Professional Documents

Culture Documents

For Sinai Is A Mountain in Arabia A Not

Uploaded by

Alma SlatkovicOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

For Sinai Is A Mountain in Arabia A Not

Uploaded by

Alma SlatkovicCopyright:

Available Formats

DOI 10.

1515/znw-2014-0005

ZNW 2014; 105(1):80101

Stephen C. Carlson

For Sinai is a Mountain in Arabia

A Note on the Text of Galatians 4,25

Abstract: Seit Richard Bentley haben sich Textkritiker und Exegeten erstaunt ber

die Notiz in Gal 4,25a gezeigt, dass der Sinai ein Berg in Arabien ist. Frhe und

wichtige Textzeugen bieten verschiedene Lesarten, und der Satz ist in seinen vier

Hauptvarianten nicht nur grammatikalisch mit Problemen behaftet, sondern

auch im Blick auf seine Stellung in Paulus Argumentationsduktus. Der Beitrag

greift die textkritische Problematik auf und gelangt zu den folgenden Ergebnissen:

uere Bezeugung, transkriptionale Wahrscheinlichkeitserwgungen wie innere

Textkritik legen nahe, dass in V. 25a zu lesen

ist, so dass diese Lesart im kritischen Text geboten werden sollte. Darber hinaus fhren andere Hinweise zu der Annahme, dass V. 25a ursprnglich eine

Randnotiz war. Kritische Editionen sollten anzeigen, dass der Satz nicht zum ursprnglichen Haupttext des Briefes gehrt.

Stephen C. Carlson: Faculty of Theology, Uppsala University, Box 511, 751 20 Uppsala;

stephen.c.carlson@gmail.com

Three hundred years ago, Richard Bentley wrote to John Mill a letter full of philological observations in which he expressed his support for Mills project to base

an edition of the New Testament on ancient manuscripts instead of the Textus

Receptus. Recognizing that the project had been opposed as either useless or

dangerous for the church, Bentley suggested that a single passage simple on

its face but posing great difficulties beneath the surface should suffice to demonstrate the necessity for textual criticism of the New Testament. That passage is

1 R. Bentley, Epistola ad Joannem Millium, Toronto 1962, photographic reprint of A. Dyce, ed.,

The Works of Richard Bentley 2, London 1836, esp. 361365, here 362.

2 Bentley, Epistola (see n. 1), 363: operam aut inutilem esse existimant, aut Ecclesiae periculosam. Bentley has just characterized these people as inexperienced and endowed with no use

of good letters (imperiti quidam homines et nullo usu bonarum literarum praediti).

3 Bentley, Epistola (see n. 1), 363: uno exemplo quo perspicuum erit minuta qudam et

prima utique specie levissima posse magnas difficultates expedire.

Brought to you by | Uppsala University Library

Authenticated | 130.238.69.12

Download Date | 2/20/14 11:46 AM

For Sinai is a Mountain in Arabia

81

Pauls allegory of Sarah and Hagar in Gal 4,2226, which Bentley knew from the

Textus Receptus in the following form:

22 , ,

. 23 , ,

. 24

, , . 25

, , . 26

, .

22 For it is written that Abraham had two sons, one from the slave girl, and one from the

free woman. 23 But the one from the slave girl was born according to the flesh, while the

one from the free woman [was born] through the promise. 24 These things are allegorized:

for these are two covenants. On the one hand, one from Mount Sinai, giving birth into slavery, who is Hagar. 25 For this Hagar is the Sinai mountain in Arabia, but it corresponds

to the present Jerusalem, and she is enslaved with her children. 26 On the other hand, the

Jerusalem above is the free woman, who is the mother of all of us.

Bentley thought it did not make sense for Paul to call the same mountain both

Sinai and Hagar (a name attested nowhere else for a mountain) nor for Hagar

to correspond to both the mountain and the law promulgated from it. To deal

with these problems, Bentley proposed that the part of the sentence

was not from Paul at all but a marginal note that crept into the

body of the text. Objecting to the neuter article in front of the feminine ,

Bentley further surmised that the syntax of what Paul originally wrote must have

been distorted when the note was incorporated into the main text. Accordingly,

Bentley conjectured that Pauls text in Gal 4,25 had actually read:

4 The 27th edition Nestle-Aland critical text (hence NA27) does not include this article on the

strength of P46 01 A C 33 81 104 1241s and a few others; the 25th edition, however, included the

article with B D F G 1739 Byz and Origen. The text of the most recent 28th edition is the same in

Galatians, though the apparatus has been revised.

5 NA27 reads instead of , and some important witnesses do not include the following .

6 NA27 does not add based on the very strong external evidence of P46 01* B C* D F G

33 1241s 1505 1739, Marcion according to Tertullian, and Origen.

7 Bentley, Epistola (see n. 1), 363: neque enim eundem montem et Agarem vocatum esse et

Sinam, neque vero ullum usquam gentium eo nomine notatum esse, neque porro Agarem servam (si de serva malit quispiam, quam de monte accipere) in eadem allegoria et monte respondere posse, et legi qu ex monte promulgata est.

8 Bentley, Epistola (see n. 1), 364: ea autem verba non multo post, ut saepe usu venit, de libri margine in orationem ipsam irrepsisse: nam Apostoli quidem ea non esse, sed ,

9 Bentley, Epistola (see n. 1), 365: aut quamobrem genere neutro posuit; quasi vero

materialiter ac pro voce, non pro ancilla, hic usurpetur?

Brought to you by | Uppsala University Library

Authenticated | 130.238.69.12

Download Date | 2/20/14 11:46 AM

82

Stephen C. Carlson

, (But to Hagar

corresponds the present Jerusalem, for she is enslaved with her children).

Now Bentleys conjecture has been abandoned by subsequent scholars (including himself apparently) and misrepresented in the NA27 apparatus, but

the exegetical problems with Gal 4,25a remain. Hans Dieter Betz called it a real

crux interpretum, and commentators routinely note that the geographic note is

difficult to understand in its context. Modern-day exegetes are not the only ones

who found the text difficult. Ancient scribes too were perplexed. In particular

they had trouble deciding whether the conjunction was or , and whether

to include or omit . To take Bentleys text-critical challenge seriously, text

critics must consider five forms of the Greek text within the textual history of

Gal 4,25a. In particular, the textual critic should construe the major textual

variants in Gal 4,25a within the context of the entire passage, and, based on this

10 Bentley, Epistola (see n. 1), 365.

11 Inferred from the fact that Bentley later did not mention his conjecture in either the text or

the apparatus of his edition of Galatians (R. Bentley, Epistola beati Pauli Apostoli ad Galatas, in:

A.A. Ellis, Bentleii Critica Sacra: Notes on the Greek and Latin Text of the New Testament, Extracted from the Bentley Mss. in Trinity College Library, Cambridge 1862, 93117, esp. 108109).

See also J.B. Lightfoot, St. Pauls Epistle to the Galatians, Peabody 1995, 193.

12 The NA27 apparatus mistakenly indicates that Bentleys conjecture is the omission of the

entire clause, . The actual originator of this conjecture

is H.A. Schott, Epistolae Pauli ad Thessalonicenses et Galatas (Commentarii in Epistolas Novi

Testamenti 1), Leipzig 1834, 533. Thanks to J. Krans (pers. comm.) for alerting me to this reference.

13 H.D. Betz, Galatians: A Commentary on Pauls Letter to the Churches in Galatia (Hermeneia),

Philadelphia 1979, 244.

14 In addition to Betz, so also M.C. de Boer, Pauls Quotation of Isaiah 54.1 in Galatians 4.27, NTS

50 (2004) 370389, esp. 375 n.19: this half-verse has proved notoriously difficult to understand;

J.L. Martyn, Galatians (AncB 33A), New York 1997, 437: the line of Pauls thought in this verse is

difficult to grasp; U. Borse, Der Brief an die Galater (RNT), Regensburg 1984, 169170: Der Satz

ber den Berg Sinai und Arabien bereitet der Auslegung besondere Schwierigkeiten; B.F. Westcott and F.J.A. Hort, Introduction to the New Testament in the Original Greek, Peabody, Mass.

