Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Content Server

Uploaded by

ararapiaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Content Server

Uploaded by

ararapiaCopyright:

Available Formats

Albuterol multidose dry powder inhaler efficacy and safety

versus placebo in children with asthma

Craig LaForce, M.D., C.P.I. , 1 Herminia Taveras, Ph.D., M.P.H .,2 Harald Iverson, Ph.D .,3

and Paul Shore, M.D., M.S.4

ABSTRACT

Background: A novel, inhalation-driven, multidose dry powder inhaler (MDPI) that does not require coordination of

actuation with inhalation has been developed.

Objective: To evaluate the efficacy and safety of albuterol M DPI versus placebo M DPI after chronic dosing in children with

asthma.

Methods: This phase III, double-blind, parallel-group study included children with asthma (ages, 4-11 years) with forced

expiratory volume in 1 second (FEVj) of 50-95% of predicted. After a 14-day run-in period wherein the patients continued

their current asthma therapy and received single-blind placebo MDPI, they were randomized to albuterol M DPI 90 peg per

inhalation, two inhalations four times daily (total daily dose, 720 p,g), or placebo for 3 weeks. Pulmonary function was assessed

on days 1 and 22. Efficacy and safety were evaluated by measuring the baseline-adjusted percent-predicted FEV1 (PPFEV f area

under the time curve over 6 hours (AUC0_6) after the dose and adverse events, respectively.

Results: The full analysis set included 184 patients. Patients treated with albuterol M DPI versus patients treated with

placebo MDPI had significantly greater baseline-adjusted PPFEV, AU C 0_6 over 3 weeks (least squares mean difference,

25.0% •hour, which favored albuterol; p < 0.001). The benefit of albuterol (mean change in PPFEVj) was evident 5 minutes

after dosing and lasted several hours; the maximal effect was noted 1 to 2 hours after dosing. Albuterol M DPI was well

tolerated.

Conclusions: In children with persistent asthma, albuterol M DPI improved pulmonary function significantly better than

placebo M DPI over 3 weeks of treatment. Clinical efficacy was evident within 5 minutes of dosing and maintained for >2 hours.

Four times daily administration was well tolerated.

(Allergy Asthma Proc 38:28-37, 2017; doi: 10.2500/aap.2017.38.4015)

hort-acting /32-adrenergic agonists (e.g., albuterol) some evidence that long-term use of short-acting /32-

S promptly reverse acute airflow obstruction and

relieve bronchoconstriction and accompanying acute

adrenergic agonists may lead to tachyphylaxis and

increased asthma exacerbations.4,5 Albuterol has tradi

asthma symptoms, such as cough, chest tightness, tionally been delivered via a metered-dose inhaler

shortness of breath, and wheezing.1 Studies of long (MDI) in an aerosolized form or a nebulized formula

term albuterol use in patients with asthma have not tion. Proper use of the MDI requires that patients co

identified any safety concerns2,3; however, there is ordinate device actuation with inhalation; usage errors

with the MDI are common, especially among children.6

Incorrect inhaler technique can compromise drug deliv

From the 1North Carolina Clinical Research, Raleigh, North Carolina, 2Clinical

Research and Development, Teva Pharmaceuticals, Miami, Florida, 3Statistics De

ery to the distal lung and result in poor control of asthma

partment, Teva Pharmaceuticals, Miami, Florida, and 4Clinical Research and Devel symptoms.6 Devices that use breath actuation reduce ad

opment, Teva Pharmaceuticals, Frazer, Pennsylvania ministration errors compared with conventional MDIs.7

This study was sponsored by Teva Branded Pharmaceutical Products R&D, Inc.

Medical writing assistance was provided by Lisa Feder, Ph.D., Peloton Advantage, and

A novel, inhalation-driven, multidose dry powder

was funded by Teva Branded Pharmaceutical Products R&D, Inc. Teva provided a fu ll inhaler (MDPI) (ProAir RespiClick, Teva Pharmaceuti

review o f the article cals, Inc., Frazer, PA) that does not require patient

H. Taveras and H. Iverson are employees of Teva Pharmaceuticals. P. Shore was an

employee o f Teva Pharmaceuticals at the time of manuscript preparation. C. LaForce coordination of device actuation with inhalation was

has no conflicts o f interest pertaining to this article developed with the goal of reducing administration

Poster presentation at the American Academy o f Allergy, Asthma & Immunology

errors associated with conventional MDIs. In a recent

annual scientific meeting, Los Angeles, California, March 4 -7 , 2016, poster form at at

the Eastern Allergy Conference, Palm Beach, Florida, June 2-5, 2016, and poster open-label study, the use of this device was demon

form at (part o f the data) at the American Thoracic Society International Conference, strated to be well received in a study population that

San Francisco, California, M ay 13-18, 2016

included patients ^ 4 years of age and with asthma or

Address correspondence to Craig LaForce, M .D ., North Carolina Clinical Research,

2615 Lake Drive, Suite 301, Raleigh, N C 27607 chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: 83% of the pa

E-mail address: claforce@nccr.com tients reported being somewhat to very satisfied with

Published online November 28, 2016

Copyright © 2017, OceanSide Publications, Inc., U.S.A.

the MDPI with an integrated dose counter, 92% were

satisfied with the ease of holding and handling the

28 January-February 2017, Vol. 38, No. 1

Double-blind Treatm ent Period

Figure 1. Study design. MDP1 = Multidose dry powder inhaler; TD = treatment day.

inhaler, and 85% were satisfied with the ease of learn conducted in full accordance with the International

ing to use the inhaler.8 The safety and efficacy of albu Council for Harmonisation Good Clinical Practice

terol MDPI in adolescents and adults have been shown Guidelines. Parents or guardians of all enrolled pa

to be comparable with those of an available albuterol tients provided written, informed consent before all

hydrofluoroalkane (HFA) inhaler (ProAir HFA Inhala study-related procedures, and assent from the patients

tion Aerosol; Teva Respiratory LLC). themselves was obtained when applicable.

