Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Doctors of Tomorrow - A Pipeline Program For Getting A Head Start in Medicine

Uploaded by

theijesOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Doctors of Tomorrow - A Pipeline Program For Getting A Head Start in Medicine

Uploaded by

theijesCopyright:

Available Formats

International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Invention

ISSN (Online): 2319 7722, ISSN (Print): 2319 7714

www.ijhssi.org ||Volume 5 Issue 9||September. 2016 || PP.33-37

Doctors of Tomorrow A Pipeline Program for Getting a Head

Start in Medicine

Paula T. Ross PhD1, Elizabeth Yates2, Jordan Derck3, Jonathan F. Finks MD4,

Gurjit Sandhu PhD5

1

Paula T. Ross is Director of Advancing Scholarship at the University of Michigan Medical School, Ann Arbor,

MI

2

Elizabeth Yates is a fourth-year medical student and a former Director of Continuing Involvement for the

Doctors of Tomorrow Program, University of Michigan Medical School, Ann Arbor, MI

3

Jordan Derck is a fourth-year medical student and a former Director of Programing for the Doctors of

Tomorrow Program, University of Michigan Medical School, Ann Arbor, MI

4

Jonathan F. Finks is Associate Professor of Surgery and Director of the Doctors of Tomorrow Program,

University of Michigan Medical School, Ann Arbor MI

5

Gurjit Sandhu, is Assistant Professor, Departments of Surgery and Learning Health Sciences, University of

Michigan Medical School, Ann Arbor, MI

ABSTRACT

Purpose: Pipeline programs have long been embraced as a strategyto recruit students from groups

underrepresented in medicine into medical careers. Despite the prevalence of these programs, we know little

about why students seek out participation and even less about their perceptions of the potential long-term

benefits. This study explored the motivations and expectations of pipeline program participants.

Method: Twenty-three high school students participated in the Doctors of Tomorrow (DoT) program, a high

school and medical school partnership pipeline program from September 2014 through March 2015. Data for

this study included students application essays, critical incident narratives, focus group discussions and

transcripts from individual interviews. Thematic analysis was used to analyze all narrative materials and

transcripts.

Results: Our analysis of all program data revealed that DoT participants were motivated to participate in the

program to learn about becoming a physician, gain access to individuals in medicine and develop a competitive

advantage over other students when applying to college and medical school.

Conclusions: Barriers to careers in medicine for individuals from groups underrepresented in medicine is well

documented. These findings suggest that students seek to participate in pipeline programs as astrategy to

secure goal-oriented, experiential encounters to help improve access points and mitigate barriers to becoming

physicians.

Keywords: minority student, pipeline, K-12, diversity in medicine, underrepresentation in medicine

[The DoT is] a combination of opportunities. Its exposure, [its] everything. You get to see what your life

would be if you were there. (9th grade high school student)

I. INTRODUCTION

Medicine and medical education in the United States are in the midst of marked transformation,

including overhauling curricula and assessment methods, increasing demands for accountability and

transparency to the public, and decreasing research dollars. 1,2 What has not changed is the lack of racial

diversity in medicine.3Due to inequitable educational preparation in elementary and secondary settings, financial

demands, and unfamiliar socio-cultural contexts of medical schools, access to elite health professions has been

exclusionary for members of many communities and continues to fuel their underrepresentation in medicine

(URiM).3,4The term underrepresentation in medicinehas been used by the American Association of Medical

Colleges (AAMC) since the early 1970s to define minority groups excluded from participation in the medicine

profession.4The American Association of Medical Colleges (AAMC) and the National Medical Association

(NMA) continue to call for initiatives to address disparities and underrepresentation among physicians. 5,6

Nonetheless, entry into the profession of medicine remains elusive for youth from certain minority groups.

