Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Phys Ther 2009 Rundell 82 90

Uploaded by

Lynn JC GranadosCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Phys Ther 2009 Rundell 82 90

Uploaded by

Lynn JC GranadosCopyright:

Available Formats

Physical Therapist Management of Acute and

Chronic Low Back Pain Using the World Health

Organization's International Classification of

Functioning, Disability and Health

Sean D Rundell, Todd E Davenport and Tracey Wagner

PHYS THER. 2009; 89:82-90.

Originally published online November 13, 2008

doi: 10.2522/ptj.20080113

The online version of this article, along with updated information and services, can be

found online at: http://ptjournal.apta.org/content/89/1/82

Online-Only Material http://ptjournal.apta.org/content/suppl/2009/01/27/89.1.82

.DC1.html

Collections This article, along with others on similar topics, appears

in the following collection(s):

Case Reports

Disability Models

Injuries and Conditions: Low Back

International Classification of Functioning, Disability

and Health (ICF)

e-Letters 2 e-letter(s) have been posted to this article, which can

be accessed for free at:

http://ptjournal.apta.org/cgi/eletters/89/1/82

To submit an e-Letter on this article, click here or click on

"Submit a response" in the right-hand menu under

"Responses" in the online version of this article.

E-mail alerts Sign up here to receive free e-mail alerts

Correction A correction has been published for this article. The

correction has been appended to this PDF. The

correction is also available online at:

http://ptjournal.apta.org/content/89/3/310.full.pdf

Downloaded from http://ptjournal.apta.org/ by guest on January 22, 2015

Case Report

Physical Therapist Management of

Acute and Chronic Low Back Pain

Using the World Health

Organizations International

Classification of Functioning,

Disability and Health

Sean D Rundell, Todd E Davenport, Tracey Wagner

SD Rundell, PT, DPT, OCS, is Phys-

ical Therapist, Portland Sports

Medicine and Spine Physical Ther-

Background and Purpose. The World Health Organizations Classification of

apy, 1610 SE Glenwood St, Port- Functioning, Disability and Health (WHO-ICF) model was developed to describe,

land, OR 97202 (USA). Address all classify, and measure function in health care practice and research. Recently, this

correspondence to Dr Rundell at: model has been promoted as a successor to the Nagi model by some authors in the

sean@pdxspine.com. physical therapy literature. However, conceptual work in demonstrating use of the

TE Davenport, PT, DPT, OCS, is WHO-ICF model in physical therapist management of individual patients remains

Assistant Professor, Department of sparse. The purpose of this case report series is to demonstrate the application of the

Physical Therapy, Thomas J. Long WHO-ICF model in clinical reasoning and physical therapist management of acute and

School of Pharmacy and Health

chronic low back pain.

Sciences, University of the Pacific,

Stockton, California, and Clinical

Specialist, Department of Physical Case Description. Two patients, 1 with acute low back pain and 1 with chronic

Medicine and Rehabilitation, Kai- low back pain, were treated pragmatically using the WHO-ICF model and other

ser Permanente Woodland Hills applicable models of clinical reasoning.

Medical Center, Woodland Hills,

California.

Intervention. Manual therapy, exercise, and education interventions were di-

T Wagner, PT, MPT, OCS, is Clin- rected toward relevant body structure and function impairments, activity limitations,

ical Specialist, Department of

and contextual factors based on their hypothesized contribution to functioning and

Physical Medicine and Rehabilita-

tion, Kaiser Permanente Wood- disability.

land Hills Medical Center, and

Clinical Mentor, Residency in Or- Outcome. Both patients demonstrated clinically significant improvements in mea-

thopaedic Physical Therapy, Kaiser sures of pain, disability, and psychosocial factors after 3 weeks and 10 weeks of

Permanente Southern California. intervention, respectively.

[Rundell SD, Davenport TE, Wag-

ner T. Physical therapist manage- Discussion. The WHO-ICF model appears to provide an effective framework for

ment of acute and chronic low physical therapists to better understand each persons experience with his or her

back pain using the World Health

disablement and assists in prioritizing treatment selection. The explicit acknowledg-

Organizations International Classi-

fication of Functioning, Disability ment of personal and environmental factors aids in addressing potential barriers. The

and Health. Phys Ther. 2009;89: WHO-ICF model integrates well with other models of practice such as Sacketts

8290.] principles of evidence-based practice, the rehabilitation cycle, and Edwards and

2009 American Physical Therapy colleagues clinical reasoning model. Future research should examine out-

Association comes associated with the use of the WHO-ICF model using adequately designed

clinical trials.

Post a Rapid Response or

find The Bottom Line:

www.ptjournal.org

82 f Physical Therapy Volume 89 Number 1 January 2009

Downloaded from http://ptjournal.apta.org/ by guest on January 22, 2015

Low Back Pain and the WHO-ICF Model

L

ow back pain (LBP) is among the

most ubiquitous and expensive

health conditions affecting the

developed world.1 4 Low back pain

also is among the most common

musculoskeletal conditions treated

by physical therapists.5 As a complex

biopsychosocial phenomenon, the

application of the medical model to

describe LBP has challenged the

identification of optimal treatments.

Disability models provide useful

patient-centered schema that assist

clinicians in understanding the influ-

ences and relationships among LBP,

its hypothetical contributing factors,

and its resultant disability. Disable-

ment models such as the Nagi model

can help a clinician evaluate and pri-

oritize the components that may be

most responsive to interventions to

reduce disability,6,7 and they can be

helpful in determining needs, match-

ing interventions to health states,

and evaluating outcomes.8,9

The World Health Organizations In- Figure 1.

