Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Peptic Ulcer Disease Guidline Univ of Michigan Health System PDF

Uploaded by

syafiraOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Peptic Ulcer Disease Guidline Univ of Michigan Health System PDF

Uploaded by

syafiraCopyright:

Available Formats

University of Michigan

Health System

Guidelines for

Clinical Care

Peptic Ulcer Disease

Peptic Ulcer

Guideline Team

A. Mark Fendrick, M.D.

General Internal Medicine

Randall T. Forsch, M.D.

Family Medicine

R. Van Harrison, Ph.D.

Medical Education

Patient population: Adults less than 50 years of age

Objectives: (1) Implement a cost effective strategy incorporating testing for and eradication of

Helicobacter pylori (HP) in patients with suspected peptic ulcer disease (PUD). (2) Reduce ulcer

recurrence and prevent the overuse of chronic anti-secretory medications in PUD patients.

Key points

Clinical approach. Ulcers are caused by an infection of a bacterium known as Helicobacter

pylori or H. pylori. Eradication of HP infection alters the natural history of peptic ulcer disease.

Successful eradication reduces PUD recurrence rate from 90% to < 5% per year [A*]. PUD

generally does not recur in the successfully treated patient unless nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory

drug (NSAID) use is present.

Diagnosis. Economic analyses demonstrate a cost effectiveness advantage of non-invasive testing

and antibiotic therapy for HP in patients with symptoms suggestive of PUD when compared to

immediate endoscopy. [evidence: C*] Testing for active HP infection (stool antigen or urea breath

testing) is more appropriate than serology testing in areas with low prevalence of active HP

infection to reduce unnecessary treatment of individuals without active HP infection.

Treatment. H. pylori eradication therapy consists of antibiotics and anti-secretory drugs. [A*]

Long-term acid inhibition is inappropriate in the management of HP-related PUD in most

instances. [B*]

Follow-up. Referral to the gastroenterologist should occur for all patients with signs and

symptoms of complicated ulcer disease and for patients who fail initial therapy based on a noninvasive HP test. Persistent symptoms after 2 weeks of therapy suggest an alternative diagnosis.

James M. Scheiman, M.D.

Gastroenterology

Updated

May 2005

UMMC Guidelines

Oversight Team

Connie J. Standiford, MD

Lee A. Green, MD

R. Van Harrison, PhD

Literature Search Service

Taubman Medical Library

* Levels of evidence for the most significant recommendations

A=randomized controlled trials; B=controlled trials, no randomization; C=decision analysis; D=opinion of expert panel

Clinical Background

For more information call

GUIDES: 936-9771

Regents of the

University of Michigan

These guidelines should not

be construed as including

all proper methods of care

or excluding other

acceptable methods of care

reasonably directed to

obtaining the same results.

The ultimate judgment

regarding any specific

clinical procedure or

treatment must be made by

the physician in light of the

circumstances presented by

the patient.

Clinical Problem and

Current Dilemma

Incidence. In the United States there are

approximately 500,000 new cases and 4 million

recurrences of peptic ulcer disease (PUD) yearly.

The one-year point prevalence of PUD in the

U.S. is about 1.8%, with a lifetime prevalence of

8-14%. Estimated annual direct costs for PUD

are $3.3 billion, with additional indirect costs of

$6.2 billion.

Cost-effective new treatment. A National

Institute of Health Consensus Panel (1994)

recommended that all patients with Helicobacter

pylori (HP) infection and one of the following

diagnoses require eradication therapy with

antimicrobial agents in addition to anti-secretory

drugs.

1) newly documented ulcer

2) history of documented ulcer and ongoing

antisecretory therapy

3) history of complicated duodenal ulcer disease

An economic analysis has demonstrated the

benefit of initial non-invasive [nonendoscopic] testing for HP and antibiotic

therapy for those patients who test positive for

HP infection who were suspected to have

PUD. Endoscopy, the gold-standard, is not

recommended solely for the diagnosis for HP.

This initial non-invasive diagnostic approach

considers the risk-benefit tradeoff inherent in

overtreating those patients who are infected

with HP (or those with a false positive

serology) but do not have active ulcer disease.

Clinical studies are underway to evaluate these

estimates drawn from decision analysis.

(continued on page 3)

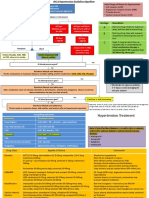

Figure 1. Peptic Ulcer Disease in Adults

Symptoms suggestive of

Peptic Ulcer Disease

(Table 1)

Ulcer complicated?

(Table 2)

Yes

No

No

Stop NSAID

Yes

On NSAID?

No

Symptoms resolve?

Previously treated

for H. pylori?

Yes

No

Select and perform noninvasive H. pylori test [C*]

(Table 3)

No further treatment

PUD unlikely. Consider

other Dx, e.g., nonulcer

dyspepsia, GERD

* Levels of Evidence:

A = randomized controlled trials

B = controlled trials, no randomization

C = observational trials

D = opinion of expert panel

Yes

H. pylori test

positive?