Albuterol MDPI received U.S. Food and Drug Ad

ministration approval in March 2015 for the treatment

Patients

or prevention of bronchospasm in patients ages 5:12

Patients who met the following criteria were eligible

years with reversible obstructive airway disease and

for the prevention of exercise-induced bronchospasm for inclusion in the study: boys or premenarchal girls

in patients ages >12 years.9 Albuterol MDPI demon ages 4 to 11 years (inclusive) with a documented diag

nosis of asthma for >6 months' duration that had been

strated safety comparable with that of a placebo MDPI

in an integrated safety analysis of phase III studies of stable for >4 weeks before the screening visit and on

patients ages ^12 years and with persistent asthma10 low-dose inhaled corticosteroids (<200 pg fluticasone

propionate per day or equivalent), leukotriene modifi

as well as efficacy, safety, pharmacokinetic, and phar

macodynamic profiles comparable with those of albu ers, inhaled cromones, or j82-agonists alone, as needed,

terol HFA in studies of adults and children ages >12 for >4 weeks before the screening visit; forced expira

years.11 A recent study demonstrated similar pharma tory volume in 1 second (FEV]) 50-95% of predicted

cokinetic and pharmacodynamic profiles for albuterol for age, height, and sex after >6 hours without /32-

MDPI and albuterol HFA in children 4-11 years of agonist use; a demonstrated prealbuterol predicted

age.12 The present study was designed to evaluate the FEVi value of >50% at all screening visits; demon

chronic-dose efficacy and safety of albuterol MDPI rel strated reversible bronchoconstriction, verified by a

ative to placebo in pediatric patients with asthma. >15% increase in FEVj within 30 minutes after 180 /rg

albuterol inhalation; and ability to self-perform peak

expiratory flow (PEF) measurements with a handheld

METHODS

peak flow meter. The patients were required to use the

Study Description and Ethics MDPI device correctly, either alone or with assistance

This was an 8-week (3-week treatment exposure), ran from a parent or guardian. Patients with a known

domized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase III trial sensitivity to albuterol or any of its formulation excipi

in children (ages 4-11 years) with asthma conducted at ents, a history of respiratory tract infection or disorder

49 centers across the United States (www.ClinicalTrials. that was not resolved within 4 weeks before the screen

gov identifier: NCT02126839; ABS-AS-303) from June ing visit, an asthma exacerbation that required oral

10, 2014, through February 11, 2015. The study con corticosteroids within 3 months or hospitalization

sisted of a screening period (1-9 days), a 2-week, sin within 6 months of the screening visit, or a history of

gle-blind run-in period, and a 3-week, double-blind life-threatening asthma were ineligible to participate.

treatment period (treatment day [TD] 1 to 22). The final Also excluded were patients who used prohibited con

treatment visit occurred on day 22, with a telephone comitant medications, were treated with oral or inject

call follow-up 3 to 5 days later (Fig. 1). Independent able corticosteroids within 6 weeks of the screening

ethics committees or institutional review boards at visit, or participated in a previous albuterol MDPI trial

each trial center approved the study protocol in accor at any time or received any investigational drug as part

dance with local or national regulations. The trial was of a trial within 30 days of the screening visit.

Allergy and Asthma Proceedings 29

Randomization occurred at the first treatment visit. 120, 240, and 360 minutes after baseline FEV1 assess

Patients were allowed to continue in the study if they ment and completion of study drug administration at

remained in general good health, had not experienced TDs 1 and 22. The primary efficacy end point was the

an adverse event (AE) that would result in failure to baseline-adjusted percent-predicted FEV1 (PPFEVj)

continue to meet selection criteria, had not used any area under the effect-time curve from time 0 (predose)

prohibited concomitant medications, had not taken to 6 hours (AUC0_6) after dosing over the 3-week treat

any rescue albuterol for >6 hours before each treat ment period. The secondary efficacy end point was the

ment visit, continued to demonstrate correct use of the baseline-adjusted postdose PEF AUC0_6 over the

MDP1 device, and had not had an asthma exacerbation 3-week treatment period. Additional efficacy end

or upper respiratory tract infection or received addi points included the maximum percentage change from

tional treatment for asthma other than rescue albuterol. baseline in FEV, and PEF observed up to 2 hours after

Patients' average predose FEVt values at treatment completion of dosing over the 3-week treatment period

visits could not exceed ±20% of the screening visit and at TDs 1 and 22; baseline-adjusted PPFEVj AUC0_6

value, and each predose interval was to remain 50- and PEF AUC0_6 at TDs 1 and 22; time to maximum

95% of the predicted value. FEVj and PEF at TDs 1 and 22; time, in minutes, to a

—15% and a >12% increase in baseline FEV, and PEF

Study D esign in patients who met this increase within 30 minutes

After an initial screening visit (1-9 days), eligible after dosing on TDs 1 and 22; duration, in hours, of an

patients entered the single-blind 2-week run-in period, increase of ^15% or ^12% above baseline within 6

during which they continued to use their current hours after dosing in patients who responded within

asthma therapy and received single-blind placebo 30 minutes on TDs 1 and 22; and the absolute and

MDPI and an albuterol HFA MDI (ProAir HFA; Teva) relative numbers of patients with a 12% and 15% in

to use as needed for the relief of acute asthma symp crease in baseline FEV, and PEF within 30 minutes

toms. At treatment visit 1, the patients were random after dosing on TDs 1 and 22.

ized (1:1 ratio) to receive albuterol MDPI 90 /xg per The patients received a paper diary during the run-in

inhalation or placebo MDPI as two inhalations (180 and treatment periods, and were required to make

Mg/dose) four times daily (~7 A.M., 12 noon, 5 P.M., daily entries throughout the study. Compliance with

and bedtime; a total daily dose of 720 /xg) for 3 weeks. diary entries was assessed during the run-in period.

