Professional Documents

Culture Documents

First Metro Investment vs. Estate of Del Sol

Uploaded by

Emir MendozaCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

First Metro Investment vs. Estate of Del Sol

Uploaded by

Emir MendozaCopyright:

Available Formats

First Metro Investment vs.

Estate of Del Sol (2001)

Petitioners: FIRST METRO INVESTMENT CORPORATION

Respondents: ESTE DEL SOL MOUNTAIN RESERVE, INC., VALENTIN S. DAEZ, JR.,

MANUEL Q. SALIENTES, MA. ROCIO A. DE VEGA, ALEXANDER G. ASUNCION, ALBERTO

M. LADORES, VICENTE M. DE VERA, JR., AND FELIPE B. SESE

Ponente: DE LEON, JR.

Topic: Remedies for Breach

SUMMARY: (1-2 sentence summary of facts, issue, ratio and ruling)

FACTS:

-

January 31, 1978: FMIC loaned Este del Sol P7.3M for the construction of a resort in

Montalban, Rizal with 16% interest per annum, subject to (a) a onetime penalty of

20% of the amount due which shall bear interest at the highest rate permitted by

law from the date of default until full payment, (b) liquidated damages at 2% per

month compounded quarterly on the unpaid balance and accrued interests

together with all the penalties, fees, expenses or charges until the balance is fully

paid, and (c) Attorneys fees equivalent to 25% for the sum sought to be recovered.

The loans were released on a staggered basis.

On the same day, as provided in the loan agreement, the parties also entered into an

Underwriting Agreement, (a) whereby FMIC shall underwrite on a best-efforts basis the

public offering of 120,000 common shares of Este del Sol's capital stock for a one-time

underwriting fee of P200,000.00; (b) an annual supervision fee of P200,000 for four

consecutive years to be paid to FMIC for supervising the public offering of the shares;

(c) and a consultancy fee of P332,500.00 per annum for 4 consecutive years to

FMIC.

Simultaneously, a Consultancy Agreement was executed whereby Estedel Sol engaged

FMICs services for a fee as consultant to render general consultancy services

February 22, 1978: FMIC billed Este del Sol for the underwriting (P200k) and

supervision fees (P200k), as well as P1.3M worth of consultancy fees for 4 years. These

were all deducted from the first release of the loan.

June 23, 1980: Este del Sol failed to meet the payment schedules, incurring P12.6M due

to FMIC.

FMIC caused the foreclosure of P7.5M worth of properties mortgaged by Este del Sol.

Of the P9M from the foreclosure and auction, P3.1M was deducted for attorneys fees

and P5.8M for interests and penalties, and partly on the principal.

November 11: FMIC initiated a collection suit against respondents-sureties for the

remaining P6.8M owed by Este del Sol.

The respondents argued that the Underwriting and Consultancy Agreements were

integral parts of the Loan Agreement and were merely subterfuges to camouflage the

usurious interest charged by FMIC.

The trial court sided with FMIC and ordered respondents to pay the P6.8M balance.

The CA reversed. It found and declared that the fees provided for in the Underwriting

and Consultancy Agreements were mere subterfuges to camouflage the excessively

usurious interest charged by FMIC on the loan of Este del Sol; and that the stipulated

penalties, liquidated damages and attorney's fees were "excessive, iniquitous,

unconscionable and revolting to the conscience. It declared that in lieu thereof, the

stipulated one time 20% penalty on the amount due and 10% of the amount due as

attorney's fees would be reasonable and suffice to compensate FMIC for those items.

Thus, it ordered FMIC to pay or reimburse Este del Sol P971,000.00 representing the

difference between what is due to FMIC and what is due to Este del Sol.

Thus, this appeal by FMIC, assailing the factual findings and conclusion of the CA. (SC:

We are not a trier of facts.)