No

Yes

Prescribe H. pylori

eradication therapy [A*]

(Table 4)

Signs and symptoms

1-2 weeks post Rx?

Yes

Refer for further

evaluation

(gastroenterology)

No

No maintenance Rx

required

TABLE 1

Symptoms of

Peptic Ulcer

Gnawing or burning epigastric

pain

Pain relieved with food or

antacids

Pain that awakens at night or

between meals when

stomach is empty

(Heartburn as the predominant

symptom indicates GERD, not

PUD)

TABLE 2

Signs and Symptoms

of Complicated Ulcer

TABLE 3

H. pylori Tests

and Charges

GI bleeding (e.g., heme

positive stool, melena,

hematemesis, anemia)

Obstruction (e.g., nausea

with vomiting)

Penetration or perforation

(severe abdominal pain)

Cancer (e.g., weight loss,

anorexia)

Keep in mind, the risk of

cancer increases with age

Detect exposure:

ELISA serology

$15

(by clin. micro lab)

Office serum test $24

Detect active infection:

Stool antigen test $129

Urea breath test $479

(special preparation

required - see text)

TABLE 4

Preferred Treatment

Regimen for H. pylori

Induced PUD

Proton pump inhibitor

Clarithromycin

Either amoxicillin or

metronidazole

For examples of treatment

regimens and comparisons,

see Table 5.

UMHS Peptic Ulcer Guideline, May 2005

Table 5: Treatment of H. pylori Associated Peptic Ulcer Disease

Therapy

Approach

Eradication

Rate

Regimen

Duration

Cost b

10 days

14 days

$430-$480

Proton Pump Inhibitor Based Triple Therapy

Proton Pump Inhibitor bid c

Amoxicillin 1 gm bid ($1/day generic)

Clarithromycin 500 mg bid ($30/day brand)

80%-90%

10-14 days

Three compliance packaged as Prevpac (PPI = Lansoprazole)

80%-90%

14 days

80%-90%

10-14 days

Proton Pump Inhibitor bid

Clarithromycin 250mg bid ($15/day brand) or 500 mg bid ($30/day

brand). [If intolerant or allergic, substitute Amoxicillin 1 gm bid

[$1/day generic).]

Metronidazole 500 mg bid ($1/day generic)

$602-$672

$279

$280-$480

$392-$672

NIH "Conventional Triple Therapy"

Bismuth (Pepto-Bismol) 2 tablets daily ($1/day generic or brand)

Metronidazole 250 mg daily ($1/day generic)

Tetracycline 500 mg daily ($1/day). [If intolerant or allergic,

substitute Amoxicillin 1 gm bid ($1/day generic).]

d

e

Must add either H2 blocker bid or PPI daily

75%-85%

14 days

$56-$168

Conventional triple therapy package: Helidac ($14/day)

d

e

Must add either H2 blocker bid or PPI daily

75%-85%

14 days

$210-$322

a

b

Noncompliance increases with duration and with number of drugs employed.

Cost = Average wholesale price based -10% for brand products and Maximum Allowable Cost (MAC) + $3 for generics

on 30-day supply or less, Amerisource AWP 01/05 & Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan Mac List, 01/31/05.

c

PPIs for PPI triple therapy: Omeprazole 20 mg bid ($3/day generic; $8/day brand) or Lansoprazole 15 or 30 mg bid (both

$9/day brand).

d

H2 blockers with conventional triple therapy: Cimetidine 400 mg bid ($1/day generic; $3/day brand), Famotidine 20 mg

bid ($1/day generic; $4/day brand), Nizatidine 150 mg bid ($1/day generic; $6/day brand), or Ranitidine 150 mg bid

($1/day generic; $4/day brand)

e

PPIs with conventional triple therapy: Lansoprazole 15 or 30 mg daily ($9/day generic & brand) or Omeprazole 20 mg

daily ($3/day generic; $8/day brand)

chronic maintenance H2-blocker therapy for ulcer disease

may no longer require these medications given that the

likelihood of ulcer recurrence is nearly eliminated.

Clinical Problem (continued)

Need to implement antibiotic treatment of peptic ulcer

disease.

A federally-funded survey of over 1,000

gastroenterologists and primary care physicians revealed

considerable uncertainty regarding the under diagnosis and

treatment of HP infection in selected patient populations.

Claims data show a pattern of under treatment of patients

with PUD.

Rationale for Recommendations

Underlying epidemiology and general approach.

Individuals with symptoms of PUD may or may not have

ulcers. Randomized controlled trials treating H. pylori in

patients known to have PUD have demonstrated

significantly improved outcomes and reduced treatment

costs. However, 80% or more of patients with PUD-like

symptoms do not have ulcers. The clinical benefits of H.

Overuse of chronic anti-secretory medications.

