Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Art Materiality and The Meaning of Bein PDF

Uploaded by

HansOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Art Materiality and The Meaning of Bein PDF

Uploaded by

HansCopyright:

Available Formats

5

Art, Materiality, and the Meaning of Being: Heidegger on

the Work of Art and the Significance of Things

Philip Tonner1

y

Introduction: Ereignis

op

In the ‘Addendum’ to ‘The Origin of the Work of Art’, Heidegger tells us that

C

art belongs to ‘appropriation’.2 It is apt that in the years leading up to the

publication of this revised version of his essay in 1960, he should note this

deep connection. It is this term – Ereignis – that Heidegger began to use for

his central concern, the finite disclosure of Being qua meaningful presence

f

in conjunction with the opening up of Dasein qua finitude, in just the period

when he composed ‘The Origin of the Work of Art’.3 Ereignis is Heidegger’s

oo

term for ‘disclosure as such’ and this term names the occurrence of Being ‘in

its truth’; Ereignis signals our being appropriated into our openness, it is that

movement of our being opened up by virtue of our essential finitude in such

a way as to creatively receive and conserve a meaningful world of things.

Ereignis, and so art, is indelibly historical: the event of appropriation is the

Pr

event of the coming to be of historical worlds.4

It is because of this essential connection to Ereignis that the question of art

is a question of ‘origins’. Great art for Heidegger is a world-opening event and

true art history is world history: a great art work, on Heidegger’s account, is

an event that enshrines the meaning of Being (the way that things can become

meaningfully present) that constitutes a historical community. The question

of art for Heidegger is essentially related to the question of truth. Specifically,

art is a paradigmatic case of the kind of historically emerging truth that

Heidegger is concerned with in texts of the 1930s, such as Contributions to

Philosophy (GA 65)5 and Introduction to Metaphysics.6 In fact, Heidegger’s

account of art is bound up with his idea of the ‘history of Being’, which is also

a history of truth.7

Heidegger book.indb 121 12/11/2013 2:43:13 PM

122 Heidegger and the Work of Art History

That is why he chose to investigate the question of art in terms of its origin.

However, what kind ‘of ‘origin’ is in question here, conceptual or actual?

Heidegger returns to Greece when considering the origin of the work of art and

the origin of the history of Being. In his later writings Heidegger suggests that

there have been successive worlds that have unfolded over the epochs of what

he calls the ‘history of Being’. Each epoch is constituted by a different world in

Heidegger’s sense and the succession of different worlds is accounted for by

the fact that the earth continues to resist our collective attempts to subdue it

and to incorporate it wholesale into a particular historical world.8

Yet there was art thousands of years before Greece. We may wonder if

pausing to consider such art might cast a different shadow over the question

of the origin of the work of art, if not of the exact nature of the ‘origin’ in

y

question for Heidegger, especially when we consider that Heidegger denied

that there was a ‘prehistory’ of art in the first version of his ‘Origin’ essay.9

op

What I would like to do in this chapter is to first enact such a pause by asking

what Heidegger might have had to say about Franco-Cantabrian cave art?10

Interestingly, that other thinker of art’s ‘origin’ in the twentieth century, George

Bataille, considered such prehistoric painting to be art’s actual origin.11 By

contrasting his view to that of Heidegger, we will be able to see that Heidegger

C

offers a quite different account of the origin of the ‘work of art’ than Bataille.

Yet both accounts border on one another and my discussion here will bring

out aspects of Heidegger’s account that might otherwise remain concealed.

From here I will return to Heidegger’s account of art on its own terms

f

and I will discuss the question of the work of art in terms of his ontology

of the ready-to-hand and present-at-hand. Here I will raise the question of

oo

materiality and so relate Heidegger’s account of art to his later discussion of

‘things’. There is, says Heidegger, ‘something stony in a work of architecture

… coloured in a painting … [and] spoken in a linguistic work’. This is the

work’s ‘thingly’ element and, so holds Heidegger, it compels us to say that ‘the

architectural work is in stone … the painting in colour … [and] the linguistic

Pr

work in speech’. Yet, Heidegger asks, ‘what is this self-evident thingly element

in the work of art?’12

I will suggest that in his writings and lectures from the late 1940s until

his death, Heidegger takes advantage of the space opened up by his

discussion of art to explore the notion of the ‘thing’ in terms that go beyond

his early categories of readiness-to-hand and presence-at-hand. Heidegger’s

philosophy of art can make a contribution to our understanding of the

materiality of things, including paintings, sculpture, and architectural objects,

all of which can sit side by side in the modern museum. From here I will

return to the question of the relationship of art history to world history. I will

intimate how art works and things materially enshrine the ‘meaning of Being’

constitutive of a particular culture and I will suggest why this is important

from an art-historical perspective.

