Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Wound Infection

Uploaded by

elenCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Wound Infection

Uploaded by

elenCopyright:

Available Formats

OPE N ACCESS

ORIGINAL STUDY

Risk factors for wound infection after

lower segment cesarean section

Fathia E. Al Jama

ABSTRACT

Address for Correspondence:

Fathia E. Al Jama

Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, King Fahad

University Hospital, College of Medicine, Dammam

University, Dammam, Saudi Arabia

Email: fathiaaj@gmail.com

http://dx.doi.org/10.5339/qmj.2012.2.9

Submitted: 1 September 2012

Accepted: 1 December 2012

2012 Al Jama, licensee Bloomsbury Qatar Foundation Journals.

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the

Creative Commons Attribution license CC BY 3.0, which permits

unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly cited.

Cite this article as: Al Jama FE. Risk factors for

wound infection after lower segment cesarean

section, Qatar Medical Journal 2012:2 http://dx.

doi.org/10.5339/qmj.2012.2.9

The incidence of post caesarean wound infection and

independent risk factors associated with wound infection were retrospectively studied at a tertiary care

hospital.

A retrospective case controlled study of 107 patients

with wound infection after lower segment caesarean

section (LSCS) was undertaken between January 1998

and December 2007. The control group comprised of

340 patients selected randomly from among those who

had LSCS during the study period with no wound

infection. Chart reviews of patients with wound

infection were identified using the definitions from the

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's National

Nosocomial Infections Surveillance Systems. Comparisons for categorical variables were performed using the

X 2 or Fisher exact test. Continuous variables were

compared using the 2-tailed Student t test. P , 0.05

was considered significant. Logistic regression

determined the independent risk factors.

The overall wound infection rate in the study was

4.2% among 2 541 lower transverse CS. The

independent risk factors identified for wound infection

were, obesity, duration of labor .12 hours, and no

antenatal care. Patients' age and parity, diabetes

mellitus, premature rupture of membranes (PROM)

.8 hours and elective vs. emergency surgery was not

found to be significantly associated with wound

infection.

Conclusion: The independent risk factors could be

incorporated into the policies for surveillance and

prevention of wound infection. Antibiotic prophylaxis

may be utilized in high risk patients such as PROM, obese

patients and prolonged labor.

Keywords: wound infection, caesarean section, risk

factors, post caesarean infection

QATAR MEDICAL JOURNAL

VOL. 2012 / NO. 2 / 2012

26

Risk factors for wound infection after lower segment cesarean section

INTRODUCTION

Wound infection after a caesarean section (CS) increases

maternal morbidity, hospital stay and medical cost. The

rate of wound infection after CS reported in the recent

literature ranges from 3%16% which depends on the

surveillance methods used to identify infections, the

patient population and the use of prophylactic

antibiotics.1 4

Although CS is the most commonly performed surgical

procedure in Obstetric practice worldwide, the

independent risk factors for postoperative CS wound

infection have not been well documented in the

literature. The purpose of this study was to identify the

factors contributing to wound infection following CS

performed in Saudi patients at a tertiary care hospital of

Dammam University, Saudi Arabia.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

The study was carried out between January 1998 and

December 2007 at King Fahad Hospital, Al Khobar which

is the main referral centre in the region. It provides a

complete range of facilities for high risk feto-maternal

and neonatal care.

During the period of study there were 24 435 deliveries

and 2541 lower segment caesarean sections (LSCS)

giving an incidence of 10.4% of this mode of delivery in

the hospital. A case control study of the clinically

relevant independent risk factors for wound infection

after cesarean was undertaken. All the hospital medical

charts of the case patients with wound infection

diagnosed during the post cesarean hospital stay and/or

during an emergency department visit or inpatient

rehospitalization within 30 days of the operation were

reviewed. Criteria used to diagnose wound infection was

as defined in the Centers for Disease Control and

Prevention's National Nosocomial Infections Surveillance

Systems.5 A control group of 340 patients without

wound infection was randomly selected from the

patients who underwent LSCS during the study period.

Routine skin preparation was undertaken with 10%

Providone iodine solution in all the patients. No drain was

used postoperation in any of the patients.

Wound infection was diagnosed if any two of the

following findings were present: wound cellulitis,

purulent discharge from the wound, hematoma and/or

positive culture of the wound swab. Wound swabs

were cultured for both aerobic and anaerobic microorganisms. According to hospital policy, all CS patients

remained hospitalized for 67 days until primary

wound healing had occurred.

