Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Tian Et Al. (Auths.) - Effects of Circumcision On Male Sexual Functions

Uploaded by

Omar MohammedOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Tian Et Al. (Auths.) - Effects of Circumcision On Male Sexual Functions

Uploaded by

Omar MohammedCopyright:

Available Formats

Asian Journal of Andrology (2013) 15, 662666

2013 AJA, SIMM & SJTU. All rights reserved 1008-682X/13 $32.00

www.nature.com/aja

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Effects of circumcision on male sexual functions:

a systematic review and meta-analysis

Ye Tian1,*, Wei Liu2,*, Jian-Zhong Wang1, Romel Wazir1, Xuan Yue1 and Kun-Jie Wang1

This meta-analysis was performed to assess sexual functions following adult male circumcision. We searched the Cochrane Central

Register of Controlled Trials, PUBMED, EMBASE, the Cochrane Database of Systematic Review and Web of Science from their

inception until January 2013 to identify all eligible studies that reported on mens sexual function after circumcision. The Cochrane

Collaborations RevMan 5.2 software was employed for data analysis, and the fixed or the random effect model was selected depending

on the proportion of heterogeneity. We identified 10 studies, which described a total of 9317 circumcised and 9423 uncircumcised

men who were evaluated for the association of circumcision with male sexual function. There were no significant differences in sexual

desire (odds ratio (OR): 0.99; 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.921.06), dyspareunia (OR: 1.12; 95% CI: 0.522.44), premature

ejaculation (OR: 1.13; 95% CI: 0.831.54), ejaculation latency time (OR: 1.33; 95% CI: 0.691.97), erectile dysfunctions (OR:

0.90; 95% CI: 0.651.25) and orgasm difficulties (OR: 0.97; 95% CI: 0.831.13). These findings suggest that circumcision is

unlikely to adversely affect male sexual functions. However, these results should be evaluated in light of the low quality of the existing

evidence and the significant heterogeneity across the various studies. Well-designed and prospective studies are required for a further

understanding of this topic.

Asian Journal of Andrology (2013) 15, 662666; doi:10.1038/aja.2013.47; published online 10 June 2013

Keywords: complications; male circumcision; review; sexual function

INTRODUCTION

Male circumcision is one of the most commonly performed surgical

procedures in the world. Globally, an estimated one-third of males are

circumcised for religious, cultural, medical, personal preference and

several other reasons.1 Circumcision is generally considered as a simple, rapid operation with efficacy for protection against HIV and other

sexually transmitted infections, as confirmed in numerous, highquality studies.27 Circumcision has been reported to adversely affect

sexual function;8 however, the majority of studies, including highquality ones911 and ones with data arising from randomized controlled trials (RCTs),12,13 show no difference or improvement in sexual function, sensitivity and satisfaction after circumcision. All of the

data were considered by the American Academy of Pediatrics in formulating its 2012 policy, which concluded that there were no adverse

effects on these parameters.14 Speculative assertions that the removal

of fine-touch neuroreceptors of the foreskin, reorganization/atrophy

of neural circuitry and keratinisation of the glans penis as a result of

circumcision might lower sensitivity and lead to sexual dysfunction8,1517 have been refuted by the American Academy of Pediatrics

and through evaluations by experts of such reports.14,1822

Across cultural, religious and health-related differences around the

world, the pleasures of sexual intimacy and orgasm are ubiquitously

considered as important for well-being and health, and sexual

dysfunction may give rise to lowered self-esteem and dysfunctional

relationships.23,24 In this context, we attempted to perform a systematic review and meta-analysis of the comparative effectiveness of circumcised and uncircumcised men on their sexual functions, including

sexual desire, dyspareunia, premature ejaculation (PE), ejaculation

latency time and erectile dysfunctions (EDs), by collecting all published relevant studies to provide a comprehensive survey that

addresses this controversy.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data sources and search strategy

We searched the PUBMED, EMBASE, the Cochrane Database of

Systematic Review and Web of Science from their inception until

January 2013. The search terms used to identify potentially eligible

studies from each data source were as follows: circumcision, male;

circumcision; sexual dysfunction; ejaculation; dyspareunia; sexual desire; orgasm; and erection. We also searched the reference

lists of the relevant studies. Two of our authors independently

screened all citations and abstracts identified by the search strategy

used to screen eligible studies. Articles in other languages were also

sought and evaluated.

