Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Will Eisner

Uploaded by

miltodiavoloCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Will Eisner

Uploaded by

miltodiavoloCopyright:

Available Formats

I

n high school I avidly enrolled in the first Film Literacy

course offered within the curriculum of the San Francisco

Unified School District. For my term final, I offered the class

a presentation on the corollary between cinema and comic-

books, utilizing one of those old-fashioned overhead projectors

and an array of pages from a unique 1940s comic-strip/comic-book

hybrid called The Spirit. Soon after, an updated version of The Spirit,

guest-starring (in highly unflattering portrayals) members of my

schools faculty, written and illustrated by yours truly, appeared in

the Yearbookexpediting my exit, triumphantly, from 12 years of

academic captivity. I was one precocious teenaged smartass.

53 NOIR CITY I SPRING 2015 I filmnoirfoundation.org

M

y love of film noir directly corre-

sponded with my discovery of, and

devotion to, The Spirit. I had always

been a comics-loving kid, and my

childhood was filled with blissful escapes into

pitco-fiction of all types: Marvel, DC, Archie,

Classics Illustrated (later, my beloved ECs), as

well as venerable newspaper strips such as Steve

Canyon, Dick Tracy, Rip Kirby, and more.

Amazingly, it wasnt until I read Jim Sterankos

mind-expanding History of Comics, Vol. 2 that

I learned about the greatest and most influen-

tial comics artist of all-time, Will Eisner, and his

deathless hero, The Spirit.

What still amazes me about The Spirit is that

its creation, development, peak, and demise all

corresponded to the same arc as the original Portrait of the young man as an artist: Eisner is the 1940s

Will Eisner was

a genuine artist

more so in my

opinion than,

say, a legendary

director such as

Fritz Lang

American film noir era. It was not an homage

to noir. Eisner was creating his own version of

it, simultaneous with the release of The Killers

(1946), Crossfire (1947), T-Men (1947) and all

the rest. Few comics were as spot-on in nailing

the noir zeitgeist. Eisner wasnt emulating or

satirizing, he was doing the same thing, at the

same time, in a different medium. He was part

of the movement, not a commentator on it.

Late 1940s comics such as Crime Does

Not Paywhich should have been the funny

book equivalent of film noirwere, oddly

enough, some of the most graphically pedes-

trian titles on the stands. Despite the lurid

covers, the interior art was usually rushed and

amateurish; these were the pulp-paper dop-

pelgangers of Poverty Rows no-budget Bs,

filled with flat lighting, flatter dialogue, and

unimaginative visuals.

By contrast, Will Eisner was a genuine art-

istmore so in my opinion than, say, a legend-

ary director such as Fritz Lang. While Lang

searched for projects that fit his particular

skills, and often took megalomaniacal advan-

The author in his studio today, displaying pages he created in high school as a tribute to Will Eisner's The Spirit tage of others hard work, Eisner anchored

54 NOIR CITY I SPRING 2015 I filmnoirfoundation.org

longer an illustrator, he was a cartoonist.2

His drawings evoked the gamut of action

and emotion, from slapstick comedy to

heart-rending tragedy. If Expression-

ism is a photographic technique used

to make exterior environments reflect

the inner lives of characters, exaggera-

tion is the cartoonists essential tool, and

few sequential artists (the term Eisner

eventually settled on) used it better than

Eisner. He also crafted the most soni-

cally conceived comics everweaving in

graphically rendered music, songs, and

sardonic snippets of advertising from

the radio. It was a fully formed milieu in

which rubber-boned, baggy-pants char-

acters ricocheted through a dank and

dreadful city of endless shadows and

sudden death. Reading The Spirit was at

times like watching Red Skelton, Oscar

Levant, and the Three Stooges careen

through a film directed by Robert Siod-

makwith Cary Grant (see: Arsenic and

Old Lace) as the dumbfounded, dou-

ble-taking Denny Colt. And nobody

nobodycreated better femmes fatales,

Femme fatale Skinny Bones seemed a Sunday funnies version of vixenish Veronica Lake ...