The patients maintained their current asthma therapy Daily diary end points included changes from baseline

throughout the study; however, dosing with these con in the percentage of symptom-free days, rescue medi

current medications was withheld the morning of each cation-free 24-hour periods, and evenings without

treatment-evaluation visit and was delayed until the asthma-related awakenings. Other diary variables in

end of the study visit. The assigned treatments were cluded changes in daily (A.M.) predose PEF and in the

defined by a randomization code number assigned number of asthma-related nocturnal awakenings per

through an interactive voice response system/interac week, puffs of rescue medication per 24-hour period,

tive Web response system. Only one randomization list and puffs of rescue medication per evening. Asthma

was generated. Eligible patients were assigned the next symptoms, including wheezing, shortness of breath,

available randomization number according to a cen cough, and chest tightness, were recorded at the end of

trally generated randomization list. The patients and each day. The six-point Asthma Symptom Score (0, no

investigators remained blinded to the randomized symptoms during the day; 5, symptoms severe enough

treatment assignments during the study. The sponsor's to interfere with normal daily activities) was recorded

clinical personnel also were blinded to study drug daily. Changes from baseline to TD 21 were evaluated.

identity after the single-blind, run-in period until the

data base was locked for analysis and the treatment

A ssessm ent of Safety and Tolerability

assignments were revealed.

AEs were monitored throughout the trial and were

defined as any untoward medical occurrence (e.g.,

A ssessm ent of Efficacy physical sign, symptom, or laboratory parameter) or

Determinations of FEVj values were made by using medical condition that developed or worsened in se

standardized spirometers. Predicted FEVj values were verity, regardless of its relationship to the study drug.

computed and adjusted for age, height, and sex for Serious AEs included death, a life-threatening event,

patients ages 4-5 years13 and for patients ages 6-11 hospitalization or prolongation of hospitalization, per

years14 by using American Thoracic Society/European sistent or significant disability, congenital anomaly or

Respiratory Society criteria applicable to pediatric pa birth defect, or any event that jeopardized the patient

tients.15 Serial FEVj measurements (the highest of three and required medical intervention to prevent one of

acceptable maneuvers) were obtained 5, 15, 30, 45, 60, the aforementioned outcomes. Physical examinations,

30 January-February 2017, Vol. 38, No. 1

vital signs, and electrocardiograms were conducted on study. Of the 166 patients who were screened but not

TDs 1 and 22. An asthma exacerbation was defined as enrolled, 136 did not meet inclusion criteria. Of these

any worsening of asthma that required treatment other 136 patients, 77 (56.6%) did not meet reversibility cri

than rescue albuterol and/or regular inhaled cortico teria and 22 (16.2%) were unable to perform reproduc

steroid use, including the use of systemic corticoste ible spirometry. Twenty-five patients were enrolled

roids and / or an emergency department visit or hospi but not randomized for various reasons (Fig. 2). A total

talization that resulted in a change in the patient's of 186 patients were randomized (intent-to-treat pop

regular inhaled corticosteroid dose or the addition of ulation): 92 to the placebo MDPI group and 94 to the

other asthma medications. An exacerbation was not albuterol MDPI group. The safety population consisted

considered an AE unless it met the criteria for a serious of 185 patients; the full analysis set consisted of 184

AE. A patient who experienced an exacerbation was patients. Ten and 14 patients withdrew from the study

not discontinued from the trial unless the event met in the placebo MDPI and albuterol MDPI groups, re

serious AE criteria or the investigator believed that it spectively (Fig. 2). In general, baseline demographics

was in the patient's best interest to withdraw from the and clinical characteristics were similar between the

study. treatment groups. The most common comorbidities

were allergic rhinitis, eczema, and seasonal allergies.

Statistical Analyses Nearly every patient had taken previous medications

By using data from previous, similarly designed for obstructive airway disease, more than half had

studies in children with asthma, it was determined that taken systemic antihistamines, and nearly a fourth had

a sample size of 80 patients per treatment group would taken nasal preparations (Table 1).

have 90% power to detect a difference of ^11.0%‘ hour

(residual standard deviation, 23.7%»hour) at both TD 1

Efficacy

and TD 22 in baseline-adjusted PPFEV1 AUC0_6. When

assuming a 10% dropout rate, this number was in Over the 3-week treatment period, the patients who

creased to 90 patients per treatment group. All efficacy were treated with albuterol MDPI experienced signifi

analyses were performed on the full analysis set, de cant improvements in pulmonary function; the LS

fined as all randomized patients who received one or mean difference in baseline-adjusted PPFFV, AUC0_6

more doses of the study drug and had one or more (primary efficacy variable) was 25.0%»hour in favor of

postbaseline assessments. All safety assessments were albuterol MDPI versus placebo MDPI (95% confidence

performed on the safety population, which included all interval, 16.1-33.9; p < 0.001). Results by treatment group

randomized patients who took one or more doses of are summarized in Table 2. On TDs 1 and 22, the patients

the study drug. Patient demographic data were sum who received albuterol MDPI had significantly greater

marized descriptively. A mixed-model, repeated-mea baseline-adjusted PPFEVj AUC0_6 compared with pa

sures analysis was used to evaluate efficacy end points tients who received placebo MDPI (p < 0.001) (Table 3).

derived from spirometry measurements on study days Likewise, over 3 weeks of treatment, the patients who

