Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Racial Disparities Found in Pinpointing Mental Illness

Uploaded by

Teddy Million0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

34 views9 pagesRDFPMI

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentRDFPMI

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

34 views9 pagesRacial Disparities Found in Pinpointing Mental Illness

Uploaded by

Teddy MillionRDFPMI

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 9

Racial Disparities Found in Pinpointing Mental Illness

By Shankar Vedantam

Washington Post Staff Writer

Tuesday, June 28, 2005

Last of three articles

John Zeber recently examined one of the nation's largest

databases of psychiatric cases to evaluate how doctors diagnose

schizophrenia, a disorder that often portends years of powerful

brain-altering drugs, social ostracism and forced

hospitalizations.

Although schizophrenia has been shown to affect all ethnic

groups at the same rate, the scientist found that blacks in the

United States were more than four times as likely to be

diagnosed with the disorder as whites. Hispanics were more than

three times as likely to be diagnosed as whites.

Zeber, who studies quality, cost and access issues for the U.S.

Department of Veterans Affairs, found that differences in

wealth, drug addiction and other variables could not explain the

disparity in diagnoses: "The only factor that was truly important

was race."

The analysis of 134,523 mentally ill patients in a VA registry is

by far the largest national sample to show broad ethnic

disparities in the diagnosis of serious mental disorders in the

United States.

The data confirm the fears of experts who have warned for years

that minorities are more likely to be misdiagnosed as having

serious psychiatric problems. "Bias is a very real issue," said

Francis Lu, a psychiatrist at the University of California at San

Francisco. "We don't talk about it -- it's upsetting. We see

ourselves as unbiased and rational and scientific."

As the ranks of America's patients and doctors become more

diverse, psychiatrists such as Lu are spearheading a movement

to address the problem. Clinicians need to be trained in "cultural

competence," they say, to prevent misdiagnosis and harm.

Psychiatrist Heather Hall, a colleague of Lu's, said she had to

correct the diagnoses of about 40 minorities over a two-year

period. She estimated that one in 10 patients referred to her

came with a misdiagnosis such as schizophrenia, a disorder

characterized by social withdrawal, communication problems,

and psychotic symptoms such as delusions and hallucinations.

Unlike AIDS or cancer, mental illnesses cannot be diagnosed

with a brain scan or a blood test. The impressions of doctors --

drawn from verbal and nonverbal cues -- determine whether a

patient is healthy or sick.

"Because we have no lab test, the only way we can test if

someone is psychotic is, we use ourselves as the measure," said

Michael Smith, a psychiatrist at the University of California at

Los Angeles who studies the effects of culture and ethnicity on

psychiatry. "If it sounds unusual to us, we call it psychotic."

When hospitals diversified their staffs to include Spanish-

speaking doctors, many cases of psychotic behavior were

reassessed, he said: "Half the cases were rediagnosed as

depression. Some doctors think if you don't make eye contact,

you can be diagnosed. In some communities, eye contact is a

sign of disrespect."

Zeber and a team of other researchers said they do not know

why doctors were more likely to diagnose schizophrenia among

blacks and Hispanics. Perhaps diagnostic measures developed

primarily with white patients in mind do not automatically apply

to other groups, said Zeber, who published his results in the

journal Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology.

"Race appears to matter and still appears to adversely pervade

the clinical encounter, whether consciously or not," Zeber and

his colleagues wrote in their October 2004 report.

Darrel Regier, director of the division of research at the

American Psychiatric Association and U.S. editor of the journal,

said the study had been carefully conducted. He agreed that

cultural differences between patients and doctors could result in

misdiagnosis.

"I believe bias exists, and there is a risk a psychiatrist with a

different cultural experience than a patient can misinterpret the

expression of a psychiatric symptom," he said. "If you have a

very religious group of patients and a very secular psychiatrist

who thinks beliefs in spirits or hearing the voice of God is not

normal, you are going to have misses."

But he added that Zeber's study did not explain what caused the

diagnostic disparity among the veterans. Regier also questioned

whether the veterans in the study were representative of the

general population, or even representative of all veterans.

