from Ugarit have

provided no direct evidence on the cultic use of the

poems recorded by Ilmilku ... Any firm decision on

the precise use of these stories ... must, therefore,

await further evidence from Ras Shamra or from a yet

undiscovered similar site (p. 75). The section closes

with comments concerning the importance of correctly

tracing the family ties present in these stories.

The aim of chapter 3, Literary Composition in the

Hebrew Bible: The View from Ugarit, is to illustrate the similarities that exist between the data from

Ugarit and the next principal literary corpus, that to

be found in the Hebrew Bible; the emphasis is on

their literary qualities (p. 79). The chapter is divided

into two main parts, Ugaritic and Hebrew Poetry

and Hebrew Poetry Contrasted with Ugaritic Poetry, each in turn with several subsections. For the

interested reader it may be useful to give here the list

of texts in Ugaritic and from the Hebrew Bible that

the author compares and comments on:

Ugaritic and Hebrew PoetryPoetic Structure:

CTA 2:iv:89, CTA 4:vi:1635, CTA 14:i:725, CTA

23:1, CTA 24:1, RS 24.252, RIH 98/02 // Ps. 82,

Ps. 92:10, Ps. 101:1, Ps. 104:33, Exod. 15:1, Judg.

5:3, Prov. 30:1819. Poetic Imagery: CTA 2:iv:23

27, CTA 4:vii:3144, 2532, CTA 16:vi:3234, CTA

17:v:48, RS 24.252:15; // Prov. 8:12, Amos 1:2,

2 Sam. 22:1415, Ps. 29, Ps. 82.

Hebrew Poetry Contrasted with Ugaritic PoetryPrayer: RS 24.266 // Ps. 142. Wisdom Poetry: CTA 17:i:2533 // Proverbs 31:1031. Love

Poetry: CTA 14:iii:142153 // Song 4:17, 5:1. Lament Poetry: CTA 5:vi:925, CTA 5:vi:306:i:10,

RS 25.460 // 2 Sam. 1:2527, Lamentations 1:1, 1:4,

4:11, Ezek. 32:23, 16, Jeremiah 12:1, Ps. 28:3, Job

3:2023. Poetry in the Prophetic Books: Isa. 5:17.

This work has been written by a renowned specialist

in the various areas comprising Ugaritic studies. Furthermore, he is the editor (together with Pierre Bordreuil) of most of the Ugaritic texts found in recent

decades. As a result, this book not only provides an

up-to-date account of the topics discussed, but is also a

valuable summary of Pardees own research in the field

of Ugaritic literature. Undoubtedly, the result will be

of great interest and usefulness to Ugaritologists and

biblical scholars, but equally so to specialists in neighboring areas. The book also works perfectly at another

level: as a general introduction to Ugarit, so that its

potential readership is even wider.3 It only remains for

us to congratulate the author for producing a work that

is both erudite andaccessible.

On this important question see also, more recently, G. del

Olmo Lete, Littrature et pouvoir royal Ougarit. Sens politique

de la littrature dOugarit, in tudes ougaritiques II, ed. Valrie

Matoan, Michel Al-Maqdissi and Yves Calvet. Ras Shamra-Ougarit

vol. XX (Paris, 2012), 24150.

3

In this respect, in our opinion, this work by Pardee is a worthy

complement to books such as those by Marguerite Yon, The City of

Ugarit at Tell Ras Shamra (Winona Lake, IN, 2006), and by Izak

Cornelius and Herbert Niehr, Gtter und Kulte in Ugarit. Kultur

und Religion einer nordsyrischen Knigsstadt in der Sptbronzezeit

(Mainz am Rhein, 2004).

Foreigners and Egyptians in the Late Egyptian Stories: Linguistic, Literary and Historical Perspectives. By Camilla Di Biase-Dyson. Probleme der gyptologie 32. Band. Leiden: Brill, 2013. Pp. xx + 488. $233 (cloth).

Reviewed by Nikolaos Lazaridis, California State University, Sacramento

Camilla Di Biase-Dyson, Junior Professor of Egyptology at the Georg-August Universitt in Gttingen, has produced a thorough linguistic and literary

examination of the portrayal of Egyptian and foreign

characters in a corpus of Late Egyptian narratives, consisting of the works The Doomed Prince, The Quarrel

This content downloaded from 156.208.017.231 on October 04, 2016 18:26:45 PM

All use subject to University of Chicago Press Terms and Conditions (http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c).

