Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Tetley

Uploaded by

Force MapuCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Tetley

Uploaded by

Force MapuCopyright:

Available Formats

Qualitative Health Research

Volume 19 Number 9

September 2009 1273-1283

Using Narratives to Understand 2009 The Author(s)

10.1177/1049732309344175

Older Peoples Decision-Making Processes

http://qhr.sagepub.com

Josephine Tetley

Open University, Milton Keynes, United Kingdom

Gordon Grant

Sheffield Hallam University, Sheffield, United Kingdom

Susan Davies

University of Sheffield, Sheffield, United Kingdom

Despite the availability of health and social care services designed to support people in their own homes, older

people often underuse or refuse these services. It is now acknowledged that this phenomenon contributes to older

people being admitted to hospital and long-term care in circumstances that could be avoided. To understand how the

uptake of supportive and preventative services can be improved, the first author, supervised by the second and third

authors, developed a constructivist inquiry to explore what factors enhance or bar service use. This article describes

how narratives were used not only to help identify decision- and choice-making influences, but also as a way of

enhancing the hermeneutic processes associated with constructivism.

Keywords: constructivism; health care, decision making; hermeneutics; narrative methods; older people; social

services, utilization

O lder people often underuse or refuse to use health

and social care services designed to support them

in their own homes (Joseph Rowntree Foundation,

resources, and the cultural sensitivity of mainstream

services might affect older peoples decision- and

choice-making processes (Atkin, 1998; Kane & Kane,

2004). This has contributed to increased pressure on 2001; Tanner, 2001; Wenger, 1999).

acute hospital services, because older people are There has also been increased demand for user

being admitted to hospital or long-term institutional involvement in research and practice development

care, which might otherwise have been avoided (Nolan, Hanson, Grant, & Keady, 2007). However,

(Health and Social Care Change Agent Team, 2004). some groups in society do not have the same oppor-

Consequently, current United Kingdom government tunities to influence service development because

policy continues to focus on developing services to meaningful participation is affected by a range of

support older people in the community and on reduc- issues, including cultural divisions, language barri-

ing the numbers of older people in hospital and long- ers, gender, ill health, time, and resources (Boote,

term care (Department of Health, 2006a, 2006b). Telford, & Cooper, 2002; Fudge, Wolfe, & McKevitt,

Despite this investment and commitment to improv- 2007). In this article we describe how narratives

ing care and services, previous studies of the uptake were used with older peopleoften excluded from

of health and social care services indicated that more mainstream consultation processesto engage them

research was required to understand how local author- in research and to evaluate the hermeneutic pro-

ity budget constraints, reduction in number of hos- cesses associated with constructivism.

pital beds, mental capacity issues, individual financial For researchers seeking to gain insights into

peoples experiences of a particular issue, a con-

structivist methodology is particularly useful, as this

Authors Note: We thank NHSE Trent, who provided funding

approach acknowledges that peoples understand-

for this study. We also thank Elizabeth Hanson, Research Leader,

Swedish Family Care Competence Centre, and Liz Clark, Deputy ings of their lives and situations are multiple and

Director of the OU-RCN Alliance, for their constructive com- complex (Guba & Lincoln, 1989). To appreciate how

ments on earlier versions of this article. personal understandings and life experiences shape

1273

Downloaded from qhr.sagepub.com at NORTH CAROLINA STATE UNIV on April 7, 2015

1274 Qualitative Health Research

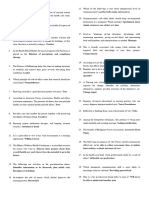

Figure 1

Hermeneutic Circle

Literature

Interviews

Narrative

Constructions

Inquirer Coparticipant

Cultural heritage Cultural heritage

Personal/Professional Personal/Professional

experience Constructions experience

Formal/informal Formal/informal

Tested

knowledge knowledge

More Informed

Personal knowing Personal knowing

Participant

Observation

individuals actions, constructivism requires investiga- Although Rodwell considers the hermeneutic circle

tors to find ways of working that enable them to work within a constructivist inquiry, her approach does not

in partnership and negotiate meanings and interpreta- take account of Guba and Lincolns argument that the

tions with relevant stakeholders (Appleton & King, constructions generated are always shaped by human

1997; Geanellos, 1998; Koch, 1996; Rodwell, 1998; experiences (Guba & Lincoln, 1989).

Schwandt, 2000). By working in this way, it is argued While looking for a way of accounting for human

that changes to health and social care practice arising experiences within the hermeneutic processes of the

from these insights will be more meaningful to ser- study, the first author encountered the work of

vice users (Mitchell & Koch, 1997; Rodwell, 1998). Engebretson and Littleton (2001). This work was of

Methodologically, constructivism is underpinned particular interest as it presented a constructivist-based

by approaches that aim to collect data in a dialectic model for nursing practice which recognized that a

(reflective) and hermeneutic (jointly constructed) nurse should take account of the culture (beliefs and

manner (Guba & Lincoln, 1989, King & Appleton, values), experience (both personal and professional),

1999; Laughlin & Broadbent, 1996; Wainwright, knowledge (formal and informal), and personal know-

1997). If researchers are to share information and ing (tacit knowledge) of both parties to understand a

undertake joint working within a constructivist inquiry, clients health care needs. Engebretson and Littletons

the use of a hermeneutic circle is recommended, as (2001) model was therefore modified and used to create

this process enables the inquirer to introduce claims, a hermeneutic circle for this study. This model was of

concerns, and issues from other respondents; their particular value, as it enabled us to illustrate how peo-

own experiences; and the literature into a process for ples stories of decision making could be informed not

testing and verification (Engbretson & Littleton, only by data gathered during the course of the study, but

2001; Guba, & Lincoln, 1989; Lincoln & Guba, 1985; also by professional experiences and knowledge of the

Rodwell, 1998). However, Rodwell (1998) argues literature relevant to the study (see Figure 1).

that this does not have to be a physical circle, where The modified model provided a theoretical frame-

the inquirer and respondents are in constant interac- work within which the data and personal experiences

tion. Instead, it is suggested that the hermeneutic cir- could be brought together. However, it was recog-

cle should be a forum where perspectives can be nized that a practical vehicle was needed through

presented, considered, evaluated, understood, rejected, which older people could be engaged in hermeneutic

or incorporated into an emerging understanding of the processes. Narratives were identified as a way in

phenomena under investigation (Rodwell, 1998). which this could be achieved.

Downloaded from qhr.sagepub.com at NORTH CAROLINA STATE UNIV on April 7, 2015

Tetley et al. / Narratives and Decision-Making Processes 1275

Method factors identified earlier in this article as barriers to

consultation and service development.