World Health Organizations International Classification of Functioning, Disability and

ternational Classification of Func- Health model.

tioning, Disability and Health

(WHO-ICF) model was developed to

simplify the process of describing,

classifying, and measuring function WHO-ICF model includes a classifica- the Nagi model. The WHO-ICF model

and health. It provides a method tion system to further describe envi- already has been applied to describe

that considers biological, individual, ronmental and personal contextual certain chronic conditions, such as

and social contributions that can be factors that can influence function- LBP, in order to derive core sets

used across clinical practice and re- ing and disability.10 and brief core sets that use con-

search. The WHO-ICF model has 2 sistent language.8,13 However, the

main components (Fig. 1). The first The WHO-ICF model is thought to WHO-ICF models usefulness to clin-

part is functioning and disability, retain certain advantages over the ical reasoning in individual patient

which is further divided into body Nagi model. First, the WHO-ICF cases remains unclear. The purpose

functions and structures, activities, model explicitly acknowledges bi- of this case report series is to dem-

and participation. Body functions directional relationships among do- onstrate the use of the WHO-ICF

and structures are assessed in terms mains of function and contextual framework in the management of

of change in physiological function factors. In addition, the WHO-ICF acute and chronic LBP.

and anatomical structure. Activity is models description of contextual

the execution of a task or action, factors would appear to reinforce Patient 1 (Chronic LBP)

and participation is defined as in- physical therapists consideration of History

volvement in life affairs. Function- patients affective, social, and envi- The patient was a 53-year-old woman

ing is the positive aspect of these ronmental factors that contribute to with a chief concern of a 28-year

components, and disability is the the physical therapists prognosis. history of LBP. She reported an insid-

negative aspect. Each component These advantages have contributed ious onset of symptoms that had pro-

can be broken down into categories to the WHO-ICF model being advo- gressively worsened and had be-

relating to functioning and disability. cated in the physical therapy litera- come constant during the last 3

The second main component of the ture11,12 as a potential successor to years. Pain intensity, as measured

January 2009 Volume 89 Number 1 Physical Therapy f 83

Downloaded from http://ptjournal.apta.org/ by guest on January 22, 2015

Low Back Pain and the WHO-ICF Model

with a numeric pain rating scale,14 16 pressive symptoms; and her Fear- ual muscle tests of the hip revealed

was 5/10 at intake, 10/10 at worst, Avoidance Belief Questionnaire bilateral gluteus medius muscle

and 3/10 at best. Lifting, bending for- (FABQ)21,22 work subscale score strength (force-generating capacity)

ward, and sitting for 15 to 20 min- was 2/42, suggesting minimal fear- was 3/5 and gluteus maximus mus-

utes aggravated symptoms. The pa- avoidance behavior concerning work cle strength was 3/5.27 Abdominal

tient described the symptoms as activities. However, her FABQ physi- performance testing, which was con-

variable from day to day, but typi- cal activity subscale score was 20/24, ducted as described by Sahrmann,28

cally worse at the end of the day. She indicating high fear-avoidance behav- showed level 0.3 was the highest

estimated her sleep was interrupted ior concerning physical activity out- level performed correctly, where

by 50% because of her LBP. Symp- side of work. The Lower Back Activ- level 2 indicates adequate strength

toms eased with heat, massage, and ity Confidence Scale (LoBACS)23,24 and control. Hypomobility and re-

over-the-counter ibuprofen. Associ- revealed scores of 49%, 90%, and production of greater left-sided pain

ated symptoms included an intermit- 100% for the perceived ability to than right-sided pain were noted

tent ache along the paraspinal mus- function in activities of daily living with posterior-anterior pressures at

culature and an intermittent ache and work activities, self-regulate L4-L5 and L5-S1.29,30

to throbbing pain radiating from the symptoms, and perform therapeutic

lateral hips to the anterior thighs. exercises, respectively. Evaluation

She also reported occasional bilateral Based on the initial examination

numbness of the entire foot at night The patient was observed to have data, the mediators influencing the

and upon waking. The patient re- decreased lumbar lordosis, posterior patients chronic LBP were catego-

ported having no saddle paresthesia, pelvic tilt, and forward head in a rized using the WHO-ICF model

change in bowel and bladder func- standing position. Decreased hip ex- (Tab. 1). We hypothesized that hip

tion, or generalized weakness or tension during terminal stance bilat- muscle performance and length im-

incoordination of her lower erally and increased frontal-plane pairments observed resulted in poor

extremities. motion of the pelvis during mid- segmental stabilization and conse-

stance were noted during observa- quent LBP, causing limitations in the

Other medical history included an tional gait assessment. Patellar re- activities of lifting and carrying and

appendectomy, tonsillectomy, hys- flexes were 1 bilaterally, and maintaining body positions. Difficul-

terectomy, hypertension, hypercho- Achilles reflexes could not be elic- ties with these activities were hy-

lesterolemia, and depression. Her ited. Myotomal and dermatomal pothesized to negatively affect her

depressive symptoms were being function were normal. Standing lum- participation in employment duties

treated with bupropion hydrochlo- bar active range of motion (AROM)25 and leisure activities. They also were

ride (150 mg twice daily). Other cur- revealed increased left-sided pain thought to be involved in a cycle that

rent medications included lisinopril with flexion but normal excursion. promoted further impaired muscle

(10 mg once daily) and hydrochlo- Extension, right side bending, and power functions and reduced joint

rothiazide (25 mg once daily) for hy- left side bending did not reproduce mobility.

pertension, metoclopramide (10 mg symptoms, although excursion was

once daily) for gastroesophageal re- decreased. Passive range of motion Another important hypothesized bi-

flux, and lamotrigine (200 mg once (PROM) during a right straight leg directional relationship was between

daily) for stabilizing mood. The pa- raise (SLR), as measured with bubble the personal factor of her high FABQ

tients work activities included lift- inclinometry, was 52 degrees, with physical activity score and her activ-

ing and carrying boxes of files and reproduction of right gluteal pain, ity limitations. We hypothesized that

sitting at a computer. Her hobbies but sensitizing using dorsiflexion fear-avoidance beliefs acted as a po-

included gardening. The patients was negative. Left SLR was positive tential barrier to her physical activi-

goals were to garden and perform all at 60 degrees for familiar back pain, ties. Conversely, we thought that the

work duties with a pain level of and sensitizing with dorsiflexion was pain experienced during these activ-

