Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Quercus Robur Petraea

Uploaded by

whybotheridkCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Quercus Robur Petraea

Uploaded by

whybotheridkCopyright:

Available Formats

Quercus robur and Quercus petraea

Quercus robur and Quercus petraea in Europe: distribution, habitat, usage and threats

E. Eaton, G. Caudullo, S. Oliveira, D. de Rigo these oaks can mix, compete and naturally hybridise with other

Mediterranean oaks, such as Quercus pubescens and Quercus

Quercus robur L., (pedunculate oak) and Quercus petraea (Matt.) Liebl., (sessile oak) are common broadleaved tree frainetto, even if at relatively low rates12 . Both oaks occur at

species in Europe, found from Scandinavia to the Iberian Peninsula. The two species are quite similar in appearance and higher elevations in southern regions: Q. robur is recorded to grow

have a broadly overlapping range. Oak trees have cultural significance for people throughout Europe and the trees or up to 1300m in the Alps13, while Q. petraea is more montane

leaves are frequently used in national or regional symbols. Oak trees can live for more than 1000 years and grow to and in southern Turkey can reach over 2000m4, 14, 15 . Due to the

be 30 to 40m in height. The wood from oaks is hard and durable and has been valued for centuries. It is favoured for substantial human interest and usage of the species over many

construction and for wine and spirit barrels; historically it was a major source of ship timbers. Recently, concerns have centuries, there is widespread disturbance in their distribution, and

arisen about the fate of oaks in the face of Acute Oak Decline, a little understood syndrome. the structure of their original forests is highly uncertain16 . Q. robur

Quercus robur L., known as pedunculate or English oak, and has been introduced into the United States for timber production

Quercus petraea (Matt.) Liebl., known as sessile oak, are large, and in some areas it has naturalised; more recently they have been

rugged, deciduous broadleaved trees, native to most of Europe. Frequency

< 25%

exported into other continents as ornamental trees17, 18 .

Individuals can be very long-lived (over 1000 years in some cases) 25% - 50%

and become large (over 40m tall), attaining diameters of three to

50% - 75%

> 75%

Habitat and Ecology

four metres1-3 . More usually, these oaks achieve a height of 30m Chorology Q. robur and Q. petraea co-occur at many sites as a main

and diameters of up to 1m4 . These two tree species, as well as

Native

component of temperate deciduous mixed forests, and they

other oaks, are very variable morphologically, and can naturally share several common characteristics. These oaks are vigorous

hybridise, generating individuals showing intermediate traits or trees with a large ecological amplitude, although they prefer

the prevalence of one, so that it can be difficult to characterise fertile and moist soils, and are able to dominate forests in

them unequivocally by observations alone5, 6 . The main trunk of number and size at low-mid elevations19 . Both are able to behave

Q. robur tends to disappear in the crown, developing irregular as pioneer trees, the acorns possessing large reserves and

boughs with twisting branches, while Q. petraea usually develops able to survive amongst grasses whilst developing sufficiently

a main stem with boughs gradually deceasing in size7. The barks deep roots to allow rapid shoot growth2, 10 . As these trees do

are grey, fissured, forming rectangular elongate blocks, which not come into leaf until relatively late in the year (late April

are thicker in Q. robur, while those of Q. petraea often tend to to early May), late frost damage is rarely a problem, unless

exfoliate7. The leaves are simple, obovate-oblong and deeply and the temperatures reach -3C killing new foliage2, 10 . Sustained

irregularly lobed, with a short stalk (2-7mm) in Q. robur and a temperatures below -6C in winter can kill acorns, despite the

long stalk (13-25mm) in Q. petraea. These oaks are monoecious epicotyl requiring some chilling to break its dormancy10 . Both

and wind-pollinated, with drooping male flowers in yellow catkins Map 1-A: Plot distribution map (Q. robur). oaks have a good re-sprouting aptitude, so they coppice and

about 5cm long and inconspicuous globular female flowers of Frequency of Quercus robur occurrences within the field observations as pollard easily2, 7. Their deep and penetrating taproots (more

reported by the National Forest Inventories. The chorology of the native

1mm at terminal shots, which appear just after the first leaves spatial range for Q. robur is derived after EUFORGEN45 . developed in Q. petraea) give them structural stability against

have flushed8 . The fruits are the acorns, which are often in pairs windthrow and allow them to withstand moderate droughts by

and sit in scaly cups on the ends of long stalks in Q. robur and accessing deeper water2, 10 . However, in conditions far from their

