Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Stages and Aging in Moral Development - Some Speculations

Uploaded by

Alejandro GodoyOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Stages and Aging in Moral Development - Some Speculations

Uploaded by

Alejandro GodoyCopyright:

Available Formats

Looft, W . R. Children's judgments of age. Child De- Personality and socialization.

New York: Academic

velopment, 1971, 42, 1282-1284. (a) Press, 1973.

Looft, W . R. Perceptions across the life span of im- Neugarten, B. L. Adult personality: A developmental

portant informational sources for children and adoles- view. Human Development, 1966, 9, 61-73.

c e n t s . Journal of Psychology, 1971, 7 8 , 2 0 7 - 2 1 1 . ( b ) Neugarten, B. L. (Ed.), Middle age and aging. Chicago:

Looft, W . R. Reflections on intervention in old age: Mo- Univ. of Chicago, 1968.

tives, goals, and assumptions. Gerontologist, 1973, 13, Neugarten, B. L., & Weinstein, K. K. The changing Amer-

6-10. (a) ican grandparent. Journal of Marriage & the Family,

Looft, W . R. Socialization and personality throughout 1964, 26, 199-204.

the life-span: An examination of contemporary psy- Patterson, G. R. Families: Application of social learning

chological approaches. In P. B. Baltes & K. W . Schaie to family life. Champaign, III: Research Press, 1971.

(Eds.), Life-span developmental psychology: Personality Pressey, S. L., & Pressey, A . D. "Insider" longitudinal

and socialization. New York: Academic Press, 1973. evaluations of institutional living. Proceedings of the

(b) 77th Annual Convention of the American Psychological

Looft, W . R., & Svoboda, C. P. Structuralism in cognitive Assn., 1969, 4, 729-730.

developmental psychology: Past, contemporary, and Pressey, S. L., & Pressey, A. D. Major neglected need op-

futuristic perspectives. In K. F. Riegel (Ed.), Structure, portunity: Old-age counseling. Journal of Counseling

Downloaded from http://gerontologist.oxfordjournals.org/ at Monash University on December 6, 2014

transformation, interaction: Developmental and histori- Psychology, 1972, 19, 362-366.

cal aspects. Basel: Karger, 1973. (in press) Rheingold, H. L. Infancy. International encyclopedia of

Lowenthal, M. F. Antecedents of isolation and mental ill- the social sciences. Vol. 7. New York: Crowell-Collier

ness in old age. Archives of General Psychiatry, 1965, & Macmillan, 1968.

12, 245-254. Rheingold, H. L. The social and socializing infant. In D.

Maccoby, E. E. Differential socialization of boys and girls. A. Goslin (Ed.), Handbook of socialization theory and

Paper presented at the meetings of the American Psy- research. Chicago: Rand McNally, 1969.

chological Assn., Honolulu, Sept., 1972. Riegel, K. F. Influence of economic and political ideology

Maddox, G . L. Retirement as a social event in the United upon the development of developmental psychology.

States. In B. L. Neugarten (Ed.), Middle age and ag- Psychological Bulletin, 1972, 78, 129-141.

ing. Chicago: Univ. of Chicago Press, 1968. Riley, M . W . Social gerontology and the age stratifica-

Maxwell, R. J., & Silverman, P. Information and esteem: tion of society. Gerontologist, 1971, I I , 79-87.

Cultural considerations in the treatment of the aged. Riley, M . W . , Johnson, M . E., & Foner, A . (Eds.), Aging

Aging & Human Development, 1970, I, 361-392. and society: Vol. 3: A sociology of age stratification.

McCandless, B. R. Childhood socialization. In D. A . New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 1972.

Goslin (Ed.), Handbook of socialization theory and re- Robertson, J., & Wood, V. Grandparenthood: A study of

search. Chicago: Rand McNally, 1969. role conceptions. Paper presented at the 23rd annual

McCandless, B. R. Adolescents: Behavior and develop- meeting of Gerontological Society, Toronto, Oct., 1970.

ment. Hinsdale, III: Dryden Press, 1970. Rosow, I. Social integration of the aged. New York:

Mead, G . H. Mind, self, and society. Chicago: Univ. of Free Press, 1967.

Chicago Press, 1934. Saltz, R. Aging persons as child-care workers in a foster-

Mead, M. Culture and commitment: A study of the gen- grandparent program: Psychosocial effects and work

eration gap. New York: Doubleday, 1970. performance. Aging & Human Development, 1971, 2,

Nardi, A . H. Autoperception and heteroperception of 314-340.

personality traits in adolescents, adults and the aged. Skeels, H. M. Adult status of children with contrasting

Unpublished doctoral dissertation, West Virginia Univ., early life experiences. Monographs of the Society for

1971. Research in Child Development, 1966, 31 (Whole No.

Nardi, A . H. Person perception research and the percep- 105).

tion of life-span development. In P. B. Baltes and K. Troll, L. E. Issues in the study of generations. Aging &

W . Schaie (Eds.), Life-span developmental psychology: Human Development, 1970, I, 199-218.