Prospective studies reveal that non-NSAID induced PUD

can be effectively cured when HP infection is

successfully eradicated. Therefore, individuals receiving

3

UMHS Peptic Ulcer Guideline, May 2005

great majority of HP infected individuals never develop

PUD.

pylori diagnosis and treatment in symptomatic patients with

non-ulcer dyspepsia remain controversial -- several

controlled trials have produced inconsistent results. The

specific benefit of testing and treating H. pylori in a

population with PUD symptoms depends on the underlying

prevalence of ulcers and non-ulcer dyspepsia and HP

infection in the population.

Testing for H. pylori. Diagnostic endoscopy, the gold

standard for diagnosing active HP infection, is more costly

and invasive than the non-invasive tests. Non-invasive HP

testing is currently recommended for uncomplicated

dyspepsia patients and individuals with a history of PUD

(see Table 3).

Even with a low prevalence of ulcers in the population, the

benefits of testing and treating H. pylori in that subgroup

are very significant and the cost very low. The cost-benefit

is sufficient that H. pylori testing and treatment is

appropriate for all patients with suspected PUD, even

though the majority of patients will not benefit.

Two categories of tests. Two general categories of noninvasive HP tests are now available:

tests that identify active infection.

tests that detect antibodies (exposure)

This distinction is important because antibodies (i.e.

positive immune response) only indicate the presence of HP

at some time. Antibody tests do not differentiate between

previously eradicated HP and currently active HP.

Therefore, testing for active HP infection is more

appropriate in areas with low prevalence of active HP

infection. In these areas, serologic tests are more likely to

be positive due to previously eradicated infections,

resulting in unnecessary treatment of individuals who are

not actively infected.

Causes of PUD. The two major etiologic factors for PUD

are: (1) use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

(NSAIDs) or COX-2s (COX-2s provide only a small

reduction in GI complications compared to NSAIDs, and

only in the short term) and (2) HP infection. Patients

taking NSAIDs or COX-2s who experience symptoms of

an uncomplicated peptic ulcer should immediately stop

taking the NSAIDs or COX-2s and begin taking

antisecretory medication. If the NSAIDs are the cause of

the symptoms, the symptoms should resolve a few within

days, generally less than 14.

Compared to tests for active infection, tests for

antibodies are simpler to administer, provide a faster result,

and are less expensive. However, the probability that

positive antibody test reflects active infection will decrease

as the proportion of patients with previously eradicated HP

increases. Testing for active infection may be more cost

effective in populations likely to have had past HP

exposure, but not ongoing infection. Successfully treated

patients include both (1) patients given antibiotics

specifically for HP (2) patients with undiagnosed HP who

were given antibiotics for another infection and the

antibiotics also eradicated the HP, (3) spontaneous

eradication of HP infection. In the absence of rates for

population infection and eradication, the selection of the

type of non-invasive HP test to use for an individual patient

is a clinical judgment based on factors such as:

probability of a previously eradicated infection

probability of a current active infection

need to document active infection

need for rapid result

patient preferences

cost (both of test and possible unnecessary treatment)

Symptoms. Abdominal pain in patient with PUD is

classically described as gnawing or burning, non-radiating,

epigastric pain, which occurs 2-3 hours after meals (when

stomach is empty) or at night. The pain is relieved with

food or antacids (see Table 1). However, less than 50% of

patients with those symptoms are actually found to have

peptic ulcer disease. The most discriminating symptom of

pain awakening the patient from sleep between 12-3 a.m.

affects 2/3 of duodenal ulcer patients and 1/3 of gastric

ulcer patients. However, these same symptoms are also

seen in 1/3 of patients with non-ulcer dyspepsia.

Complicated ulcers. Patients with signs or symptoms of

bleeding, obstruction, penetration or perforation may

require specific endoscopic or surgical treatment. A

specific diagnosis should be made in these patients as

malignancy can present with these findings. Empiric

therapy should not be used in this setting.

Advanced Age. Peptic ulcer disease due to HP is unlikely

to have its initial presentation at age >50 years. Given the

increased risk of malignancy in this patient group early

referral is recommended.

Tests for active HP. Tests for active HP include fecal

HP antigen testing and urea breath testing.

H. pylori. With the exception of patients with gastrinoma

and those taking NSAIDs, most duodenal ulcer patients and

in at least two-thirds of patients with gastric ulcers are

infected with HP. In western countries, HP infects about

20% of persons below the age of 40 years and about 50%

of persons above the age of 60 years. The incidence of HP

infection in developing countries is much higher, and by

adulthood most people are infected. Thus, it is essential to

inquire whether an individual spent time in an endemic area

for HP. While HP infection is usually found with PUD, the

The stool antigen test has been reported to have a

sensitivity and specificity of more than 90% in untreated

patients with suspected HP infection. The test requires

collection of a stool sample the size of an acorn by either

the clinician or the patient. This test must be performed in

a laboratory by trained personnel. (An office based stool

test may be available in the near future.)

For the urea breath test, the patient drinks an oral

preparation containing 13C or 14C-labeled urea. This test

4

UMHS Peptic Ulcer Guideline, May 2005

has a sensitivity and specificity of more than 90% for active

infection.

