Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Fistula First Stent Second

Uploaded by

OccamsRazorCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Fistula First Stent Second

Uploaded by

OccamsRazorCopyright:

Available Formats

The n e w e ng l a n d j o u r na l of m e dic i n e

5. Liese AD, DAgostino RB Jr, Hamman RF, et al. The burden of cardiovascular disease risk factors according to body mass index

diabetes mellitus among US youth: prevalence estimates from the in US adults. JAMA 2005;293:1868-74.

SEARCH for Diabetes in Youth Study. Pediatrics 2006;118:1510-8. 11. Lipscombe LL, Hux JE. Trends in diabetes prevalence, inci-

6. Franks PW, Hanson RL, Knowler WC, Sievers ML, Bennett dence, and mortality in Ontario, Canada 1995-2005: a popula-

PH, Looker HC. Childhood obesity, other cardiovascular risk tion-based study. Lancet 2007;369:750-6.

factors, and premature death. N Engl J Med 2010;362:485-93. 12. Gerstein HC, Santaguida P, Raina P, et al. Annual incidence

7. Li C, Ford ES, Zhao G, Mokdad AH. Prevalence of pre-diabe- and relative risk of diabetes in people with various categories of

tes and its association with clustering of cardiometabolic risk dysglycemia: a systematic overview and meta-analysis of pro-

factors and hyperinsulinemia among U.S. adolescents: National spective studies. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2007;78:305-12.

Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2005-2006. Diabetes 13. Hirst K, Baranowski T, DeBar L, et al. HEALTHY study ra-

Care 2009;32:342-7. tionale, design and methods: moderating risk of type 2 diabetes

8. Morrison JA, Glueck CJ, Horn PS, Wang P. Childhood predic- in multi-ethnic middle school students. Int J Obes (Lond)

tors of adult type 2 diabetes at 9- and 26-year follow-ups. Arch 2009;33:Suppl 4:S4-S20.

Pediatr Adolesc Med 2010;164:53-60. 14. Murray CJ, Kulkarni SC, Michaud C, et al. Eight Americas:

9. Minino AM, Arias E, Kochanek KD, Murphy SL, Smith BL. investigating mortality disparities across races, counties, and

Deaths: final data for 2000. Natl Vital Stat Rep 2002;50:1-119. race-counties in the United States. PLoS Med 2006;3(9):e260.

10. Gregg EW, Cheng YJ, Cadwell BL, et al. Secular trends in Copyright 2010 Massachusetts Medical Society.

Fistula First, Stent Graft Second

Robert K. Kerlan, Jr., M.D., and Jeanne M. LaBerge, M.D.

A growing number of patients in the United States The major cause of failure of prosthetic arterio-

undergo efficient hemodialysis through autoge- venous grafts is stenosis at the venous anastomo-

nous arteriovenous fistulas or prosthetic arterio- sis of the graft. Attempts to prevent or reduce the

venous grafts. Unfortunately, these vascular con- incidence of this problem through surgical or

duits are fraught with complications, and failing pharmacologic means have been largely unpro-

access remains the leading cause of hospitaliza- ductive. In a recent report in the Journal, pharma-

tion for patients undergoing dialysis.1 cologic treatment with dipyridamole and aspirin

The superiority of autogenous arteriovenous resulted in only a small (5-percentage-point) dif-

fistulas as compared with prosthetic arteriovenous ference in restenosis as compared with placebo.4

grafts is well established. Fistulas have a far Balloon angioplasty has been the standard

lower risk of failure and a reduced requirement treatment for stenosis of a venous anastomotic

for revision as compared with prosthetic grafts. graft. Yet the benefit of angioplasty is offset by

In 1997, the National Kidney Foundation Kidney a high rate of restenosis within weeks or a few

Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative recommended months after the procedure. To date, randomized,

a goal of arteriovenous fistula formation in 50% controlled trials have not shown a substantial pro-

of all new patients undergoing hemodialysis. In longation of graft patency after angioplasty, find-

2005, the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Ser- ings that have led to controversy regarding the

vices raised the target to 66% in the breakthrough merit of surveillance and early intervention.5

initiative that has become known as Fistula A variety of innovative percutaneous techniques

First.2 have been used to treat anastomotic graft stenos-

Unfortunately, a substantial number of patients es, such as cutting balloons, cryoballoons, and

lack suitable veins for the creation of autogenous bare-metal stents. None of these interventions

fistulas and require placement of prosthetic grafts. have significantly prolonged graft patency as com-

