Professional Documents

Culture Documents

science: Auditing Urinary Catheter Care

Uploaded by

Nissa ErLinaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

science: Auditing Urinary Catheter Care

Uploaded by

Nissa ErLinaCopyright:

Available Formats

p35-40w20_A&S Template 13/01/2012 16:24 Page 35

Art &science

If you would like to contribute to the Art & science

section, email gwen.clarke@rcnpublishing.co.uk

The synthesis of art and science is lived by the nurse in the nursing act

JOSEPHINE G PATERSON

Auditing urinary catheter care

Dailly S (2012) Auditing urinary catheter care.

Nursing Standard. 26, 20, 35-40. Date of acceptance: May 6 2011.

Abstract

Urinary catheters are the main cause of hospital-acquired urinary

tract infections among inpatients. Healthcare staff can reduce the

risk of patients developing an infection by ensuring they give

evidence-based care and by removing the catheter as soon as it is

no longer necessary. An audit conducted in a Hampshire hospital

demonstrated there was poor documented evidence that best

practice was being carried out. Therefore a urinary catheter

assessment and monitoring tool was designed to promote best

practice and produce clear evidence that care had been provided.

Author

Sue Dailly

Lead nurse infection prevention and control, Royal Hampshire

County Hospital, Winchester.

Keywords

Audit, infection prevention and control, urinary tract infections

Review

All articles are subject to external double-blind peer review

and checked for plagiarism using automated software.

Online

Guidelines on writing for publication are available at

www.nursing-standard.co.uk. For related articles visit the

archive and search using the keywords above.

NATIONALLY, APPROXIMATELY 20% of all

hospital-acquired infections are urinary tract

infections, with an estimated 80% of these being

linked to urinary catheters (Hospital Infection

Society 2007). The Third Prevalence Study of

Healthcare Associated Infections in Acute

Hospitals in England 2006 found that 31% of

hospital inpatients in England had a urinary

catheter in situ at the time of the survey or within

the previous seven days (Hospital Infection

Society 2007). A hospital-acquired infection

NURSINGSTANDARD / RCNPUBLISHING

means the patient did not have any signs or

symptoms of this infection before admission and

the infection occurred after being in hospital for at

least 48 hours (Weston 2008). It has been estimated

that the risk of bacteriuria in catheterised patients

increases by 3-10% per day every day the catheter

remains in situ (Warren 1997), and 50% of patients

with a catheter in place for ten days will have a

bacteriuria (Saint and Chenoweth 2003). Patients

who develop a hospital-acquired infection can

expect to remain in hospital two and a half times

longer, and incur higher hospital and community

costs, than non-infected patients (Plowman 2000).

Indwelling urinary catheters are associated with

significant mortality and morbidity, and should

be avoided or used for the minimum time possible

(Saint and Chenoweth 2003). The greatest risk

factor for contracting a urinary tract infection is

having a urinary catheter; once inserted, the longer

the duration of catheterisation the greater the

risk of infection (Pellowe et al 2003). Therefore

using alternative urine collection strategies

when appropriate and reducing the duration

of catheterisation are critical in the prevention

of urinary tract infections.

Audit

The Department of Health began mandatory

reporting of meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus

aureus (MRSA) bacteraemias in April 2001. This

quickly demonstrated where serious infections

were occurring nationally and locally (Health

Protection Agency (HPA) 2009). The number

of cases nationally has reduced from 7,247 in

2001/02 (HPA et al 2005) to 1,898 in 2009/10

(HPA 2010). In 2008/09 the Royal Hampshire

County Hospital had five patients with MRSA

bacteraemias. Two were associated with urinary

catheters, of which one was a hospital-acquired

infection and the other a community-acquired

january 18 :: vol 26 no 20 :: 2012 35

p35-40w20_A&S Template 13/01/2012 16:24 Page 36

Art & science infection prevention

infection in a patient admitted from a nursing

home. The remaining three were caused by

wounds or other invasive devices. This focused

hospital staffs attention on urinary catheters as

being an important source of serious infection.

A root cause analysis was carried out on the two

MRSA bacteraemias linked to urinary catheters.

This is a multidisciplinary structured in-depth

investigation to identify how and why each of the

bacteraemias occurred. The patients doctor and

a senior nurse from the ward plus the infection

prevention and control nurses reviewed the notes

and ongoing care form, which revealed poor

quality documentation of the insertion and ongoing

care of both urinary catheters. The staff at the

meeting felt this was a common problem in the

hospital and a hospital-wide audit was carried out

to examine the quality of urinary catheter care.

Audits are used by infection prevention and

control teams to show that staff are carrying

out best practice, for example in urinary

catheterisation, and that procedures are being

followed correctly. Audit is a requirement of the

Health Act 2006: Code of Practice, which states

that NHS organisations must audit key policies

and procedures for infection prevention.

