Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Bilal 2002

Uploaded by

VLad2385Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Bilal 2002

Uploaded by

VLad2385Copyright:

Available Formats

Childrens Use of the Yahooligans! Web Search Engine.

III. Cognitive and Physical Behaviors on Fully SelfGenerated Search Tasks

Dania Bilal

School of Information Sciences, The University of Tennessee, 804 Volunteer Blvd., Knoxville, TN 37996.

E-mail: dania@utk.edu

This article presents the third part of a research project

that investigated the information-seeking behavior and

success of seventh-grade science children in using the

Yahooligans! Web search engine/directory. In parts 1

and 2, children performed fully assigned tasks to pursue

in the engine. In the present study, children generated

their tasks fully. Childrens information seeking was captured from the cognitive, physical, and affective perspectives using both quantitative and qualitative inquiry

methods. Their information-seeking behavior and success on the fully self-generated task was compared to

the behavior and success they exhibited in the two fully

assigned tasks. Children were more successful on the

fully self-generated task than the two fully assigned

tasks. Children preferred the fully self-generated task to

the two fully assigned tasks due to their ability to find the

information sought and satisfaction with search results

rather than the nature of the task in itself (i.e., selfgenerated aspect). Children were more successful when

they browsed than when they searched by keyword on

the three tasks. Yahooligans! design, especially its poor

keyword searching, contributed to the breakdowns children experienced. Implications for system design improvement and Web training are discussed.

Introduction

A recent survey by the U.S. Department of Education

shows that 98% of all public schools in the U.S. have

Internet access. The penetration of the Internet in schools

has increased from 78% in 1998 to 95% in 2000 (NUA,

2001). The number of children and young adults on-line has

grown from 8 million in 1997 to 25 million in 2000. NUA

estimates that by 2005 more children will go on-line at

school than at home.

Received March 27, 2002; revised May 17, 2002; accepted May 17,

2002

2002 Wiley Periodicals, Inc. Published online 19 September 2002 in

Wiley InterScience (www.interscience.wiley.com). DOI: 10.1002/asi.10145

The Web is an information retrieval system (IR) that

differs considerably from its conventional on-line counterparts (i.e., CD-ROM, OPAC). First, it is a vast, dynamic,

and heterogeneous hypertext system that creates cognitive

overload and disorientation on users. Second, its content is

uncontrolled and, therefore, the quality of information cannot be guaranteed. Third, it lacks indexing conventions,

thereby making information retrieval often imprecise

(Schacter, Chung, & Dorr, 1998). Fourth, a sites viability

may require it to have advertising potential, which is a

function of the number of visitors it attracts . . . Webmasters

[may] pad their sites with commonly used but inapplicable

search terms in the hope of increasing the number of visitors

the site attracts . . . This can produce hits that have nothing

to do with ones search topic (Broch, 2000, p. 5).

Research has shown that children and adults often experience difficulty finding information on the Web (Bilal,

1998, 2000, 2001; Bilal & Kirby, 2002; Jansen, Spink, &

Saracevic, 2000; Large & Beheshti, 2000; Large, Beheshti,

& Moukad, 1999; Nahl, 1997; Schacter et al., 1998; Wang,

Hawk, & Tenopir, 2000). The infusion of the Web in public

schools, coupled with its unstructured and uncontrolled

nature raises questions about childrens information seeking

and success in finding information. The fact that childrens

information needs vary from those of adults (Bilal & Kirby,

2002) and that their cognitive ability, terminology, problem

solving skills, and mechanical skills (e.g., typing) are not as

developed as those of adults (Bjorklund, 2000; Piaget &

Inhelder, 1969; Siegler, 1998) make them a special user

group to study. Studies have shown that even when children

use a search engine that is specifically designed for their age

level, they encounter difficulty, including applying correct

search syntax and finding relevant results (Bilal, 2001;

Bilal, 2000; Large & Beheshti, 2000; Bilal, 1998). The tasks

that children perform may also influence their information

seeking behavior and success in finding information on the

Web. Typically, in public schools children often perform

search tasks that are imposed (i.e., assigned), and that may

JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN SOCIETY FOR INFORMATION SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY, 53(13):1170 1183, 2002

be of little or no interest to them (Gross, 1997). When

children carry out tasks that do not require use of their

content knowledge creatively, they are less likely to succeed

(Hirsh, 1999) and recover from system breakdowns (Solomon, 1994). Oliver and Oliver (1997) maintains that to

lead to higher levels of knowledge acquisition, learning, and

engagement, tasks given to children should be based on

contextual purposes. Small (1999) notes that the type of

tasks children are given should stimulate and encourage

intellectual curiosity, information seeking, and exploration

behaviors. Garland (1995) supports these views, and contends that when children select their research topics, they

develop a sense of control and tend to be more positive

about embarking on a research project than if they had used

an assigned topic. In her study of a group of middle school

students, Pitts (1995) found that one of the criteria the

students employed in selecting topics for a class project was

interest in the subject matter. Thus, one may infer that when

children generate their own topics, they may be more motivated, challenged, engaged, and successful than when they

pursue topics that are imposed or assigned.

Although we have knowledge about the influence assigned closed- and open-ended tasks have on childrens

information-seeking behavior and success (Borgman et al.,

1995; Hirsh, 1997; Large et al., 1994; Marchionini, 1989;

Schacter, Chung, & Dorr, 1998), we have little knowledge

about the effect that fully self-generated tasks have on

childrens success and information seeking. This study is an

initial attempt to fill this gap in the literature.

Taxonomy of Tasks

The literature does not clearly distinguish between fully

assigned, semiassigned, and fully self-generated. A task is

an essential factor in the information seeking process. Research has shown that the type of task a user is given

influences the users information seeking, information use,

and success (Bilal, 2000, 2001; Borgman et al., 1995; Bystrom & Jarvelin, 1995; Dimitrof & Wolfram, 1995; Hirsh,

1997; Marchionini, 1989, 1995; Qui, 1994; Schacter,

Chung, & Dorr, 1998; Solomon, 1993, 1994; Vakkari,

1999). As Figure 1 shows, tasks vary by type (i.e., openended vs. closed), nature (complex vs. simple), and the way

they are administered (i.e., fully assigned, semiassigned,

fully self-generated). Typically, open-ended tasks (also

known as research oriented) are complex in nature. They

have ill-structured problems, where the information required for accomplishment cannot be determined in advance

(Bystrom & Jarvelin, 1995; Vakkari, 1999). Typically,

closed tasks (also known as fact finding) are simple, well

defined, and have structured problems. They can be routine

information processing tasks with elements that are predetermined (the user knows them). The complexity or simplicity of a task may depend on its formulation and characteristics (e.g., cognitive and skill requirements, number of

existing facets or elements).

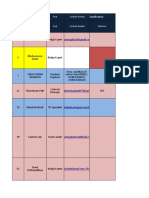

FIG. 1.

Taxonomy of tasks.

Closed- and open-ended tasks can be administered in

three ways: fully assigned, semiassigned, or fully self-generated. Fully assigned tasks are those that have both the

main topic and aspects of the topic imposed on the user.

Semiassigned tasks are those that have only the main topic

imposed on the user, and the user can choose an aspect of

the topic that interests him or her to pursue. Fully selfgenerated tasks are those that have both the main topic and

an aspect of the topic generated by user. Based on the

taxonomy of tasks shown in Figure 1, four possible outcomes for tasks can be driven:

(1) A task may be open-ended, complex; fully assigned,

semiassigned, or fully self-generated.