After reviewing the properties of the cognitive-developmental stage concept which, heretofore, has

been restricted in its use to child and adolescent development, adulthood stages for moral de-

velopment are considered. In addition to discussing aspects of adult development in regard to moral

Stages 5 and 6, an attempt is made to delineate a new Stage 7 which is unique to

advanced adulthood and involves adoption of a religious and cosmic perspective. This

new stage is related to Erikson's theory and suggests novel lines of "positive" adult and gerontological

inquiries in a life-span developmental and philosophical perspective.

Stages and Aging in Moral Development

Some Speculations

Lawrence Kohlberg, PhD1

In this paper the focus will be upon two re- valid distinction may be drawn between develop-

lated issues. The first issue is that of whether a ment and age-change in adulthood and old age.

The second issue is that of whether positive de-

I. Professor of Education & Social Psychology, College of Edu- , ,. r . i

cation, Harvard Univ., Cambridge 02138. velopment occurs in the years ot aging which

Winter 1973 497

are generally characterized by decrements in than do sociocultural and maturational concepts

biological functioning. A positive answer to both of stages. The cognitive structural model starts

questions seems required before a life-span ap- with the distinction between quality and quantity

proach becomes really interesting and useful in in age-related change. Most age-related changes

the study of aging. As an example, Erikson's are changes in qualitative (structural-organiza-

theory is a life-span model which represents old tional) aspects of responses. A related distinc-

age as potential development through a stage of tion to quantity-quality is competence-perform-

integrity versus despair, a development colored ance. Structural theories treat most quantitative

by experiences at all previous stages. This im- changes as changes in performance rather than

plies a distinction between stage-development changes in structural competence. As an exam-

and sheer age-change, and a distinction between ple, there are decrements in speed and efficiency

a positive qualitative developmental change of immediate memory and information process-

toward "integrity" and all the decremental be- ing with age, but such changes do not imply a

havior changes involved in aging. regression in the logical structure of the aging in-

Downloaded from http://gerontologist.oxfordjournals.org/ at Monash University on December 6, 2014

As far as I know, there is no hard evidence dividual's reasoning process. In general, structural

bearing on either of these issues with regard to theory does not treat any change as a change in

aging, but an attempt will be made to extrapo- structural competence unless the change is evi-

late from findings on adulthood moral stage-de- dent in a qualitatively new pattern of response.

velopment to raise the possibility of stage-de- Qualitative novelty involves the distinction be-

velopment in old age. tween form and content. A really new kind of

experience, a really new mode of response, is

The Cognitive-Developmental Stage Concept one that is different in its form or organization,

In raising these issues I am assuming a struc- not simply in the element or the information it

tural or cognitive-developmental conception of contains.

stage (e.g., Kohlberg, 1969, 1973) as distinct In summary, the kinds of age change relevant

from a conception of stage as "age-linked social to a stage model are restricted to those implied

role" or as "developmental task." Viewed as by the distinctions between quality and quantity,

"sociocultural role" or "developmental task" it competence and performance, and form and con-

is noncontroversial to discuss a "stage" of in- tent. In addition to focusing upon quality, form,

tegrity in aging. In the sociocultural conception, competence, a cognitive-developmental stage

a culture (responding, in part, to maturational concept has the following additional general

events) outlines a rough sequence of roles or characteristics (Piaget, I960):

tasks from birth to death, and adaptation to this 1I) Stages imply distinct or qualitative differences in

task sequence leads to age-typical personality structures (modes of thinking) which still serve the

changes. same basic function (e.g., intelligence) at various

Often opposed to such socioenvironmentally points in development.

(2) These different structures form an invariant se-

defined "stages" are biological-maturational quence, order or succession in individual develop-

stages. In the psychological realm, an example ment. While cultural factors may speed up, slow

would be the stages of classical psychoanalytic down, or stop development, they do not change

theory, psychosexual stages, defined by the bio- its sequence.

logical activation of a new organ. Such a direct (3) Each of these different and sequential modes of

thought forms a "structured whole." A given

biological model of stages is unlikely to postulate stage-response on a task does not just represent

adult stages. After early adulthood, biological a specific response determined by knowledge and

notions of development are notions of either familiarity with that task or tasks similar to it;

stabilization or decrement in biological function- rather, it represents an underlying thought-organi-

ing, rather than of new biological activation of zation.

(4) Stages are hierarchical integrations. Accordingly,

a structure or qualitative biological change in higher stages displace (or, rather, reintegrate)

a structure. The notion of biological decrement the structures found at lower stages.

can be combined with the sociocultural role con-

ception of stage to define distinctive aging roles The characteristics of stages just mentioned

and tasks, but this does not come to grips with while defined by structural theory, are amenable

the problem of development as posed by struc- to research examination. We can ask,

tural theories. Are there qualitative changes in adulthood forming an

invariant sequence in any sociocultural environment,

The cognitive-developmental or structural which form a generalized structured whole and which

model of stages involves both different theoreti- hierarchically relate to earlier qualitative developmental

cal postulates and a different research strategy change?

