Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Declaration of The Rights of Man and of The Citizen

Uploaded by

FaithMayfair0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

26 views3 pagesx

Original Title

Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this Documentx

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

26 views3 pagesDeclaration of The Rights of Man and of The Citizen

Uploaded by

FaithMayfairx

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 3

Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, French Declaration

des Droits de lHomme et du Citoyen, one of the basic charters of human

liberties, containing the principles that inspired the French Revolution. Its 17

articles, adopted between August 20 and August 26, 1789,

by Frances National Assembly, served as the preamble to the Constitution of

1791. Similar documents served as the preamble to the Constitution of 1793

(retitled simply Declaration of the Rights of Man) and to the Constitution of

1795 (retitled Declaration of the Rights and Duties of Man and the Citizen).

The basic principle of the Declaration was that all men are born and remain

free and equal in rights (Article 1), which were specified as the rights of

liberty, private property, the inviolability of the person, and resistance to

oppression (Article 2). All citizens were equal before the law and were to have

the right to participate in legislation directly or indirectly (Article 6); no one was

to be arrested without a judicial order (Article 7). Freedom of religion (Article

10) and freedom of speech (Article 11) were safeguarded within the bounds of

public order and law. The document reflects the interests of the elites who

wrote it: property was given the status of an inviolable right, which could be

taken by the state only if an indemnity were given (Article 17); offices and

position were opened to all citizens (Article 6).

The sources of the Declaration included the major thinkers of the

French Enlightenment, such as Montesquieu, who had urged the separation

of powers, and Jean-Jacques Rousseau, who wrote of general willthe

concept that the state represents the general will of the citizens. The idea that

the individual must be safeguarded against arbitrary police or judicial action

was anticipated by the 18th-century parlements, as well as by writers such

as Voltaire. French jurists and economists such as the physiocrats had

insisted on the inviolability of private property. Other influences on the authors

of the Declaration were foreign documents such as the Virginia Declaration of

Rights (1776) in North America and the manifestos of the Dutch Patriot

movement of the 1780s. The French Declaration went beyond these models,

however, in its scope and in its claim to be based on principles that are

fundamental to man and therefore universally applicable.

SIMILAR TOPICS

Declaration of Independence

Declaration of Breda

Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR)

Bill of Rights

On the other hand, the Declaration is also explicable as an attack on the pre-

Revolutionary monarchical regime. Equality before the law was to replace the

system of privileges that characterized the old regime. Judicial procedures

were insisted upon to prevent abuses by the king or his administration, such

as the lettre de cachet, a private communication from the king, often used to

give summary notice of imprisonment.

Despite the limited aims of the framers of the Declaration, its principles

(especially Article 1) could be extended logically to mean political and

even social democracy. The Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the

Citizen came to be, as was recognized by the 19th-century historian Jules

Michelet, the credo of the new age.

Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, French Declaration

des Droits de lHomme et du Citoyen, one of the basic charters of human

liberties, containing the principles that inspired the French Revolution. Its 17

articles, adopted between August 20 and August 26, 1789,

by Frances National Assembly, served as the preamble to the Constitution of

1791. Similar documents served as the preamble to the Constitution of 1793

(retitled simply Declaration of the Rights of Man) and to the Constitution of

1795 (retitled Declaration of the Rights and Duties of Man and the Citizen).

The basic principle of the Declaration was that all men are born and remain

free and equal in rights (Article 1), which were specified as the rights of

liberty, private property, the inviolability of the person, and resistance to

oppression (Article 2). All citizens were equal before the law and were to have

the right to participate in legislation directly or indirectly (Article 6); no one was

to be arrested without a judicial order (Article 7). Freedom of religion (Article

10) and freedom of speech (Article 11) were safeguarded within the bounds of

public order and law. The document reflects the interests of the elites who

wrote it: property was given the status of an inviolable right, which could be

taken by the state only if an indemnity were given (Article 17); offices and

position were opened to all citizens (Article 6).

The sources of the Declaration included the major thinkers of the

French Enlightenment, such as Montesquieu, who had urged the separation

of powers, and Jean-Jacques Rousseau, who wrote of general willthe

concept that the state represents the general will of the citizens. The idea that

the individual must be safeguarded against arbitrary police or judicial action

was anticipated by the 18th-century parlements, as well as by writers such

as Voltaire. French jurists and economists such as the physiocrats had

insisted on the inviolability of private property. Other influences on the authors

of the Declaration were foreign documents such as the Virginia Declaration of

Rights (1776) in North America and the manifestos of the Dutch Patriot

movement of the 1780s. The French Declaration went beyond these models,

however, in its scope and in its claim to be based on principles that are

fundamental to man and therefore universally applicable.