The use of narratives to understand the individual Ethics approval for the study was granted by a

experience of health and social care has a long history local National Health Service research ethics com-

(see, for example, Bytheway, 2003; Hogarth & Marks, mittee. As part of the approval process, information

1998; Johnson, 2004). However, more recently there sheets and consent forms were developed for the

has been a renewed interest that has recognized the participant observation and interview phases of the

value of narratives to health and social care practitio- study. At each study site the first author spent time

ners (Bornat, 1999; Brown, 2008; Bytheway, 2003; talking to people, explaining the nature of the study

Greenhalgh & Hurwitz, 1998; Housley, 2000; Johnson, and why she was engaging people in different ser-

2004; Nygren, Norberg, & Lundman, 2007; Ridge & vice settings. After several visits, people were then

Ziebland, 2006). Although Ellis and Bochner (2000) asked if they would sign consent forms to give per-

argue that narratives can enable people to see and mission for notes to be made by the first author

understand their own story, Greenhalgh and Hurwitz based on her observations of them and/or conversa-

(1998, p. 381) claim that narratives can help practitio- tions with them. Some of the challenges associated

ners and researchers understand peoples experiences with this process are documented in a separate article

more holistically, because they provide a meaning, (Tetley, et al. 2003).

context and perspective for the patients predica- The number of people attending each of the ser-

ment. Furthermore, Greenhalgh and Hurwitz (1998) vices varied. At the African Caribbean center, approx-

suggest that narratives serve an important purpose in imately 40 people attended the luncheon club, 10

education and research because they are memorable, women attended the craft group, and home support

grounded in experience, encourage reflection, set a workers visited approximately 6 to 8 people. At the

patient-centered agenda, challenge received wisdom, day care center for people with memory and cogni-

and can generate new hypotheses. Because in this tive problems, 8 to 10 people attended on the two

study we aimed to explore the factors that influenced main days when the first author visited. Finally,

peoples decision- and choice-making processes when between 40 and 50 people attended the three lun-

using or anticipating the use of care services, it was cheon clubs hosted at the community center.

also interesting to note Donalds (1998) work, which Following the initial visits to each center, the follow-

suggests that narratives can provide insights into the ing numbers of people gave their consent for the par-

effects of culture and history on individuals views of ticipant observation phase of the study: 25 people from

illness, care, and treatment. the African Caribbean service, 10 people (or their car-

In the context of this study, narratives were initially ers) from the service for people with memory/cognitive

seen as the gathering of peoples stories based on their problems, and a total of 31 people from the luncheon

lived experience and their use or nonuse of health and clubs. The varying numbers of participants providing

social care services. At the outset it was envisaged consent reflected the overall size of each service. A

that narratives would be recorded in some way and list of who had given consent was kept by the first

fed back, so that key claims could be checked with author every time she visited a center. No records

each person. However, the structure and form of the were made of conversations for which signed consent

narratives was not predetermined. Instead, reflecting had not been obtained. When general observations

the constructivist methodology that framed the study, were made, care was taken to ensure that people who

it was thought more fitting to explore how narrative had not given consent were not identified. Even when

stories should be presented once some stories had written consent had been obtained previously, this

been collected. was rechecked with individuals each time the first

author visited the study sites. When selecting people

Participants to be interviewed, each individual was asked to sign

The study was undertaken at three study sites: a a consent form indicating they were agreeable to a

community support and outreach service for Black tape recording being made. A total of 24 people were

African Caribbean elders, a day care and community interviewed (8 from each study site).

outreach service for older people with memory or

cognitive problems, and a community center that

From Interview to Narrative

hosted luncheon clubs on three separate days. These Following the interviews, we wanted to give par-

settings were identified and chosen as reflecting the ticipants the opportunity to reflect more critically on

Downloaded from qhr.sagepub.com at NORTH CAROLINA STATE UNIV on April 7, 2015

1276 Qualitative Health Research

the information they had shared. The notion of taking Although Mr. Smiths response in the interview

back the full interview transcripts was rejected, as revealed why he had agreed to accept home care, the

evidence suggests that participants find these diffi- researcher noted the following in the narrative:

cult to read and too information-rich, and as a conse-

quence they can often focus more on grammar or Mr. Smith told me that he has regular home carers

syntax than content (Bornat, 2002; Clarke, 2000; most mornings, lunchtimes and evenings. When the

Echevarria-Howe, 1995; Northway, 1998). In looking regular home carers come to see him Mr. Smith

finds the service is good. Unfortunately, however,

for alternative ways of taking data back to participants,

he has told me that sometimes the home carers dont

we noted the work of Ellis and Bochner (2000), who

turn up.

make a case for personal narratives being a means for

researchers to enable participants to feel the truth of When the researcher asked Mr. Smith about this in

their story and become coparticipants, engaging with the interview, he said,

their story morally, emotionally, aesthetically, and

intellectually. Following this initial lead, the first Sometimes they dont turn up, and sometimes theyre

author then reviewed the literature for additional late and sometimes theyre early. You have some

guidance on the use and construction of narratives in [that] are better than others, you know, but some-

a health and social care research project. times they come early and that sort of thing and I

mean for teatime, sometimes they come at 3:00. Well

I mean Ive only just had my lunch, you know, and I

Constructing Narrative Summaries

have to refuse them. So by and large its some are

Ellis and Bochner (2000) recommend that as better than others.

research text, a narrative should be a story of the indi-

viduals experience written free from academic jar- When the researcher returned to share the narra-

gon or abstracted theory. To construct narratives and tive with Mr. Smith, he confirmed that in the main he

holistically analyze field texts such as transcripts, was happy with the home care service he received,

documents, and observational field notes it is there- but he accepted and continued to use the service pri-

fore suggested that researchers must read, reread, and marily because it enabled him to stay in his own

sequence the raw data until it goes beyond descrip- home, even though it did not always fit his personal

tion and thematic development, until the researcher and domestic schedules.

can understand the lived experience of the person

telling their story (Ollerenshaw & Cresswell, 2002). Results

The first author, supervised by the second and third

authors, therefore started the narrative constructions The final narratives were a summary of the first

by reading the transcripts of interviews in conjunc- authors conversations with participants, recorded in

tion with the notes made in the field during the field notes or interviews. Although some direct

participant observation phase of the study. quotes were used, these were carefully chosen to

For example, one man from the luncheon club highlight a particular point. Participants were asked

network (Mr. Smith) told the first author (hereafter to read and comment on the narrative summaries.

referred to as the researcher) that he had been receiv- Notes were made of any comments and any correc-

ing home care support for approximately 8 years. tions required. Each participant was then offered a

When the researcher spoke to him about his deci- copy of the final version of his or her narrative. Using

sion to use home care, he explained that the hospi- the narratives as part of a hermeneutic process proved

tal had suggested this service after he had been in to be useful in relation to

hospital for 5 or 6 weeks following a slight stroke.