all of them bewitching blends of Ava

his ass at the drawing board, every single day, to create entire films Gardner and Linda Darnell, Lauren Bacall and Veronica Lake: PGell,

noireight-page masterworks spilling over with comedy, pathos, Sand Saref, Dulcet Tone, Flaxen Weaver, Silk Satin, Autumn Mews,

action, intrigue, love and painusing nothing more than India ink Thorne Strand, Wild Rice (a masochistic rich girl!), Powder Pouf, and

on white Bristol board. even Olga Bustle (The Girl with the Big, Big Eyes), a parody of Jane

Starting in 1940, at only 23 years of age, Eisners studio began Russell in The Outlaw.

producing a 16-page digest-sized supplement for syndication

to 20 American Sunday newspapers. It was a way of placing a

comic book within the cherished Sunday Funnies. In addi-

tion to the seven-page feature that led off The Spirit Section,

Eisner also wrote and edited the two four-page backup features,

Mr. Mystic and Lady Luck.

When I created The Spirit, Eisner once said, I never had

any intention of creating a superhero. I never felt The Spirit

would dominate the feature. He served as a sort of an identity

for the strip. The stories were what I was interested in. The silly

domino mask worn by Denny Colt (The Spirits real identity) was

Eisners sole concession to the Syndicate that gave him the con-

tracttheyd specifically requested a superhero. But Eisner was

more interested in drawing tales from life in his lower-middle-

class New York Jewish neighborhood, which he rendered as a

noir milieu more vivid than Naked City or Cry of the City: crum-

bling tenements, rain-slick streets, smoke-filled crime dens. Skip

McCoys wharfside shack in Pickup on South Street is straight

out of Eisners New York. The Spirits cast of characters, from

vicious hoodlums to impossibly shapely femme fatalesand

an endless array of sympathetic but doomed loserswas more

colorful than the cast of any Hollywood crime meller.

It was after Eisner returned from WWII service1 that The Spirit,

like the film noir movement, really hit its stride. Eisner was no ... and it was easy (for me at least) to imagine Cary Grant as the undead Denny Colt

2 In the interest of accuracy, it must be noted that Eisner, even postwar, had able

1 During those three years, Eisner employees such as Bob Powell and Lou Fine assistants aiding in the creation of The Spirit: John Spanger, Klaus Nordling, Jerry

handled most of the illustrating chores. Grandenetti, Andre LeBlanc, Manny Stallman, Jules Feiffer, and Wallace Wood.

filmnoirfoundation.org I SPRING 2015 I NOIR CITY 55

Selected panels from some of my favorite Spirit stories: Ten Minutes (left); Fox at Bay (center, right)

One of Eisner's strongest (and graphically bizarre) stories, The Killer, put the reader inside the head of a traumatized WWII vet.

The fate of Gerhard Shnobble (left) might have traumatized young readers, but the recurring appearances of the notorious PGell (right) no doubt perked them back up

56 NOIR CITY I SPRING 2015 I filmnoirfoundation.org

Eisner continues to exert his influence: the 2014 NOIR CITY poster was an homage to the splash page of The Spirit Section from October 6, 1946

Eisners specific genius was crossing those deep Germanic shad- The Story of Gerhard Shnobble (September 5, 1948)Eisner

ows with a particular type of Jewish morality playembodying in the fantasist spins the tale of a small, anonymous man who one day

a single artist the cultural DNA that spawned the entire film noir defiantly decides to reveal to the world his special powerhe can fly.

movement. Heres a cross-section of Spirit And he does, in a breathtakingly rendered

stories that shows the full range of Eisners sequence only to be hit in the crossfire of

approach and ambition:

Ten Minutes (September 11, 1949)a

(In its time) no a shootout and left to die as anonymously

as hed lived. Rememberthese were

perfectly executed short story (in which The

Spirit barely appears) that explores the crucial

one granted his comics! For kids!

Sand Saref and Bring in Sand Saref

decision in a mans life to cross the line and

becomes a criminal. Fate exacts immediate

kind of genius the (January 8 & 15, 1950)a two-part thriller

that Eisner originally created to introduce

comeuppance. Eisner makes the petty robbery

of a candy store feel like a mythic analogy for

appreciation it a new non-masked character, John Law.