(2) A task may be closed, simple; fully assigned, semiassigned, or fully self-generated.

(3) A task may be open-ended, simple; fully assigned,

semi-assigned, or fully self-generated.

(4) A task may be closed, complex; fully assigned, semiassigned, or fully self-generated.

In the present study, children were asked to generate

their own tasks fully. Their information seeking behavior

and success on these tasks were compared to the behavior

and success they demonstrated on the two fully assigned

tasks (one research oriented and one fact finding) they had

performed in the two previous studies (Bilal, 2000, 2001).

Related Literature

Three bodies of literature relevant to this study were

reviewed: childrens use of CD-ROM databases, of on-line

catalogs (OPACs), and of the World Wide Web (Web).

Childrens Use of CD-ROM Databases

Large, Beheshti, and Breuleux (1998) examined the use

of three multimedia CD-ROM encyclopedias by 53 middle

school students for a class-related project about Middle

Ages. The students were to deliver a written assignment on

people in the Middle Ages, make an oral presentation, and

JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN SOCIETY FOR INFORMATION SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGYNovember 2002

1171

construct a three-dimensional model of a manorial system.

Students were given a semiassigned task, that is, a list of

nine people to choose from for the written assignment and

a list of nine topics from which to select three for the oral

presentation. Although the students demonstrated confidence in operating the various encyclopedias, they encountered more problems with Exploring Castles than with Encarta or Castle Explorer due to its inadequate design. Overall, students had difficulty constructing effective queries and

with mastering the retrieval strategies of the encyclopedias.

This study did not examine the impact the topics that

children selected had on their success and information seeking behavior.

In a prior study, Large et al. (1994) compared middle

school students use of print and CD-ROM versions of

Comptons Multimedia Encyclopedia. Each student had to

answer four assigned questions that varied in complexity.

Complexity was defined by the number of search terms the

queries contained, from one word to four. Query complexity

affected retrieval time in both sources. Although in the 1998

study the students were able to choose aspects of an assigned topic to pursue (semiassigned task), the students in

the 1994 study performed fully assigned tasks. It is unclear

how complexity and use of fully assigned rather than semiassigned tasks influenced childrens success and information seeking behavior.

Using two assigned search tasks, one closed and one

open ended, Marchionini (1989) examined the searching

behavior of third, fourth, and sixth graders in utilizing a

full-text CD-ROM encyclopedia. He observed that older

children were more successful on both tasks than younger

ones and that the nature of the task (closed vs. open-ended)

did influence the students information-seeking strategies

and success rates in finding the desired information. Overall, children were more successful on the open task than on

the closed task.

Childrens Use of On-line Catalogs (OPACs)

Borgman et al. (1995) conducted a series of studies with

an experimental on-line catalog called the Science Library

Catalog (SLC), a browsing system that was designed to

facilitate childrens information seeking. The authors examined the success and searching behavior of 32 children, aged

9 through 12, as they used four versions of SLC and two

keyword OPACs, Orion and LePac. In Experiments 13, the

researchers assigned the topics to the children to search in

the OPACs from a list of curriculum-related science topics

compiled by the teacher. In Experiment 4, each child selected one topic from a science set and one other topic from

a technology set. Children were able to find some of the

topics more easily in the SLC than on the OPACs, particularly when the topics were open ended or difficult to spell.

In the two open-ended topics that the children performed,

they did better in the SLC than in the OPAC. The design of

the SLC facilitated childrens information seeking in finding

1172

the desired information on both the assigned and semiassigned tasks.

In a later study of the SLC, Hirsh (1997) examined the

impact of task complexity on childrens information retrieval. Sixty-four fifth grade children, ages 10 11, participated in the study and performed eight assigned tasks that

varied in complexity. Contrary to Marchioninis findings

(1989), Hirsh observed that science domain knowledge

rather than the type of the task (open ended vs. simple)

significantly influenced childrens success rates.

Solomon (1993) collected data over a school year to

examine the search strategies and type of information seeking breakdowns children in grades one through six experienced. Data was collected during students OPAC orientation sessions, planned research, and curriculum-related use.

Childrens cognitive developmental abilities influenced the

search moves they made and that inadequate design of the

OPAC contributed to many of the breakdowns the children

encountered. It is unclear, however, whether the nature of

the tasks influenced their success or contributed to the

breakdowns they had experienced.

Childrens Use of the Web

Studies of childrens use of the Web have recently

emerged. Bilal (1998, 2000, 2001) conducted studies of

childrens information-seeking behavior in using the Yahooligans! Web search engine/directory to find information

for fully assigned research-oriented and fact-finding tasks.

The key findings of these studies are below.

Childrens information seeking and success on fully assigned

research-oriented tasks. Bilal (2001) investigated the success and information-seeking behavior of 17 seventh-grade

science children in using Yahooligans! to locate relevant

information for an assigned research task about the depletion of the ozone layer. The author captured childrens

Web moves using the Lotus ScreenCam software package.

Childrens success was measured in three ways. They were

judged to be fully successful if they printed and submitted

all relevant pages with a short text (12 pages). They were

considered partially successful if they printed and submitted

selected relevant pages that discussed the topic. They were

deemed unsuccessful if they printed and submitted irrelevant information or if they did not submit any information.

Two middle-school science teachers and one expert in environmental science evaluated childrens search results and

judged their success. Results showed that 69% of the children partially succeeded and 31% failed. Regardless of

success, however, children seemed to seek specific answers

to the task rather than develop understanding of the information found. Evidence of this approach was seen in their

search results that contained fragments of sentences highlighted as answers. Children had more difficulty with the

research task than with the fact-finding task they performed

in the previous study (Bilal, 2000). This finding is not

JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN SOCIETY FOR INFORMATION SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGYNovember 2002

surprising, because the research task was more complex,

contained multiple facets, and required that children construct meaning from the relevant information found. Children possessed inadequate knowledge of the informationseeking process.

Childrens physical behavior varied by success levels.

Partially successful children backtracked less often than

unsuccessful ones (mean ! 4.7 vs. 9.25, respectively), made

fewer Web moves (mean ! 34 vs. 56, respectively), and

took half the time to complete the task (mean ! 8 minutes

vs. 16 minutes, respectively). These differences appeared to

be influenced by the difficulty that unsuccessful children

experienced in finding relevant information. The inadequate

design of Yahooligans!, especially its keyword searching

was a major problem. Children expressed their information

needs and made recommendations for improving the engines interface design.

In a pilot study of middle school students use of Yahooligans! to locate information for a fully assigned research task about diet, Bilal (1998) found that children

were unsuccessful in finding the relevant information they

needed. Here also, children encountered difficulty in using

the engine and in navigating its space. Again, Yahooligans!

inadequate design surfaced as a problem and influenced

childrens information seeking and success.

Childrens information seeking and success on fully assigned

fact-based tasks. Bilal (2000) examined childrens information seeking and success as they used Yahooligans! to

locate the correct answer for an assigned fact-based task

about the age of alligators in the wild and in captivity.

Twenty-two children from three seventh-grade science

classes taught by one teacher participated in the study.

