Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Article 16

Uploaded by

avinashOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Article 16

Uploaded by

avinashCopyright:

Available Formats

Article 16

Article 16

Submitted To:

Submitted By:

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

I owe a great many thanks to a great many people who helped and supported me during the

writing of this project.

Article 16

My deepest thanks to my Constitutional Law Lecturer, for guiding me and correcting various

documents of mine with attention and care. He has taken pain to go through the project and

make necessary corrections as and when needed.

I would also thank my Institution and my faculty members without whom this project would

have been a distant reality. I also extend my heartfelt thanks to my family and well-wishers.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION....................................................................................................... 3

Article 16 vs. Article 15................................................................................................ 4

Equality of Opportunity- State may lay down Qualifications or Conditions [Article 16(1)]..............5

Members of Separate and Independent Classes of Service...................................................5

Educational Qualifications as Basis of Classification.........................................................6

Article 16

Matters Relating to Employment or Appointment.............................................................6

Cut-off Date for Eligibility......................................................................................... 6

Equality of Opportunity- Process of Selection..................................................................7

Written Test vis-a-vis Viva Voice Test............................................................................7

Annual Confidential ReportCommunication of Entries....................................................7

Filling up Posts Over and Above Those Advertised...........................................................7

Regularisation of Ad Hoc Employees............................................................................ 8

No Discrimination on the Ground of Religion, Race, Etc. [(Article 16(2)]..................................8

Requirement as to Residence in a State [Article 16(3)]..........................................................9

Reservation of Posts for Backward Classes [Article 16(4)].....................................................9

Article 16(4) is not an Exception to Article 16(1)............................................................10

Scope of Article 16(4)............................................................................................. 10

Justice Ram Nandan Committee-Creamy Layer...........................................................13

Reservation in Super-Specialities...............................................................................13

Backward Classes U/A 16(4)..................................................................................... 13

Article 16(4) & Article 335....................................................................................... 16

Article 16(4) of the Indian Constitution and the Hohfeldian concept of Rights:.......................17

Reservation in PromotionSeventy-seventh Amendment, 1995

[Article 16(4A)]............20

Exclusion of 50% Ceiling w.r.t. Carry Forward Reserved Vacancies [Article 16(4B)]...............20

Reservation in Promotion: Catch-up Rule Negated- 85th Amendment, 2001..........................20

Principles of Reservation do not apply to Isolated Post.....................................................21

Offices under a Religious or Denominational Institution [Article 16(5)]...................................21

Equal Pay for Equal Work........................................................................................... 22

ARTICLE 16 AS A BUNDLE OF CONTRADICTIONS.....................................................23

AN EPILOGUE........................................................................................................ 24

BIBIOGRAPHY....................................................................................................... 25

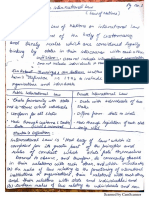

INTRODUCTION

Part III of the Constitution of India, titled as Fundamental Rights (Articles 12 to 36),

secures to the people of India, certain basic, natural and inalienable rights. The inclusion of a

chapter on Fundamental Rights, in the Constitution, is in accord with the trend of modern

democratic thought. These rights are basic to a democratic polity. The guarantee of certain

basic human rights is an indispensable requirement of a free society.

Article 16

RIGHT TO EQUALITY (Articles 14 to 18)

The first Fundamental Right secured to the people of India is the Right to Equality. It has

the following provisions:

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

Equality before Law or Equal Protection of Laws (Article 14)

Prohibition of Discrimination Against Citizens (Article 15)

Equality of Opportunity in Public Employment (Article 16)

Abolition of Untouchability (Article 17)

Abolition of Titles (Article 18)

EQUALITY OF OPPORTUNITY IN MATTERS OF PUBLIC

EMPLOYMENT

(Article 16)

Another particular application of the general principal of equality or protection clause

enshrined in Article 14 is contained in Article 16.

Clause (1) of Article 16 guarantees to all citizens, equality of opportunity, matters relating to

employment or appointment to any office under the State. (2) further strengthens the

guarantee contained in Clause (1) by declaring that No citizen shall, on grounds only of

religion, race, caste, sex, descent, place of birth, residence or any of them, be ineligible for, or

discriminated against in respect of, any employment or office under the State. Clauses (3),

(4) and (5) of Article 16 contain exceptions to the rule of equality opportunity, embodied in

Clauses (1) and (2).

Article 16 vs. Article 15

Article 16 is applicable only in case of employment or appointment to an official under the

State.

Article 16 is similar to Article 15 in one respect, i.e., both these provisions prohibit

discrimination against citizens on specified grounds. However, Article is wider in operation

than Article 16.

While, Article 16 prohibits discrimination only in respect to one particular matter, i.e.,

relating to employment or appointment to posts under the State, Article 15 lays down a

general rule and prohibits discrimination in respect to all or any matters.

In respect, Article 16 is wider than Article 15, i.e., the grounds on the basis which

discrimination is prohibited. While, Article 15 prohibits discrimination on any of the five

grounds, i.e., religion, race, caste, sex or place birth, Article 16 contains seven prohibited

grounds, i.e., religion, race, caste, descent, place of birth or residence. Article 15 does not

contain descent residence as the prohibited grounds of discrimination. However, both

Articles can be invoked by citizens only.

Article 16

Equality of Opportunity- State may lay down Qualifications or

Conditions[Article 16(1)]

Article 16 does not prevent the State from prescribing the requisite qualifications and the

selection procedure for recruitment or appointment. It is further open to the appointing

authority to lay down such pre-requisite conditions of appointment as would be conducive to

the maintenance of proper discipline amongst government servants. The qualifications

prescribed may, therefore, besides mental excellence, include physical fitness, sense of

discipline, moral integrity, and loyalty to the State.

However, the qualifications or the selective test must not be arbitrary. These be based on

reasonable ground and must have nexus with the efficient performance of the duties and

obligations of the particular office or post. Also, the qualifications cannot be altered and

applied with retrospective effect. In Pandurangarao v. Andhra Pradesh Public Service

Commission, the rule relating to qualifications for the appointment to the posts of District

Munsiffs, by direct recruitment prescribed that the applicant must have been practising as an

Advocate in the High Court and he must have been actually practisingin the Courts of Civil

or Criminal jurisdiction in India for a period less than three years. The High Court in this

context meant Andhra Pradesh High Court. The object was that the persons to be appointed to

the posts of District Munsiffs must be having knowledge of local laws as well as knowledge

of the regional language and adequate experience at the bar. The application of the petitioner,

qualified in all other respects except that he was not at that time, practicing as an Advocate in

the Andhra High Court but in Mysore High Court, was rejected.

The Supreme Court held that the Rule which requires that only a lawyer practicing in the

Andhra Pradesh High Court, had introduced a classification between one class of Advocates

and the rest and the said classification was irrational inasmuch as there was no nexus between

the basis of the said classification and the object intended to be achieved by the relevant Rule,

i.e., knowledge of local laws as well as regional language and adequate experience at the

bar. The Rule was struck down as unconstitutional and ultra vires.

Members of Separate and Independent Classes of Service

There can be no rule of equality between members of separate and independent classes of

services.

In All India Station Masters Association. v. General Manager, Central Railway, a Rule

which provided for the promotion of Guards to the posts of Station Masters while ignoring

the Road-Side Station Masters, was held to be valid, since, the Guards and Roadside Station

Masters were recruited separately and trained separately and had separate avenues of

promotions. They, thus. formed two distinct and separate classes and for that reason there was

no scope for predicating equality or inequality of opportunity in the matters of promotion.

Article 16

Educational Qualifications as Basis of Classification

Educational qualifications can justifiably be made a basis of classification for purposes of

promotion to higher post.