Different ethnic groups seek care in different ways within and

outside the VA, he said, and blacks tend to seek care when they

are sicker than white patients.

While agreeing that even more comprehensive analyses are

possible, Zeber stood by his findings. The study had carefully

eliminated a host of confounding variables, he said, and the

analysis had not found that black patients were any sicker than

whites. "Access issues or selection bias are unlikely to account

for our findings," the paper concluded.

"If you have an African American patient presenting with

elevated paranoia, that has been referred to in some quarters as

healthy paranoia based on how they perceive society," said

Zeber, who works at the Veterans Affairs Department's Health

Services Research and Development center in San Antonio. "If

you base your diagnosis on that symptom, you can be misled."

Zeber's argument is supported by a panel of academic experts

who helped draft a research agenda in 2002 for the next edition

of psychiatry's manual of mental disorders.

They wrote: "Misdiagnosis due to a different cultural

perspective of bizarreness is rather frequent." Inattention to the

role that social standards and cultural factors play in diagnosis

has caused patients to be stereotyped, they added, "with obvious

negative consequences for diagnosis and treatment."

Rethinking a Diagnosis

The patient was a young black man named Kevin Moore. He

had been picked up by police -- after his mother called 911 and

said he was making threats. The police brought him to San

Francisco General Hospital.

Moore already had a diagnosis from previous stints at other

hospitals: schizophrenia.

But psychiatrist Heather Hall thought something was wrong.

Patients with schizophrenia can seem to shrink into their own

world.

Superficially, Moore matched that description. He was

uncommunicative. But when Hall looked closer, she noticed

something else.

"A schizophrenic would be flat, he would be staring blankly into

space," Hall said in an interview about Moore's case, given with

his permission. "His expression wasn't moving, but he wasn't

blank. He looked really, really sad."

After a thorough evaluation, Hall changed Moore's diagnosis to

depression and reconfigured his medication regimen. She spent

hours with Moore, coaxing him to talk. Within weeks, he began

opening up about a host of interpersonal problems.

Moore said he was first diagnosed with schizophrenia when he

was 16 or 17. In an interview at the San Francisco hospital, he

was dressed in a baggy sweat shirt and sported his hair in

cornrows. His braces made him seem younger than his age -- 24

at the time.

He said the police had picked him up because he had talked of

getting a gun. A quarrel with a friend had escalated into a fight,

and his mother had called the police. Moore thought his mother

had overreacted, and he was sullen and uncommunicative when

the police forcibly took him to the hospital.

"I probably didn't want to talk to any people," he said. "I didn't

want to be there."

The particularly close attention that Hall paid to Moore was not

the only unusual thing about his treatment. Moore was treated at

one of the hospital's "focus units" -- inpatient psychiatric centers

that focus on how culture and ethnicity influence psychiatric

diagnosis and treatment.

The units pay attention to everything -- the decor as well as the

treatment: The Black Focus Unit, for example, had African and

African American art and icons on the walls. The occupational

therapy room had photos of Vanessa Williams, Maya Angelou

and Oprah Winfrey. The hospital also had an HIV-AIDS and a

Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Focus Unit, as well as

a Latino/Women's Focus Unit. The Asian Focus Unit had

bulletins printed in multiple Asian languages.

The specialized units have been hailed as an innovative way to

put patients at ease, but they have also faced criticism.

Psychiatrist Sally Satel described them as a type of "apartheid."

Satel, who is affiliated with the American Enterprise Institute

and is the author of "PC, M.D.: How Political Correctness Is

Corrupting Medicine," said such divisions can prompt patients

to avoid examining the real source of their mental problems.

"In its worst form, it is not really counseling," she said of what

she called multicultural therapy. "It is a support group between

two people who want to blame the outside world."

Moore and psychiatrist Hall are both black, but the hospital does

not match doctors and patients by ethnicity. Every unit had staff

members and patients from diverse backgrounds, and

psychiatrist Lu said the wishes of patients and special needs

such as language and prior history determined where patients

were assigned. Every unit had specialized training -- staff

members at the Asian Focus Unit, for example, spoke 14

languages.