on short or absent stalks in Q. petraea, giving rise to its common Distribution optimum, they show ecological differences. The tendency is for

name sessile, meaning stalkless. The acorns are very variable Both oaks occur widely across most of Europe, reaching Q. robur to grow on heavier soils in more continental climates, in

in size and shape, but those of Q. robur are usually smaller northwards to southern Norway and Sweden, and southwards to wet lowlands and damp areas by streams and rivers, tolerating

and rounded with olive-green longitudinal stripes visible when the northern part of the Iberian Peninsula, South Italy, the Balkan periodic flooding. The more drought tolerant Q. petraea prefers

fresh7. Mammals and birds are important for the seed dispersal, Peninsula and Turkey. They are sympatric in many parts of their to grow in more Atlantic climates on light and well-drained, often

especially the Eurasian jay (Garrulus glandarius) which can be range. Q. robur has a more extended distribution, reaching more rocky, soils (hence the specific Latin name petraea = of rocky

considered the primary propagator9, 10 . northerly ranges on the Norwegian coast and in northern Scotland; places), generally occurring on slopes and hill tops, and preferring

in Mediterranean areas it is also present in Portugal, Greece and a more acid soil pH2, 7, 10, 15, 20 . They are both light-demanding

South Turkey, and eastwards into continental central Russia, up to trees (Q. robur more so than Q. petraea)2, 10 , and their canopies

the Urals7, 11 . The southerly range limits are difficult to define, as permit a good deal of light to pass through to the undergrowth,

promoting the regeneration of many tree species and enriching

Uncertain, no-data

Marginal/no presence < 5%

Low presence 5% - 10%

Mid-low presence 10% - 30%

Medium presence 30% - 50%

Mid-high presence 50% - 70%

High presence 70% - 90%

Very-high presence > 90%

Stalkless acorns of sessile oak (Quercus petraea).

(Copyright AnRo0002, commons.wikimedia.org: CC0)

Map 2-A: High resolution distribution map estimating the relative probability of presence for Quercus robur. Acorn of pedunculate oak (Quercus robur) with long stalk.

(Copyright Graham Calow, www.naturespot.ork.uk: AP)

160 European Atlas of Forest Tree Species | Tree species

Quercus robur and Quercus petraea

forest diversity19 . These oaks rarely form pure forests under

natural conditions. Their substantial competitor is represented

by beech (Fagus sylvatica) and in a minor way other shade or

half-shade trees, in the presence of which the oaks are unable Uncertain, no-data

to predominate as they are at a disadvantage. Typically, oaks Tundra, cold desert

dominate in damp to wet and nutrient-rich soils, where they

Negligible survivability

occur principally with hornbeam (Carpinus betulus) and other

deciduous tree species such as ash (Fraxinus excelsior, Fraxinus Low survivability

angustifolia), maple (Acer campestre, Acer platanoides) and Mid-low survivability

small-leaved lime (Tilia cordata). In these oak-hornbeam forest

Medium survivability

communities, assigned to the Carpinion betuli alliance, beech is

out of its range, or replaced as the soils are relatively dry and Mid-high survivability

warm or too wet. On warmer dry sites in sub-Mediterranean High survivability

regions, Q. petraea tends to mix with Q. pubescens and with other

drought-tolerant tree species, forming communities belonging to

the order of Quercetalia pubescenti-petraeae. In poor and acid

soils, where beech is unable to regenerate, oaks form mixed

forests belonging to Quercetea robori-petraea communities,

which are relatively small and scattered inside the beech range.

Oaks are also present in many other forest types as secondary

species, principally in beech forests at low elevations, where soils

and climate conditions are still favourable to oaks19, 21, 22 .

Importance and Usage

Since the earliest times, these oaks have held an important

role in human culture in Europe, providing wood for fuel, acorns

for livestock, bark for tanning, and timber for construction. From

the Greeks to the Germans, Slavs and Celts, the oak was a sacred

tree15 and this is why oak is frequently a national or regional

symbol, e.g. it has appeared on German, Croatian and British

coins, and in the coat of arms of Bulgaria. The increasing demand

for oak wood products and the reduction of natural forests have

influenced the development of modern silviculture23 . Due to their

capacity to produce large volumes of valuable timber, oak stands

Map 3: High resolution map estimating the maximum habitat suitability for Quercus robur.