The researcher then noted in her field diary that 1. facilitating commentaries by participants on a struc-

when she interviewed Mr. Smith, she wanted to ask tured summary of the information they had shared.

if he minded having home care. In the interview 2. identifying the factors participants indicated affected

Mr. Smith said, their decision- and choice-making processes when

using or contemplating using care services.

No. No I didnt mind, no. Well I preferred it rather 3. identifying the influence of life experiences in rela-

than going into a nursing home and that. Its far bet- tion to decision- and choice-making processes that

ter than going in a nursing home. I prefer it. might not have been immediately obvious.

Downloaded from qhr.sagepub.com at NORTH CAROLINA STATE UNIV on April 7, 2015

Tetley et al. / Narratives and Decision-Making Processes 1277

4. fostering a more holistic perspective that drew on that on the fourth occasion he had called the pension

the formal interview material and the notes made office and was told that the pen he had been using was

during participant observation in each setting. not dark enough. Harry went on to say that despite

5. providing feedback to participants concerning the this difficulty it had been worth the effort, as he was

value of the information they had shared. now 100 a week better off. He was so pleased with

6. raising empowerment and ethical issues.

this outcome that he showed the researcher his pen-

sion book and was happy to talk about his finances

Facilitating Commentaries by Participants something many of the other participants were

When the narrative summaries were returned to reluctant to do. After reading and commenting on the

participating individuals, this often generated further narrative, Harry said that he had not realized that he

discussion. For example, some participants gave had told the researcher so much, but he was pleased

updates about their current respective situation. When that someone had taken an interest in him.

Mrs. Rodgers (from the African Caribbean support In addition to generating comments on the fidelity

service) was interviewed she described how she had of the narratives, some participants also said they had

applied for aids and adaptations to her bathroom enjoyed reading their stories. Indeed, after reading

when she was struggling at home during her illness her narrative, Mrs. James from the African Caribbean

with breast cancer. A note had been made about this day center hugged the researcher and said she could

in her narrative, which then prompted her to explain not have wished for anything better. She took a copy

that someone from the Aids and Adaptations Service of her narrative home and said she was going to

had recently fitted a support rail around her toilet and frame it. For Mrs. James, the experience had evi-

given her a board to fit across the bathtub (seat) to dently contributed to a sense of pride and an affirma-

help her get into the bath. She said that she did not tion of her personal identity.

really need these anymore, but she had them fitted Identifying Decision- and

anyway in case she needed them in future.

Choice-Making Influences

During the construction of the narrative for Harry,

from the luncheon club, it had been noted that his Although a more detailed analysis of the inter-

decision to buy an electric scooter to help him get views was conducted to explore decision- and choice

around was of particular interest, because this had in making in relation to the use of care services, the

turn led him to apply for a ramp to be fitted to the step narrative summaries also highlighted tentative issues

outside his house. On the day the researcher took for discussion when the researcher returned to par-

Harrys narrative back to him, she was surprised to see ticipants in the study. For example, Mrs. James

that the new path and ramp were being fitted by local explained that she was cared for by her daughter. It

contractors. Harry said that when he got the letter was noted in the narrative that

about the work, so soon after the researcher had last

visited him, he wondered if she had managed to get Her daughter, Nadine, does most of the housework

things speeded up. The researcher said she had not, and laundry. Mrs. James and her daughter do the food

shopping together and get a taxi back home. Because

and explained that an occupational therapy colleague

Nadine lives with Mrs. James they dont get any help

had warned her that anyone trying to speed up the

with care, they also dont claim any benefits. Mrs.

process of fitting a ramp on the grounds of deteriorat- James told me that they had been advised that Nadine

ing health could actually cause delays. Harry said that could claim the attendance allowance but when they

he could see that if they thought he might die sooner saw the application and the detailed information that

rather than later, then they would not see the need to they would have had to provide they didnt apply.

do the work; he laughed at this.

Because the narrative described the problems This enabled the researcher to check with Mrs. James

Harry had experienced in applying for an adaptation about whether filling out paperwork had proven to be

to the pavement, it prompted him to recount his recent a barrier to applying for benefits. She indicated that

difficulties in applying for pension credit. Harry this had indeed been the case.

described how he had been made to complete the The narratives also worked well with people from

application form four times. He explained that he had the centers for dementia care. For example, during

bought a black pen especially to complete the form, her initial meetings, the researcher had become aware

but each time the form was returned. He explained that one of the women (Doreen) had refused to go

Downloaded from qhr.sagepub.com at NORTH CAROLINA STATE UNIV on April 7, 2015

1278 Qualitative Health Research

back to a social services day care center to which she move to a nursing home could be regarded as a fait

had initially been referred. In the narrative, the accompli (Nolan et al. 1996):

researcher noted that she wanted to interview Doreen

because Doreen had tried another day care service for I asked Mrs. Taylor about her health problems and she

people with memory problems, and had not enjoyed said that she didnt really know what had happened

it. When she stopped using this particular service she with her legs. She knew she had had problems with the

veins in her feet, she couldnt stand up for long and

moved to the dementia charity day center. More spe-

was getting cramps. At first she had her toes ampu-

cifically, the researcher wanted to find out why she

tated and then her foot. When she first went home

did not enjoy the first day care center, but particularly from hospital she was able to walk in her flat with a

enjoyed the day care center she was now attending. In frame. She had support from home care to clean and

the narrative, the researcher wrote: look after her and had a commode, but she was still

able to cook for herself. She also had the district nurse

Doreen was referred to a social service day care visit twice a day to give her insulin. After her amputa-

center from the NHS assessment center to which she tions the wounds took a long time to heal because of

had originally been referred. She attended for a her diabetes. Since her last admission to hospital she

while but didnt enjoy it as she said that the staff was unable to look after herself, which is how she

didnt interact much with the people who attended came to be moved into the nursing home where I met

the center. Jane [Doreens daughter] said, her. When I interviewed Mrs. Taylor she told me,

It wasnt a patch on [the NHS day center], you see. The doctors in the [hospital] say they would send me

But we said, Well stick it out and try it, and she did in this home. I didnt even know about it. He sent me

do, and then she got used to it after a while. And and I think they pay, they pay the fee for the, I think

occasionally she said, Oh we dont do anything, they in December, January and February, two months.

just all sit at one end gossiping, the staff, and leave us They say erm the time of how I have to start paying

to gossip between us. She wasnt very happy. And for myself now, is March. But thats why I, thats

we said, Well theres no other alternative really. why he came in here he was fixing up the social

Doreen then became ill and said she didnt want to people, to get the money.

go back to the social services day center, and so

Jane had to start looking for an alternative. Jane told At the end of the narrative the researcher noted that

me that finding an alternative day care service for Mrs. Taylor was able to confirm that she had not been

people with dementia was difficult. She also said given any choice about the move to a nursing home.

that when she had been looking for alternative day She claimed she was moved to the home from hospital

centers and luncheon clubs near to where Doreen and had stayed there. The use of narratives therefore

lives, she was put off some of them because she felt provided a mechanism for verifying the factors shap-

the people there were much older than her mum. ing older peoples decision making in this context.