Childrens success rates in finding the correct answer to the

task was judged by extracting the correct facts from the

relevant home page that contained the answer. Both quantitative and qualitative methods were employed to collect

the data. Childrens Web moves were captured using the

Lotus ScreenCam software package. Their prior knowledge

about the Web and Yahooligans! was gathered through a

questionnaire that was administered before using the engine. Their affective states were collected via individual exit

interviews that took place at the end of the research experiment. The Web Traversal Measure the author employed

quantified the moves children made and provided a weighted score that measured effectiveness, efficiency, and quality in using Yahooligans! Findings reveal that 50% of the

children found the correct answer to the task. Childrens

cognitive behavior reflected an understanding of the task,

term relationships, and placement of topics within appropriate subject hierarchies. Childrens information-seeking

behavior varied by success levels. Successful children employed incorrect search syntax less often, looped searches,

and hyperlinks (reactivated previous searches and relaunched previously visited links) less frequently, took less

time to complete the task (mean ! 11.89 vs. 19.69 minutes),

and appeared to be more engaged and focused in completing

it. The Web Traversal Measure showed that successful

children were more effective than unsuccessful ones

(31.14% vs. 12.42%). These scores mean that successful

children put nearly 70% of their efforts to locate the target

hyperlink, whereas unsuccessful ones devoted nearly 88%

to that end. Successful children were relatively more efficient that unsuccessful ones (26.28% vs. 22.14%), and had

a higher score of quality moves (32.14% vs. 28.85%, respectively). Most children (85%) were highly motivated to

use the Web, but were confused and frustrated mainly due

to lack of matches in Yahooligans! Childrens motivation,

self-confidence, and challenge in using the engine surfaced

as main factors that influenced their patience and persistence in completing the task. No child quit searching before

the allotted time given.

A recent study found that not only children but also

adults experience difficulty in using Yahooligans! Bilal &

Kirby (2002) compared childrens and graduate students

information-seeking behavior and success in using the engine to find the correct answer for a fully assigned factfinding task. Childrens information needs varied from

those of the graduate students. Both student groups experienced cognitive difficulty in using the engine, employed

incorrect search syntax, and were frustrated during the

search process. Children and graduate students made recommendations for improving Yahooligans! design to support their information seeking and information needs.

Other Web research. Large and Beheshti (2000) interviewed 50 middle school students after they used Infoseek

and Alta Vista search engines to find information about a

semiassigned task dealing with Winter Olympics. The

teacher allowed the students to pursue their chosen sport

from a list of 14 activities. Overall, children had difficulty

finding relevant information due to information overload

and were dissatisfied with most of the information they

found. Children liked the speed in using the Web, but found

it harder to use than print sources. The authors did not

examine whether the topics children pursued influenced

their success, cognitive behavior, or affective states in using

these sources.

Hirsh (1999) explored the relevance criteria and search

strategies of 10 fifth graders in using an on-line catalog, a

CD-ROM magazine index, the Web, and a CD-ROM encyclopedia to locate information for a semiassigned task. The

teacher assigned students to write a research paper about

any sports figure they wanted. Children exhibited little

concern for the authority of textual and graphical information they found and spent most of their time finding pictures

and relied heavily on the Web for their research. As before,

the study revealed that children had little concern for evaluating the quality of Web content (Watson, 1998), rarely

examined the pages retrieved (Bilal, 1998), and that few

questioned the accuracy of the information they find (Kafai

& Bates, 1997). Hirsh (1999) observed that children were

JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN SOCIETY FOR INFORMATION SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGYNovember 2002

1173

motivated in seeking information about the specific topics

that interested them.

Schacter, Chung, & Dorr (1998) examined the searching

behaviors of fifth and sixth graders in using the Web for two

fully assigned tasks: one closed and one open ended. The

nature of the task influenced childrens success in finding

the desired information as well as their information-seeking

strategies. Children were more successful on the open task

than the closed one, and they made more analytic searches

on the closed as opposed to the open task.

Using a semiassigned research task, Wallace and Kupperman (1997) observed a group of sixth graders as they

used the Web to find information for a class-related project

about ecology. Despite the fact that children chose specific

aspects of ecology that interested them, they were not successful in locating the desired information. Children possessed an inadequate level of research skills, had naive Web

navigational skills, and approached the task by seeking

specific answers.

In sum, the literature reveals that regardless of the information retrieval system used, most tasks that were given to

children were either fully assigned or semiassigned. This

finding is not surprising, however, because teachers must

assign tasks that are class-related. In addition, the issue of

imposed queries did not surface until 1997 when Melissa

Gross studied their prevalence in school libraries. How

successful are children in finding information in Yahooligans! for fully self-generated tasks? Does childrens information-seeking behavior in finding information in Yahooligans! vary by the way tasks are administered (i.e., fully

self-generated vs. fully assigned)?

Research Questions

This study examined the information-seeking behavior

and success of seventh graders in using Yahooligans! to find

information for fully self-generated tasks. It investigated

childrens behavior from the cognitive and physical perspectives. The cognitive aspect of information seeking pertains to thoughts (the cognitive domain) and the physical

aspect to actions (the sensorimotor domain). In this study,

the cognitive behavior was explored in terms of searching

and browsing, and the physical behavior was examined in

terms of looping searches and hyperlinks (i.e., reactivating

previously executed searches and clicking on previously

visited sites/hyperlinks), total Web moves made, time taken

to complete the task, and exploratory moves (e.g., use of

Netscape Help).

In interacting with an information retrieval system, such

as Yahooligans!, it becomes important to learn the underlying thoughts and cognitive processes of the user (Ingwersen, 1996), and how these thoughts interact with their

actions and affective states (Dervin, 1983; Kuhlthau, 1993).

By examining childrens thoughts, actions, and preferences,

one can obtain a holistic view of their information-seeking

behavior.

The following questions guided the present study:

1174

(1) How successful are children in finding information for

their fully self-generated tasks, and how does this success compare to their success on the two assigned tasks

(fact-finding and research-oriented) that they had performed in the previous studies?

(2) What cognitive behavior do children demonstrate in

using Yahooligans! to find information for their fully

self-generated tasks, and does this behavior vary from

the behaviors they exhibited on the two assigned tasks

(fact finding and research oriented) that they had performed in the previous studies?

(3) What physical behavior do children demonstrate in using Yahooligans! to find information for their fully

self-generated tasks, and does this behavior vary from

the behaviors they exhibited on the two assigned tasks

(fact-finding and research-oriented) that they had performed in the previous studies?

(4) What tasks (fully self-generated vs. fully assigned) do

children prefer, and why?

Method

This study employed both quantitative and qualitative

inquiry methods. Through the quantitative method, data

about childrens Web moves were captured using the Lotus

ScreenCam software package. Through the qualitative

method, childrens task generation and data about task preference were captured using individual interviews that took

place at the conclusion of the research experiment.

The Setting

The study took place at a Middle School (named Middle

School for confidentiality purposes) located in East Tennessee. At the time of the research experiment, the School

library had two computer stations with an Internet connection. For purposes of the study, three computers were added,

networked, and connected to the Internet to accommodate

use of five computers simultaneously. Lotus ScreenCam

version 2.0 was installed on each computer to capture childrens Web activities. Software and hardware were pretested to ensure proper operation. Yahooligans! was set up

as the default home page in the Netscape browser.

Population and Sample

The population for this study consisted of students in

three science classes (90 students) taught by one science

teacher. Due to the Schools Internet Use Policy, childrens

parental consent to use the Internet was sought. Out of 90

invitations the teacher sent to the parents, 30 consent forms

were received. Of these, 25 children were willing to take

part in this project. Three were involved in pilot testing,

leaving 22 children who participated in the present study.