Reworked as a Spirit story, its a Sunday fun-

every bad decision ever made.

Fox at Bay (October 23, 1949)a

deserved; his nies version of Cry of the City with the added

punch of Denny Colt (cop) and Sand Saref

doctor takes his study of aberrant behavior

and its effects on the human nervous sys-

masterpieces were (crook) sharing an unrequited (and sexy!)

love going back to childhood. In 14 pages,

tem to the extremekeeping scrupulous

notes on the murders he commits solely for

tossed out with the Eisner crafted his own pitch-perfect film noir.

Of course, when Eisner was in his creative

scientific research. No noir film of the era

offered a villain this daring.

trash every week. prime he was largely unappreciated. Funny

books were for kids; no one granted his kind

The Killer aka Henry the Veteran of genius the appreciation it deserved; his mas-

(December 8, 1946)told its tale of a mur- terpieces were tossed out with the trash every

derously vengeful GI in the first-personin some panels literally week. But Eisner wasnt only an artistic geniushe was a savvy business-

through the eyes (eye-sockets!) of the title charactermore than a man. His deal to produce The Spirit Section specified that he retain all

year before Robert Montgomery pulled his subjective camera stunt rights to the workthe character, the stories, the art. And when the kids

with The Lady in the Lake (1947). who loved The Spirit had grown to adulthood (see sidebar), Eisner finally

filmnoirfoundation.org I SPRING 2015 I NOIR CITY 57

got his dueunlike other noir titans like John Alton and Jim Thompson, combining several thematically linked short tales into a single volume.

who died bitter, never knowing their work would one day receive world- He went on to produce a series of graphic collections detailing the

wide recognition. Not only was Eisner eventually reveredhe was paid. history of New Yorks immigrant Jewish communities, including The

Every time one of his stories was reprintedhe got paid again. Such is Building, A Life Force, Dropsie Avenue and To the Heart of the Storm.

his reputation, the comic-book industry equivalent of the Oscar bears Not to discount this later work, but Eisners legacy will always

his name: The Eisner Award. be The Spirit, a masterpiece that was an essential part of an era that

Even more significantly, Eisner continued to create into his eighties, featured the best work of many talents forever inked with noir: Wee-

producing an astounding body of work and amassing a legacy second gee, Raymond Chandler, Orson Welles, John Alton, Robert Siodmak,

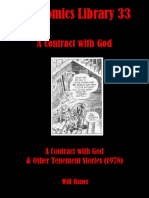

to none. A Contract with God, and Other Tenement Stories (Bar- Humphrey Bogart.

onet Books, October 1978) was an early example of the graphic novel, In my book, Will Eisner is as great as any of them.

WARREN PUBLISHINGS SPIRIT REPRINTS

Will Eisners newspaper supplement The Spirit ended in 1952. But in 1974, Eisner had

two potential suitors call him about resurrecting The Spirit: Marvel Comics publisher

Stan Lee and Warren Magazine publisher Jim Warren. Lee wanted to restart The Spirit

and have the character be part of the Marvel Universe, while Warren wanted to reprint

the original Spirit sections that he read as a youth in Philadelphia. Eisner had no desire

to lose creative control and see his character fall into the hands of a large comic book

publisher. So, in April 1974, Jim Warren began reprinting The Spirit as a black and white

(with an eight-page color section) bi-monthly magazine.

Comic-book readers coming of age in the 1970s discovered Eisners work through

Warrens reprints. Fans of Warrens Creepy and Eerie saw The Spirits beautifully drawn,

vibrantly colored covers on newsstand shelves and were compelled to buy it. The stories

were more complex and interesting than most of the comics being published at that time.

And one of the most memorable features of Warrens Spirit was the full-color section in

each issue, several of which were colored by comic-book legend Richard Corben.