Study outcomes

The primary outcomes in our work were PE and ED, and the secondary outcomes were low or lack of sexual desire, dyspareunia and

1

Department of Urology, West China Hospital, Sichuan University, Chengdu 610041, China and 2Department of Cardiology, West China Hospital, Sichuan University, Chengdu

610041, China

* These authors contributed equally to this work and should be considered as co-first authors.

Correspondence: Dr KJ Wang (wangkunjie@gmail.com)

Received: 27 January 2013; Revised: 23 February 2013; Accepted: 27 March 2013; Published online: 10 June 2013

Circumcision and male sexual functions

Y Tian et al

663

Data synthesis and analysis

Primary and secondary outcomes were calculated from the estimates

of each study to enumerate pooled odds ratios (ORs) and confidence

intervals (CIs). The Review Manager 5.2 software (The Cochrane

Collaboration, Oxford, UK) statistical package was used to analyse

the ORs for dichotomous variables and the mean differences for continuous variables. Meta-analyses were performed using this software

to determine the ORs and CIs of men for the following criteria: PE, ED,

dyspareunia, orgasm difficulties, and low or lack of sexual desire. The

MantelHaenszel-type method was used to estimate the pooled ORs

for all strata. The proportion of heterogeneity across the studies was

tested using the I2 index (range: 0%100%). If I2f50%, the variation

of the studies was considered to be homogenous and the fixed-effect

model was adopted. If I2.50%, the variation of studies was considered

as significantly heterogeneous and the random-effect model was

adopted. All P values were two-tailed, and a,0.05 was considered

statistically significant (P,0.05).

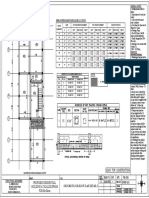

Figure 1 Flow diagram for selection of studies.

orgasm difficulties. Because there is no agreement as to what constitutes PE, the quantifiable and objective outcome thrust times between

penetration and ejaculation, namely, the intravaginal ejaculation

latency time (IELT), were also analysed from the included studies.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Only studies that compared sexual functions with male circumcision

status were included. All relevant studies identified from the search

strategy were used for detailed assessment. Studies with insufficient

data were not included due to potential statistical analysis limitations.

Additionally, studies among men who had sex with other men were

excluded because the sexual function criteria were unclear for such

evaluations. Data were independently extracted from the included

studies by two investigators. Discrepancies for study inclusion

between the investigators were resolved by discussions or further consultations with a third investigator. The extracted data included data

sources, eligibility, methods, participant characteristics, interventions

and results. The quality of these eligible citations was assessed using the

Newcastle-Ottawa Scale, which was independently scored by two

investigators.

RESULTS

Data retrieval

A total of 183 studies met the inclusion criteria on the basis of our

search strategy and relevant references. Upon the completion of primary screenings by scanning titles and abstracts, the full texts of 19

potentially relevant studies were obtained for the secondary screenings. We excluded nine studies because of insufficient or duplicated

data, or because they described female circumcision. Thus, 10 studies

were identified as eligible for this systematic review, including a total of

18 740 participants (including self-controlled studies), of whom 9317

(49.72%) were circumcised (Figure 1).

Study characteristics

Ten studies were included in our analysis (Table 1), which most relied

on retrospective institutional data from casecontrol studies or on

cross-sectional designs; however, two relatively well-designed studies

were also eligible. Participants from these studies were relatively well

represented, including Caucasian, Black African and Asian. The 10

studies selected for this meta-analysis described sexual-function criteria, including five with PE, six with ED, five with dyspareunia, four

with orgasm difficulties, four with low or absent sexual desire and

three with IELT. Nine of the eligible studies were published in

English, and one was published in Chinese.