Designing an effective audit tool can be challenging

for staff. However, there are a large number of

audits already prepared that staff can use or adapt

to match local policy. Audit tools such as Saving

Lives (Department of Health 2007) now replaced

by the High Impact Interventions (Department of

Health 2011) and those published by the Infection

Prevention Society provide useful guidance.

The Royal Hampshire County Hospitals policy

is based on national evidence-based guidelines

(Pratt et al 2007). It therefore seemed appropriate

to use the Saving Lives care bundle on urinary

catheter care as the basis for the audit tool because

this reflects the epic2 guidelines. The Saving Lives

care bundle approach to urinary catheter insertion

and ongoing care lists the essential components or

steps required to insert and carry out ongoing

urinary catheter care. The risk of infection reduces

if all the elements of the care bundle are performed

for every patient every time. If one or more elements

of the care bundle is excluded or not undertaken,

then the patients risk of infection increases.

The aim is to observe practice, evaluate the

implementation of key elements of care, provide

feedback on the results and develop ideas for

improvement (Department of Health 2011).

Method

In June 2009 a hospital-wide urinary catheter

audit was undertaken which was divided into

four sections:

36 january 18 :: vol 26 no 20 :: 2012

4Observation of the insertion of urinary

catheters.

4Observation of emptying a urinary catheter bag.

4Prevalence study of patients with urinary

catheters and an audit of the documentation

of catheter insertion and ongoing care.

4Questions for staff to assess their knowledge

of urinary catheters and catheter-associated

urinary tract infections.

The infection prevention and control nurses

asked all healthcare staff to observe each others

practice and to record how someone inserts

a urinary catheter, rather than completing

a self-assessment form. This is because the

downside to self-assessment forms is that

staff may not be aware they are carrying

out care incorrectly or may not feel able to admit

this because they are embarrassed or fear the

consequences (Harvey 2002). Observed audit

provides proof that staff are compliant with

hospital standards and policies, although

consideration should be given to the Hawthorne

effect,where a member of staffs behaviour

changes because they are being observed

(Watson et al 2008).

Staff also carried out observations of ongoing

catheter care; this is often done by healthcare

assistants, while urinary catheter insertion tends

to be carried out by qualified nursing or medical

staff. Many different groups and grades of staff

took part in the audit.

A prevalence study involving a spot check was

used to identify how many patients had a catheter

in situ on a specific day, the reason for catheter

insertion and the quality of the documentation.

The three infection prevention and control nurses

divided the hospital between them and visited each

ward on one specific day.

A quiz was devised to ascertain from staff

what facts they knew about catheters and

urinary tract infections. Offering a prize draw

was helpful in motivating staff to do the quiz

rather than asking them to complete a

questionnaire as part of the audit.

Results

Four hundred patients on 22 wards took part in

the audit in June 2009. Nineteen per cent (n=76)

of the hospitals inpatients had a urinary catheter

in situ.

Urinary catheter insertion care bundle

For the audit of urinary catheter insertion, 85%

(n=65) of patients had all the key elements of the

care bundle performed (Figure 1). No catheter

insertions were observed on the labour or

maternity wards, only in surgery and medicine.

NURSINGSTANDARD / RCNPUBLISHING

p35-40w20_A&S Template 13/01/2012 16:24 Page 37

Staff knowledge quiz

Staff were well informed about urinary catheter

insertions and ongoing care, but reported that

they had not received any formal training

for several years. Although catheter care is

mentioned in an infection control annual update,

many staff requested a more formal training

session. Local ward-based sessions were

commenced for staff to attend.

FIGURE 1

Results for urinary catheter insertion (n=76)

100

80

60

40

Medicine

NURSINGSTANDARD / RCNPUBLISHING

Results for ongoing catheter care (n=76)

100

80

60

40

Medicine

Surgery

Handwashing

technique

Catheter still

required

Bag position

Patient

hygiene

Hand hygiene

after care

Apron

Gloves

20

Hand hygiene

before care

Percentage (%)

Family services

FIGURE 3

Results for documentation (n=76)

100

80

Medicine

Surgery

Job title

Name

Type

Length

Size

Time

40

20

0

Date

60

Reason

Documentation

The reason for catheter insertion was recorded

on average for 80% (n=61) of patients, but

documentation was often incomplete (Figure 3).

Usually the catheter packet sticker could be

located in the medical notes providing the date

of insertion. Sometimes the reason for insertion

was recorded with an illegible name and a bleep

number. Occasionally the word catheterise

was in a list of tasks to be completed with a tick

next to it.

The documentation for ongoing care was often

poor. The medical notes may mention catheter

still draining as part of the daily ward round.