The children who participated in this study were the same as

those who took part in the previous two studies (Bilal, 2000,

2001).

JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN SOCIETY FOR INFORMATION SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGYNovember 2002

Childrens Fully Self-Generated Tasks

Children were asked to select topics of interest to search

in Yahooligans! They were instructed to transcribe the

topics on the work sheet given to them. The researcher and

the school librarian examined the topic statements that

children generated and found that they were open ended and

stated in a broad sense. Examples: I want information about

Ebola virus; What can dogs do to help out other people; I

want information about psychology. Three children transcribed two initial topics of interest to pursue; four modified

their topics during searching as they were allowed to do so

if they did not find information of interest or if they changed

their mind about their initial topics. Two children had two

different subject matters in their topic statements (e.g., I

want to find information on baseball and gymnastics; I want

information about acting and skating). After mediation, five

of the topics that children generated and were open ended

became fact finding and more focused. The child who

transcribed the topic What can dogs do to help out other

people, for example, identified his/her main interest as the

kind of birds springer spaniels flush out from, which is, in

fact, a new topic rather than an aspect of the initial topic.

Five children (33%) were unable to choose specific aspects

of their topics to pursue during mediation. They mentioned

that they would do so based on what they found in Yahooligans! during searching. Appendix 1 shows a sample of the

topics that children generated before mediation.

Success Measure

Both the researcher and a research assistant from the

School of Information Sciences judged childrens success in

finding the information sought. Each search result (printout)

that a child submitted was reviewed vis-a`-vis the topic(s)

that he/she pursued to judge success. Children were judged

to be successful if they found any relevant information

pertaining to their topics. They were judged to be unsuccessful if they did not find any information about the topics

or if they submitted irrelevant information.

Instruments

The researcher developed and used a work sheet to be

used by children to transcribe their fully self-generated

topics. The work sheet contained instructions about how to

proceed in using Yahooligans! after choosing the topics.

The work sheets were placed in front of the children at the

their computer stations throughout the search process. The

researcher utilized an additional sheet that contained two

interview questions, which were: (1) out of the three search

tasks that you did in Yahooligans!, what task did you like or

prefer the most?, and (2) for what reasons did you prefer

that task? Children were interviewed individually by the

researcher at the conclusion of the research experiment.

Procedure

The research experiment began in April 1998. Both the

science teacher and the researcher described the nature of

the project to the children. As they volunteered to participate, children were escorted five at a time to the School

library and instructed to sign a consent form. After the task

was explained to them, they were asked to transcribe the

topic they would like to pursue in Yahooligans! on the work

sheet that was given to them.

Children were instructed to (a) use the work sheet to

transcribe their topics; (b) perform the task in Yahooligans!

only, (c) limit search time to 45 minutes, (d) highlight the

information that met their need using the computer mouse,

(e) print the information found, (f) highlight the relevant

information on the printout using a marker, and (g) announce the completion of the task to the researcher and/or

the school librarian. When a child did not locate information

on a topic, the child was allowed to modify the topic.

Children were encouraged to ask questions as needed. When

technical problems occurred, children were given additional

time to complete their tasks. Upon completion, each childs

Web session was saved on the local computer used. All Web

sessions were transferred electronically to the researchers

computer station. Each session was replayed, analyzed, and

transcribed by both the researcher and a trained research

assistant.

Limitations of the Study

This study involved 22 children aged 12 and 13 years

old. However, the results of this study are based on 15

usable Web sessions that replayed fully. The children who

participated in this study were selected from three seventhgrade science classes in one Middle School located in East

Tennessee; therefore, they may not represent all middle

school students in Tennessee, nor may they represent the

general population of seventh-grade science students.

The fact that the data presented in this study were collected in 1998, the data reflect the participants cognitive

and physical behaviors in using the Yahooligans! search

engine at that time. It is possible that these participants

behaviors have changed since then.

At the time of this study, Yahooligans! was the only Web

search engine designed for children ages 712. Despite this

fact, use of only one search engine to examine childrens

information-seeking behavior may not represent an in depth

view of childrens behavior in using Web search engines.

Another limitation concerns lack of concurrent verbalization during use of Yahooligans! The fact that exit interviews took place at the end of the research experiment

rather than immediately after children completed their tasks

may impact the reliability of the responses due to recall.

Results

The results of this study are reported within the context

of the four research questions posed. Due to data loss, the

results are based on 15 usable Web sessions that replayed

fully. Due to the small sample size (15), descriptive statistics were employed to describe trends in the data. The

JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN SOCIETY FOR INFORMATION SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGYNovember 2002

1175

children who participated in this study were the same as

those who took part in the previous two studies.

Research question 1. How successful are children in

finding information for their fully self-generated tasks,

and how does this success compare to the success they

had on the two fully assigned tasks (research-oriented

and fact-finding) that they had performed in the previous studies?

Eleven children (73%) were successful in finding the

information they sought on their fully self-generated

tasks. Twenty-seven percent were unsuccessful either

because they did not find any information of interest or

that they were undecided as to the information they were

seeking. One child who was unsuccessful, for example,

submitted the wrong answer to the topic selected (i.e., the

name of the head coach of the Atlanta Braves). One child

who sought information about veterinarians, for example, misspelled the term repeatedly. The child tried the

related term horses, but was still unsuccessful. Similarly, the child who sought information about psychology as a career misspelled psychology and psychologists. Another child who looked for information about

art, was undecided about which aspect of the topic to

pursue after viewing the retrieved results. The child who

looked for information about games browsed related

sites, but did not select any information. Another child

who searched for information about poetry and specifically the poetry of Walt Whitman was uncertain as to

the poem to use. Similarly, the child who sought information about Spice Girls was undecided as to the

information to obtain about the group. It seems that these

children did not possess a clear focus about their information need, despite the fact that the researcher and

school librarian assisted them in clarifying their specific

topics before using Yahooligans! It is noteworthy that

there were cases when children searched under broad

terms they extracted from their initial topics rather than

using the more specific terms from the mediated topics

(e.g., games instead of video games).

Overall, children were more successful on the fully selfgenerated task than on the two fully assigned tasks they had

performed in the previous studies. On this task, 73% succeeded in finding the information sought for the fully selfgenerated task, compared to 69% who partially succeeded

on the research-oriented task and 50% who fully succeeded

on the fact-finding task.

Research question 2. What cognitive behavior do children demonstrate in using Yahooligans! to find information for their fully self-generated tasks, and does this

behavior vary from the behaviors they exhibited on the

two fully assigned tasks (research-oriented and factfinding) that they had performed in the previous studies?

Childrens cognitive behavior was examined in relation

to searching and browsing.

1176

Searching

Thirteen out of 15 children (87%) began their initial

moves by performing keyword searches using single and

two terms in their search statements. Most of these searches

included broad terms that children extracted from their

initial rather than mediated topics. The child who selected

the topic about large oil reserves, for example, entered

oil, in the initial move and oil reserve in the subsequent

move. Another child who needed information about the

name of the coach of the Atlanta Braves typed baseball

instead of Atlanta Braves.

Two children committed misspelling errors, one misspelled veterinarians as veternarians and another misspelled psychology as phsychology, and psychologists as physychologits. The first child modified the

search by using synonyms (e.g., pet doctors, dog doctors),

but found no matches. The child switched to the new topic

horses. Apparently, the child was unaware of the error

he/she committed. The fact that Yahooligans! did not have

a spell-checking technique to alert the child about the error

contributed to the breakdown the child experienced. Although the child found three categories and 33 sites under

horses, the child did not select any information to view.