PE and ejaculation latency time

PE data were available from five of the included studies, and three

studies provided data on IELT. The difference in PE incidence between

Table 1 Characteristics of the eligible studies

Study source

Frisch et al. (2011)17

Waldinger et al. (2009)25

Krieger et al. (2008)13

Senol et al. (2008)26

Kigozi et al. (2008)12

Richters et al. (2006)27

Masood et al. (2005)28

Senkul et al. (2004)29

Shen et al. (2004)30

Laumann et al. (1997)9

Country

Denmark

Netherlands, Spain, United Kingdom

and the United States

Kenya

Turkey

Uganda

Australia

United Kingdom

Turkey

China

United States

Age (average

(range)), year

38.5(/)

23.4 (1827)

(1549)

(1659)

(1860)

22.3 (1928)

33.2 (2251)

(1859)

Study design

Duration

Study size

NOS score

(max: 9)

Casecontrol study

Casecontrol study

4 weeks

2345

347

6

5

Randomized, controlled trial

Self-controlled trial

Randomized, controlled trial

Casecontrol study

Self-controlled trial

Self-controlled trial

Self-controlled trial

Casecontrol study

24 months

12 weeks

24 months

o3 months

o12 weeks

12 months

2784

43

4456

7060

84

42

95

1221

Abbreviation: NOS, Newcastle-Ottawa Scale.

Asian Journal of Andrology

Circumcision and male sexual functions

Y Tian et al

664

Figure 2 PE in circumcised and uncircumcised men. PE, premature ejaculation.

the circumcised and uncircumcised groups was not significant (OR:

1.13; 95% CI: 0.831.54) (Figure 2). In agreement with the PE data,

the IELT between the circumcised and control groups demonstrated

no significant difference (OR: 1.33; 95% CI: 0.691.97) (Figure 3).

ED

Morbidities of ED or trouble keeping an erection in both the circumcised and uncircumcised group were presented in six of the included

studies. Although the incidence of ED was variable between different

studies, there was no significant difference in ED between the circumcised and uncircumcised groups (OR: 0.90; 95% CI: 0.651.25)

(Figure 4).

Low or absent sexual desire

Three of the four studies that provided clear data were casecontrol

studies. The prevalence of low or lack of sexual desire across the studies

was generally low, and heterogeneity between the studies was minimal.

There was no difference between the prevalence of low or reduced

sexual desire (OR: 0.99; 95% CI: 0.921.06) (Figure 5).

Dyspareunia and orgasm difficulties

Dyspareunia is defined as pain during or after sex and is more often

observed in women than in men. In our meta-analysis, five included

studies that focused on this issue. Like the other outcomes, no significant differences between the circumcised and control groups were

Figure 3 Ejaculation latency time in circumcised and uncircumcised men.

Figure 4 ED in circumcised and uncircumcised men. ED, erectile dysfunction.

Asian Journal of Andrology

observed (OR: 1.12; 95% CI: 0.522.44) (Figure 6). In the circumcised

and uncircumcised groups, orgasm difficulties and the inability to

ejaculate were examined in four studies. There were no statistically

significant differences between the circumcised and the control groups

(OR: 0.97; 95% CI: 0.831.13) (Figure 7).

DISCUSSION

Male circumcision has been performed for over 15 000 years and is

practiced in almost all countries around the world. There is widespread belief that circumcision provides improved penile hygiene

and protects against urinary tract infections, phimosis, paraphimosis,

balanoposthitis, venereal diseases and cancer.5,14,18,22,31,32 It is claimed

that the foreskin has important functions,32 but this has been disputed

by lots of studies.14,1822 The existing evidence from casecontrol,

cross-sectional, cohort and RCT studies were analysed in our systematic review to ascertain pooled estimates of the sexual-function consequences of male circumcision. Overall, the results revealed no

significant differences between circumcised and uncircumcised men

regarding PE, IELT, ED, low or absent sexual desire, orgasm difficulties and dyspareunia.

Male sexual dysfunction has been considered as a neurobiological

phenomenon or a psychological disturbance. The prepuce is a simple

fold of skin composed of an outer keratinized (skin) and inner (mucosal) layers that are rich in nerves. Theoretically, partial or total surgical

removal of the prepuce leaves the somatic penis sensory fibres exposed

Circumcision and male sexual functions

Y Tian et al

665

Figure 5 Low or lacking sexual desire in circumcised and uncircumcised men.