The magazines first letters column contained missives from a veritable Whos Who

of comic-book artists: Alex Toth, Wally Wood, and Neal Adams all lauded the return of

Eisners masterpiece. Adams wrote: Finally, Will Eisner is back on the scene to teach

us how to draw and tell a comic-book story. For those new to comics, his approach is

Eisner's splash pages were often the epitome of noir style

fresh and original. For those who have forgotten, his unique style is a gentle reminder of

the way comics should be. Frank Miller

also discovered Eisner through the

Warren reprints. As a 13-year-old, he

thought the stories were new, because

they were so far ahead of anything else

being published.

The Warren reprints lasted only 16

issues, but they revived Eisners legacy

for a new generation.

Michael Kronenberg

Eisner's original art (left)

and Richard Corben's

painted colors (right) for the

finished cover of Warren's

The Spirit #3

58 NOIR CITY I SPRING 2015 I filmnoirfoundation.org

You might also like

- Silver AgeDocument18 pagesSilver AgeMaria Carolina Reis67% (3)

- The Spirit Magazine Will Eisner PDFDocument66 pagesThe Spirit Magazine Will Eisner PDFewwillatgmaildotcomNo ratings yet

- Will Eisner, A Spirited LifeDocument53 pagesWill Eisner, A Spirited Lifealbert.dw3l692No ratings yet

- Case Against Stan LeeDocument303 pagesCase Against Stan LeeΡοντριγκο Φιγκουειροα67% (3)

- Jackkirby PDFDocument34 pagesJackkirby PDFphotoimation100% (2)

- Kirby Collector 22 PreviewDocument18 pagesKirby Collector 22 PreviewBruno Azevedo100% (1)

- Watchmen The Judge of All The EarthDocument48 pagesWatchmen The Judge of All The EarthUVCW6No ratings yet

- KirbyCollector54Online PDFDocument85 pagesKirbyCollector54Online PDFdenby_m100% (2)

- Modern Masters Volume 7 - Jhon ByrneDocument27 pagesModern Masters Volume 7 - Jhon ByrneJulianMessina100% (2)

- Comic Moebius PDFDocument2 pagesComic Moebius PDFChris100% (1)

- The Comics of R. Crumb: Underground in the Art MuseumFrom EverandThe Comics of R. Crumb: Underground in the Art MuseumRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Kirby Collector 35 PreviewDocument22 pagesKirby Collector 35 PreviewMuhammad Haider100% (1)

- The Great Comic Book ArtistsDocument148 pagesThe Great Comic Book Artistssilezukuk93% (14)

- Alex Toth - Crushed Gardenia - 1953Document4 pagesAlex Toth - Crushed Gardenia - 1953NickSFNo ratings yet

- Milton Caniff Article PDFDocument8 pagesMilton Caniff Article PDFSteve BillingsNo ratings yet

- The Rocketeer/The Spirit: Pulp Friction! #1 (Of 4) PreviewDocument12 pagesThe Rocketeer/The Spirit: Pulp Friction! #1 (Of 4) PreviewGraphic Policy100% (1)

- Rocketeer / The Spirit: Pulp Friction PreviewDocument12 pagesRocketeer / The Spirit: Pulp Friction PreviewGraphic PolicyNo ratings yet

- My Captain America: A Granddaughter's Memoir of a Legendary Comic Book ArtistFrom EverandMy Captain America: A Granddaughter's Memoir of a Legendary Comic Book ArtistNo ratings yet

- Art of Howard Chaykin Hardcover PreviewDocument13 pagesArt of Howard Chaykin Hardcover PreviewGraphic PolicyNo ratings yet

- (Will Eisner) Contract With God PDFDocument194 pages(Will Eisner) Contract With God PDFMilton Medellín100% (5)

- Airboy Archives, Vol. 1 PreviewDocument15 pagesAirboy Archives, Vol. 1 PreviewGraphic Policy100% (1)

- The Great Comic Book Artists PDFDocument148 pagesThe Great Comic Book Artists PDFJoaquim Fernandes100% (4)

- The Art of Harvey Kurtzman: The Mad Genius of ComicsFrom EverandThe Art of Harvey Kurtzman: The Mad Genius of ComicsRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (10)