4/10. positive. ities reinforced her avoidance beliefs

concerning them. The personal fac-

Examination Hip extension PROM during a tor of low self-efficacy concerning

At intake, the patients Oswestry Thomas test, as measured using bub- daily living and work activities was

Low Back Disability Questionnaire ble inclinometry with the knee thought to be another factor contrib-

(ODQ)15,17,18 score was 18/50, her flexed,26 revealed right hip exten- uting to her activity limitations. Go-

Beck Depression Index (BDI)19,20 sion lacking 15 degrees and left hip ing in the other direction, the pain

was 8/63, indicating minimal de- extension lacking 18 degrees. Man- and limitation with physical activi-

84 f Physical Therapy Volume 89 Number 1 January 2009

Downloaded from http://ptjournal.apta.org/ by guest on January 22, 2015

Low Back Pain and the WHO-ICF Model

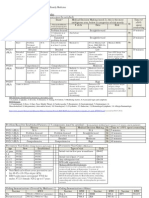

Table 1.

The World Health Organizations International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (WHO-ICF) Model Applied to the

Evaluation of Patient 1 (Chronic Low Back Pain)a

Body Structures and Functions Activities Participation

Patients perspective Pain in back and thighs Lifting Unable to garden

Foot numbness Bending Decreased work tolerance

Sitting 20 min Interrupted sleep

Physical therapists perspective 1. Reduced muscle power functions 1. Lifting and carrying objects 1. Remunerative employment

(b730) (d430) (d850)

2. Reduced mobility of joint functions 2. Maintaining body position (d410) 2. Recreation and leisure (d920)

(b710)

3. Gait pattern function (b770)

Contextual Factors

Personal

Temperament and personality functions: fear-avoidance behavior for physical activities and perceived ability to function in activities of daily living

and work activities

Environmental

Design construction and buildings products and technology of buildings for private use (e155)

Products and technology for employment (e135)

Labor and employment services, systems, and policies (e590)

a

The physical therapists perspective includes the ranked WHO-ICF categories within each of the components. Hip muscle performance and length deficits

were ranked as the primary body structures and functions to be treated because of their degree of impairment found during the examination. They were

hypothesized to result in poor spinal segmental stabilization and consequent low back pain, which principally contributed to the patients activity limitations

of lifting and carrying and maintaining body positions and her participation restrictions in employment and leisure. The personal contextual factor of fear of

physical activity was addressed as a secondary factor that also contributed to activity limitations and participation restrictions.

ties likely reduced her perceived ple days. To address decreased ab- increased pain. She regularly sat at

ability to perform them. Her work dominal muscle power function, she work for 30 minutes without pain.

environment, involving low shelves was instructed in supine abdominal Her worst pain was reported as 3/10.

and filing cabinets, and the distance drawing-in.28 Quarter squats without Her ODQ score was 6/50. Hip flex-

required to transport files were envi- allowing knee valgus were pre- ion with the Thomas test was 6 de-

ronmental factors that may have neg- scribed for muscle performance im- grees on the left and 10 degrees on

atively influenced her participation pairments of her hip lateral rotators the right. Abdominal strength was

in work duties. and abductors, and a hip flexor graded as level 0.4.28 The patient

stretch was prescribed to address canceled a follow-up appointment at

Intervention her impairment of hip extension. On 14 weeks and subsequently was con-

The patient was educated on her follow-up visits, interventions fo- tacted by telephone. Final question-

physical therapists diagnosis, prog- cused on contract-relax procedures naires revealed an ODQ score of

nosis, and plan of care. She was seen to the rectus femoris and iliopsoas 2/50, a BDI of 4/63, an FABQ work

for 4 visits over 10 weeks. Patient muscles. Abdominal bracing in a su- subscale score of 0/42, and an FABQ

education and graded exercise were pine position was progressed in in- physical activity subscale score of

used to address her avoidance of tensity to bracing with alternate 6/24. The patients LoBACS scores

physical activity. Specifically, she marching.28 Prone hip extension were 87%, 100%, and 100% for the

was educated during the initial visit AROM with knee flexion was added functional, self-regulatory, and exer-

that pain did not signal harm, to to strengthen the hip extensors, and cise subscales, respectively. Pain in-

maintain a consistent activity pace, squatting was progressed in depth tensity, as measured with a numeric

and to stay as active as tolerable. This and resistance provided. pain rating scale, was 2/10 at worst.

was reinforced during discussions in The patient global rating of change

subsequent visits. Graded exercise Outcome scale31 revealed a perception of

consisted of beginning a daily pro- At 10 weeks, the patient reported much improved.

gram of walking for 15 minutes and that she was able to bend and carry

progressing the duration every cou- charts at work for a full day without

January 2009 Volume 89 Number 1 Physical Therapy f 85

Downloaded from http://ptjournal.apta.org/ by guest on January 22, 2015

Low Back Pain and the WHO-ICF Model

Patient 2 (Acute LBP) times daily) for depressive symp- Achilles tendon deep tendon reflex