1998, App. 121: perplexing and hard to interpret.

15 The five Greek forms of Gal 4,25a are set forth in K. Aland et al. (eds.), Text und Textwert der

griechischen Handschriften des neuen Testaments: II. Die paulinischen Briefe. Band 3: Galaterbrief bis Philipperbrief (ANTF 18), Berlin 1991, 159161. See also R.J. Swanson, New Testament

Greek Manuscripts: Galatians, Wheaton, Ill. 1999, 59. Some manuscripts, however, omit the crucial words due to parablepsis. For example, 1573 skips from the in v. 24 to the in v. 25,

omitting the words . As another example,

999 and 1963 skip from in v. 24 to the in v. 25, omitting the words

. Still another seven witnesses, 61* 90 465* 1243 1352 1874* 2344, skip from

to , omitting the words . Franz Muner, Der Galaterbrief (HThK 9), Freiburg etc.

1974, 322, lists some additional versional and patristic forms that are unlikely to go back to Paul.

Brought to you by | Uppsala University Library

Authenticated | 130.238.69.12

Download Date | 2/20/14 11:46 AM

For Sinai is a Mountain in Arabia

83

exegesis, balance both the external evidence for the variants and the internal evidence in terms of their transcriptional and intrinsic probabilities to ascertain the

oldest recoverable form of the text.

1The Texts of Galatians 4,25a

I. (Now this Hagar is the Sinai

mountain in Arabia). This is the reading of the NA27 critical text, and it has

been accepted by most recent commentators. It enjoys the support of the fourthcentury Codex Vaticanus (B), the fifth-century Codex Alexandrinus (A), and the

sixth-century Codex Claromontanus (D), along with scattered minuscules.

This reading presents a number of delicate exegetical decisions. One of them

is that there are three nominative nouns in a linking clause that normally takes

two: , , and . At least one of them must be an attributive noun (i.e.,

used adjectivally) or a noun in apposition. James D. G. Dunn, for example, has

argued that Hagar should be considered adjectival, thereby construing

as the Hagar-Sinai, in reference to Pauls identification of Hagar and

the Sinai covenant in v. 24. The difficulty with this proposal, however, is that the

16 For an overview of the modern praxis of textual criticism, see B.M. Metzger, The Text of the

New Testament: Its Transmission, Corruption, and Restoration, New York/Oxford 31992, 207246;

K. Aland / B. Aland, The Text of the New Testament: An Introduction to the Critical Editions

and to the Theory and Practice of Modern Textual Criticism, Grand Rapids, Mich. 21989, 280297;

and M.W. Holmes, Reasoned Eclecticism in New Testament Textual Criticism, in: B.D. Ehrman /

M.W. Holmes (eds.), The Text of the New Testament in Contemporary Research: Essays on the

Status Quaestionis (SD 46), Grand Rapids, Mich. 1995, 336360.

17 B.M. Metzger, A Textual Commentary on the Greek New Testament, Stuttgart 21994, 527.

18 Including Martyn, Galatians (see n. 14), 432.437438; J.D.G. Dunn, The Epistle to the Galatians

(BNTC), London 1993, 242.250252; F.J. Matera, Galatians (Sacra Pagina 9), Collegeville, Minn.

1992, 167170; F.F. Bruce, The Epistle to the Galatians: A Commentary on the Greek Text (NIGTC),

Grand Rapids, Mich. 1982, 219; Betz, Galatians (see n. 13), 244245; and Muner, Galaterbrief (see

n. 15), 316.320324.

19 According to B. Aland et al., The Greek New Testament, Stuttgart 41994, 648, they are: 256 365

436 1175 1319 1962 2127 2464. This edition will be referred to as UBS4.

20 It is faintly possible that could be in the genitive case, though it would have been

clearer to include the article like this: .

21 Dunn, Galatians (see n. 18), 251, endorsed later by S.M. Elliott, Choose Your Mother, Choose

Your Master: Galatians 4:215:1 in the Shadow of the Anatolian Mother of the Gods, JBL 118 (1999)

661683, esp. 668. Dunn confusingly characterizes his proposal as tak[ing] Hagar and Sinai

in apposition (Hagar as adjectival) (251).

Brought to you by | Uppsala University Library

Authenticated | 130.238.69.12

Download Date | 2/20/14 11:46 AM

84

Stephen C. Carlson

rest of the clause, needs a subject that can be equated

to a mountain in Arabia. Similarly, Andrew C. Perriman takes both Hagar and

Sinai to be adjectival so that the clause means the Hagar-Sinai mountain is in

Arabia, but this requires an unusual nominal construction with three nouns

in a row.

The least problematic of the options, though, is to take Sinai as attributive, so should mean the Sinai mountain (or Mount Sinai), and the

whole clause means Hagar is the Sinai mountain in Arabia. The hyperbaton

of placing before the verb and the prepositional phrase

afterwards suggests that the point of the clause is to identify Hagar with the Sinai

mountain. The main problem with this analysis, however, is that the word order

for Mount Sinai is rather unusual. The word order of the LXX is consistently , and, in fact, Paul had just used the usual order in the preceding

verse ( ).

22 S. Di Mattei, Pauls Allegory of the Two Covenants (Gal 4.2131) in Light of First-Century Hellenistic Rhetoric and Jewish Hermeneutics, NTS 52 (2006) 102122, further rejects the HagarSinai amalgam as just not an acceptable rendering of the Greek (111) and suspicious on the

grounds that it seems guided by underlying typological presuppositions (111 n.34).

23 A.C. Perriman, The Rhetorical Strategy of Galatians 4:215:1, EvQ 61 (1993) 2742, esp. 3738,

calling Hagar-Sinai a composite reference to the conceptual fusion of the allegory.

24 Indeed, Perriman concedes that no example of a comparable nominal expression is forthcoming (Rhetorical Strategy [see n. 23], 38 n.26). Another possibility for construing the three

nominatives would be to understand in apposition to ; hence, would be

translated as Sinai, a mountain. Thus, would be the subject and

(is Sinai, a mountain in Arabia) would be the predicate. An objection to this reading is

that occurs between and and interrupts the appositional noun phrase.

25 E.g., Martyn, Galatians (see n. 14), 432.437; Matera, Galatians (see n. 18), 167.169; R.N. Longenecker, Galatians (WBC 41), Dallas 1990, 198; Borse, Galater (see n. 14), 168170; Bruce, Galatians

(see n. 18), 219; Betz, Galatians (see n. 13), 244; A. Oepke, Der Brief des Paulus an die Galater

(ThHK 9), Berlin 21957, 109; and E.d.W. Burton, A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on the Epistle to the Galatians (ICC), Edinburgh 1921, 258.

26 The separation of a noun phrase by the verb lends more emphasis to one of the parts; see

generally H. Smith, Greek Grammar, Cambridge, Mass. 1920, 679 3028 (as hyperbaton) and

S.H. Levinsohn, Discourse Features of New Testament Greek: A Coursebook on the Information

Structure of New Testament Greek, Dallas 22000, 5760 (as discontinuous constituent).

27 Exod 19,11.16.18.20.23; 24,46; 31,18; 34,2.2.32; Lev 7,38; 25,1; 26,46; 27,34; Num 3,1; 28,6; 2Esdr

19,13; cf. Acts 7,30.38. Note however that Josephus prefers the form , with a declinable form of the mountains name.

28 S. Lgasse, Lptre de Paul aux Galates (LeDiv.Comm. 9), Paris 2000, 355; Elliott, Choose (see

n. 21), 668; Dunn, Galatians (see n. 18), 250; and G.I. Davies, Hagar, El-Hera and the Location of

Mount Sinai, VT 22 (1972) 152163, esp. 159 n.4.