Nursing notes were often no better; catheter

draining well may be the only reference to

show the patient still has a catheter in place.

The medical and nursing documentation was not

detailed enough to show whether or not the

Saving Lives care bundle had been complied

with. There was usually no mention of catheter

hygiene being carried out, whether the bag was

positioned off the floor or had been changed.

Surgery

FIGURE 2

Percentage (%)

Ongoing catheter care

For the audit of ongoing catheter care, 58%

(n=44) of patients received all aspects of care

outlined in the care bundle (Figure 2). The main

areas of non-compliance were:

4Not wearing an apron.

4No documentation that daily meatal hygiene

was being carried out.

Personal

protective

clothing

Hand

hygiene

Closed

system

Meatal

cleansing

Aseptic

technique

20

Lubricant

used

Percentage (%)

Areas of poor compliance with the standards

outlined in the care bundle were:

4Not wearing an apron because some staff

did not anticipate their uniform being

contaminated.

4Using chlorhexidine and cetrimide solution

instead of sodium chloride for meatal cleaning.

4Not always using a lubricant when

catheterising a female patient.

4Breaking the catheters closed system

prematurely. When a catheter is inserted and

the first bag is attached, a closed system is

formed. Each time the bag is changed it breaks

the closed system the more frequently this

occurs, the greater the risk of introducing

bacteria. The urinary catheter comes without

a bag attached, so staff have to decide which

type of bag is most appropriate for that

patients requirements. Most catheter bag

manufacturers recommend changing the bag

every five to seven days, so staff need to consider

whether the patient will be mobile in the next

few days and if so whether a leg bag be

attached. An hourly monitoring bag should be

used if accurate urine measurement is crucial.

Family services

january 18 :: vol 26 no 20 :: 2012 37

p35-40w20_A&S Template 13/01/2012 16:24 Page 38

Art & science infection prevention

Summary of audit results

The 2009 urinary catheter audit showed:

4Poor compliance with the use of aprons.

4Poor compliance with documentation

on catheter insertion and ongoing care.

4Delayed removal of catheters and confusion

over responsibility for their removal.

Dissemination of results

Prompt feedback of results and action planning

in teams is a crucial part of the audit cycle and

promotes local ownership to support effective

changes (Chambers and Wakley 2005). The

infection prevention and control nurses

disseminated the results to the weekly nursing

quality indicator meeting so that ward-based

staff were aware and had an opportunity to

discuss what they could do in their clinical areas

to make improvements. The results were

discussed at divisional meetings and the infection

prevention and control committee. One infection

prevention and control nurse also attended the

medical staffs meeting to present the results. The

interactive discussion between the consultants

enabled stroke physicians to explain why leaving

urinary catheters in place longer than necessary

caused long-term problems for patients.

Interestingly, few of the doctors present, apart

from those working in the care of older people,

reviewed whether urinary catheters should be

removed on their ward rounds; however, they did

review whether central venous catheters should

be removed. There seemed to be an assumption

that nurses would make the decision when to

remove a urinary catheter, and yet it had often

been inserted for medical reasons. The meeting

highlighted to a large group of doctors that the

removal of a urinary catheter needs to be

reviewed on every ward round.

The infection prevention and control nurse

monthly newsletter provided a summary of the

audit and recommendations for improvements

in practice. This newsletter goes out to all hospital

employees and is a useful way to share important

information with staff.

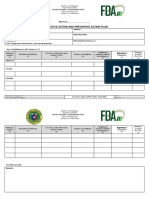

Action plan

The infection prevention and control nurses

began ward-based education sessions to

highlight the results of the audit and discuss

with staff how improvements could be made.

The main issue was how to tackle the problem

of poor documentation. If staff are not aware of

the reason why the catheter was inserted, how

can they decide when to remove it? The hospital

staff had been using a Visual Infusion Phlebitis

38 january 18 :: vol 26 no 20 :: 2012

(VIP) score form, which is based on Jacksons

(1998) work on intravenous cannula care.

The introduction of the form had improved

compliance with documentation on the insertion

and ongoing care of intravenous cannulae

significantly, but more importantly it had also

promoted prompt intravenous cannula removal.

The infection prevention and control nurses

therefore designed a urinary catheter assessment

and monitoring (UCAM) form for urinary

catheter insertion and ongoing care based on the

VIP score form. It included the Saving Lives care

bundle for insertion and ongoing care. It was A4

in size, had space for the identification sticker

from the packet the catheter comes in and

included the question for each day is the catheter

still required?. It was piloted on several wards to

get feedback from staff who would be using the

new form.

Feedback from the pilot was mixed and

included positive and negative comments, such as

seems like a good idea and not another piece of

paper, but the most common response we had

was that it was similar to the VIP form. This is

probably because VIP score charts had been used

successfully for some time, so having a similar form

for urinary catheters seemed acceptable to staff.