498 The Gerontologist

The research strategies used to answer these theory if it is not a manifest case of measurement

questions are very different from those usually error,

entailed in the study of aging. The questions

entail little in the way of establishing age norms Moral Stage Development in Adulthood

for different populations or disentangling age As an example of research proof of adulthood

from cohort from time from testing effects, stage-development, we may take our own work

Rather, they require the careful analysis of a on moral stages. That adult moral stages might

small number of longitudinal cases. The number exist is suggested by the fact that moral change

of cases required is not large. Piaget's three in- is clearly a focal point for adult life in a way

fants defined an invariant sequence of sensori- cognitive change is not. We do not need Erik-

motor intellectual stages which has since been son's studies of Martin Luther and Mahatma

shown to hold for the development of large num- Ghandi to know that the crises and turning points

bers of infants in very different environments, of adult identity are often moral. From Saint

Stages are not established by longitudinal analy- Paul to Tolstoy, the classic autobiographies tell

Downloaded from http://gerontologist.oxfordjournals.org/ at Monash University on December 6, 2014

sis of one's own children, but they are established us the dramas of maturity are the transformations

by fairly small numbers of cases testing the limits of the moral ideologies of men.

of a universal sequence by longitudinal study of While dramatic moral change occurs in adult-

a variety of types of people in a variety of en- hood, the question is whether such change is

vironmental settings. A single case of longitudi- structural stage-change. We do know that there

nal inversion of sequence disproves the stage are structural moral stages in childhood and ado-

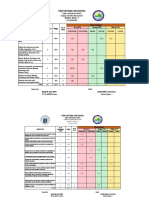

Table I. Definition of Kohlberg's Moral Stages.

I. Preconventional level

A t this level the child is responsive to cultural rules and labels of good and bad, right or wrong, but interprets

these labels in terms of either the physical or the hedonistic consequences of action (punishment, reward, exchange of

favors), or in terms of the physical power of those who enunciate rules and labels. The level is divided into the fol-

lowing two stages:

Stage I: The punishment and obedience orientation. The physical consequences of action determine its goodness

or badness regardless of the human meaning or value of these consequences. Avoidance of punishment and unques-

tioning deference to power are valued in their own right, not in terms of respect for an underlying moral order sup-

ported by punishment and authority (the latter being stage 4).

Stage 2: The instrumental relativist orientation. Right action consists of that which instrumentally satisfies one's own

needs and occasionally the needs of others. Human relations are viewed in terms like those of the market place. Ele-

ments of fairness, of reciprocity, and of equal sharing are present, but they are always interpreted in a physical

pragmatic way. Reciprocity is a matter of "you scratch my back and I'll scratch yours," not of loyalty, gratitude, or

justice.

II. Conventional level

A t this level, maintaining the expectations of the individual's family, group, or nation is perceived as valuable in

its own right, regardless of immediate and obvious consequences. The attitude is not only one of conformity to per-

sonal expectations and social order, but of loyalty to it, of actively maintaining, supporting, and justifying the order,

and of identifying with the persons or group involved in it. A t this level, there are the following two stages:

Stage 3: The interpersonal concordance or "good boynice girl" orientation. Good behavior is that which pleases

or helps others and is approved by them. There is much conformity to stereotypical images of what is majority or

"natural" behavior. Behavior is frequently judged by intention"he means well" becomes important for the first time.

One earns approval by being "nice."

Stage 4: The "law and order" orientation. There is orientation toward authority, fixed rules, and the maintenance

of the social order. Right behavior consists of doing one's duty, showing respect for authority, and maintaining the

given social order for it's own sake.

III. Postconventional, autonomous, or principled level

At this level, there is a clear effort to define moral values and principles which have validity and application apart

from the authority of the groups or persons holding these principles, and apart from the individual's own identification

with these groups. This level again has two stages:

Stage 5: The social-contract legalistic orientation, generally with utilitarian overtones. Right action tends to be de-

fined in terms of general individual rights, and standards which have been critically examined and agreed upon

by the whole society. There is a clear awareness of the relativism of personal values and opinions and a correspond-

ing emphasis upon procedural rules for reaching consensus. Aside from what is constitutionally and democratically

agreed upon, the right is a matter of personal "values" and "opinion." The result is an emphasis upon the "legal

point of view," but with an emphasis upon the possibility of changing law in terms of rational considerations of social

utility (rather than freezing it in terms of stage 4 "law and order"). Outside the legal realm, free agreement and

contract is the binding element of obligation. This is the "official" morality of the American government and constitu-

tion.

Stage 6: The universal ethical principle orientation. Right is defined by the decision of conscience in accord with

self-chosen ethical principles appealing to logical comprehensiveness, universality, and consistency. These principles

are abstract and ethical (the Golden Rule, the categorical imperative); they are not concrete moral rules like the

Ten Commandments. At heart, these are universal principles of justice, of the reciprocity and equality of human

rights, and of respect for the dignity of human beings as individual persons.

Adapted from Table I. Moral and Religious Education and the Public Schools, by Lawrence Kohlberg, in Religion and Public

Education, edited by Theodore R. Sizer. by Houghton Mifflin Co. Used by permission.