In State of J, & K. v. T.N Khosa, the Supreme Court upheld the Jammu & Kashmir

Engineering (Gazetted Service) Recruitment Rules, 1970, whereunder only graduate

Assistant Engineers were eligible for promotion to the post of Assistant Executive Engineers.

Minimum qualifications fixed for a post are relevant not only for direct recruitment but also

for promotion and absorption. In Madhya Pradesh Electricity Board v. S.S. Modh, the

respondent.who was working as Sub-Overseer in the Chambal Hydel Scheme, Gandhisagar,

was refused absorption as Assistant Engineer under the Board on the merger of Hydel

Scheme with the Board, since he did not possess the minimum educational qualifications,

required for being appointed as Assistant Engineer under the Board, though his colleagues

possessing the qualifications were so absorbed. The Supreme Court held the action of the

Board as not violative of Article 16(1).

Matters Relating to Employment or Appointment

The words matters relating to employment or appointment explain that Article 16(1) is not

restricted to the initial matters, but applies to matters both prior and subsequent to the

employment, which are incidental to the employment and form part of the terms and

conditions of employment. Article 16(1), therefore, would have application in the matters

relating to initial appointments, subsequent promotions, termination of service, abolition of

posts, salary, periodical increments, grant of additional increment, fixation of seniority,

leave, gratuity, pension, age of superannuation, compulsory retirement, etc. The expression

appointment is said to take in, direct recruitment, promotion or transfer. The principle of

equal pay for equal work has also been interpreted to be the constitutional goal of Article

16(1).

Cut-off Date for Eligibility

It is well settled, supported by several decisions of the Apex Court that the cut-off date by

reference to which the eligibility requirement must be satisfied by the candidate seeking a

public employment is:

(i)

the date appointed by the relevant service rules;

(ii)

if there be no cut-off date appointed by the rules, than such date as may be appointed

for the purpose, in the advertisement calling for applications; that

(iii)

If there be no such date appointed then the eligibility criteria shall be applied, by

reference to the last date appointed, by which the applications have to be received by

the competent authority.

Article 16

Equality of Opportunity- Process of Selection

Recruitment to public services should be held strictly in accordance with the terms of

advertisement and the recruitment rules. Deviation from the rules allows entry to ineligible

persons and deprives many others who could have competed for the post. It is ruled that

public contracts are not largesse.

As regards the process of selection the Apex Court in Lila Dhar v. State of Rajasthan,

pointed out that the object of any process of selection for entry into public service was to

secure the best and the most suitable person for the job, avoiding patronage and favouritism.

Written Test vis-a-vis Viva Voice Test

Holding that it was not for the Court to lay down whether interview test should be held at all

or how many marks should be allowed for interview test, the Court in Lila Dhar v. State of

Rajasthan, said that the marks must be minimal so as to avoid charges of arbitrariness,

though not necessarily always. The Court opined that rigid rules could not be laid down in

these matters and that the matter might more appropriately be left to the wisdom of the

experts.

As regards the allocation of marks for viva voce vis-o-vis the marks for written examination,

it has been held that there cannot be any hard and fast rule of universal application. It would

depend upon the post and nature of duties to be performed.

Annual Confidential ReportCommunication of Entries

In Dev Dutt v. Union of 1ndia, the Apex Court, holding that fairness and transparency in

public administration enquired that all entries whether, poor, fair, average, good or very good,

in the ACR, must be communicated, ruled that non-communication of even a single entry

which might have the effect of destroying the career of an officer, would be arbitrary and as

such violative of Article 16 read with Article 14.

Filling up Posts Over and Above Those Advertised

The practice of selecting and preparing large list as compared to vacancy position by the

Service Selection Board has been deprecated by the Supreme Court in various decisions.

Selection of more candidates than mentioned in the requisition has been held without

jurisdiction.

It has held that appointment on additional posts would deprive candidates who were not

eligible for appointment to the posts on the last date for submission of application, of the

opportunity of being considered for appointment, on the additional posts.

The Supreme Court, in Madan Lal v. State of J. & K., held that since the requisition in the

present case was to fill only 22 posts, and the Commission had selected 20 candidates, the

appointments to be effected out of the said test would be on 11 posts and not beyond 11 posts.

However, mere calling more number of candidates for interview than prescribed under the

rules does not vitiate the selection.

Article 16

Further that the Government is under no obligation to fill up all the posts for which

requisition and advertisement are given.

Regularisation of Ad Hoc Employees

The Supreme Court has deprecated the regularisation and absorption of persons working as

part-time employees or on ad hoc basis, as it had become a common method of allowing back

door entries.

In State of U.P v. Ram Adhar, the Apex Court ruled that a temporary employee had no right

to the post. There was no principle of law, the Supreme Court in State Of Karnataka v.

Umadevi said, that a person appointed in a temporary capacity had a right to continue till

regular selection. Long continuance of such employees on irregular basis, would not entitle

them, to claim equality with regularly recruited employees.

No Discrimination on the Ground of Religion, Race, Etc. [(Article 16(2)]

Clause (2) of Article 16 declares No citizen shall, on grounds only of religion, race, caste,

sex, descent, place of birth, residence or any of them, be ineligible for, or discriminated

against in respect of, any employment or office under the State.

The expression discriminated against the word only in Article 16(2) bear the same

meanings as in Article 15. Therefore, if the differentiation and bias are based on any of the

grounds mentioned in Article 16(2), the impugned law or State action becomes ipso facto

repugnant to the Constitution.

In Gazula Dasaratha Rama Rao v. State of Andhra Pradesh, the Supreme Court struck

down Section 6(1) of the Madras Hereditary Village Offices Act, 1895 which had required the

Collector to appoint Village Munsiffs from amongst descendants of the last holders of the

offices, Descent being a forbidden ground of classification.

In C.B. Muthamma v. Union of India, the Supreme Court held Rule 8(1) of Indian Foreign

Service (Conduct and Discipline) Rules, 1961 and Rule 18(4) of the Indian Foreign Service

(Recruitment, Cadre Seniority and Promotions) Rules, 1961, as discriminatory against

women.

Rule 8(1) provided that a woman member of the service would obtain permission of the

Government, in writing, before her marriage was solemnised and could be required to resign

from service after her marriage, if the Government was satisfied that her family and domestic

commitments were likely to come in the way of the due and efficient discharge of her duties

as a member of the service. Rule 18(4) stood in her way to promotion to Grade I of the

service.

Article 16

Requirement as to Residence in a State [Article 16(3)]

Clause (3) constitutes an exception to Clause (1) and Clause (2) of Article Clause (3)

empowers the Parliament to make any law prescribing in regard class or classes of

employment or appointment to an office under the Government of, or any local or other

authority within, a State or Union territory, requirement as to residence within that State or

Union territory prior to such employment or appointment.

It may be noted that it is the Parliament and not the Legislature of a State, who can make any

law under Clause (3) of Article 16.

In the exercise of the power conferred by Clause (3) of Article 16, Parliament enacted the

Public Employment (Requirement as to Residence) Act, The Act repealed, all the laws in

force, prescribing any requirement as residence, within a State or Union Territory, for

employment or appointment that State or Union Territory. However, exception was made in

the case of Himachal Pradesh, Manipur, Tripura and Telengana (the area transferred to State

of Andhra Pradesh from the erstwhile State of Hyderabad). This exception was made keeping

in view the backwardness of these areas. It was expire on March 21, 1974.

In Narasimha Rao v. Slate of A.P., the Apex Court struck down Section 3 of the Public

Employment (Requirement as to Residence), Act, 1957, which related to Telengana part of

Andhra Pradesh, as ultra vires the Parliament. Clause (3) of Article 16, the Court explained,

used the word State, which signified State as a unit and not parts of a State as districts or

other units State. Therefore, Parliamentary law could provide for residence in the whole of

Andhra Pradesh and not in Telengana, which was a part of the State.