Heidegger book.indb 122 12/11/2013 2:43:14 PM

Art, Materiality, and the Meaning of Being 123

Prelude: The History of Being

On Heidegger’s account, the history of Being is not to be thought of just as

the history of human conceptions of ‘Being’, or as the history of philosophy

qua metaphysics, or as a sequence of past events, or as the history of the West;

although, in one way or another, all of these notions are related to, and made

possible by, this idea. The limit of thinking of the history of Being only in

terms of one or more of these ideas is that it might lead one to think of history

(Historie) as a collection of more or less related past events, where the notion

of the ‘past’ is paramount, that are subsequently available to historiographical

study in the present. In contradistinction to this and in terms of the notion

of ‘historical reflection’ (introduced by Heidegger in Basic Questions of

y

Philosophy)13 we should think of the history (Geschichte) of Being as an event

(Geschehen) that constitutes a destiny (Geschick).14

op

Historical reflection on meaning or sense (Be-sinnung) is tasked with

understanding a historical ‘happening’ (Geschehen) that still involves human

agents because it has taken them over or taken them up in it and which only

gets an overall ‘point’ from the direction of its historical unfolding.15 As

such, history is not primarily concerned with what is ‘past’: rather, history

fC

is concerned with the future as a ‘coming towards’ where the meaning

of any historical event – and of history itself – is created by what comes to

pass through it. It is on the basis of this account that Heidegger will say that

genuine history is composed by ‘the goals of creative activity, their rank

and their extent’.16 This is the subject matter of historical reflection and such

oo

reflection attempts to get at the meaning of the events of history. Art works,

on this account, gain their significance – or their ‘Being’ – in terms of their

function of casting or throwing (forward) towards the ‘preservers’ of the work

the very way in which things can become meaningful and understood for

that group or civilization. That is, works of art are ‘projections’ where ‘the

Pr

concepts of an historical people’s nature, i.e., of its belonging to world history,

are formed for that folk, before it’.17

In ‘The Origin of the Work of Art’, Heidegger notes only three historical

(Western) worlds, the Greek, the medieval, and the modern. Elsewhere, he

recognizes a Roman world and an ‘early’ form of the modern world that

has not quite reached modernity’s consumerist maximum.18 Art’s historico-

political role is that particular works (especially non-representational works

such as the Greek temple and Gothic cathedral) gather together the different

inchoate narrative possibilities that are possible for a particular historical

people that remain embedded in their background practices. The work of

art will appropriate by composing these inchoate narrative possibilities into

world-opening works.19 Thus, works of art illuminate the style of a particular

cultural-historical world.20

Heidegger book.indb 123 12/11/2013 2:43:14 PM

124 Heidegger and the Work of Art History

Works of art focus and direct the lives of individuals while putting up for

decision the highest values of a group, what is to count as holy and what unholy.

That is, for Heidegger, a great work of art is a ‘cultural paradigm’ and the

function of such paradigms is to inaugurate the history of a community. Great

works do this by defining and determining how the beings that agents can

meet in their experience can show up as meaningful: the world opened by the

work is the horizon of beings. Great art, for Heidegger, includes all manner of

world-defining events, such as the building of a temple or cathedral and, as I

will suggest below, the painting of a cave. It is in this sense that on Heidegger’s

account art is essentially an origin and works of art reveal and open what

ordinarily remains out of site; and that is the world.21

y

Prehistoric Art: Heidegger and Bataille

op

For both Bataille and Heidegger, the question of art is directly related to the

question of origins: for Heidegger, art is the essence and origin of all particular

works of art while for Bataille, the question of art’s origin is essentially related

to the question of the origin of our species. Both Bataille and Heidegger were

C

pursuing their writings on art at the same time: Bataille had been writing

on prehistory and prehistoric art since the early 1930s and Heidegger had

been working on the text of his ‘Origin’ essay since 1935.22 To be sure, art

for Heidegger does not produce our species in a biological sense but it does

f

account for the origin of artists, audiences, and entire historical worlds. On

Heidegger’s account, the creation of a work of art is an event that opens up a

oo

historical world for a historical people.

For Heidegger, artists are not motivated by ‘fame’ and they are not affected

by ‘disregard’. Their works remain withdrawn from both ‘public’ and ‘private’

consumption: that is, their works are not objects that can be held up for

subjects (in a distinctly modern sense) as an object of aesthetic appreciation.