The second child failed in his/her quest and transcribed on

his/her sheet that he/she did not find any information about

the topic.

Childrens search moves varied by task. As shown in

Table 1, they performed more searches on the fully selfgenerated task (mean ! 5.05) than the research-oriented

task (mean ! 3.07). The number of searches on the former

is lower than that on the fact-based task (mean ! 6.7).

Thirteen percent submitted natural language on the fully

self-generated task, whereas 8% performed this type of

searching on the research-oriented task and 35% did so on

the fact-based task. Most searches on the fully self-generated tasks had two concrete concepts, whereas most

searches on both the research-oriented and fact-based tasks

contained single concrete concepts. No child used Boolean

operators, indicating childrens unfamiliarity with this type

of searching.

Search moves also varied by success levels on the three

tasks (Fig. 2). Successful children made fewer keyword

searches on the three tasks. Their mean score of search

moves was 5.5 on the fully self-generated task, 2.4 on the

research-oriented task, and 3.49 on the fact-based task.

Unsuccessful childrens score on these tasks had a mean of

4.78, 8, and 10, respectively.

Browsing

Children browsed much more than searched by keyword

to find information about their topics. They activated 117

hyperlinks, of which 93 were appropriate to the information

sought (appropriateness ratio ! 79%). The number of hyperlinks they browsed varied by success levels (Fig. 2).

Successful children activated 68 hyperlinks (mean ! 7.5),

JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN SOCIETY FOR INFORMATION SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGYNovember 2002

TABLE 1.

Childrens Web activities on the three tasks.

Variable

Fully self-generated task

(n ! 15)

Research-oriented task

(n ! 13)

Fact-based task

(n ! 14)

73%

69%

50%

M ! 5.05a

13%

13%

M ! 12.26

M ! 1.93

M ! 7.4

M ! 14.35 minutes

33%

M ! 78

47%

M ! 3.07a

8%

2%

M ! 4.15

M ! 1.54

M ! 6.07

M ! 10.42 minutes

23%

M ! 41

20%

M ! 6.7a

35%

2%

M ! 8.4

M ! 5.1

M ! 12.2

M ! 15.78 minutes

64%

M ! 49

20%

Success

Search moves

Keyword

Natural language

Misspelling

Browsing moves

Looping moves

Backtracking

Time

Exploratory moves

Web moves

Task preference

a

M!Mean score.

whereas unsuccessful ones activated 49 hyperlinks (mean

! 8.1). Regardless of success, however, most children

visited sites that were irrelevant to the information need.

The child who wanted information about summer Olympic

games basketball, for example, activated five links relating to rock music. The child who needed the name of the

coach of the Atlanta Braves activated three links, one about

chess, one about games, and another about computer

games. It is possible that these children wanted to explore

FIG. 2.

topics of interest other than those they were pursuing. A few

others did not wait for the results to load after activating the

hyperlinks; and they switched immediately to keyword

searching. One child, for example, clicked on the category

Smith, Will, then on the site Will Smith, and performed

a keyword search under Will Smith before the results

loaded.

Childrens browse moves varied by task (Table 1). They

browsed more on the fully self-generated task (mean

Childrens Web activities on the three tasks by success.

JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN SOCIETY FOR INFORMATION SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGYNovember 2002

1177

! 12.26) than both the research-oriented task (mean

! 4.15) and the fact-based task (mean ! 8.4). As stated

earlier, 20% of the children pursued two topics each, 26%

modified their topics during searching, and 33% searched

under their initial broad topics because they were undecided

about the specific aspects to pursue. The number of topics

pursued and their variety influenced the number of browsing

moves that children made on the fully self-generated task.

Browsing varied by success levels on the three tasks

(Fig. 2). Successful children activated nearly the same number of hyperlinks (mean ! 7.5 hyperlinks) on the fully

self-generated task as did unsuccessful ones (mean ! 8.1).

On the research task, however, partially successful children

activated a much lower number of hyperlinks (mean

! 3.28) than did unsuccessful ones (mean ! 8.75). Similarly, successful children browsed fewer hyperlinks (mean

! 7.58) on the fact-based task than did unsuccessful ones

(mean ! 9.29). It seems that the more difficulty unsuccessful children experienced in finding the information sought,

the more they visited hyperlinks.

Research question 3. What physical behavior do children demonstrate in using Yahooligans! to find information for their fully self-generated tasks, and does this

behavior vary from the behaviors they exhibited on the

two fully assigned tasks (research-oriented and factfinding) that they had performed in the previous studies?

The physical behavior was observed in terms of the

actions children made other than searching and browsing.

This included use of Netscape Back command (i.e., backtracking), looping (i.e., reactivating previously executed

searches and clicking on previously visited sites/hyperlinks), total number of Web moves made, time taken to

complete the tasks, and exploratory moves (e.g., use of

Netscape Help).

Backtracking

Backtracking allows the viewing of previously retrieved

Web pages in a linear mode. Overall, children backtracked

111 times (mean ! 7.4) while completing their fully selfgenerated tasks. The number of backtracks varied by success levels (Fig. 2). Successful children backtracked less

often on the fully self-generated tasks (mean ! 7) than

unsuccessful ones (mean ! 8). Children clicked on the Back

command but did not view most of the pages they had

retrieved. One child, for example, clicked on Back repeatedly, did not wait for the results to load, clicked on Forward

and immediately clicked on Back again. The child initiated

a new keyword search under Green Bay, although the

pages he/she had previously retrieved contained information

on this topic. Most children backtracked to loop hyperlinks.

The farther they were from these hyperlinks, the more often

they backtracked. Had these children recognized shortcuts to reactivate these hyperlinks, they would have backtracked less often and completed their tasks more efficiently.

1178

Backtracking varied by task (Table 1). Children backtracked a little more on the fully self-generated task than

they did on the research-oriented task (mean ! 7.4 vs. 6.07,

respectively), but did so much more on the fact-finding task

(mean ! 12.2). Backtracking also varied by success levels

on the three tasks (Fig. 2). Successful children backtracked

less often on fully self-generated task (mean ! 7), the

research-oriented task (mean ! 4.7) and the fact-finding

task (mean ! 5.8) than did unsuccessful children (means of

8, 9.25, and 6.4, respectively).

Although childrens frequent backtracking may be typical of user behavior on the Web (Tauscher & Greenberg,

1997), activation of shortcuts, such as the History list and

Go list may be more efficient. Lack of use of these shortcuts

by the children in this study indicates their unfamiliarity

with these features.

Looping

Search looping refers to the re-activation of previously

executed searches. On the fully self-generated task, children

looped an average of one search (mean ! 1). Search looping

varied by success rate. Successful children looped five times

(mean ! 0.56), whereas unsuccessful children looped 10

times (mean ! 1.67) (Fig. 2).

Hyperlink looping means the reactivation of previously

visited hyperlinks. Children looped an average of one and a

half hyperlinks (mean ! 1.5). Like search looping, hyperlink looping varied by success levels. Successful children

looped 8 hyperlinks (mean ! 0.89), whereas unsuccessful

ones looped 15 hyperlinks (mean ! 2.5).

Looping varied by task (Table 1). Children looped an

equivalent number of hyperlinks on the fully self-generated

task and the research-oriented task (mean ! 1.93 vs.1.54,

respectively). However, they looped fewer hyperlinks on

the former task compared to the fact-based task (mean

! 1.93 vs. 5.1, respectively).