Demographic data for each of the patients included age,

parity, body mass index (BMI) on admission, previous

obstetric history including previous CS, booked or no

Al Jama

antenatal care, medical complications in pregnancy such

as diabetes mellitus (DM), chronic hypertension and

renal disease, SLE, gestational age at delivery, prolonged

rupture of membranes (PROM), number of vaginal

examinations in labor prior to CS, duration of labor,

operating time and total blood loss during CS, and use of

antibiotics were noted from each of the patient's medical

record, delivery and operating room records, and hospital

data base.

The epidemiological and obstetric variables were studied

for the patient and control groups. Categorical variables

in the two groups were compared by using X 2 or Fisher

exact test. Continuous variables were compared using

the Student 't' test. These tests were 2-tailed and

p # 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Variables with p , 0.20 in the univariate analysis were

evaluated by multivariate logistic regression noting the

odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) for

independent risk factors. SPSS version 16.0 was used to

perform the statistical analyses. Approval for this study

was obtained from the hospital research and ethical

committee.

RESULTS

Among the 2541 cesarean sections there were 107

(4.2%) instances of wound infection. A total of 2282

(89.8%) were primary CS and 259 (10.2%) repeat CS.

Low transverse CS was most commonly performed

through a pfannenstiel skin incision in both the groups of

patients. Midline, subumbilical incision was performed

in patients with a previous midline scar in 6 (5.6%)

case patients and 11 (3.2%) of the control group. Age

ranged from 20 44 years (mean 31 ^ 3.4 years) and

18 patients were nulliparous in the patient group. The

others were multiparous (from para 18). Age and

parity were not significant factors for wound infection in

the study.

The maternal variables associated with wound infection

after LSCS are shown in Table 1. In the patient group,

23 (21.5%) patients were admitted in labor and seen for

the first time during the pregnancy compared with

34 (10.0%) of the control group. Risk factors which

were statistically significant in the two groups of

patients were obesity (BMI . 30 kg/m2) and unbooked

category of mothers. The numbers of patients with

chorioamnionitis were small, although there was

statistical significance of this variable. Of the 107

infected patients, 76 (71%) underwent emergency

operation and 31 (29%) patients had elective operation

which was not statistically significant. Table 2 shows the

obstetric variables, where duration of labor (.12 hours)

was found to be a significant risk factor associated with

wound infection. No significance was found of PROM

and number of vaginal examinations with wound

QATAR MEDICAL JOURNAL

VOL. 2012 / NO. 2 / 2012

27

Risk factors for wound infection after lower segment cesarean section

Al Jama

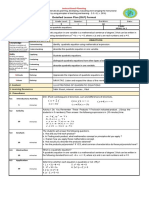

Table 1. Maternal risk factors in the patient and control groups.

Factor

Unbooked patients

Patient group,

n 107 (%)

Control group,

n 340 (%)

OR (95% CI)

p Value

23 (21.5)

34 (10.0)

2.46 (1.374.408)

0.004*

BMI (.30 kg/m )

27 (25.2)

46 (13.5)

2.15 (1.263.673)

0.007*

Diabetes mellitus

12 (11.2)

33 (9.7)

1.17 (0.572.34)

0.713

Failed induction of labor

17 (15.9)

42 (12.4)

1.34 (0.7272.468)

0.3314

9 (8.4)

5 (1.5)

6.15 (2.01518.786)

0.0013*

Elective

31 (29.0)

104 (30.6)

Emergency

76 (71.0)

236 (69.4)

Chorioamnionitis

Type of CS

1.0

1.08 (0.6704-1.741)

0.93

*, significant; BMI, body mass index.

infection, although there was borderline association

between prolonged operating time $1 hour and

excessive blood loss during operation (.1000 ml).

Despite prophylactic antibiotic use in all the patients

who had PROM for more than 8 hours, 10 case patients

developed wound infection (Table 2). This was not found

to be statistically significant.

Independent risk factors for wound infection that were

identified by the multivariate analysis included patients

with no antenatal care, high BMI, duration of labor longer

than 12 hours and operating time more than one hour

(Table 3).