The high rate of graft failure in such patients pared with conventional balloon angioplasty in

leads to increased cost of treatment and periodic appropriately sized, prospective, randomized, con-

loss of access. Ameliorating the problem of graft trolled trials.6,7

stenosis has been the subject of intense investi- The study by Haskal et al. appears to be the

gation over the past decade. The study by Haskal first large, randomized, controlled trial to clearly

and colleagues in this issue of the Journal3 provides demonstrate superiority of an approach over bal-

hope that, as we enter the new decade, patients loon angioplasty. Their data reveal that treating

with arteriovenous grafts may experience a bright- a venous outflow stenosis with a stent graft more

er future. than doubles the rate of graft patency, and sub-

550 n engl j med 362;6 nejm.org february 11, 2010

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from nejm.org at the Bodleian Libraries of the University of Oxford on January 5, 2017. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright 2010 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

editorials

stantially reduces the need for reintervention, as of the Fistula First initiative, we are coming

compared with angioplasty. Although patients closer to realizing this goal. The most pressing

who presented with graft occlusion were not en- problems in the coming decade will lie not in

rolled in the study, it is logical to infer that stent managing arteriovenous graft failure but in pre-

grafts would have a similar patency advantage venting, detecting, and treating arteriovenous-fis-

when a venous outflow stenosis is identified after tula dysfunction.

removal of the thrombus. One hopes that the beneficial effects of stent

Despite the improved outcomes demonstrated grafts reported by Haskal et al. will also be

by Haskal et al., stent grafts do not represent a observed in patients with autogenous-fistula

panacea for patients with failing arteriovenous stenoses. Preliminary data are promising and sug-

grafts. Six months after stent-graft placement, pri- gest an advantage of stent grafts over angioplasty

mary dialysis-access patency was achieved in only or bare-metal stents.9 Perhaps more importantly,

half the patients. A pessimist might conclude that there is hope that stent grafts can be used to treat

performance of the arteriovenous graft can be im- central venous stenosis effectively. Balloon angio-

proved from dismal (with angioplasty) to merely plasty and bare-metal stents have yielded extreme-

poor (with stent grafts). Indeed, both angioplasty ly disappointing results in this anatomical loca-

and stent grafts are imperfect treatments, and tion, with incidences of primary patency at 1 year

even with this new technological innovation, there of 29% and 21%, respectively.10 A durable solution

is much room for improvement. to the problem of central venous stenosis would be

Several other details in the study by Haskal an extraordinary advance in the care of patients

et al. may temper enthusiasm for the immediate undergoing dialysis.

adoption of stent grafts as the treatment of choice In conclusion, the use of stent grafts to treat

for anastomotic arteriovenous graft stenosis. First, dysfunctional arteriovenous grafts is an important

there was a trend toward a higher rate of throm- advance that will most likely change the practice

botic occlusion in the stent-graft group (33%) than of percutaneous intervention and provide imme-

in the balloon-angioplasty group (21%) (P=0.10). diate benefit to the many patients suffering from

This raises the possibility that adjunctive system- graft dysfunction. If the findings of Haskal et al.

ic anticoagulant or antiplatelet therapy may yield are confirmed, the strategy for dialysis-access

additional benefit. A study of a stent graft bonded planning in the coming decade may change from

with heparin is currently under investigation.8 Fistula First to fistula first, arteriovenous graft

Second, the relatively short follow-up period in with stent-graft revision second.

the study by Haskal et al. limits our understand- Financial and other disclosures provided by the authors are

ing of the true clinical value of stent-graft revi- available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org.

sion in arteriovenous grafts. Though patency was From the University of California, San Francisco, San Francisco.

improved at 6 months, the longer-term outcomes 1. United States Renal Data System. USRDS 2009 annual data

are unknown. In the current health care environ- report: atlas of end-stage renal disease in the United States.

ment, the financial effect of stent-graft therapy Bethesda, MD: National Institute of Health, National Institute of

Diabetes and Digestive Diseases, 2009. (Accessed January 21, 2010,

must be considered. Will sufficient improvement at http://www.usrds.org/2009/slides/indiv/INDEX_ESRD.HTML.)

in arteriovenous graft patency at 2 to 3 years be 2. Vascular Access Work Group. Clinical practice guidelines for

observed, and will it offset the increased cost of vascular access. Am J Kidney Dis 2006;48:Suppl 1:S248-S273.

3. Haskal ZJ, Trerotola S, Dolmatch B, et al. Stent graft versus

stent-graft placement? balloon angioplasty for failing dialysis-access grafts. N Engl J

Finally, the study was powered to show non- Med 2010;362:494-503.

inferiority, and the sample size was relatively small 4. Dixon BS, Beck GJ, Vazquez MA, et al. Effect of dipyridamole

plus aspirin on hemodialysis graft patency. N Engl J Med 2009;

(190 patients). Although this clinical trial was well 360:2191-201.

designed, with careful assessment of venographic 5. White JJ, Bander SJ, Schwab SJ, et al. Is percutaneous trans-

and clinical end points, it will be important to luminal angioplasty an effective intervention for arteriovenous

graft stenosis? Semin Dial 2005;18:190-202.

confirm the study findings in subsequent inves- 6. Vesely TM, Siegel JB. Use of the peripheral cutting balloon to

tigations. treat hemodialysis-related stenoses. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2005;

The ultimate goal in hemodialysis management 16:1593-603.