Book Reviews F369

of Apophis and Seqenenre, The Taking of Joppa, and

The Misfortunes of Wenamun. Essentially, her monograph, which is a modified version of her doctoral

dissertation, submitted to Macquarie University, is a

successful attempt at testing a new methodology on

an already well-known corpus of literary texts that

so far has been approached mainly in a formalist or a

historical manner. This new method follows the basic

principles of Michael Hallidays Systemic Functional

Linguistics (henceforth SFL), which the author combines with Stylistics and New Historicism (or Cultural Poetics). In other words, the author has chosen

mainly a linguistic approach that allows privileged

access to meaning (p. 2; see also the justification

of the choice of this specific method on pp. 7576)

on the basis of Hallidays elements of lexicogrammar (namely, field, tenor, and mode) and through

its connection to Stylistics, a type of literary analysis

that explores meaning-making in different genres of

writing. The results of this approach are then tested

against the relationship of literature with real-life

experience. However, instead of contributing to the

history-minded goals of Egyptology (in this case, that

is, to reconstruct and better understand the sociohistorical context of Egyptian culture), the author makes

it clear that the analysis is more interested in a texts

intentions behind choosing to refer or allude to a historical reality (p. 118). The authors approach is thus

a considerable improvement if compared to earlier

scholarly attempts, which utilized linguistic methods

and concepts, such as Michle Brozes book Mythe et

roman en gypte ancienne: Les aventures dHorus et

Seth dans le Papyrus Chester Beatty I (Louvain, 1996),

and Deborah Sweeneys work on the value of pragmatics in Egyptian literature (e.g., her article Gender

and Requests in New Kingdom Literature, in Sex

and Gender in Ancient Egypt: Don Your Wig for a

Joyful Hour, ed. C. Graves-Brown [Swansea, 2008],

191213), or which focused on reconstructing the

literary works contexts, such as Richard Parkinsons

book Poetry and Culture in Middle Kingdom Egypt:

A Dark Side to Perfection (London, 2002).

The application of this complex method to characterization in Egyptian narrative has multiple advantages. To name a few, firstly, it allows the author to

revisit and reconstruct the narrative grammar of Late

Egyptian stories. This results in a careful examination

of the uses of grammar, syntax, and vocabulary in these

works, which generates a number of intriguing observations on the authors ways of masterminding the

portrayal of and interactions between the characters.

So for instance, in the chapter on The Doomed Prince,

the analysis includes significant points on the use of

narrative forms, such as sm pw jr.n=f and the distinction between .n and wn.jn clauses (pp. 15254). In

another example from the same chapter, the author

introduces the notion of a characters grammatical

visibility, which to some extent can be employed as

a useful quantifiable method of determining a characters significance in a narrative (p. 121).

Secondly, the authors methodology encourages

close reading of the characters verbal interactions,

interpreting them as important specimens of social behavior. The best example illustrating the type of results

this close reading generates is the authors extensive

analysis of the verbal interactions between Wenamun

and Tjekerbaal, the two protagonists of The Misfortunes of Wenamun, in chapter 5. In this chapter the

author identifies, for instance, several occasions during

which Wenamuns sayings and actions produce irony

on multiple levels (p. 342) and examines the display

of antagonism between the two characters, which is

marked by subtle strategies, such as Tjekerbaals decision not to return Wenamuns salutation or participate

in Wenamuns condescending small talk (pp. 299 and

301, respectively).

Finally, the choice to use this method for analyzing the comparable portrayal of Egyptian and foreign

characters grants the author the opportunity to reconsider the question of how Egyptian literary authors

treated foreigners and foreign lands in their works

(which has been discussed on multiple occasions by

Antonio Loprieno, among other scholars). As a result,

the author makes a number of important new observations on this theme, such as the fact that in general,

foreign characters were not portrayed as very different from Egyptian ones and that the only differences

between the two groups of characters that were emphasized in these narratives concerned the characters

religious choices (p. 360). Or, the fact that although

in most cases the power games involved in the stories

plots favored Egyptian characters (as in the case of the

Rebel of Joppa in The Taking of Joppa, in whose case

the author argues that his anonymity was probably

a political strategy diminishing his status [p. 249]),

Apophis in The Dispute of Apophis and Seqenenre and

the foreign princess in The Doomed Prince were characters that displayed heroic traits.