This prompted Jane to contact the dementia charity

again to see if they could help them.

The Influence of Life Experiences

Through the narrative the researcher was therefore When the researcher was writing up the narrative

able to combine material from the observations and summaries the main purpose had been to provide

informal conversations with Doreen and her daugh- people with an easy-to-read synopsis of the informa-

ter, Jane, at the day center, with quotations from the tion they had shared with her. However, reflecting

interview to cross-validate the issues that appeared the work of Studs Terkel on the Great Depression

to have affected their decision making in relation to (Terkel, 1970), the researcher became aware when

day care. people told their stories that key historical events

Other narratives enabled the researcher to estab- had often affected their decision- and choice-making

lish how people had been involved in decisions about processes. One example of this can be seen in the

the services they received. While undertaking partici- interview with Mr. Smith, a 96-year-old man from

pant observation in the African Caribbean day center the luncheon club. The researcher made what was

and outreach service, the researcher accompanied a intended to be a light-hearted comment about his

worker when she visited an older woman who was long life and good health being related to the fact

in the process of moving into long-term care. The that he had never married. Although partly wishing

researcher noted in her field diary that the womans that she had not made this comment, his response to

Downloaded from qhr.sagepub.com at NORTH CAROLINA STATE UNIV on April 7, 2015

Tetley et al. / Narratives and Decision-Making Processes 1279

the question made her think about the influence of experiences at this time also affected his political

peoples lived experiences through difficult times on views. He embraced left-wing political activities and

their decision making: became a union shop steward.

Researcher (R): I was surprised when you said you Enabling a More Holistic Perspective

were 96.

Greenhalgh and Hurwitz (1999) have argued that

Mr. Smith (Mr. S.): Well as I say, Im fortunate in narratives enable practitioners and researchers to

that respect I think. understand people more holistically because they

R: Do you think youve survived [so] well because provide a meaning and context to the persons

you didnt marry? story. As the researcher reviewed the narratives she

found many examples of this. In one instance a

Mr. S.: I dont know, I think I made a mistake in not

woman from the luncheon club network told her

marrying, actually. I went through the early 30s and

about her painting and embroidery. In her narrative,

late 20s through the depression. Well I went through

that lot and that was it, that period. And then I used the researcher wrote:

to read a lot, go to the library; thats where I learnt

my photography. I used to take books out from the Violet has enjoyed painting and embroidery over the

library. I read every book in the library in photogra- years, and there were some wonderful examples of

phy. Some I had four or five times I used to take her work on the walls of her flat. Violet told me how

them out. And thats where I learnt it. she started painting on recommendation from a regu-

lar customer who brought his disabled daughter for

clothes to the department store where she worked.

At the time, this comment did not appear to be of

Violet had been off work with what she called ner-

particular importance. However, as the researcher vous exhaustion. I used a quote from the interview in

prepared the narrative summary she suddenly saw the narrative to illustrate how she explained how other

this statement in another light and added the follow- people influenced her decisions to try new things:

ing comment:

He said, Now I want you to start painting. I said,

The issue of the economic depression of the 1920s You must be joking. He said, No Im not. I said,

and 30s affecting peoples decision making was of I cant paint for toffee, I said, I cant even draw

interest as my father-in-law, who is slightly younger for toffee in any case, so I said, Its no use me

than Mr. Smith, was profoundly affected by his wasting money on that. He said, You are going to

fathers unemployment during this time. Having learn how to paint. So I said, Oh. And his wife

lived through the depression has affected his deci- stood there and she was grinning like a Cheshire cat,

sion making with regard to marriage, money, work, you know. When it came to with talking to him, he

and taking risks in life. This highlighted to me the used to teach people like his daughter, that was his

importance of understanding someones biography job, teaching them to paint and everything. So he

in the context of the historical time that they lived. said, I think you could do it. So he said, I will tell

you what, get a piece of brown paper, and some

After her return visit the researcher added to the newspaper, put them on the floor and get some paint,

narrative: distemper or anything you want, put your brush in

and just literally throw it on the paper. I said,

I checked this out on my return visit to Mr. Smith by Youre having me on [teasing me], arent you? He

asking him if I was right to think that the economic says, I am not. He says, Thats what you want,

depression had had a profound effect on him. He and he said, You will find out it will help you so

said it had because he was unemployed and couldnt much. He said, Will you do it for me? So I said,

get work for a long time. During this time he was Alright. I didnt know whether to or not.

sent on a training course and got a few weeks work

but this finished after a few weeks. He said they The researcher also wrote in her narrative:

coped as a family because his brother worked as a

miner and his mother got a war widows pension. During the time that I met with Violet at the luncheon

Mr. Smith reiterated that it was during this time that club she shared some of her health problems with

he visited the library and learnt about photography. me. She also told me how her GP [general practitio-

Whilst he was unemployed he earned some money ner] had influenced her and her husbands decision

by winning prizes for his photographs and taking to move to a flat when they were both very ill. By

wedding photographs. Mr. Smith told me that his interviewing Violet and constructing her narrative

Downloaded from qhr.sagepub.com at NORTH CAROLINA STATE UNIV on April 7, 2015

1280 Qualitative Health Research

I was able to check out how the role of others influ- Mr. Morris refuse his dinner she also pushed her

enced peoples decision-making processes. plate away. I feel that he gives others the confidence

to say no.

The influence of professional and social networks

in Violets life was interesting, as research studies Indeed, Jerromes (1992) study of older people and

have found that social networks and social support their social networks found that elderly peers can act

can help older people maintain good health (Glass, as positive role models for their contemporaries, pro-

et al. 2000). Moreover, a review of the literature viding opportunities for self expression, a sense of

revealed that a combined use of professional support security, a supportive network, a chance to confront

and social relations were particularly important to some of the ambiguities and losses of ageing (p. 53).

women, and positively influenced womens health In another instance, a woman at the luncheon club

behaviors (Hurdle, 2001). network shared some difficult and painful memories.