However, this test requires more patient

preparation and is more expensive. A number of drugs can

adversely affect the accuracy of urea breath tests. Prior to

urea breath testing, antibiotics and bismuth should be

withheld for at least 4 weeks, proton pump inhibitors

should be withheld for at least 7 days, and patients should

fast for at least 6 hours.

Continued anti-secretory therapy post-antibiotic

therapy. Antibiotic therapy alone cures ulcer disease.

Anitsecretory therapy beyond 2 weeks after eradication

should not be required, and if symptoms persist, referral is

appropriate.

Controversial Issues Involving H. pylori Treatment

Antibody testing. Serologic testing for HP is an

alternative cost-effective method for diagnosis of HP

infection in untreated patients. HP serologic tests detect

antibodies to HP with a sensitivity and specificity of

approximately 90%. In populations with low disease

prevalence, the positive predictive value of the test falls

dramatically, leading to unnecessary treatment. Since the

incidence of PUD does not increase with age, a positive

serology in older persons is less likely to predict the

presence of active PUD. If a symptomatic patient has

negative serology in the absence of NSAIDs use, the

diagnosis of PUD is very unlikely.

Dyspepsia. Whether HP causes dyspeptic symptoms in the

absence of ulcer disease is controversial. The weight of the

evidence suggests the incidence of HP in patients with

dyspepsia is no higher than properly matched control

populations. Eradication of HP did not reliably control

symptoms in most patients with non-ulcer dyspepsia

patients enrolled in randomized studies, and control of

symptoms was at rates similar to standard care.

Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD). There is no

clinical evidence suggesting a relationship between HP and

GERD.

Patients with classic symptoms of reflux

(heartburn, acid regurgitation) should not be tested for HP

infection and are not considered in this guideline.

Office based serologic tests are less accurate than

laboratory based ELISA tests. Office based serologic tests

have the advantage of providing a result within a half hour.

Testing to document HP eradication.

It remains

controversial whether individuals who are asymptomatic

after therapy should undergo a confirmatory test to

establish cure. Since treatment is not effective is some

cases (> 20%), individuals at high risk for HP-associated

complications (e.g., prior bleeding ulcer) should undergo

confirmatory testing with either the stool antigen or urea

breath test to confirm HP cure [C*] . (Serology has no role

in confirmatory testing.)

Serology tests should be used only for initial diagnosis

of HP since antibody levels often remain elevated after HP

is eliminated. Serology tests should not be used after a

patient has been treated for HP to confirm cure.

Treatment of HP. The choice of therapy should consider

effectiveness, cost of various regimens vs. side effects.

Table 5 presents examples of alternative regimens. PPIs

have in-vitro activity against HP.

A PPI plus

clarithromycin plus either amoxicillin or metronidazole

have demonstrated impressive eradication rates when used

for 10-14 days. Amoxicillin is preferred for patients who

have been treated with metronidazole previously.

Metronidazole is preferred for patients allergic to penicillin.

Many patients have persistent symptoms after documented

HP cure. If a patient has recurrent symptoms after a course

of HP eradication therapy, consultation for further

diagnostic evaluation is warranted [D*] .

Cancer prevention. Epidemiologic evidence suggests that

infection with HP is associated with a greater than twofold increased risk of developing gastric cancer. However

due the uncertainty regarding the benefit of HP eradication

on reducing cancer risk, wide-spread screening for HP in

asymptomatic individuals cannot be recommended at this

time. For persons at high risk for gastric cancer (e.g., first

degree relatives) screening can be considered on a case by

case basis.

Conventional Triple Therapy for H. pylori (HP) for

two weeks is the best studied, highly effective anti-HP

therapy (> 85% eradication). The duration and multidrug

nature of this regimen have been associated with decreased

compliance leading to potential failure to eradicate. .

Not recommended is a dual therapy of single PPI and a

single antibiotic. Despite initial encouraging results from

Germany, the U.S. experience has been disappointing.

Eradication rates with a PPI and amoxicillin in the U.S.

have been less than 50%.

Information the Patient Needs to Know

Evaluation of the patient post-antibiotic therapy.

Resolution of ulcer symptoms is rapid, typically within 7

days. The persistence (or redevelopment) of symptoms

after 14 days of antibiotic and anti-secretory drug therapy

suggests failure of ulcer healing or an alternative diagnosis

such as cancer. Referral to the specialist for further

evaluation is recommended over continued antisecretory

drug use.

Cause. Ulcers are frequently associated with a type of

bacteria and antibiotic treatment is necessary.

Complete antibiotic treatment. It is important to finish

the entire course of the antibiotic treatment even if you

are feeling better.

UMHS Peptic Ulcer Guideline, May 2005

Alarm symptoms. Symptoms which require early

follow up include blood in stools or black tarry stools,

vomiting, severe abdominal pain.