Search and hyperlink looping also varied by success

levels on the three tasks (Fig. 2). Successful children looped

searches and hyperlinks much less often on the three tasks

than did unsuccessful ones. Successful childrens mean

average of looping on the fully self-generated task was 0.88,

0.2 on the research-oriented task, and 2.2 on the fact-finding

task. Unsuccessful childrens mean average of looping was

3.5, 3.75, and 8, respectively.

Web Moves

The number of Web moves children made to complete

the fully self-generated tasks ranged from 12 to 110. Children made a total of 1,162 moves (mean ! 77). Web moves

are those that include all activities children performed to

complete the task (e.g., hyperlink activation, backtracking,

looping, exploratory move). The number of Web moves

varied by task (Table 1). Children made the highest number

of Web moves on the fully self-generated tasks (mean

JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN SOCIETY FOR INFORMATION SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGYNovember 2002

! 78), compared to the research-oriented task (mean ! 41)

and the fact-based task (mean ! 49).

The number of Web moves also varied by success levels

(Fig. 2). Surprisingly, successful children made more Web

moves to complete the fully self-generated task (mean

! 97) than did unsuccessful ones (mean ! 48). Children

who searched under broad topics, for example, retrieved

more information than those who searched under specific

ones. Compared to the two assigned tasks, successful children made more Web moves on the fully self-generated task

than they did on both the research-oriented and the factfinding tasks (means of 34 and 36, respectively).

Time

Children spent an average of 14 minutes and 35 seconds

(mean ! 14.35 minutes) to complete the fully self-generated task (Table 1). The mean time successful and unsuccessful children took to complete the fully self-generated

task was nearly the same (mean of 14.54 minutes vs. 14.75

minutes, respectively). On the research-oriented and factfinding tasks, however, successful children took less time to

complete them (mean of 8 minutes vs. 11.89 minutes, respectively) than did unsuccessful ones (mean of 16 minutes.

vs. 19.69 minutes, respectively) (Fig. 2). Overall, children

took the longest time to complete the fact-finding task

(mean ! 15.78 minutes) followed by the fully self-generated task (mean ! 14.35 minutes) and the research-oriented

task (mean ! 10.42 minutes).

Exploratory Moves

Five out of 15 children (33%) made exploratory moves

on the fully self-generated tasks. Exploratory moves are

those that are embedded in using the browsers features

(e.g., Find, Help, Bookmarks) and/or Yahooligans! Help

file. Two activated Yahooligans! on-line Help twice, but did

not select any option. One viewed Netscape Bookmarks and

did not launch any link, one made a search about oil

reserves using the Netscape Find option, and another used

the same option and performed three searches, one search

on greenbay, one on greenbay packers, and another on oil

reserves. Apparently, the Help file did not provide the help

the child was seeking. This is not surprising, because Yahooligans! Help does not give adequate guidance about

using the engine. Use of the Find command to locate

information about a topic indicates the childs lack of

knowledge about the purpose of this feature. The child who

activated Bookmarks was looking for sites related to his/her

topic but did not find any.

Exploratory moves varied by task (Table 1). While 33%

made these kind of moves on the fully self-generated tasks,

23% did so on the research-oriented task and 64% made

such moves on the fact-finding task.

Research Question 4. What task (fully self-generated

vs. fully assigned) do children prefer, and why?

To obtain a holistic view of childrens information seeking behavior, the research elicited their affective state in

terms of task preference at the conclusion of the research

experiment. Children were interviewed individually and

asked about the task they preferred the most and the reasons

for their preference. The majority of the children (47%)

preferred the fully self-generated task, 20% liked the research task, another 20% mentioned the fact-finding task,

and 13% were unsure. Only four children (27%) articulated

reasons for their task preference. One child preferred the

fully self-generated task because he/she was able to locate

the information sought. Another who favored the same task

mentioned the challenge that use of Yahooligans! provided him/her. He/she commented: . . . because I wanted to

figure out for myself that I can use [Yahooligans] and use it

well. One child preferred the fact-finding task and another

favored the research task for the same reason: ability to

locate the information sought. Satisfaction with the search

results was the driving force behind childrens task preference rather the task in itself. This finding is inconclusive,

however, because only 27% gave reasons for their task

preference, suggesting the need for further research in this

area of study.

Discussion

This study reported the findings of a research project that

examined the information seeking behavior and success of

seventh-grade science children in using Yahooligans! to

find information for a fully self-generated task. It compared

childrens behavior and success on this task to the behavior

and success they exhibited on the two fully assigned tasks

(research-oriented and fact-based) that they had performed

in the previous studies (Bilal, 2000, 2001). Children were

more successful on the fully self-generated task than on the

two assigned tasks. In addition, their information-seeking

behavior varied by task and by success levels. The findings

are discussed within the context of the four research questions posed.

Success

Most children (73%) found the information they sought

for their fully self-generated task. They were more successful on this task compared to research-oriented task (69%)

and the fact-finding task (50%). Childrens higher success

rate on the fully self-generated task was due to these factors:

first, they selected topics they were familiar with and had

interest in. Although 67% of the topics children chose were

research-oriented, they were simple; that is, they did not

contain many facets and were not complex in nature. Second, children were given a choice to modify their topics or

select new aspects of the topics if they did not locate

information of interest or did not find relevant information.

In cases when children did not find information on one of

the topics, they were able to do so on the second one. Third,

67% of the children were able to formulate a focus during

JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN SOCIETY FOR INFORMATION SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGYNovember 2002

1179

mediation that both the researcher and the school librarian

conducted. The flexibility in topic selection and modification combined with childrens preference of the fully selfgenerated task (by 47%) may have influenced their success

rate. This finding is congruent with the results of prior

studies (Garland, 1995; Hirsh, 1999; Oliver & Oliver, 1997;

Pitts, 1995; Small, 1999; Solomon, 1994), which revealed

that children were more motivated, challenged, and engaged

in completing their tasks when they selected topics that

interested them.

Cognitive Behavior

Children browsed much more than they searched by

keyword on the three tasks. In general, children were more

successful when they browsed than when they searched by

keyword. The difficulty children encountered in finding

relevant information was due to use of incorrect search

syntax and misspelling. As was found in the previous two

studies, the poor structure of Yahooligans! keyword searching contributed to childrens breakdowns. In fact, Yahooligans! does not employ comprehensive indexing of its sites.

Because it is a directory rather than a true search engine,

browsing tends to be a stronger feature than keyword

searching. The placement of the Search box above the

subject hierarchies in the search interface encourages keyword searching and makes it a priority to browsing, a design

that can be misleading to children. System developers need

to redesign keyword searching and enhance its capabilities,

as well as provide a spell-checking technique to minimize

childrens breakdowns in using the engine.