Establishing a more holistic understanding of the In the narrative, the researcher wrote:

individual was important for the next stage of the

study, because the researcher planned to undertake a I would really like to thank Laura for sharing her

experiences with me. My time with her gave me some

more detailed analysis of the individual transcripts. It

powerful and unexpected insights into peoples expe-

was evident that the second stage of the analysis

riences of applying for care and services in later life.

would require breaking down the content of the inter-

views into a range of codes and categories. The Laura had shared an experience from her life that

researcher compared the value of the narratives in could not be discussed in a public forum because of

relation to the literature presented earlier in this arti- the associated stigma. Without Lauras openness and

cle. As Donald (1998) suggested, the narratives had honesty, it would not have been possible to under-

indeed provided insights into the effects of culture, stand how hidden and difficult stories can influence

history, and people on individuals views of illness decision- and choice-making processes. This finding

and care. Supporting the views of Greenhalgh and is also reflected in the work of East (1999), who

Hurwitz (1998), the narratives also helped to provide found that women are often negatively affected in

a more integrated understanding of peoples experi- their abilities to seek welfare and help by hidden bar-

ences that took into account important biographical riers related to domestic violence, childhood experi-

contexts and their meaningfulness. ences of victimization, mental health issues (addiction

and depression), and low self-esteem. Although the

Enabling Feedback of the Value narratives proved to be a useful tool for sharing the

of Shared Information interview material with participants and for starting

the formal analysis process, there were issues about

By using narratives, the researcher was able to

their use that required further consideration.

explain to people the value of the information they

had shared with her. Regarding one of the Black male Empowerment and Ethics

participants, Mr. Morris, the researcher wrote:

After reading her narrative, one participant said she

I have enjoyed meeting Mr. Morris; he has always felt she had said things that she should not have said.

made me welcome and we seem to have enjoyed She asked that the narrative and all corresponding

each others company. Mr. Morris has a strong char- interview data be destroyed. This was done. A similar

acter and knows what he likes and wants. I like the experience was encountered by Clarke, Hanson, and

fact that he wont accept poor quality care services Ross (2003), who found that when introducing a bio-

and challenges people when he isnt happy and graphical approach to care, one woman had been

stands up for himself. I wish more older people had

prepared to talk about her past but after a while she

the courage that he has. Since he has been in the

had become upset, as she did not want to recall pain-

nursing home, Mr. Morris has made it clear to the

staff when he hasnt been happy with things, such as ful past experiences and refused to participate any

not having enough warm bedding on his bed and further in the project. The request to destroy all the

being served food that he doesnt like. I have inter- interview data about this woman raises the important

viewed a lady (Mrs. Taylor) who is also from the issue of ethics. In this particular instance, the adopted

African Caribbean community in the same home as approach (constructivism). coupled with a strong

Mr. Morris. Mrs. Taylor told me that when she saw moral imperative about the importance of participants

Downloaded from qhr.sagepub.com at NORTH CAROLINA STATE UNIV on April 7, 2015

Tetley et al. / Narratives and Decision-Making Processes 1281

owning their narratives, propelled the researcher These preliminary insights provided a useful start-

down a path where consent by and respect for par- ing point for the third stage of the study, which was

ticipants was pivotal. Put another way, this was about to be an inductive analysis of the data. Moreover, it

the maintenance of high ethical standards and a com- was hoped that this final stage would lead to the

mitment to research with people rather than research development of an explanatory framework of the fac-

on people (Heron & Reason, 2001; Reason, 1994). tors that older people themselves had identified as

The request to destroy material was of additional affecting their decision-making processes concerning

interest, because she had struggled to include pain- health and social care services. The preliminary find-

ful or very personal information in the narrative in ings were therefore particularly valuable. Lincoln and

as sensitive a manner as possible. Indeed, Heath Guba (1985) argue that the first phase of theory

(1998) advises that when people have experienced development, prior to the use of qualitative data

pain, humiliation, violence, and chronic illness, nar- reduction and analysis procedures, should be under-

ratives can help them rediscover a sense of self- pinned by a process where there is a development of

worth and dignity. working hypotheses, concepts, and hunches. They

The examples from the narratives given earlier illus- suggest that these can then be used to develop themes

trate how the researcher tried to reflect back to partici- and categories, and can help explain relationships

pants the value of their individual contributions to the between the final concepts that emerge.

research, consulting each individual carefully about the As we reflected more broadly on the use of narra-

content and construction of each narrative. For exam- tives within a constructivist methodology, we were

ple, one woman had shared a very difficult issue about also able to see other important contributions that they

her past experiences of health care. Because these had made to the study. As noted previously, hermeneu-

experiences still influenced her view of care and ser- tics is important within the constructivist methodol-

vices, it was agreed that it would be best to omit any ogy because constructivism is fundamentally based on

details relating to this issue from the narrative. Despite interpretive principles. Geanellos (1998), on the other

all these efforts, it must be acknowledged that if the hand, argues that a danger of hermeneutic philosophy

aim of using narrative in research and practice is to is that it does not require the interpreter to check what

work in partnership with participants, the right to cen- the person who told the original story meant. Indeed,

sor information provided, or to request its destruction, Gadamer (1990) argued that hermeneutics requires the

must lie with the person whose story is central to the interpreter to grasp the meaning and significance that

narrative (Brody, 1994; Hudson-Jones, 1999). is transmitted from the original story or text. As the

first author was personally committed to participatory

research, she was not prepared to accept that her inter-

Discussion and Conclusion pretation of any data gathered during the course of the

study would be adequate. The narratives therefore

The use of narratives in this study enabled us to became a data-handling process that enabled her to

gain a preliminary understanding of the factors that share her interpretations of peoples stories and expe-

had influenced peoples decision- and choice-making riences with individuals and seek their feedback.

processes when using or contemplating the use of It has been argued that the concept of philosophi-

care services. These included: cal hermeneutics was developed to advance an onto-

logical argument that peoples understandings of their

experiences of struggling to manage their everyday lives and existence are not based only on the here

care needs and now, but also by history and culture (Gadamer,

the role of personal factors (including resilience, 1977; Guba & Lincoln, 1989; Parsons-Suhl, Johnson,

alternative forms of support, and social networks)

McCann, & Solberg, 2008). The use of narratives

individual values and norms

within the hermeneutic circle was therefore of addi-

the influence of biographical journeys, life history,

faith, loneliness, and bereavement tional value, as illustrated in this article. Narratives

individual responses, when faced with bureaucratic enabled participants to make sense of their own expe-

processes riences in the context of the study that was being

the availability of acceptable service alternatives undertaken. They also enabled the researcher to relate

system pressures constraining choice and control in one aspect of a persons life to their whole existence,

decision making and visa versa.