As a result of the pilot, some of the wording

and layout of the UCAM form was changed to

incorporate staff feedback. By September 2009

the UCAM form was introduced on the wards.

The forms were pre-printed in pads of 50 at

a cost of 2.38 per pad.

Follow-up audits

Having introduced the new form, it was

important to assess whether the quality of the

documentation on insertion and ongoing care of

urinary catheters had improved and whether the

UCAM form was promoting prompt catheter

removal. The infection prevention and control

nurses carried out two spot checks, one in

December 2009 and one in January 2010.

In December 2009, 21% of patients in the

hospital (66 out of 311 patients) had catheters

in place, and 23% (70 out of 303 patients) had

catheters in January 2010.

While carrying out the spot checks it became

apparent that there was a significant difference

in the number of patients who had catheters

inserted depending on which day of the week the

prevalence study was carried out. On Monday

there were no gynaecology patients with

catheters and few surgical and orthopaedic

patients. By Wednesday, more patients had

catheters inserted as a requirement of their

surgical procedure. However, counting the

NURSINGSTANDARD / RCNPUBLISHING

p35-40w20_A&S Template 13/01/2012 16:24 Page 39

number of catheters in situ was not going

to demonstrate an improvement in the quality

of patient care. The audit of UCAM

effectiveness needed to focus on aspects such as

documentation of the reason for urinary catheter

insertion, with evidence that a bladder scan had

been carried out before catheter insertion. Daily

recording on an UCAM form that the patient had

received meatal hygiene and that the catheter bag

had been checked and was positioned off the

floor demonstrated compliance with the care

bundle. The infection prevention and control

nurses were specifically interested in observing

whether the catheter was removed on the same

day if the answer to the question on the form is

the catheter still required? was no.

Although 99% (n=69) of patients with a

urinary catheter had a UCAM form by January

2010, the documented information was often

incomplete. This was because staff appeared to

focus on completing the parts of the form they

thought were important rather than all of the

sections, as described below:

4Theatre and recovery staff were good at

documenting catheter insertion details and

ensured that no patient left recovery without

one of the forms being completed, even if the

person inserting the catheter did not complete

the paperwork. What mattered was that the

patient had the form, with the details of the

catheterisation and the name of the person

who inserted it.

4Staff in the emergency department were not

as good at using the forms and tended to

document catheter insertion in the emergency

department notes.

4On the surgical wards the UCAM form was

sometimes left at the back of the patients folder

with the surgical records, rather than being

moved to the front of the folder with the

observation chart and the VIP score form.

4Staff on several wards reviewed their UCAM

and VIP score forms when the daily observations

were carried out at 2pm to ensure the forms were

complete for the morning ward rounds.

4The most common and significant response was

that staff reported that the form prompted them

to ask each day is the catheter still required?.

Several healthcare assistants commented that the

form made them feel empowered to ask a nurse

or doctor if a patients catheter was still required.

From April 2010 compliance with the UCAM

form became one of the weekly audits carried

out on each ward. Five patients per ward with

a urinary catheter (this number could be lower

if fewer patients had catheters in place)

had their UCAM documentation audited. The

results are entered on an Excel spreadsheet so that

NURSINGSTANDARD / RCNPUBLISHING

staff on each ward could compare scores with

those of other wards. Staff from each ward

present their results at the hospitals weekly

quality indicator meeting. This provides an

opportunity for staff to discuss what changes

could take place on the wards and to inform staff

in the emergency department when the UCAM

form has not been completed before the patient

leaves the department.

In June 2010 it was decided to repeat the audit

over several weeks, but this time the focus was

on the use of the UCAM form. Of the 80 patients

audited, 90% (n=72) had a UCAM form;

67% (n=54) had the insertion details completed

those that were not complete did have the health

professionals name, date and reason for insertion

completed; 65% (n=52) had ongoing care details

completed; others had either missed a day or had

not signed a column on the form. The main reason

for poor compliance with ongoing care was that

the form was not at the end of the patients bed

with the observation chart and VIP form, but was

lost among the admission assessments or theatre

paperwork. Further work is therefore required

to ensure better compliance in completing the

UCAM form.

Outcomes

The audit showed significant improvement in the

quality of the documentation for insertion and

ongoing care following the introduction of the

UCAM form. Most of the essential information,

such as the reason for insertion, was recorded on

the form, which was easily located at the end of

the patients bed. Ongoing care was documented

providing clear evidence of meatal hygiene and

catheter bag changes. Staff reported that they are

prompted to remove the catheter and more junior

staff stated that they feel empowered to ask

medical staff if the catheter is still required.