1 and 22. Treatment group, study day, and their inter were treated with albuterol MDPI experienced a signifi

action were analyzed as fixed effects with the visit- cant improvement in baseline-adjusted PEF AUC0_6

specific baseline value as a covariate. An unstructured compared with those who received placebo MDPI; the LS

covariance matrix between repeated measures was as mean difference was 76.3 L/min»hour in favor of albu

sumed. Treatment-group least squares (LS) means and terol MDPI versus placebo MDPI (95% confidence inter

their corresponding 95% confidence intervals were val, 47.8-104.9; p < 0.001). Results by treatment group

used to calculate between-group differences. A similar and by TD are summarized in Tables 2 and 3, respec

model was used to evaluate weekly averages of daily tively. Similarly, improvements in baseline-adjusted

diary data at each study week. Percentage changes PEF AUCg_6 on TDs 1 and 22 also favored albuterol

from baseline in selected diary measures over the treat MDPI versus placebo MDPI (Table 3). Overall, for

ment period were analyzed with an analysis of cova FEVj and PEF, the median durations of the 12% and

riance model with the baseline weekly average as the 15% response rates on TDs 1 and 22 ranged from ~1 to

covariate. There was a single primary and secondary 4 hours (Table 4).

variable; additional analyses were not adjusted for The maximum percentage change from baseline in

multiplicity. FEVj and PEF within 2 hours of dosing was signifi

cantly greater in patients treated with albuterol MDPI

RESULTS compared with those who received placebo over the

3-week treatment period, on TD 1, and on TD 22 (p <

Patient Disposition and Baseline Characteristics 0.001) (Tables 2 and 3). The numbers and percentages

A total of 377 patients were screened at 49 centers in of patients who responded with a 12% or a 15% in

the United States, and 211 patients were enrolled in the crease in FEV-lor PEF from baseline within 30 minutes

Allergy and Asthma Proceedings 31

Patients screened

(N=377)

Screened but not enrolled 166

Inclusion criteria not met 136

Consent withdrawn Enrolled, not randomized 25

13

Lost to follow-up 7 Randomization criteria not met 14

Exclusion criteria met 4 Adverse event 4

Noncompliance 1 Consent withdrawn 4

Other 3

Other 5

Patients randomized

(n=186)

Placebo MDPI (n=92) Albuterol MDPI (n=94)

Safety population (n=92) Safety population (n=93)

Full analysis set (n=92) Full analysis set(n=92)

1

! W ithdrawn 10 1 1

1 Withdrawn 14 ;

i Consent withdrawn 2 1 1

Adverse event 1 1

| Protocol violation 2 1^ 1

Protocol violation 3 !

j Lost to follow-up 1 1 "l

Lost to follow-up 4 !

j Other 5 1 1 Sponsor request i !

1

1 1 Other 5 ;

1 1

Patients completed Patients completed

(n=82) (n=80)

Figure 2. Patient flow. MDPI Multidose dry poivder inhaler.

after dosing were significantly (p < 0.001) higher in the ical differences favored patients treated with albuterol.

albuterol MDPI group compared with the placebo Likewise, there were no significant between-treatment-

group for all measures (Table 3). The time to the onset group differences in LS mean change from baseline to

and duration of the 12% and the 15% response levels TD 21 for the daytime Asthma Symptom Score, asth

are summarized in Table 4. On TD 1, the median times ma-related nocturnal awakenings per week, morning

to 12% and 15% response onsets in FEV-l were just predose PEF, puffs of rescue medication per 24 hours,

under 6 minutes. On TD 22, the median time to 12% and puffs of rescue medication per evening.

response onset in FEV, was shorter than that for the

15% response onset. On TD 1, median times to the 12%

and the 15% response onset in PEF were just >5 min Safety and Tolerability

utes, and, on TD 22, the median time to 12% response During the 3-week treatment period, 23% of the pa

onset was shorter than that for the 15% response onset. tients in each treatment group experienced AEs, with a

The results from the daily diaries are summarized in low overall incidence (<4%). The most frequently oc

Table 5. Overall, there were no significant between- curring AE in both treatment groups was headache. In

treatment-group differences in changes from baseline the placebo MDPI group, other commonly reported

to TD 21 in the percentage of symptom-free days, AEs included pyrexia, upper abdominal pain, cough,

rescue medication-free 24-hour periods, or nights upper respiratory tract infection, and ligament sprain.

without asthma-related awakenings; however, numer In the albuterol MDPI group, cough and vomiting

32 January-February 2017, Vol. 38, No. 1

Table 1 Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of randomized patients

Characteristic Placebo MDPI Group Albuterol MDPI Group

(n = 92) (n = 94)

Age, m ean ± SD (range), y 8.5 ± 1.8 (4-11) 8.3 ± 1.7 (4-11)

Age group, no. (%)

4-7 y 23 (25.0) 30 (31.9)

8-11 y 69 (75.0) 64 (68.1)

Boys, no. (%) 55 (59.8) 52 (55.3)

Race, no. (%)

White 41 (44.6) 40 (42.6)

Black 48 (52.2) 52 (55.3)

Other 3 (3.3) 2(2.1)

Ethnicity, Flispanic/Latino, no. (%) 11 (12.0) 14 (14.9)

Body mass index, mean ± SD, k g /m 2 19.5 ± 5.0 19.4 ± 5.3

FEVl7 mean ± SD, L 1.7 ± 0.4 1.6 ± 0.4

PPFEVJ, mean ± SD, % 87.5 ± 11.5 89.0 ± 12.4

Airway reversibility, mean ± SD, % 22.0 ± 8.1 22.9 ± 8.2

Comorbid conditions of >10%, no. (%)

Allergic rhinitis 52 (56.5) 41 (43.6)

Eczema 22 (23.9) 31 (33.0)

Seasonal allergy 24 (26.1) 28 (29.8)

Perennial rhinitis 17(18.5) 23 (24.5)

Food allergy 16 (17.4) 14 (14.9)

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder 17(18.5) 9 (9.6)

Headache 13 (14.1) 7 (7.4)

Previous medications of ^20%, no. (%)

Drugs for obstructive airway disease 92 (100) 93 (98.9)

Systemic antihistamines 53 (57.6) 59 (62.8)

Nasal preparations 22 (23.9) 22 (23.4)

M D PI = Multidose dry powder inhaler; SD = standard deviation; FEV1 = forced expiratory volume in 1 s; PPFEV\ =

percent-predicted forced expiratory volume in 1 s.