In addition to the noted strengths of this study, one

must also mention the arduous annotated grammatical

analysis of the examined Late Egyptian stories, which

is presented line-by-line in the books four appendices.

This content downloaded from 156.208.017.231 on October 04, 2016 18:26:45 PM

All use subject to University of Chicago Press Terms and Conditions (http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c).

370 F Journal of Near Eastern Studies

This, certainly, demonstrates the thoroughness of the

authors study and reinforces the first positive effect of

the chosen approach mentioned above.

With regard to this books weaknesses, I have identified two that are worth mentioning and that (ironically) are associated with its style of presentation. The

first concerns the extensive usage of linguistic jargon

related to the application of the SFL methodology.

The very fact that the author spends one whole chapter

(chapter 2) on explaining the mechanics and main notions of SFL shows that this method is rather complex

and dense, and that the author rightly predicted that

the targeted readership with a background in Egyptology or Near Eastern Studies will need the authors

help in understanding a new (to these disciplines)

method and its jargon (this much resembles the case

of Gerald Moerss Fingierte Welte in der gyptischen

Literatur des 2. Jahrtausends v. Chr: Grenzberschreitung, Reisemotiv und Fiktionalitt [Leiden, 2001], a

monograph published in the same series). Thus, with

a few exceptions, the author does a good job defining

and explaining the jargon early on. The scholar-reader,

however, is required to pay close attention to this early

chapter and quickly familiarize herself with SFLs rules

and terminology before attempting to understand the

specifics of the succeeding analysis. In such cases, although the inclusion of unfamiliar theory and jargon

seems to be a necessary evil, I would also recommend

a glossary of extra-disciplinary terms at the end of the

book, in order to help the reader cope with the new

material and avoid undermining clarity.

The second noticeable weakness relates to the verbal explication of the SFL-based textual analysis of

the narratives. Specifically, occasionally in the course

of chapters 35 the author attempts to describe some

results of the works textual analysis in great detail.

This often seems unnecessary, as a table presenting

the results would suffice, and also since the author

does not make any new points on the basis of these

results and does not bring them up again in the conclusive sections; such is the case, for example, with

the ideational analysis of Djehuty (pp. 23436) or of

Herihor (p. 284). Such tedious verbal descriptions of

quantitative analysis are often features of published

doctoral dissertations. In such cases I recommend

a more thorough revision of a dissertations style of

presentation so that when it is turned into a book, its

analysis runs more smoothly and effectively guides the

readers attention towards the important results and

their interpretation.

Overall, Di Biase-Dysons monograph is an original

interdisciplinary examination of an exciting corpus of

ancient literary texts. One must highlight the significance of studies, such as Di Biase-Dysons, that successfully introduce new methodologies to disciplines

like Egyptology, whose identities have been traditionally distinguished by the geographically-defined materials they examine rather than their specific ways of

examining them. Such studies are thus most welcome,

as they expand Egyptologys spectrum of methodological options by fruitfully connecting it to other

disciplines tested methods and theories.

Sufism, Black and White: A Critical Edition of Kitb al-Bay wa-l-Sawd by Ab l-asan al-Srjn (d. ca.

470/1077). Edited by Bilal Orfali and Nada Saab. Islamic History and Civilization: Studies and Texts, Volume

94. Leiden: Brill, 2012. Pp. xii + 570. $196 (cloth).

Reviewed by Th. Emil Homerin, University of Rochester

The Kitb al-Bay wa-l-Sawd (The Book of Black

and White) is a substantial collection of Sufi sayings in Arabic compiled by Ab al-asan al-Srjn.