ISSUES:

WoN the Underwriting and Consultancy Agreements were merely camouflages for

usurious interest

o YES. First, there is no merit to petitioner FMIC's contention that Central Bank

Circular No. 905 which took effect on January 1, 1983 and removed the ceiling

on interest rates for secured and unsecured loans, regardless of maturity, should

be applied retroactively to a contract executed on January 31, 1978, as in this

case, while the Usury Law was in full force and effect. It is an elementary rule of

contracts that the laws, in force at the time the contract was made and entered

into, govern it. More significantly, Central Bank Circular No. 905 did not repeal

nor in any way amend the Usury Law but simply suspended the latter's effectivity.

o Second, the form of the contract is not conclusive for the law will not permit a

usurious loan to hide itself behind a legal form. Parol evidence is admissible to

show that a written document though legal in form was in fact a device to cover

usury.

o Several facts and circumstances taken altogether show that the Underwriting and

Consultancy Agreements were simply cloaks or devices to cover an illegal

scheme employed by FMIC to conceal and collect excessively usurious interest:

The Underwriting and Consultancy Agreements were executed

simultaneously with the Loan Agreement and were set to mature or shall

remain effective during the same period of time.

The P1.3M for four years worth of consultancy fees was charged in

February 1978 when the agreement is for P332.5K for every year.

The P1.3M, along with the underwriting and supervision fees, were

charged from the first release of the loan. Thus, P1.73M reverted to FMIC

as part of the loan to Este del Sol.

FMIC failed to comply with its underwriting and consultancy obligations,

notwithstanding the fact that these were not necessary since Este del

Sols marketing arm and officers were more than capable.

o The underwriting and consultancy agreements were essential conditions for the

grant of the loan. An apparently lawful loan is usurious when it is intended that

additional compensation for the loan be disguised by an ostensibly unrelated

NOTES:

contract providing for payment by the borrower for the lenders services which

are of little value or which are not in fact to be rendered.

Art. 1957: Contracts and stipulations, under any cloak or device whatever,

intended to circumvent the laws against usury shall be void. The borrower may

recover in accordance with the laws on usury.

In usurious loans, the entire obligation does not become void because of an

agreement for usurious interest; the unpaid principal debt still stands and

remains valid but the stipulation as to the usurious interest is void, consequently,

the debt is to be considered without stipulation as to the interest.

Angel Jose Warehousing Co., Inc. v. Child Enterprises: In simple loan

with stipulation of usurious interest, the prestation of the debtor to pay the

principal debt, which is the cause of the contract (Article 1350, Civil

Code), is not illegal. The illegality lies only as to the prestation to pay the

stipulated interest; hence, being separable, the latter only should be

deemed void, since it is the only one that is illegal.

You might also like

- The Memo'Document2 pagesThe Memo'Anonymous GZ9IDkNo ratings yet

- The 5 Elements of the Highly Effective Debt Collector: How to Become a Top Performing Debt Collector in Less Than 30 Days!!! the Powerful Training System for Developing Efficient, Effective & Top Performing Debt CollectorsFrom EverandThe 5 Elements of the Highly Effective Debt Collector: How to Become a Top Performing Debt Collector in Less Than 30 Days!!! the Powerful Training System for Developing Efficient, Effective & Top Performing Debt CollectorsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- ZIM - Company Law ModuleDocument61 pagesZIM - Company Law ModuleAlbert Ziwome100% (14)

- Case Digest GR 117660Document2 pagesCase Digest GR 117660Zarina PemblingNo ratings yet

- Kauffman Vs PNBDocument3 pagesKauffman Vs PNBNoeh Ella de ChavezNo ratings yet

- Wee Sion Ben V Semexco Zest-O Marketing Corp., G.R. No. 153898, October 18, 2007Document1 pageWee Sion Ben V Semexco Zest-O Marketing Corp., G.R. No. 153898, October 18, 2007Lyle BucolNo ratings yet

- Palmares V CA DigestDocument5 pagesPalmares V CA DigestStefan Salvator100% (1)

- SPOUSES EDUARDO and LYDIA SILOS, Petitioners, vs. PHILIPPINE NATIONAL BANK, RespondentDocument3 pagesSPOUSES EDUARDO and LYDIA SILOS, Petitioners, vs. PHILIPPINE NATIONAL BANK, RespondentPam Ramos100% (3)

- People vs. Olarbe DigestDocument4 pagesPeople vs. Olarbe DigestEmir Mendoza100% (5)

- People vs. San Jose DigestDocument7 pagesPeople vs. San Jose DigestEmir Mendoza100% (1)