Brought to you by | Uppsala University Library

Authenticated | 130.238.69.12

Download Date | 2/20/14 11:46 AM

For Sinai is a Mountain in Arabia

85

Another exegetical task is to determine why the feminine takes the neuter article . Although unusual, most exegetes have been able to account for

this lack of grammatical concord in gender by appealing to a quotative usage of

the neuter article, or supposing that it refers here to the name (i.e., )

Hagar, rather than to the woman. As a result, the phrase ought to be

translated as something like the [name] Hagar or this Hagar, and the clause

as a whole can be rendered this Hagar is Sinai mountain in Arabia.

As for the conjunction , it does not coordinate with the in the preceding verse, , , , because the resulting construction entails that the clause refers to the

other covenant, which Gal 4,25a does not. In fact, it is only much later at v. 26

that Paul gets to expounding the other covenant:

, , and even here it does not present a precisely parallel construction to the clause. Similarly, the conjunction is not used

adversatively, because the information given in v. 25a does not contrast with that

in v. 24; rather, v. 25a gives more information, so the conjunction is best considered connective.

The exegetical decisions are not restricted to deciding the meaning inside

the clause but also involve figuring out the clauses relationship to the context.

In v. 24, Paul had just equated the covenant from Mount Sinai with Hagar, so it

is startling to find Hagar being re-identified with Sinai itself. Whatever the reasons for this shift in the identification of Hagar, it seems to have something to do

29 E.g., Perriman, Rhetorical Strategy (see n. 23), 37: puzzling and requires explanation. Also

Bentley, Epistola (see n. 1), 365.

30 F. Blass / A. Debrunner / R.W. Funk, A Greek Grammar of the New Testament and Other

Early Christian Literature, Chicago 1961, 140 at 267(1). So also Martyn, Galatians (see n. 14),

437 n.132; G. Sellin, Hagar und Sara. Religionsgeschichtliche Hintergrnde der Schriftallegorese

Gal 4,2131, in: Das Urchristentum in seiner literarischen Geschichte. FS Jrgen Becker (BZNW

100), Berlin 1999, 5984, esp. 74; and D.-A. Koch, Die Schrift als Zeuge des Evangeliums: Untersuchungen zur Verwendung und zum Verstndnis der Schrift bei Paulus (BHTh 69), Tbingen

1986, 206 n.18.

31 E.g., Lgasse, Galates (see n. 28), 354 n.5; and Betz, Galatians (see n. 13), 244 n.65.

32 Muner, Galaterbrief (see n. 15), 320, argues that the structure of Pauls argument is as if he

wrote: , ,

.

33 So H. Ridderbos, The Epistle of Paul to the Churches of Galatia (NIC), Grand Rapids, Mich.

1953, 178 n.9. Also Lgasse, Galates (see n. 28), 356 n.1; Martyn, Galatians (see n. 14), 438; Longenecker, Galatians (see n. 25), 198 n.d; and Betz, Galatians (see n. 13), 244.

34 Perriman, Rhetorical Strategy (see n. 23), 37; Dunn, Galatians (see n. 18), 250.

Brought to you by | Uppsala University Library

Authenticated | 130.238.69.12

Download Date | 2/20/14 11:46 AM

86

Stephen C. Carlson

with the fresh information of being located in Arabia, and theories abound

as to the reason why. Perhaps it is because Hagar is the mother of the Arabs

(cf. Gen 25,1218 and the Hagarites in Ps 83,6). Other critics connect Hagar with

an Arabian town of a similar name or with Hegra in the Targums. Another

possibility is that Hagar sounds like adjar, the Arabic word for rock. The

common difficulty with all these theories is that they explain the obscure by the

more obscure. There is no actual evidence that Paul knew any of these Arabic

meanings for Hagar, much less the Arabic language, nor is there any hint that it

would have been comprehensible for Pauls Galatian audience.

II. (For this Hagar is the Sinai

mountain in Arabia). This is the reading of the Byzantine text and the Textus

35 So D. Snger, Sara, die Freie unsere Mutter: Namenallegorese als Interpretament christlicher Identittsbildung in Gal 4,2131, in: Neues Testament und hellenistisch-jdische Alltagskultur (WUNT 274), ed. R. Deines / J. Herzer / K.-W. Niebuhr, Tbingen 2011, 213239, esp. 222.

Elliott, Choose (see n. 21), argues that the connection between Hagar and Sinai is to facilitate a

comparison to a Mountain Mother familiar to the Galatians, but her proposal can only account

for the mention of in Arabia as an incidental detail (678 n.59).

36 Dunn, Galatians (see n. 18), 251252, outlines various possibilities before conceding that the

exact meaning remains obscure (quoting H. Schlier).

37 Snger, Sara (see n. 35), 222; Martyn, Galatians (see n. 14), 438 n.136; Matera, Galatians (see

n. 18), 170; Koch, Schrift (see n. 30), 207 n.22; E. Lohse, Art. , TDNT 7 (1971) 282287, esp.

286; H. Schlier, Der Brief an die Galater (KEK 7), Gttingen 101949, 156; M.-J. Lagrange, Saint Paul:

ptre aux Galates (EtB), Paris 21925, 125.

38 A.M. Schwemer, Himmlische Stadt und himmlisches Brgerrecht bei Paulus (Gal 4,26

und Phil 3,20), in: La Cit de Dieu / Die Stadt Gottes (WUNT 129), hg. v. M. Hengel / S. Mittmann

/ A.M. Schwemer, Tbingen 2000, 195243, here 200; M. McNamara, to de (Hagar) Sina oros

estin en t Arabia (Gal. 4:25a): Paul and Petra, Milltown Studies 2 (1978) 2441; and H. Gese,

(Gal 4 25), in: Das ferne und nahe Wort. FS Leonhard Rost

(BZAW 105), Berlin 1967, 8194. For an opposing view see Davies, Hagar (see n. 28).

39 M.G. Steinhauser, Gal 4,25a: Evidence of Targumic Tradition in Gal 4,2131?, Bib. 70 (1989)

234240.

40 E.g., Betz, Galatians (see n. 13), 245 (notwithstanding the difference in the initial consonant).

Still others have proposed a Hebrew wordplay between Hagar and the Hebrew for the mountain, ha har (e.g. A.F. Puukko, Paulus und das Judentum, StOr 2 [1928] 181, esp. 7 and 75). The

difficulty with this explanation, however, is that there is nothing in the Hebrew to account for the

inclusion of the notice in Arabia.

41 J. Rohde, Der Brief des Paulus an die Galater (ThHK 9), Berlin 1988, 199: Aber Paulus konnte

nicht erwarten, da er seinen galatischen Lesern durch diese Beweisfhrung den Zusammenhang des Alten Bundes mit Hagar htte beweisen knnen, weil sie ihnen in dieser Kurzform

unverstndlich bleiben mute.

Brought to you by | Uppsala University Library

Authenticated | 130.238.69.12

Download Date | 2/20/14 11:46 AM

For Sinai is a Mountain in Arabia

87

Receptus. It has the support of the majority of manuscripts, including (a ninthcentury manuscript on Mount Athos) and the Queen of the Minuscules, 33; in

addition, this variant is read by Chrysostom. The difference between this variant and the preceding one is the use of the conjunction instead of . As such,

the conjunction is more specific about the function of Gal 4,25a. It gives the

reason why the covenant from Mount Sinai is Hagar.

III. (This Hagar is the Sinai mountain in Arabia). According to Text und Textwert, only two manuscripts, 228 and

2004, support this reading. This reading differs from the preceding two in its

use of asyndeton instead of a conjunctive particle to join this clause to Pauls

argument. Though asyndeton is an unmarked connective, its use in preference

to another connective particle tends to signal either a larger discontinuity such

as a change in topic for the argument or a very close connection to the previous

statement. It is the latter interpretation that would be more appropriate here.