Reservation of Posts for Backward Classes [Article 16(4)]

Clause (4) of Article 16 expressly permits the State to make provision for reservation of

appointments or posts in favour of any backward class of citizens which, in the opinion of the

State, is not adequately represented in the services under the State.

The expression backward class of citizens in Article 16(4) includes the Scheduled Castes

and the Scheduled Tribes.

This Clause, however, cannot be extended to persons acquiring SC/ST status by voluntary

mobility. Further it was held in Valsamma Paul v. Cochin University, children of inter-caste

married couples, of which one is SC/ST, have been held not entitled to claim reservation

benefit. However, such children can claim relaxation of marks.

Article 16(4) is not an Exception to Article 16(1)

Article 16(4) is an enabling provision. It confers a discretionary power on the State to make

reservation of appointments in favour of backward classes of citizens. It confers no right on

Article 16

10

citizens to claim reservation. Article 16(4) has been held not mandatory. How reservation is

to be made, is a matter of policy.

The Supreme Court in E.V. Chinnaiah v. State of A.P., while striking down the Andhra

Pradesh Scheduled Castes (Rationalisation of Reservation) Act, 2000, ruled that while

reasonable classification is permissible, micro-classification or mini-classification is not.

The State, thus, has no power to sub-divide, sub-classify or sub-group the castes which are

found in the Presidential List of Scheduled Castes, issued under Article 341. The Court

explained that the principle of sub-classification of Backward Class into backward and more

backward was not applicable to Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes.

If a State or Union Territory makes a provision whereunder the benefit of reservation is

extended only to such Scheduled Castes/Tribes which are recognized as such, in relation to

that State/Union Territory, then such a provision would be perfectly valid.

In Indra Sawhney v. Union of India, the Supreme Court ruled that Clause (4) of Article 16

is not an exception to Clause (1) rather it is an instance of classification implicit in and

permitted by Clause (1).

The term reservation in Article 16(4) implies a separate quota which is reserved for a

special category of persons. The very purpose of reservation is to protect the weaker category,

against competition from the open category candidates. Reservation implies selection of less

meritorious person. Thus, grant of relaxation in passing marks to SC/ST candidates in

examinations, would be covered by Article 16(4).

Scope of Article 16(4)

In T. Devadasan v. Union of India, the carry forward rule, regulating reservation of

vacancies for candidates belonging to Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes, was struck

down by the Apex Court, as invalid and unconstitutional.

As a result of the application of the impugued Rule, in the year 1961, out of the 45 vacancies,

actually filled, 29 went to the candidates belonging to Scheduled Castes/Tribes. That came to

about 64% of reservation.

The majority of the Supreme Court following MR. Balaji v. State of Mysore declared that

reservation exceeding 50%, in a single year would be unconstitutional and invalid. The Court

further ruled that, for the purpose of reservation, each year, should be taken by itself and

therefore, there should be no carry forward of the unfilled reserved vacancies.

In State of Kerala v. N.M. Thomas, the Kerala Government framed Rules regulating

promotions from the cadre of lower division clerks to the higher cadre of upper division

clerks, which was made dependent on the passing of a departmental test within two years of

the introduction of this test. Failure to pass the test within two year disentitled the lower

division clerk promotion in future. However, by an Order issued subsequently under the said

Article 16

11

Rule, the members belonging to Scheduled Castes/Tribes were granted a longer period and

were given two extra years to pass the test.

With a view to settle the law, relating to the reservations in an authoritative way, a special

Bench of nine Judges of the Supreme Court, was, for the first time, constituted in Indra

Sawhney v. Union of India, which is popularly known as Mondal Commission case. The

issue was thoroughly examined by the Court in its historical prospective. The majority

opinion on various aspects of reservations may be summarised as follows:

(1)

Until a law is made or rules are issued under Article 309 with respect to reservation in

favour of backward classes, it would always be open to the Executive (Government)

to provide for reservation of appointment/posts in favour of Backward Classes by an

executive order.

(2)

Clause (4) of Article 16 is not an exception to Article 16(1). It is an instance of

classification implicit in and permitted by Clause (1) of Article 16.

(3)

The words provisions for the reservation of appointments/posts in Article 16(4)

include other forms of special provisions like preferences, concessions and

exemptions.

(4)

Clause (4) of Article 16 is exhaustive of the special provision that can be made in

favour of the backward class of citizens.

(5)

Clause (4) of Article 16 is not exhaustive of the concept of reservations. It is

exhaustive of reservations in favour of backward classes alone.

According to the majority view, Article 16(1) permitted the making of reservation of

appointments/posts which should be made only in exceptional situations and wherein

the State is called upon to do so in public interest,

(6)

The word class in Article 16(4) is used in the sense of social class. It is not

antithetical to caste. The Constitution is meant for the entire country and for all time

to come.

(7)

For Identification of backward classes, one has to begin somewhere with some group,

class or section. Neither the Constitution nor the law prescribes the procedure or

method of identification of backward classes. Nor is it possible or advisable for the

Court to lay down any such procedure or method. It must be left to the authority

appointed to identify. It can adopt such method/procedure as it thinks convenient.

(8)

It is not necessary for a class to be designated as a backward class that it is situated

similarly to the Scheduled Castes/Scheduled Tribes.

(9)

The backwardness contemplated by Article 16(4) is mainly social backwardness. It

should not be correct to say that the backwardness under Article 16(4) should be both

social and educational.

Article 16

12

(10)

A backward class cannot be determined only and exclusively with reference to

economic criterion. It may be a consideration or basis along with and in addition to

social backwardness, but it can never be the sole criterion.

(11)

It is permissible for the Government or other authority to identify a backward class of

citizens on the basis of occupation-cum-income without reference to caste.

(12)

There is no constitutional bar to classify the backward classes of citizens into

backward and more backward categories.

The Court held that sub-classification between backward classes and more backward

would be advisable to ensure that the more backward among the backward classes

should obtain the benefits intended for them. If it was not so done then the advanced

section of the backward classes might move away with all the benefits of reservation.

(13)

In order that the backward classes are given adequate representation in the State

services and to ensure that the benefit of reservation reach the poorer and the weakest

section of the backward class, the creamy layer should be excluded in that class, from

claiming the benefit. The Court, therefore, directed the Government of India to

specify the basis of exclusion- whether on the basis of income, extent of holding or

otherwise- of creamy layer.

(14)

The reservation contemplated in Clause (4) of Article 16 should not exceed 50%

However; in extraordinary situation this percentage may be exceeded. But, every

excess over 50% will have to be justified on valid grounds.

(15)

Article 16(4) speaks of adequate representation and not proportionate representation.

(16)

The rule of 50% shall be applicable only to reservations proper, it shall not be, indeed,

cannot be, applicable to exemptions, concessions or relaxations, if any, provided to

Backward Classes under Article 16(4).

(17)

For the purpose of applying the rule of 50%, a year should be taken as the unit and not

the entire strength of the cadre, service or the unit, as the case may be.

(18) The carry forward of unfilled reserved vacancies is not per se unconstitutional. However,

the operation of carry forward rule should not result in breach of 50% rule.

(19)

Article 16(4) does not contemplate or permit reservation in promotions as well. The

reservations are thus confined to initial appointments only.

(20) Reservation for backward classes should not be made in services and position where

merit alone counts.

Justice Ram Nandan Committee-Creamy Layer

In Indra Sawhney v. Union of India, the Supreme Court directed the Government of India

to specify the basis of exclusion whether on the basis of income, extent of holding or

Article 16

13

otherwise of creamy layer. In accordance with this direction, the Government of India

appointed an expert committee known as Justice Ram Nandan Committee, to identify the

creamy layer among the socially and educationally backward classes. The Committee

submitted its report on March 16, 1993, which was accepted by the Government. It was

published in Column 3 of the Schedule to the Government of India, Ministry of Personnel

Department Office Memorandum, and dated 8-9-1993.