Winter 1973 499

lescence. These moral stages are defined in the first stage at which experiences of mutual

Table I. The stages have been demonstrated to affection, trust, and altruism are genuinely under-

meet the requirements of structural stages in the stood. These attitudes and ideas are first elabo-

following ways: rated in the interpersonal and moral realm and

(1) They are qualitatively different modes of thought only later used to structure relations of man to

rather than increased knowledge of, or internaliza- God, life, or the universe.

tion of, adult moral beliefs and standards. We have said that post-conventional or princi-

(2) They form an invariant order or sequence of de-

velopment. Fifteen-year longitudinal data on 50 pled morality is probably attainable only in early

American males in the age periods 10-15 to 25-30 adulthood and requires some experiences of

demonstrate movement is always forward and al- moral responsibility and independent moral

ways step-by-step. More limited 6-year longitudi- choice. We would expect that attainment of a

nal data on Turkish boys also indicate invariant

sequence as does cross-sectional age-data in many post-conventional faith would be an even later

cultures (Kohlberg & Turiel, 1974). construction. In this we see a parallel to Erik-

(3) The stages form a clustered whole. There is a gen- son's schema (see also Kohlberg, 1973). Erikson's

Downloaded from http://gerontologist.oxfordjournals.org/ at Monash University on December 6, 2014

eral factor of moral stage cross-cutting all dilem- ideal man has passed through his seventh stage

mas, verbal or behavioral, with which an individual of generativity and becomes an ethical man, an

is confronted (Kohlberg & Turiel, 1974).

(4) The stages are hierarchical integrations. Subjects

ideal corresponding to our State 6. There re-

comprehend all stages below their own and not mains for Erikson's man a task which is partly

more than one above their own. They prefer the ethical, but more basically religious (in the broad-

highest stage they comprehend (Rest, 1974). est sense of the term, "religious"), a task de-

With regard to adulthood stage-change, our fining an eighth stage whose outcomes are a

own longitudinal work does not extend beyond sense of integrity versus a sense of despair. The

the age of 32. However, the work does demon- problem of integrity is not the problem of moral

strate the existence of new stages developing integrity but of the integrity of meaning of the

only in adulthood. None of our longitudinal individual's life. Its negative side, despair, hovers

subjects attained Stage 5 before the age of 23 around the awareness of death. The concept of

(Kohlberg, 1973; Kohlberg & Turiel, 1974). For the self's integrity is psychological, but the con-

some, movement to this stage occurred later and cept of the integrity of the meaning of the self's

seemed to depend upon: (a) experiences of sus- life is philosophical or religious.

tained responsibility for the welfare of others; With regard to moral stages, our stages of

and (b) under conditions where the basis of this moral principle, even Stage 6, offers only an

responsibility can be both questioned and af- imperfect integration or resolution of the prob-

firmed on a universal human basis. An example lem of life's meaning. Even after attainment of

was Case 67, who was Stage 4 when interviewed a Stage 6 awareness of rational universal human

just after receiving his PhD at age 25. Four principles of justice, there remains the questions,

years later he was reinterviewed and was scored "Why be moral?", "Why be just in a universe

Stage 5. In the meantime he had served as a full of injustice?" Such a question, Job's ques-

captain in Vietnam and had the sort of experi- tion, cannot arise on a psychologically serious

ences of moral conflict around responsibility just level until a man has attained moral principles

mentioned. None of the young adults in our lon- and lived a life in terms of these principles for

gitudinal sample has yet reached our rare Stage a considerable length of time. The problem of

6, whose definition is based on data from other why be moral, of theodicy, is only one of the

adult samples. Presumably, however, it is a stage questions of meaning. Ultimately the answer to

attained, if at all, at a later age than Stage 5. the question, "Why be moral?" entails the ques-

tion, "Why live?" (and the parallel question,

Toward Adulthood Stage 7 "How face death?"). This, in turn, is hardly a

When we turn to the possibility of a positive moral question per se; it is an ontological or a

new stage in the aging, we must go beyond the religious one. Not only is the question not a

moral question, but it is not a question resolvable

notion of moral stages. Our notions start from

on purely logical or rational grounds as moral

pilot empirical work by Fowler (1973) suggesting

questions are. Nevertheless, I have used a purely

the existence of stages of "faith" or of "world

metaphorical notion of a Stage 7 as pointing to

outlook" which parallel the moral stages. We

some meaningful solutions to this question which

hypothesize that attainment of a given moral

are compatible with rational science and princi-

stage is a necessary but not sufficient condition

pled ethics (Kohlberg, 1971). The characteristics

for attainment of a parallel religious or ontolog- of all these Stage 7 solutions is that they involve

ical stage. As an example, our moral Stage 3 is

500 The Gerontologist

contemplative experience of nonegoistic or non- sists that: (a) the nature of each new stage had

dualistic variety. The logic of such experience is a definitely definable structure, a structure de-

sometimes expressed in theistic terms but it need fined by a logical system, and (b) each higher

not be. Its essential is the sense of being a part stage is logically, cognitively, or philosophically

of the whole of life and the adoption of a cosmic more adequate than the preceding stage and

as opposed to a universal humanistic (Stage 6) logically includes it. In contrast, Eriksonian the-

perspective. ory relies on psychological rather than on logical

The concept of such a Stage 7 is familiar, of or moral philosophical accounts of the way in

course, both in religious writing and in the classi- which each stage brings new "strength" or "wis-

cal metaphysical tradition from Plato to Spinoza. dom" to the individual. As a result, in its moral