- People vs. Salga DigestDocument5 pagesPeople vs. Salga DigestEmir Mendoza100% (2)

- Revilla vs. Sandiganbayan DigestDocument7 pagesRevilla vs. Sandiganbayan DigestEmir Mendoza50% (2)

- Department of Education vs. Dela Torre DigestDocument2 pagesDepartment of Education vs. Dela Torre DigestEmir Mendoza100% (2)

- Radiowealth Finance Company, Inc. vs. Pineda, Jr. DigestDocument2 pagesRadiowealth Finance Company, Inc. vs. Pineda, Jr. DigestEmir Mendoza100% (2)

- Pen Vs SantosDocument1 pagePen Vs SantosDaniela Erika Beredo Inandan100% (1)

- Deed of Corporate GuaranteeDocument11 pagesDeed of Corporate GuaranteeridhofauzisNo ratings yet

- First Metro Investment Corporation Vs Este Del Sol 369 SCRA 99Document2 pagesFirst Metro Investment Corporation Vs Este Del Sol 369 SCRA 99Roseve Batomalaque100% (1)

- 19 Sps. Tecklo Vs Rural Bank of PamplonaDocument2 pages19 Sps. Tecklo Vs Rural Bank of PamplonaAngelo NavarroNo ratings yet

- Banco Atlantico V Auditor GeneralDocument6 pagesBanco Atlantico V Auditor GeneralAnna VeluzNo ratings yet

- Facts:: Eastern Shipping Lines, Inc. vs. Hon. Court of Appeals and Mercantile Insurance Company, INCDocument2 pagesFacts:: Eastern Shipping Lines, Inc. vs. Hon. Court of Appeals and Mercantile Insurance Company, INCEmilio Pahina100% (1)

- Hi Cement vs. InsularDocument2 pagesHi Cement vs. InsularIyah MipangaNo ratings yet

- Jimenez v. BucoyDocument2 pagesJimenez v. BucoyReymart-Vin MagulianoNo ratings yet

- GSIS Vs CA Case DigestDocument1 pageGSIS Vs CA Case DigestPrinceCatayloNo ratings yet

- Tan Vs CADocument3 pagesTan Vs CAAlykNo ratings yet

- Herrera Vs PetrophilDocument2 pagesHerrera Vs PetrophilTrem GallenteNo ratings yet

- Adorable Vs CADocument5 pagesAdorable Vs CAHariette Kim Tiongson0% (1)

- DBP Vs NLRCDocument2 pagesDBP Vs NLRCKym HernandezNo ratings yet

- Case No. 9 Republic v. GrijaldoDocument2 pagesCase No. 9 Republic v. GrijaldoAnjela Ching50% (2)

- Eastern Shipping Lines v. CADocument3 pagesEastern Shipping Lines v. CAEmir MendozaNo ratings yet

- 134.diego vs. Fernando GR No. L 15128 August 25 1960 AntichresisDocument1 page134.diego vs. Fernando GR No. L 15128 August 25 1960 AntichresisAnonymous 53bboBNo ratings yet

- Visayan Surety and Insurance Vs CA - G.R. No. 127261. September 7, 2001Document5 pagesVisayan Surety and Insurance Vs CA - G.R. No. 127261. September 7, 2001Ebbe DyNo ratings yet

- Munasque-v-CA G-R-No-L-39780-November-11-1985Document2 pagesMunasque-v-CA G-R-No-L-39780-November-11-1985Christine Gel MadrilejoNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 194964-65Document3 pagesG.R. No. 194964-65Adrian Olaguer AguasNo ratings yet

- Nego Digests 32 - 34Document4 pagesNego Digests 32 - 34Cla BANo ratings yet

- Heck vs. GamotinDocument1 pageHeck vs. GamotinJeru SagaoinitNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 156940 December 14, 2004 Associated Bank (Now Westmont Bank) vs. TanDocument3 pagesG.R. No. 156940 December 14, 2004 Associated Bank (Now Westmont Bank) vs. TanThereseSunicoNo ratings yet

- Florencia Huibonhoa vs. Court of Appeals G.R. No. 95897, December 14, 1999 320 SCRA 625Document2 pagesFlorencia Huibonhoa vs. Court of Appeals G.R. No. 95897, December 14, 1999 320 SCRA 625Sofia DavidNo ratings yet