History toms, methylprednisolone (4 mg tests were 2 bilaterally. Lumbar

The patient was a 38-year-old female once daily) for inflammation, fexofe- AROM revealed flexion was normal

computer programmer. Her chief nadine (60 mg once daily) for aller- and status quo. Extension was lim-

concern was a 14-day history of in- gies, and norethindrone (35 mg once ited with increased right lumbar pain

termittent right lumbar burning and daily) for contraception. Her work at end-range. Left side bending was

pressure. The patients symptoms activities were sitting at a computer limited, and her right lumbar pain

were characterized by a sudden on- 8 hours a day, and she had a 1-hour was worse at end-range. Right side

set when standing after sitting for 3 commute to and from work. Her ex- bending was normal and status quo.

hours at her computer. She rated her ercise program included jogging, us- Prone hip medial (internal) rotation

symptoms as 8/10 at worst, 0/10 at ing the elliptical machine, and ab- PROM was 56 degrees on the left and

best, and 5/10 at the time of her dominal curls with a floor-exercise 54 degrees on the right, and lateral

examination. Aggravating activities apparatus. The patients goal was to (external) rotation was 46 degrees

included sitting 2 hours or longer, sit 5 hours at work unlimited by on the left and 48 degrees on the

sleeping supine for 1 hour or longer, pain. right. Straight leg raise was negative

jogging longer than 45 minutes, and with 96 degrees of PROM on the left.

weight bearing on her right lower Examination Straight leg raise on the right was

extremity. She usually awakened The patients initial Roland-Morris positive for reproduction of LBP at

without pain in the morning and ex- Disability Questionnaire (RMQ)15,18,32 88 degrees, and it was unchanged

perienced her symptoms after sitting score was 5/24. The RMQ was se- with dorsiflexion sensitizers. Tender-

at work. Her symptoms continued to lected prior to the case due to its ness and restrictions were noted

worsen throughout the day. She also sensitivity to change in people with with palpation of the right lumbar

reported a secondary concern of acute LBP.18 The patients FABQ paraspinals. The right L5-S1 segment

burning right lateral leg pain that scores were 18/42 for the work was hypomobile and reproduced her

she experienced intermittently dur- subscale and 9/24 for the physical lumbar pain. The left L5-S1 segment

ing the last year. This pain began activity subscale, indicating low was hypomobile and pain-free. The

insidiously 1 year previously, concur- fear-avoidance beliefs. Her LoBACS L12 through L4 5 segments had

rently with multiple brief episodes scores were 86%, 100%, and 90% for normal mobility, which was painful

of LBP. Her episodic LBP resolved, the function, self-regulatory, and ex- on the right and pain-free on the left.

but the leg pain remained aggravated ercise subscales, respectively.

with jogging, driving or prolonged Evaluation

sitting. The patient displayed decreased tho- Based on the initial examination

racic kyphosis, increased lumbar lor- data, the mediators influencing the

At the time of intake, she reported dosis, and greater prominence of the patients acute LBP were categorized

that her leg pain increased as her right lumbar paraspinal musculature and ranked above using the ICF

right LBP increased. Her symptoms with visual postural assessment. Ini- model (Tab. 2). The patient met 4 of

eased with changing positions from tial pain in a standing position was the 5 criteria that predict success

sitting or supine, using her elliptical 1/10 located at the right lumbar with manipulation in patients with

machine, and using her abdominal spine and lateral leg. During right LBP, and she did not have any signs

exercise equipment. She slept with- single-leg stance, the patient had in- of nerve root compression. Research

out disturbance in a side-lying posi- creased lumbar pain and increased suggesting she had a 92% chance of a

tion. The patient stated that her pain pelvic drop with trunk rotation. Left successful outcome with lumbopel-

intensity had diminished since initial single-leg stance was pain-free with a vic manipulation prioritized her re-

onset. She reported having no numb- level pelvis. Myotomal lower-quarter duced mobility of joint functions as

ness or paresthesias in her lower ex- strength screening revealed the the primary body function limita-

tremities, change in bowel or blad- L1-L5 innervated muscles were tion.33 We hypothesized that the re-

der function, saddle paresthesia, or graded as 5/5 and equal bilaterally. duced mobility of joint function at

weakness or incoordination in the The S1 myotome testing demon- L5S1 on the right and the resulting

lower extremities. Significant medi- strated 8 unilateral heel-raises on sensations of pain were contributing

cal history included anxiety disorder the left and 6 unilateral heel-raises to her limitations with maintaining

and depression. Medications in- on the right, with right heel-raise body positions and movement. Her

cluded ibuprofen (600 mg 3 times performance limited by leg pain limited movement and sensation of

daily, as needed) for pain and inflam- rather than weakness. Dermatomal pain contributed to her restrictions

mation, nortriptyline (600 mg 3 light touch was normal. Patellar and in regular recreation activities. The

86 f Physical Therapy Volume 89 Number 1 January 2009

Downloaded from http://ptjournal.apta.org/ by guest on January 22, 2015

Low Back Pain and the WHO-ICF Model

Table 2.

The World Health Organizations International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (WHO-ICF) Model Applied to the

Evaluation of Patient 2 (Acute Low Back Pain)a

Body Structures and Functions Activities Participation

Patients perspective Pain in back Sitting 2 h Limited exercise program

Pain in leg Lying supine 1 h Interruption of work

Jogging 45 min

Physical therapists perspective 1. Reduced mobility of joint functions 1. Maintaining body position 1. Recreation and leisure (d920)

(b710) (d410)

2. Sensation of pain (b280) 2. Moving around (b455) 2. Remunerative employment (d850)

3. Control of voluntary movement

functions (b760)

4. Neural tissue provocation

Contextual Factors

Personal

No personal factors were deemed to be barriers as measured by the selected questionnaires

Facilitators: activity level and continuation of exercise

Environmental

Health professionals (e355)

Products and technology for employment (e135)

Labor and employment services, systems, and policies (e590)