In Ashok Kumar Thakur v. State of Bihar, the Supreme Court quashed the criteria laid

down by the States of Bihar and Uttar Pradesh for identifying the creamy layer and

excluding the affluent sections of the Backward Classes for the purposes of job reservation.

The Supreme Court held that the conditions in addition to those laid down in Mandal case,

for applying the rule of exclusion laid down by the States had no nexus with the object sought

to be achieved and were arbitrary, and hence violative of Articles 16(4) and 14 as also against

the law laid down in Mandal case.

A three-Judge Bench of the Supreme Court in Indra Sawhney v. Union ofIndia ruled that

non-exclusion of creamy layer in backward classes was violative of Articles 14 and 16(1) and

also of Article 16(4).

Reservation in Super-Specialities

In Indra Sawhney v. Union of India, the majority of the Supreme Court had opined that

there were certain services and positions where, either an account of the nature of duties

attached to them or the level (In the hierarchy) at which they were obtained, merit alone

would count. It, therefore, meant that the rule of reservation would not be applied in cases of

super-specialities.

In K. Duraisamy v. State of Tamil Nadu, the Supreme Court in this respect, observed:

It is by now a proposition well settled that at the super speciality level in particular and even

at the Post-Graduate level reservations of the kind known as protective discrimination in

favour of those considered being backward should be avoided as being not permissible.

Backward Classes U/A 16(4)

There was an overwhelming majority in the nation that was still backward socially,

economically, educationally, and politically. These victims of entrenched backwardness

comprise the present scheduled castes (SC), scheduled tribes (ST) and other backward classes

(OBC). Even though, these classes are generically the "Backward Classes, the nature and

magnitude of their backwardness are not the same.

The words ' "backward class of citizens" occurring in Article 16 (4) are neither defined nor

explained in the Constitution though the same words occurring in Article 15 (4) are followed

by a qualifying phrase, "Socially and Educationally'' backward classes.

Article 16

14

In the course of debate in the Parliament on the intendment of Article 16 (4), Dr. B.R.

Ambedkar, expressed his views that backward classes are which nothing else but a

collection of certain castes.

Incidentally, it is also necessary to point out that the Supreme Court in all its decisions on

reservation has interpreted the expression `backward classes' in Article 16 (4) to mean the

"socially and educationally" backward. It also emphatically rejected "economic

backwardness" as the only or the primary criterion for reservation under article 16 (4) and

observed that economic backwardness has to be on account of social and educational

backwardness. The true meaning of this expression has been considered in a number of cases

by the Supreme Court starting from Balaji to Indira Sawhney.

(1) In M.R. Balaji v. State of Mysore, it was held that the caste of a group of persons cannot

be the sole or even predominant factor though it may be a relevant test for ascertaining

whether a particular class is backward or not. The two tests should be conjunctively

applied in determining backward classes: one, they should be comparable to the Schedule

Castes and Schedule Tribes in the matter of their backwardness; and, two, they should satisfy

the means test, that is to say, the test of economic backwardness laid down by the State

government in the context of the prevailing economic conditions. Poverty, caste, occupation

and habitation are the principal factors contributing to social backwardness.

(2) In R. Chitralekha and Anr. v. State of Mysore and Ors. and Triloki Nath v. J & K

State and K.C. Vasanth Kumar v. Karnataka

The Apex Court explaining the meaning of Class observed that The quintessence of the

definition of Class is that a group of persons having common traits or attributes coupled

with retarded social, material (economic) and intellectual (educational) development in the

sense not having so much of intellect and ability will fall within the ambit of 'any backward

class of citizens' under Article 16 (4) of the Constitution.

(3) Further in R. Chitralekha v. State of Mysore, it was stated that:

...what we intend to emphasize is that under no circumstances a "class" can be equated to a

"caste", though the caste of an individual or a group of individual may be considered along

with other relevant factors in putting him in a particular class.

(4) In State of Andhra Pradesh v. P. Sagar, it has been observed that:

The expression "class" means a homogeneous section of the people grouped together because

of certain likenesses or common traits and who are identifiable by some common attributes

such as status, rank, and occupation, residence in a locality, race, religion and the like. In

determining whether a particular section forms a class, caste cannot be excluded altogether.

But in the determination of a class a test solely based upon the caste or community cannot

also be accepted.

Article 16

15

(5) In Triloki Nath v. J & K State -Shah, J., speaking for the Constitution Bench has

reiterated the meaning of the word 'class' as defined in the case of Sagar and added that "for

the purpose of Article 16 (4) in determining whether a section forms a class, a test solely

based on caste, community, race, religion, sex, descent, place of birth or residence cannot be

adopted, because it would directly offend the Constitution.

The expression backward class is not used as synonymous with backward caste or

backward community. The members of an entire caste or community may in a social,

economic and educational scale of values at a given time be backward and may on that

account be treated as a backward class, but that is not because they are members of a caste or

community, but because they form a class.

(6) In A. Peeriakaruppan, etc. v. State of Tamil Nadu

The Supreme Court observed that A caste has always been recognised as a class. If the

members of an entire caste or community at a given time are socially, economically and

educationally backward that caste on that account be treated as a backward class. This is not

because they are members of that caste or community but because they form a class.

(7) Chief Justice Ray in Kumari K.S. Jayasree and Anr. v. The State of Kerala and

Anr. was of the view that In ascertaining social backwardness of a class of citizens it may

not be irrelevant to consider the caste of the group of citizens. Caste cannot however be made

the sole or dominant test...

(8) In Indira Sawhney and Ors. Vs. Union of India and Ors., the Court observed that:The meaning of the expression backward classes of citizens is not qualified or restricted by

saying that it means those other backward classes who are situated similarly to Scheduled

Caste and/or Scheduled Tribes. Backwardness being a relative term must in the context be

judged by the general level of advancement of the entire population of the country or the

State, as the case may be.

There is adequate safeguard against misuse by the political executive of the power u/Art.

16(4) in the provision itself. Any determination of backwardness is neither a subjective

exercise nor a matter of subjective satisfaction. The exercise is an objective one. Certain

objective social and other criteria have to be satisfied before any group or class of citizens

could be treated as backward. If the executive includes, for collateral reasons, groups or

classes not satisfying the relevant criteria, it would be a clear case of fraud on power.

Caste neither can be the sole criterion nor can it be equated with 'class' for the purpose of

Article 16 (4) for ascertaining the social and educational backwardness of any section or

group of people so as to bring them within the wider connotation of 'backward class'.

Nevertheless 'caste' in Hindu society becomes a dominant factor or primary criterion in

determining the backwardness of a class of citizens.

Unless 'caste' satisfies the primary test of social backwardness as well as the educational and

economic backwardness which are the established and accepted criteria to identify the

Article 16

16

'backward class', a caste per se without satisfying the agreed formulae generally cannot fall

within the meaning of 'backward class of citizens' under Article 16 (4), save in given

exceptional circumstances such as the caste itself being identifiable with the traditional

occupation of the lower strata indicating the social backwardness. And Class has occupation

and Caste nexus; it is homogeneous and is determined by birth. It further

approved Chitralekha case.

(9) Further in case of Jagdish Negi v. State of U.P it was held Backwardness is not a static

phenomenon. It cannot continue indefinitely and the State is entitled to review the situation

from time to time.

Article16(4) & Article 335

Article 335: provides that the claims of the members of the SCs and STs shall be taken into

consideration, consistently with the maintenance of efficiency of administration in the

making of appointments in services and posts in connection with the affairs of the Union or

of a State.