- Tanada V Angara-PILDocument62 pagesTanada V Angara-PILEllieNo ratings yet

- Carbonell v. Metropolitan BankDocument2 pagesCarbonell v. Metropolitan Bankbantucin davooNo ratings yet

- Phil-Am vs. Ramos, G.R. No. L-20978, Feb. 28, 1966 Case DigestDocument1 pagePhil-Am vs. Ramos, G.R. No. L-20978, Feb. 28, 1966 Case Digestbeingme2No ratings yet

- Crismina Garments Vs CADocument2 pagesCrismina Garments Vs CAJude ChicanoNo ratings yet

- CBP Vs CaDocument2 pagesCBP Vs CaGale Charm SeñerezNo ratings yet

- Pantaleon Vs Amex Case DigestDocument2 pagesPantaleon Vs Amex Case DigestEmelie Marie Diez100% (2)

- DIGEST de Castro Vs LongaDocument2 pagesDIGEST de Castro Vs LongasarmientoelizabethNo ratings yet

- Case 2 Miguel J. Osorio Pension Foundation vs. CADocument2 pagesCase 2 Miguel J. Osorio Pension Foundation vs. CAlenvfNo ratings yet

- Republic Planters Bank Vs CADocument2 pagesRepublic Planters Bank Vs CARona Joy Alderite100% (2)

- Mesina vs. IACDocument1 pageMesina vs. IACMae NavarraNo ratings yet

- Borromeo vs. CADocument3 pagesBorromeo vs. CAcmv mendozaNo ratings yet

- La Chemise Lacoste, S.A. vs. FernandezDocument6 pagesLa Chemise Lacoste, S.A. vs. FernandezJeliSantosNo ratings yet

- OCA v. LiangcoDocument1 pageOCA v. LiangcoVincent Quiña PigaNo ratings yet

- Linsangan v. Atty. TolentinoDocument2 pagesLinsangan v. Atty. TolentinoAbegail GaledoNo ratings yet

- Case DigestDocument3 pagesCase DigestNivra Lyn EmpialesNo ratings yet

- Marilen G. Soliman vs. Atty. Ditas Lerios-AmboyDocument2 pagesMarilen G. Soliman vs. Atty. Ditas Lerios-AmboyPhil Edward Marcaida VillanuevaNo ratings yet

- Dario Nacar Vs Gallery Frames DigestDocument2 pagesDario Nacar Vs Gallery Frames DigestJay Jasper Lee100% (8)

- Investors Finance Corporation vs. Autoworld Sales CorporationDocument3 pagesInvestors Finance Corporation vs. Autoworld Sales CorporationMike E DmNo ratings yet

- Allied Banking Corporation V Court of Appeals DigestDocument2 pagesAllied Banking Corporation V Court of Appeals DigestIna Villarica67% (3)

- Eastern Shipping Lines vs. CA Case DigestDocument1 pageEastern Shipping Lines vs. CA Case DigestReth Guevarra100% (1)

- UCPB Vs Spouses BelusoDocument9 pagesUCPB Vs Spouses BelusoOke HarunoNo ratings yet

- Canlapan Vs BalayoDocument2 pagesCanlapan Vs BalayoJa AzisNo ratings yet

- Digest Credit Trans CasesDocument7 pagesDigest Credit Trans CasesGracelyn Enriquez Bellingan100% (1)

- Case DigestDocument3 pagesCase DigestRhaj Łin KueiNo ratings yet

- MELVIN COLINARES Vs CADocument2 pagesMELVIN COLINARES Vs CAchaNo ratings yet

- Tomimbang V 2Document10 pagesTomimbang V 2denelizaNo ratings yet

- Reymundo v. SunicoDocument3 pagesReymundo v. SunicoKym AlgarmeNo ratings yet

- BPI Vs CA Credit DigestDocument6 pagesBPI Vs CA Credit Digestmaria luzNo ratings yet

- CASE NO. 6 First Metro Investment Corporation v. Este Del Sol Mountain Reserve, Inc.Document4 pagesCASE NO. 6 First Metro Investment Corporation v. Este Del Sol Mountain Reserve, Inc.John Mark MagbanuaNo ratings yet