- Will Eisner - Heart of The StormDocument211 pagesWill Eisner - Heart of The StormIsaacSilver100% (10)

- Modern Masters Volume 8 - Walter SimonsonDocument27 pagesModern Masters Volume 8 - Walter SimonsonJulianMessina100% (1)

- Art DrawingsDocument24 pagesArt Drawingsjjosue583% (6)

- The New England Life of Cartoonist Bob Montana: Beyond the Archie Comic StripFrom EverandThe New England Life of Cartoonist Bob Montana: Beyond the Archie Comic StripRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Bulletman Comics (Fawcett Comics) Issue #7Document68 pagesBulletman Comics (Fawcett Comics) Issue #7K100% (1)

- Comicbook Creator 2 BonusDocument20 pagesComicbook Creator 2 Bonusdenby_m100% (3)

- The Dark Knight ReturnsDocument201 pagesThe Dark Knight Returnsmax100% (1)

- Comic Book CreatorDocument15 pagesComic Book CreatorAristarco Jj100% (3)

- My Greatest Ambition PDFDocument7 pagesMy Greatest Ambition PDFSonia PurinNo ratings yet

- John Romita Jazz PreviewDocument44 pagesJohn Romita Jazz Previewcos73100% (3)

- RT Lamour: Edited by Jim Amash and Eric Nolen-WeathingtonDocument38 pagesRT Lamour: Edited by Jim Amash and Eric Nolen-WeathingtonSérgio GodinhoNo ratings yet

- More Wally Wood ImagesDocument5 pagesMore Wally Wood Imageshorratio100% (1)

- Alan Moore - Comics As Performance - Fiction As Scalpel - Annalissa Di Liddo - 160473213xDocument212 pagesAlan Moore - Comics As Performance - Fiction As Scalpel - Annalissa Di Liddo - 160473213ximageorge130% (1)

- Stripped Convention GuestsDocument13 pagesStripped Convention GuestsGraphic Policy100% (1)

- Frazetta's Funny Stuff PreviewDocument10 pagesFrazetta's Funny Stuff PreviewGraphic PolicyNo ratings yet

- Steve Canyon, Vol. 4: 1953-1954 PreviewDocument25 pagesSteve Canyon, Vol. 4: 1953-1954 PreviewGraphic PolicyNo ratings yet

- A Complete History of American Comic Books Afterword by Steve GeppiDocument2 pagesA Complete History of American Comic Books Afterword by Steve Geppinita0% (3)

- The Art of Todd McFarlaneDocument8 pagesThe Art of Todd McFarlaneUSA TODAY Comics33% (3)

- Let's Do Nothing by Tony Fucile - Q&A With AuthorDocument2 pagesLet's Do Nothing by Tony Fucile - Q&A With AuthorCandlewick Press100% (1)

- Stan Lee's How To Write Comics - ExcerptDocument14 pagesStan Lee's How To Write Comics - ExcerptCrown Publishing Group52% (21)

- Alan Moore Big Numbers Interview PDFDocument15 pagesAlan Moore Big Numbers Interview PDFRos SparkesNo ratings yet

- John Byrne Babes SketchBookDocument31 pagesJohn Byrne Babes SketchBookdbw1075% (20)

- The Story of BatmanDocument44 pagesThe Story of BatmanRty DddNo ratings yet

- Comics - Eisner, Will - A Contract With God - 1978 - The Comics Library 33 - ENG - p195 PDFDocument195 pagesComics - Eisner, Will - A Contract With God - 1978 - The Comics Library 33 - ENG - p195 PDFentrambasaguas100% (2)

- Comics 101 - How-To & History Lessons From The Pros! (FCBD) Two Morrows) (2007)Document36 pagesComics 101 - How-To & History Lessons From The Pros! (FCBD) Two Morrows) (2007)Jevgenijs Cernihovics95% (20)

- Alterego 94 OnlineDocument94 pagesAlterego 94 OnlineCarlos DamascenoNo ratings yet

- I Killed Adolf HitlerDocument50 pagesI Killed Adolf Hitlerriversoto185% (20)