There has been some debate as to whether Art.335 had any limiting effect on the power of

reservation conferred by Art.16 (4). The nine judge bench of the Supreme Court in Indira

Sawhney considered the argument that the mandate of Art.335 implied that reservation

should be read subject to the qualification engrafted in Art.335 i.e. consistently with the

maintenance of efficiency of administration. Dealing with the argument majority framed an

issue as to whether reservations were anti-meritarian? The majority then observed that may

be efficiency, competence and merit are not synonymous concepts; may be it is wrong to treat

merit as synonymous with efficiency in administration and that merit is but a component of

the efficiency of an administration.

Even so the relevance and significance of merit at the stage of initial recruitment cannot be

ignored. It cannot also be ignored that the very idea of reservation implies selection of a less

meritorious person. At the same time, we recognise that this much cost has to be paid, if the

constitutional promise of social justice is to be redeemed. We also firmly believe that given

an opportunity, members of these classes are bound to overcome their initial disadvantages

and would compete with-and may in some cases, excel members of open competitor

candidates. It is undeniable that nature has endowed merit upon members of backward classes

as much as it has endowed upon members of other classes and what is required is an

opportunity to prove it.

But in case of Article 16, Article 355 would be relevant. It may be permissible for the

government to prescribe a reasonably lower standard for scheduled castes/Scheduled

tribes/backward classes consistent with the requirements of efficiency of administration. It

would not be permissible not to prescribe any such minimum standard at all. While

prescribing the lower minimum standard for reserved category, the nature and duties attached

to the post and the interest of the general public should also be kept in mind. While on Article

355, we are of the opinion that there are certain services and positions where merit alone

Article 16

17

counts. In such situations, it may not be advisable to provide for reservations. For example

technical post in Research and Development organisations/departments/institutions,

superspecialities in medicine, engineering etc.

Article 16(4) of the Indian Constitution and the Hohfeldian concept of

Rights:

Part III of the Indian Constitution covers the Fundamental Rights of the citizens of the

country. All these Fundamental Rights indicate that all the citizens are equally treated by the

nation irrespective of caste, sex and creed. Article 16(4) also, no doubt, fall within Part III of

the Constitution comprising the fundamental rights. Article 16(4) of the Indian Constitution

states that Nothing in this article shall prevent the State from making any provision for the

reservation of appointments or posts in favour of any backward class of citizens which, in the

opinion of the State, is not adequately represented in the services under the

State. Article 16(4) provides for reservation for Backward Classes in cases of inadequate

representation in public employment. Article 16(4) is enacted as a remedy for the past

historical discriminations against a social class. The object in enacting the enabling

provisions like Articles 16(4), 16(4-A) and 16(4-B) is that the State is empowered to identify

and recognize the compelling interests. If the State has quantifiable data to show

backwardness and inadequacy then the State can make reservations in promotions keeping in

mind maintenance of efficiency which is held to be a constitutional limitation on the

discretion of the State in making reservation as indicated by Article 335.

The word Right which we use in our general parlance or in our day to day life, not even we

but also our Judges and in our legal system differs a lot from Hohfelds concept of

Right. Hohfeld's analysis of rights lies in the descriptive exercise of the legal positions which

are connected with each other by means of logical relations of entailment and negation.

Hohfeld's ambition was to provide a conceptual understanding for our use of right, duty etc.

in practice, thus facilitating a better understanding of the nature of our rights. Thus in the

Hohfeldian analysis the term right involves four strictly fundamental legal relationsright( or claim), privilege, power and immunity. He identified eight fundamental

concepts that allow one to describe any legal position. These concepts are duty, claim, liberty,

no claim, power, liability, disability, and immunity. Hohfeld explained how these concepts

logically related to one another through what he called correlation and opposition.

Our Fundamental Rights are generally called as negative rights because they limit the power

of the State to exercise over its citizens and thus the citizens gets a upper hand, and the State

cannot interfere with any of the rights of the citizens as mentioned under part III of the Indian

Constitution.

If we look into the debate on negative rights and positive rights, we find that, negative rights

are considered to be those rights which oblige others to refrain from interfering with

someone's attempt to do something and positive rights are those which impose a

moral obligation on a person to do something for someone. Now, if we take Article 16(4) into

consideration, it comes within the purview of Part III of the Indian Constitution and so it

must be considered to be negative right. But a bare reading of the text clearly shows that it

empowers the State to make provisions for the backward classes of the State. Thus, if we

follow the debate on negative rights and positive rights, then it is quite clear that, though

Article 16

18

Article 16(4) falls within Part III of the Indian Constitution, it cannot be called as a negative

right but its a positive right.

As Article 16(4) falls within the purview of Part III of the Constitution, it is called as a

fundamental right of the citizen. The first impression which comes into our mind, when we

says that Article 16(4) is a Fundamental Right, is that, in Hohfeldian Concepts it must be a

claim right. But a bare reading of the Provision reflects in our mind that the Right which is

given under Article 16(4) is actually a privilege which is conferred into the hands of the State.

Also if we analyse the decision of the Court in the case of P&T Schedule Caste/ Tribe

Employees Association v. U.O.I, in which the Court has observed that Article 16(4) is only

an enabling clause and no writs can be issued ordinarily compelling the government to make

reservation, we are clear that Article 16(4) is not a Claim right. As we know that, the Jural

correlative of Claim Right is Duty, if the backward classes would having a Claim right, then

the State would have under a Duty to provide reservation. But the decision of the Court in the

abovementioned case, clearly says that, the State is under no duty to provide reservation on

the wish of the Backward classes. Thus, as there is no correlative duty on the part of the State,

it is quite clear that, Article 16(4) is not a claim right for the backward classes of the society.

Hohfeld described privilege or liberty as, to have a liberty to engage in a certain action is to

be free from any duty to eschew the action, likewise, to have a liberty to abstain from a

certain action is to be free from any duty to undertake the action. Like any right, each liberty

is held by a specific person or group of persons against another specific person or group of

persons. The person against whom the liberty is held has a no-right concerning the activity or

state of affairs to which the liberty pertains.

Under Hohfeldian concept, the jural correlative and jural opposite of Privilege is No-right

and Duty. When Article 16(4) gives privileges to the State in providing reservation, it means

that the class which is favoured by this reservation has no-right to claim and at the same time

the State is also under no Duty to perform what it has been asked to do. This very concept of

privilege has been clearly proved by the decision of the Court in the case of P&T Schedule

Caste/ Tribe Employees Association v. U.O.I., in which the Court clearly held that the State

is under no duty to give reservation.

Under Hohfeldian concept of rights, Power denotes ability in a person to alter the existing

legal condition, whether of oneself or of another, for better or for worse. The correlative of

power is liability which denotes the position of a person whose legal condition can be so

altered.

Now, if we construe the term power as stated in Indra Sawhney v. U.O.I with that of the

term power as defined by Hohfeld, we will see that a lot of conflict will arise between the

two. If the State has power under clause (4) of Article 16 of the Constitution, then in

Hohfeldian sense it will mean that the State is vested with all the power of altering the

existing legal condition. In contrast it means that, the community, i.e. the legal condition of

the backward class is easily susceptible. Also, it has been mentioned that power itself doesnt

have any correlative duty attached to it. This also means that the State is under no duty to act,

which is to provide reservation to the backward classes.