Table 2 Results for the primary and additional key efficacy end points during the 3-week treatment period,

full analysis set

Variable (LS mean) Placebo MDPI Albuterol MDPI p

Group (n — 92) Group (n = 92)

Baseline-adjusted PPFEV! AUC0_6, %• hr 18.71 43.73 <0.001

Maximum percentage change from baseline in FEVj 10.39 20.00 <0.001

observed < 2 hr after completion of dosing

Baseline-adjusted PEF AUC0_6, L / m in • h r 71.52 147.85 <0.001

Maximum percentage change from baseline in PEF 13.84 25.57 <0.001

observed < 2 hr after completion of dosing

LS = Least squares; M DPI = multidose dry powder inhaler; PPFEV\ = percent-predicted forced expiratory volume in 1 s;

AU C 0_6 = area under the effect-time curve from time 0 (predose) to 6 hr (postdose); FEV-, = forced expiratory volume in 1 s;

PEF = peak expiratory flozv (rate).

were commonly reported (Table 6). There were no experienced an asthma exacerbation; all nine cases

deaths, serious AEs, or withdrawals due to AEs, and were moderate in severity. Eight patients recovered or

none of the reported AEs was deemed to be related to were recovering, and one patient on placebo MDPI had

the study drug. Four patients in the placebo MDPI not recovered. No patient with an asthma exacerbation

group and five patients in the albuterol MDPI group was discontinued from the study; however, five pa-

Allergy and Asthma Proceedings 33

=H= c—iH \—I rH rH r -H t- H O

OS o o o o o O O

r-H

o

o o p o o O o O 1>

Sp.3 o o o

03 o o d d d

> V V V V V V V

O

Cp h

<N

D S

<N S ii

X) S' ltT NO CN p LT?

T—I 00 LO oi r-H r -H CN

n u w (N o< NO LO d co NO^

D & o. H

CN (N c o C N

+* 3 3 LO

r-H IX o

LO LO

a

a s

6 < u

-4 -*

sieT,

'

ri

11 D

u -X

H

D 00

^ o co' <N On is

CO (N 00 oi ON LO LO K

o 3 rH rH GO CO <N 3

CO d N—' CN o

'S Dh L NO ri

H

rO

H O

rH <N

CN

CO

g g

Jh

u CO

|

rH r—I rH rH r-H rH rH rH o

o o o o O O o o u

p o o o O O o o is

d d d d d d d d

> V V V V V V V V CD

2 .

HH S

o

n-J O

C ^n •S

^^ ^^ CO

01 (N co LO CN rH IX LO 2 o

CD

CO rH oo oi CN O CO oo p

n o NO LO CO

(/) »-( 3 LO d

CN '^ LO

NO

00

CM ^^ 3 o

p Pu

>> - & CO 00 rH IX CO R

G NO IX NO 5^

g 01 £3 25 .2 ^

£ < O 2 §

Results for additional efficacy end points by treatment day, full

0) U ^

8 11

ph

Q

00 2 £h

s 00

O LO

On

CN IX rH p CO ON

0 On O ci r—'

vH co <N

x> d L O ■S M

01 rH NO 00 rH IX

CN rH C\|

g I B

> Ph g

w W 1> o „*

Data are least squares means unless otherwise indicated.

£P 6 Ph

6 pp 5 .*a

o o PS <D

co co o o II -h 3

g CO CO

11 QJ

.s

• I—I

X Sh Jh .s g P p> y

£, "as & 3 pj -q §

CO 60 Pp Ju H_

• O (B PP ^ «

c£ X> -Q .g

^ s

> > 't o PP Ph

W

w O W W II "a

Ph j p 13 PP Ph

r? 2H

PJ H- I

|D cu A <u ■

#Based on the least squares means.

0) §

Xl < g? CD

u°r

03 03 03

‘u 0 1) 11

>*

m -§

u u C u - J

< -§ u

h

U o o

CD

> PP 0) £ PP 0) \ a £ SX. 13 cs

CP, 60 P-l 60 v

^CD , sx

^

Ph JS Ph JS 13 o-

LH

O pH 11 c\| -a a- ^

r 13

> 1-* r*~

d 8

■4—> 03 0) b 03 CD 2 -X

CD

.£ <N 2 S3 CD -

§ s

, V| £ P3 Oh -9 3 X! 5

-x 2

13 "d

P "d '% 7 s

11 a <>

v ^

CD CD 0) 3 .£ CD CD s O 5 o

g £ dC ■c£ e b ^ e \£ a g w. g w

ai . D <X

3

% CD 0 ) ii . CD s-»

XI 33 •43 O .j ‘JG o •X o ~ O

Table

« § O 03 as C 1 « P i 03 £ 03 £ &3 •§

» s CP Ph cS s Ph pp Q

5

34 January-February 2017, Vol. 38, No. 1

Table 4 Summary statistics for response onset and duration after albuterol MDPI by treatment day, full

analysis set

Treatment Day 1 Treatment Day 22

FEY, PEF FEVj PEF

Time to 12% response onset

No. patients* 63 77 52 57

Mean ± SD, min 11.5 ± 9.8 10.3 ± 9.2 11.1 ± 8.5 10.6 ± 8.5

Median, min 5.8 5.4 5.7 5.7

Range, min 3.1-32.0 3.1-33.1 3.4-31.8 3.4-31.0

Duration of 12% response

No. patients* 63 77 52 57

Mean ± SD, hr 2.8 ± 2.3 3.6 ± 2.4 2.8 ± 2.2 2.6 ± 2.4

Median, hr 2.0 4.0 2.1 1.0

Range, hr 0.2-6.0 0.2-6.1 0.2-6.1 0.2-6.0

Time to 15% response onset

No. patients* 48 63 42 50

Mean ± SD, min 12.3 ± 9.9 9.5 ± 7.9 13.2 ± 9.7 13.6 ± 9.8

Median, min 5.9 5.4 8.9 10.6

Range, min 3.1-31.7 3.1-30.3 3.4-31.8 3.4-31.2

Duration of 15% response

No. patients* 48 63 42 50

Mean ± SD, hr 2.4 ± 2.3 3.6 ± 2.4 2.8 ± 2.2 2.8 ± 2.3

Median, hr 0.9 4.0 2.0 2.0

Range, hr 0.2-6.0 0.2-6.0 0.2-6.1 0.2-6.0

MDPI = Multidose dry powder inhaler; FEV7 = forced expiratory volume in 1 s; PEP = peak expiratory flow (rate); SD =

standard deviation.