Consequently, the weekly quality audits show

that on average 194 catheters per month are

audited with only one or two per month deemed

unnecessary, which are removed following the

audit. The use of catheters for some surgical

procedures is now being challenged and

intermittent catheterisation is being used for

enhanced recovery orthopaedic procedures. No

MRSA bacteraemias have been linked to urinary

catheters since September 2009.

The UCAM form was included as one of the high

impact actions for nursing and midwifery in The

Essential Collection (NHS Institute for Innovation

and Improvement 2010). This is a collection of

innovations and changes introduced by nurses that

have made improvements to the quality of patient

care. The infection prevention and control nurses

january 18 :: vol 26 no 20 :: 2012 39

p35-40w20_A&S Template 13/01/2012 16:24 Page 40

Art & science infection prevention

and staff from the hospital were interviewed as

part of the project. Copies of the UCAM form

can be found on the NHS Institute for

Innovation and Improvement website

(http://tiny.cc/UCAM_form).

The infection prevention and control nurses

found that the UCAM form not only improved

documentation but also prompted timely removal

of urinary catheters. As the greatest risk for

acquiring a urinary tract infection is having a

catheter and, once inserted, the greatest risk

factor is the duration of catheterisation, the

prompt removal of a catheter will reduce a

patients risk of developing a catheter-associated

urinary tract infection as well as the associated

personal and financial effects that this type of

infection can have.

demonstrated this was a hospital-wide problem.

A UCAM form was developed that has provided

staff with a single form on which all information

linked to urinary catheter insertion and ongoing

care can be recorded. It also prompts staff to

adhere to best practice and, more importantly,

provides documented evidence that the care

has been carried out. Weekly audits on

compliance with the UCAM form and

documentation of whether the catheter is still

required provide ongoing evidence that the

hospital has improved the quality of patient

care relating to urinary catheters NS

USEFULRESOURCES

4Health Protection Agency

www.hpa.org.uk

Conclusion

4Infection Prevention Society

Examination of two MRSA bacteraemias at the

Royal Hampshire County Hospital revealed poor

documentation of insertion and care of urinary

catheters. An audit was carried out that

www.ips.uk.net

4NHS Institute for Innovations and Improvement

www.institute.nhs.uk

References

Chambers R, Wakley G (2005)

Clinical Audit in Primary Care:

Demonstrating Quality and Outcomes.

Radcliffe Publishing, Milton Keynes.

Department of Health (2007)

Saving Lives: Reducing Infection,

Delivering Clean and Safe Care.

The Stationery Office, London.

Department of Health (2011) High

Impact Interventions. http://hcai.dh.

gov.uk/whatdoido/high-impactinterventions (Last accessed:

December 19 2011.)

Harvey L (2002) Evaluation

for what? Teaching in Higher

Education. 7, 3, 245-263.

Health Protection Agency (2009)

Results of the First Three and a

Half Years of the Department

of Healths Mandatory Methicillin

Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus

(MRSA) Surveillance System

in Acute Trusts in England.

http://tiny.cc/HPA_MRSA (Last

accessed: December 19 2011.)

Health Protection Agency (2010)

Healthcare-Associated Infections

and Antimicrobial Resistance:

2009/10. http://bit.ly/tRuB2G

(Last accessed: December 19 2011.)

Health Protection Agency,

Communicable Disease Surveillance

Centre, Department of Health

(2005) MRSA Surveillance System:

Results. http://tiny.cc/DH_4085951

(Last accessed: December 19 2011.)

Hospital Infection Society (2007)

The Third Prevalence Survey of

Healthcare Associated Infections

in Acute Hospitals in England 2006.

The Stationery Office, London.

Jackson A (1998) Infection control

a battle in vein: infusion phlebitis.

Nursing Times. 94, 4, 68-71.

40 january 18 :: vol 26 no 20 :: 2012

NHS Institute for Innovation

and Improvement (2010) High

Impact Actions for Nursing

and Midwifery: The Essential

Collection. NHS Institute for

Innovation and Improvement,

Coventry.

Pellowe CM, Pratt RJ, Harper HP

et al (2003) Prevention of

healthcare-associated infections

in primary and community care.

Journal of Hospital Infection.

55, Suppl 2, S5-S127.

Plowman R (2000) The

socioeconomic burden of hospital

acquired infection. Eurosurveillance.

5, 4, 49-50.

Pratt RJ, Pellowe CM,

Wilson JA et al (2007) epic2:

National evidence-based guidelines

for preventing healthcareassociated infections in NHS

hospitals in England. Journal of

Hospital Infection. 65, Suppl 1,

S1-S64.

Saint S, Chenoweth CE (2003)

Biofilms and catheter-associated

urinary tract infections. Infectious

Disease Clinics of North America.

17, 2, 411-432.