Transportation services, systems, and policies (e590)

a

Mobility of joint functions and sensation of pain were ranked as the primary body functions because the patient met the clinical prediction rule for

manipulation. It was hypothesized that these impaired body functions were contributing to her limitations with maintaining body positions and movement,

thereby restricting her participation in regular recreational activities. Neural provocation was prioritized next because the slump test reproduced her leg

pain. Control of voluntary movement functions was considered to reduce the likelihood of reoccurring episodes of low back pain.

contextual factor of the health care lying manipulation technique di- environmental barrier of sitting for

professionals awareness and appli- rected at L5S1 on the right to work. During visit 2, testing of prone

cation of research evidence was improve mobility of joint function hip extension with knee extended

thought to positively mediate her re- and reduce sensation of pain.34 Sub- on the right revealed anterior pelvic

habilitation. A significant bidirec- sequently, the patient was instructed rotation and right ilium anterior ro-

tional relationship in this case was in a home exercise program of left tation in the transverse plane, indi-

between the requirement of sitting side lying with right trunk rotation cating a lack of lumbopelvic neuro-

at a computer for 8 hours for em- AROM. She was educated on sitting muscular control. This was the only

ployment and her sensation of pain. posture and ergonomics for com- remaining impaired body function at

Pain limited her ability to maintain puter use to address the potential visit 3. The patient was prescribed

this body position, but the duration environmental barrier of prolonged prone hip extension stabilization ex-

of sitting required for her work led sitting at a computer for work. Dur- ercise to address this impairment.

to increased pain intensity. The pa- ing the second visit, the side-lying

tient was given an excellent progno- manipulation was repeated. Further Outcome

sis due to the strong research evi- examination revealed a negative SLR, Immediate improvement was dem-

dence for her improvement with but slump testing was positive for onstrated after the initial manipula-

manipulation. LBP and increased right leg pain. The tion, with 0/10 lumbar and leg pain

patient was instructed in a self- in standing, no pain with lumbar ex-

Intervention administered AROM exercise in the tension AROM, decreased pain with

The patient received 3 treatment ses- test position to address the associ- left side-bending AROM, and no pain

sions over 23 days. She was educated ated reduced nerve mobility and sen- with right single-leg stance. At the

on her physical therapists diagnosis, sation of pain. She was instructed to second visit, her right LBP and leg

prognosis, and plan of care. The ini- take a standing break from sitting pain were less intense (ie, 2/10 at

tial intervention involved a left side- every hour at work to minimize the worst). Extension created right lum-

January 2009 Volume 89 Number 1 Physical Therapy f 87

Downloaded from http://ptjournal.apta.org/ by guest on January 22, 2015

Low Back Pain and the WHO-ICF Model

bar pain at end-range, and right and consequent LBP. The WHO-ICF curred by monitoring the effective-

L5S1 accessory motion was still model may predict the potential ness of the interventions using vari-

painful and hypomobile. She was success of physical therapy inter- ous outcome assessments from the

able to sit 5 hours at work without ventions for other symptom-based examination to measure change in

LBP, and her RMQ score was 1/24. health conditions in which a spe- activities and participation. Ques-

During the final visit, the patient re- cific, tissue-based pathology is tionnaires with acceptable psycho-

ported no pain since the day of the unclear. metrics allowed accurate measure-

last treatment. She was working a ment of patient perceptions in order

full day and returned to jogging with- Patients in this case report series to evaluate and modify the hypothe-

out pain. Her final RMQ score was benefited from the WHO-ICF mod- ses developed within the WHO-ICF

0/24. Her LoBACS scores were 91%, els explicit acknowledgment of per- framework as the rehabilitation cy-

100%, and 100% for the function, sonal and environmental factors as cles continued. In addition to the

self-regulatory, and exercise sub- important contributors to disable- concept of the rehabilitation cycle,

scales, respectively. Her FABQ ment through their interaction with evidence-based practice principles

scores were 5/42 for the work sub- the physical domains. For the patient were used to identify the best possi-

scale and 4/24 for the physical activ- with chronic LBP, a belief related to ble examination, evaluation, and in-

ity subscale. Re-examination demon- avoidance of physical activity was a tervention strategies.37 Classifying

strated normal lumbar AROM, negative personal factor. Recogniz- acute LBP into treatment-based cate-

normal and pain-free accessory mo- ing this negative personal factor al- gories based on clinical presentation

tion testing, and a negative slump lowed the therapist to direct specific has been associated with superior

test. The patient was discharged educational interventions designed outcomes compared with non-

from physical therapy with all goals to reduce her fear-avoidance behav- matched treatments.33,38 Clearly, al-

met. ior and secondarily her participation though the WHO-ICF provides a

restrictions. Environmental factors powerful new tool for physical ther-

Discussion also played a large role in both cases. apists, existing clinical reasoning

The WHO-ICF model is character- In the patient with chronic LBP, the models may be expected to retain

ized by a bidirectional flow of infor- structural setup of her workspace, complementary roles in the clinical

mation rather than hierarchical orga- the use of a computer for work, and reasoning process by physical

nization of its domains. This was the requirements that she transport therapists.

demonstrated with several hypothe- files contributed to her participation

sized bidirectional relationships in at work. The requirement that the This case report provided 2 exam-

the 2 cases. The WHO-ICF model ap- woman with acute LBP sit and work ples of the application of the WHO-

pears to provide an effective frame- at a computer 8 hours a day for her ICF model in patients with LBP. It

work for physical therapists to better job greatly played a part in her provides preliminary evidence for

understand each persons experi- disability. the clinical utility of the bidirectional

ence with his or her disablement and relationships among the WHO-ICF

assist in prioritizing treatment selec- Existing clinical reasoning models models domains, explicit acknowl-

tion. It is notable that the health con- were used concurrently with the or- edgment of personal and environ-

dition identified in this case series ganization of function provided by mental factors that affect disable-

was LBP, which is a symptom-based the WHO-ICF model (Fig. 2). For ex- ment, and potential complementary

condition rather than a specific, ample, Edwards and colleagues clin- clinical reasoning models. Future re-

tissue-based pathology.35 The WHO- ical reasoning model36 was used to search is necessary to apply the