- Taking Off The Mask: Invocation and Formal Presentation of The Superhero Comic in Moore and Gibbons' WatchmenDocument122 pagesTaking Off The Mask: Invocation and Formal Presentation of The Superhero Comic in Moore and Gibbons' WatchmenSamuel Effron100% (2)

- Artkub PreviewDocument20 pagesArtkub PreviewMike Castilho100% (1)

- Memento MoriDocument12 pagesMemento MorimiltodiavoloNo ratings yet

- Mun ForteDocument30 pagesMun FortemiltodiavoloNo ratings yet

- Wenger PDFDocument32 pagesWenger PDFmiltodiavoloNo ratings yet

- Mutus Liber - The Mute Book of AlchemyDocument2 pagesMutus Liber - The Mute Book of Alchemymiltodiavolo0% (2)

- Cluff MA F2014Document67 pagesCluff MA F2014miltodiavoloNo ratings yet

- The Alchemist (Musician)Document9 pagesThe Alchemist (Musician)miltodiavoloNo ratings yet

- Photographing The DeadDocument1 pagePhotographing The DeadmiltodiavoloNo ratings yet

- Dictionary of The Forgotten OnesDocument17 pagesDictionary of The Forgotten Onesxdarby100% (1)

- 6241Document17 pages6241miltodiavoloNo ratings yet

- Bando Perfezionamento IngDocument10 pagesBando Perfezionamento IngmiltodiavoloNo ratings yet

- I HaveDocument1 pageI HavemiltodiavoloNo ratings yet

- Memento MoriDocument12 pagesMemento MorimiltodiavoloNo ratings yet

- Lovecraft FilmsDocument5 pagesLovecraft FilmsmiltodiavoloNo ratings yet

- AlchemyDocument18 pagesAlchemymiltodiavoloNo ratings yet

- Cmyc To RGB and RGB To CmycDocument12 pagesCmyc To RGB and RGB To CmycmiltodiavoloNo ratings yet

- Photoshop Shortcuts A4Document20 pagesPhotoshop Shortcuts A4miltodiavoloNo ratings yet

- Standards and ProtocolsDocument44 pagesStandards and ProtocolsmiltodiavoloNo ratings yet

- Scrivener ShortcutsDocument4 pagesScrivener ShortcutsmiltodiavoloNo ratings yet

- Ghosts Spirits & Hauntings TypesDocument7 pagesGhosts Spirits & Hauntings TypesmiltodiavoloNo ratings yet

- Paranormal DictionaryDocument9 pagesParanormal DictionarymiltodiavoloNo ratings yet

- Ghost HuntingDocument4 pagesGhost HuntingmiltodiavoloNo ratings yet

- PoltergeistDocument3 pagesPoltergeistmiltodiavoloNo ratings yet

- Apparitional ExperienceDocument4 pagesApparitional ExperiencemiltodiavoloNo ratings yet

- Haunted HouseDocument4 pagesHaunted HousemiltodiavoloNo ratings yet

- Astral ProjectionDocument5 pagesAstral ProjectionmiltodiavoloNo ratings yet

- 10 Jms 009 Asrarul Grossly CasesDocument2 pages10 Jms 009 Asrarul Grossly CasesmiltodiavoloNo ratings yet

- GhostsDocument8 pagesGhostsmiltodiavoloNo ratings yet

- Books To BuyDocument2 pagesBooks To BuymiltodiavoloNo ratings yet

- Best Horror BooksDocument2 pagesBest Horror BooksmiltodiavoloNo ratings yet

- Test 32Document3 pagesTest 32Cao Mai-PhuongNo ratings yet

- Weber Marine Floor ORIGINALDocument9 pagesWeber Marine Floor ORIGINALDiko Satria PutroNo ratings yet

- ) Caterina de Nicola Selected Works (Document19 pages) Caterina de Nicola Selected Works (Catecola DenirinaNo ratings yet

- TOPAZ GLOSS EMULSIONDocument2 pagesTOPAZ GLOSS EMULSIONsyammcNo ratings yet

- Parappa The Rapper 2Document65 pagesParappa The Rapper 2ChristopherPeter325No ratings yet