are frequently managed either as high forest or as coppice with mechanical stresses)10, 31, 32 . Furthermore promoting an abundant

standards23-27. Pedunculate and sessile oaks are amongst the and uniform natural regeneration is also crucial10, 15, 20, 33, 34 .

most economically important deciduous forest trees in Europe, In coppices, oaks provide a valuable source of firewood and

providing high quality hardwood for construction and furniture charcoal, and in the past the bark has been much used in the

manufacture2 . Q. petraea wood is largely indistinguishable from tanning of leather10 . Several cultivars have been selected for

that of Q. robur and is particularly appreciated for its straight ornamental purposes, especially from Q. robur, and exported

grain, its durability thanks to its hardness, and its high tannin all over the world. Oaks are particularly appreciated as park or

content, which makes it resistant to insect and fungal attacks28, 29 . roadside trees for their size and shade. Quercus robur Fastigiata

Oaks have traditionally been used in timber-framed buildings, is one of the most common cultivars, large in size and with a

as well as for fencing, gates and mining timber, and in the past columnar cypress-like habit; Quercus petraea Laciniata has

it was the most important wood used in the manufacture of long narrow and deeply incised leaves4 . These tree species also

wooden sailing vessels7. Furniture, floor-boards, panelling, joinery have an important ecological role, as they support many species

and veneer are also important uses of the wood10 . As the wood of insects such as moths, wood-boring beetles and gall-forming

is resistant to liquids, it has been used for barrels for wines and hymenoptera, and the acorns provide a valuable food source for

spirits, where the flavour imparted by the wood is often much many birds and mammals, such as jays, mice, squirrels and pigs10 .

desired13, 30 . The most valuable oak wood has narrow rings and is

produced in high mixed forests on fertile sites with long economic

rotations (about 160 years of age for Q. petraea, about 130

years for Q. robur)2 . Successful oak silviculture requires particular

attention, selecting the proper deciduous tree species mixture,

proportion and density, which strongly influence the wood quality

with regard to tree diameters, ring widths and the presence of

wood knots formed by lateral epicormic shoots. Choice of site

and management is also important to minimise the number of

trees with shake (the development of circular or radial cracks

through the timber, which substantially reduces its value and

Large pedunculate oak (Quercus robur) in Dunkeld Hilton park (Scotland). which is influenced by a number of factors including soil type and

(Forestry Commission, www.forestry.gov.uk: Crown Copyright)

Autoecology diagrams based on harmonised field

Field data in Europe (including absences) Observed presences in Europe observations from forest plots for Quercus robur.

Average temperature of the coldest month (C)

Sum of precipitation of the driest month (mm)

Bud of sessile oak (Quercus petraea) in late winter.

(Copyright Sten Porse, commons.wikimedia.org: CC-BY)

Annual precipitation (mm)

Threats and Diseases

Defoliation of the first flush of leaves is common by

several caterpillars, e.g. Tortrix viridana, Lymantria dispar,

Operophtera brumata2 . A second leaf crop (known as St Johns

or Lammas growth, depending on its timing) is usual. As a result

of particularly heavy infestations, especially when combined

with oak mildew (Erysiphe alphitoides syn. Microsphaera

alphitoides), an oaks productivity can be seriously limited, as

the mildew covers the remaining leaf surfaces, preventing light

Annual average temperature (C) Potential spring-summer solar irradiation (kWh m-2) Seasonal variation of monthly precipitation (dimensionless)

Tree species | European Atlas of Forest Tree Species 161

Quercus robur and Quercus petraea

oaks, and this has become a more widely recognised problem in

recent years. It is characterised by a decrease in the density of

the crown, the appearance of dark oozing wounds (bleeds) on

the trunk, and in most cases the presence of the jewel beetle

Agrilus biguttatus. This syndrome can kill trees over the course

of a number of years39 . Whilst not yet fully understood, it may

be the consequence of an assemblage of contributing human,

environmental and biotic factors, such as lowering ground water

table or absence of flooding, air and water pollution, non-adapted

silvicultural practices, and climate change (e.g.40-44).

300 year old sessile oak (Quercus petraea) in Rigney (eastern France).