Team Member

Relationship

Company

A. Mark Fendrick, MD Speakers bureau Astra Zeneca, Tap

Next option. If symptoms persist after HP eradication

therapy you may need to undergo an endoscopy to get a

better understanding of what is causing your symptoms.

Consultant

Randall Forsch, MD

Van Harrison, PhD

James Scheiman, MD

Strategy for Literature Search

(None)

(None)

Grant/research

support

Astra Zeneca,

Tap, Meridian

Diagnostics

AstraZeneca,

Pfizer, Merck

The literature search began with results of literature

searches performed for the period 1986 through Sep. 1998

for earlier versions of this guideline. The literature search

for this update was conducted prospectively using the

major keywords of: peptic ulcer and H. pylori, dyspepsia

& H. pylori, guidelines, controlled trials, adults, published

from July 1998 through July 2004 on Medline. Terms used

for specific treatment topic searches within the major key

words included: history, serologic testing, endoscopy,

other references to diagnosis, antibiotics, antisecretory

drugs, other references to treatment, and other references

not included in the previous specific topics. The search was

conducted in components each keyed to a specific causal

link in a formal problem structure (available upon request).

The search was supplemented with very recent clinical

trials known to expert members of the panel. Negative

trials were specifically sought. The search was a single

cycle. Conclusions were based on prospective randomized

clinical trials if available, to the exclusion of other data; if

RCTs were not available, observational studies were

admitted to consideration. If no such data were available

for a given link in the problem formulation, expert opinion

was used to estimate effect size.

In addition to current team members on the front page, the

following individuals are acknowledged for thier

contributions to the 1999 version of this guideline: Ray

Rion, MD, Family Medicine; Connie Standiford, MD,

General Internal Medicine.

Related National Guidelines

Annotated References

The UMHS Clinical Guideline on PUD is consistent with

the American Gastroenterological Association Medical

Position Statement on Evaluation of Dyspepsia (1998).

(See annotated references below.)

American Gastroenterological Association Clinical Practice

and Practice Economics Committee.

AGA Medical

Position

Statement:

Evaluation

of

Dyspepsia.

Gastroenterology, 1998; 114: 579-581.

Consultant

AstraZeneca,

Merck,

Nitromed,

McNeil,

Novartis, TAP,

Pfizer, Pozen,

The GI Company

Speakers bureau

AstraZeneca,

TAP, Wyeth,

Boheringer

Ingelheim

Acknowledgments

A summary of recommendations concerning the

optimal management of patients presenting with

dyspepsia. A 14 page technical review and literature

summary follows the position statement.

Disclosures

The University of Michigan Health System endorses the

Guidelines of the Association of American Medical

Colleges and the Standards of the Accreditation Council for

Continuing Medical Education that the individuals who

present educational activities disclose significant

relationships with commercial companies whose products

or services are discussed. Disclosure of a relationship is

not intended to suggest bias in the information presented,

but is made to provide readers with information that might

be of potential importance to their evaluation of the

information.

Chey WD, Fendrick AM. Non-invasive H. pylori testing

for the "test and treat" strategy: a decision analysis to

assess the impact of past infection on test choice. Archives

of Internal Medicine, 2001; 161: 2129-32.

Analysis demonstrating the advantages of active HP

testing over HP serology in terms of reducing

inappropriate antibiotic treatment in populations with

low rates of active HP infection.

Fendrick AM, Chernew ME, Hirth RA, Bloom BS.

Alternative management strategies for patients with

suspected peptic ulcer disease. Ann Int Med 1995;

123:260-8.

6

UMHS Peptic Ulcer Guideline, May 2005

An economic analysis that supports the role for initial

noninvasive diagnosis and treatment of HP in patients

with suspected ulcer disease.

Ladabaum U, Chey WD, Scheiman JM, Fendrick AM.

Reappraisal of non-invasive management strategies for

uninvestigated dyspepsia: a cost-minimization analysis.

AlimentPharmacol Ther, 2002; 16: 1491-1501.

Decision analysis identifying HP prevalence and

likelihood of peptic ulcer disease as determinants for

initial noninvasive management.

McColl KE, Murray LS, Gillen D, Walker A, Wirz A.

Fletcher J, Mowat C, Henry E, Kelman A, Dickson A.

Randomized trial of endoscapy with testing for

Helicobacter pylori compared with non-invasive H pylori

testing alone in the management of dyspepsia. BBMG,

2002; 324(7344): 999-1002.

An example of trials demonstrating non-invasive

testing for H pylori is as effective and safe as

endoscopy and less uncomfortable and distressing for

the patient.

Peterson WL, Fendrick AM, Cave Dr, et al. Helicobacter

pylori-related disease: guidelines for testing and treatment.

Archives of Internal Medicine, 2000; 10(9): 1285-91.

A consensus document for H pylori diagnosis and

treatment.

Sonnenberg A, Schwartz JS, Cutler AF, Vakil N, Bloom

BS. Cost savings in duodenal ulcer therapy through

Helicobacter

pylori

eradication

compared

with

conventional therapies: results of a randomized, doubleblind, multi-center trial. Gastrointestinal Utilization Trial

Study Group.