Article 16

19

Let us go back to the debate over negative rights and positive rights, which we discussed

earlier. We found that, though Article 16(4) falls within the purview of Part III of the

Constitution, it is not a negative right in contrast that Fundamental Rights are negative rights,

but its a positive right which the State uses to provide reservation to the backward classes of

the community. Now, this was concluded from a bare reading of the provision which reads as

Nothing in this article shall prevent the State from making any provision for the reservation

of appointments or posts in favour of any backward class of citizens which, in the opinion of

the State, is not adequately represented in the services under the State. Now, lets analyse the

debate over positive rights and negative rights while referring to the interpretation given by

our Supreme Court while defining the scope of Article 16(4). The Court held that, the

provision gives power to the State to make reservation in favour of the backward classes of

the society. Thus, the debate over negative and positive rights clearly states that Privileges

and powers cannot be negative rights; and privileges, powers, and immunities cannot be

positive rights. For example the right to enter into a binding agreement, and the right to veto a

bill, are neither negative nor positive. Thus, we have seen that, it is neither a positive right nor

a negative right.

If this is the power which the Constitution provides to the State under Article 16(4), then

there will be a great conflict. The main conflict which will arise is that, whether we should go

by the interpretation which was made by the Court while defining the Scope of the provision

or we have to go by the provision itself which is given under part III of the Constitution.

From the above discussions, we have seen that, the State is either having a privilege or power

in Hohfeldian concept and thus it is not bound by the people of the backward class to provide

any benefit to the particular community, for which the provision was added into our

Constitution.

Thus, if we would look at the provision of Article 16(4) of our Constitution in terms of

Hohfeldian Concept of Rights, we will find that it is not a Fundamental Right of the Citizens.

The very nature of the Fundamental Rights is to limit the power of the State and to give the

Citizens of the State an upper hand. But from the above discussions we have seen that, it is

the State which is incurring power from the very provision of the Constitution and it is in

contradiction to the very nature of Fundamental Rights.

Thus, we can conclude that, if we look at the provision of Article 16(4) of the Constitution,

from Hohfeldian Concept of Rights, then Article 16(4) of our Constitution, though its come

within the purview of part III of the Constitution, is not a Fundamental Right of the Citizen.

But, from a general understanding of Rights and as understood by every person, Article 16(4)

is still considered as a Fundamental Right. So, we can say that the Hohfeldian Concept of

Rights is an abstract notion and we cannot apply it into any statutes e.g., like our

Constitution, and if we would try to apply this to any working legal system then everything

will go haywire.

Article 16

20

Reservation in PromotionSeventy-seventh Amendment, 1995[Article

16(4A)]

In Indra Sawhney v. Union of India, after taking into consideration all the circumstances,

the Court said that Article 16(4) did not contemplate or permit reservation in promotions.

This question, the Court said, had not to be answered on a reading of Article 16(4) alone but

on a combined reading of Article 16(4) and Article 335.

The Court observed that while it was certainly just to say that a handicap should be given to

backward classes of citizens at the stage of initial appointment, but it would be a serious and

unacceptable inroad into the rule of equality of opportunity to say that such a handicap should

be provided at every stage of promotion throughout their career.

The above rifle has been modified as regards the members belonging to the Scheduled Castes

and the Scheduled Tribes, by the Constitution (Seventy-seventh Amendment) Act, 1995.

The 77th Amendment, 1995 has been upheld by the Supreme Court in Commissioner of

Commercial Taxes, A.P. Hyderabad v. G. Sethumadhava Rao.

Exclusion of 50% Ceiling w.r.t. Carry Forward Reserved Vacancies [Article

16(4B)]

In Indra Sawhney v. Union of India, the majority had ruled that operation of carry forward

rule should not result in breach of 50% rule. This while would no more be followed after the

enactment of the Constitution (Eighty-first Amendment) Act, 2000.

This new Clause (4B) enables the State to carry forward the unfilled reserved vacancies to be

filled in any succeeding years so as to remove the backlog, notwithstanding the rule of 50%

ceiling.

Reservation in Promotion: Catch-up Rule Negated- 85th Amendment, 2001

A five-Judge Constitution Bench of the Supreme Court, in Ajit Singh v. State of Punjab,

ruled that the primary purpose of Article 16(4) and Article 16(4A) was to provide due

representation to certain classes in certain posts.

The Apex Court further observed that the rule of reservation gave accelerated promotion, but

it did not give the accelerated consequential seniority. The Court explained that a reasonable

balancing of the rights of general candidate and roster candidate would be achieved by

following the catch-up rule.

According to this rule if in case any senior general candidate at level 2 reaches level 3 before

the reserved candidate (roster point promotee) at level 3 goes further up to level 4, in that

case the seniority at level 3 has to be modified by placing such a general candidate above the

roster promotee reflecting their inter Se seniority at level 2.

Article 16

21

To negate the effect of the above judgments, Article 16(4A) has been amended by the

Constitution (85th Amendment) Act, 2001. In the amended Clause (4A) of Article 16, in

place of the words in matter of promotion to any class, the words in matter of promotion

with consequential seniority to any class have been substituted.

Principles of Reservation do not apply to Isolated Post

A five-Judge Constitution Bench of the Supreme Court in Post Graduate Institute of

Medical Education and Research, Chandigarh v. Faculty Association, reiterated with

approval, the view held in Chakradhar Paswan v. State of Bihar and ruled that there would

have to be plurality of posts for reservation. Allowing a review petition moved by the Faculty

Association of the P.G.I., Chandigarh, and the Court held that any attempt at reservation, by

whatever means in a single post cadre, even through the device of rotation of a roster, was

bound to create 100% reservation in such cadre. Holding that there was need for

reservation for the members of the SCs/STs and OBCs, and that such reservation was not

confined to the initial appointment in a cadre but also to the appointment In promotional post,

the Court explained: In making reservations for the backward classes, the State cannot

ignore the fundamental rights of the rest of citizens.

Earlier, the Supreme Court in Union of India v. Madhav Gajanan Chaubal, had held that a

rule providing reservation in a single post would not be unconstitutional.

A Division Bench of the Supreme Court in State of Karnataka v. Govindappa, relied upon

the decision in PGI case and held that in the cadre of lecturers single and isolated posts in

respect of different disciplines could exist as a separate cadre. Since there was no scope for

inter- changeability of posts in the different disciplines, each single post in a particular

discipline had to be treated as a single post for the purpose of reservation within the meaning

of Article 16(4). Rule of reservation, therefore, would not apply to such single isolated post,

the Court ruled.

Offices under a Religious or Denominational Institution [Article 16(5)]

Clause (5) of Article 16 is the third exception to the general rule of equality of opportunity

contained in Article 16 (1) as also Clause (2). Clause (5) provides that a law may prescribe

that the incumbent of an office in connection with the affairs of any religious or

denominational institution, or any member of the governing body thereof, shall be a person

professing a particular religion or belonging to a particular denomination. It, thus, permits

that an office in connection with the affairs of Hindu religion or Hindu religious

denomination can be held only by a Hindu, if it is so provided in the document relating to it.

Likewise, any office under a Muslim institution may be required to be held only by a Muslim.

This exception may be read with the fundamental right to freedom of religion contained in

Articles 25 to 28 and the right of the minorities under Articles 29 and 30.

Article 16

22

Equal Pay for Equal Work

In Randhir Singh v. Union of India, the Supreme Court enunciated the principle of equal

pay for equal work. The Court observed that it was true that the principle of equal pay for

equal work was not expressly declared by the Constitution to be a fundamental right. But, it

certainly was the constitutional goal. The Court held that this principle could be deducted

from Articles 14 and 16, when these provisions were construed in the light of the Preamble

and Article 39(d) of the Constitution. The Court further laid down that the principle could be

properly applied to cases of unequal scales of pay based on no classification or irrational

classification.

Again, in Daily Rated Casual Labour (P & T) v. Union of India, the Supreme Court held

that the daily rated casual labourers in P & T Department, who were doing the similar work

as done by the regular workers, were entitled to minimum pay in the pay scale of the regular

workers plus dearness allowance but without increments. Classification of employees into

regular employees and casual employees for the purpose of payment of less than minimum

pay, the Court held, was violative of Articles 14 and 16(1) of the Constitution. The Court

further declared that denial to them of minimum pay amounted to exploitation of labour. The

Government could not take advantage of its dominant position. Rather, it should be a model

employer. Denial of equal pay only on the basis of source of recruitment has been held

improper.