Pipeline programs that focus on the transition from undergraduate education to medical school have

been used as a strategy to increase diversity in medicine and address inequities associated with recruitment,

access, and retention of studentsfrom groups underrepresented in medical school. 7-9 Despite the prevalence of

pipeline programs across the UnitedStates, minority youth remain under-represented in medical school,10

perhaps because the pipeline needs to begin earlier in their academic trajectory.In 2015, the AAMC

www.ijhssi.org

33 | Page

Doctors of Tomorrow A Pipeline Program for Getting a Head Start in Medicine

Matriculating Student Questionnaire conducted with incoming U.S. medical students, found that 19.9% of

respondents realized they wanted to become a doctor before high school and 30.5% realized during high

school.11Their finding that over half of medical students chose to pursue a career in medicine by the end of high

school highlights the need for earlier engagementof students interested in careers in medicine. 12

Focusing on high school students is an important strategy for increasing the pool of qualified minority

medical schoolapplicants13, yet little is known about why students seek out these programs and their perceptions

of the long-term benefits. We sought to better understand the perspectives of underrepresented high school

youth in their pursuit of careers in medicine. We were interested in exploring their motivations for participating

in a medical career pipeline program and what the students perceived to be the primary benefits of participation

in order to build on those defined areas of need.

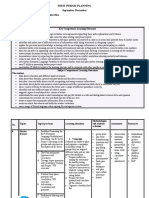

II. METHODS

Setting

The Doctors of Tomorrow (DoT) program is a partnership between the University of Michigan Medical

School and Cass Technical High School (CTHS), the oldest of only three magnet schools in Detroit. CTHS

admits students largely based on middle school grades and high school placement test scores, and students must

maintain a GPA of at least 2.5 to remain enrolled. The 2300 members of the student body are reflective of the

greater Detroit population with 90% of students identifying as African American or Hispanic. 14,15 The

23students included in this study were 9th graders at CTHS who were selected to participate in the DoT program

during the 2014-2015 academic year. Three students were Asian American and 20 students were African

American.Students were chosen based solely upon their written responses to application questions about their

interest in medicine. Approximately half of the CTHS students who applied were accepted.

The overarching goalof DoT is to inspire and empower (URiM)students to pursue careers in medicine

and thereby improve the diversity of the physician population. The DoT pipeline model is predicated on

capturing interest and enabling high school students to pursue careers in medicine. The core components of the

program are threefold. First, 9th grade students make monthly visits to the hospital campus for hands on clinical

experiencesincluding physician shadowing opportunities and laparoscopic surgery skills teaching in a simulation

center. Second, one-on-one mentoring from a medical student provides each participant with a near-peer mentor

who can share their knowledge and experience and discuss academic issues, college applications, volunteering

opportunities, and requirements for college preparation. Finally, students complete collaborative end-of-year

capstone service projects related to locally relevant health issues.

Data Collection

The data for this study included application essays, focus groups transcripts, semi-structured interview

transcripts, and critical incident narratives.Data was collected from September 2014 to March 2015. Three

members of the research team (LY, JD, GS) facilitated focus groups and face-to-face interviews. Focus groups

were approximately 25 minutes in duration, and each interview lasted about 15 minutes. To elicit their

motivations for participation, students were asked why they joined DoT, what they hoped to gain from

participation in the program, what suggestions they had for improving the program, and ways to further support

students. Each student wrote a critical incident narrative16,17reflecting on significant or transformative

experiences while participating in DoT. The application essay asked students to explain their interest in the

program. All verbal data collection occurred at CTHS. These interactions were audio-recorded and transcribed

verbatim.

Data Analysis

Transcripts were read iteratively for relevance to the studys question. Open, line-by-line coding and

axial coding were used to analyze events, experiences, and responses. 18 A framework of categories was

developed using constant comparison.19 Consistent with theoretical sampling, analysis of essays and narrative

data continued until saturation was achieved. Management of data analysis was maintained using NVIVO 10 , a

qualitative research software program. This study received Not Regulated status from the University of

Michigan Institutional Review Board (IRB).

III. RESULTS

Our analysis revealed that high school students were motivated to participate in the DoT program to

learn about becoming a physician, gain access to individuals in medicine, and develop a competitive advantage

over other students when applying to college and medical school.