Though the exact dates of his life are, as yet, unknown, al-Srjn was reportedly a disciple of Amad

ibn Muammad ibn amzah al-f (d. 441/1049),

and al-Srjn is mentioned by several of his contemporaries, including al-Hujwr (d. ca. 470/1077), and

al-Anr al-Haraw (d. 481/1089), who stated that

al-Srjn oversaw religious endowments (awqf), including those for a Sufi monastery (rib), in the city

of Srjn in the province of Kirmn, in south-eastern

Iran. As Orfali and Saab further note in their detailed

introduction, al-Srjn appears to have compiled his

collection to assist those interested in the Sufi path,

as well as to refute critics of Sufism (Introduction,

pp. 111). Hence, the title, The Book of Black and

White, may refer to the black words written on white

paper that bear wisdom leading the mystical adept,

as well as the skeptical critic, from the darkness of

ignorance toward spiritual illumination (Introduction,

pp. 1116).

In terms of content, The Book of Black and White

clearly reflects the teachings of al-Junayd (d. 297/910)

This content downloaded from 156.208.017.231 on October 04, 2016 18:26:45 PM

All use subject to University of Chicago Press Terms and Conditions (http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c).

You might also like

- Artists and Painting in Ancient EgyptDocument12 pagesArtists and Painting in Ancient EgyptsabinaNo ratings yet

- Ancient Egyptian DeitiesDocument3 pagesAncient Egyptian DeitiessabinaNo ratings yet

- Ancient Egyptian Coffins - Low PDFDocument60 pagesAncient Egyptian Coffins - Low PDFsabinaNo ratings yet

- Sho ShankDocument20 pagesSho ShanksabinaNo ratings yet

- Women in Ancient EgyptDocument1 pageWomen in Ancient EgyptsabinaNo ratings yet

- Coffin of Shepeten-KhonsuDocument1 pageCoffin of Shepeten-KhonsusabinaNo ratings yet

- KarommaDocument1 pageKarommasabinaNo ratings yet

- The Reliefs of Tomb N. 27 at The Asasif PDFDocument7 pagesThe Reliefs of Tomb N. 27 at The Asasif PDFsabinaNo ratings yet

- Harwa TombsDocument12 pagesHarwa TombssabinaNo ratings yet

- Sheshonq IDocument1 pageSheshonq IsabinaNo ratings yet

- Van Siclen - CH., "Obelisk",in: Redford.D., (Ed.), The Oxford: Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, II (Cairo, 2001)Document1 pageVan Siclen - CH., "Obelisk",in: Redford.D., (Ed.), The Oxford: Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, II (Cairo, 2001)sabinaNo ratings yet

- Sheshonq IDocument1 pageSheshonq IsabinaNo ratings yet

- Referance Female Occupations in Ancient EgyptDocument1 pageReferance Female Occupations in Ancient EgyptsabinaNo ratings yet

- Creation Stories of The Ancient Near EastDocument11 pagesCreation Stories of The Ancient Near EastsabinaNo ratings yet

- The Status of Women inDocument8 pagesThe Status of Women insabinaNo ratings yet

- Mage of The Mummy of Meresamun in Its CoffinDocument1 pageMage of The Mummy of Meresamun in Its CoffinsabinaNo ratings yet

- Statue of AmenirdisDocument1 pageStatue of AmenirdissabinaNo ratings yet

- Women in Ancient EgyptDocument1 pageWomen in Ancient EgyptsabinaNo ratings yet

- Statue of AmenirdisDocument1 pageStatue of AmenirdissabinaNo ratings yet

- Bryn Mawr Classical Review 2002Document5 pagesBryn Mawr Classical Review 2002sabinaNo ratings yet

- KarommaDocument1 pageKarommasabinaNo ratings yet

- Bock Statue of HorDocument1 pageBock Statue of HorsabinaNo ratings yet

- Van Siclen - CH., "Obelisk",in: Redford.D., (Ed.), The Oxford: Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, II (Cairo, 2001)Document1 pageVan Siclen - CH., "Obelisk",in: Redford.D., (Ed.), The Oxford: Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, II (Cairo, 2001)sabinaNo ratings yet

- Libya and Egypt C. 1300-750 B.CDocument1 pageLibya and Egypt C. 1300-750 B.CsabinaNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5782)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- GX Boehringer Ingelheim Case StudyDocument1 pageGX Boehringer Ingelheim Case StudySomansh BansalNo ratings yet