IV. (For Sinai is a mountain in

Arabia). Prior to the mid-20th century, this was the reading favored by many

critics not dependent on the Textus Receptus, including Westcott, Tischendorf,

Lightfoot, Lachmann, and Bentley after he abandoned his conjecture. Even

today, it enjoys support among some exegetes. In the manuscript tradition, this

42 Not surprisingly, this Byzantine variant is adopted by H. von Soden, Die Schriften des Neuen

Testaments, Gttingen 1913, 756. The only recent scholar I could find to adopt this variant is Di

Mattei, Pauls Allegory (see n. 22), 111 n.35. P. Bonnard, Lptre de Saint Paul aux Galates (CNT 9),

Neuchtel 21972, 97, though claiming to adopt the reading of the Nestle critical text, interprets

the text as if the conjunction has the same explicative meaning as .

43 UBS4, 648.

44 Steinhauser, Gal 4,25a (see n. 39), 234.

45 Aland, Text und Textwert (see n. 15), 160. The only exegete I have been able to find to discuss

this reading is Sellin, Hagar und Sara (see n. 30), 7374, who duly cites Text und Textwert.

46 Levinsohn, Discourse Features (see n. 26), 118119. See also S.E. Runge, A Discourse Grammar of the Greek New Testament: A Practical Introduction for Teaching & Exegesis (Lexham Bible

Reference Series), Bellingham, Wash. 2010, 36. On Pauls use of asyndeton, especially in Romans

and both Corinthian letters, see generally E.W. Gtig / D.L. Mealand, Asyndeton in Paul: A TextCritical and Statistical Enquiry into Pauline Style (SBEC 39), Lewiston, N.Y. 1998.

47 Westcott, Introduction (see n. 14), App. 121, disagreeing with Hort; C. Tischendorf, Novum

Testamentum Graece 2, Leipzig 81869, 648; Lightfoot, Galatians (see n. 11), 181; K. Lachmann,

Novum Testamentum Graece et Latine 2, Berlin 1850, 449; Bentley, Galatas (see n. 11), 108. The

reason why Bentley abandoned his earlier conjecture is not hard to fathom. By adopting the

reading of C and the Vulgate without the word Hagar (Sinaiticus had not yet been discovered),

Bentley was able to obviate his original objections to the wording of the Textus Receptus.

48 E.g., Lgasse, Galates (see n. 28), 354.356; N.T. Wright, Paul, Arabia, and Elijah (Galatians

1:17), JBL 115 (1996) 683692, esp. 686; and Borse, Galater (see n. 14), 168170.

Brought to you by | Uppsala University Library

Authenticated | 130.238.69.12

Download Date | 2/20/14 11:46 AM

88

Stephen C. Carlson

reading is supported by the fourth-century Codex Sinaiticus (), the fifth-century

Codex Ephraemi rescriptus (C), the ninth-century Old Latin bilingual codices F

and G, and the important minuscules 1241 and 1739. It is also found in most of the

Old Latin manuscripts, the Vulgate, and various Western Fathers.

The syntax within the clause offers two possibilities. First, the collocation

could be the subject and the clause as a whole would mean For the

Sinai mountain is in Arabia. The main difficulty with this possibility is that the

word order to mean Mount Sinai is unusual, as explained above. The other

possibility is that the noun functions as a predicate to in hyperbaton

with its attributive preposition phrase positioned after the copula.

Thus, the neuter article construes directly with the neuter proper noun

to form the subject of the clause, and the predicate is .

As such, the whole clause can be rendered: For Sinai is a mountain in Arabia.

Outside the clause, however, the reading is more difficult to understand because it seems to have little to do with the context. C. K. Barrett, for example,

called it a bare piece of geographic information of little interest to the readers

or relevance to the context. The causal conjunction may indicate that the

Arabian location of Mount Sinai has something to do with the identification of

the covenant promulgated from that mountain with Hagar, but the connection

is not explicit. Perhaps, the placement of the notice immediately after the name

Hagar is to imply that Hagar somehow relates to the geographical reason in the

clause. If so, then the exegete is left with the same quandary as in the longer reading with the explicit Hagar the connection between Hagar and Sinai in Arabia

could be due to Hagar being the ancestor of the Arabs through Ishmael, or that

Hagar sounds like some Arabic word related to Mount Sinai.

Another possibility is to construe the geographic notation, not with the immediately preceding Hagar, but with the statement about the Sinai covenants engendering slavery, . The purpose, then, of specifying that

49 UBS4 lists ar, b, f, g, o, r, and Victorinus of Rome, Jerome, Pelagius, and Augustine.

50 Pace Borse, Galater (see n. 14), 168.

51 E.g., Lgasse, Galates (see n. 28), 356; Martyn, Galatians (see n. 14), 437; and Longenecker,

Galatians (see n. 25), 198 n.e.

52 C.K. Barrett, The Allegory of Abraham, Sarah, and Hagar in the Argument of Galatians, in:

Rechtfertigung. FS Ernst Ksemann, Tbingen 1976, 116, esp. 12. Also Lohse, Art. (see n. 37),

285: But in the context of the whole passage this kind of note hardly yields a satisfying sense;

Oepke, Galater (see n. 25), 112: Als rein geographische Notiz ist das Stzchen vollends unertrglich; and Schlier, Galater (see n. 37), 156: Eine blo geographische Zwischenbemerkung

wre an dieser Stelle sinnlos.

53 Lgasse, Galates (see n. 28), 356.

Brought to you by | Uppsala University Library

Authenticated | 130.238.69.12

Download Date | 2/20/14 11:46 AM

For Sinai is a Mountain in Arabia

89

Sinai is a mountain in Arabia is to underscore that it is outside the territory of the

Promised Land. This possible interpretation founders, however, because Paul

goes on to explain in v. 25bc that the Hagar covenant corresponds to present-day

Jerusalem for she is enslaved with her children, ,

. By this reasoning, earthly geography is irrelevant to bondage, and hence the geographical notice can hardly contribute to

his argument.

V. (Now Sinai is a mountain in Arabia).

This is actually the oldest attested reading, found in the turn-of-the-third-century

Chester Beatty Papyrus of Pauls letters (P46), but it is otherwise poorly attested,

being limited to a few versional and patristic witnesses. Despite its meager attestation, this reading has found the support of two modern scholars.

This reading differs from the preceding one in its use of the conjunction

instead of . Although the content of the clause is nearly the same, pointing out

that Sinai is a mountain in Arabia, the different conjunction causes the clause to

interact with the context in a different way. Rather than giving a reason for the

identification of Hagar and the Sinai covenant in v. 24 as the causal conjunction

would indicate, the content of v. 25 with the conjunction interacts with

the remainder of the verse that sets up the allegorical correspondence with the

present-day Jerusalem. Under this interpretation, v. 25 as a whole would mean:

while Sinai geographically is in Arabia, it allegorically corresponds to the present

Jerusalem . As a result, the conjunction in v. 25a is not meant to explain

why Hagar is to be identified with the Sinai covenant but to carry the allegory

54 Lgasse, Galates (see n. 28), 357, who further claims that this interpretation is sufficient to

obviate the objection that Gal 4,25a is a pure geographic notation (356 n.7). This interpretation is

fairly old, for in 1834 Schott, Epistolae Pauli (see n. 12), 532, had already attributed this view to

J.S. Semler and G.T. Zachariae.

55 Ridderbos, Galatia (see n. 33), 177178 n.9: Jerusalem, in the heart of the promised land,

could not grant freedom either.

56 UBS4 lists P46, some manuscripts of the Vulgate, the Sahidic, a Latin translation of Hesychius, and Ambrosiaster.

57 A. Kerkeslager, Jewish Pilgrimage and Jewish Identity in Hellenistic and Early Roman Egypt,

in: Pilgrimage and Holy Space in Late Antique Egypt, ed. D. Frankfurter, Leiden, 1998, 99225,

esp. 180187, here 182186; and F. Muner, Hagar, Sinai, Jerusalem, ThQ 135 (1955) 5660. See

also, Muner, Galaterbrief (see n. 15), 324.