Learning About Becoming a Physician

www.ijhssi.org

34 | Page

Doctors of Tomorrow A Pipeline Program for Getting a Head Start in Medicine

At the foundation of students motivation to participate in the DoT program was their desire to learn

more about becoming a physician. Many students stated their participation was an opportunity to get hands on

information about what it takes to become a doctor. Many viewed this experience as a unique opportunity to

gain an understanding of this trajectory and obtain specific information about physicians day-to-day

responsibilities.

As far back as I can remember I have wanted to become an orthopedic surgeon. My thought was it

would be intense to go through undergrad and make it into medical school. I was sure it was going to be

extremely hard to get through 12 years of medical school. All of that changed when I was accepted into the

Doctors of Tomorrow Program. I quickly learned what striving to become a doctor looked like. I was exposed

to a real life, hands on journey into what it really takes to become a doctor. If I wasnt sure before I am

absolutely sure that a career in medicine is for me. (Critical Incident Narrative 009)

Students noted how their exposure to this program expanded their understanding of what it would be

like on the journey towards becoming a physician.

When choosing a career the choice is based on what you think [emphasis by the student] the career

entails. I have been able to experience firsthand what my life will be like as a medical student and then a

surgeon, and I like itMany have seen the various medical dramas on television and get an unrealistic view of

being a doctor. Being in this program will give a good dose of reality on what being a doctor means. (Critical

Incident Narrative 012)

Students also recognized that becoming a physician required more than getting good grades.

I felt that it would take hard work beginning now, my freshmen year of high school and throughout

my educational road to reach my goal. My eyes were opened wide that it not only takes hard work, it also takes

dedication, determination, perseverance, and sacrifice. Yes, having good grades is great but you have to have it

in your heart to help others. You must be able to reach past all barriers to reach out to help a patient. (Critical

Incident Narrative 022)

Prior to entering the program, most of the knowledge students had about the role of a physician was

based on images from popular culture or their experiences as a patient. Students desired to gain a better

perspective about the academic requirements and professional responsibilities of a career in medicine. For

many, this exposure helped them solidify their interest in medicine and better understand the trajectory from a

high school student to a physician. As such, students considered their participation as an opportunity to

determine whether medicine was the appropriatecareer path.

Gaining Access toIndividuals in the Field

It has been well documented that URiM youth lack personal experiences with medical professionals

few know or have relatives who are physicians.20Students indicated that their participation was a way to find out

what to expect from those in the fieldmedical students and physicians.

I would learn the experiences that I would possibly go through, and get advice from people who went

through it themselves. I hope to gain knowledge and insight into the life of a med student and to learn what to

expect during those years. My life goal is to become a doctor. (Application Essay 033)

Another student anticipated the taxing nature of pursuing a medical career and had the foresight to

establish a support system.I'm hoping to gain a secure relationship and receive guidancethat will help me

throughout this journey that I've chosen to take. Also, with having the opportunity to be able to have someone to

talk to with any personal problems or concerns that I may endure in learning about the world of medicine. I feel

that having the opportunity with my mentor will benefit both of us. I'll be learning new skills that I will be able

to keep with me for the rest of my life. (Application Essay 024)

The medical student mentoring and physician shadowing experiences gave participantsthe opportunity

to situate themselves within the medical context, expand their social networks, and develop experiential capital.

Developing a Competitive Advantage for the Future

Students believed that their participation in the DoT program would provide them an advantage

towards becoming a physician through additional skills and knowledge that would make them more competitive

when applying to college and medical school.

If youre in the program, youll know more than other people when they get to medical school.

Theyll ask you a question and youll already know that question that another person wouldnt know. Well be

already a step up of other medical students. So when it comes down to who gets that job, it will be a good thing

on your resume.Oh, shes been in this situation before. He knows what hes doing. (Focus Group 015)

Students also recognized the value of early high schoolpreparation as a foundation necessary for future

success.

I hope to gain more information about health and knowledge about medicine and to have a chance to

see the things I need to prepare myself for in the future. I have always dreamed of being a Pediatrician. I know

www.ijhssi.org

35 | Page

Doctors of Tomorrow A Pipeline Program for Getting a Head Start in Medicine

that being in this program; will equip me with essential knowledge to make me more prepared for this field. I

know that preparing to be a doctor will require a lot of college hours and this program will give me a head start.