Childrens keyword searching included both single and

concrete concepts, which are typical of their cognitive developmental level, as identified by Bjorklund (2002) and

Piaget and Inhelder (1969). Although children were more

successful in finding relevant information for the fully selfgenerated task, 33% were unable to decide on a specific

focus to pursue or on the information to use from the results

they retrieved about their topic. One child who needed

information about poetry and later decided on poems by

Walt Whitman, for example, was undecided as to which

poem to select from the results he/she found. Similarly,

another child who sought information about Spice Girls

was uncertain as to the information to use and print about

the group. It is unclear why these children had a focus

formulation problem throughout the search process rather

than at task initiation. One possible explanation could be

due to childrens participation in an experiment rather than

a more natural information seeking incident. In their ASK

study, Belkin, Brooks, and Oddy (1982) found that in the

initial stage of information seeking, a user may not be able

to specify precisely what information he/she needs. Indeed,

a number of children experienced this problem when they

were asked to identify an aspect of the topic to pursue

during mediation. In fact, children may have expressed

general topics of interest because they were participating in

the experimental study, but they may not have actually had

1180

a specific information need at that time. The uncertainty

these children experienced during the search process may be

due to their inadequate level of topic knowledge. This

knowledge was not assessed in this study because the topics

that the children chose were not known in advance. The fact

that few children shifted focus and modified topics during

searching makes topic knowledge assessment an uneasy

task to undertake.

In giving children a choice to generate their own tasks

fully, one should factor in additional time to mediate the

tasks individually, monitor childrens activities closely to

diagnose and solve the problems they encounter, as well as

guide them at every stage of the search process.

Thirteen percent of the children used natural language

queries on the fully self-generated task. Although use of

natural language is typical of these childrens cognitive

developmental level, children should be exposed to effective Web training to equip them with the knowledge and

skills needed to use various Web search engines and the

browsers they embed.

Physical Behavior

Similar to their behavior on the two fully assigned tasks,

children activated the browsers Back command exclusively

to navigate among the Web pages they retrieved. No child

used shortcuts (e.g., History list, Go list), indicating unfamiliarity with these navigation commands. Children backtracked more on the fully self-generated task (mean ! 7.4)

than the research-oriented task (mean ! 6.07), but less often

than the fact-based task (mean ! 12.2). Children performed

the fully self-generated task on the second day of the research experiment and after they had completed the factbased task. It seems that they gained some skill in maneuvering within the Web environment. This finding is congruent with the results of prior research, which show that,

regardless of age, use the Back command is common among

Web users (Catledge & Pitkow, 1995; Large & Beheshti,

2000; Tauscher & Greenberg, 1997; Wang, Hawk, &

Tenopir, 2000). Consequently, backtracking by the children

in this study is considered typical of Web users behavior;

however, it raises the issue of efficiency in navigating the

Web, a problem that information professionals should address in their Web training programs.

Most children looped searches and hyperlinks. Because

the Web, by nature, creates disorientation and cognitive

overload on users, children are prone to loop hyperlinks and

searches when they use the Web due to memory recall

(Bjorklund, 2000; Siegler, 1998). One method to assist

children with memory recall is to teach them how to use a

browsers History list and the Go list. Keeping a list of the

sites they visit is another way to enhance childrens recall.

Children took more time to complete the fully selfgenerated task (mean ! 14.35 minutes) than the researchoriented task (mean ! 10.42 minutes), but an equivalent

time to perform the fact-based task (mean ! 15.78 minutes). Although most of the topics that children selected for

JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN SOCIETY FOR INFORMATION SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGYNovember 2002

their fully self-generated task were research-oriented, they

took longer to complete it than they did to accomplish the

assigned research-oriented task. Due to topic variety and

flexibility in changing aspects of topics and in modifying

topics during the search process, it is believed that fully

self-generated tasks may take longer to complete than fully

assigned tasks, especially when these tasks are researchoriented. Therefore, adequate time should be given to the

children when they perform fully self-generated tasks.

Task Preference

Most children (47%) preferred the fully self-generated

task to the two assigned tasks they had performed in the

previous studies (Bilal, 2000, 2001). The fact that childrens

satisfaction with the results was more important to them

than choosing their own topics is not surprising. Prior research of children and adults use of the Web revealed that

user satisfaction with search results provided them with a

sense of achievement (Bilal & Kirby, 2001; Kuhlthau,

1993). Although only 27% articulated reasons for their

preference of the fully self-generated tasks in the present

study, this finding should be used as a base for further

research in this area of study.

In sum, the findings of this study revealed these important characteristics about childrens information seeking

behavior and success in finding information in Yahooligans!

for a fully self-generated task.

(1) Children were more successful when they browsed than

when they searched by keyword.

(2) Children generated topics that were research-oriented

and broad in nature. Sixty-seven percent were able to

formulate a focus and select a specific aspect of interest

during topic mediation, while 33% remained undecided

about the aspect to choose.

(3) Children who searched under their initial broad topics

remained undecided about the information to select

from the results they retrieved.

(4) Most children opted to search under broader terms they

extracted from their initial topics rather than the more

specific terms included in their mediated topics.

(5) Thirteen percent used natural language queries, and

another 13% misspelled terms repeatedly.

(6) Thirty-three percent made exploratory moves in the

Netscape browser to locate the information they needed.

No child used the Help features in Yahooligans! or the

browser.

(7) Children backtracked and looped searches and hyperlinks, but not as often as they did for the two assigned

tasks they had performed in the previous studies.

(8) Children need adequate training in using Web search

engines, in navigating in a Web browsers space, as

well as in negotiating information problems and formulating a clear focus about topics of interest.

(9) Overall, children had less difficulty with the fully selfgenerated task than with the two assigned tasks.

Conclusions

The fact that children were more successful in finding

information for the fully self-generated task and had less

difficulty with it compared to the two fully assigned tasks

should not entirely confirm that fully self-generated tasks

are better suited for Web use than fully assigned tasks. As

mentioned earlier, few children, including successful ones,

experienced uncertainty and had decision-making problems

about the information to select from the results they retrieved about their topics of interest. Thus, childrens success should not be judged solely on finding the desired

information. The process children adopt in seeking information, the meaning or sense making they derive from

the information they find, the way they use the information

are important factors in evaluating the information-seeking

process.

When children are given a choice to generate their own

tasks fully, they should be guided and supported affectively

from the time they initiate their topics to the time they

complete them. Most children chose topics that were broad

in nature and, therefore, necessitated mediation to identify

the true information need. Topic mediation is essential to

assist children in formulating a clear focus to pursue. In

addition, children should be trained in identifying their

information need so that they develop a focus and become

certain about aspects of topics to pursue. As children use of

the Web increases at schools and homes, they need to

acquire an adequate level of knowledge of the Information

Search Process (ISP) described by Kuhlthau (1993), for

example, to become more skilled in initiating and completing tasks successfully. Information seeking skills are vital

for these children especially as they use the Web outside

class context where mediation is not provided.

Children browsed more than searched by keyword on the

three tasks. The breakdowns children experienced with

keyword searching was mainly due to Yahooligans! poor

structure of keyword searching. Although Yahooligans! is

designed for children ages 712, it does not support their

information seeking effectively. This is because Yahooligans! is considered a directory rather than a search engine.

However, placing the Search box above the subject hierarchies in the search interface encourages keyword searching

and gives it a priority to browsing. The fact that the engine

lacks a spell-checking technique, has inadequate guidance

under its Help file, and does not provide a corrective feedback method, make its use difficult not only by children, but

also by adults (Bilal & Kirby, 2002). System designers

should reevaluate this engine to support childrens information seeking.

The need for Web training should not be underestimated.

Information professionals should capitalize on childrens

motivation in using the Web by developing formal Web

training programs that incorporate use of models of the

information-seeking process, such as the Big6 Skills (Eisenberg & Berkowitz, 1990). The affective aspect of information seeking should be incorporated into teaching informa-

JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN SOCIETY FOR INFORMATION SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGYNovember 2002

1181

APPENDIX 1.