In most accounts the movement starts with de- and religious aspects, Erikson's account is more

spair. Such despair involves the beginning of a culturally relative (and relative to individual life

cosmic perspective. It is when we begin to see history) than the structural account.

our lives as finite from some more infinite per-

spective that we feel despair. The meaningless- Concluding Perspectives

Downloaded from http://gerontologist.oxfordjournals.org/ at Monash University on December 6, 2014

ness of our lives in the face of death is the mean- We need to leave any structural stage claim

inglessness of the finite from the perspective of for Stage 7 ambiguous in the absence of both

the infinite. The resolution of the despair which empirical data and clear philosophic guidelines.

we call Stage 7 represents a continuation of the Its relevance for students of aging lies in the fact

process of taking a more cosmic perspective that two different approaches to stages, the

whose first phase is despair. It represents, in a Eriksonian and the structural, converge in sug-

sense, a shift from figure to ground. In despair gesting the possibility of an area of positive de-

we are the self seen from the distance of the velopment among the aging. A t the moment, we

cosmic or infinite. In the state of mind we meta- can only point to biographies and writings of the

phorically term Stage 7, we identify ourselves great for indications of this possibility. John

with the cosmic or infinite perspective, itself; we Dewey in his 70s wrote, Art and Experience, an

value life from its standpoint. analysis of contemplative experience. Around

Spinoza, a believer in principled ethics and the same time he wrote, A Common Faith. Both

in a science of natural laws, could still achieve suggest, if not movement to Stage 7, a qualita-

this state of mind, which he termed "the union tive broadening of vision beyond his earlier log-

of the mind with the whole of nature." Even ical, moral, and political concerns, conceptions,

most persons who are not "religious" temporarily and writings.

achieve this state of mind when on the moun- We do not know whether the sort of growth

taintop or before the ocean. A t such a time, Dewey showed in age was universal. The thing

what is ordinarily background becomes fore- that is most striking about aging is how some

ground, and the self is no longer figure to the aging people grow while others regress. In con-

ground. We sense the unity of the whole and trast to growth such as John Dewey's in some ag-

ourselves as part of that unity. This experience ing people, is the phenomena of regression in

of unity, often treated as a mere rush of mystic others. A pilot cross-sectional study of moral

feelings, is also associated with a structure of judgment in the aged (unpublished) suggested

conviction. The reversal of figure and ground that some, but far from all, aging people re-

felt in the contemplative moment has its analogy gressed to childish pre-conventional patterns of

in the development of belief. One may argue moral thought. Others, we might presume, were

that the crisis of despair, when thoroughly and growing in this period. The area of aging has

courageously explored, leads to a figure-ground the fascinating problem of sorting out the wisdom

shift which reveals the positive validity of the of age from all its counterfeits among the aging.

cosmic perspective implicit in the felt despair. The problem is rendered complex because if an

Such a claim is, of course, philosophically du- aging person has developed some wisdom we do

bious since the cognitive structure of this con- not have, it is hard for younger researchers to

viction are multiform. There is no single Stage detect it. If, however, some aging persons do

7 ontological-religious structure, no universal re- attain a greater wisdom, then among the most

ligion, as there is in some sense a single Stage 6 important things a student of aging could do is

structure of universal ethical principle. to clarify and communicate that wisdom to

Because of this, our notion of Stage 7 does others.

not quite fit the notion of a stage in the rigid Underlying the apparently arid formalism of

structural sense. The rigid structural model in- the Piaget-structural approach to stages is a

Winter 1973 501

warmer insight, the discovery that a child is a Handbook of socialization theory and research. Chi-

philosopher who constructs reality and its basic cago: McNally, 1969.

Kohlberg, L Notes toward stage 7. Unpublished lecture,

categories, space, time, causality, good, and evil. Harvard Univ., 1971.

Such an approach could hardly fail to find the Kohlberg, L Continuities in childhood and adult moral

aging are philosophers, at least insofar as they development revisited. In P. B. Baltes & K. W . Schaie

are developing. If this is the case, perhaps the (Eds.), Life-span developmental psychology: Personality

and socialization. New York: Academic Press, 1973.

field of aging could find some of its own most

Kohlberg, L, & Turiel, E. (Eds.), Recent research in moral

unique and deepest problems emerging from development. New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston,

philosophic concepts rather than from the more 1974. (in press)

usual concepts of biology and social science. Piaget, J . The general problem of the psychobiological

development of the child. In J . M. Tanner & B. In-

helder (Eds.), Discussion on child development. Vol. 4.