ICF model assisted in identifying organize the appropriate perfor- WHO-ICF model to other body re-

body structure and function deficits mance of the functions of the phys- gions and health conditions common

and activity limitations. Interven- ical therapist. A hypothesis was de- in physical therapist practice. This

tions directed at these impairments, veloped from history and physical research should establish the clinical

contextual factors, and limitations examination data, the therapists effectiveness of its application and

addressed the health condition and knowledge, and the patients experi- derive core sets that may be useful

appeared to affect activity and par- ence. After the evaluation, the ther- for optimal education, research, and

ticipation. For example, the hip apist selected the best possible inter- reimbursement.

muscle performance and length def- ventions based on research, clinical

icits observed in the patient with experience, and patient preference

Dr Rundell and Dr Davenport provided con-

chronic LBP were hypothesized to that matched the previously selected cept/idea/project design, writing, and data

result in poor segmental stabilization components. Reassessment oc-

88 f Physical Therapy Volume 89 Number 1 January 2009

Downloaded from http://ptjournal.apta.org/ by guest on January 22, 2015

Low Back Pain and the WHO-ICF Model

Figure 2.

Integrated model of physical therapist clinical reasoning incorporating the World Health Organizations International Classification of

Functioning, Disability and Health (WHO-ICF) model, with important concepts from Sacketts principles of evidence-based practice,37

the rehabilitation cycle, and Edwards and colleagues clinical reasoning model of physical therapists.36

analysis. Ms Wagner assisted in the project the Kaiser Permanente Southern California affirm that they have no financial affiliation

design. Dr Rundell provided data collection, Orthopaedic Physical Therapy Residency. or involvement with any commercial organi-

project management, and patients. Dr Dav- The authors thank Joe Godges, PT, DPT, zation that has a direct financial interest in

enport and Ms Wagner provided consulta- OCS, for his insightful comments regarding any matter included in the article.

tion (including review of manuscript before an early version of the manuscript. The au-

submission). thors also gratefully recognize Kris M Keller, This article was received April 16, 2008, and

PT, Department Administrator, and Justin W was accepted October 3, 2008.

Dr Rundell completed this case report series Hamilton, PT, MPT, OCS, for their adminis-

in partial fulfillment of the requirements of trative support of this project. The authors DOI: 10.2522/ptj.20080113

January 2009 Volume 89 Number 1 Physical Therapy f 89

Downloaded from http://ptjournal.apta.org/ by guest on January 22, 2015

Low Back Pain and the WHO-ICF Model

References 15 Grotle M, Brox JI, Vollestad NK. Concur- 26 Van Dillen LR, McDonnell MK, Fleming

rent comparison of responsiveness in pain DA, Sahrmann SA. Effect of knee and hip

1 Deyo RA, Mirza SK, Martin BI. Back pain and functional status measurements used position on hip extension range of motion

prevalence and visit rates: estimates from for patients with low back pain. Spine. in individuals with and without low back

US national surveys, 2002. Spine. 2006;31: 2004;29:E492E501. pain. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2000;30:

2724 2727. 307316.

16 Von Korff M, Jensen MP, Karoly P. Assess-

2 Hashemi L, Webster BS, Clancy EA, Volinn ing global pain severity by self-report in 27 Kendall FP, McCreary EK, Provance PG,

E. Length of disability and cost of workers clinical and health services research. et al. Muscles: Testing and Function. 5th

compensation low back pain claims. J Oc- Spine. 2000;25:3140 3151. ed. Baltimore, MD: Lippincott Williams &

cup Environ Med. 1997;39:937945. Wilkins; 2007.

17 Fairbank JC, Couper J, Davies JB, OBrien

3 Loney PL, Stratford PW. The prevalence of JP. The Oswestry low back pain disabil- 28 Sahrmann SA. Diagnosis and Treatment

low back pain in adults: a methodological ity questionnaire. Physiotherapy. 1980; of Movement Impairment Syndromes. St

review of the literature. Phys Ther. 1999; 66:271273. Louis, MO: Mosby; 2001.

79:384 396.

18 Lauridsen HH, Hartvigsen J, Manniche C, 29 Maher CG, Adams R. Reliability of pain and

4 Walker BF, Muller R, Grant WD. Low back et al. Responsiveness and minimal clini- stiffness assessments in clinical manual

pain in Australian adults: prevalence and cally important difference for pain and lumbar spine examination. Phys Ther.

associated disability. J Manipulative disability instruments in low back pain 1994;74:801 809; discussion 809 811.

Physiol Ther. 2004;27:238 244. patients. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 30 Maher CG, Latimer J, Adams R. An inves-

5 Jette AM, Smith K, Haley SM, Davis KD. 2006;7:82. tigation of the reliability and validity of

Physical therapy episodes of care for pa- 19 Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Beck De- posteroanterior spinal stiffness judgments

tients with low back pain. Phys Ther. pression Inventory II Manual. San Anto- made using a reference-based protocol.

1994;74:101110; discussion 110 105. nio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; Phys Ther. 1998;78:829 837.

6 Jette AM, Assmann SF, Rooks D, et al. In- 1996. 31 Davidson M, Keating JL. A comparison of

terrelationships among disablement con- 20 Hiroe T, Kojima M, Yamamoto I, et al. Gra- five low back disability questionnaires: re-

cepts. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. dations of clinical severity and sensitivity liability and responsiveness. Phys Ther.

1998;53:M395M404. to change assessed with the Beck De- 2002;82:8 24.