58 Muner, Galaterbrief (see n. 15), 324; and Muner, Hagar (see n. 57), 5960: Gewi liegt das

Sinaigebirge, geographisch gesehen, in der Arabia; in Wirklichkeit aber, fr mein allegorisches

Verstndnis, entspricht es dem heutigen Jerusalem (emphasis and footnotes removed).

Brought to you by | Uppsala University Library

Authenticated | 130.238.69.12

Download Date | 2/20/14 11:46 AM

90

Stephen C. Carlson

forward to the next point of comparison. A problem with such an interpretation,

however, lies in the third clause of v. 25: .

This clause needs to take up Hagar, not Sinai, as its animate subject.

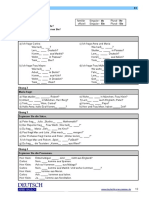

2External Evidence

One of the reasons why the textual criticism of Gal 4,25a is so challenging is that

the external evidence does not line up neatly with the variant readings, as can be

seen in the following chart:

Alexandrian61

Reading

I.

II.

III.

Primary

Secondary

A

33

Western

Byzantine

pc

(d)

62

M

228 2004

IV.

C 1241 1739 F G ar b vg

V.

P46

sa

In terms of external evidence, one of the readings can be set aside immediately.

The asyndetonic reading III ( ) is attested in only two, fairly late man-

59 As explained above with respect to reading A ( ), the is neither adversative nor picks up the to create a construction.

60 E.g., Martyn, Galatians (see n. 14), 438: But how would a conclusion involving slavery be

drawn if there was not a preceding reference to the slave Hagar? In short, Paul connects Jerusalem with slavery by saying that this Jerusalem stands in the same oppositional column with the

slave Hagar, thus being connected via Hagar with the enslaving covenant of Sinai.

61Primary and secondary Alexandrian correspond to Metzgers proto-Alexandrian and lesser

Alexandrians, respectively. Metzger, Text (see n. 16), 216. Gnter Zuntz, The Text of the Epistles:

A Disquisition upon the Corpus Paulinum, London 1953, 158159, has a similar theory of the text

in Paul, except that he promotes 1739 to the primary, proto-Alexandrian status and demotes

to his Lesser Alexandrian category. Based on the pattern of attestation in this case, the difference between Metzgers and Zuntzs classification does not materially affect the analysis.

62Old Latin manuscript d omits / Sina.

63 As did Sellin, Hagar und Sara (see n. 30), 74 n.37: Lesart (5) [scil. ] ist so schwach

bezeugt, da sie unbercksichtigt bleibt.

Brought to you by | Uppsala University Library

Authenticated | 130.238.69.12

Download Date | 2/20/14 11:46 AM

For Sinai is a Mountain in Arabia

91

uscripts housed in the Escorial library in Spain: 228 and 2004. They are so late

and removed from the archetype that their readings here can be true only by an

accidental coincidence.

As for the rest of the readings, the manuscript evidence is spread among them.

In terms of age and weight, the weakest reading among the remaining four is, in

fact, the reading that is the most prevalent through the Byzantine manuscripts:

reading II ( ): it does not enjoy any support from the Primary

Alexandrians and has limited attestation among the Secondary Alexandrians

and Western witnesses. Conversely, if the most numerous reading happens to be

the youngest, the earliest reading, V ( ), just so happens to be the most

poorly attested among Greek manuscripts it is limited to P46 (c. 200).

The other two readings have stronger attestation among the manuscripts, but

the weight is almost evenly balanced between them. On the one hand, reading

I ( ) is supported by the Primary Alexandrian B, the Secondary

Alexandrian A, and the Western D plus a few Byzantine manuscripts. On the

other hand, reading IV ( ) can count on the Primary Alexandrian , the

Secondary Alexandrian C 1241s 1739, and the Western F G ar b vg. In other words,

all the major, non-Byzantine text-types are split among readings I (

) and IV ( ). If anything, the support for reading IV ( ) is

slightly stronger among the Secondary Alexandrian and Western groups, because

multiple members of those text-types support the reading, while reading I (

) benefits only from a single witness in each, A and D respectively,

suggesting that their agreement on this reading may be due to accidental coincidence rather than through inheritance.

In fact, there is evidence that the reading in D is secondary within its own

tradition and therefore not a witness to the earliest reading. H. J. Vogels has called

attention to the fact that, though D is usually arranged with a sense unit per line,

the present text departs from the arrangement by breaking 4,25a in an unusual location: / . The words at the end

of the line are not paralleled in the corresponding Latin column of d. Moreover,

64 Aland, Text und Textwert (see n. 15), 160. According to K. Aland, Kurzgefate Liste der griechischen Handschriften des Neuen Testaments (ANTT 1), Berlin 21994, 60 and 161, respectively.

Gregory-Aland 228 (von Soden 458; shelf mark . IV. 12) is a fourteenth-century paper manuscript, and Gregory-Aland 2004 (von Soden 56; shelf mark . III. 17) is a twelve-century parchment manuscript.

65 H.J. Vogels, Der Codex Claromontanus der paulinischen Briefe, in: Amicitiae Corolla. FS

James Rendel Harris, ed. H.G. Wood, London 1933, 274299, esp. 294. So also K.T. Schfer, Der

griechisch-lateinische Text des Galaterbriefes in der Handschriftengruppe D E F G, in: Scientia

Sacra, ed. C. Feckes, Kln 1935, 4170, esp. 6263.

Brought to you by | Uppsala University Library

Authenticated | 130.238.69.12

Download Date | 2/20/14 11:46 AM

92

Stephen C. Carlson

the Latin on the following sense-line also reads enim, which corresponds to the

Greek . This evidence suggests that the at the end of the line had been

added there in Ds exemplar, and the word had been deleted. Vogels concludes that Ds exemplar originally agreed with F and Gs reading IV ( ).

Thus, the weight of D as evidence for reading I ( ) ought to be discounted.

Given the split of witnesses for reading I ( ) and reading IV (

), it is tempting to use P46 to cast the tie-breaking vote. A complicating

factor is that P46s own reading V ( ) is an intermediary between the two

best supported readings: on the one hand, it supports the conjunction as in

reading I ( ), but, on the other hand, it bears witness to the lack of

Hagar as in reading IV ( ). If P46 is used to decide both sub-variation

units separately, then the result of this procedure would be P46s own reading,

because the result would include both the conjunction and the shorter reading

without Hagar. Furthermore, if P46 is used to decide the priority of either reading A or reading C based on just one of the sub-variation units, then the choice

of variation unit will dictate the result. For example, Bruce Metzgers analysis

of this variant in his Textual Commentary focuses on the conjunction to decide

between readings I and IV; since P46 has the conjunction , then reading I, also

with the conjunction , is awarded priority. Yet it is unclear why the preference

should be given to the sub-variation unit concerning the conjunction. Surely, the

inclusion or omission of the name Hagar is exegetically more significant and

more pertinent to why a scribe would modify the text. Moreover, P46s inclusion

of instead of means that Metzgers reasoning that was accidentally

omitted by homoioteleuton in the sequence cannot account for P46s

own lack of . Indeed, as Ian Moir put it, P46 had no and still got rid of

Hagar! If the sub-variation unit concerning Hagar is used for the tie-breaking

vote, then P46s witness would favor reading IV ( ) instead.

66 Incidentally, the Byzantine reading II ( ) is also mid-way between the two

readings, giving rise to the similar methodological problems if the Byzantine text is to be used

for a tie-breaking vote.

67 This is basically the procedure that led Kerkeslager, Jewish Pilgrimage (see n. 57), 185, to

decide in favor of P46s reading as the original form of v. 25a.

68 Metzger, Textual Commentary (see n. 17), 527: As between and , the Committee preferred the former on the strength of superior attestation (P A B Dgr syrhmg, pal copsa, bo). After

had replaced in some witnesses, the juxtaposition of led to the accidental omission

sometimes of and sometimes of .