Archives of Internal Medicine 1998;

158:852-860

This large study demonstrates the effect and cost

savings of initial serology based treatment of HP in

patients with documented peptic ulcer disease.

UMHS Peptic Ulcer Guideline, May 2005

You might also like

- Dak Enak PerutDocument25 pagesDak Enak PerutIbnu SinaNo ratings yet

- Dak Enak PerutDocument25 pagesDak Enak PerutIbnu SinaNo ratings yet

- Dak Enak PerutDocument25 pagesDak Enak PerutIbnu SinaNo ratings yet

- Dak Enak PerutDocument25 pagesDak Enak PerutIbnu SinaNo ratings yet

- Dak Enak PerutDocument25 pagesDak Enak PerutIbnu SinaNo ratings yet

- Dyspepsia: Treatment Post DiagnosisDocument25 pagesDyspepsia: Treatment Post DiagnosisIbnu SinaNo ratings yet

- Dak Enak PerutDocument25 pagesDak Enak PerutIbnu SinaNo ratings yet

- Dak Enak PerutDocument25 pagesDak Enak PerutIbnu SinaNo ratings yet

- Gastritis Treatment and H Pylori GuidelinesDocument25 pagesGastritis Treatment and H Pylori GuidelinesIbnu SinaNo ratings yet

- H. Pylori Treatment GuidelinesDocument25 pagesH. Pylori Treatment GuidelinesIbnu SinaNo ratings yet

- Dak Enak PerutDocument25 pagesDak Enak PerutIbnu SinaNo ratings yet

- Dak Enak PerutDocument25 pagesDak Enak PerutIbnu SinaNo ratings yet

- Dak Enak PerutDocument25 pagesDak Enak PerutIbnu SinaNo ratings yet

- Dak Enak PerutDocument25 pagesDak Enak PerutIbnu SinaNo ratings yet

- Treatment H PyloriDocument8 pagesTreatment H PyloriSeanglaw SituNo ratings yet

- Acute Diarrheal Infections in AdultsDocument21 pagesAcute Diarrheal Infections in AdultsNitiwut MeenunNo ratings yet

- Maastricht IvDocument20 pagesMaastricht IvFlorina MarianaNo ratings yet

- Peptic Ulcer Case Study 1Document9 pagesPeptic Ulcer Case Study 1Alejandro Daniel Landa MoralesNo ratings yet

- Approach To Uninvestigated DyspepsiaDocument18 pagesApproach To Uninvestigated DyspepsiaAshish SatyalNo ratings yet

- Helicobacter Pylori - The Latest in Diagnosis and TreatmentDocument5 pagesHelicobacter Pylori - The Latest in Diagnosis and TreatmentekramsNo ratings yet

- ACG and CAG Clinical Guideline: Management of DyspepsiaDocument26 pagesACG and CAG Clinical Guideline: Management of Dyspepsiajenny puentesNo ratings yet

- Dyspepsia Management Guidelines For The MillenniumDocument7 pagesDyspepsia Management Guidelines For The MillenniumAlia ZuhriNo ratings yet

- GeRD 2008Document6 pagesGeRD 2008lexyuNo ratings yet

- Algoritma GerdDocument14 pagesAlgoritma GerdRivaldi ArdiansyahNo ratings yet

- CCO HCV Frontline 2013 DownloadableDocument46 pagesCCO HCV Frontline 2013 DownloadableKaram Ali ShahNo ratings yet

- Nutrition Journal: Nutrition Support in Cancer Patients: A Brief Review and Suggestion For Standard Indications CriteriaDocument5 pagesNutrition Journal: Nutrition Support in Cancer Patients: A Brief Review and Suggestion For Standard Indications CriteriaSunardiasihNo ratings yet

- Update On The Evaluation and Management of Functional DyspepsiaDocument7 pagesUpdate On The Evaluation and Management of Functional DyspepsiaDenuna EnjanaNo ratings yet

- Boghossian Et Al-2017-Cochrane Database of Systematic ReviewsDocument4 pagesBoghossian Et Al-2017-Cochrane Database of Systematic ReviewsrisdalNo ratings yet

- HP Toronto Consensus 2016 PDFDocument33 pagesHP Toronto Consensus 2016 PDFhoangducnamNo ratings yet

- Helicobacter PyloriDocument8 pagesHelicobacter PyloriQuỳnh ThưNo ratings yet

- 8 Nausea and Vomiting, Diarrhea, Constipation (Pedrosa)Document27 pages8 Nausea and Vomiting, Diarrhea, Constipation (Pedrosa)JEHAN HADJIUSMANNo ratings yet

- Effect of Intensive Health Education On Adherence To Treatment in Sputum Positive Pulmonary Tuberculosis PatientsDocument6 pagesEffect of Intensive Health Education On Adherence To Treatment in Sputum Positive Pulmonary Tuberculosis PatientspocutindahNo ratings yet