to direct stimulation and in theory could benefit sexual function. A

cross-sectional study of Korean men reported decreased masturbatory

pleasure after undergoing adult circumcision,33 although numerous

flaws in this study have been identified.34

Although there is no universally accepted definition, PE is regarded

as the most common sexual dysfunction in most countries.35 No

significant difference was obtained based on the conflicting studies

regarding the effect of male circumcision on PE and ejaculation

latency time. This result is in agreement with a report by Hosseini

et al.36 that described the post-circumcision, mucosal cuff length as

not being a PE risk factor. Additionally, a recent study of Senel et al.37

that examined the long-term effects of circumcision on sexual function concluded that circumcision did not adversely affect sexual functions, but it caused a significant improvement in erectile function and

overall sexual satisfaction. Similarly, in our work, we found that male

circumcision did not adversely affect ED. Although the international

index of erectile function is the most commonly used method for

evaluating ED, the participants self-reported erection status was

mainly used to measure the outcome in most studies. The ability to

achieve an orgasm is a major determinant of sexual and marital

satisfaction. We obtained no evidence that this differed between

the circumcised and uncircumcised groups. Nonetheless, decisionmaking should be made in accordance with the differences of PE

evaluation and significant heterogeneity across the included studies.

Of the 10 studies included, only two involved data arising from

large, well-designed RCTs and provided high-quality, epidemiological

evidence. Most of the studies included in this meta-analysis are less

rigorous in design and not very homogeneous, as they differ in their

study populations. The recent manuscript by Frisch et al.17 focused on

the association of circumcision status with subjective criteria, such as

sexual experiences and difficulties with sexual desire, needs fulfilment

and functioning, rather than objective parameters, such as PE, ejaculation latency time and ED. The authors concluded that circumcision

was associated with frequent orgasm difficulties in Danish men.

Waldinger et al.25 sought to investigate the intravaginal ejaculation

latency time distribution in the general male population from different

countries. This study included a non-selected sample of 474 men

from The Netherlands, Spain, the United Kingdom, Turkey, and the

United States. Senol et al.26 used a different study design that was based

on the assessment of the participants pudendal-evoked potential

rather than utilizing a questionnaire.

The study of Richters et al.27 examined the effects of circumcision

on the sexual health of 10 173 enrolled men but provided no evidence

regarding the effects on sexual sensitivity. Conversely, Masood et al.28

reported a 38% improvement in penile sensation after circumcision.

An overall 61% satisfaction rate was considered as a poor outcome of

circumcision. In the study by Senkul et al.,29 the study group consisted

of 42 male patients with a median age of 22.3 years, whose sexual

performance was evaluated using the Brief Male Sexual Function

Inventory and the ejaculatory latency time before and after circumcision. This report claimed an increase in the ejaculatory latency time

after circumcision. The study by Shen et al.30 reported mild or moderate erectile dysfunction after circumcision, while Laumann et al.9

suggested that circumcised men engaged in more elaborate sets of

sexual practices. However, this pattern differed across ethnic groups

and suggests the influence of social factors.

Increased participant losses during follow-ups in several studies

may adversely affect the findings as a result of non-response

bias.12,13,28 The relatively short, post-circumcision follow-up period

may not accurately reflect sexual function at a later time, resulting in

risk of bias for this meta-analysis.26,28,29 Furthermore, the study

validity may be affected by several factors, including subjective selfreporting, lack of physiological or laboratory indicators of sexual dysfunction or consensus on what constitutes sexual dysfunction for

individuals with different education levels, cultures and religions.

Moreover, operative methods, participants ages and any coexisting

medical conditions were not analysed by subgroup, and these could

also contribute to study bias. Furthermore, well-designed trials seeking to minimize bias should be performed. Nevertheless, the data

provided here affirm that the majority of published research arises

from good to excellent studies on sexual function and sensitivity

following circumcision. Because policy-makers have emphasized that

Figure 6 Dyspareunia in circumcised and uncircumcised men.

Asian Journal of Andrology

Circumcision and male sexual functions

Y Tian et al

666

Figure 7 Orgasm difficulties in circumcised and uncircumcised men.

infancy is the optimum time for circumcision for a variety of reasons,14,18,22 our findings should provide reassurance to parents when

considering this procedure for their newborn sons.

CONCLUSION

In summary, male circumcision does not appear to adversely affect

penile sexual function or sensitivity when compared with uncircumcised men. Although the literature contains a wide range of evidence

for and against circumcision, the better quality studies affirm the

recommendations of reputable experts who have evaluated the benefits and risks of circumcision as a desirable intervention early in

life.14,18,22

Regardless of the present study outcome that shows an absence of

adverse circumcision effects on a range of parameters related to sexual

function and penile sensitivity, there is scope for further research,

especially additional large, well-designed RCTs in diverse settings

and over much longer time periods.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

YT and KJW conceived the review. YT, WL and XY carried out the

search, study selection and data extraction. YT, RW and JZW drafted

the manuscript. KJW, WL and JZW participated in critical revision of

the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

COMPETING FINANCIAL INTERESTS

None of the authors have any conflicts of interests related to this study.

Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) and World Health

Organization (WHO). Male circumcision: global trends and determinants of

prevalence, safety and acceptability. Geneva: UNAIDS/WHO; 2007.

2

Wawer MJ, Tobian AA, Kigozi G, Kong X, Gravitt PE et al. Effect of circumcision of HIVnegative men on transmission of human papillomavirus to HIV-negative women: a

randomised trial in Rakai, Uganda. Lancet 2011; 377: 20918.

3

Bailey RC, Moses S, Parker CB, Agot K, Maclean I et al. Male circumcision for HIV

prevention in young men in Kisumu, Kenya: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet

2007; 369: 64356.

4

Gray RH, Kigozi G, Serwadda D, Makumbi F, Watya S et al. Male circumcision for HIV

prevention in men in Rakai, Uganda: a randomised trial. Lancet 2007; 369: 65766.

5

Morris BJ, Mindel A, Tobian AA, Hankins CA, Gray RH et al. Should male circumcision

be advocated for genital cancer prevention? Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2012; 13: 4839

42.

6

Castellsague X, Bosch FX, Munoz N, Meijer CJ, Shah KV et al. Male circumcision,

penile human papillomavirus infection, and cervical cancer in female partners. N Engl

J Med 2002; 346: 110512.

7

Morris BJ, Wiswell TE. Circumcision and lifetime risk of urinary tract infection: a

systematic review and meta-analysis. J Urol 2012; pii: S0022-5347(12)05623-6.

8

Taylor JR, Lockwood AP, Taylor AJ. The prepuce: specialized mucosa of the penis and

its loss to circumcision. Br J Urol 1996; 77: 2915.

9

Laumann EO, Masi CM, Zuckerman EW. Circumcision in the United States.

Prevalence, prophylactic effects, and sexual practice. JAMA 1997; 277: 10527.

10 Fink KS, Carson CC, DeVellis RF. Adult circumcision outcomes study: effect on

erectile function, penile sensitivity, sexual activity and satisfaction. J Urol 2002;

167: 21136.

Asian Journal of Andrology

11 Payne K, Thaler L, Kukkonen T, Carrier S, Binik Y. Sensation and sexual arousal in

circumcised and uncircumcised men. J Sex Med 2007; 4: 66774.

12 Kigozi G, Watya S, Polis CB, Buwembo D, Kiggundu V et al. The effect of male

circumcision on sexual satisfaction and function, results from a randomized trial of

male circumcision for human immunodeficiency virus prevention, Rakai, Uganda.

BJU Int 2008; 101: 6570.

13 Krieger JN, Mehta SD, Bailey RC, Agot K, Ndinya-Achola JO et al. Adult male

circumcision: effects on sexual function and sexual satisfaction in Kisumu, Kenya.

J Sex Med 2008; 5: 261022.

14 American Academy of Pediatrics Task Force on Circumcision. Circumcision policy

statement. Pediatrics 2012; 130: 5856.

15 Immerman RS, Mackey WC. A proposed relationship between circumcision and neural

reorganization. J Genet Psychol 1998; 159: 36778.

16 Sorrells ML, Snyder JL, Reiss MD, Eden C, Milos MF et al. Fine-touch pressure

thresholds in the adult penis. BJU Int 2007; 99: 8649.

17 Frisch M, Lindholm M, Gronbaek M. Male circumcision and sexual function in men

and women: a survey-based, cross-sectional study in Denmark. Int J Epidemiol 2011;

40: 136781.

18 Morris BJ, Wodak AD, Mindel A, Schrieber L, Duggan KA et al. Infant male

circumcision: An evidence-based policy statement. Open J Prev Med 2012; 2: 7992.

19 Waskett JH, Morris BJ. Fine-touch pressure thresholds in the adult penis. BJU Int

2007; 99: 15512.

20 Morris BJ, Waskett JH, Gray RH. Does sexual function survey in Denmark offer any

support for male circumcision having an adverse effect? Int J Epidemiol 2012; 41:

3102, 3124.