In Federation of All India Customs and Central Excise Stenographers (F.A.I.C. &

C.E.S.) v. Union of India, on the basis of the recommendations of the Third Pay

Commission, 1973, the Central Government fixed different pay scales for Stenographers

Grade I working in Central Secretariat and those attached to the Heads of Subordinate

Offices. While, the former were given higher grade, the latter were granted lower scale of

pay.

The Supreme Court, upheld the differentiation in the pay scales and ruled that although

equal pay for equal work was a fundamental right, but equal pay must depend upon the

nature of the work done and that it could not be judged by the mere volume of work. There

might be qualitative difference as regards reliability, responsibility and confidentiality.

Functions might be the same but the responsibilities would make a difference. The rule of

equal pay for equal work, is a concomitant of Article 14, but the Court explained that

equal pay for unequal work would be a negation of that right. If the differentiation had been

sought to be justified in view of the nature and the type of the work done, then, on intelligible

basis, the same amount of physical work might entail different quality of work. It would,

therefore, vary, depending upon the nature and culture of employment. Although the duties of

the petitioners and their Secretariat counterparts were identical, their functions were not

identical. The Supreme Court, therefore, justified the differentiation on the ground of

dissimilarity of the responsibility, confidentiality and the relationship with public, etc.

Article 16

23

Granting different pay scales to employees belonging to same cadre, based on educational

qualifications has been held not discriminatory. Likewise, distinction between trained and

untrained lecturers, for purposes of prescribing pay scales, has been held valid and

reasonable.

The rule of equal pay for equal work is not always easy to apply. There may be inherent

difficulties in comparing and evaluating work done by different persons in different

organisations or even in the same organisation. It is not an abstract doctrine. The judgment of

administrative authorities concerning the responsibilities which attach to the post and the

degree of reliability expected of an incumbent, would be a value judgment of the authority

concerned, which if arrived at bona fide, reasonably and rationally, was not open to

interference by the Court. The nature of world the sphere of work, duration of work and other

special circumstances, if any, attached to the performance of duties, would have also to be

taken into consideration while working the doctrine of equal pay for equal work. The rule

has been held not applicable where there was difference in the mode of recruitment,

qualifications and promotion among persons though holding same posts and performing

similar work.

Again, pay parity, between employees of State Government and Central Government cannot

be claimed on the basis of identity of designation. Also, temporary Ad hoc, daily wagers or

casual workers like N.M.Rs., have been held not entitled to equal pay with regularly

employed permanent staff in the establishment.

In S.C. Chandra v. State of Jharkhand, the Apex Court held that teachers in schools could

not be equated with clerks in Government Corporation or State Government.

The Court also referred to the decision in State of T.N. v. M.R. Alagappan, wherein the

Apex Court observed that substantial similarity in duties and responsibilities and

interchangeability of posts, might not also necessarily attract, the principle of equal pay for

equal work when there were other distinguishing features.

ARTICLE 16 AS A BUNDLE OF CONTRADICTIONS

Article 16 of the Constitution of India is a bundle of contradictions, as on the one hand it

deals with equality of opportunity in matters of public employment, and, on the other, it

enables the government to provide for reservation in public employment.

Article 16 of the Constitution is part of the Fundamental Rights and provides for equality in

the matters of employment in public employment. Many people feel that this Article, instead

of equality in these matters, perpetuates the inequalities and offers a framework of

contradiction. The Fundamental Rights should ideally provide the measures vide which the

equality is ensured but the exceptions provided to this right overweigh the right provided.

Article 16 provides that there shall be equality of opportunity for all citizens in the matters of

Article 16

24

employment or appointment to any office under the State. This Article also provides that no

citizen shall be ineligible for any office or employment under the State on grounds only of

religion, race, caste, sex, descent, and place of birth or any of them.

After having stated the above, several exceptions are also provided for. Place of residence

may be laid down by the legislature as a condition for particular classes of employment or

appointment in any State or any local authority. Further, the State may reserve any post or

appointment in favour of any backward class of citizens, who, in the opinion of the State, are

not adequately represented in the services under that State. In addition, the offices connected

with the religious or denominated institutions may be reserved for the members practicing

that particular religion.

The most important and controversial exception pertains to the provisions of Article 16(4)

relating to the claims of the members of the Scheduled Caste and Scheduled Tribe

communities in the matters of appointment to the services and posts under the Union and the

States, to be consistent with efficiency in administration as far as possible (Article 335). The

Supreme Court has held that while the provisions of Article 16(4) are without any limitation

upon the power of reservation, yet it has to be read with the provisions of Article 335 for

maintenance of efficiency in administration. The Apex Court also held that the total

reservation under Article 16(4) should not exceed 50 per cent.

Detailed study of the provisions of the Article 16 reveals that while originally this Article

aimed at protecting the rights of common man with regard to equality of opportunity but

gradually, due to the need felt by the government to extend the benefit of reservation to the

other backward classes and also the political considerations, its focus has now shifted to

providing the benefit of reservation to the backward classes and the SC/ST. But one thing has

been confirmed that the extension of the benefit cannot be arbitrary.

Various pronouncements of the Supreme Court of India during the past almost six decades

have plugged the gaps in the provisions of this Article and also provided a standard

framework for extending the benefit of reservation in future to any other categories. The

measures that looked to be controversial initially have also been settled by the judgments of

the highest court of law in the country.

AN EPILOGUE

The reservation policy in India in all sectors has become a disturbing and cyclical process.

Initially with the introduction of constitution it provided reservation for only SCs and STs

but later on OBC were included and now the other minorities are demanding reservation as

well, which would ultimately lead to a situation where the seats left for the majority would

not be proportional with their population. This therefore, becomes an unending issue, rather

than an equal opportunity issue.

Its not that only developing or underdeveloped countries are facing sociological problems

because these problems still persist in the most developed nation in the world like that of

USA. But in USA there is no reservation policy as such and there is an affirmative action

Article 16

25

program for the minorities and especially for the African-Americans. India being a

developing country is slogging in almost all facets to achieve its 2020 mission but for that

there is a serious need for reconsideration of the reservation policy in India because the

reservation policy compromises with the efficiency of a Country by not sincerely recognizing

the merits of backward classes which therefore hamper the development of a country.

BIBIOGRAPHY

BOOKS

Kumar, Narender. Constitutional Law, 1st Edition. Faridabad: Allahabad Law

Agency, 2011

Dr. J.N. Pandey The Constitutional Law of India, 48 th Edition. Central Law

Agency.

Article 16

26

M.P. Jain. Indian Constitutional Law.