Downloaded from qhr.sagepub.com at NORTH CAROLINA STATE UNIV on April 7, 2015

1282 Qualitative Health Research

Despite the advantages that the use of narratives practice of social gerontology (pp. 117-134). Buckingham,

brought to the study, the challenges associated with UK: Open University Press.

Brody, H. (1994). My story is broken; can you help me fix it?

this process must be acknowledged. As we have

Medical ethics and the joint construction of narrative.

demonstrated in this article, the use of narratives is Literature and Medicine, 13(1), 79-92.

not a simple process. The development of the narra- Brown, L. D. (2008). Making it sane: Using narrative to explore

tives was time consuming; data from field notes and theory in a mental health consumer-run organization.

interviews were revisited and used to create 24 indi- Qualitative Health Research, 18, 1673-1686.

vidual narrative summaries that varied between 4 and Bytheway, B. (2003). Everyday living in later life. London:

Centre for Policy on Ageing.

15 pages in length. The researcher then revisited 22 Clarke, A. (2000). Using biography to enhance the nursing care

of the 24 participants (2 were not available because of older people. British Journal of Nursing, 9(7), 429-433.

of changes in their circumstances) to allow them to Clarke, A., Hanson, E. J., & Ross, H. (2003). Seeing the person

read and comment on their narrative summaries. The behind the patient: Enhancing the care of older people using a

construction of the narratives was challenging, biographical approach. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 12(5),

697-706.

because the summaries included personal informa-

Department of Health. (2006a). Our health, our care our say:

tion that could remind the participants of difficult life A new direction for community services. London: Author.

events. Efforts were made to ensure that the content Department of Health. (2006b). A new ambition for old age: Next

of the narratives was a balance of personal, pleasur- steps in implementing the National Service Framework for

able, and, where necessary, more sensitive informa- Older People. London: Author.

tion. This process could be criticized, because the Donald, A. (1998). The words we live in. In T. Greenhalgh &

B. Hurwitz (Eds.), Narrative based medicine: Dialogue and

initial interpretations of the data were made by the discourse in clinical practice (pp. 17-28). London: BMJ Books.

researchers. The fact that the narratives were well East, J. F. (1999). Hidden barriers to success for women in wel-

received by all but 1 participant suggests that the fare reform. Families in Society, 80(3), 295-304.

decisions and processes used had created narrative Echevarria-Howe, L. (1995). Reflections from the participants:

summaries that were accurate and, in most cases, The process and product of life history work. Oral History,

23(2), 40-46.

acceptable and authentic.

Ellis, C., & Bochner, A. P. (2000). Autoethnography, personal

To conclude, although the construction and use of narrative, reflexivity: Researcher as subject. In N. K. Denzin

narratives within the inquiry process was time con- & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research

suming, their use within the hermeneutic circle pro- (2nd ed., pp. 733-768). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

vided a practical tool for feeding back qualitative data Engebretson, J., & Littleton, L. Y. (2001). Cultural negotiations:

gathered during the course of the study. More specifi- A constructivist-based model for nursing practice. Nursing

Outlook, 49(5), 223-230.

cally, as we worked through the process we began to Fudge, N., Wolfe, C. D. A., & McKevitt, C. (2007). Involving older

recognize that it was the combined use of narratives people in health research. Age and Ageing, 36(5), 492-500.

and constructivism that enabled us to understand more Gadamer, H.-G. (1977). Philosophical hermeneutics (D. E. Linge,

fully how peoples ontological constructions influ- Trans.). Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

enced their decision- and choice-making processes Gadamer, H.-G. (1990). The universality of the hermeneutical

problem (D. Linge, Trans.). In G. Ormiston & A. Shrift (Eds.),

when using, or contemplating the use of, health and

The hermeneutic tradition from Ast to Ricoeur (pp. 147-158).

social care services. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

Geanellos, R. (1998). Hermeneutic philosophy. Part 1:

References Implications of its use as methodology in interpretive nursing

research. Nursing Inquiry, 5(3), 154-163.

Appleton, J. V., & King, L. (1997). Constructivism: A naturalistic Glass, T. A., Dym, B., Greenberg, S., Rintell, D., Roesch, C., &

methodology for nursing inquiry. Advances in Nursing Berkman, L. F. (2000). Psychosocial intervention in stroke.

Science, 20(2) 13-22. Families in recovery from stroke trial (FIRST). American

Atkin, K. (1998). Ageing in a multiracial Britain: Demographic, Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 70(2), 169-181.

policy and practice. In M. Bernard & J. Phillips. (Eds.), The Greenhalgh, T., & Hurwitz, B. (1998). Narrative based medi-

social policy of old age. (pp. 163-182). London: Centre for cine: Dialogue and discourse in clinical practice. London:

Policy on Ageing. BMJ Books.

Boote, J., Telford, R., & Cooper, C. (2002). Consumer involve- Greenhalgh, T., & Hurwitz, B. (1999). Narrative based medicine:

ment in health research: A review and research agenda. Health Why study narrative? British Medical Journal, 318, 48-50.

Policy, 61(2), 213-236. Guba, E. G., & Lincoln, Y. S. (1989). Fourth generation evalua-

Bornat, J. (1999). Biographical interviews: The link between tion. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

research and practice. London: Centre for Policy on Ageing. Health and Social Care Change Agent Team. (2004) Avoiding and

Bornat, J. (2002). Doing life history research. In A. Jamieson & diverting admissions to hospital: A good practice guide.

C. Victor (Eds.), Researching ageing and later life: The London: Department of Health.

Downloaded from qhr.sagepub.com at NORTH CAROLINA STATE UNIV on April 7, 2015

Tetley et al. / Narratives and Decision-Making Processes 1283

Heath, I. (1998). Following the story: Continuity of care in gen- Northway, R. (1998). Engaging in participatory research: Some

eral practice. In T. Greenhalgh & B. Hurwitz (Eds.), Narrative personal reflections. Journal of Learning Disabilities for

based medicine: Dialogue and discourse in clinical practice Nursing and Social Care, 2(3), 144-149.

(pp. 83-93). London: BMJ Books. Nygren, B., Norberg, A., & Lundman, B., (2007). Inner strength

Heron, J., & Reason, P. (2001). The practice of cooperative as disclosed in narratives of the oldest old. Qualitative Health

inquiry: Research with rather than on people. In Research, 17, 1060-1073.

P. Reason & H. Bradbury (Eds.), Handbook of action research Ollerenshaw, J.-A., & Cresswell, J. W. (2002). Narrative research:

(pp. 144-154). London: Sage. A comparison of two restorying data analysis approaches.