Hall said Moore was a perfect example of why the Black Focus

Unit is important: "Maybe because I am an African American

psychiatrist, maybe he was able to show me a little more of

himself for me to make an accurate diagnosis and change his

treatment to a more accurate treatment."

She added, "Because the people who work on our unit are

sensitive to the issues of African Americans, we are much more

likely to look at our patients with eyes that aren't clouded by

preconceived notions."

The psychiatrist recalled another case of a black man diagnosed

as delusional. The man had talked about going to another city

and getting revenge on people who had killed his son.

"The treatment plan was filled out by someone who was not part

of our focus unit," she said. "She assumed it was a delusion --

she said, 'This man has a delusion that his son was killed in a

hate crime.' " Hall checked out the man's account. It turned out

to be true.

"People say minorities don't follow up" in psychiatric care, Hall

said. "Maybe on their first session they are not heard. Why

would they come back? If I tell a therapist I am being brutalized

and he thinks I am delusional, why would I come back?"

Other clinicians echo such views. UCLA's Smith, who speaks

Spanish, said that while making rounds with residents, he once

asked an interpreter to check whether a Spanish-speaking patient

wanted to commit suicide: "The patient said, 'I feel so bad I

could die.' " But rather than convey the sense that the patient

was in distress and felt terrible, Smith said, the interpreter told

the residents, "She's suicidal."

Carl Bell, a Chicago psychiatrist, said he once went through the

medical records of minority patients at Jackson Park Hospital in

Chicago and found many misdiagnoses. One 30-year-old woman

was talking fast, was calling people at all hours and did not seem

to need sleep -- classic symptoms of bipolar disorder, or manic-

depression. But her charts showed she had been hospitalized for

schizophrenia and treated with injectable medications, which

suggested that her doctors thought her schizophrenia was

particularly severe.

"How does a woman with a college education, a job . . . she has

euphoria, pressured speech, decreased need for sleep -- how do

you get schizophrenia, chronic schizophrenia?" asked Bell, still

incredulous.

Advocates for cultural competence say both clinicians and

patients are unwilling to acknowledge that race might matter:

"In a cross-cultural situation, race or ethnicity is the white

elephant in the room," said Lillian Comas-Diaz, a

psychotherapist in Washington, who added that she always

brings up the subject with patients as a way to get hidden issues

into the open -- and increase trust.

"I say, 'You happen to be Pakistani, and I am not -- how do you

feel about that?' Sometimes they say, 'Oh, it's not important,' but

when certain things happen [later] in therapy, people remember

you opened the door and they come inside," she said.

Tina Tong Yee, a psychologist in charge of ensuring San

Francisco's mental health services are culturally competent, said

Western medicine's secular notions of normality are sometimes

an uneasy fit in a deeply religious and increasingly diverse

America.

"Seeing ghosts in my family was part of growing up," she said.

"If I brought it up in therapy, you don't want someone to make

that delusional."

Behavioral problems are different than other kinds of ailments,

she added: "What you are reading is not a pulse, but how people

act and behave and how you react to it. In a cross-cultural

setting, it's ripe for misunderstanding."

You might also like

- Term PaperDocument7 pagesTerm Paperapi-533963418No ratings yet

- Black and Blue: The Origins and Consequences of Medical RacismFrom EverandBlack and Blue: The Origins and Consequences of Medical RacismRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (2)

- Schizophrenia Final PaperDocument6 pagesSchizophrenia Final Paperchad5844No ratings yet

- Outline and Evaluate the Classification and Diagnosis of SchizophreniaDocument1 pageOutline and Evaluate the Classification and Diagnosis of SchizophreniasophiabalkizovaNo ratings yet

- Allison - Final PaperDocument11 pagesAllison - Final Paperapi-262418945No ratings yet

- Mental IllnessDocument3 pagesMental IllnessQuezon City Science High SchoolNo ratings yet

- Racism and Psychiatry: Contemporary Issues and InterventionsFrom EverandRacism and Psychiatry: Contemporary Issues and InterventionsMorgan M. MedlockNo ratings yet