(Application Essay 023)

Students also indicated that their participation would demonstrate their long-term commitment to a

career in medicine.

In one of our focus groups, one student indicated that, Were serious about what we really want to do

in our futures. Another student stated, When its time for us to submit to colleges because they can see,

starting in ninth grade that you were very serious about becoming a doctor or whatever you want to be and

theyll take us more seriously knowing that we started from a younger age. (Focus Group 007)

Students recognized the competitiveness of higher education in general, and medicine in particular, and

considered their participation in DoT asa strategy for securing targeted experiences that aligned with their long

term goal. They recognized that being a physician will require that they meet key benchmarks as well as manage

others perceptions of their abilities and commitment to medicine.

IV. DISCUSSION

This study explored high school students perceived benefits of participation in pipeline programs. The

analysis revealed that high school students with desires to become physicians sought experiences with

individuals in medicine and in medical environments with the expectation that both will put them on the path

toward becoming a physician. That includes meeting the right people and learning what it means to be a

physician. DoT participants acknowledged areas where they needed access points and opportunities to foster

growth and had informed ideas about how the pipeline program could benefit them.

Most pipeline programs are predicated on addressing academic knowledge gaps amongyouth from

URiMgroups.21 While previous efforts at increasing the diversity of the medical student population have been

aimed at providing under-represented students with academic enrichment,22 our results suggest that students

themselves believed that social and experiential capital are also important to entering the field of

medicine.23,24These findings demonstrate that students are aware of the multitude of barriers throughout the

pathway to becoming a physician even when they are not explicitly stated. Students have a long-term objective

and actively seek immediate opportunities that allow them to develop resources and skillsets to meet that goal.

Creating a pipeline from high school to medical school is an effective strategy for increasing the

number of individuals from groups underrepresented in medicine matriculates in medical school. 13 While

previous efforts at increasing the diversity of the medical student population have been aimed at providing

under-represented students with academic enrichment,22 our results suggest that students themselves believed

that social and experiential capital are also important to entering the field of medicine. 23,24 Students from lower

or middle-class backgrounds often have limited access to individuals who can help facilitate their entry into

medicine through introductions to influential people, writing letters of recommendation, providing or suggesting

internships or summer employment.25 Relationships established through programs such as DoT can increase

students access and expand their social networks.26

A key component of DoT is the mentoring relationship established between the ninth-graders and firstyear medical students. For high school students interested in pursuing careers in medicine, having access to

medical students helped maintain their interest in medicine through information about medical education, career

development, and providedanother source of social support to help facilitate this path.27,28

A limitation of this study is that students may have felt compelled to provide comments they believed

would be best received rather than what they truly believed in an effort not to appear disassociated with the

group due to social desirability bias.29 The small sample size cannot represent the interest of all URiMstudents

seeking, or entering, pipeline programs. Finally, the scope of this study did not address the long-term career

outcomes of this cohort. Hence, we cannot correlate students perceptions of the value of pipeline programs with

their career outcomes.

Our study provides insight into what students hope to achieve from pipeline programs, information that

will be essential in guiding the development of new pipeline programs and enhancing those that already exist.

Students participating in DoT indicated that they valued getting to know people involved in medicine (medical

students and physicians), gaining a better understanding of the path to becoming a doctor, and feeling that they

were one step closer to becoming a physician. Our findings suggest that pipeline programs need to expand their

focus beyond academic enrichment to also include opportunities to gainexperiential capital. As we continue to

develop and support pipeline programs designed to increase diversity in medicine, paying attention to ways to

establish relationships between students and those with the capacity to transmit resources and opportunities is

critical.

www.ijhssi.org

36 | Page

Doctors of Tomorrow A Pipeline Program for Getting a Head Start in Medicine

REFERENCES

[1].

[2].

[3].

[4].

[5].

[6].

[7].

[8].

[9].

[10].

[11].

[12].

[13].

[14].

[15].

[16].

[17].

[18].

[19].

[20].

[21].

[22].

[23].

[24].

[25].

[26].

[27].

[28].

[29].