- First Metro Investment Corporation vs. Este Del Sol Mountain Reserve, Inc FactsDocument2 pagesFirst Metro Investment Corporation vs. Este Del Sol Mountain Reserve, Inc FactsKaren Ryl Lozada BritoNo ratings yet

- First Metro Investment Corporation vs. Este de SolDocument2 pagesFirst Metro Investment Corporation vs. Este de SolLoNo ratings yet

- First Metro Investment vs. Este. Del SolDocument3 pagesFirst Metro Investment vs. Este. Del SolAce MarjorieNo ratings yet

- 54 First Metro Investment V Este Del SolDocument15 pages54 First Metro Investment V Este Del Soljuan aldabaNo ratings yet

- Labay vs. Sandiganbayan DigestDocument4 pagesLabay vs. Sandiganbayan DigestEmir Mendoza100% (2)

- Pacho vs. Judge Lu DigestDocument3 pagesPacho vs. Judge Lu DigestEmir MendozaNo ratings yet

- People vs. Ubungen DigestDocument3 pagesPeople vs. Ubungen DigestEmir MendozaNo ratings yet

- People vs. Rojas DigestDocument3 pagesPeople vs. Rojas DigestEmir MendozaNo ratings yet

- Comelec 2025 Aes TorDocument70 pagesComelec 2025 Aes TorEmir MendozaNo ratings yet

- Office of The Court Administrator vs. Alaras DigestDocument3 pagesOffice of The Court Administrator vs. Alaras DigestEmir MendozaNo ratings yet

- Juego-Sakai vs. Republic DigestDocument2 pagesJuego-Sakai vs. Republic DigestEmir Mendoza100% (3)

- Montejo vs. Commission On Audit DigestDocument2 pagesMontejo vs. Commission On Audit DigestEmir MendozaNo ratings yet

- People vs. Gajila DigestDocument3 pagesPeople vs. Gajila DigestEmir MendozaNo ratings yet

- Department of Transportation vs. Philippine Petroleum Sea Transport Association DigestDocument8 pagesDepartment of Transportation vs. Philippine Petroleum Sea Transport Association DigestEmir Mendoza100% (1)

- Republic vs. Decena DigestDocument3 pagesRepublic vs. Decena DigestEmir MendozaNo ratings yet

- Philippine Health Insurance Corporation vs. Commission On Audit (July 2018) DigestDocument3 pagesPhilippine Health Insurance Corporation vs. Commission On Audit (July 2018) DigestEmir MendozaNo ratings yet

- Heirs of Arce vs. Department of Agrarian Reform DigestDocument3 pagesHeirs of Arce vs. Department of Agrarian Reform DigestEmir MendozaNo ratings yet

- Radiowealth Finance Company, Inc. vs. Pineda, JR PDFDocument7 pagesRadiowealth Finance Company, Inc. vs. Pineda, JR PDFEmir MendozaNo ratings yet

- Anonymous vs. Judge Buyucan DigestDocument4 pagesAnonymous vs. Judge Buyucan DigestEmir MendozaNo ratings yet

- Ramos vs. People DigestDocument2 pagesRamos vs. People DigestEmir Mendoza100% (1)

- People vs. de Vera DigestDocument4 pagesPeople vs. de Vera DigestEmir MendozaNo ratings yet

- Land Bank vs. Prado Verde Corporation DigestDocument3 pagesLand Bank vs. Prado Verde Corporation DigestEmir MendozaNo ratings yet

- Bangko Sentral NG Pilipinas vs. Banco Filipino Savings and Mortgage Bank DigestDocument3 pagesBangko Sentral NG Pilipinas vs. Banco Filipino Savings and Mortgage Bank DigestEmir Mendoza100% (3)

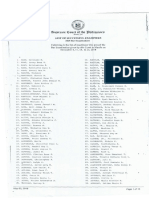

- Bar 2018 ResultsDocument15 pagesBar 2018 ResultsEmir MendozaNo ratings yet

- Moreno vs. Kahn DigestDocument2 pagesMoreno vs. Kahn DigestEmir Mendoza100% (3)