7 Jette AM, Keysor JJ. Disability models: im- pression Inventory-II in Japanese pa- 32 Roland M, Morris R. A study of the natural

plications for arthritis exercise and physi- tients with depression. Psychiatry Res. history of back pain, part I: development

cal activity interventions. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;135:229 235. of a reliable and sensitive measure of dis-

2003;49:114 120. 21 Swinkels-Meewisse EJ, Swinkels RA, Ver- ability in low-back pain. Spine. 1983;

8 Stucki G, Cieza A, Ewert T, et al. Applica- beek AL, et al. Psychometric properties of 8:141144.

tion of the International Classification of the Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia and 33 Childs JD, Fritz JM, Flynn TW, et al. A clin-

Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) in the Fear-Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire ical prediction rule to identify patients

clinical practice. Disabil Rehabil. 2002; in acute low back pain. Man Ther. with low back pain most likely to benefit

24:281282. 2003;8:29 36. from spinal manipulation: a validation

9 Stucki G, Ewert T, Cieza A. Value and ap- 22 Waddell G, Newton M, Henderson I, et al. study. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141:

plication of the ICF in rehabilitation med- A Fear-Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire 920 928.

icine. Disabil Rehabil. 2003;25:628 634. (FABQ) and the role of fear-avoidance be- 34 Gibbons P, Tehan P. Manipulation of the

liefs in chronic low back pain and disabil-

10 International Classification of Function- Spine, Thorax and Pelvis: An Osteopathic

ity. Pain. 1993;52:157168.

ing, Disability and Health: ICF. Geneva, Perspective. 2nd ed. Chatswood, NSW,

Switzerland: World Health Organization; 23 Davenport TE, Cleland JA, Lewthwaite R, Australia: Churchill Livingstone; 2005.

2001. et al. Responsiveness of the Low Back Ac- 35 Davenport TE, Watts HG, Kulig K, Resnik

tivity Confidence Scale in a subgroup of

11 Irrgang JJ, Godges J. Use of the Interna- C. Current status and correlates of physi-

patients with low back pain: preliminary

tional Classification of Functioning and cians referral diagnoses for physical ther-

analyses. Paper presented at: Combined

Disability to develop evidence-based apy. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2005;35:

Sections Meeting of the American Physical

practice guidelines for treatment of com- 572579.

Therapy Association; February 6 9, 2008;

mon musculoskeletal conditions. Ortho- Nashville, TN. 36 Edwards I, Jones M, Carr J, et al. Clinical

paedic Physical Therapy Practice. 2006; reasoning strategies in physical therapy.

18(4):24 25. 24 Yamada KA, Lewthwaite R, Popovich JM, Phys Ther. 2004;84:312330; discussion

et al. The Low Back Activity Confidence

12 Jette AM. The changing language of dis- 331315.

Scale (LoBACS): development and prelim-

ablement. Phys Ther. 2005;85:118 119. inary reliability and validity. Paper pre- 37 Sackett D, Straus S, Richardson W, et al.

13 Cieza A, Stucki G, Weigl M, et al. ICF Core sented at: Combined Sections Meeting of Evidence-Based Medicine: How to Prac-

Sets for low back pain. J Rehabil Med. the American Physical Therapy Associa- tice and Teach EBM. 2nd ed. Edinburgh,

2004(44 suppl):69 74. tion; February 14 18, 2007; Boston, MA. Scotland: Churchill Livingstone; 2000.

14 Childs JD, Piva SR, Fritz JM. Responsive- 25 Waddell G, Somerville D, Henderson I, 38 Fritz JM, George S. The use of a classifica-

ness of the numeric pain rating scale in Newton M. Objective clinical evaluation of tion approach to identify subgroups of pa-

patients with low back pain. Spine. physical impairment in chronic low back tients with acute low back pain: interrater

2005;30:13311334. pain. Spine. 1992;17:617 628. reliability and short-term treatment out-

comes. Spine. 2000;25:106 114.

90 f Physical Therapy Volume 89 Number 1 January 2009

Downloaded from http://ptjournal.apta.org/ by guest on January 22, 2015

Physical Therapist Management of Acute and

Chronic Low Back Pain Using the World Health

Organization's International Classification of

Functioning, Disability and Health

Sean D Rundell, Todd E Davenport and Tracey Wagner

PHYS THER. 2009; 89:82-90.

Originally published online November 13, 2008

doi: 10.2522/ptj.20080113

References This article cites 29 articles, 7 of which you can access

for free at:

http://ptjournal.apta.org/content/89/1/82#BIBL

Cited by This article has been cited by 5 HighWire-hosted articles:

http://ptjournal.apta.org/content/89/1/82#otherarticles

Subscription http://ptjournal.apta.org/subscriptions/

Information

Permissions and Reprints http://ptjournal.apta.org/site/misc/terms.xhtml

Information for Authors http://ptjournal.apta.org/site/misc/ifora.xhtml

Downloaded from http://ptjournal.apta.org/ by guest on January 22, 2015

Letters to the Editor

4 International Classification of Function- 6 International Classification of Diseases 8 McPoil TG, Martin RL, Cornwall MW, et al.

ing, Disability and Health: ICF. Geneva, (ICD-10). Available at: http://www.who. Heel pain-plantar fasciitis: clinical prac-

Switzerland: World Health Organization; int/classifications/icd/en/. tice guidelines linked to the International

2001. Classification of Function, Disability, and

7 Irrgang JJ, Godges J. Use of the Interna- Health from the Orthopaedic Section of

5 Cieza A, Stucki G, Weigl M, et al. ICF core tional Classification of Functioning and the American Physical Therapy Associa-

sets for low back pain. J Rehabil Med. Disability to develop evidence-based prac- tion. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2008;38:

2004(44 suppl);6974. tice guidelines for treatment of common A1A18.

musculoskeletal conditions. Orthopaedic

Physical Therapy Practice. 2006;18(4): 9 Childs JD, Cleland JA, Elliott JM, et al. Neck

2425. pain: clinical practice guidelines linked

to the International Classification of

Functioning, Disability and Health from

the Orthopaedic Section of the American

Physical Therapy Association. J Orthop

Sports Phys Ther. 2008;38:A1A34.