Lucey CR. Medical Education: Part of the problem and part of the solution. JAMA Inter Med. 2013;173(17):1639-1643.

Skochelak SE. A decade of reports calling for change in medical education: What do they say? Acad Med. 2010;85(9):S26-S33.

Agrawal JR, Vlaicu S, Carrasquillo O. Progress and pitfalls in underrepresented minority recruitment: Perspectives from the

medical school. J Natl Med Assoc. 2005;97(9):1226-1231.

Garcia G, Nation CL, Parker NH. Increasing diversity in the Health Professions: A Look at Best practices in Admission. In:

Smedley BD, Butler AS, Bristow LR, eds. In the Nation's Compelling Interest: Ensuring Diversity in the Health Care Workforce.

Washington, DC: National Academy of Sciences; 2004:233-272.

Bolster L, Rourke L. The Effect of Restricting Residents' Duty Hours on Patient Safety, Resident Well-Being, and Resident

Education: An Updated Systematic Review. Journal of graduate medical education. Sep 2015;7(3):349-363.

Association of American Medical Colleges. Project 3000 by 2000 Technical Assistance Manual: Guidelines for Action.

Washington, DC1992.

Burgos JL, Lee D, Csordas T, et al. Supporting the minority physician pipeline: Providing global health experiences to

undergraduate students in the United States-Mexico border region. Med Educ Online. 2015;20(27260):1-6.

Kho AA, Verdugo B, Holmes FJ, et al. Creating an MCH pipeline for disadvantaged undergraduate students. Matern Child Health

J. 2015;19(10):2111-2118.

Edlow BL, Hamilton K, Hamilton RH. Teaching about the brain and reaching the community: Undergradutes in the pipeline

neuroscience pgoram at the University of Pennsylvania. J Undergad Neuro Educ. 2007;5(2):A63-A70.

Association of American Medical Colleges. Washington, DC: AAMC Data Warehouse Matriculant File 2012.

Association of American Medical Colleges. AAMC Matriculating Student Questionnaire 2015.

Cohen JJ, Gabriel BA, Terrell C. The case for diversity in the health care workforce. Health Aff. 2002;21(5):90-102.

Thurmond VB, Cregler LL. Why students drop out of the pipeline to health professions careers: A follow-up of gifted minority high

school students. Acad Med. 1999;74(4):448-451.

State of the Detroit Child: 2012 Report. Data Driven Detroit (D3);2012.

Macznik AK, Ribeiro DC, Baxter GD. Online technology use in physiotherapy teaching and learning: a systematic review of

effectiveness and users' perceptions. BMC medical education. 2015;15:160.

Butterfield LD, Borgen WA, Amundson NE, Maglio AT. Fifty years of the critical incident technique: 1954-2004 and beyond. Qual

Research. 2005;5:475-497.

Charmaz K. Constructing Grounded Theory. A practice guide through qualitative analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage

Publications; 2006.

Corbin J, Strauss A. Basics of qualitative research. Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. 4th ed. Thousand

Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2014.

Watling CJ, Lingard L. Grounded theory in medical education research: AMEE Guide No. 70. Med Teach. 2012;34(10):850-861.

Boateng BA, Thomas BR. Underrepresented Minorities and the Health Professions Pipeline. Acad Med. 2009;84(1):6-7.

Greenhalgh T, Seyan K, Bynton P. "Not a university type": Focus group study of social class, ethnic, and sex differences in school

pupils' perceptions about medical school. BMJ. 2004;328(7455):1541.

Patel SI, Rodriguez P, Gonzales RJ. The implementation of an innovative high school mentoring program designed to enhance

diversity and provide a pathway for future careers in heathcare related fields. J Race Ethnic Health Disparities. 2015;2(395-402).

Csizer K, Magid M, eds.: Second Language Acquisition; 2014. The Impact of Self-Concept on Language Learning.

Vaughan S, Sanders T, Crossley N, O'Neill P, Wass V. Bridging the gap: The roles of social capital and ethnicity in medical student

achievement. Med Educ. 2015;49:114-123.

Beagan BL. Everyday classism in medical school: Experiencing marginality and resistance. Med Educ. 2005;39:777-784.