(Copyright Arnaud 25, commons.wikimedia.org: PD)

reaching them7, 10 . In recent years, oak processionary moth squirrels10 . Pedunculate and sessile oaks are vulnerable to

(Thaumetopoea processionea) has spread from its native Lymantria dispar and moderately susceptible to Cryphonectria

habitat in southern Europe further north35 . This caterpillar parasitica37. They both suffer because of root pathogens of the

defoliates oaks and sheds micro hairs that are a serious irritant oomycete genus Phytophthora (P. cinnamomi, P. ramorum, P.

to the human respiratory system, eyes and skin. Knopper gall quercina)37. Phytophthora ramorum has been known to cause

wasps (Andricus quercuscalicis) cause some damage to acorn extensive damage and mortality in North America, known as

crops36 . Young oak trees often have their bark stripped by grey Sudden Oak Death. Although this pathogen has been detected

in Europe, it has not yet had a substantial effect on native

European oaks and it is under observation38 . Acute Oak Decline Bark of a sessile oak (Quercus petraea).

is a new syndrome affecting principally pedunculate and sessile (Copyright Stefano Zerauschek, www.flickr.com: AP)

Uncertain, no-data

Marginal/no presence < 5%

Low presence 5% - 10%

Mid-low presence 10% - 30%

Medium presence 30% - 50%

Mid-high presence 50% - 70%

High presence 70% - 90%

Very-high presence > 90%

Maturing catkins of pedunculate oak (Quercus robur) in spring.

(Copyright AnRo0002, commons.wikimedia.org: CC0)

Frequency

< 25%

25% - 50%

50% - 75%

> 75%

Chorology

Native

Map 1-B: Plot distribution map (Quercus petraea).

Frequency of Quercus petraea occurrences within the field observations

as reported by the National Forest Inventories. The chorology of the native

spatial range for Q. petraea is derived after EUFORGEN46 . Map 2-B: High resolution distribution map estimating the relative probability of presence for Quercus petraea.

162 European Atlas of Forest Tree Species | Tree species

Quercus robur and Quercus petraea

Leaves of pedunculate oak (Quercus robur) in autumn.

(Forestry Commission, www.forestry.gov.uk: Crown Copyright)

References

[1] MonumentalTrees.com, Monumental trees [23] P.S. Johnson, S.R. Shifley, R.Rogers, eds.,

(2015). The ecology and silviculture of oaks (CABI,

[2] A.Praciak, etal., The CABI encyclopedia of Wallingford, 2002).

forest trees (CABI, Oxfordshire, UK, 2013). [24] E.Hochbichler, Annales des Sciences

[3] I.ColinPrentice, H.Helmisaari, Forest Forestires 50, 583 (1993).

Pedunculate oak (Quercus robur) in winter near Havr village (Mons, Belgium). Ecology and Management 42, 79 (1991). [25] G.K. Kenk, Annales des Sciences

(Copyright Jean-Pol Grandmont, commons.wikimedia.org: CC-BY) [4] O.Johnson, D.More, Collins tree guide Forestires 50, 563 (1993).

(Collins, 2006). [26] R.Solymos, Annales des Sciences

[5] G.Aas, Annales des sciences forestires Forestires 50, 607 (1993).

50, 107s (1993). [27] G. Decocq, Biodiversity & Conservation 9,

[6] J.Jensen, A.Larsen, L.R. Nielsen, 1467 (2000).

J.Cottrell, Annals of Forest Science 66, [28] EN 350-2, Durability of wood and wood-

706 (2009). based products. Natural durability of

[7] E.W. Jones, Journal of Ecology 47 (1959). solid wood. Guide to natural durability

and treatability of selected wood species

[8] A.F. Mitchell, P.Dahlstrom, E.Sunesen, of importance in Europe (European

C.Darter, A field guide to the trees of Committee for Standardization, Brussels,

Britain and northern Europe (Collins, 1994).

1974).

[29] L.Meyer, etal., International

[9] I.Bossema, Behaviour 70, 1 (1979). Biodeterioration & Biodegradation 86,

[10] P.S. Savill, The silviculture of trees used in 79 (2014).

British forestry (CABI, 2013). [30] T.Garde-Cerdn, C.Ancn-Azpilicueta,

[11] A.Ducousso, S.Bordacs, EUFORGEN Trends in Food Science & Technology 17,

Technical Guidelines for genetic 438 (2006).

conservation and use for pedunculate [31] A.J.E. Price, Shake in oak: an evidence

and sessile oaks (Quercus robur/Quercus review (Forestry Commission, 231

petraea) (Bioversity International, 2003). Corstorphine Road, Edinburgh, 2015).

[12] A.L. Curtu, O.Gailing, R.Finkeldey, BMC [32] R.A. Mather, P.S. Savill, Forestry 67, 119

Evolutionary Biology 7, 218+ (2007). (1994).