7. Clark TW. Nitinol stents in hemodialysis access. J Vasc Interv

is to provide each patient with a vascular access Radiol 2004;15:1037-40.

that will last a lifetime. With widespread adoption 8. ClinicalTrials.gov. GORE VIABAHN Endoprosthesis Versus

n engl j med 362;6 nejm.org february 11, 2010 551

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from nejm.org at the Bodleian Libraries of the University of Oxford on January 5, 2017. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright 2010 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

editorials

Percutaneous Transluminal Angioplasty (PTA) to Revise AV Grafts hemodialysis: a prospective randomized clinical trial. J Vasc Surg

in Hemodialysis (REVISE) study. (ClinicalTrials.gov number, 2008;48:1524-31.

NCT00737672.) (Accessed January 21, 2010, at http://clinicaltrials 10. Bakken AM, Protack CD, Saad WE, Lee DE, Waldman DL,

.gov/ct2/show/NCT00737672.) Davies MG. Long-term outcomes of primary angioplasty and

9. Shemesh D, Goldin I, Zaghal I, Berlowitz D, Raveh D, Olsha primary stenting of central venous stenosis in hemodialysis pa-

D. Angioplasty with stent graft versus bare stent for recurrent tients. J Vasc Surg 2007;45:776-83.

cephalic arch stenosis in autogenous arteriovenous access for Copyright 2010 Massachusetts Medical Society.

552 n engl j med 362;6 nejm.org february 11, 2010

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from nejm.org at the Bodleian Libraries of the University of Oxford on January 5, 2017. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright 2010 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

You might also like

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Your Facial Expression and Body Languae: RED FLAGS and Safety NetDocument1 pageYour Facial Expression and Body Languae: RED FLAGS and Safety NetOccamsRazorNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Neonatology and Puerperium HYDocument6 pagesNeonatology and Puerperium HYOccamsRazorNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Obgyn OsceDocument1 pageObgyn OsceOccamsRazorNo ratings yet

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- OB (Antenatal) Exam: Comfortable. Couch Should Be A Comfortable Level For You TooDocument4 pagesOB (Antenatal) Exam: Comfortable. Couch Should Be A Comfortable Level For You TooOccamsRazor100% (1)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- GYN History OSCEDocument7 pagesGYN History OSCEOccamsRazorNo ratings yet

- General Considerations For Topical PreparationsDocument6 pagesGeneral Considerations For Topical PreparationsOccamsRazorNo ratings yet

- Gynaecology: Gum, Fertility, Contraception, and UrogynaecologyDocument46 pagesGynaecology: Gum, Fertility, Contraception, and UrogynaecologyOccamsRazorNo ratings yet

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- AntibioticsDocument6 pagesAntibioticsOccamsRazor100% (1)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- History From A Collateral EtcDocument1 pageHistory From A Collateral EtcOccamsRazorNo ratings yet

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Patient With Breathing Difficulties: AssessmentDocument5 pagesThe Patient With Breathing Difficulties: AssessmentOccamsRazorNo ratings yet

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Transcription Sample Old Essay PDFDocument7 pagesTranscription Sample Old Essay PDFOccamsRazorNo ratings yet

- Public Health OSCEDocument5 pagesPublic Health OSCEOccamsRazor100% (1)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- TJC Chemistry H2 Y1 2009Document21 pagesTJC Chemistry H2 Y1 2009OccamsRazor100% (1)

- Higher 3 Concept TestDocument6 pagesHigher 3 Concept TestOccamsRazorNo ratings yet

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Derm Quiz: True/falseDocument7 pagesDerm Quiz: True/falseOccamsRazorNo ratings yet

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Derma PDFDocument20 pagesDerma PDFShivBalakChauhan0% (1)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Higher 3 Pharmaceutical Chemistry Concept Test 3Document9 pagesHigher 3 Pharmaceutical Chemistry Concept Test 3OccamsRazorNo ratings yet

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- 2006 JC 1 H2 JCT & Promo - Differential EquationsDocument3 pages2006 JC 1 H2 JCT & Promo - Differential EquationsOccamsRazorNo ratings yet

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Vitalsigns 180617200506Document34 pagesVitalsigns 180617200506Maricris Tac-an Calising-PallarNo ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Vascular SurgeryDocument458 pagesVascular SurgeryZoltan KardosNo ratings yet

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Basic EKG 2: Dr. Wattana Wongtheptien M.D. Cardiologist Chiangrai Regional HospitalDocument79 pagesBasic EKG 2: Dr. Wattana Wongtheptien M.D. Cardiologist Chiangrai Regional HospitalVeerapong Vattanavanit0% (1)