Of the 11 (10.3%) case patients with wound

dehiscence, 4 (3.7%) had burst abdomen with

evisceration that required major repair under general

anesthesia. Two of these had midline, subumbilical and

two patients had a pfannenstiel incision at CS. In

the remaining 7 patients the wound dehiscence

Table 2. Obstetric variables studied in the patient and control groups.

Patient group,

n 107 (%)

Control group,

n 340 (%)

OR (95% CI)

No labor

41 (38.3)

152 (44.7)

1.0

, 6 hrs

12 (11.2)

66 (19.4)

0.67 (0.271.01)

0.272

612 hrs

14 (13.1)

48 (14.1)

1.08 (0.481.72)

0.824

. 12 hrs

40 (37.4)

74 (21.8)

2.00 (1.343.423)

0.008*

None

46 (43.0)

165 (48.5)

1.0

, 8 hrs

51 (47.7)

156 (45.9)

. 8 hrs

10 (9.3)

Variable

p Value

Duration of labor

PROM

1.074 (0.695 1.66)

0.824

19 (5.6)

0.742 (0.78363.871)

0.179

21 (19.6)

84 (24.7)

1.0

#4

68 (53.6)

214 (62.9)

1.026 (0.654 1.611)

0.788

$5

18 (16.8)

42 (12.4)

1.34 (0.727 2.468)

0.255

, 1 hr

71 (66.4)

256 (75.3)

1.0

. 1 hr

36 (33.6)

84 (24.7)

1.54 (0.965 2.47)

0.079

18 (16.8)

35 (10.3)

1.76 (0.953.26)

0.0854

No. vaginal exams

Operation time

Blood loss at CS

. 1000 ml

*, significant.

28 QATAR MEDICAL JOURNAL

VOL. 2012 / NO. 2 / 2012

Risk factors for wound infection after lower segment cesarean section

Al Jama

Table 3. Multivariate analyses of risk factors for wound infection following lower segment

cesarean section.

OR* (95% CI)

Risk factor

p Value

,0.001

Unbooked patients

9.4 (3.4622.38)

BMI at admission (.30 kg/m2)

2.1 (1.722.15)

0.005

PROM . 8 hrs

0.3 (0.21.65)

0.241

0.736 (0.124.54)

0.741

3.2 (1.65.44)

0.003

2.16 (1.424.35)

0.016

0.5 (0.232.16)

0.318

Vaginal exam .4

Duration of labor .12 hours

Operating time .1 hour

Blood loss .1000 ml

*, adjusted odds ratio; BMI, Body mass index; , significant.

(pfannenstiel) was resutured under local analgesia).

Mean postoperative hospital stay was 6 days in the

control group and 10 days in the case patients.

Of the 107 wound swabs cultured 8 (7.5%) cases

showed no bacterial growth. Staph aureus was the

commonest micro-organism found in 50.4% patients

either alone or combined with other organisms (Table 4).

Staph epidermidis was isolated in 21.5%, group B

streptococcus (GBS) in 24% and E.coli in 15.4%

patients. In 44 (41.1%) cases there was a mixed growth

of organisms. There were 7 cases with anaerobic

isolates. Blood culture was performed in 21 patients and

4 of them were positive (GBS 2, E. coli 2).

DISCUSSION

The incidence of wound infection after CS ranges widely

due to a variety of risk factors present in different

patient populations. The mean rate of infection after CS

for hospitals in the USA was reported to be 3.15%.5

A review of the literature revealed much higher rates of

wound infection after CS such as 8.5%,6 16.2%,7 19%,8

and 25.3%9 from other centers. The wound infection

rate (4.2%) after LSCS found in this study correlates well

with 3.7%,10 4.5%,11 and 5%,12 found in recent studies

reported in the literature.

Previous studies identified a number of risk factors

associated with increased rate of wound infection

like younger age group, obesity, DM, chorioamnionitis,

unbooked patients, PROM, emergency delivery,

longer operative time and absence of antibiotic

prophylaxis.2,3,10,13 Age of the patient was not found to

be a risk factor for wound infection, and there was no

significant association between DM and wound infection

in this study which conforms to some studies reported

earlier in the literature.12,14 A possible explanation for

this may be the strict antenatal and preoperative blood

glucose control in the patients.12,14

The wide variation of reported independent risk factors

for wound infection may be due to the selection

variability of potential risk factors for analysis.3 Factors

that significantly increase the risk of wound infection

such as obesity, lack of antenatal care and prolonged

labor found in this study conform with previous

reports.2,10 Increased operating time was also found to

be an independent risk factor which could have resulted

from difficulties encountered in patients with previous

laparotomy or cesarean sections. Surgical expertise of

the operators in the study was overall good and uniform

in keeping with the protocol of a teaching institution.