[13] A.Roloff, H.Weisgerber, U.M. Lang, [33] E.Guilley, J.-C. Herv, G.Nepveu, Forest

B.Stimm, Bume Mitteleuropas: Von Aspe Ecology and Management 189, 111

bis Zirbelkiefer. Mit den Portrts aller (2004).

Bume des Jahres von 1989 bis 2010.

(Wiley-VCH, 2010). [34] G.Kerr, R.Harmer, Forestry 74, 467

(2001).

[14] H.Meusel, E.Jager, eds., Vergleichende

Chorologie der Zentraleuropischen Flora [35] E.Wagenhoff, R.Blum, K.Engel, H.Veit,

- Band I, II, III (Gustav Fischer Verlag, H.Delb, Journal of Pest Science 86, 193

Jena, 1998). (2013).

[15] G.Aas, Enzyklopdie der Holzgewchse: [36] M.J. Crawley, C.R. Long, Journal of

Handbuch und Atlas der Dendrologie, Ecology 83, 686 (1995).

A.Roloff, H.Weisgerber, U.M. Lang, [37] D.deRigo, etal., Scientific Topics Focus 2,

B.Stimm, P.Schtt, eds. (Wiley-Vch Verlag, mri10a15+ (2016).

Weinheim, 2000), vol.3. [38] N.J. Grnwald, M.Garbelotto, E.M. Goss,

[16] R. Bunce, Trees and Their Habitats: An K.Heungens, S.Prospero, Trends in

Ecological Guide to Some European Trees Microbiology 20, 131 (2012).

Grown at Westonbirt Arboretum (Forestry [39] S.Denman, N.Brown, S.Kirk, M.Jeger,

Commission Research and Development J.Webber, Forestry 87, 535 (2014).

Division, Edinburgh, 1982).

[40] J.N. Gibbs, B.J.W. Greig, Forestry 70,

[17] USDA NRCS, The PLANTS database (2015). 399 (1997).

National Plant Data Team, Greensboro,

USA, http://plants.usda.gov. [41] K.Sohar, S.Helama, A.Lnelaid, J.Raisio,

H.Tuomenvirta, Geochronometria 41

[18] K.C. Nixon, C.H. Muller, Flora of North (2014).

America North of Mexico, Flora of North

America Editorial Committee, ed. (New [42] C.deSampaioe Paiva Camilo-Alves,

York and Oxford, 1997), vol.3. M.I. daClara, N.M. deAlmeidaRibeiro,

European Journal of Forest Research 132,

[19] H.H. Ellenberg, Vegetation Ecology of 411 (2013).

Forest dominated by sessile oak (Quercus petraea) in Sierra Ancares (North Western Spain). Central Europe (Cambridge University

(Copyright Alfonso San Miguel: CC-BY) Press, 2009), fourth edn. [43] D. B. Stojanovi, T. Levani, B. Matovi,

S. Orlovi, European Journal of Forest

[20] G.Aas, Enzyklopdie der Holzgewchse: Research 134, 555 (2015).

Autoecology diagrams based on harmonised field Handbuch und Atlas der Dendrologie,

Field data in Europe (including absences) Observed presences in Europe A.Roloff, H.Weisgerber, U.M. Lang, [44] R.Siwkcki, K.Ufnalski, Forest Pathology

observations from forest plots for Quercus petraea. B.Stimm, P.Schtt, eds. (Wiley-Vch Verlag, 28, 99 (1998).

Weinheim, 2012), vol.3. [45] EUFORGEN, Distribution map of

[21] European Environment Agency, European pedunculate oak (Quercus robur) (2008).

forest types. categories and types for www.euforgen.org.

Average temperature of the coldest month (C)

Sum of precipitation of the driest month (mm)

sustainable forest management reporting [46] EUFORGEN, Distribution map of sessile

and policy, Tech. rep. (2007). oak (Quercus petraea) (2008).

[22] U.Bohn, etal., Karte der natrlichen www.euforgen.org.

Vegetation Europas; Map of the

Annual precipitation (mm)

Natural Vegetation of Europe

(Landwirtschaftsverlag, 2000).

This is an extended summary of the chapter. The full version of

this chapter (revised and peer-reviewed) will be published online at

https://w3id.org/mtv/FISE-Comm/v01/e01c6df. The purpose of this

summary is to provide an accessible dissemination of the related

main topics.

This QR code points to the full online version, where the most

updated content may be freely accessed.