- Day 1 Intro RVDocument34 pagesDay 1 Intro RVapi-433532127No ratings yet

- Mental Health Case Study: Schizoaffective Disorder 1Document12 pagesMental Health Case Study: Schizoaffective Disorder 1api-402634520No ratings yet

- Szasz T. - The Lying Truths of PsychiatryDocument16 pagesSzasz T. - The Lying Truths of PsychiatryfoxtroutNo ratings yet

- Barrett Impulsiveness Scale (BIS-11)Document10 pagesBarrett Impulsiveness Scale (BIS-11)andr3yl0No ratings yet

- Psychiatric Mental Health Comprehensive Case StudyDocument12 pagesPsychiatric Mental Health Comprehensive Case Studyapi-508432180No ratings yet

- LIDZ THEODORE - A Psicosocial Orientation To Schizophrenic DisordersDocument9 pagesLIDZ THEODORE - A Psicosocial Orientation To Schizophrenic DisordersRodrigo G.No ratings yet

- Mind and CultureDocument18 pagesMind and CultureTeddy MillionNo ratings yet

- Schizophrenia FinalDocument9 pagesSchizophrenia Finalapi-285384246No ratings yet

- The Americanization of Mental IllnessDocument4 pagesThe Americanization of Mental Illnessfiona.tangNo ratings yet

- Final Annotated BibliographyDocument5 pagesFinal Annotated BibliographyRKeshiasmithNo ratings yet

- Issues Brief FinalDocument8 pagesIssues Brief Finalapi-253736544No ratings yet

- Rosenhan Experiment - WikipediaDocument10 pagesRosenhan Experiment - WikipediaLeonardo MoncadaNo ratings yet

- Ismresearchassessment 2Document10 pagesIsmresearchassessment 2api-339158068No ratings yet

- Epidemic in Mental Illness - Clinical Fact or Survey Artifact HorowitzDocument5 pagesEpidemic in Mental Illness - Clinical Fact or Survey Artifact Horowitzmariyaye.a23No ratings yet

- Student Name:: Impacts of Schizophrenia On Gender and Race 1Document4 pagesStudent Name:: Impacts of Schizophrenia On Gender and Race 1Paul WahomeNo ratings yet

- Schizophrenia and Violent Behavior.Document13 pagesSchizophrenia and Violent Behavior.Miguel MorenoNo ratings yet

- U07a1 Literature Evaluation PaperDocument11 pagesU07a1 Literature Evaluation Paperarhodes777100% (1)

- Case DigestDocument3 pagesCase DigestErika LapitanNo ratings yet

- Annelle B. Primm, M.D., M.P.H. Arlington, Va. Ezra E.H. Griffith, M.DDocument2 pagesAnnelle B. Primm, M.D., M.P.H. Arlington, Va. Ezra E.H. Griffith, M.DYuliana SariNo ratings yet

- Victims of Organized Stalking Delusional Schizophrenic or The Targets of Psychiatric PersecutionDocument8 pagesVictims of Organized Stalking Delusional Schizophrenic or The Targets of Psychiatric PersecutionSimon BenjaminNo ratings yet

- Mental Health 1CC3 Discussion QuestionsDocument2 pagesMental Health 1CC3 Discussion QuestionsSim100% (1)

- Sourceanalysis1 10Document19 pagesSourceanalysis1 10api-340469367No ratings yet

- Research About SchizophreniaDocument13 pagesResearch About SchizophreniaAbigailPascualMarcialNo ratings yet

- Conference 1 Team Prep Sheet RevisedDocument4 pagesConference 1 Team Prep Sheet Revisedapi-610733417No ratings yet

- Vahabzadeh 2011Document8 pagesVahabzadeh 2011Liridon1804No ratings yet

- Schizophrenia Revealed To Be 8 Genetically Distinct DisordersDocument3 pagesSchizophrenia Revealed To Be 8 Genetically Distinct DisordersNataliaNo ratings yet

- Victimology As A Branch of CriminologyDocument40 pagesVictimology As A Branch of CriminologySeagal UmarNo ratings yet

- Clinical Case HistoriesDocument3 pagesClinical Case HistoriesNazra NoorNo ratings yet