Obesity is a well known risk factor for wound infection.

The relative avascularity of adipose tissue, increase of

wound area, and the poor penetration of antibiotics in

adipose tissue attribute to this association of risk. A

statistically significant association between higher BMI

on admission and wound infection in the patient group

(mean BMI of 35.3 kg/m2) compared with mean BMI of

31.2 kg/m2 for the control ( p 0.005) was similar to

other reports in the literature.9,11

Some studies have shown significant reduction of

endometritis and total postoperative maternal infectious

Table 4. Microbiological isolates from the wound swab.

Microorganism

Nos.

S. aureus

54

50.4

S. epiderdimis

23

21.5

G-B Streptococcus

26

24.3

E. coli

18

16.8

Proteus mirabilis

7.5

Psuedomonas species

2.8

Klebsiella aerogenes

1.9

Anerobic streptococcus

6.5

p

G-B S group B streptococcus

QATAR MEDICAL JOURNAL

VOL. 2012 / NO. 2 / 2012

29

Risk factors for wound infection after lower segment cesarean section

febrile morbidity rate after CS by the use of prophylactic

antibiotics,15 17 while others did not find such

association.12,18 The Committee on Obstetric Practice

of The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) has recently recommended antimicrobial

prophylaxis for all cesarean deliveries unless the patient

is already receiving appropriate antibiotics (eg, for

chorioamnionitis) and that prophylaxis should be

administered within 60 minutes of the start of the

procedure. When this is not possible (eg, need for

emergent delivery), prophylaxis should be administered

as soon as possible.19 Prophylactic antibiotics were not

routinely used in all CS patients in the present study,

except in those with PROM for more than 8 hours. No

statistically significant association was found in this

study in patients with PROM .8 hours (Table 3).

Al Jama

S. aureus was isolated in 50.5% wound swabs from the

patient group in the study. Strict sterile technique and

wound care in the operating room and in-patient ward

will greatly reduce wound infection due to this organism.

As a result of wound infection the mean hospital stay in

the present study was 4 days longer in the patient group

compared to the control.

Independent high risk factors for wound infection such

as obesity, prolonged labor, and length of surgical

procedure are to be systematically incorporated into

approaches for the prevention and surveillance of

postoperative wound infection. This in turn could help to

identify high risk patients preoperatively, and in the

development of strategies to reduce the incidence of

wound infection.

REFERENCES

1. Chain W, Bashiri A, Bar-David J, Sheham-Yardi I,

Mezor M. Prevalence and clinical significance of

postpartum endometritis and wound infection.

Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol. 2000;8:7782.

2. Tran TS, Jamuditrat S, Chongsuvivatwong V,

Geater A. Risk factors for postcesarean surgical site

infection. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;95:367371.

3. Killian CA, Graffunder EM, Vinciguerra TJ,

Venezia RA. Risk factors for surgical- site infections

following cesarean infection. Infect Control Hosp

Epidemiol. 2001;22:613617.

4. Yokoe DS, Noskin GA, Cunnigham SM, Zuccotti G,

Plaskett T, Fraser VJ, Olsen MA, Tokars JI, Solomon

S, Perl TM, Cosgrove SE, Tilson RS, Greenbaum M,

Hooper DC, Sands KE, Tully J, Herwaldt La,

Diekema DJ, Wong ES, Climo M, Platt R. Enhanced

identification of postoperative infections among

inpatients. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;

10(11):19241930.

5. National Nosocomial Infections Surveillance System. National Nosocomial Infections Surveillance

(NNIS) System Report, data summary from January

1992 through June 2004, issued October 2004.

Am J Infect Control. 2004;32:470485.

at the University College Hospital Ibadan, Nigeria.

Niger J Clin Pract. 2009;2(1):15.

8. Koigi-Kamau R, Kabare LW, Wanyoke-Gichuhi J.

Incidence of wound infection after caesarean

delivery in a district hospital in central Kenya. East

Afr Med J. 2005;82(7):357361.

9. Beattie PG, Rings TR, Hunter MF, Lake Y. Risk

factors for wound infection following caesarean

section. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 1994;

34(4):398402.