- People vs. Balubal DigestDocument3 pagesPeople vs. Balubal DigestEmir MendozaNo ratings yet

- Masbate vs. Relucio DigestDocument3 pagesMasbate vs. Relucio DigestEmir Mendoza100% (5)

- Philippine Assisted Reproductive Technologies Act (Proposed Version by Emir Mendoza)Document5 pagesPhilippine Assisted Reproductive Technologies Act (Proposed Version by Emir Mendoza)Emir MendozaNo ratings yet

- Tata Steel & Bhushan SteelDocument7 pagesTata Steel & Bhushan Steelshahal tkNo ratings yet

- Weatherly International PLC V Bruni & McLaren and Another ( (P) A 191/2006) (2011) NAHC 263 (14 September 2011)Document12 pagesWeatherly International PLC V Bruni & McLaren and Another ( (P) A 191/2006) (2011) NAHC 263 (14 September 2011)André Le RouxNo ratings yet

- Endorsement AgreementDocument4 pagesEndorsement AgreementRocketLawyerNo ratings yet

- Filed: Patrick FisherDocument6 pagesFiled: Patrick FisherScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Persons - Waiver of Rights - 3 - Dona Adela vs. TidcorpDocument4 pagesPersons - Waiver of Rights - 3 - Dona Adela vs. TidcorpRalph Jarvis Hermosilla Alindogan100% (1)

- Older Adults and BankruptcyDocument28 pagesOlder Adults and BankruptcyvictorNo ratings yet

- Jhen Powerpoint Law 1Document95 pagesJhen Powerpoint Law 1Farah Tolentino NamiNo ratings yet

- Right Under Garnishee OrderDocument16 pagesRight Under Garnishee OrderTeja RaviNo ratings yet

- China Bank Vs CADocument2 pagesChina Bank Vs CAVanya Klarika NuqueNo ratings yet

- China Banking Corporation Vs CADocument5 pagesChina Banking Corporation Vs CAFrancis CastilloNo ratings yet

- Mattel Motion For Appointment of ReceiverDocument22 pagesMattel Motion For Appointment of Receiverpropertyintangible100% (2)

- United States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitDocument7 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Fidic Form Contract Lecture NoteDocument14 pagesFidic Form Contract Lecture NoteAlgel YeeNo ratings yet

- Decree Dated October 28, 1988 Referring To Contract and Other LiabilitiesDocument19 pagesDecree Dated October 28, 1988 Referring To Contract and Other LiabilitiesSambath KheangNo ratings yet

- Jahn Design ProposalDocument597 pagesJahn Design ProposalAnonymous 6f8RIS6No ratings yet

- PARTNERSHIP Notes (Prelim)Document13 pagesPARTNERSHIP Notes (Prelim)Bedynz Mark PimentelNo ratings yet

- Abrera vs. BarzaDocument11 pagesAbrera vs. BarzaVenn Bacus RabadonNo ratings yet

- Beaumont v. PrietoDocument2 pagesBeaumont v. PrietoNicole KalingkingNo ratings yet

- Secured Transactions Musselman 2000Document84 pagesSecured Transactions Musselman 2000sacajaweahNo ratings yet

- Stronghold Insurance Company Vs Republic-AsahiDocument2 pagesStronghold Insurance Company Vs Republic-AsahiJurico Alonzo100% (2)

- Contracts TableDocument1 pageContracts TableulticonNo ratings yet

- Vivares v. ReyesDocument3 pagesVivares v. ReyesElah ViktoriaNo ratings yet

- Family Law I: Assignment I: Name: Gaurvi Arora Roll ID: 19IP63016Document3 pagesFamily Law I: Assignment I: Name: Gaurvi Arora Roll ID: 19IP63016Gaurvi AroraNo ratings yet

- Donald TrumpDocument154 pagesDonald TrumpzinisaloNo ratings yet

- Notes - Obli 2Document14 pagesNotes - Obli 2Matthew WittNo ratings yet

- Chapter 21 - Debt Restructuring, Corporate Reorganizations, and LiquidationsDocument41 pagesChapter 21 - Debt Restructuring, Corporate Reorganizations, and LiquidationsDieter LudwigNo ratings yet