New York: International Universities Press, I960.

References

Rest, J . The hierarchical nature of moral judgment: Pat-

Fowler, J . Toward a theory of faith development. Un- terns of comprehension and preference of moral stages.

published paper, Harvard Univ. Divinity School, 1973. In L. Kohlberg & E. Turiel (Eds.), Recent research

Downloaded from http://gerontologist.oxfordjournals.org/ at Monash University on December 6, 2014

Kohlberg, L. Stage and sequence: The cognitive-develop- in moral development. New York: Holt, Rinehart &

mental approach to socialization. In D. A. Goslin (Ed.), Winston, 1974. (in press)

Models which postulate psychiatric disorders among the aging to be developmental products of

various antecedents in the life-histories of individuals are reviewed in comparison with alternate mod-

els of analysis on the one hand, and in relation to confirmatory evidence on the other. It is con-

cluded that such life-history oriented models constitute a popular but unsubstantiated point of view,

and that different analytic models may be suitable for explicating different kinds of conditions. A

developmental, contextual, and behavioral framework for analysis is proposed to guide the collection

of data, and to permit the discovery of those combinations of factors which result in the develop-

ment of differing psychiatric conditions. It is argued that availability of such data will facilitate the

test of the various models of pathogenesis proposed.

Life-History Antecedents in Psychiatric

Disorders of the Aging

Hugh B. Urban, PhD,1 and Daniel J. Lago, MA 2

A proposition commonly endorsed throughout it is now generally recognized that mental disturbances

such as involutional psychosis and senile dementia have

the geriatric literature holds that behavioral

their roots in childhood experiences.

disorders among the aging are significantly de-

termined by established premorbid patterns of Others such as Rockwell (1956) profess a gen-

behavior which have been laid down earlier in eral recognition of the continuity between a

the person's life. From this vantage point any person's "life-experiences" and the occurrence

effort to analyze and to explain the occurrence of behavioral disorders in late life. If such a

of such dysfunctional patterns among the aging proposition were to become substantiated and

would require an analysis in terms of the per- confirmed, it would be of significant import for

son's developmental background, an historical interventive programs of both a rehabilitative

approach which conceivably might have to be and preventive sort.

accomplished within a life-span frame. A num-

ber of writers state such a principle explicitly; Alternate Models of Analysis

Wolff (1970), for example, asserts that

Linear continuity models.The form in which

the general proposal has been made can be

1. Professor of Human Development & Psychology, Division of

Individual and Family Studies, College of Human Development, categorized into several different types. There

Pennsylvania State Univ., University Park 16802.

is first the possibility, as suggested by Roth-

2. Division of Individual & Family Studies, College of Human

Development, Pennsylvania State Univ., University Park 16802. schild (1956), that at least certain instances of

502 The Gerontologist

You might also like

- Elder, Curso de VidaDocument26 pagesElder, Curso de Vidavickypinilla839No ratings yet

- Positive Youth Development1Document92 pagesPositive Youth Development1MarcoNo ratings yet

- The Development of Self-Conceptions From Childhood To AdolescenceDocument7 pagesThe Development of Self-Conceptions From Childhood To AdolescenceTina DevianaNo ratings yet

- Adult Personality Development (2001)Document6 pagesAdult Personality Development (2001)Kesavan ManmathanNo ratings yet

- The Wiley-Blackwell Handbook of Infant Development, Volume 1: Basic ResearchFrom EverandThe Wiley-Blackwell Handbook of Infant Development, Volume 1: Basic ResearchNo ratings yet

- Martin Ruble Szkrybalo Gender DevelopmentDocument31 pagesMartin Ruble Szkrybalo Gender Developmentmeylingalvarado100% (1)

- The Ecology of Purposeful Living Across the Lifespan: Developmental, Educational, and Social PerspectivesFrom EverandThe Ecology of Purposeful Living Across the Lifespan: Developmental, Educational, and Social PerspectivesAnthony L. BurrowNo ratings yet

- OldthemesnewdirectionsDocument23 pagesOldthemesnewdirectionsvalkyrkiaNo ratings yet

- Developmental Plasticity: Behavioral and Biological Aspects of Variations in DevelopmentFrom EverandDevelopmental Plasticity: Behavioral and Biological Aspects of Variations in DevelopmentEugene GollinNo ratings yet

- Unesco - Eolss Sample Chapters: Developmental PsychologyDocument5 pagesUnesco - Eolss Sample Chapters: Developmental PsychologyArton BajgoraNo ratings yet

- Transitions and Transformations: Cultural Perspectives on Aging and the Life CourseFrom EverandTransitions and Transformations: Cultural Perspectives on Aging and the Life CourseNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Longitudinal Studies On Understanding Development From Young Adulthood To Old AgeDocument11 pagesThe Impact of Longitudinal Studies On Understanding Development From Young Adulthood To Old AgeLana PeharNo ratings yet

- Adolescent Development: Studying and Promoting Positive Youth DevelopmentDocument2 pagesAdolescent Development: Studying and Promoting Positive Youth DevelopmentRianNo ratings yet