- How Mental Health Professionals Diagnose Patients: Rosenhan's Insightful StudyDocument6 pagesHow Mental Health Professionals Diagnose Patients: Rosenhan's Insightful Studyrameenfatima1No ratings yet

- 2011-Transgender and Gender Variant Populations With Mental Illness, Implication For Clinical PracticeDocument6 pages2011-Transgender and Gender Variant Populations With Mental Illness, Implication For Clinical PracticejuaromerNo ratings yet

- On Being Sane in Insane Places PDFDocument8 pagesOn Being Sane in Insane Places PDFEdirfNo ratings yet

- How Psychiatry Lost Its Way - McHugh 2010Document10 pagesHow Psychiatry Lost Its Way - McHugh 2010jmtalmadge100% (1)

- Our Failed Approach To SchizophreniaDocument3 pagesOur Failed Approach To SchizophreniaCharles AbelNo ratings yet

- Our Failed Approach To SchizophreniaDocument3 pagesOur Failed Approach To SchizophreniaCharles AbelNo ratings yet

- Warning: Psychiatry Can Be Hazardous to Your Mental HealthFrom EverandWarning: Psychiatry Can Be Hazardous to Your Mental HealthRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (6)

- The Great Pretender The Undercover Mission That Changed Our Understanding of Madness-201-356Document156 pagesThe Great Pretender The Undercover Mission That Changed Our Understanding of Madness-201-356M sNo ratings yet

- Annotated Bibliography For Black Doctor's IntersectionDocument5 pagesAnnotated Bibliography For Black Doctor's Intersectionjeremiah tawandaNo ratings yet

- Draft For Research Essay-4 CDocument12 pagesDraft For Research Essay-4 Capi-457704259No ratings yet

- Theres A Suicide Epidemic in Utah-PrintDocument13 pagesTheres A Suicide Epidemic in Utah-Printapi-259982879No ratings yet

- Seeing Patients: A Surgeon’s Story of Race and Medical Bias, With a New PrefaceFrom EverandSeeing Patients: A Surgeon’s Story of Race and Medical Bias, With a New PrefaceNo ratings yet

- 2010JAN08 The Americanization of Mental Illness - NYTimesDocument8 pages2010JAN08 The Americanization of Mental Illness - NYTimescrljones100% (1)

- Memoir Paper 2Document6 pagesMemoir Paper 2api-571168921No ratings yet

- Explaining Suicide: Patterns, Motivations, and What Notes RevealFrom EverandExplaining Suicide: Patterns, Motivations, and What Notes RevealNo ratings yet

- Pedophilia, Minor-Attracted Persons, and The DSMDocument12 pagesPedophilia, Minor-Attracted Persons, and The DSMCayoBuay100% (1)

- The Myth of Mental Illness: Foundations of a Theory of Personal ConductFrom EverandThe Myth of Mental Illness: Foundations of a Theory of Personal ConductRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (17)

- Case Study Mental HealthDocument11 pagesCase Study Mental Healthapi-402917163No ratings yet

- Psychiatry in The Age of AIDS: The Doctors See A New Chance To Be JailersDocument7 pagesPsychiatry in The Age of AIDS: The Doctors See A New Chance To Be JailersGeorge RoseNo ratings yet

- Psychology Project 2nd SemDocument19 pagesPsychology Project 2nd SemAkankshaNo ratings yet

- Abnormal Psychology Learning OutcomesDocument7 pagesAbnormal Psychology Learning OutcomesDeena MMoussalli DalalNo ratings yet

- DID Atau Biasa Disebut Gangguan Identitas DisosiatifDocument15 pagesDID Atau Biasa Disebut Gangguan Identitas DisosiatifCM Studio (cikndo)No ratings yet

- Critical Medical AnthropologyDocument11 pagesCritical Medical Anthropologyapi-254768363No ratings yet

- Article Homosexuality and Scientific Evidence: On Suspect Anecdotes, Antiquated Data, and Broad GeneralizationsDocument27 pagesArticle Homosexuality and Scientific Evidence: On Suspect Anecdotes, Antiquated Data, and Broad GeneralizationsPhạm Ngọc Hoàng MinhNo ratings yet