10. Schneid-Kofman N, Sheiner E, Levy A, Holcberg G.

Risk factors for wound infection following cesarean

deliveries. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2005;90:1015.

11. Habib F. Incidence of post cesarean section wound

infection in a tertiary hospital, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Saudi Med J. 2002;23(9):1059 1063.

12. Olsen MA, Butler AM, Willers DM, Devkota P,

Gross GA, Fraser VJ. Risk factors for surgical site

infection after low transverse cesarean section.

Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2006;29

(6):447484.

13. Johnson A, Young D, Reilly J. Caesarean section

surgical site infection surveillance. J Hosp Infect.

2006;64:3035.

6. Opoien HK, Valba A, Grinde-Anderson A, Walberg

M. Post-cesarean section surgical site infections

according to CDC standards: rates and risk factors.

A prospective cohort study. Acta Obstet Gynecol

Scand. 2007;86(9):1097 1102.

14. Zerr KJ, Furnary AF, Grunkemeier Gl, Bookin S,

Kanhere V, Starr A. Glucose control lowers the risk

of wound infection in diabetics after open heart

operations. Ann Thorac Surg. 1997;63:356361.

7. Morhason-Bello IO, Oladokun A, Adedokun BO,

Obisesan KA, Ojengbede OA, Okuyemi OO, Niger J.

Determinants of post-caesarean wound infection

15. Thigpen BD, Hood WA, Chauhan S, Bufkin L, Bofill J,

Magann E, Morrison JC. Timing of prophylactic

antibiotic administration in the uninfected laboring

30 QATAR MEDICAL JOURNAL

VOL. 2012 / NO. 2 / 2012

Risk factors for wound infection after lower segment cesarean section

gravida: a randomized clinical trial. Am J Obstet

Gynecol. 2005;192:18641868; discussion

18681871.

16. Sullivan SA, Smith T, Chang E, Hulsey T, Vandorsten

JP, Soper D. Administration of cefazolin prior to skin

incision is superior to cefazolin at cord clamping in

preventing post-cesarean infectious morbidity: a

randomized, controlled trial [published erratum

appears in Am J Obstet Gynecol 2007; 197:333].

Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;196:455.e1455.e5.

17. Smaill FM, Gyte GM. Antibiotic prophylaxis versus

no prophylaxis for preventing infection after

Al Jama

cesarean section. Cochrane Database Syst Rev.

2010; (1):CD007482. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.

CD007482. pub 2.

18. Krentner A, Del Bene V, Delamar D, Huguley V,

Harnon P, Mitchell K. Peri-operative antibiotics

prophylaxis in caesarean section. Obstet Gyecol.

1978;52:279284.

19. Committee ACOG. Opinion practice bulletin

number 465. Antimicrobial prophylaxis for

cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;

116(3):791792.

QATAR MEDICAL JOURNAL

VOL. 2012 / NO. 2 / 2012

31

You might also like

- Gynecology and Minimally Invasive Therapy: Case ReportDocument5 pagesGynecology and Minimally Invasive Therapy: Case ReportelenNo ratings yet

- A Review Leptin Structure and Mechanism Actions"Document8 pagesA Review Leptin Structure and Mechanism Actions"elenNo ratings yet

- 03 Bartholin Gland Procedure + Inform ConsentDocument4 pages03 Bartholin Gland Procedure + Inform ConsentelenNo ratings yet

- Drainage of Bartholin Cyst Abscess ML46071Document4 pagesDrainage of Bartholin Cyst Abscess ML46071elenNo ratings yet

- Novel Technique For Management of Bartholin Gland CystsnDocument3 pagesNovel Technique For Management of Bartholin Gland CystsnelenNo ratings yet

- Thyroid Autoimmunity and Female Infertility: Kris Poppe, Daniel Glinoer, Brigitte VelkeniersDocument16 pagesThyroid Autoimmunity and Female Infertility: Kris Poppe, Daniel Glinoer, Brigitte VelkenierselenNo ratings yet

- Alo AjogDocument1 pageAlo AjogelenNo ratings yet

- Best Practice in Comprehensive Abortion Care RCOGDocument17 pagesBest Practice in Comprehensive Abortion Care RCOGelenNo ratings yet

- Severe Preeclampsia BahanDocument7 pagesSevere Preeclampsia BahanelenNo ratings yet