Please, cite as:

Eaton, E., Caudullo, G., Oliveira, S., de Rigo, D., 2016. Quercus robur

and Quercus petraea in Europe: distribution, habitat, usage

and threats. In: San-Miguel-Ayanz, J., de Rigo, D., Caudullo, G.,

Annual average temperature (C) Potential spring-summer solar irradiation (kWh m-2) Seasonal variation of monthly precipitation (dimensionless) Houston Durrant, T., Mauri, A. (Eds.), European Atlas of Forest Tree

Species. Publ. Off. EU, Luxembourg, pp. e01c6df+

Tree species | European Atlas of Forest Tree Species 163

You might also like

- Week 4 Foundation Walls, Basement Construction, CisternsDocument5 pagesWeek 4 Foundation Walls, Basement Construction, CisternsjoanneNo ratings yet

- ESSENTIALS OF WALK-UP APARTMENTSDocument13 pagesESSENTIALS OF WALK-UP APARTMENTSViktor Mikhael Roch BarbaNo ratings yet

- Sy-Plumbing-For Print Building PermitDocument7 pagesSy-Plumbing-For Print Building PermitBryan Rudolph PascualNo ratings yet

- A3 FLOOR PLAN - Layout - 2105Document8 pagesA3 FLOOR PLAN - Layout - 2105Peter WestNo ratings yet

- For Expansion of Other Chapel Branches Access Entry Will Be The Multi-Purpose Open SpaceDocument7 pagesFor Expansion of Other Chapel Branches Access Entry Will Be The Multi-Purpose Open SpaceIc Rose2No ratings yet

- Sample Architectural PlanDocument1 pageSample Architectural PlanAl DrinNo ratings yet

- Final Building Plan 1 PDFDocument1 pageFinal Building Plan 1 PDFAnonymous kvyXvVfK50% (2)

- Kitchen: Detail 07 - Kitchen Cabinet Scale 1:5Document1 pageKitchen: Detail 07 - Kitchen Cabinet Scale 1:5Laika MagbojosNo ratings yet

- Trench Plan and Foundation DetailsDocument1 pageTrench Plan and Foundation DetailsGsUpretiNo ratings yet

- C-Purlins Spaced at 600mm O.CDocument1 pageC-Purlins Spaced at 600mm O.Calezandro del rossiNo ratings yet

- Architectural plans and documents for building permitDocument1 pageArchitectural plans and documents for building permitDrei SupremoNo ratings yet

- Day Care Center 3Document1 pageDay Care Center 3mharieNo ratings yet

- Wd1 Final Kitchen Details (Mee)Document1 pageWd1 Final Kitchen Details (Mee)Meenakshi Paul100% (1)

- Longitudinal Section: Ceiling LineDocument1 pageLongitudinal Section: Ceiling LineMJian VergaraNo ratings yet

- A06-02 Bay SectionsDocument1 pageA06-02 Bay SectionsMark John DrilonNo ratings yet

- Domestic AirportDocument46 pagesDomestic AirportZenitsu ChanNo ratings yet

- Concept BoardDocument1 pageConcept Board20-09588No ratings yet

- Dhvsu: Isip, Kenneth P. Chapel Building A-1Document1 pageDhvsu: Isip, Kenneth P. Chapel Building A-1kenneth isipNo ratings yet

- Architectural Design Process and MethodologiesDocument12 pagesArchitectural Design Process and MethodologiesJan Ryan FernandezNo ratings yet

- ArchiSource Catalog 2019 PDFDocument433 pagesArchiSource Catalog 2019 PDFArchiSource100% (1)

- Model House 1 Floor PlanDocument1 pageModel House 1 Floor PlanMark Anthony Anunciacion LumbaNo ratings yet

- Construction Details On Platform FramingDocument6 pagesConstruction Details On Platform FramingMache SebialNo ratings yet

- Construction Notes: 30 BAR. DIA. 30 BAR. DIA. 40Document1 pageConstruction Notes: 30 BAR. DIA. 30 BAR. DIA. 40MARKCHRISTMASNo ratings yet

- 1 2 SarinaglDocument26 pages1 2 SarinaglanfloniNo ratings yet

- Layers of A Floor - Anatomy, and Parts (Illustrated)Document8 pagesLayers of A Floor - Anatomy, and Parts (Illustrated)Melaine A. FranciscoNo ratings yet

- Floor plan layout under 40 charactersDocument1 pageFloor plan layout under 40 charactersKaizer DAnNo ratings yet