Pr

Works of art do not ‘belong to man’.23 Rather, works form the ‘site of decision

of the rare ones’, poets who articulate the truth of the Dasein (Being-t/here-

now) of the people and thinkers who elucidate the way in which things can

become meaningful for a people, as this was opened up by the poet.24 The

work of art belongs to what Heidegger designated a ‘going under’ that alone

can become ‘foundational history’, the kind of history that leaves in its wake

a clearing of Being: this is the moment of the opening up of a historical world

and this description of it is tremendously suggestive in terms of an account of

cave art where artists would actually go under the ground or into a mountain

to bring forth their works. These works were probably visited again, possibly

by a select few, only on rare and exceptional occasions.25

Artworks, for Heidegger, are self-subsistent. They lack a relation to beings

in their familiar organization. Yet the self-subsistence of the work marks it

Heidegger book.indb 124 12/11/2013 2:43:14 PM

Art, Materiality, and the Meaning of Being 125

out as something created; self-subsistence relates the work to its creator but

at the same time marks that creator’s Dasein as ‘sacrifice’. Here, of course, we

encounter a theme central to Bataille’s account of art – namely, sacrifice. But

sacrifice, on Heidegger’s account, is not a literal sacrifice, nor is it an event of

cultural mourning or revering. But, for Bataille, who was also interested in

the question of the holy and the unholy, the sacred and the profane, and with

the way in which the world is meaningfully there for human beings, unlike

Heidegger, the origin of art is bound up with transgression, with horror,

with the erotic and, ultimately, with actual death. For Heidegger, by contrast,

the sacrifice central to the creation of art is thought of as an agent’s reticent

dwelling in awaiting that which is given over to a group as the meaning of

Being constitutive of their ‘age’.26

y

The kind of sacrifice that interests Heidegger is sacrifice unto the abyss of

Being: in other words, sacrifice unto das Ereignis; sacrifice unto the epochal

op

play of disclosure and concealment. In such sacrifice the artist a historical

agent (amongst and amidst other agents) awaits what is given over to them

in their historical dwelling as the truth of Being.27 Great art is world-historic.28

Heidegger says, ‘it is only work that within the mutual calling forth of the

sway of the earth and the sway of the world puts to decision the sway of gods

fC

and the ownmost of man’ (italics in the original).29

Insofar as a work of art ‘works’ in Heidegger’s sense of the term it ‘holds

open the open region of the world’.30 Just because of this, the work of art can

preserve the space of questioning wherein that which was once inchoate

in the background practices of the people is now seen to be intrinsically

mysterious and worthy of question and is so put up for decision in terms of

oo

how things are going to matter for those who dwell in the world opened up

by the work. Artworks put up for decision the highest values (the gods) of a

group while asking after what will prove essential for human dwelling in that

world. Because of this a true art history for Heidegger is also world history

since a reading of such works ought to reveal dimensions of historical worlds

Pr

that have been opened up and appropriated by agents. The promise of such

a world-historic reading of a work of art is that it might reveal the way in

which things are and/or were meaningful for a historical people insofar as

that meaningfulness was composed or materialized in the work: a historically

reflective reading of the work will elicit its meaning as world opening event.

When the work of art is taken as a cultural paradigm (in the sense of opening

a cultural world) it allows just about anything whatsoever to count as art just so

long as the work in question qua paradigm ‘holds open the open region of

the world’.

By contrast, for Bataille, art’s origin is essentially related to the question of

the actual origin of our species. His view is that the birth of art in the Upper

Palaeolithic caves of Europe ‘followed upon the physical completion of the

human being’.31 Guerlac suggests a reading of Bataille’s 1955 work on Lascaux

Heidegger book.indb 125 12/11/2013 2:43:14 PM

126 Heidegger and the Work of Art History

as a ‘parodic myth of origins’ where the ‘miracle of Greece’ is substituted for

‘the miracle of Lascaux’; the classical world is substituted by the primitive

world and the world of reason is replaced by the world of the sacred; and if

it was the case that the miracle of Greece heralded man the rational animal,

then the miracle of Lascaux, on Bataille’s account, heralds man the ‘religious

animal’.32

For Bataille, the distinction between the sacred and the profane is

absolute: it admits of no degrees, and passage from one to the other requires

a transformation. One way that this can occur is in art: art expresses religious

transgression and Bataille’s study of Lascaux presents transgression in

relation to a ‘sacred moment of figuration’.33 Now, transgression, as Foucault

suggested, is a ‘gesture concerning the limit’.34 It is a ‘flash of lightening’

y

where both limit and transgression depend upon and belong to one another.