21 Morris BJ, Waskett JH, Bollinger D, van Howe R. Claims that circumcision increases

alexithymia and erectile dysfunction are unfounded: a critique of Bollinger and Van

Howes Alexthymia and circumcision trauma: a preliminary investigation. Int J Mens

Health 2012; 11: 17784.

22 Morris BJ, Waskett JH, Banerjee J, Wamai RG, Tobian AA et al. A snip in time: what is

the best age to circumcise? BMC Pediatr 2012; 12: 20.

23 Symonds T, Roblin D, Hart K, Althof S. How does premature ejaculation impact a man

s life? J Sex Marital Ther 2003; 29: 36170.

24 Althof SE. Psychological treatment strategies for rapid ejaculation: rationale, practical

aspects, and outcome. World J Urol 2005; 23: 8992.

25 Waldinger MD, McIntosh J, Schweitzer DH. A five-nation survey to assess the

distribution of the intravaginal ejaculatory latency time among the general male

population. J Sex Med 2009; 6: 288895.

26 Senol MG, Sen B, Karademir K, Sen H, Saracoglu M. The effect of male circumcision

on pudendal evoked potentials and sexual satisfaction. Acta Neurol Belg 2008; 108:

903.

27 Richters J, Smith AM, de Visser RO, Grulich AE, Rissel CE. Circumcision in Australia:

prevalence and effects on sexual health. Int J STD AIDS 2006; 17: 54754.

28 Masood S, Patel HR, Himpson RC, Palmer JH, Mufti GR et al. Penile sensitivity and

sexual satisfaction after circumcision: are we informing men correctly? Urol Int 2005;

75: 626.

29 Senkul T, IserI C, Sen B, KarademIr K, Saracoglu F et al. Circumcision in adults: effect

on sexual function. Urology 2004; 63: 1558.

30 Shen Z, Chen S, Zhu C, Wan Q, Chen Z. Erectile function evaluation after adult

circumcision. Zhonghua Nan Ke Xue 2004; 10: 189. Chineses.

31 Siegfried N, Muller M, Deeks JJ, Volmink J. Male circumcision for prevention of

heterosexual acquisition of HIV in men. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009; (2):

CD003362.

32 Morris BJ, Gray RH, Castellsague X, Bosch FX, Halperin DT et al. The strong protective

effect of circumcision against cancer of the penis. Adv Urol 2011; 2011: 812368.

33 Kim D, Pang MG. The effect of male circumcision on sexuality. BJU Int 2007; 99:

61922.

34 Willcourt R. The effect of male circumcision on sexuality. BJU Int 2007; 99: 1169

70.

35 Wylie KR, Ralph D. Premature ejaculation: the current literature. Curr Opin Urol 2005;

15: 3938.

36 Hosseini SR, Khazaeli MH, Atharikia D. Role of postcircumcision mucosal cuff length

in lifelong premature ejaculation: a pilot study. J Sex Med 2008; 5: 2069.

37 Senel FM, Demirelli M, Misirlioglu F, Sezgin T. Adult male circumcision performed

with plastic clamp technique in Turkey: results and long-term effects on sexual

function. Urol J 2012; 9: 7005.

You might also like

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- O'Hara & O'Hara - The Effect of Male Circumcision On The Sexual Enjoyment of The Female Partner PDFDocument6 pagesO'Hara & O'Hara - The Effect of Male Circumcision On The Sexual Enjoyment of The Female Partner PDFOmar MohammedNo ratings yet

- Erich FrommDocument2 pagesErich FrommTina NavarroNo ratings yet

- The Origins of Adīth: A Critical Appraisal of A Western Approach To The SubjectDocument412 pagesThe Origins of Adīth: A Critical Appraisal of A Western Approach To The SubjectOmar MohammedNo ratings yet

- Data Management For Human Resource Information SystemDocument14 pagesData Management For Human Resource Information SystemRajeshsharmapurangNo ratings yet

- Al-Azmeh (1981) - The Articulation of OrientalismDocument20 pagesAl-Azmeh (1981) - The Articulation of OrientalismOmar MohammedNo ratings yet

- NSTP1 MODULE 3 Disaster Awareness Preparedness and ManagementDocument16 pagesNSTP1 MODULE 3 Disaster Awareness Preparedness and Managementrenz dave100% (2)