Coleman JS. Social capital in the creation of human capital. Amer J Soc. 1988;94:S95-S120.

Sullivan LW. Missing Persons: Minorities in the Health Professions. The Sullivan Commission;2004.

Afghani B, Santos R, Angulo M, Muratori W. A novel enrichment program using cascading mentorship to increase diversity in the

health care professions. Acad Med. 2013;88(9):1232-1238.

Kenrick DT, Neuberg SL, Cialdini RB. Social Psychology: Unraveling the Mystery. Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon; 2002.

www.ijhssi.org

37 | Page

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Literacy Level in Andhra Pradesh and Telangana States - A Statistical StudyDocument8 pagesLiteracy Level in Andhra Pradesh and Telangana States - A Statistical StudytheijesNo ratings yet

- The Effect of Firm Size and Diversification On Capital Structure and FirmValue (Study in Manufacturing Sector in Indonesia Stock Exchange)Document12 pagesThe Effect of Firm Size and Diversification On Capital Structure and FirmValue (Study in Manufacturing Sector in Indonesia Stock Exchange)theijesNo ratings yet

- Big Data Analytics in Higher Education: A ReviewDocument8 pagesBig Data Analytics in Higher Education: A ReviewtheijesNo ratings yet

- Impact of Sewage Discharge On Coral ReefsDocument5 pagesImpact of Sewage Discharge On Coral ReefstheijesNo ratings yet

- Gating and Residential Segregation. A Case of IndonesiaDocument7 pagesGating and Residential Segregation. A Case of IndonesiatheijesNo ratings yet

- Studio of District Upgrading Project in Amman - Jordan Case Study - East District WahdatDocument5 pagesStudio of District Upgrading Project in Amman - Jordan Case Study - East District WahdattheijesNo ratings yet

- Means of Escape Assessment Procedure For Hospital's Building in Malaysia.Document5 pagesMeans of Escape Assessment Procedure For Hospital's Building in Malaysia.theijesNo ratings yet

- Defluoridation of Ground Water Using Corn Cobs PowderDocument4 pagesDefluoridation of Ground Water Using Corn Cobs PowdertheijesNo ratings yet

- A Statistical Study On Age Data in Census Andhra Pradesh and TelanganaDocument8 pagesA Statistical Study On Age Data in Census Andhra Pradesh and TelanganatheijesNo ratings yet

- Analytical Description of Dc Motor with Determination of Rotor Damping Constant (Β) Of 12v Dc MotorDocument6 pagesAnalytical Description of Dc Motor with Determination of Rotor Damping Constant (Β) Of 12v Dc MotortheijesNo ratings yet

- Data Clustering Using Autoregressive Integrated Moving Average (ARIMA) Model For Islamic Country Currency: An Econometrics Method For Islamic Financial EngineeringDocument10 pagesData Clustering Using Autoregressive Integrated Moving Average (ARIMA) Model For Islamic Country Currency: An Econometrics Method For Islamic Financial EngineeringtheijesNo ratings yet

- Industrial Installation Skills Acquired and Job Performance of Graduates of Electrical Installation and Maintenance Works Trade of Technical Colleges in North Eastern NigeriaDocument8 pagesIndustrial Installation Skills Acquired and Job Performance of Graduates of Electrical Installation and Maintenance Works Trade of Technical Colleges in North Eastern NigeriatheijesNo ratings yet

- Improving Material Removal Rate and Optimizing Variousmachining Parameters in EDMDocument5 pagesImproving Material Removal Rate and Optimizing Variousmachining Parameters in EDMtheijesNo ratings yet

- Multimedia Databases: Performance Measure Benchmarking Model (PMBM) FrameworkDocument10 pagesMultimedia Databases: Performance Measure Benchmarking Model (PMBM) FrameworktheijesNo ratings yet

- Performance Evaluation of Calcined Termite Mound (CTM) Concrete With Sikament NN As Superplasticizer and Water Reducing AgentDocument9 pagesPerformance Evaluation of Calcined Termite Mound (CTM) Concrete With Sikament NN As Superplasticizer and Water Reducing AgenttheijesNo ratings yet