- Architect Job Seeker ResumeDocument1 pageArchitect Job Seeker ResumeNathalie JagnaNo ratings yet

- The Various Trusses For Hip Roof SystemsDocument2 pagesThe Various Trusses For Hip Roof SystemsDaryl BallesterosNo ratings yet

- Building plans and specifications documentDocument67 pagesBuilding plans and specifications documentcimpstazNo ratings yet

- Bungalow and Row Houses PDFDocument1 pageBungalow and Row Houses PDFSalahuddin ShaikhNo ratings yet

- Pingkian Res Permit Drawings 200212 PDFDocument5 pagesPingkian Res Permit Drawings 200212 PDFRhobbie NolloraNo ratings yet

- M201 07262017 000091 Biddoc PDFDocument32 pagesM201 07262017 000091 Biddoc PDFAr Hanz Gerome SuarezNo ratings yet

- KALINGA ARCHITECTURE FinalDocument22 pagesKALINGA ARCHITECTURE FinalStephanieDelaRosaNo ratings yet

- Roof Eave DetailDocument1 pageRoof Eave DetailBrute1989No ratings yet

- Floor plans of Adhiyaman J block student hostelDocument10 pagesFloor plans of Adhiyaman J block student hostelkartik srivastavaNo ratings yet

- Design Philosophy: PlanningDocument3 pagesDesign Philosophy: PlanningCJ OngNo ratings yet

- Construction notes and schedulesDocument1 pageConstruction notes and schedulesAeron AcioNo ratings yet

- 20x30 Shed Foundation PlanDocument1 page20x30 Shed Foundation PlanBess Adrane JurolanNo ratings yet

- Plan 1 BuildingDocument1 pagePlan 1 BuildingcimpstazNo ratings yet

- Multipurpose HallDocument15 pagesMultipurpose HallNieves Guardian100% (1)

- Calatrava WorksDocument17 pagesCalatrava WorksDarshan KansaraNo ratings yet

- P14 PDFDocument1 pageP14 PDFCyrus RivasNo ratings yet

- Sample StructuralDocument1 pageSample StructuralCherish Taguinod AliguyonNo ratings yet

- Toilet DetailsDocument1 pageToilet DetailsSanchit ShastriNo ratings yet

- Timber: Name:-Yash.H.SutharDocument35 pagesTimber: Name:-Yash.H.SutharYash SutharNo ratings yet

- Sample Complete Set of PlansDocument8 pagesSample Complete Set of PlansAira Lyn RombaoaNo ratings yet

- Matrix Diagram LayoutDocument3 pagesMatrix Diagram LayoutFelix AngeloNo ratings yet

- Block-B Staircase DetailsDocument1 pageBlock-B Staircase DetailsMurthy GunaNo ratings yet

- Living Room Design ReportDocument41 pagesLiving Room Design ReportAstraea Selene YoshidaNo ratings yet

- Ceiling DetailDocument1 pageCeiling DetailDev SharmaNo ratings yet

- Ground Floor Plan Ground Floor Plan: BalconyDocument1 pageGround Floor Plan Ground Floor Plan: Balconydummya790No ratings yet

- Steel Canopy For Parking: SectionDocument1 pageSteel Canopy For Parking: SectionAshutosh PatilNo ratings yet

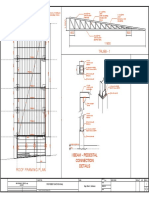

- Truss - 1: I Beam - Pedestal Connection DetailsDocument1 pageTruss - 1: I Beam - Pedestal Connection DetailslukoidsNo ratings yet

- Boys Toilet: W.C 1000x1600 W.C 1000x1600 W.C 1000x1600 W.C 1000x1600Document1 pageBoys Toilet: W.C 1000x1600 W.C 1000x1600 W.C 1000x1600 W.C 1000x1600yash ayreNo ratings yet

- Washroom Sections & DetailsDocument5 pagesWashroom Sections & DetailsyogiiinNo ratings yet

- Formoso FacadesDocument34 pagesFormoso FacadesJervis Franciscus Pendleton0% (1)

- Sample Two-Storey Floor Plan (A4)Document1 pageSample Two-Storey Floor Plan (A4)Gab RomeroNo ratings yet

- Anngran Spa Wall Finish PlanDocument1 pageAnngran Spa Wall Finish PlanMark Joseph VeranoNo ratings yet

- Building Laws Study GuideDocument5 pagesBuilding Laws Study GuideNikki Angela Lirio BercillaNo ratings yet