Warren JW (1997)

Catheter-associated urinary tract

infections. Infectious Diseases

Clinics of North America. 11, 3,

609-622.

Watson R, McKenna H, Cowman S,

Keady J (2008) Nursing Research:

Designs and Methods.

Churchill Livingstone Elsevier,

Philadelphia PA.

Weston D (2008) Infection

Prevention and Control: Theory

and Practice for Healthcare

Professionals. John Wiley & Sons,

Chichester.

NURSINGSTANDARD / RCNPUBLISHING

Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

You might also like

- Nurse-Directed Interventions To Reduce Catheter-Associated Urinary Tract InfectionsDocument10 pagesNurse-Directed Interventions To Reduce Catheter-Associated Urinary Tract InfectionsAngernani Trias WulandariNo ratings yet

- Implementing An Evidence-Based Practice Protocol For Prevention of Catheterized Associated Urinary Tract Infections in A Progressive Care UnitDocument9 pagesImplementing An Evidence-Based Practice Protocol For Prevention of Catheterized Associated Urinary Tract Infections in A Progressive Care UnitLina Mahayaty SembiringNo ratings yet

- Ebp Cauti Research PaperDocument11 pagesEbp Cauti Research Paperapi-598708595No ratings yet

- Cauti101 508Document40 pagesCauti101 508Yahia HassaanNo ratings yet

- Articulo en InglesDocument8 pagesArticulo en Inglesdante yonathan villegas lozanoNo ratings yet

- Cauti PreventionDocument25 pagesCauti Preventionapi-340511634No ratings yet

- Ebp UtiDocument7 pagesEbp Utiapi-234511817No ratings yet

- Abubakar Et Al Sistematic ReviewDocument35 pagesAbubakar Et Al Sistematic ReviewIrfan MadamangNo ratings yet

- Cauti Prevention - UpdatedDocument25 pagesCauti Prevention - Updatedapi-340518242No ratings yet

- Final Cauti Leadership Analysis Paper Nurs440Document9 pagesFinal Cauti Leadership Analysis Paper Nurs440api-251662522No ratings yet

- Nurs 363 Ebp Group Project Final Paper 1Document11 pagesNurs 363 Ebp Group Project Final Paper 1api-269170045No ratings yet

- Zurmehly 2018Document6 pagesZurmehly 2018DavennBacudNo ratings yet

- Qsen Project Urinary Catheter ComplicationsDocument18 pagesQsen Project Urinary Catheter Complicationsapi-316643564No ratings yet

- Catheter-Associated Urinary Tract InfectionsDocument20 pagesCatheter-Associated Urinary Tract Infectionsapi-315336673No ratings yet

- Article 1Document8 pagesArticle 1Sherlaz EfhalNo ratings yet

- Barriers To Urinary Catheter Insertion and Management PracticesDocument5 pagesBarriers To Urinary Catheter Insertion and Management PracticesHelmy HanafiNo ratings yet

- Nurs490 Cauti Safety Paper NeuburgDocument17 pagesNurs490 Cauti Safety Paper Neuburgapi-452041818100% (1)

- Nurse Driven Protocols ArticleDocument7 pagesNurse Driven Protocols ArticlePaolo VegaNo ratings yet

- PDFDocument9 pagesPDFEven Un Holic100% (1)

- Ebp Picc Line - RevisedDocument6 pagesEbp Picc Line - Revisedapi-234544335No ratings yet

- Urinary CatheterDocument22 pagesUrinary Catheterايمان عمرانNo ratings yet

- Essay NursingDocument5 pagesEssay Nursingapi-520141947No ratings yet

- Studyoninfectioncontrol CHENNAIDocument8 pagesStudyoninfectioncontrol CHENNAIDickson DanielrajNo ratings yet

- Control of Hospital Acquired Infections in The ICU: A Service PerspectiveDocument5 pagesControl of Hospital Acquired Infections in The ICU: A Service PerspectiveAndriyanto HermawanNo ratings yet

- Cauti Qi PosterDocument1 pageCauti Qi Posterapi-219780992No ratings yet

- Study On Infection ControlDocument8 pagesStudy On Infection ControllulukzNo ratings yet

- A Nurse-Driven Process For TimelyDocument7 pagesA Nurse-Driven Process For TimelyWardah Fauziah El SofwanNo ratings yet

- Contributing Factors in Increasing Health Care Associated Infection (Hai's) in Phlebitis CasesDocument8 pagesContributing Factors in Increasing Health Care Associated Infection (Hai's) in Phlebitis CasesJenny MaulidyaNo ratings yet

- Final Quality Improvement PaperDocument8 pagesFinal Quality Improvement Paperapi-251822043No ratings yet

- Get Homework/Assignment DoneDocument6 pagesGet Homework/Assignment Donehomeworkping1No ratings yet