- Psychopathology of Racism PDFDocument15 pagesPsychopathology of Racism PDFLily EneNo ratings yet

- Policy AnalysisDocument6 pagesPolicy AnalysisTeddy MillionNo ratings yet

- Buscail - Laurie Original FileDocument2,236 pagesBuscail - Laurie Original FileTeddy MillionNo ratings yet

- Mind and CultureDocument18 pagesMind and CultureTeddy MillionNo ratings yet

- IPDC Presentation PDFDocument19 pagesIPDC Presentation PDFTeddy Million0% (1)

- Fikru DebeleDocument76 pagesFikru DebeleTeddy MillionNo ratings yet

- Mind and CultureDocument18 pagesMind and CultureTeddy MillionNo ratings yet

- Spanish Grammar PDFDocument180 pagesSpanish Grammar PDFChiều Biển VắngNo ratings yet

- Book Scan 03Document1 pageBook Scan 03Teddy MillionNo ratings yet

- Spanish Grammar and Words & PhrasesDocument85 pagesSpanish Grammar and Words & PhrasesXanh Va83% (6)

- Spanish Grammar and Words & PhrasesDocument85 pagesSpanish Grammar and Words & PhrasesXanh Va83% (6)

- Stakeholders Participation in Policy Analysis in Ethiopia PDFDocument28 pagesStakeholders Participation in Policy Analysis in Ethiopia PDFTeddy MillionNo ratings yet

- Medium ClinicDocument65 pagesMedium ClinicTeddy Million100% (1)

- Mamushet W.amanuelDocument86 pagesMamushet W.amanuelTeddy Million100% (3)

- Fikru DebeleDocument76 pagesFikru DebeleTeddy MillionNo ratings yet

- Medium ClinicDocument65 pagesMedium ClinicTeddy Million100% (1)

- Kidase PDFDocument170 pagesKidase PDFTeddy Million90% (21)

- ExamplesofLikertscales PDFDocument3 pagesExamplesofLikertscales PDFEdmund Earl Timothy Hular Burdeos IIINo ratings yet

- Basic Tutorial Stata PDFDocument5 pagesBasic Tutorial Stata PDFTeddy MillionNo ratings yet

- The SawDocument15 pagesThe SawTeddy MillionNo ratings yet

- 3D Animation: Type: Animation Gif Type: Animation Gif Type: Animation GifDocument4 pages3D Animation: Type: Animation Gif Type: Animation Gif Type: Animation GifTeddy MillionNo ratings yet

- Kidase PDFDocument170 pagesKidase PDFTeddy Million90% (21)

- Advanced Negotiation SkillsDocument5 pagesAdvanced Negotiation SkillsTeddy MillionNo ratings yet

- Motivators Guide BookDocument9 pagesMotivators Guide Book44abcNo ratings yet

- Preparing For The IELTS Test With Holmesglen Institute of TAFEDocument9 pagesPreparing For The IELTS Test With Holmesglen Institute of TAFEhanikaruNo ratings yet

- Guide To Understanding Financial Statements PDFDocument96 pagesGuide To Understanding Financial Statements PDFyarokNo ratings yet

- Wurs AdhdDocument4 pagesWurs AdhdR ZnttNo ratings yet

- PSYCH - Psych Emegencies 3rdDocument42 pagesPSYCH - Psych Emegencies 3rdapi-38560510% (1)

- Psychiatric Nursing ReviewDocument16 pagesPsychiatric Nursing Reviewɹǝʍdןnos97% (63)

- Schizophrenia Lesson PlanDocument1 pageSchizophrenia Lesson Planapi-294223737No ratings yet

- Case Study PP - AdhdDocument21 pagesCase Study PP - Adhdapi-482726932100% (1)

- Autistic Self Advocacy Network With Autism NOW May 28, 2013Document21 pagesAutistic Self Advocacy Network With Autism NOW May 28, 2013The Autism NOW CenterNo ratings yet