- Final Ugib Sec To BpudDocument17 pagesFinal Ugib Sec To BpudBaby Kate BONGCARASNo ratings yet

- Treating Peptic Ulcer Disease and H. pylori InfectionDocument3 pagesTreating Peptic Ulcer Disease and H. pylori InfectionYosep BeNo ratings yet

- Manage IBD with Biomarkers, Drug MonitoringDocument13 pagesManage IBD with Biomarkers, Drug MonitoringShafa ShaviraNo ratings yet

- Chiba Proposal Rough DraftDocument13 pagesChiba Proposal Rough Draftapi-285852246No ratings yet

- Cmmi2021 2135924Document7 pagesCmmi2021 2135924ken3365448No ratings yet

- Helicobacter Pylori: Eradication - An Update On The Latest TherapiesDocument5 pagesHelicobacter Pylori: Eradication - An Update On The Latest TherapiesBaim FarmaNo ratings yet

- DyspepsiaDocument26 pagesDyspepsiaYaasin R NNo ratings yet

- Review Article On Safety and Efficacy of Sequential Versus Triple Therapies For Treating H. Pylori InfectionDocument7 pagesReview Article On Safety and Efficacy of Sequential Versus Triple Therapies For Treating H. Pylori InfectionIjsrmt digital libraryNo ratings yet

- Current Diagnosis and Management of Suspected Reflux Symptoms Refractory to PPI TherapyDocument9 pagesCurrent Diagnosis and Management of Suspected Reflux Symptoms Refractory to PPI TherapyMuhammad Wim AdhitamaNo ratings yet

- Riris Sutrisno (G 501 11 038) - TherapyDocument8 pagesRiris Sutrisno (G 501 11 038) - TherapyRiris SutrisnoNo ratings yet

- Ppi + IbdDocument26 pagesPpi + IbdKevin OwenNo ratings yet

- Walsh 2016Document8 pagesWalsh 2016Ambulatório Dieta Cetogênica HUBNo ratings yet

- Fast Hug FaithDocument4 pagesFast Hug FaithHenrique Yuji Watanabe SilvaNo ratings yet

- Indications, Contraindications and Monitoring of Enteral NutritionDocument13 pagesIndications, Contraindications and Monitoring of Enteral Nutritionbocah_britpopNo ratings yet

- 10.1016@j.giec.2019.12.005Document13 pages10.1016@j.giec.2019.12.005teranrobleswaltergabrielNo ratings yet

- CPG Ulcer enDocument24 pagesCPG Ulcer enAlina BotnarencoNo ratings yet

- Camille Ri 2012Document20 pagesCamille Ri 2012Jose Lopez FuentesNo ratings yet

- Complications of Proton Pump Inhibitor Therapy 2017Document14 pagesComplications of Proton Pump Inhibitor Therapy 2017Ingrid Miroslava Reyes DiazNo ratings yet

- American College of Gastroenterology Guideline On The Management of Helicobacter Pylori InfectionDocument18 pagesAmerican College of Gastroenterology Guideline On The Management of Helicobacter Pylori InfectionShinichi Ferry RoferdiNo ratings yet

- ACG Guideline GERD March 2013Document21 pagesACG Guideline GERD March 2013Arri KurniawanNo ratings yet

- Top Trials in Gastroenterology & HepatologyFrom EverandTop Trials in Gastroenterology & HepatologyRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (7)

- A Review of The Diagnosis and Management of Reflux DiseaseDocument1 pageA Review of The Diagnosis and Management of Reflux DiseaseScutelnicLiliaNo ratings yet

- Algoritma GerdDocument14 pagesAlgoritma GerdBintang AnjaniNo ratings yet

- Critical Appraisal KADocument36 pagesCritical Appraisal KAKentVilandkaNo ratings yet

- Dyspepsia Hypertension 1Document32 pagesDyspepsia Hypertension 1Jeno Luis AcubNo ratings yet

- Association of Symptoms With Eating Habits and Food Preferences in Chronic Gastritis Patients A CrossSectional StudyDocument11 pagesAssociation of Symptoms With Eating Habits and Food Preferences in Chronic Gastritis Patients A CrossSectional StudyDayanne WesllaNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S001650850862925X MainDocument2 pages1 s2.0 S001650850862925X MainMirza RisqaNo ratings yet

- Publikasj JurnalDocument6 pagesPublikasj JurnalFebrian StoreNo ratings yet

- Survanta PiDocument11 pagesSurvanta PisyafiraNo ratings yet

- JNC 8 Guideline Algorithm for Treating HypertensionDocument2 pagesJNC 8 Guideline Algorithm for Treating HypertensionTaradifaNurInsi0% (1)

- Beractant for treatment of respiratory distress syndrome in premature infantsDocument2 pagesBeractant for treatment of respiratory distress syndrome in premature infantssyafiraNo ratings yet

- Ulcer BleedingDocument16 pagesUlcer Bleedingseb2008No ratings yet

- Milliequivalents, Millimoles, and Milliosmoles ExplainedDocument17 pagesMilliequivalents, Millimoles, and Milliosmoles ExplainedMuhammad SafdarNo ratings yet