*The number of patients with data at each visit.

Table 5 Results for daily diary variables, full analysis set

Variable Placebo MDPI Albuterol MDPI p Value

Group ( n = 92) Group (n = 92)

Change from baseline to TD 21 in percentage of the

following:

Symptom-free days -1.38 3.85 0.07

Rescue medication-free 24-hr periods -2.44 1.69 0.14

Nights without asthma-related awakenings 2.77 0.41 0.22

LS mean change from baseline to TD 21 in the following:

Daily (daytime) asthma symptom score 0.00 -0.09 0.25

Asthma-related nocturnal aw akenings/w k -0.31 0.05 0.22

Daily A.M. predose PEF, L /m in 4.84 9.55 0.17

Puffs of rescue medication per 24-hr periods -0.05 -0.06 0.93

Puffs of rescue medication per evening -0.02 -0.03 0.91

MDPI = Multidose dry powder inhaler; TD = treatment day; LS = least squares; PEF = peak expiratory flow (rate).

tients were discontinued because they received a pro treatment with two inhalations of albuterol MDPI 90

hibited medication (i.e., systemic corticosteroids). pg four times daily (a total daily dose of 720 pg) was

effective for improving pulm onary function and was

DISCUSSION generally well tolerated. After 3 weeks of treatment,

This randomized trial conducted in children with the patients who received albuterol MDPI had signifi

asthma, ages 4-11 years, demonstrated that 3 weeks of cantly greater baseline-adjusted PPPEV, AUC0_6 (pri-

Aliergy and Asthma Proceedings 35

Table 6 Summary of treatment-emergent adverse previous results indicate that chronic use of (3 agonists

events occurring in at least 2% of patients in any in asthma may result in more exacerbations, the pres

treatment group, safety population ent study did not observe an increase as a result of

albuterol MDPI treatment in comparison with pla

Adverse Event* Placebo MDPI Albuterol MDPI cebo.17 In the present study, nearly 100% of patients

Group (n = 92) Group (n = 93) were previously taking medication for obstructive air

Headache 4 (4.3) 3 (3.2) way disease. It may be a possibility that these concom

Cough 3 (3.3) 3 (3.2) itant medications provided some level of protection

Pyrexia 3 (3.3) 2 (2.2) from tachyphylaxis.

Abdominal pain, 3 (3.3) 0 (0.0) The four times daily administration of albuterol

upper MDPI and placebo MDPI over a 3-week treatment

URTI 3 (3.3) 0 (0.0) period was well tolerated among pediatric patients,

Ligament sprain 3 (3.3) 0 (0.0) with comparable tolerability profiles between the treat

Seasonal allergy 2 (2.2) 0 (0.0) ment groups. Notably, four times daily dosing is not

Vomiting 1 (1.1) 3 (3.2) the recommended dosing schedule; more typically, as-

Nasopharyngitis 1 (1.1) 2 (2.2) needed dosing is used in clinical practice. Therefore,

Oropharyngeal 1(1.1) 2 (2.2) any AEs or attenuation of effect would likely be much

pain less with the less frequent dosing used in the real-

world setting. The overall incidence of treatment-emer

MDPI = Multidose dry powder inhaler; URTI = upper gent AEs was ^4%. There were no serious AEs, and

respiratory tract infection.

none of the events was considered to be treatment

*Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities preferred related. Nine patients experienced asthma exacerba

terms.

tions; eight of the nine cases recovered or were recov

ering. These findings were generally consistent with

the known tolerability profile of albuterol and other

mary end point) and PEF AUC0_6 (secondary end short-acting /32-adrenergic agonists and consistent with

point) compared with those who received placebo. In two previously conducted studies in adults on the

addition, albuterol MDPI was numerically superior to tolerability of albuterol MDPI administered four times

placebo MDPI for most of the other efficacy end points, daily for a total daily dose of 720 pg over a 12-week

including baseline-adjusted PPFEVj AUC0_6 and PEF period.10

AUC0_6 on TDs 1 and 22, and maximum percentage

change from baseline in FEV], and PEF. However, the p

values for these variables were not adjusted for multi CONCLUSION

plicity. In a recent study conducted in children 4-11 Albuterol MDPI, administered four times daily for 3

years of age, albuterol MDPI and albuterol HFA pro weeks, improved pulmonary function in pediatric pa

vided similar improvements in pulmonary function tients significantly better than placebo. Clinical effects

compared with placebo when administered as a single were evident within 5 minutes after dosing and were

90- or 180-/rg dose.16 maintained for >2 hours, with no evidence for dimi

More patients treated with albuterol MDPI (52.2%) nution of the effect with chronic use. The four times

than patients who received placebo MDPI (17.4%) re daily administration was generally well tolerated in

sponded to therapy, as assessed by the percentage of pediatric patients. The U.S. Food and Drug Adminis

patients who achieved a 15% increase in FEVj from tration reviewed the data from this clinical trial in its

baseline within 30 minutes after dosing. The median evaluation, and the April 2016 approval of the albu

time to achieve this response was rapid, with a median terol MDPI expanded the indication for treatment of

time to onset of ~6 to 9 minutes for an increase of 15% patients >4 years of age.

in FEVj from baseline within 30 minutes of dosing.