- How To Use The Browse Tree Guide: Background InformationDocument135 pagesHow To Use The Browse Tree Guide: Background InformationSamir ChadidNo ratings yet

- Famous Landmark PresentationDocument46 pagesFamous Landmark PresentationLuceNo ratings yet

- Tulip Dress Pattern Multipage PDFDocument21 pagesTulip Dress Pattern Multipage PDFEvelina AnileveNo ratings yet

- Robert Welsh: Cow ofDocument35 pagesRobert Welsh: Cow ofSCRIBDUSNo ratings yet

- R. J. Crum, Roberto Martelli, The Council of Florenece and Medici Palace ChapelDocument16 pagesR. J. Crum, Roberto Martelli, The Council of Florenece and Medici Palace Chapelgenoveva011No ratings yet

- Procreative: Ancient Egyptian Mythology Ra Egyptian Goddesses Hathor Sekhmet Bastet Wadjet MutDocument2 pagesProcreative: Ancient Egyptian Mythology Ra Egyptian Goddesses Hathor Sekhmet Bastet Wadjet MutRegie Rey AgustinNo ratings yet

- Ingles 3T Nivel Bajo TDocument4 pagesIngles 3T Nivel Bajo TciclobasicohuergoNo ratings yet

- The Historical Development of TrademarksDocument3 pagesThe Historical Development of Trademarksmarikit.marit100% (1)

- Avd ListDocument7 pagesAvd ListRasheed Basha ShaikNo ratings yet

- m006 Modal Test Junio 17Document2 pagesm006 Modal Test Junio 17Alex Saca MoraNo ratings yet

- TutankhamunDocument14 pagesTutankhamunJoan AdvinculaNo ratings yet

- Brett Garsed Profile: Australian Guitarist's Dreamy Solo Debut "Big SkyDocument25 pagesBrett Garsed Profile: Australian Guitarist's Dreamy Solo Debut "Big SkyHernánCordobaNo ratings yet

- John Keats Poetry - II 1st Assignment-1Document4 pagesJohn Keats Poetry - II 1st Assignment-1Muhammad AbidNo ratings yet

- Film Analysis Glas by Bert Haanstra: Hrithik Ameet Surana 1810110081Document3 pagesFilm Analysis Glas by Bert Haanstra: Hrithik Ameet Surana 1810110081hrithikNo ratings yet

- Best Tamil Books Collection for Children and AdultsDocument2 pagesBest Tamil Books Collection for Children and Adultsyokesh mNo ratings yet

- Comparison Between Buddhism and Sophian Christian TraditionDocument13 pagesComparison Between Buddhism and Sophian Christian TraditionAbobo MendozaNo ratings yet

- Wasteland Fury - Post-Apocalyptic Martial Arts - Printer FriendlyDocument29 pagesWasteland Fury - Post-Apocalyptic Martial Arts - Printer FriendlyJoan FortunaNo ratings yet

- Answer To AppraisalDocument75 pagesAnswer To Appraisallwalper100% (2)

- Online Vegetable StoreDocument10 pagesOnline Vegetable Storestudent id100% (1)

- Architectural Design of Public BuildingsDocument50 pagesArchitectural Design of Public BuildingsAr SoniNo ratings yet

- Celloidin EmbeddingDocument14 pagesCelloidin EmbeddingS.Anu Priyadharshini100% (1)

- Emcee Script For Turn Over CeremonyDocument1 pageEmcee Script For Turn Over CeremonyJackylou Saludes91% (77)

- 426 C1 MCQ'sDocument5 pages426 C1 MCQ'sKholoud KholoudNo ratings yet

- You Dian TianDocument5 pagesYou Dian TianWinda AuliaNo ratings yet

- Elante Mall Chandigarh: Efforts By: Harshita Singh Amity School of Architecture & PlanningDocument11 pagesElante Mall Chandigarh: Efforts By: Harshita Singh Amity School of Architecture & PlanningShaima NomanNo ratings yet