69 I. Moir, Review of A Textual Commentary on the Greek New Testament by Bruce M. Metzger

(1971), BiTr 24 (1973) 329333, here 332. Moirs comment was quoted with approval by J.C.ONeill,

Brought to you by | Uppsala University Library

Authenticated | 130.238.69.12

Download Date | 2/20/14 11:46 AM

For Sinai is a Mountain in Arabia

93

At any rate, the external evidence for Gal 4,25a is hardly conclusive. The external evidence has weighty witnesses for both reading I ( ) and reading IV ( ). Although reading IV without Hagar appears to be weightier

than reading I with Hagar, it still can be overturned by the internal evidence as to

its transcriptional and intrinsic probabilities.

3Transcriptional Probabilities

Transcriptional probabilities can readily explain some of the variant readings for

Gal 4,25. For example, the Byzantine reading II ( ) can be viewed

as a development of the Later Alexandrian reading I ( ) because

a scribe would have expected a clause beginning with Hagar and mentioning

Sinai to explain why Hagar was identified with the law promulgated from Sinai

in v. 24. The causal conjunction better integrates the explanation of v. 25a to

its context. The Byzantine reading II ( ) is also easier than the

reading IV ( ) because it makes the implied connection to Hagar more

explicit. In fact, the Byzantine reading II can even be considered a conflation of

readings I and IV. For these transcriptional reasons, it comes to little surprise the

Byzantine reading has proven to be stable once it was introduced in the transmission of the text. If either sub-variation unit seems less stable than the other,

it would appear to be the conjunction since there are some Byzantine witnesses

that read .

Now, the change from reading I to reading II (from to ) or from reading

IV to reading II (addition of ) is fairly simple to account for because either

change requires a single modification, either the substitution of the conjunction

or the addition of an implicit topic, respectively. Going between the two strongest readings, I ( ) and IV ( ), however, is more difficult.

Readings I and IV only differ by the inclusion or omission of the letters in

the context, [ ] , yet there is no apparent reason why a scribe

should add or omit these three letters accidentally. As a result, textual critics

offer a two-step transcriptional scenario to account for the change between these

two readings.

For this Hagar is Mount Sinai in Arabia (Galatians 4.25), in: The Old Testament in the New

Testament. FS J.L. North (JSNT.S 189), ed. S. Moyise, Sheffield 2000, 210219, esp. 214 n.8.

B. Wei, Textkritik der paulinische Briefe (TU 14.3), Leipzig 1896, 68, makes an argument similar

to Metzgers, but this was before the discovery and publication of P46.

70 Westcott and Hort, Introduction (see n. 14), App. 121.

Brought to you by | Uppsala University Library

Authenticated | 130.238.69.12

Download Date | 2/20/14 11:46 AM

94

Stephen C. Carlson

For example, Bruce Metzger, after adopting reading I ( ) on

external grounds, argues for the following transcriptional scenario: After

had replaced in some witnesses, the juxtaposition of led to the accidental omission sometimes of and sometimes of . A problem with

this scenario, however, is that Metzgers proposed intermediary form, reading II

( ), is both too late and too stable for it to give rise to reading IV

( ) in some of the earliest witnesses and then vanish without a trace

until much later.

As another example, Hans Dieter Betz has argued that the obscurity of

Hagar in reading I ( ) makes it the harder reading, tempting

scribes to improve it by deleting the name. This argument, however, misapplies

lectio difficilior. This criterion is for readings that are more difficult to the scribe,

not to the modern exegete. In fact, Betz later conceded that scribes would have

found the lack of Hagar difficult: The name Hagar itself can easily be interpreted as a later insertion, trying to help the argument by connecting more visibly

Sinai with Jerusalem. Indeed, if scribes had a problem with the inclusion of

Hagar, the Byzantine text-type would have seen more fluctuation in that subvariation unit than over the conjunction.

If there were any early attestation of reading III ( ), it would make

a good candidate for explaining the other readings on transcriptional grounds.

Like reading II ( ), it is a middle term between readings I (

) and IV ( ), in which the harshness of the asyndeton in

(III) would have induced scribes to introduce a connective particle, either by introducing to create (I), introducing to make

(II), or even by dropping the initial letter of to form

(IV). Only reading V ( ) would be difficult to account for as a direct modification of reading III. Because of its very late and very poor attestation,

however, reading III ( ) is best understood transcriptionally as result-

71 Metzger, Textual Commentary (see n. 17), 527. Also Sellin, Hagar und Sara (see n. 30), 7374

n.37; and much earlier, Wei, Textkritik (see n. 69), 68. Martyn, Galatians (see n. 14), 438, argues

the would have been replaced for being colorless.

72 Wei, Textkritik (see n. 69), 68, tries to avoid this problem by asserting that reading IV (

) is actually evidence for the early existence of reading II ( ): Wie alt

aber diese verfehlte Emendation ist, die nur noch vollstndig in KLP erhalten (doch vgl. schon

d e), erhellt daraus, dass in Folge derselben das nach p. hom. schon in CFG ausgefallen ist.

73 Betz, Galatians (see n. 13), 244245. The conjunction was presumably changed to clarify the

resulting text.

74 Betz, Galatians (see n. 13), 245.

Brought to you by | Uppsala University Library

Authenticated | 130.238.69.12

Download Date | 2/20/14 11:46 AM

For Sinai is a Mountain in Arabia

95

ing from the accidental deletion of the connective particle, probably the of

reading II ( ).

As for reading IV ( ), it does appear to be the earlier form of the text

from a transcriptional perspective. Unlike reading I ( ), reading

IVs lack of Hagar obscures the connection of the note in this context, so scribes

would have been inclined to make explicit the implied use of Hagar, based on

its placement immediately after in v. 24 and the presence of the

conjunction , which has three letters in common with .

A few critics have endorsed the reading V ( ) of P46 as the earliest reading. As with reading IV ( ), it is a more difficult reading for

scribes than readings I and II, both with an explicit , because the connection

to Hagar is only implicit. With respect to reading IV ( ), it might seem

initially plausible that the more colorless conjunction ought to be preferred

as transcriptionally prior, but the proposed originality of reading V ( )

would have to create a scribal coincidence out of the presence of the letters

in readings I ( ) and IV ( ). In order for reading V without the letters to be origin of readings I and IV, one must still account for

the origin of the letters in readings I and IV. It is more economical, on the

other hand, to suppose that the letters in readings I and IV shared a common

textual basis rather than originating from independent and coincidental scribal

innovations.

Like the external evidence, the transcriptional probabilities are also difficult

to decide, but on balance they appear to support, albeit slightly, the shorter reading IV ( ). We now turn to the final consideration: intrinsic probabilities.

4Intrinsic Probabilities

Intrinsic probabilities concern what the author would have most likely written,

paying particular attention to the context and to the authors style and thought.

In this case, the attested readings hardly have anything to commend themselves

as fitting the context of Pauls allegorical argument. For example, the longer reading with Hagar is redundant at best and contradictory at worst. In v. 24, Paul

75 Wright, Paul (see n. 48), 686 n.12; Lightfoot, Galatians (see n. 11), 193.

76 Kerkeslager, Jewish Pilgrimage (see n. 57), 182186; Muner, Hagar (see n. 57).

77 Kerkeslager, Jewish Pilgrimage (see n. 57), 182183.

78 Metzger, Text (see n. 16), 210211.

Brought to you by | Uppsala University Library

Authenticated | 130.238.69.12

Download Date | 2/20/14 11:46 AM

96

Stephen C. Carlson

had already identified Hagar with the Sinai covenant, but the longer reading of

v. 25a redefines Hagar with Mount Sinai itself. Moreover, the new geographic information of Mount Sinai being in Arabia is superfluous if Pauls intention was

to re-identify Hagar in his allegory. The shorter reading, without Hagar, on the

other hand, does convey the new information about the Arabian location without

disturbing the allegory by any redefinition of Hagars role in it.

Yet the shorter reading, locating Mount Sinai in Arabia, also has its problems.