- Whelan - Forgotten WitnessDocument15 pagesWhelan - Forgotten WitnessOmar MohammedNo ratings yet

- Harald Motzki (2002) - The Biography of MuhammadDocument175 pagesHarald Motzki (2002) - The Biography of MuhammadOmar MohammedNo ratings yet

- A Scholar in The DesertDocument4 pagesA Scholar in The DesertOmar MohammedNo ratings yet

- Abbott & Byrd - Practical Advice For Parents Who Want To Encourage HeterosexualityDocument24 pagesAbbott & Byrd - Practical Advice For Parents Who Want To Encourage HeterosexualityOmar MohammedNo ratings yet

- Fink, Carson & DeVellis - Adult Circumcision Outcomes Study PDFDocument4 pagesFink, Carson & DeVellis - Adult Circumcision Outcomes Study PDFOmar MohammedNo ratings yet

- Bossio, Pukall & Steele (2015) - Examining Penile Sensitivity in Neonatally Circumcised and Intact Men Using Quantitative Sensory TestingDocument19 pagesBossio, Pukall & Steele (2015) - Examining Penile Sensitivity in Neonatally Circumcised and Intact Men Using Quantitative Sensory TestingOmar MohammedNo ratings yet

- Quantum Cosmology and The Initial State of The UniverseDocument10 pagesQuantum Cosmology and The Initial State of The UniverseOmar MohammedNo ratings yet

- Morris & Krieger - Male Circumcision Does Not Reduce Sexual Function, Sensitivity, or SatisfactionDocument8 pagesMorris & Krieger - Male Circumcision Does Not Reduce Sexual Function, Sensitivity, or SatisfactionOmar MohammedNo ratings yet

- Al-Ghabbān - The Evolution of The Arabic Script in The Period of The Prophet Mu Ammad and The Orthodox Caliphs in The Light of New Inscriptions Discovered in The Kingdom of Saudi ArabiaDocument14 pagesAl-Ghabbān - The Evolution of The Arabic Script in The Period of The Prophet Mu Ammad and The Orthodox Caliphs in The Light of New Inscriptions Discovered in The Kingdom of Saudi ArabiaOmar MohammedNo ratings yet

- Premarital Sex and The Risk of DivorceDocument12 pagesPremarital Sex and The Risk of DivorceOmar MohammedNo ratings yet

- The Common Link and Its Relation To The MadārDocument37 pagesThe Common Link and Its Relation To The MadārOmar MohammedNo ratings yet

- Creation of Universes From NothingDocument4 pagesCreation of Universes From NothingOmar MohammedNo ratings yet

- Yūsuf Al - Uyairī and The Making of A Revolutionary Salafi PraxisDocument39 pagesYūsuf Al - Uyairī and The Making of A Revolutionary Salafi PraxisOmar MohammedNo ratings yet

- The Ultimate PunishmentDocument11 pagesThe Ultimate PunishmentOmar MohammedNo ratings yet

- In Defense of The Death PenaltyDocument15 pagesIn Defense of The Death PenaltyOmar MohammedNo ratings yet

- Is Capital Punishment Morally RequiredDocument53 pagesIs Capital Punishment Morally RequiredOmar MohammedNo ratings yet

- The Case Against The Case Against The Death PenaltyDocument27 pagesThe Case Against The Case Against The Death PenaltyOmar MohammedNo ratings yet

- Edgie A. Tenerife BSHM 1108: Page 1 of 4Document4 pagesEdgie A. Tenerife BSHM 1108: Page 1 of 4Edgie TenerifeNo ratings yet

- Drug Development: New Chemical Entity DevelopmentDocument6 pagesDrug Development: New Chemical Entity DevelopmentDeenNo ratings yet

- Imagine Unit 1 P 10 11Document1 pageImagine Unit 1 P 10 11נויה לבדובNo ratings yet

- Citizen's 8651 Manual PDFDocument16 pagesCitizen's 8651 Manual PDFtfriebusNo ratings yet

- Depression List of Pleasant ActivitiesDocument3 pagesDepression List of Pleasant ActivitiesShivani SinghNo ratings yet

- Course Syllabus Manufacturing Processes (1) Metal CuttingDocument4 pagesCourse Syllabus Manufacturing Processes (1) Metal CuttingG. Dancer GhNo ratings yet