- A Study For Applications of Histogram in Image EnhancementDocument5 pagesA Study For Applications of Histogram in Image EnhancementtheijesNo ratings yet

- A Lightweight Message Authentication Framework in The Intelligent Vehicles SystemDocument7 pagesA Lightweight Message Authentication Framework in The Intelligent Vehicles SystemtheijesNo ratings yet

- Experimental Study On Gypsum As Binding Material and Its PropertiesDocument15 pagesExperimental Study On Gypsum As Binding Material and Its PropertiestheijesNo ratings yet

- The Effect of Organizational Culture On Organizational Performance: Mediating Role of Knowledge Management and Strategic PlanningDocument8 pagesThe Effect of Organizational Culture On Organizational Performance: Mediating Role of Knowledge Management and Strategic PlanningtheijesNo ratings yet

- Development of The Water Potential in River Estuary (Loloan) Based On Society For The Water Conservation in Saba Coastal Village, Gianyar RegencyDocument9 pagesDevelopment of The Water Potential in River Estuary (Loloan) Based On Society For The Water Conservation in Saba Coastal Village, Gianyar RegencytheijesNo ratings yet

- Marginal Regression For A Bi-Variate Response With Diabetes Mellitus StudyDocument7 pagesMarginal Regression For A Bi-Variate Response With Diabetes Mellitus StudytheijesNo ratings yet

- Short Review of The Unitary Quantum TheoryDocument31 pagesShort Review of The Unitary Quantum TheorytheijesNo ratings yet

- Fisher Theory and Stock Returns: An Empirical Investigation For Industry Stocks On Vietnamese Stock MarketDocument7 pagesFisher Theory and Stock Returns: An Empirical Investigation For Industry Stocks On Vietnamese Stock MarkettheijesNo ratings yet

- Mixed Model Analysis For OverdispersionDocument9 pagesMixed Model Analysis For OverdispersiontheijesNo ratings yet

- The Effect of Varying Span On Design of Medium Span Reinforced Concrete T-Beam Bridge DeckDocument4 pagesThe Effect of Varying Span On Design of Medium Span Reinforced Concrete T-Beam Bridge DecktheijesNo ratings yet

- Integrated Approach To Wetland Protection: A Sure Means For Sustainable Water Supply To Local Communities of Nyando Basin, KenyaDocument6 pagesIntegrated Approach To Wetland Protection: A Sure Means For Sustainable Water Supply To Local Communities of Nyando Basin, KenyatheijesNo ratings yet

- Design and Simulation of A Compact All-Optical Differentiator Based On Silicon Microring ResonatorDocument5 pagesDesign and Simulation of A Compact All-Optical Differentiator Based On Silicon Microring ResonatortheijesNo ratings yet

- Status of Phytoplankton Community of Kisumu Bay, Winam Gulf, Lake Victoria, KenyaDocument7 pagesStatus of Phytoplankton Community of Kisumu Bay, Winam Gulf, Lake Victoria, KenyatheijesNo ratings yet

- Energy Conscious Design Elements in Office Buildings in HotDry Climatic Region of NigeriaDocument6 pagesEnergy Conscious Design Elements in Office Buildings in HotDry Climatic Region of NigeriatheijesNo ratings yet

- Evaluation of Tax Inspection On Annual Information Income Taxes Corporation Taxpayer (Study at Tax Office Pratama Kendari)Document5 pagesEvaluation of Tax Inspection On Annual Information Income Taxes Corporation Taxpayer (Study at Tax Office Pratama Kendari)theijesNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan Oral CommunicationDocument6 pagesLesson Plan Oral CommunicationBelmerDagdag100% (1)

- Session Plan: Admas University Meskel TVET College Department of Business and FinanceDocument5 pagesSession Plan: Admas University Meskel TVET College Department of Business and Financeyigrem abNo ratings yet

- Kerstin Berger Case StudyDocument4 pagesKerstin Berger Case StudySeth100% (1)

- Giver Edguide v4bDocument28 pagesGiver Edguide v4bapi-337023605No ratings yet

- The Power of Music in Our LifeDocument2 pagesThe Power of Music in Our LifeKenyol Mahendra100% (1)