Hogarth, S., & Marks, L. (1998). The golden narrative in British Qualitative Inquiry, 8(3), 329-347.

medicine. In T. Greenhalgh & B. Hurwitz (Eds.), Narrative Parsons-Suhl, K., Johnson, M. E., McCann, J. J., & Solberg, S.

based medicine: Dialogue and discourse in clinical practice (2008). Losing ones memory in early Alzheimers disease.

(pp. 140-148). London: BMJ Books. Qualitative Health Research, 18, 31-42.

Housley, W. (2000). Story, narrative and team work. The Reason, P. (1994). Participation in human inquiry. London:

Sociological Review, 48(3), 425-443. Sage.

Hudson-Jones, A. (1999). Narrative in medical ethics. British Ridge, D., & Ziebland, S. (2006). The old me could have never

Medical Journal, 318, 253-256. done that: How people give meaning to recovery following

Hurdle, D. E. (2001). Social support: A critical factor in womens depression. Qualitative Health Research, 16, 1038-1053.

health and health promotion. Health and Social Work, 26(2), Rodwell, M. (1998). Social work constructivist research. London:

72-79. Garland.

Jerrome, D. (1992). Good company: An anthropological study of Schwandt, T. A. (2000). Three epistemological stances for quali-

old people in groups. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. tative inquiry: Interpretivism, hermeneutics and social con-

Johnson, J. (2004). Writing old age. London: Centre for Policy structionism. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.),

on Ageing. Handbook of qualitative inquiry (2nd ed., pp. 189-213).

Joseph Rowntree Foundation. (2004). From welfare to well-being: Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Planning for an ageing society. York, UK: Author. Tanner, D. (2001). Sustaining the self in later life: Supporting

Kane, R. L., & Kane, R. A. (2001). What older people want from older people in the community. Ageing and Society, 21(3),

long-term care, and how they can get it. Health Affairs, 255-278.

20(6), 114-127. Terkel, S. (1970). Hard times. London: Allan Lane/Penguin Press.

King, L., & Appleton, J. V. (1999). Fourth generation evaluation Tetley, J., Haynes, L., Hawthorne, M., Odeyemi, J., Skinner, J.,

of health services: Exploring a methodology that offers equal Smith, D., et al. (2003). Older people and research partner-

voice to consumer and professional stakeholder. Qualitative ships. Quality in Ageing, 4(4), 18-23.

Health Research, 9, 698-710. Wainwright, S. P. (1997). A new paradigm for nursing: The

Koch, T. (1996). Implementation of a hermeneutic inquiry in potential of realism. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 26(6),

nursing: Philosophy, rigour and representation. Journal of 1262-1271.

Advanced Nursing, 24(1), 174-184. Wenger, G. C. (1999). Choosing to pay for care. Health and

Laughlin, R., & Broadbent, J. (1996). Redesigning fourth genera- Social Care in the Community, 7(3), 187-197.

tion evaluation: An evaluation model for the public-sector

reforms in the UK. Evaluation, 2(4) 431-451.

Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Josephine Tetley, PhD, MA, BSc (Hons), PGCE, RGN, is a

Beverly Hills, CA: Sage. senior lecturer at the Open University in Milton Keynes,

Mitchell, P., & Koch, T. (1997). An attempt to give nursing home Buckinghamshire, United Kingdom.

residents a voice in the quality improvement process: The chal-

Gordon Grant, PhD, MSc, BSc, is an emeritus professor of the

lenge of frailty. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 6(6), 453-461.

Centre for Health and Social Care Research at Sheffield Hallam

Nolan, M., Hanson, E., Grant, G., & Keady, J. (2007). User par-

University, Sheffield, United Kingdom.

ticipation in health and social care research: Voices, values and

evaluation. Maidenhead, UK: McGraw Hill/Open University Susan Davies, PhD, MSc, BSc, RGN, RHV, is an honorary

Press. reader at Sheffield University School of Nursing and Midwifery,

Nolan, M., Walker, G., Nolan, J., Williams, S., Poland, F., Sheffield, United Kingdom.

Curran, M., et al. (1996). Entry to care: Positive choice or fait

accompli? Developing a more proactive nursing response to

the needs of older people and their carers. Journal of For reprints and permission queries, please visit SAGEs Web site

Advanced Nursing, 24(2), 265-274. at http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav.

Downloaded from qhr.sagepub.com at NORTH CAROLINA STATE UNIV on April 7, 2015

You might also like

- ReflectionsDocument8 pagesReflectionsForce MapuNo ratings yet

- Disability, Work and Inclusion in Ireland: Engaging and Supporting EmployersDocument154 pagesDisability, Work and Inclusion in Ireland: Engaging and Supporting EmployersForce MapuNo ratings yet

- The Continuum of LTCDocument478 pagesThe Continuum of LTCForce Mapu100% (1)

- Gosta Esping-AndersenDocument374 pagesGosta Esping-AndersenForce MapuNo ratings yet

- Cultural Anthropology Methods: Using ANTHOPAC3.5anda Spreadsheet To Compute A Free'List Salience IndexDocument3 pagesCultural Anthropology Methods: Using ANTHOPAC3.5anda Spreadsheet To Compute A Free'List Salience IndexForce MapuNo ratings yet

- Pet Shop Boys Super PDFDocument11 pagesPet Shop Boys Super PDFForce MapuNo ratings yet

- Gay Men's Relationships Across The Life Course (2013)Document217 pagesGay Men's Relationships Across The Life Course (2013)Force Mapu100% (1)

- Gosta Esping-AndersenDocument289 pagesGosta Esping-AndersenForce MapuNo ratings yet

- Clases SocialesDocument9 pagesClases SocialesForce MapuNo ratings yet

- Why We Care About Care: An Online Moderated Course On Care EconomyDocument2 pagesWhy We Care About Care: An Online Moderated Course On Care EconomyForce MapuNo ratings yet

- The Increasing Use of Theory in Social Gerontology: 1990-2004Document8 pagesThe Increasing Use of Theory in Social Gerontology: 1990-2004Force MapuNo ratings yet

- 0148 9062 (94) 92857 6 PDFDocument1 page0148 9062 (94) 92857 6 PDFForce MapuNo ratings yet

- HuiDocument11 pagesHuiForce MapuNo ratings yet

- Culture As Consensus: Theory of Culture and Informant AccuracyDocument26 pagesCulture As Consensus: Theory of Culture and Informant AccuracyForce MapuNo ratings yet

- View This Journal Online At: Alkaloids U 0600 DOI: 10.1002/chin.201107207Document1 pageView This Journal Online At: Alkaloids U 0600 DOI: 10.1002/chin.201107207Force MapuNo ratings yet

- PinaDocument18 pagesPinaForce MapuNo ratings yet

- Recent Applications of Cultural Consensus TheoryDocument16 pagesRecent Applications of Cultural Consensus TheoryForce MapuNo ratings yet