- Keygene Strengthens Its Patent Portfolio On Keypoint Mutation BreedingDocument1 pageKeygene Strengthens Its Patent Portfolio On Keypoint Mutation Breedingapi-99034713No ratings yet

- Wago PCB Terminal Blocks and Connectors Catalog 7Document105 pagesWago PCB Terminal Blocks and Connectors Catalog 7alinupNo ratings yet

- Presentation of DR Rai On Sahasrara Day Medical SessionDocument31 pagesPresentation of DR Rai On Sahasrara Day Medical SessionRahul TikkuNo ratings yet

- Biology 2 Chapter 4Document61 pagesBiology 2 Chapter 4Malas Nak TaipNo ratings yet

- Generic 5S ChecklistDocument2 pagesGeneric 5S Checklistswamireddy100% (1)

- Faculty Based Bank Written PDFDocument85 pagesFaculty Based Bank Written PDFTamim HossainNo ratings yet

- Post Traumatic Stress DisorderDocument2 pagesPost Traumatic Stress Disorderapi-188978784100% (1)

- Narrative ReporDocument3 pagesNarrative ReporMARK LUKE ULITNo ratings yet

- 13 Lombe Mumba Ramson 2017 Knowledge Attitude and Practice of Breast Self Examination For Early Detectoin of Breast Cancer Among Women in Roan Constituency in Luanshya Copperbelt Province ZambiaDocument9 pages13 Lombe Mumba Ramson 2017 Knowledge Attitude and Practice of Breast Self Examination For Early Detectoin of Breast Cancer Among Women in Roan Constituency in Luanshya Copperbelt Province ZambiaArick Frendi AndriyanNo ratings yet

- Existensive Happiness by AristotleDocument2 pagesExistensive Happiness by AristotleIan Robert Roa NovalNo ratings yet

- RISK MANAGEMENT - Imo Multilingual Glossary On Risk Management (Secretariat)Document17 pagesRISK MANAGEMENT - Imo Multilingual Glossary On Risk Management (Secretariat)Martin NiNo ratings yet

- Fin e 59 2016Document10 pagesFin e 59 2016Brooks OrtizNo ratings yet

- Posi LokDocument24 pagesPosi LokMarcel Baque100% (1)

- Rar Vol11 Nro3Document21 pagesRar Vol11 Nro3Valentine WijayaNo ratings yet

- This Unit Group Contains The Following Occupations Included On The 2012 Skilled Occupation List (SOL)Document4 pagesThis Unit Group Contains The Following Occupations Included On The 2012 Skilled Occupation List (SOL)Abdul Rahim QhurramNo ratings yet

- G.f.roof Beam & Slab DetailDocument1 pageG.f.roof Beam & Slab Detailahmad anasNo ratings yet

- Gloria Pfoltzer Theresa Morris, an Infant, by Mother and Next Friend Christopher Morris, an Infant, by Mother and Next Friend Randy Morris, an Infant, by Mother and Next Friend v. Fairfax County Department of Human Development Susan Manzo Paulette Byrd Florence Hannigan, and Louis Villafane, 966 F.2d 1443, 4th Cir. (1992)Document10 pagesGloria Pfoltzer Theresa Morris, an Infant, by Mother and Next Friend Christopher Morris, an Infant, by Mother and Next Friend Randy Morris, an Infant, by Mother and Next Friend v. Fairfax County Department of Human Development Susan Manzo Paulette Byrd Florence Hannigan, and Louis Villafane, 966 F.2d 1443, 4th Cir. (1992)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Current and Voltage Controls 3-Phase AC Max. Current Control Type S 178Document3 pagesCurrent and Voltage Controls 3-Phase AC Max. Current Control Type S 178Felipe FarfanNo ratings yet

- FINALE Final Chapter1 PhoebeKatesMDelicanaPR-IIeditedphoebe 1Document67 pagesFINALE Final Chapter1 PhoebeKatesMDelicanaPR-IIeditedphoebe 1Jane ParkNo ratings yet

- Cape 2 Biology - Homeostasis &excretionDocument9 pagesCape 2 Biology - Homeostasis &excretionTamicka BonnickNo ratings yet

- Factory OverheadDocument2 pagesFactory OverheadKeanna Denise GonzalesNo ratings yet