- 294 Fetal Heart Rate Monitoring. Principles and Interpretation of Cardiotocography LR PDFDocument9 pages294 Fetal Heart Rate Monitoring. Principles and Interpretation of Cardiotocography LR PDFelenNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- 01 - Measures of Disease OccurrenceDocument16 pages01 - Measures of Disease OccurrenceSaad MotawéaNo ratings yet

- The Logic of Faith Vol. 1Document39 pagesThe Logic of Faith Vol. 1Domenic Marbaniang100% (2)

- US6362718 Meg Tom Bearden 1Document15 pagesUS6362718 Meg Tom Bearden 1Mihai DanielNo ratings yet

- Jib Cranes 20875644 Colour CatalogueDocument30 pagesJib Cranes 20875644 Colour Cataloguepsingh1996No ratings yet

- MD Boiler Asme WTDocument159 pagesMD Boiler Asme WTdodikNo ratings yet

- Rollercoaster Web Quest WorksheetDocument3 pagesRollercoaster Web Quest WorksheetDaniel Toberman0% (1)

- MyLabX8 160000166 V02 LowRes PDFDocument8 pagesMyLabX8 160000166 V02 LowRes PDFhery_targerNo ratings yet

- Christie Roadster S+20K Serial CommunicationsDocument87 pagesChristie Roadster S+20K Serial Communicationst_wexNo ratings yet

- Catálogo Greenleaf PDFDocument52 pagesCatálogo Greenleaf PDFAnonymous TqRycNChNo ratings yet

- Group 15 - The Elements NitrogenDocument19 pagesGroup 15 - The Elements NitrogenHarold Isai Silvestre GomezNo ratings yet

- Siesta TutorialDocument14 pagesSiesta TutorialCharles Marcotte GirardNo ratings yet

- 3tnv82a Bdsa2Document2 pages3tnv82a Bdsa2BaggerkingNo ratings yet

- LVS x00 DatasheetDocument3 pagesLVS x00 DatasheetEmanuel CondeNo ratings yet

- A Tale of Two Cultures: Contrasting Quantitative and Qualitative Research - Mahoney e GoertzDocument24 pagesA Tale of Two Cultures: Contrasting Quantitative and Qualitative Research - Mahoney e Goertzandre_eiras2057No ratings yet

- Ma103 NotesDocument110 pagesMa103 NotesginlerNo ratings yet

- Mathematics Item Specification: Grade 8Document9 pagesMathematics Item Specification: Grade 8Hoàng Nguyễn Tuấn PhươngNo ratings yet

- GenMath11 Q1 Mod5 KDoctoleroDocument28 pagesGenMath11 Q1 Mod5 KDoctoleroNicoleNo ratings yet

- DYA Series 2018Document22 pagesDYA Series 2018Abo MohammedNo ratings yet

- Cuda GDBDocument64 pagesCuda GDBVinícius LisboaNo ratings yet

- Franks 2009Document11 pagesFranks 2009bhanu0% (1)

- Motion 2000 Hydraulic v8 42-02-1P20 B7Document248 pagesMotion 2000 Hydraulic v8 42-02-1P20 B7ElputoAmo XD100% (1)

- Delta ASDA B User ManualDocument321 pagesDelta ASDA B User ManualRichard ThainkhaNo ratings yet

- Tactical Missile Design Presentation FleemanDocument422 pagesTactical Missile Design Presentation Fleemanfarhadi100% (16)

- Cec l-109-14Document5 pagesCec l-109-14metaNo ratings yet

- Educ 75 Activity 7Document3 pagesEduc 75 Activity 7Gliecy OletaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 4-The Simple Interest 2Document121 pagesChapter 4-The Simple Interest 2course heroNo ratings yet

- Detailed Lesson Plan (DLP) Format: Nowledge ObjectivesDocument2 pagesDetailed Lesson Plan (DLP) Format: Nowledge ObjectivesErwin B. NavarroNo ratings yet

- Automatic Power Factor Detection and CorDocument53 pagesAutomatic Power Factor Detection and CorAshritaNo ratings yet

- Cert Piping W54.5Document2 pagesCert Piping W54.5SANU0% (1)

- Powernel1500 TDS EN 02152006Document1 pagePowernel1500 TDS EN 02152006Magoge NgoashengNo ratings yet