SIMILAR TOPICS

Declaration of Independence

Declaration of Breda

Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR)

Bill of Rights

On the other hand, the Declaration is also explicable as an attack on the pre-

Revolutionary monarchical regime. Equality before the law was to replace the

system of privileges that characterized the old regime. Judicial procedures

were insisted upon to prevent abuses by the king or his administration, such

as the lettre de cachet, a private communication from the king, often used to

give summary notice of imprisonment.

Despite the limited aims of the framers of the Declaration, its principles

(especially Article 1) could be extended logically to mean political and

even social democracy. The Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the

Citizen came to be, as was recognized by the 19th-century historian Jules

Michelet, the credo of the new age.

https://www.britannica.com/topic/Declaration-of-the-Rights-of-Man-and-of-the-Citizen

You might also like

- Hypothesis Tests for Difference Between Two MeansDocument2 pagesHypothesis Tests for Difference Between Two MeansFaithMayfair0% (1)

- StarburnDocument28 pagesStarburnFaithMayfairNo ratings yet

- Writing para NarrDocument6 pagesWriting para NarrJijie Izam ZizieNo ratings yet

- Minor AwardsDocument2 pagesMinor AwardsFaithMayfair67% (6)

- Declaration of The Rights of Man and of The Citize2Document1 pageDeclaration of The Rights of Man and of The Citize2FaithMayfairNo ratings yet

- Criteria FinalDocument2 pagesCriteria FinalFaithMayfairNo ratings yet

- Election Law Case DigestsDocument34 pagesElection Law Case DigestsFaithMayfairNo ratings yet

- Declaration of The Rights of Man and of The Citize4Document4 pagesDeclaration of The Rights of Man and of The Citize4FaithMayfairNo ratings yet

- Filipino 3 - Power of Your LoveDocument3 pagesFilipino 3 - Power of Your LoveFaithMayfairNo ratings yet

- Self Defense (Beninsig Vs People)Document3 pagesSelf Defense (Beninsig Vs People)FaithMayfairNo ratings yet

- #Corruption #Unemployment #Extrajudicialkillin GsDocument2 pages#Corruption #Unemployment #Extrajudicialkillin GsFaithMayfairNo ratings yet

- 4 Points 3 Points 3 Points Total 10 Points 4 PointsDocument3 pages4 Points 3 Points 3 Points Total 10 Points 4 PointsFaithMayfairNo ratings yet

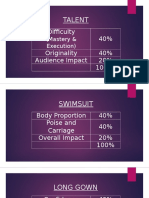

- Difficulty 40% Originality 40% Audience Impact 20% 100 %: TalentDocument5 pagesDifficulty 40% Originality 40% Audience Impact 20% 100 %: TalentFaithMayfairNo ratings yet

- 3 Points 3 Points 2 Points 2 Points Total 10 Points 4 Points 3 Points 3 Points Total 10 PointsDocument2 pages3 Points 3 Points 2 Points 2 Points Total 10 Points 4 Points 3 Points 3 Points Total 10 PointsFaithMayfairNo ratings yet

- Walker APSR 1966Document12 pagesWalker APSR 1966Agnes BalintNo ratings yet

- JudicialDocument123 pagesJudicialevelina88100% (1)

- JudicialDocument123 pagesJudicialevelina88100% (1)

- Cayetano Vs Monsod DigestDocument2 pagesCayetano Vs Monsod DigestFaithMayfairNo ratings yet

- H2o CycleDocument9 pagesH2o CycleFaithMayfairNo ratings yet

- Cayetano Vs Monsod DigestDocument2 pagesCayetano Vs Monsod DigestFaithMayfairNo ratings yet

- 10.introduction To Hypothesis TestingDocument2 pages10.introduction To Hypothesis TestingFaithMayfairNo ratings yet

- 11.hypothesis Test For A Single MeanDocument2 pages11.hypothesis Test For A Single MeanFaithMayfair100% (1)

- Application For Industrial Sand and Gravel Permit (Isag) No.Document3 pagesApplication For Industrial Sand and Gravel Permit (Isag) No.FaithMayfairNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Assignment TpaDocument8 pagesAssignment TpaatulNo ratings yet