- Atlas ECG PPT2Document121 pagesAtlas ECG PPT2moldovanka88_6023271100% (1)

- Pediatric Advanced Life Support Provider Manual: January 2012Document1 pagePediatric Advanced Life Support Provider Manual: January 2012Danhil RamosNo ratings yet

- Arterial Line and Central LineDocument32 pagesArterial Line and Central LineOrachorn AimarreeratNo ratings yet

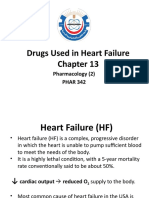

- Drugs Used in Heart Failure: Pharmacology (2) PHAR 342Document19 pagesDrugs Used in Heart Failure: Pharmacology (2) PHAR 342Dana HamarshehNo ratings yet

- Facial Vascular Danger Zones For Filler Injections: Uwe Wollina - Alberto GoldmanDocument8 pagesFacial Vascular Danger Zones For Filler Injections: Uwe Wollina - Alberto GoldmanLuis Fernando WeffortNo ratings yet

- Iv AdministrationDocument3 pagesIv AdministrationHNo ratings yet

- Atls & AclsDocument49 pagesAtls & AclsSanjay SathasevanNo ratings yet

- Cor PulmonaleDocument27 pagesCor PulmonaleumapathisivanNo ratings yet

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Heart Specialist in Haldwani - Google SearchDocument1 pageHeart Specialist in Haldwani - Google SearchManoj UpadhyayNo ratings yet

- Cerebral AutoregulationDocument5 pagesCerebral AutoregulationJana ThukuNo ratings yet

- Risk Factors For HypertensionDocument3 pagesRisk Factors For Hypertensiontan junhaoNo ratings yet

- Entresto Marketing PlanDocument1 pageEntresto Marketing PlanSalmanAhmedNo ratings yet

- NCP For Dizziness and HeadacheDocument4 pagesNCP For Dizziness and HeadacheDharyl Joshua67% (12)

- Clinical and Angiographic Profile of Coronary Artery Disease in Young Women - A Tertiary Care Centre Study From North Eastern IndiaDocument13 pagesClinical and Angiographic Profile of Coronary Artery Disease in Young Women - A Tertiary Care Centre Study From North Eastern IndiaIJAR JOURNALNo ratings yet

- Implanted Cardioverter Defibrillator (Icd) Identification - : Wallet CardDocument1 pageImplanted Cardioverter Defibrillator (Icd) Identification - : Wallet CardΑλεξης ΝεοφυτουNo ratings yet

- Cardiovasular SystemDocument5 pagesCardiovasular SystemAsher Eby VargeeseNo ratings yet

- 20 Questions HypothermiaDocument8 pages20 Questions HypothermiaManuelNo ratings yet

- Intepretasi EKG (DR Eka)Document93 pagesIntepretasi EKG (DR Eka)Danil Anugrah JayaNo ratings yet

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Hipertension Arterial (Hta) : ¿Qué Es La Hipertensión Arterial Según La Organización Mundial de La Salud (OMS) ?Document4 pagesHipertension Arterial (Hta) : ¿Qué Es La Hipertensión Arterial Según La Organización Mundial de La Salud (OMS) ?CésarÑañezNo ratings yet

- NSG 461 - Disease Deep DiveDocument5 pagesNSG 461 - Disease Deep Diveapi-641353289100% (1)

- Blood Sugar Blood Pressure Log 12012017Document2 pagesBlood Sugar Blood Pressure Log 12012017Mahbub RahmanNo ratings yet

- Phleb NotesDocument122 pagesPhleb NotesJan Melvich FernandezNo ratings yet

- Congenital Heart Surgery: The Appropriate Diagnosis Is Achieved byDocument9 pagesCongenital Heart Surgery: The Appropriate Diagnosis Is Achieved byprofarmahNo ratings yet

- 12 Lead EKG 101Document84 pages12 Lead EKG 101zul fatmah100% (1)

- Varicose VeinsDocument2 pagesVaricose VeinsroycNo ratings yet

- Small Animal/ExoticsDocument3 pagesSmall Animal/Exoticstaner_soysurenNo ratings yet

- Case Presentation 2Document27 pagesCase Presentation 2Sathish SPNo ratings yet

- Love Life: How to Raise Your Standards, Find Your Person, and Live Happily (No Matter What)From EverandLove Life: How to Raise Your Standards, Find Your Person, and Live Happily (No Matter What)Rating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- LIT: Life Ignition Tools: Use Nature's Playbook to Energize Your Brain, Spark Ideas, and Ignite ActionFrom EverandLIT: Life Ignition Tools: Use Nature's Playbook to Energize Your Brain, Spark Ideas, and Ignite ActionRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (404)