One difficulty with the Hagar-less reading is the third clause of v. 25:

. This clause needs to pick up Hagar, not Sinai, as its subject, and so the back-reference to Hagar would have to skip over v. 25a all the way

to the end of v. 24: . Critics have also charged that the short reading is not original on intrinsic grounds, because it is merely a bald geographic

statement that does hardly anything to advance Pauls argument.

The note about Arabia is not merely semantically superfluous but structurally superfluous as well. As the following chart shows, both parts of Pauls explication of the allegory have the following parallel structure:

,

,

, .

,

In particular, elements A are syntactically related in a construction and

both present two female subjects in the nominative. Elements then predicate

the female subjects with a description relating to slavery ( ) or freedom (), both predications ending with a verb. Element uses the same

syntax to explain who the female subject is, Hagar and our mother

Sarah, respectively. Finally, element explicates certain qualities about these

79 See Kerkeslager, Jewish Pilgrimage (see n. 57), 184.

80 This consideration was decisive for Martyn, Galatians (see n. 14), 438, who concluded that

the presence of Hagar was necessary.

81 Especially Barrett, Allegory (see n. 52), 12. So also Schwemer, Himmlische Stadt (see n. 58),

200.

Brought to you by | Uppsala University Library

Authenticated | 130.238.69.12

Download Date | 2/20/14 11:46 AM

For Sinai is a Mountain in Arabia

97

females ending with a note about children (). In this tight structure, the

note about Arabia sticks out like a sore thumb. It has no corresponding element

on Sarahs side of the allegory.

These considerations raise the possibility that at least some or all of the v. 25a

parenthesis is a marginal note that was interpolated into the text of Galatians, as

some nineteenth-century textual critics have contended. As mentioned above,

Bentley found the mention of Hagar in the received text too difficult for the context

because it set up the anomalous, double identification of Mount Sinai with Hagar,

so he proposed to strike the sentence fragment from

the text with some adjustment in the syntax of the resulting sentence. To be

sure, Bentley later abandoned his conjecture, presumably because the variant

reading without Hagar avoided this particular problem. Even so, the shorter

reading that Bentley later adopted confirmed his earlier view that there was an

interpolation in the received text of v. 25a (

), but he changed his mind about what that interpolation included the

name Hagar.

Nevertheless, the shorter text, without Hagar, still did not stop scholars

from proposing interpolations in Gal 4,25a. For example, in 1834 Heinrich Schott

conjectured that the entire clause []

must have been a geographic gloss that crept into the text, because it impeded

and retarded Pauls argument. In favor of Schotts proposal, the resulting text,

without the clause, does indeed read smoothly without detriment to Pauls allegorical argument. Yet the great classical textual critic Paul Maas warns us that

82 I am thankful for the help of Jonas Holmstrand, who critiqued an earlier analysis of this

structure.

83 E.g., Schott, Galatas (see n. 12), 533; C. Holsten, Das Evangelium des Paulus 1, Berlin 1880,

171172; and S. A. Naber, , Mnemosyne NS 6 (1878) 85104, esp. 102.

84 Bentley, Epistola (see n. 1), 364365; see also nn. 910 above and accompanying text.

85 See nn. 11 and 47 above and accompanying text.

86 Schott, Galatas (see n. 12), 533: satis commode tamen abest, impediens quodammodo et

retardans argumentationem Paulinam. Indeed, Schott, not Bentley, should have deserved

the credit in the apparatus of the Nestle-Aland 27th edition for the conjecture, though Bentley

deserves recognition for identifying the passage as difficult. At any rate, the most recent 28th

edition of the Nestle-Aland text removed references to conjectures from its apparatus, so the

question of proper credit of this edition is now moot as far as the future incarnations of the

Nestle-Aland apparatus is concerned.

87 As another example, ONeill, Hagar (see n. 69), 216, adopted P46s singular reading of 4,25a

without Hagar to avoid the identification with Mount Sinai, but he then found himself exegetically compelled to add an explicit reference to Hagar in the subsequent clauses of v. 25 by adopting a singular reading from D* for the second clause and conjecturally emending the follow-

Brought to you by | Uppsala University Library

Authenticated | 130.238.69.12

Download Date | 2/20/14 11:46 AM

98

Stephen C. Carlson

interpolations are often very difficult to prove. In particular an interpolation

should not be suspected merely for being superfluous, since there is undoubtedly superfluous (or at least not demonstrably indispensable) matter in every

original. In the case of Gal 4,25 the parenthetical comment about Sinai being

a mountain in Arabia is undoubtedly superfluous: it does not contribute to the

allegorical argument and in fact complicates it. The Arabian note also spoils the

tight structure that Paul has constructed.

These are internal arguments, but there is also external evidence that v. 25a

once stood outside the main text. Allen Kerkeslager has called attention to the

overlooked textual variant following Gal 4,25a. Although Alexandrian and

Byzantine witnesses read after the geographic note, the Western witnesses read the feminine nominative participle instead. The closest feminine nominative antecedent for this particle is not in v. 25a at all, but at

the end of v. 24 the feminine Hagar. The longer reading of v. 25a with Hagar

would not supply the proper antecedent, because that instance of Hagar is actually neuter, taking the neuter article . On transcriptional grounds, it is difficult to see why a scribe would modify the in v. 25b to the participle

, when the entirety of the clause v. 25a stands between the particle

and its antecedent. Yet if v. 25a stood not in the main text but in the margin, the

connection between v. 24 and the Western variant in v. 25b is very smooth indeed:

, ,

ing to in the third clause of v. 25. As a result, ONeills text of v. 25 read as follows:

.

(219). Unfortunately for ONeills rather complicated and implausible proposal,

the resulting asyndeton between v. 25a and v. 25b is fairly harsh, and yet his text still does not

account for the presence of Arabia in v. 25a.

The proposal by G. Bouwman, Die Hagarund Sara-Perikope (Gal 4,2131): Exemplarische Interpretation zum Schriftbeweis bei Paulus, ANRW II 25.4 (1987) 31353155, esp. 3142, that the word

should be emended to read (the desert south of the Dead Sea) can be thought of

as an interpolation theory. In this case, the interpolation is a single iota. The only anomaly that

Bouwman pointed to in support of his emendation is the difference between 1,17 and 4,25 in the

use of the article before . Conversely, L. Baeck, The Faith of Paul, JJS 3 (1952) 93110, here

95 n.1 and D.S.A. Fries, Was meint Paulus mit in Gal 1,17?, ZNW 2 (1901), 150151, would

emend the in 1,17 to .

88 P. Maas, Textual Criticism, Oxford 1958, 14.

89 Maas, Textual Criticism (see n. 88), 1415.

90 Kerkeslager, Jewish Pilgrimage (see n. 57), 184185.

91 Since all the Western witnesses have some version of v. 25a, it is better to conclude that it

stood somewhere in their common ancestor, rather than they acquired the note independently

by contamination. A marginal note is the best place for this text to stand.

Brought to you by | Uppsala University Library

Authenticated | 130.238.69.12

Download Date | 2/20/14 11:46 AM

For Sinai is a Mountain in Arabia

99

. The attestation of the geographic note of v. 25a within all the

witnesses of Galatians means that this marginal note most likely had been present in the archetype of the textual transmission of Galatians, which was perhaps

the original edition of Pauls letter collection.

If v. 25a was a marginal note, intrinsic probabilities can still be used but the

question must be different: which form of the note would its author have likely

written? The function of the note, in all its forms, is to convey that Sinai was a

mountain in Arabia. Presumably, then, the author of the note believed that Mount

Sinai was in Arabia and wanted to use that information to explain the identification of Hagar with the Sinai covenant in v. 24 ( []

). This suggests that the note was to be connected to its context

either by a causal or by asyndeton. On this ground, the intrinsic probabilities

favor readings II ( ), III ( ), or IV (

). As for the presence of the word Hagar, the word order

among these readings is least problematic if was the subject of the clause

and belonged to predicate, so it is likely the note did not contain the confusing triple nominative . Furthermore, the main objection to the

Hagar-less reading that the third clause of v. 25,

, needs to pick up Hagar, not Sinai, as its subject does not apply to a marginal note, because there is no Sinai in the main text to interfere with

the reference to Hagar at the end of v. 24.