WEBSITES

<http://www.competitionmaster.com/Category.aspx?ID=e3d407c1-73b7-43dfae5c-0c449475070c>

<http://www.lawyersclubindia.com/articles/Article-16-4-of-IndianConstitution-and-Hohfeldian-Concepts-1847.asp>

<http://www.goforthelaw.com/articles/fromlawstu/article60.htm>

You might also like

- Reflections on 30 Years of the Asian Development Bank Administrative TribunalFrom EverandReflections on 30 Years of the Asian Development Bank Administrative TribunalNo ratings yet

- Article 16Document26 pagesArticle 16harrybrar3100% (3)

- Indian Constitution's Article 16 on Equality in Public EmploymentDocument32 pagesIndian Constitution's Article 16 on Equality in Public EmploymentR.Sowmya Reddy100% (1)

- Article 16 Consti ProjectDocument27 pagesArticle 16 Consti ProjectR.Sowmya ReddyNo ratings yet

- Article 16Document14 pagesArticle 16Milan SharmaNo ratings yet

- Constitution Project - Equality of OpportunityDocument21 pagesConstitution Project - Equality of OpportunitySmriti SrivastavaNo ratings yet

- Constitution ProjectDocument21 pagesConstitution ProjectSmriti SrivastavaNo ratings yet

- Chandni PT 2Document44 pagesChandni PT 2chawlanitin0210No ratings yet

- Article 16Document6 pagesArticle 16DebarchanaNo ratings yet

- Equality in Public EmploymentDocument16 pagesEquality in Public EmploymentMIMANSA PUJARINo ratings yet

- constitutionDocument31 pagesconstitutionrtjadhav158721804No ratings yet

- Article 16 of The Indian Constitution ConstiDocument11 pagesArticle 16 of The Indian Constitution Constiporetic617No ratings yet

- Project On Constituional Governance 2 Doctrine of PleasureDocument28 pagesProject On Constituional Governance 2 Doctrine of PleasureAnamikaSingh100% (1)

- 0 - 96520339 Article 16Document27 pages0 - 96520339 Article 16KashishBansalNo ratings yet

- Fundamental Rights (4)—Right to Equality (iii) SynopsisDocument65 pagesFundamental Rights (4)—Right to Equality (iii) SynopsisAnushka RungtaNo ratings yet

- C.R.P. 292 2021 Sacked EmployeesDocument31 pagesC.R.P. 292 2021 Sacked EmployeesSyed AhmadNo ratings yet

- Consti AssignmentDocument11 pagesConsti Assignmentshivam tiwariNo ratings yet

- Article 16 (4) VN ShuklaDocument5 pagesArticle 16 (4) VN ShuklaYashashree MahajanNo ratings yet

- Public Employment FootnotesDocument9 pagesPublic Employment FootnotesPriyadarshan NairNo ratings yet

- Critical CommentDocument8 pagesCritical Commentvarun v sNo ratings yet

- Andhra Pradesh vs. Vijay Kumar & Anr, 1995 AIR 1648 Facts of The CaseDocument5 pagesAndhra Pradesh vs. Vijay Kumar & Anr, 1995 AIR 1648 Facts of The CaseKeshav AggarwalNo ratings yet

- Article 16 of Indian Constitution: Dr. Poonam Nathani Dayanand College of Law, LaturDocument30 pagesArticle 16 of Indian Constitution: Dr. Poonam Nathani Dayanand College of Law, LaturDattaNo ratings yet

- BOCL ProjectDocument13 pagesBOCL ProjectPrashant KushwahNo ratings yet

- Randhir Singh vs Union of India: Equal pay for equal workDocument12 pagesRandhir Singh vs Union of India: Equal pay for equal workSachin KumarNo ratings yet

- ReservationDocument34 pagesReservationAjay KhedarNo ratings yet

- Case LawsDocument26 pagesCase LawsAshutosh PrasadNo ratings yet

- Name - Pooja Singh. Class - Bcom LLB 9 SEM Section - D ROLL NO. - 181/16 University Roll No. - 14697 Assigned Teacher - Sanjeev SirDocument13 pagesName - Pooja Singh. Class - Bcom LLB 9 SEM Section - D ROLL NO. - 181/16 University Roll No. - 14697 Assigned Teacher - Sanjeev SirpoojaNo ratings yet

- Reservation in Promotions in IndiaDocument19 pagesReservation in Promotions in IndiaAiswarya MuraliNo ratings yet

- 1) Anuj Garg Vs Hotel Association of India: Article 15Document26 pages1) Anuj Garg Vs Hotel Association of India: Article 15UriahNo ratings yet

- Indian-Constitution GTU Study Material E-Notes Unit-5 25102019114854AMDocument5 pagesIndian-Constitution GTU Study Material E-Notes Unit-5 25102019114854AMDharamNo ratings yet

- Reservation in ServiceDocument266 pagesReservation in ServiceNareshKumar_TNo ratings yet

- Professional Ethics 2Document5 pagesProfessional Ethics 2Anamika VatsaNo ratings yet

- Right To Equality in India:analysisDocument15 pagesRight To Equality in India:analysisVineetNo ratings yet

- Constitutional ArticlesDocument26 pagesConstitutional Articleskoyelll915No ratings yet

- 21bbl034 LDIOS ProjectDocument24 pages21bbl034 LDIOS ProjectGAURAVI TALWARNo ratings yet

- Valsamma Paul v. Cochin UniversityDocument19 pagesValsamma Paul v. Cochin UniversityKritika NagpalNo ratings yet

- The Doctrine of Twin TestDocument3 pagesThe Doctrine of Twin TestVarun Raj Nair0% (1)

- Article 16 (4) and 335Document19 pagesArticle 16 (4) and 335husainNo ratings yet

- NLIU Professional Ethics on Rule making powers under Advocates' Act 1961Document19 pagesNLIU Professional Ethics on Rule making powers under Advocates' Act 1961Yash VermaNo ratings yet

- Article 16-18 Indian Constitution NewDocument19 pagesArticle 16-18 Indian Constitution NewHimanshu SharmaNo ratings yet

- Reservations, Equality and The Constitution-The Early CasesDocument4 pagesReservations, Equality and The Constitution-The Early CasesRadheyNo ratings yet

- Punjab HC upholds experience requirement for Sub-Inspector promotionDocument6 pagesPunjab HC upholds experience requirement for Sub-Inspector promotionLeo KhanNo ratings yet

- LSPE CaseDocument18 pagesLSPE Caseyogesh kumarNo ratings yet

- Whether Proportional Representation Is Adequate RepresentationDocument10 pagesWhether Proportional Representation Is Adequate Representationakira menonNo ratings yet

- Case Comment - M Nagraj v. Union of IndiaDocument9 pagesCase Comment - M Nagraj v. Union of IndiaRohit kumarNo ratings yet

- Affirmative Action LawDocument11 pagesAffirmative Action LawVed VyasNo ratings yet

- 14 Chapter 9 PDFDocument46 pages14 Chapter 9 PDFDwijen JoshiNo ratings yet

- Article 16 of the Indian Constitution: Equality of Opportunity vs ReservationDocument1 pageArticle 16 of the Indian Constitution: Equality of Opportunity vs ReservationSatish SinghNo ratings yet

- Article 16,17 and 18Document50 pagesArticle 16,17 and 18GokulNo ratings yet

- CL Vol-3 Issue-III 21112022Document21 pagesCL Vol-3 Issue-III 21112022Sadaqat YarNo ratings yet

- Istj 175Document5 pagesIstj 175Manager PersonnelkptclNo ratings yet

- 117th Amendment COI Manish RajDocument5 pages117th Amendment COI Manish RajYuvan KumarNo ratings yet

- Case Digest: ABAKADA GURO PARTY LIST OFFICERS v. CESAR V. PURISIMADocument3 pagesCase Digest: ABAKADA GURO PARTY LIST OFFICERS v. CESAR V. PURISIMAAnton Ric Delos ReyesNo ratings yet

- Ra 9347Document5 pagesRa 9347Mary Eileen AngNo ratings yet

- State of Kerala & Another Vs N.M. Thomas & OTHERS, 1975Document5 pagesState of Kerala & Another Vs N.M. Thomas & OTHERS, 1975DebashritaNo ratings yet

- Professional Ethics SessionDocument21 pagesProfessional Ethics SessionbashiNo ratings yet

- SSRN-id3813722Document11 pagesSSRN-id3813722samarthNo ratings yet

- Manual on the Character and Fitness Process for Application to the Michigan State Bar: Law and PracticeFrom EverandManual on the Character and Fitness Process for Application to the Michigan State Bar: Law and PracticeNo ratings yet