[DOI: 10.2522/ptj.2009.89.3.309]

Correction

Rundell SD, Davenport TE, Wagner T. Physical therapist management of acute and chronic

low back pain... Phys Ther. 2009;89:8290.

The bidirectional arrow between Activity and Contextual Factors was omitted in Figure 1: World Health

Organizations International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health model. The corrected figure

appears below. The Journal regrets the error.

HEALTH

CONDITION

ACTIVITY

Contextual

Factors:

Environment

& Personal

BODY FUNCTION

PARTICIPATION

AND STRUCTURE

Figure 1.

World Health Organizations International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health model.

[DOI: 10.2522/ptj.20080113.cx]

310 Physical Therapy Volume 89 Number 3 March 2009

You might also like

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Chapter II - Bodies of Fire - The Accupuncture MeridiansDocument41 pagesChapter II - Bodies of Fire - The Accupuncture MeridiansScott Canter100% (1)

- APECS & Paterson Posture AssessmentDocument8 pagesAPECS & Paterson Posture AssessmentGilbert Pizarro CabanatanNo ratings yet

- Ust Anatomy Mock 2015-1 PDFDocument7 pagesUst Anatomy Mock 2015-1 PDFJanna Janoras ŰNo ratings yet

- Snomed To SMDCSDocument20 pagesSnomed To SMDCSbckamalNo ratings yet

- Cream RisesDocument256 pagesCream RisesMArr TanNzNo ratings yet

- Physio OB Conduct of Labor and Delivery Caramel MacchiatoDocument10 pagesPhysio OB Conduct of Labor and Delivery Caramel MacchiatoMiguel Luis NavarreteNo ratings yet

- Case Study 2Document9 pagesCase Study 2Dyan Bianca Suaso LastimosaNo ratings yet

- Urethral InjuryDocument7 pagesUrethral InjuryIoannis ValioulisNo ratings yet

- Anterior Abdominal Wall Lecture - Nov2015Document75 pagesAnterior Abdominal Wall Lecture - Nov2015Nithin0% (1)

- SIJTwo Reducing Pain Discomfort 1Document6 pagesSIJTwo Reducing Pain Discomfort 1mikeNo ratings yet

- Lower Back Pain: Healthshare Information For Guided Patient ManagementDocument12 pagesLower Back Pain: Healthshare Information For Guided Patient Managementkovi mNo ratings yet

- Roku Dan ReportDocument20 pagesRoku Dan ReportbambangijoNo ratings yet

- Chapter 6. Axial Skeleton: I. Radiographic AnatomyDocument11 pagesChapter 6. Axial Skeleton: I. Radiographic AnatomyRindha Dwi SihantoNo ratings yet

- 2.1.1.6 Otot Dasar Panggul, Ukuran Panggul, Dan Kepala BayiDocument41 pages2.1.1.6 Otot Dasar Panggul, Ukuran Panggul, Dan Kepala BayiTessa YolandaNo ratings yet

- Wln-Normal LabourDocument45 pagesWln-Normal LabourEmmanuel MukukaNo ratings yet

- Female Genital Tract Anatomy 5th YearDocument12 pagesFemale Genital Tract Anatomy 5th Yearzianab aliNo ratings yet

- Posture in PhysiotherapyDocument31 pagesPosture in PhysiotherapyAnshuman VyasNo ratings yet

- 300 LevelDocument4 pages300 LevelAkinsola AyomidotunNo ratings yet

- SBA Part 1 MRCOGDocument247 pagesSBA Part 1 MRCOGHendra Pamukti100% (6)

- Anatomy of Female Pelvis & Fetal SkullDocument26 pagesAnatomy of Female Pelvis & Fetal SkullSalman KhanNo ratings yet

- Core Exercises 5 Workouts To Tighten Your Abs, Strengthen Your Back, and Improve Balance (Lauren E. Elson MD, Michele Stanten Etc.)Document54 pagesCore Exercises 5 Workouts To Tighten Your Abs, Strengthen Your Back, and Improve Balance (Lauren E. Elson MD, Michele Stanten Etc.)HeyitzmeNo ratings yet

- MUSCULAR SYSTEM Written ReportDocument34 pagesMUSCULAR SYSTEM Written Reportpauline cabualNo ratings yet

- Anatomy PDFDocument114 pagesAnatomy PDFkhualabear101100% (1)

- KRIYA To Expand The Lungs, Thorax by Devi AtmanandaDocument2 pagesKRIYA To Expand The Lungs, Thorax by Devi Atmananda4gen_2No ratings yet

- Skenario A Blok 17 L3 FixDocument35 pagesSkenario A Blok 17 L3 FixSelli Novita BelindaNo ratings yet

- Emailing 11. Dr. Manoj Gupta - Pelvic RT PlanningDocument69 pagesEmailing 11. Dr. Manoj Gupta - Pelvic RT PlanningafshanNo ratings yet

- Ortho Only QuestionsDocument42 pagesOrtho Only QuestionstamikanjiNo ratings yet

- Anat & Phy of Pulvic BoneeDocument59 pagesAnat & Phy of Pulvic Boneebereket gashu100% (2)

- 13 Adductor Muscle Group Excision: Martin Malawer and Paul SugarbakerDocument10 pages13 Adductor Muscle Group Excision: Martin Malawer and Paul SugarbakerSanNo ratings yet

- Coding Cheat Sheet For Residents in Outpatient MedicineDocument3 pagesCoding Cheat Sheet For Residents in Outpatient MedicineRayCTsai86% (21)