- Entrance Examination Result of MBBS Program 2014Document36 pagesEntrance Examination Result of MBBS Program 2014Adina BatajuNo ratings yet

- Law of Contract NotesDocument112 pagesLaw of Contract NotesChris Sanders80% (5)

- March 2018 Highlights: Banco BICE Performance and Chilean EconomyDocument27 pagesMarch 2018 Highlights: Banco BICE Performance and Chilean EconomyDarío Guiñez ArenasNo ratings yet

- The Structure of ISO 27001Document11 pagesThe Structure of ISO 27001Mohammed Abdus Subhan100% (1)

- Pega Client Lifecycle ManagementDocument36 pagesPega Client Lifecycle ManagementVamsidhar Reddy DNo ratings yet

- Personal History Statement Instructions: ConfidentialDocument8 pagesPersonal History Statement Instructions: ConfidentialcgacNo ratings yet

- RCM Expenses List Under GSTDocument5 pagesRCM Expenses List Under GSTAnonymous O3P3qkNo ratings yet

- India and SEA Infra Startups - Lightspeed, Google and Github Report (8th Sept 2022)Document12 pagesIndia and SEA Infra Startups - Lightspeed, Google and Github Report (8th Sept 2022)Apurva ChamariaNo ratings yet

- InquestDocument5 pagesInquestclandestine2684No ratings yet

- Central Surety vs. C.N HodgesDocument11 pagesCentral Surety vs. C.N HodgesMirzi Olga Breech SilangNo ratings yet

- Wide Sargasso Sea-WikipediaDocument4 pagesWide Sargasso Sea-Wikipediafiyert tNo ratings yet

- NCSE English Language Arts 2014 P3Document13 pagesNCSE English Language Arts 2014 P3XxNight WolfxXNo ratings yet

- TheWire Apr03Document108 pagesTheWire Apr033 SR Welfare TeamNo ratings yet

- c2 Cases 3Document166 pagesc2 Cases 3Myooz MyoozNo ratings yet

- 六年级修辞01 Worksheet CroppedDocument5 pages六年级修辞01 Worksheet CroppedI am BearNo ratings yet

- Walk in Urgent Care ServicesDocument2 pagesWalk in Urgent Care ServicesMichel harryNo ratings yet

- Chapter 4Document12 pagesChapter 4norleen.sarmiento100% (2)

- Kenyon Frederic G., Books and Readers in Ancient Greece and Rome 1951Document80 pagesKenyon Frederic G., Books and Readers in Ancient Greece and Rome 1951kalliopi70100% (1)

- Introduction To The Field of Organizational BehaviourDocument32 pagesIntroduction To The Field of Organizational BehaviourSubharaman VenkitaNo ratings yet

- Baroque and Rococo Architecture (Art Ebook)Document136 pagesBaroque and Rococo Architecture (Art Ebook)DanielE.Dzansi100% (2)

- Serg's Products v. Pci Leasing-DigestDocument2 pagesSerg's Products v. Pci Leasing-Digesthermana990100% (2)

- The Last Day in The Life of Princess DianaDocument17 pagesThe Last Day in The Life of Princess DianaMyaW73150% (2)

- 59 PDFDocument33 pages59 PDFMariusCalinnNo ratings yet

- Y2022 SD en PDFDocument242 pagesY2022 SD en PDFMohamad HairidzNo ratings yet

- Comparative Rhetorical AnalysisDocument7 pagesComparative Rhetorical Analysisapi-308816815No ratings yet

- Assignment On Commercial BanksDocument15 pagesAssignment On Commercial BanksMukul Pratap SinghNo ratings yet

- Lv3.Unit 45Document7 pagesLv3.Unit 45amritessNo ratings yet

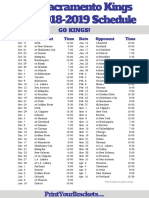

- Sacramento Kings 2018-19 Schedule GuideDocument1 pageSacramento Kings 2018-19 Schedule GuideMelchor BalolongNo ratings yet

- M136A1 AT4 Confined Space (AT4-CS)Document23 pagesM136A1 AT4 Confined Space (AT4-CS)rectangleangleNo ratings yet