- Ethnomedicinal Plants of Hanumangarh DistrictDocument3 pagesEthnomedicinal Plants of Hanumangarh DistrictbharatNo ratings yet

- Chinese Herbs Listing - Chinese & English TranslationDocument6 pagesChinese Herbs Listing - Chinese & English Translationmelissa_tl_tanNo ratings yet

- Biology, ecology and management of invasive Tithonia diversifolia in ZimbabweDocument23 pagesBiology, ecology and management of invasive Tithonia diversifolia in ZimbabweBrighton GutuNo ratings yet

- Potato Tissue Culture Innovations For Asia PacificDocument54 pagesPotato Tissue Culture Innovations For Asia PacificRaymond KatabaziNo ratings yet

- Mahogany: A suitable timber species for agroforestryDocument9 pagesMahogany: A suitable timber species for agroforestrykarl koNo ratings yet

- Nutrient-Rich Avocado GuideDocument8 pagesNutrient-Rich Avocado GuideSper BacenaNo ratings yet

- OPDocument406 pagesOPLupita LoperenaNo ratings yet

- Supervised by Dr:zahraa Ibraheim Jawad ShubberDocument9 pagesSupervised by Dr:zahraa Ibraheim Jawad Shubberهاني عقيل حسين جوادNo ratings yet

- Peluang Budidaya Kurma TropisDocument23 pagesPeluang Budidaya Kurma TropisHenny PurwatiNo ratings yet

- Coffee EstablishmentDocument23 pagesCoffee EstablishmentAMERUDIN DIMALANASNo ratings yet

- Basal Area DBH DeterminationDocument2 pagesBasal Area DBH DeterminationInga Budadoy NaudadongNo ratings yet

- Grade 8 Plants Progress Test ReviewDocument16 pagesGrade 8 Plants Progress Test Reviewpixelhobo100% (1)

- Unit 11Document64 pagesUnit 11Lighto RyusakiNo ratings yet

- Research Biology 1Document18 pagesResearch Biology 1Nadjah OdalNo ratings yet

- Manual For Seed Potato Production Using Aeroponics PDFDocument268 pagesManual For Seed Potato Production Using Aeroponics PDFDario BaronaNo ratings yet

- Transpiration Biology Class X - ICSE (2019-20)Document22 pagesTranspiration Biology Class X - ICSE (2019-20)the lillyNo ratings yet

- Weed Book - 060824Document32 pagesWeed Book - 060824cliffordmsndNo ratings yet

- New Hot Spot 1 WB Module2 WM PDFDocument18 pagesNew Hot Spot 1 WB Module2 WM PDFMagda StręciwilkNo ratings yet

- NEP Syllabus B.Sc. BotanyDocument41 pagesNEP Syllabus B.Sc. Botany9C AKASH SNo ratings yet

- Natural Vegetation of IndiaDocument7 pagesNatural Vegetation of IndiaVarun ChaudharyNo ratings yet

- Evolution and Taxonomy of The Grasses (Poaceae) : A Model Family For The Study of Species-Rich GroupsDocument40 pagesEvolution and Taxonomy of The Grasses (Poaceae) : A Model Family For The Study of Species-Rich GroupsWillian MexNo ratings yet

- AvocadoDocument6 pagesAvocadoJake SagadNo ratings yet

- Pollination of AdromischusDocument2 pagesPollination of AdromischusveldfloraedNo ratings yet

- Major Use of Pesticides Insecticides PDFDocument82 pagesMajor Use of Pesticides Insecticides PDFAvijitSinharoyNo ratings yet

- Fitoremediasi Tanah Tercemar Logam Berat CD Menggunakan TANAMAN HANJUANG (Cordyline Fruticosa)Document9 pagesFitoremediasi Tanah Tercemar Logam Berat CD Menggunakan TANAMAN HANJUANG (Cordyline Fruticosa)Ayulian SaraNo ratings yet

- Double Fertilization - WikipediaDocument27 pagesDouble Fertilization - WikipediaBashiir NuurNo ratings yet

- Sexual Reproduction in Plants ExplainedDocument20 pagesSexual Reproduction in Plants Explainedsuresh muthuramanNo ratings yet

- Important Questions For CBSE Class 9 Science Chapter 6Document16 pagesImportant Questions For CBSE Class 9 Science Chapter 6VI A 19 Aaryan JadhavNo ratings yet

- Banana and Dragon FruitDocument26 pagesBanana and Dragon FruitNoreena Twinkle FajardoNo ratings yet