- Determinants of Behavioral DevelopmentFrom EverandDeterminants of Behavioral DevelopmentF. J. MönksNo ratings yet

- 17 Adolescents' Social Development and The Role of ReligionDocument33 pages17 Adolescents' Social Development and The Role of ReligionYq WanNo ratings yet

- From Nerds To NormalsDocument21 pagesFrom Nerds To NormalsSpencer ClaiborneNo ratings yet

- Elder 1994 Time, Human Agency, and Social ChangeDocument13 pagesElder 1994 Time, Human Agency, and Social ChangeHernán RodríguezNo ratings yet

- Adolescent Future OrientationDocument26 pagesAdolescent Future OrientationLast ChildNo ratings yet

- Appraising the Human Developmental Sciences: Essays in Honor of Merrill-Palmer QuarterlyFrom EverandAppraising the Human Developmental Sciences: Essays in Honor of Merrill-Palmer QuarterlyNo ratings yet

- Identity Spirituality DevPsyDocument10 pagesIdentity Spirituality DevPsyGiovanni PaoloNo ratings yet

- Renewal: The Inclusion of Integralism and Moral Values into the Social SciencesFrom EverandRenewal: The Inclusion of Integralism and Moral Values into the Social SciencesColbert RhodesNo ratings yet

- Cognitive Theories of Early Gender DevelopmentDocument31 pagesCognitive Theories of Early Gender DevelopmentStroescu MadalinaNo ratings yet

- Psychological AgeDocument15 pagesPsychological AgeannavalensaNo ratings yet

- (Jean Piaget Symposium) Larry Nucci, Geoffrey B. Saxe, Elliot Turiel - Culture, Thought, and Development-Psychology Press (2000)Document293 pages(Jean Piaget Symposium) Larry Nucci, Geoffrey B. Saxe, Elliot Turiel - Culture, Thought, and Development-Psychology Press (2000)marcioandrei.infoNo ratings yet

- Social Cognition Social Neuroscience and Evolutionary Social PsychologyDocument19 pagesSocial Cognition Social Neuroscience and Evolutionary Social PsychologyPatricio González GardunoNo ratings yet

- A Conception of Adult DevelopmentDocument11 pagesA Conception of Adult DevelopmentJosue Claudio DantasNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Longitudinal Studies On Understanding Development From Young Adulthood To Old AgeDocument10 pagesThe Impact of Longitudinal Studies On Understanding Development From Young Adulthood To Old AgeVitor CostaNo ratings yet

- Seattle Longitudinal Study2010Document6 pagesSeattle Longitudinal Study2010pat patNo ratings yet

- Culture and Human DevelopmentDocument654 pagesCulture and Human DevelopmentSoham GuchaitNo ratings yet

- Adolescence Anthropological InquiryDocument267 pagesAdolescence Anthropological InquiryRachel CuratoNo ratings yet

- Arnett (2006)Document4 pagesArnett (2006)Wulil AlbabNo ratings yet

- Pag-Unawa Sa Sarili: Gawain: PanutoDocument7 pagesPag-Unawa Sa Sarili: Gawain: PanutoJaymar PastorNo ratings yet

- Forging the Male Spirit: The Spiritual Lives of American College MenFrom EverandForging the Male Spirit: The Spiritual Lives of American College MenNo ratings yet

- Understanding Human Social DevelopmentDocument18 pagesUnderstanding Human Social DevelopmentssNo ratings yet

- Democracy and Education - An Introduction to the Philosophy of EducationFrom EverandDemocracy and Education - An Introduction to the Philosophy of EducationNo ratings yet

- New Perspectives on Moral Change: Anthropologists and Philosophers Engage with Transformations of Life WorldsFrom EverandNew Perspectives on Moral Change: Anthropologists and Philosophers Engage with Transformations of Life WorldsCecilie EriksenNo ratings yet

- Havighurst1956 Research of Developmental Task ConceptDocument9 pagesHavighurst1956 Research of Developmental Task Conceptcandle.flame97No ratings yet

- "Entering Boys' World" Relational MasculinitiesDocument5 pages"Entering Boys' World" Relational Masculinitiescagedo5892No ratings yet

- Developmental Psychology Academic EssayDocument10 pagesDevelopmental Psychology Academic EssaybrainistheweaponNo ratings yet

- Developmental Tasks of Older People - Implications For Group WorkDocument73 pagesDevelopmental Tasks of Older People - Implications For Group WorkVinay SinghNo ratings yet

- Psychological Foundations of AttitudesFrom EverandPsychological Foundations of AttitudesRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Life-Span Development (Developmental Psychology) Seventeenth Edition John W. SantrockDocument28 pagesLife-Span Development (Developmental Psychology) Seventeenth Edition John W. SantrockKarylle Pingol100% (1)

- Janet Zollinger Giele (Ed.), Glen H. Elder (Ed.) - Methods of Life Course Research - Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches-SAGE Publications (1998)Document361 pagesJanet Zollinger Giele (Ed.), Glen H. Elder (Ed.) - Methods of Life Course Research - Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches-SAGE Publications (1998)Maria Júlia100% (1)