- 13-2 Collated 3 (3) - 149-155Document7 pages13-2 Collated 3 (3) - 149-155Inas AzharNo ratings yet

- Journal For MEdical WardDocument8 pagesJournal For MEdical WardValcrist BalderNo ratings yet

- Effect of Educational Program On Nurses' Practice Regarding Care of Adult Patients With Endotracheal TubeDocument28 pagesEffect of Educational Program On Nurses' Practice Regarding Care of Adult Patients With Endotracheal TubeadultnursingspecialtyNo ratings yet

- Rba 0 AheadOfPrint 6036c54fa95395582f07f644Document5 pagesRba 0 AheadOfPrint 6036c54fa95395582f07f644STRMoch Hafizh AlfiansyahNo ratings yet

- Failure of Sterilization in A Dental Outpatient FaDocument7 pagesFailure of Sterilization in A Dental Outpatient FaNara PangestuNo ratings yet

- Video 4 PDFDocument9 pagesVideo 4 PDFMirza RisqaNo ratings yet

- Ebp FormativeDocument12 pagesEbp Formativeapi-288858560No ratings yet

- Shaffer2017-Tutku MacBook ProDocument6 pagesShaffer2017-Tutku MacBook ProMEKSELINA KALENDERNo ratings yet

- Artículo BiochemDocument16 pagesArtículo BiochemViankis García100% (1)

- DocxDocument5 pagesDocxkamau samuelNo ratings yet

- انترودكشن عمليDocument13 pagesانترودكشن عمليRana KhaledNo ratings yet

- Qi Group Project - e C y TDocument10 pagesQi Group Project - e C y Tapi-302732994No ratings yet

- Urine Specimen Collection - How A Multidisciplinary Team Improved Patient Outcomes Using Best Practices - ProQuestDocument9 pagesUrine Specimen Collection - How A Multidisciplinary Team Improved Patient Outcomes Using Best Practices - ProQuestHelmy HanafiNo ratings yet

- 240 Epb PaperDocument8 pages240 Epb Paperapi-204875536No ratings yet

- Qi Project FinalDocument6 pagesQi Project Finalapi-642984838No ratings yet

- Synopsis LatestDocument23 pagesSynopsis LatestPreeti ChouhanNo ratings yet

- Intervention To Reduce Catheter-Related Bloodstream Infections in An Intensive Care Unit at A Regional Hospital in Southern TaiwanDocument2 pagesIntervention To Reduce Catheter-Related Bloodstream Infections in An Intensive Care Unit at A Regional Hospital in Southern TaiwanTessa Elviana SeptiNo ratings yet

- Analisis Jurnal: Disusun Dalam Rangka Memenuhi Tugas Stase Keperawatan DasarDocument6 pagesAnalisis Jurnal: Disusun Dalam Rangka Memenuhi Tugas Stase Keperawatan DasarNur FitriNo ratings yet

- Catheter Associated Urinary Tract Infection Literature ReviewDocument8 pagesCatheter Associated Urinary Tract Infection Literature Reviewea1yd6vnNo ratings yet

- Runa Debbarma Urinary Tract InfectionDocument18 pagesRuna Debbarma Urinary Tract InfectionMs Runa DebbarmaNo ratings yet

- Knowledge and Practice of Nursing Staff Towards InfectionDocument13 pagesKnowledge and Practice of Nursing Staff Towards InfectionZein AhmadNo ratings yet

- PSMID 2017 Guidelines For HIV Infected HCWsDocument17 pagesPSMID 2017 Guidelines For HIV Infected HCWsithran khoNo ratings yet

- 34 Original - Effectiveness of Betadine Vs Normal Saline in Catheter Care For Prevention of Catheter Associated Urinary TractDocument4 pages34 Original - Effectiveness of Betadine Vs Normal Saline in Catheter Care For Prevention of Catheter Associated Urinary TractM EhabNo ratings yet

- Benchmark Capstone Project Change Proposal Week 8Document15 pagesBenchmark Capstone Project Change Proposal Week 8Kerry-Ann Brissett-SmellieNo ratings yet

- Cathere Care PDFDocument1 pageCathere Care PDFNinan ChackoNo ratings yet

- Making Health Care Safer.2Document9 pagesMaking Health Care Safer.2YANNo ratings yet

- Microbiology for Surgical Infections: Diagnosis, Prognosis and TreatmentFrom EverandMicrobiology for Surgical Infections: Diagnosis, Prognosis and TreatmentKateryna KonNo ratings yet