The improvements from baseline in FEVj noted in

REFERENCES

the patients treated with albuterol MDPI were similar

1. Expert Panel Report 3 (EPR3): Guidelines for the Diagnosis and

on day 1 and on day 22, which indicated that there was

Management of Asthma. Bethesda, MD: National Heart, Lung,

no tachyphylaxis as a result of chronic albuterol use and Blood Institute, US Department of Health and Human

over the 3-week study period. The improvements Services, 2007.

noted on day 1 indicated the effectiveness of albuterol 2. Ramsdell JW, Klinger NM, Ekholm BP, and Colice GL. Safety of

MDPI as a rescue inhaler on an as-needed basis for long-term treatment with HFA albuterol. Chest 115:945-951,

1999.

quick relief, whereas the continued effectiveness noted

3. Tinkelman DG, Bleecker ER, Ramsdell J, et al. Proventil HFA

on day 22 indicated that patients would continue to and ventolin have similar safety profiles during regular use.

experience benefit even after repeated use. Although Chest 113:290-296, 1998.

36 January-February 2017, Vol. 38, No. 1

4. Harvey JE, and Tattersfield AE. Airway response to salbutamol: roalkane for the treatment of persistent asthma: Results of two

Effect of regular salbutamol inhalations in normal, atopic, and randomized double-blind studies. Clin Drug Investig 36:55-65,

asthmatic subjects. Thorax 37:280-287, 1982. 2016.

5. Taylor DR, Drazen JM, Herbison GP, et al. Asthma exacerba 12. Ratnayake A, Taveras H, Iverson H, and Shore P. Pharmacoki

tions during long term beta agonist use: Influence of beta(2) netics and pharmacodynamics of albuterol multidose dry pow

adrenoceptor polymorphism. Thorax 55:762-767, 2000. der inhaler and albuterol hydrofluoroalkane in children with

6. Burkhart PV, Rayens MK, and Bowman RK. An evaluation of asthma. Allergy Asthma Proc 37:370-375, 2016.

children's metered-dose inhaler technique for asthma medica 13. Eigen H, Bieler H, Grant D, et al. Spirometric pulmonary func

tions. Nurs Clin North Am 40:167-182, 2005. tion in healthy preschool children. Am J Respir Crit Care Med

7. Price DB, Pearce L, Powell SR, et al. Handling and acceptability

163:619-623, 2001.

of the Easi-Breathe device compared with a conventional me

14. Quanjer PH, Borsboom GJ, Brunekreef B, et al. Spirometric

tered dose inhaler by patients and practice nurses. Int J Clin

reference values for white European children and adolescents:

Pract 53:31-36, 1999.

8. Given J, Taveras H, and Iverson H. Prospective, open-label Polgar revisited. Pediatr Pulmonol 19:135-142, 1995.

evaluation of a new albuterol multidose dry powder inhaler 15. Beydon N, Davis SD, Lombardi E, et al. An official American

with integrated dose counter. Allergy Asthma Proc 37:199-206, Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement: Pul

2016. monary function testing in preschool children. Am ] Respir Crit

9. ProAir RespiClick [package insert], Horsham, PA: Teva Respi Care Med 175:1304-1345, 2007.

ratory; 2016. 16. Qaqundah PY, Taveras H, Iverson H, and Shore P. Albuterol

10. Raphael G, Taveras H, Iverson H, et al. Twelve- and 52-week multidose dry powder inhaler and albuterol hydrofluoroalkane

safety of albuterol multidose dry powder inhaler in patients versus placebo in children with persistent asthma. Allergy

with persistent asthma. J Asthma 53:187-193, 2016. Asthma Proc 37:350-358, 2016.

11. Kerwin EM, Taveras H, Iverson H, et al. Pharmacokinetics, 17. Taylor DR, Sears MR, Herbison GP, et al. Regular inhaled beta

pharmacodynamics, efficacy, and safety of albuterol (salbu- agonist in asthma: Effects on exacerbations and lung function.

terol) multi-dose dry-powder inhaler and ProAir® hydrofluo- Thorax 48:134-138, 1993. □

Allergy and Asthma Proceedings 37

Copyright of Allergy & Asthma Proceedings is the property of OceanSide Publications Inc.

and its content may not be copied or emailed to multiple sites or posted to a listserv without

the copyright holder's express written permission. However, users may print, download, or

email articles for individual use.

You might also like

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- Yardi Commercial SuiteDocument52 pagesYardi Commercial SuiteSpicyNo ratings yet

- Gamma World Character SheetDocument1 pageGamma World Character SheetDr8chNo ratings yet

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Windows Keyboard Shortcuts OverviewDocument3 pagesWindows Keyboard Shortcuts OverviewShaik Arif100% (1)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Skype Sex - Date of Birth - Nationality: Curriculum VitaeDocument4 pagesSkype Sex - Date of Birth - Nationality: Curriculum VitaeSasa DjurasNo ratings yet

- PLJ-8LED Manual Translation enDocument13 pagesPLJ-8LED Manual Translation enandrey100% (2)

- Carbapenamses in Antibiotic ResistanceDocument53 pagesCarbapenamses in Antibiotic Resistancetummalapalli venkateswara raoNo ratings yet

- Amex Case StudyDocument12 pagesAmex Case StudyNitesh JainNo ratings yet

- DHF Menurut WHO 2011Document212 pagesDHF Menurut WHO 2011Jamal SutrisnaNo ratings yet

- 838 3348 1 PBDocument7 pages838 3348 1 PBararapiaNo ratings yet

- ContentServer - Asp 12Document8 pagesContentServer - Asp 12ararapiaNo ratings yet

- ContentServer - Asp 11Document12 pagesContentServer - Asp 11ararapiaNo ratings yet