- Age IdentityDocument5 pagesAge IdentityhawwaNo ratings yet

- Spirituality As A Positive Youth Development ConstructDocument8 pagesSpirituality As A Positive Youth Development Constructiker1303No ratings yet

- Syllabus With Nos of Reporters CHild and Adolescent PsychologyDocument2 pagesSyllabus With Nos of Reporters CHild and Adolescent PsychologyZienna M. GualvezNo ratings yet

- Chapter KOPINGDocument29 pagesChapter KOPINGRofiqoh NoerNo ratings yet

- How Healthy Are We?: A National Study of Well-Being at MidlifeFrom EverandHow Healthy Are We?: A National Study of Well-Being at MidlifeNo ratings yet

- Life Span Perspective PaperDocument3 pagesLife Span Perspective PaperElbert WashingtonNo ratings yet

- Paren Child Relationship Practical L.N.B Write UpDocument49 pagesParen Child Relationship Practical L.N.B Write UpIndrashis MandalNo ratings yet

- The Importance of Ensuring Accurate and Appropriate Data CollectionDocument3 pagesThe Importance of Ensuring Accurate and Appropriate Data Collectioncris annNo ratings yet

- PsychopathologyDocument8 pagesPsychopathologySmerylGoldNo ratings yet

- EFA 219 Module 5 - Sociological Foundations of EducationDocument5 pagesEFA 219 Module 5 - Sociological Foundations of EducationGATTE EMILENo ratings yet

- LP Bus Ethics 2.1Document2 pagesLP Bus Ethics 2.1Aben Ger SimapanNo ratings yet

- Thompson Et Al. (2021) - Internet-Based Acceptance and Commitment TherapyDocument16 pagesThompson Et Al. (2021) - Internet-Based Acceptance and Commitment TherapyDaniel Garvi de Castro100% (1)

- Zsoka PDFDocument13 pagesZsoka PDFMasliana SahadNo ratings yet

- Graphic Organizers As Thinking TechnologyDocument32 pagesGraphic Organizers As Thinking TechnologyGab Ilagan100% (1)

- Lesson Plan FMTDocument5 pagesLesson Plan FMTElizendaNo ratings yet

- Mapeh 9 Tos 1ST QuarterDocument5 pagesMapeh 9 Tos 1ST QuarterKrizha Kate MontausNo ratings yet

- Sri Lanka Technical College MaradanaDocument4 pagesSri Lanka Technical College Maradanamophamed ashfaqueNo ratings yet

- Case AnalysisDocument24 pagesCase Analysisbhar4tpNo ratings yet

- Group 2-Constructivist Approach and Problem Solving ApproachDocument33 pagesGroup 2-Constructivist Approach and Problem Solving ApproachIman NulhakimNo ratings yet

- Personal Quality ChecklistDocument5 pagesPersonal Quality ChecklistUDAYAN SHAH100% (2)

- Study Habits InventoryDocument6 pagesStudy Habits InventoryDicky Arinta100% (1)

- BHNs PresentationDocument10 pagesBHNs PresentationHodan HaruriNo ratings yet

- PEC Self Rating Questionnaire and Score Computation 2Document10 pagesPEC Self Rating Questionnaire and Score Computation 2kenkoykoy0% (2)

- Subramaniam 2007Document10 pagesSubramaniam 2007Echo PurnomoNo ratings yet

- Review of The Related LiteratureDocument8 pagesReview of The Related LiteratureNethel Clarice D. Durana40% (5)

- Calm Course Outline Hodgson Fall 2014Document2 pagesCalm Course Outline Hodgson Fall 2014api-250760184No ratings yet

- Lesson 2 DREAM BELIEVE SURVIVEDocument14 pagesLesson 2 DREAM BELIEVE SURVIVEYasmin Pheebie BeltranNo ratings yet

- A. Ideational LearningDocument2 pagesA. Ideational LearningSherish Millen CadayNo ratings yet

- Problems Encountered Before, During and After The ExamDocument2 pagesProblems Encountered Before, During and After The ExamDivina Mercedes S. FernandoNo ratings yet

- Activity 3 - Samonte 2aDocument6 pagesActivity 3 - Samonte 2aSharina Mhyca SamonteNo ratings yet

- CommunicationDocument92 pagesCommunicationAnaida KhanNo ratings yet

- Byham DDI TargetedSelectionDocument22 pagesByham DDI TargetedSelectionJACOB ODUORNo ratings yet

- Core Values Reference ListDocument1 pageCore Values Reference Listt836549100% (1)

- Bipolar DisorderDocument29 pagesBipolar DisorderadeebmoonymoonNo ratings yet

- Fhs 1500 U4 Observation - EditedDocument2 pagesFhs 1500 U4 Observation - Editedapi-302132755No ratings yet

- Exercise Addiction A Literature ReviewDocument7 pagesExercise Addiction A Literature Reviewc5sq1b48100% (1)

- Interjection SDocument10 pagesInterjection SJose Gregorio VargasNo ratings yet