- BibliographyDocument3 pagesBibliographyapi-220127781No ratings yet

- On Christian Love For The YouthDocument19 pagesOn Christian Love For The YouthLuisa SemillanoNo ratings yet

- Chamber Judgment Moreno Gomez v. Spain 16.11.04Document3 pagesChamber Judgment Moreno Gomez v. Spain 16.11.04Antonia NicaNo ratings yet

- Useful Phrases For Writing EssaysDocument4 pagesUseful Phrases For Writing EssaysAlexander Zeus100% (3)

- Report Samsung HR PracticesDocument5 pagesReport Samsung HR Practicesmajid896943% (14)

- HUMAN RIGHTS LAW CHAPTERSDocument5 pagesHUMAN RIGHTS LAW CHAPTERSMegan Mateo80% (10)

- Cachanosky, N. - CV (English)Document9 pagesCachanosky, N. - CV (English)Nicolas CachanoskyNo ratings yet

- Suzara Vs BenipayoDocument1 pageSuzara Vs BenipayoGui EshNo ratings yet

- Consumer Response To Corporate Irresponsible Behavior - Moral Emotions and VirtuesDocument8 pagesConsumer Response To Corporate Irresponsible Behavior - Moral Emotions and VirtuesmirianalbertpiresNo ratings yet

- 1993 Bar Questions Labor StandardsDocument8 pages1993 Bar Questions Labor StandardsJamie Dilidili-TabiraraNo ratings yet

- Internet CensorshipDocument7 pagesInternet Censorshipapi-283800947No ratings yet

- Appraisal: BY M Shafqat NawazDocument28 pagesAppraisal: BY M Shafqat NawazcallNo ratings yet

- Mutual Non Disclosure AgreementDocument3 pagesMutual Non Disclosure AgreementRocketLawyer78% (9)

- BVB0033270 PDFDocument6 pagesBVB0033270 PDFMohd Fakhrul Nizam HusainNo ratings yet

- ICTAD Procurement of Work ICTAD SBD 01-2007Document80 pagesICTAD Procurement of Work ICTAD SBD 01-2007Wickramathilaka198196% (146)

- Court Case Dispute Between Feati University and Faculty ClubDocument17 pagesCourt Case Dispute Between Feati University and Faculty ClubJoyelle Kristen TamayoNo ratings yet

- Debt Collector Disclosure StatementDocument5 pagesDebt Collector Disclosure StatementBhakta Prakash94% (16)

- Reactions To I Cant Stop Lying by Foodie BeautyDocument3 pagesReactions To I Cant Stop Lying by Foodie BeautyJing DalaganNo ratings yet

- Bonifacio Nakpil vs. Manila Towers Development Corp., GR No. 160867, Sept 20, 2006Document2 pagesBonifacio Nakpil vs. Manila Towers Development Corp., GR No. 160867, Sept 20, 2006Addy Guinal100% (3)

- Research Proposal for Minor Research ProjectsDocument13 pagesResearch Proposal for Minor Research ProjectsDurgesh KumarNo ratings yet

- 2017 11 19 - CE483 CE583 Con Cost Estimating Syllabus - v2 - 0Document6 pages2017 11 19 - CE483 CE583 Con Cost Estimating Syllabus - v2 - 0azamgabirNo ratings yet

- R&D Tax CreditDocument7 pagesR&D Tax Creditb_tallerNo ratings yet

- Quality Management, Ethics, and Corporate Social ResponsibilityDocument31 pagesQuality Management, Ethics, and Corporate Social ResponsibilityRaghad MasarwehNo ratings yet

- Labor Law Review Usec. JBJDocument14 pagesLabor Law Review Usec. JBJLevz LaVictoriaNo ratings yet

- Brown Creative Vintage Rustic Motivational Quote PosterDocument2 pagesBrown Creative Vintage Rustic Motivational Quote PosterAthenaNo ratings yet

- Freedom Summer Read AloudDocument3 pagesFreedom Summer Read AloudCassandra Martin0% (1)

- Dialogic OD Approach to TransformationDocument12 pagesDialogic OD Approach to Transformationevansdrude993No ratings yet

- Benefits and Drawbacks of Using the Internet for International ResearchDocument2 pagesBenefits and Drawbacks of Using the Internet for International ResearchAMNANo ratings yet

- Parental Authority With AnalysisDocument55 pagesParental Authority With AnalysismasdalNo ratings yet