- Jurnal 1Document9 pagesJurnal 1ararapiaNo ratings yet

- Dbfnbefgejgfd Hbcvnbcxnvjhs DJVBNBNDVBNB Efewjhbjgbrejn Jfgvbjbwihwjhq RLNF, Sncnesrkfg NekrnfmttttttttDocument3 pagesDbfnbefgejgfd Hbcvnbcxnvjhs DJVBNBNDVBNB Efewjhbjgbrejn Jfgvbjbwihwjhq RLNF, Sncnesrkfg NekrnfmttttttttararapiaNo ratings yet

- Jurnal 2Document11 pagesJurnal 2ararapiaNo ratings yet

- ContentServer - Asp 13Document14 pagesContentServer - Asp 13ararapiaNo ratings yet

- PP Vascularisasi ExtremitasDocument49 pagesPP Vascularisasi ExtremitasararapiaNo ratings yet

- Jurnal FatonDocument8 pagesJurnal FatonararapiaNo ratings yet

- ReferenceDocument6 pagesReferencededyjossNo ratings yet

- 1-Surat Al-FatihahDocument3 pages1-Surat Al-Fatihahvaschuk_8No ratings yet

- Biosynthesis of HemoglobinDocument48 pagesBiosynthesis of HemoglobinTania AzhariNo ratings yet

- Medical Garage FairDocument13 pagesMedical Garage FairararapiaNo ratings yet

- Dogma Sentral Dalam Biologi Kuliah23 OktoberDocument25 pagesDogma Sentral Dalam Biologi Kuliah23 OktoberararapiaNo ratings yet

- FK YarsiDocument1 pageFK YarsiararapiaNo ratings yet

- Bahan Kuliah 2011 EBM - PendahuluanDocument34 pagesBahan Kuliah 2011 EBM - PendahuluanararapiaNo ratings yet

- Medical Garage FairDocument13 pagesMedical Garage FairararapiaNo ratings yet

- Bahan Kuliah 2011 EBM - PendahuluanDocument34 pagesBahan Kuliah 2011 EBM - PendahuluanararapiaNo ratings yet

- Effective Note Taking MS 02.09.2013Document21 pagesEffective Note Taking MS 02.09.2013ararapiaNo ratings yet

- Bahan Kuliah 2011 EBM - PendahuluanDocument34 pagesBahan Kuliah 2011 EBM - PendahuluanararapiaNo ratings yet

- Course Handbook MSC Marketing Sept2022Document58 pagesCourse Handbook MSC Marketing Sept2022Tauseef JamalNo ratings yet

- Technical CommunicationDocument35 pagesTechnical CommunicationPrecious Tinashe NyakabauNo ratings yet

- Self-Learning Module in General Chemistry 1 LessonDocument9 pagesSelf-Learning Module in General Chemistry 1 LessonGhaniella B. JulianNo ratings yet

- Trabajo de Investigación FormativaDocument75 pagesTrabajo de Investigación Formativalucio RNo ratings yet

- Module 2 What It Means To Be AI FirstDocument85 pagesModule 2 What It Means To Be AI FirstSantiago Ariel Bustos YagueNo ratings yet

- Funny Physics QuestionsDocument3 pagesFunny Physics Questionsnek tsilNo ratings yet

- Wei Et Al 2016Document7 pagesWei Et Al 2016Aline HunoNo ratings yet

- EE114-1 Homework 2: Building Electrical SystemsDocument2 pagesEE114-1 Homework 2: Building Electrical SystemsGuiaSanchezNo ratings yet

- Operating Instructions: Blu-Ray Disc™ / DVD Player BDP-S470Document39 pagesOperating Instructions: Blu-Ray Disc™ / DVD Player BDP-S470JhamNo ratings yet

- TSGE - TLGE - TTGE - Reduce Moment High Performance CouplingDocument6 pagesTSGE - TLGE - TTGE - Reduce Moment High Performance CouplingazayfathirNo ratings yet

- Past Paper Booklet - QPDocument506 pagesPast Paper Booklet - QPMukeshNo ratings yet

- Monitoring Tool in ScienceDocument10 pagesMonitoring Tool in ScienceCatherine RenanteNo ratings yet

- Classification of Methods of MeasurementsDocument60 pagesClassification of Methods of MeasurementsVenkat Krishna100% (2)

- Activity2 Mba 302Document2 pagesActivity2 Mba 302Juan PasyalanNo ratings yet

- What Is Chemical EngineeringDocument4 pagesWhat Is Chemical EngineeringgersonNo ratings yet

- Case Study On Vivekananda Flyover BridgeDocument8 pagesCase Study On Vivekananda Flyover BridgeHeta PanchalNo ratings yet

- Goes 300 S Service ManualDocument188 pagesGoes 300 S Service ManualШурик КамушкинNo ratings yet

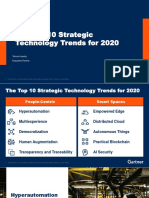

- The Top 10 Strategic Technology Trends For 2020: Tomas Huseby Executive PartnerDocument31 pagesThe Top 10 Strategic Technology Trends For 2020: Tomas Huseby Executive PartnerCarlos Stuars Echeandia CastilloNo ratings yet

- IS 2848 - Specition For PRT SensorDocument25 pagesIS 2848 - Specition For PRT SensorDiptee PatingeNo ratings yet

- Cisco Lab 2.2.4.3Document5 pagesCisco Lab 2.2.4.3vcx100100% (6)

- Mono - Probiotics - English MONOGRAFIA HEALTH CANADA - 0Document25 pagesMono - Probiotics - English MONOGRAFIA HEALTH CANADA - 0Farhan aliNo ratings yet

- Homer Christensen ResumeDocument4 pagesHomer Christensen ResumeR. N. Homer Christensen - Inish Icaro KiNo ratings yet

- Insert BondingDocument14 pagesInsert BondingHelpful HandNo ratings yet