- Aileen Wuornos Criminal DisorderDocument7 pagesAileen Wuornos Criminal DisorderDaniel Gitau100% (1)

- Pre-Test Psychiatric NursingDocument17 pagesPre-Test Psychiatric NursingDefensor Pison Gringgo100% (1)

- Adult Patients With AdhdDocument4 pagesAdult Patients With AdhdLaura FrekiNo ratings yet

- Baby Blues: By: Julien Jimenez, MDDocument9 pagesBaby Blues: By: Julien Jimenez, MDjulien jNo ratings yet

- Aldao, Nolen-Hoeksema, & Schweizer, 2010 PDFDocument22 pagesAldao, Nolen-Hoeksema, & Schweizer, 2010 PDFAna Sofia AlmeidaNo ratings yet

- Psychotherapy Progress Note: Intervention(s) UsedDocument1 pagePsychotherapy Progress Note: Intervention(s) UsedPaola Buffit TorresNo ratings yet

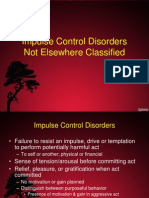

- Impulse Control DisordersDocument97 pagesImpulse Control DisordersGanpat VankarNo ratings yet

- Read The Following Text Written by Jacquie Mccarnan and Answer The Questions On The RightDocument1 pageRead The Following Text Written by Jacquie Mccarnan and Answer The Questions On The RightDiana GarcíaNo ratings yet

- Excerpt from the book "Saving Normal: An Insider's Revolt Against Out-of-Control Psychiatric Diagnosis, DSM-5, Big Pharma, and the Medicalization of Ordinary Life" by Allen Frances. Published by William Morrow. Copyright © 2013 by Allen Frances. Reprinted with permission.Document10 pagesExcerpt from the book "Saving Normal: An Insider's Revolt Against Out-of-Control Psychiatric Diagnosis, DSM-5, Big Pharma, and the Medicalization of Ordinary Life" by Allen Frances. Published by William Morrow. Copyright © 2013 by Allen Frances. Reprinted with permission.wamu8850100% (1)

- Colegio Cenacap Worksheet on Eating DisordersDocument3 pagesColegio Cenacap Worksheet on Eating DisordersSERGIO ReinaNo ratings yet

- Paraphilic Disorders Fact SheetDocument2 pagesParaphilic Disorders Fact Sheetaloysius_ascentioNo ratings yet

- NSTP - Worksheet 1Document2 pagesNSTP - Worksheet 1Monique BalteNo ratings yet

- PhobiaDocument14 pagesPhobiaHemashree KogilavananNo ratings yet

- English Literature Review 1Document5 pagesEnglish Literature Review 1api-549248857No ratings yet

- Presentation For Music Therapy CourseDocument13 pagesPresentation For Music Therapy CourseRodney HarrisNo ratings yet

- What is Impulsivity and Its NeurobiologyDocument42 pagesWhat is Impulsivity and Its Neurobiologyfreebooks201350% (2)

- SCHIZOPHRENIA: A Clinical Syndrome of Variable PsychopathologyDocument7 pagesSCHIZOPHRENIA: A Clinical Syndrome of Variable PsychopathologyNica Lopez FernandezNo ratings yet

- History of DepressionDocument7 pagesHistory of Depressionklysmanu93No ratings yet

- Personality Disorders - Narcissism - Borderline - CodependenceDocument138 pagesPersonality Disorders - Narcissism - Borderline - CodependenceDean Amory100% (1)

- Writing Assignment #1Document2 pagesWriting Assignment #1Nallely Alvarez DiazNo ratings yet

- Postpartum Depression: Continuing Education ActivityDocument13 pagesPostpartum Depression: Continuing Education ActivityRatna Dewi100% (1)

- Chapter 13 Trauma and Stress-Related DisordersDocument7 pagesChapter 13 Trauma and Stress-Related DisordersCatia FernandesNo ratings yet

- No 13 Muhammad Saufi 17 Dec 2021 Elc 231 RT WedDocument11 pagesNo 13 Muhammad Saufi 17 Dec 2021 Elc 231 RT WedMuhd SaufiNo ratings yet