- Cheyenne Miller: Cmill893@live - Kutztown.eduDocument2 pagesCheyenne Miller: Cmill893@live - Kutztown.eduapi-509036585No ratings yet

- IBDP Information Brochure 2019 - Rev 1 - 3Document12 pagesIBDP Information Brochure 2019 - Rev 1 - 3astuteNo ratings yet

- Pre-ToEIC Test 2Document28 pagesPre-ToEIC Test 2phuongfeoNo ratings yet

- Maria Montessori: My System of EducationDocument36 pagesMaria Montessori: My System of EducationAnaisisiNo ratings yet

- Project Report On Training & DevelopmentDocument47 pagesProject Report On Training & DevelopmentJakir Shajee100% (1)

- What Are The Pros and Cons of Joining in JPIA?: JPIA's Contributory Factors ACC C610-302A Group 2Document6 pagesWhat Are The Pros and Cons of Joining in JPIA?: JPIA's Contributory Factors ACC C610-302A Group 2kmarisseeNo ratings yet

- A Deep Learning Architecture For Semantic Address MatchingDocument19 pagesA Deep Learning Architecture For Semantic Address MatchingJuan Ignacio Pedro SolisNo ratings yet

- Credit Card Fraud Detection Using Machine LearningDocument10 pagesCredit Card Fraud Detection Using Machine LearningIJRASETPublicationsNo ratings yet

- Sample Quali ASMR - ManuscriptDocument26 pagesSample Quali ASMR - ManuscriptKirzten Avril R. AlvarezNo ratings yet

- Grade 5 Wetlands EcosystemsDocument4 pagesGrade 5 Wetlands EcosystemsThe Lost ChefNo ratings yet

- Week 2 Lecture Notes Fundamentals of NursingDocument8 pagesWeek 2 Lecture Notes Fundamentals of NursingGrazelle Joyce OcampoNo ratings yet

- 9 Unique Ways To Use Technology in The ClassroomDocument6 pages9 Unique Ways To Use Technology in The ClassroomAngel PendonNo ratings yet

- English Phrases For Meetings - Espresso EnglishDocument8 pagesEnglish Phrases For Meetings - Espresso Englishasamwm.english1No ratings yet

- Fieldwork Experience and Journal EntriesDocument5 pagesFieldwork Experience and Journal Entriesapi-273367566No ratings yet

- FOCUS-4 kl-12 FIRST PERIOD 2018.2019Document5 pagesFOCUS-4 kl-12 FIRST PERIOD 2018.2019ІванNo ratings yet

- Study Q's Exam 1Document3 pagesStudy Q's Exam 1Camryn NewellNo ratings yet

- A Semi-Detailed Lesson Plan in Physical Education 7: ValuesDocument3 pagesA Semi-Detailed Lesson Plan in Physical Education 7: ValuesRose Glaire Alaine Tabra100% (1)

- Pedagogy Lesson Plan-MathDocument3 pagesPedagogy Lesson Plan-Mathapi-354326721No ratings yet

- Eapp Lesson 1Document42 pagesEapp Lesson 1angelicaNo ratings yet

- PMCF LITERACY MaricrisDocument2 pagesPMCF LITERACY MaricrisRoch Shyle Ne100% (1)

- Read The Following Passage and Mark The Letter A, B, C, or D To Indicate The Correct Answer To Each of The QuestionsDocument7 pagesRead The Following Passage and Mark The Letter A, B, C, or D To Indicate The Correct Answer To Each of The QuestionsHồng NhungNo ratings yet

- Artificial Intelligence PlanDocument1 pageArtificial Intelligence PlanAhmed Osama Al-SawahNo ratings yet

- The Well Educated MindDocument8 pagesThe Well Educated Mindabuhamza_74100% (2)

- On EmpathyDocument11 pagesOn EmpathyPaulina EstradaNo ratings yet

- Questionnaire Life Long Learners With 21ST Century Skills PDFDocument3 pagesQuestionnaire Life Long Learners With 21ST Century Skills PDFHenry Buemio0% (1)