- Endoscopic Diagnosis and Treatment in Urinary Bladder Pathology: Handbook of EndourologyFrom EverandEndoscopic Diagnosis and Treatment in Urinary Bladder Pathology: Handbook of EndourologyPetrisor Aurelian GeavleteRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Stacey Martino - How One Person Can Transform Any Relationship and Save A MarriageDocument22 pagesStacey Martino - How One Person Can Transform Any Relationship and Save A Marriagegabyk68No ratings yet

- Megaloblastic Anemia Clinical Presentation - History, Physical ExaminationDocument5 pagesMegaloblastic Anemia Clinical Presentation - History, Physical ExaminationAsyifa HildaNo ratings yet

- Framework Trend and Scope of Nursing PracticeDocument28 pagesFramework Trend and Scope of Nursing PracticeShaells Joshi80% (5)

- Assesment of Knowledge of Analgesic Drugs in Pregnant WomenDocument6 pagesAssesment of Knowledge of Analgesic Drugs in Pregnant WomenMahrukh AmeerNo ratings yet

- New Microsoft Office Word DocumentDocument3 pagesNew Microsoft Office Word DocumentAtulsanapNo ratings yet

- AAPMR - What Makes The Practice of Physiatry MultidisciplinaryDocument3 pagesAAPMR - What Makes The Practice of Physiatry MultidisciplinaryJared CoganNo ratings yet

- NIS Study Guide 2020Document48 pagesNIS Study Guide 2020TM GPONo ratings yet

- Javamagazine20111112 DLDocument58 pagesJavamagazine20111112 DLGeorgios MantzouranisNo ratings yet

- ReflectionDocument9 pagesReflectionVino VinnoliNo ratings yet

- The Omaha System As A Structured Instrument For Bridging Nursing Informatics With Public Health Nursing EducationDocument9 pagesThe Omaha System As A Structured Instrument For Bridging Nursing Informatics With Public Health Nursing EducationAwkaren100% (1)

- MRC - Sudan - Company Profile 2022Document6 pagesMRC - Sudan - Company Profile 2022Mohamed Mohamed Abdelrhman FadlNo ratings yet

- Nursing 494Document18 pagesNursing 494Aaroma BaghNo ratings yet

- Irrational Use of DrugDocument9 pagesIrrational Use of Drugsreedam100% (2)

- Our MissionDocument5 pagesOur MissionShohaib Khan TanoliNo ratings yet

- iTECH PROJECT - JOB OPPORTUNITIESDocument6 pagesiTECH PROJECT - JOB OPPORTUNITIESKevinNo ratings yet

- Health Assesment LectureDocument15 pagesHealth Assesment LecturemeowzartNo ratings yet

- Pharmacy ListDocument115 pagesPharmacy ListacroxmassNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Fixxxx 1Document14 pagesJurnal Fixxxx 1heryanggunNo ratings yet

- Conducting Randomised Controlled Trials Across Countries With Disparate Levels of Socio-Economic Development: The Experience of The Asia-Pacific Hepatocellular Carcinoma Trials GroupDocument6 pagesConducting Randomised Controlled Trials Across Countries With Disparate Levels of Socio-Economic Development: The Experience of The Asia-Pacific Hepatocellular Carcinoma Trials GroupPierce ChowNo ratings yet

- Lidocaine Lozenges For Pharyngeal Anesthesia DurinDocument6 pagesLidocaine Lozenges For Pharyngeal Anesthesia DurinpaulaNo ratings yet

- October 2019 PDFDocument71 pagesOctober 2019 PDFFehr GrahamNo ratings yet

- Capa Plan 2018Document3 pagesCapa Plan 2018Cha Gabriel100% (2)

- Educational Preparation: Mrs. Debajani SahooDocument46 pagesEducational Preparation: Mrs. Debajani Sahookumar alokNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 103.229.203.198 On Wed, 13 Apr 2022 07:01:02 UTCDocument7 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 103.229.203.198 On Wed, 13 Apr 2022 07:01:02 UTCDewi Utami IrianiNo ratings yet

- Current Concepts Profilaxis CMFDocument11 pagesCurrent Concepts Profilaxis CMFEliseo ValdezNo ratings yet

- Ctu Kab CianjurDocument29 pagesCtu Kab CianjurDEDE PURINo ratings yet

- Job Advert - Clinical Psychologist080823Document2 pagesJob Advert - Clinical Psychologist080823tutorfelix777No ratings yet

- Spending Habits Paper Group of 5Document13 pagesSpending Habits Paper Group of 5Adrian AvalosNo ratings yet

- MAPEH 6 - Demo COTDocument36 pagesMAPEH 6 - Demo COTLucena GhieNo ratings yet

- PHA6118 Course Orientation Portfolio 2TAY2022-23 Salonga ForRevision v3Document25 pagesPHA6118 Course Orientation Portfolio 2TAY2022-23 Salonga ForRevision v3christian redotaNo ratings yet