- Web-Based Free Lists Comparable to Other ModesDocument15 pagesWeb-Based Free Lists Comparable to Other ModesForce MapuNo ratings yet

- LobosDocument21 pagesLobosForce MapuNo ratings yet

- 6195Document6 pages6195Force MapuNo ratings yet

- Quantifying Preferences for Long-Term Care Delivery ModesDocument8 pagesQuantifying Preferences for Long-Term Care Delivery ModesForce MapuNo ratings yet

- The Increasing Use of Theory in Social Gerontology: 1990-2004Document8 pagesThe Increasing Use of Theory in Social Gerontology: 1990-2004Force MapuNo ratings yet

- Willingness To Use A Nursing Home: A Study of Korean American EldersDocument8 pagesWillingness To Use A Nursing Home: A Study of Korean American EldersForce MapuNo ratings yet

- PinaDocument18 pagesPinaForce MapuNo ratings yet

- Who Wants Long-Term Care in KoreaDocument6 pagesWho Wants Long-Term Care in KoreaForce MapuNo ratings yet

- Health Affairs: For Reprints, Links & Permissions: E-Mail Alerts: To SubscribeDocument7 pagesHealth Affairs: For Reprints, Links & Permissions: E-Mail Alerts: To SubscribeForce MapuNo ratings yet

- Nie BoerDocument9 pagesNie BoerForce MapuNo ratings yet

- Instituto Nacional de Salud Pu Blica: Innovations in Graduate Public Health Education: TheDocument4 pagesInstituto Nacional de Salud Pu Blica: Innovations in Graduate Public Health Education: TheForce MapuNo ratings yet

- WardDocument11 pagesWardForce MapuNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5783)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Aashto PDFDocument48 pagesAashto PDFPrateek ChandraNo ratings yet

- Entrepreneurship Decision Making ProcessDocument2 pagesEntrepreneurship Decision Making ProcessDianne Laurice Magnaye RodisNo ratings yet

- Accounting Context: Tutorial 11Document4 pagesAccounting Context: Tutorial 11Wee Hao GanNo ratings yet

- Management Theory and PracticeDocument108 pagesManagement Theory and PracticeAytenew AbebeNo ratings yet

- Lecture1 - Politics and Planning in IndiaDocument18 pagesLecture1 - Politics and Planning in IndiaDevashree RoychowdhuryNo ratings yet

- Performance Appraisal of DoctorDocument8 pagesPerformance Appraisal of DoctorKathuria Aman0% (1)

- A Handbook of Transport Economics PDFDocument930 pagesA Handbook of Transport Economics PDFMiguel CudjoeNo ratings yet

- F2 - BPP PASSCARD (2016) byDocument209 pagesF2 - BPP PASSCARD (2016) bySumair KhalilNo ratings yet

- Economy Lecture HandoutDocument38 pagesEconomy Lecture HandoutEdward GallardoNo ratings yet

- Committee To Review Research On Police Policy and Practices Wesley Skogan and Kathleen Frydl, EditorsDocument336 pagesCommittee To Review Research On Police Policy and Practices Wesley Skogan and Kathleen Frydl, EditorsfaithNo ratings yet

- Reading 19Document8 pagesReading 19thuyngatran865No ratings yet

- MC 101 Management Concept and Organisational BehaviourDocument739 pagesMC 101 Management Concept and Organisational BehaviourHoàng NgọcNo ratings yet

- COMPRE REVIEWER FUNDA Lec and Lab AND ANAPHYDocument19 pagesCOMPRE REVIEWER FUNDA Lec and Lab AND ANAPHYNikka Aubrey Tegui-inNo ratings yet

- The Factors That Influence The Career Choices of Grade 12 HUMSS Students in MilDocument28 pagesThe Factors That Influence The Career Choices of Grade 12 HUMSS Students in MilJhellean CosilNo ratings yet

- SCHOOL HEADS' NEW NORMAL LEADERSHIP AND SUPPORT AMIDST PANDEMIC: ROLE TO TEACHERS' JOB SATISFACTION Authored By: Sherwin V. PulongbaritDocument25 pagesSCHOOL HEADS' NEW NORMAL LEADERSHIP AND SUPPORT AMIDST PANDEMIC: ROLE TO TEACHERS' JOB SATISFACTION Authored By: Sherwin V. PulongbaritInternational Intellectual Online PublicationsNo ratings yet

- Real Burger WorldDocument6 pagesReal Burger WorldNadeem BashirNo ratings yet

- Models of Policy Making and The Concept of Power in PolicyDocument15 pagesModels of Policy Making and The Concept of Power in PolicyLaurens BuloNo ratings yet

- Best Book For orDocument161 pagesBest Book For orsanthosh90mechNo ratings yet

- PATH Assessment® (Servant Leader) Result - GoodJobDocument4 pagesPATH Assessment® (Servant Leader) Result - GoodJobDilia NeicoNo ratings yet

- Evidence Based Practice A Concept AnalysisDocument7 pagesEvidence Based Practice A Concept Analysissana naazNo ratings yet

- Advantages and Disadvantages of Employee InvolvmentDocument6 pagesAdvantages and Disadvantages of Employee InvolvmentrazaalvNo ratings yet

- Department of Education: GRADE 7-10 (Junior High School)Document2 pagesDepartment of Education: GRADE 7-10 (Junior High School)Lenny Joy Elemento SardidoNo ratings yet

- Management Midterm Assignment by MEHDI SHAH RASHDIDocument4 pagesManagement Midterm Assignment by MEHDI SHAH RASHDIMuhram HussainNo ratings yet

- SSRN Id4380365Document30 pagesSSRN Id4380365Lucas ParisiNo ratings yet

- Basic Concepts Related To Social Work Definition and InterrelationshipsDocument17 pagesBasic Concepts Related To Social Work Definition and Interrelationshipscarmina pagoy100% (3)

- Authentic Youth Engagement Gid Jul101Document76 pagesAuthentic Youth Engagement Gid Jul101SlobodanNo ratings yet

- Quiz - CPM and PertDocument1 pageQuiz - CPM and PertAngel RavenNo ratings yet

- Dcom506 DMGT502 Strategic Management PDFDocument282 pagesDcom506 DMGT502 Strategic Management PDFArnel Olsim100% (2)

- English EssayDocument4 pagesEnglish EssayChantel GuyeNo ratings yet

- Nurse Education in Practice: Jaime L. Gerdeman, Kathleen Lux, Jean JackoDocument7 pagesNurse Education in Practice: Jaime L. Gerdeman, Kathleen Lux, Jean JackoChantal CarnesNo ratings yet