- Hospital Pharmacy Management & Organization PDFDocument17 pagesHospital Pharmacy Management & Organization PDFmajdNo ratings yet

- Xanthoma in A Child As The First Presentation of Type One Diabetes Mellitus 2161 0665.1000226Document2 pagesXanthoma in A Child As The First Presentation of Type One Diabetes Mellitus 2161 0665.1000226syafiraNo ratings yet

- Menghitung Makrofag Dari BCGDocument14 pagesMenghitung Makrofag Dari BCGsyafiraNo ratings yet

- Antiinflamasi Daun DewaDocument6 pagesAntiinflamasi Daun DewasyafiraNo ratings yet

- Biocidin Usage ChartDocument2 pagesBiocidin Usage Chartdarshansinghxp78% (9)

- Pharmaceutical Sciences I: Dosage Form DesignDocument46 pagesPharmaceutical Sciences I: Dosage Form DesignKiEl GlorkNo ratings yet

- Revco BrochureDocument24 pagesRevco BrochuremarcosfactoryNo ratings yet

- Ystral Mixing Tech. CataloueDocument11 pagesYstral Mixing Tech. Catalouemmk111No ratings yet

- A Kiss Before DyingDocument6 pagesA Kiss Before Dyingerik perete pinedaNo ratings yet

- Electronic Submission Article 572 Data Questions Answers - enDocument75 pagesElectronic Submission Article 572 Data Questions Answers - enHarrisonNo ratings yet

- Analisis Simetikon PDFDocument9 pagesAnalisis Simetikon PDFArini Musfiroh50% (2)

- India's Pharmaceutical SWOT Analysis and Strategic OptionsDocument10 pagesIndia's Pharmaceutical SWOT Analysis and Strategic OptionsJaimin PatelNo ratings yet

- Sales s2 2023 Uc BatamDocument12 pagesSales s2 2023 Uc BatamHerry PoernomoNo ratings yet

- A Review - Dosing Issues When Using Minocin/Minocycline To Treat SarcoidosisDocument3 pagesA Review - Dosing Issues When Using Minocin/Minocycline To Treat SarcoidosisIonpropulsionNo ratings yet

- Local Anesthesia For ChildrenDocument107 pagesLocal Anesthesia For Childrenmarinacretu1No ratings yet

- Drugs Acting On GitDocument70 pagesDrugs Acting On GitUkash sukarmanNo ratings yet

- tmp4DA0 TMPDocument9 pagestmp4DA0 TMPFrontiersNo ratings yet

- Raynaud Syndrome Brochure-1 1Document2 pagesRaynaud Syndrome Brochure-1 1api-340995574No ratings yet

- Drugs of Abuse PDFDocument321 pagesDrugs of Abuse PDFAnonymous Gb9EyW100% (1)

- National Essential Drug List (Malaysia) PDFDocument11 pagesNational Essential Drug List (Malaysia) PDFKah Jun100% (1)

- 196-Article Text-270-1-10-20180208Document12 pages196-Article Text-270-1-10-20180208AdelineNo ratings yet

- Prescription Regulation TableDocument2 pagesPrescription Regulation TableKiranNo ratings yet

- Dietalinea - Book 2018 PDFDocument41 pagesDietalinea - Book 2018 PDFGabriela MillaNo ratings yet

- Alcohol Health and Medical Issues Today PDFDocument264 pagesAlcohol Health and Medical Issues Today PDFBranko PjevićNo ratings yet

- Cosmetic ManufacturersDocument50 pagesCosmetic Manufacturersyudhvir_msc75% (4)

- Quality Management Systems GuideDocument23 pagesQuality Management Systems GuideShivam Dave100% (1)

- Ertapenem Nursing ResponsibilitiesDocument3 pagesErtapenem Nursing ResponsibilitiesBea Dela CenaNo ratings yet

- Bobath ArticleDocument8 pagesBobath ArticleChristopher Chew Dian MingNo ratings yet

- Pharam GuideDocument4,386 pagesPharam Guideابُوالبَتُول ڈاکٹر صفدر علی قادری رضوی100% (1)

- Cell Bio1Document7 pagesCell Bio1AnyaNo ratings yet

- Verapamil OdtDocument62 pagesVerapamil OdtKumar GalipellyNo ratings yet

- Omar Changed Stand, Took Escape Route: Geelani: CM'S Position Reduced To A Mockery: PDPDocument8 pagesOmar Changed Stand, Took Escape Route: Geelani: CM'S Position Reduced To A Mockery: PDPthestudentageNo ratings yet

- Tablet Disintegration Test and Basket Rack AssemblyDocument2 pagesTablet Disintegration Test and Basket Rack AssemblyPhoenix100% (1)

- 1852 Xefo 1329745487 PDFDocument2 pages1852 Xefo 1329745487 PDFAlfyGototronNo ratings yet