In other words, the marginal note probably did not have Hagar and so read

, with an indication that it should fall between the clauses of v. 24c and

of v. 25b. Some scribes added the note as-is, even in the Western manuscripts that

had changed to read as , but others may have misread

or modified the as and supplied a conjunction when incorporating

the note into the text.

If Gal 4,25a is a marginal note as the evidence suggests, was it written by Paul

or a later glossator? The previous arguments against the presence of the note in

the main text do not controvert the view that this could be Pauls own marginal

note. After all, its semantic and structural superfluousness is to be expected, even

for an authorial note. Despite the intriguing possibility that the archetypal letter

collection might have managed to preserve Pauls own notes on his epistles, there

92 Kerkeslager, Jewish Pilgrimage (see n. 57), 184185, considers the Western reading of the

participle to be original, which is plausible, but its smoothness suggests transcriptionally that it

was a scribal improvement. Kerkeslagers intrinsic argument for a falls short because,

even with his reading, Paul must have abandoned the construction.

Brought to you by | Uppsala University Library

Authenticated | 130.238.69.12

Download Date | 2/20/14 11:46 AM

100

Stephen C. Carlson

are two countervailing considerations. First, Michael W. Holmes has proposed

that some variant readings in P46 and other early witnesses are evidence of an

early commentary of Pauls letters in the form of marginal notes in an early second-century edition of the Pauline corpus. That Gal 4,24a appears to be another

marginal comment giving additional information about a step in the allegory fits

well with this proposed later context.

Second, although some scholars have called attention to Pauls only other

mention of Arabia in Gal 1,17, no one seems to have noticed that how Paul

thinks of Arabia in Gal 1 conflicts with its use in Gal 4. In Gal 1,1516, Paul told

the Galatians in defense of his apostolic ministry that God was pleased to reveal

his son in him so he would proclaim Christ among the Gentiles. As a result of this

experience, Paul did not visit Jerusalem to confer with the apostles before him,

but he immediately went to Arabia (v. 17). Thus, in Pauls mind, Arabia is coded

as Gentile territory. Yet in the allegory of Sarah and Hagar, Arabia does not function as Gentile territory. Quite the contrary according to the geographic note,

Arabia functions as the location of Mount Sinai where the law was promulgated.

Furthermore, in 1,17 Arabia is distinct from the present-day Jerusalem, while in

4,25 it is said to correspond (via the location of Mount Sinai) to the present-day

Jerusalem.

To be sure, Paul was not always the most consistent thinker. He mixed his

metaphors. Chapters 1 and 4 may well be so far removed from each other that it

is unreasonable to expect Pauls notion of Arabia in chapter 1 to continue to be

in force in chapter 4. But textual criticism is not about certainty but balancing

the probabilities. Without corroborating evidence of other marginalia that owe

their origin to Paul, it is reasonable to presume that marginal notes come from

later scribes, and so the supposition that this particular note is Pauline needs

a stronger rebuttal of this presumption than the observation that Paul was not

always consistent.

Therefore, the textual evidence indicates that the earliest form of the marginal note on the text of Gal 4,25 reads .

93 M.W. Holmes, The Text of P46: Evidence of the Earliest Commentary on Romans?, in: New

Testament Manuscripts: Their Text and Their World, ed. T. Nicklas, Leiden 2006, 189206.

94 E.g., U. Borse, Art. , EDNT 1, Grand Rapids, Mich. 1990, 149; M. Hengel / A.M. Schwemer, Paulus zwischen Damaskus und Antiochien: Die unbekannten Jahre des Apostels (WUNT

108), Tbingen, 1998, 191192; and Wright, Paul (see n. 48), 686.

95 Schwemer, Himmlische Stadt (see n. 58), 200, suggests that it was Pauls stay in Arabia that

provided the occasion for him to learn a local tradition about the Nabataean Hegra being the

location of Mount Sinai, though this does not attempt to address the conflict in Pauls conception of Arabia.

Brought to you by | Uppsala University Library

Authenticated | 130.238.69.12

Download Date | 2/20/14 11:46 AM

For Sinai is a Mountain in Arabia

101

Critical editions should reflect that wording. If Paul wrote the marginal note,

critical editions ought to show that fact, by putting the note in the margin where

its author intended it. If, however, Paul did not write the note, as the balance of

probabilities suggest, then it ought to be relegated to the apparatus with the notation Schott cj ex Bentley, giving proper credit both to the scholar who identified

the emendation and to the one who saw the difficulty. In either case, the note on

the text does not belong in the main text of a critical edition.

Brought to you by | Uppsala University Library

Authenticated | 130.238.69.12

Download Date | 2/20/14 11:46 AM

You might also like

- Das Älteste Evangelium - 050715Document343 pagesDas Älteste Evangelium - 050715Alma SlatkovicNo ratings yet

- Verborgene Schätze in Der BibelDocument29 pagesVerborgene Schätze in Der Bibelkareem_815226No ratings yet

- Strafanzeige MusterDocument2 pagesStrafanzeige MusterAlma SlatkovicNo ratings yet

- ... Außer Durch Beten Und Fasten, Roderick C. Meredith, 8 PDFDocument8 pages... Außer Durch Beten Und Fasten, Roderick C. Meredith, 8 PDFAlma SlatkovicNo ratings yet

- Unterrichtverlaufsplan Max CunhaDocument2 pagesUnterrichtverlaufsplan Max CunhaMax CunhaNo ratings yet

- Kurze Einführung in Die PsychologieDocument67 pagesKurze Einführung in Die PsychologieЛюдмилаNo ratings yet

- Latein Übungsklausur 15 (Latin Exam)Document1 pageLatein Übungsklausur 15 (Latin Exam)Miss-MuffetNo ratings yet

- Grammatik 1 (Al.)Document71 pagesGrammatik 1 (Al.)Sofia MermingiNo ratings yet

- Tiempos Aleman 2Document1 pageTiempos Aleman 2FLINVENo ratings yet

- Welcher Tag Ist Heute?: WortschatzDocument39 pagesWelcher Tag Ist Heute?: WortschatzGeorgiana StateNo ratings yet

- Sicher B1+ KBDocument2 pagesSicher B1+ KBДиана ГалееваNo ratings yet

- Lektion 1 Sicher C1.1., 27.5.2021Document16 pagesLektion 1 Sicher C1.1., 27.5.2021Alis MalovicNo ratings yet

- Wolfel-Monumentae Linguae Canariae PDFDocument941 pagesWolfel-Monumentae Linguae Canariae PDFHéctorahcorahNo ratings yet

- Englische, Wiemann - Unknown - Wir Hören, Was Wir Verstehen, Aber Wir Verstehen Nicht Immer, Was Wir Hören."Document99 pagesEnglische, Wiemann - Unknown - Wir Hören, Was Wir Verstehen, Aber Wir Verstehen Nicht Immer, Was Wir Hören."Gandhi HernándezNo ratings yet

- AdverbienDocument12 pagesAdverbienClaudio Pinheiro100% (1)

- Lösungen Buch 1 2. Juni 17Document87 pagesLösungen Buch 1 2. Juni 17Roxana DurdureanuNo ratings yet

- 2.3. Anrede: WWW - Deutschkurse-Passau - deDocument2 pages2.3. Anrede: WWW - Deutschkurse-Passau - deLệ TômNo ratings yet

- Publikationsformen Und InformationsmittelDocument9 pagesPublikationsformen Und Informationsmittelmspooh9290No ratings yet

- Versuchen Sie Es Mit Dem Ritter in Rostiger RüstungDocument4 pagesVersuchen Sie Es Mit Dem Ritter in Rostiger RüstungScribdTranslationsNo ratings yet

- Rhythm TrainingDocument19 pagesRhythm TrainingAthos80No ratings yet