Childrens fully self-generated topics.a

I want information about Ebola virus

What can dogs do to help out other people

Information about veterinarians as a career

What is the main threat to panda bears survival

I want to find information on large oil reserves

I want information about pc cd-rom games

I want to find information about chat rooms

I want to find information about computer games

I want to find information about poetry

Information on endangered species

Information on Michael Jordan

Information about movies

Information about packers

Information about looney tunes

Summer olympic games

I want to find information on music and movies

I want to find information on the spice girls

I want to find ice skating and acting

I want to find a topic on baseball and gymnastics

I want information about psychology

Information about law

Information about music

a

Topics before mediation.

tion literacy skills. Kuhlthaus model of the ISP (1993),

which combines the cognitive, physical, and affective behaviors of information seeking can be integrated with the

Big6 Skills model, for example, to derive a holistic model

on which to build effective information literacy skills programs for children.

As children use the Web as the major source for their

school projects (Pew Research Center, 2001), there is a need

to learn more about these young peoples informationseeking behavior and success. The Web is a complex,

unstructured information retrieval system that not only children, but also adults have a difficult time constructing a

meaningful mental model of [it] (Jacobson, 1995, p. 71).

Questions that bear further study are: What methodologies

are best suited to examine childrens information-seeking

behavior and success on the Web? What type of tasks do

children prefer to perform on the Web, and how do these

tasks influence their information-seeking behavior and success? How does the interface design of Web search engines

affect childrens information-seeking behavior and success?

How does childrens information seeking on the Web lead

to meaningful learning?

The taxonomy of tasks presented in this study describes

the differences among various types of tasks. It is recommended for use by other researchers as they perform research in these areas of study.

Acknowledgments

This research is supported by a grant from the Office of

Research, The University of Tennessee, Knoxville. The

author wishes to thank the educational advisor of the county

who gave permission to use the Middle School as the site

1182

for this study. Thanks are also extended to the children and

the school librarian. The cooperation and support of the

School Principal and Assistant Principal are highly appreciated. Thanks to Peiling Wang, Bill Robinson, and Doug

Raber, Associate Professors, School of Information Sciences at

The University of Tennessee-Knoxville, for their comments and suggestions.

References

Belkin, N.J., Brooks, H.M., & Oddy, R.N. (1982). ASK for information

retrieval. Journal of Documentation, 38(2), 6171.

Bilal, D. (1998). Childrens search processes in using World Wide Web

search engines: An exploratory study. Proceedings of the 61st ASIS

Annual Meeting, 35, October 24 29, 1998, Pittsburgh, PA (pp. 4553).

Medford, NJ: Information Today, Inc.

Bilal, D. (1999). Web search engines for children: A comparative study and

performance evaluation of Yahooligans!, Ask Jeeves for Kids, and

Super Snooper. Proceedings of the 62nd ASIS Annual Meeting,

October 31Nov. 4, 1999. Washington, DC (pp. 70 83). Medford, NJ:

Information Today, Inc.

Bilal, D. (2000). Childrens use of the Yahooligans! search engine. I.

Cognitive, physical, and affective behaviors on fact-based search tasks.

Journal of the American Society for Information Science, 51(7), 646

665.

Bilal, D. (2001). Childrens use of the Yahooligans! search engine. II.

Cognitive and physical behaviors on research tasks. Journal of the

American Society for Information Science and Technology, 52(2), 118

136.

Bilal, D., & Kirby, J. (2001). Factors influencing childrens and adults

information seeking on the Web: Results of two studies. Proceedings of

the 64th ASIST Annual Meeting, November 4 8, 2001, Washington,

DC (pp. 126 140). Medford, NJ: Information Today, Inc.

Bilal, D., & Kirby, J. (2002). Differences and similarities in information

seeking on the Web: Children and adults as Web users. Information

Processing & Management, 38(5), 649 670.

Bjorklund, D.F. (2000). Childrens thinking: Developmental function and

individual differences. Stamford, CT: Wadsworth.

Borgman, C.L., et. al. (1995). Childrens searching behavior on browsing

and keyword searching online catalogs: The Science Library Catalog

project. Journal of the American Society for Information Science, 46(9),

663 684.

Broch, E. (2000). Childrens search engines from an information search

process perspective. School Library Media Research. http://www.

als.org/aasl/SLMR/childrens_main.html. Accessed on November 20,

2001.

Bystrom, K, & Jarvelin, K. (1995). Task complexity affects information

seeking and use. Information Processing & Management, 31(2), 191

213.

Catledge, L.D., & Pitkow, J.E. (1995). Characterizing browsing strategies in

the World Wide Web. Available: http://www.igd.fhg.de/www/www95/

proceedings/ papers/80/userpatterns/UserPatterns.Paper4.formatted.

html. Accessed on September 8,1998.

Dervin, B. (1983). Information as a user construct: The relevance of

perceived information needs to synthesis and interpretation. In S.A.

Ward, & L.A. Reed (Eds.), Knowledge structure and use: Implications

for synthesis and Interpretation. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University

Press.

Dimitrof, A., & Wolfram, Z. (1995). Searcher response in a hypertextbased bibliographic information retrieval system. Journal of the American Society for Information Science, 46, 2236.

Eisenberg, M.B., & Berkowitz, R.E. (1990). Information problem-solving:

The big six skills approach to library and information skills instruction.

Norwood, NJ: Ablex Publishing.

Garland, K. (1995). The information search process: A study of elements

associated with meaningful research tasks. School Libraries Worldwide,

1(1), 4153.

JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN SOCIETY FOR INFORMATION SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGYNovember 2002

Gross, M. (1997). Pilot study on prelevance of imposed queries in a school

library media center. School Library Media Quarterly, 25(3), 157166.

Hirsh, S.G. (1997). How do children find information on different types of

tasks? Childrens use of the Science Library Catalog. Library Trends,

45(4), 725745.

Hirsh, S.G. (1999). Childrens relevance criteria and information-seeking

on electronic resources. Journal of the American Society for Information

Science, 50(14), 12651283.

Ingwersen, P. (1996). Cognitive perspectives of information retrieval interaction: Elements of a cognitive IR theory. Journal of Documentation,

51(1), 350.

Jacobson, F.F. (1995). From Dewey to Mosaic: Considerations in interface

design for children. Internet Research: Electronic Networking Applications and Policy, 5(2), 6773.

Jansen, M.J., Spink, A., & Saracevic, T. (2000). Real life, real users, real

needs: A study of analysis of user queries on the Web. Information

Processing & Management, 36(2), 207227.

Kafai, Y., & Bates. M.J. (1997). Internet web-searching instruction in the

elementary classroom: Building a foundation for information literacy.

School Library Media Quarterly, 25(2), 103111.

Kuhlthau, C.C. (1993). Seeking meaning: A process approach to library

and information services. Norwood: Ablex Publishing.

Large, A., & Beheshti, J. (2000). The Web as a classroom resource:

Reactions from the users. Journal of the American Society for Information Science, 51(12), 1069 1080.

Large, A., Beheshti, J., & Breuleux, A. (1998). Information seeking in a

multimedia environment by primary school students. Library and Information Science Research, 20, 343376.

Large, A., Beheshti, J., & Moukad, H. (1999). Information seeking on the

Web: Navigational skills of grade-six primary school students. Proceedings of the 62nd ASIS Annual Meeting, October 31Nov. 4, 1999.

Washington, DC (pp. 84 97). Medford, NJ: Information Today, Inc.