It is transgression that is the focal point of Bataille’s reading of Lascaux

op

precisely because it is his view that human societies are founded upon

prohibition.35

The act of painting transgresses the ordinary round of profane life and

gestures towards the sacred realm. Bataille says, ‘A work of art, a sacrifice

contain something of an irrepressible festive exuberance that overflows the

C

world of work, and clash with, if not the letter, the spirit of the prohibitions

indispensable to safeguarding this world’.36 For Bataille great art is excessive

and essentially transgressive of an existing world, whereas for Heidegger it is

not the transgressing of a world that is at stake, but its originary opening. Art,

f

like sacrifice, on Bataille’s account, transgresses the world of work in festivity

and play and the moment of sacrifice ‘restores to the sacred world that which

oo

servile use has degraded [and] rendered profane’.37

While the art of Greece does represent a miracle for Bataille, the light

emanating from it is that of ‘broad day’. In other words, this is the light of the

creative powers of fully modern humans. The light of dawn, by contrast, that

emanates from Lascaux is, while tentative, nevertheless ‘the most dazzling

Pr

of all’.38 At Lascaux, newly born ‘mankind’ attempted to measure ‘the extent

of its inner, its secret wealth: its power to strive after the impossible’.39 In fact,

the miracle of Lascaux inaugurates a fourfold logic of transfiguration: la bête

humaine is transfigured from animal to man and then into its proper being as

religious animal; while the paintings in the cave transfigure the animal into

a beautiful representation, they also bestow the animal so represented with

a force of prestige; the final transfiguration is that of the artists themselves

who are transformed from ‘cavemen’ animals into a being that ‘resembles

us’, and that is, into Homo ludens ‘man the player’ as opposed to Homo faber

‘working man’.40

Art constitutes nothing less than the chronological origin of Homo sapiens.

He says,

Heidegger book.indb 126 12/11/2013 2:43:14 PM

Art, Materiality, and the Meaning of Being 127

my subject is the most ancient art, that is to say, art’s birth, not some one of its

later aspects or refinements. [At Lascaux] Resolutely, decisively, man wrenched

himself out of the animal’s condition and into ‘manhood’: [and] that abrupt,

most important of transitions left an image of itself blazed upon the rock in

this cave.41

Chronologically, the most ancient art is art’s birth or origin. But this birth is

also the ‘moment’ of the origination of the species Homo sapiens sapiens. It is this

‘moment’ that has come down to us on the wall of Lascaux. Like Heidegger,

Bataille privileges the origin for it is there that what emerges does so in its

most vibrant form. Unlike Bataille, for Heidegger, the ‘origin’ (Ursprung) of the

artwork is, paradoxically, ‘art’. This is because, unlike Bataille, Heidegger is

not after an actual historical origin (or a causal one, where the artist would be

y

the causal origin of their works) of art. While the ‘greatest’ art by Heidegger’s

estimation occurred in eighth- to fourth-century Greece, this is nevertheless

op

not the historical origin of art.42 Ultimately, Heidegger’s question is about the

logical/conceptual origin of art where the origin in question will account for

the nature of what issues from its source.43

For Bataille, the very birth of art, and the afterlife of that birth, remains

‘blazed’ upon the cave walls at Lascaux. Humanity, as something we recognize

fC

because it resembles us, originates with the birth of art: Homo sapiens is Homo

ludens; ‘we’ are differentiated from the animal and from the no-longer-animal-

but-not-yet-man Homo faber or Neanderthal man by our ability, not to make

(more complex) tools, but by our ability to play and to create ‘useless’ things

like works of art that transfigure the world by virtue of their beauty.44 This

uselessness of art will be put in question for Heidegger since works of art do

oo

have a job to do on his account. Yet, as we will see, they are neither ready-

to-hand nor present-at-hand. The uselessness of art in fact will be thought

of in terms of the works’ materiality and resistance to total control and

consumption by human beings. Just as for Heidegger, a great work of art, like

the Temple of Poseidon at Paestum,45 is the materialization of the meaning of

Pr

being of an age, so too for Bataille, Lascaux is the materialization of the epoch

that produced it.46

Heidegger does not devote attention to such art in the way that Bataille

does (for him, art can ‘only be or not be as historical’ precisely because when

a ‘peoples’ art begins so too does their history). As such, the very notion of

‘prehistoric art’ is a non-starter for him, but what can we say about it from

his broad perspective?47 On Heidegger’s terms we should say that the image

on the cave wall represents the originary opening up of a historical world

for the creators and preservers of these works. In its original sitting in the

cave, the ‘work’ of the work of art is occurring: it is opening up the world of

the prehistoric peoples that created it. Art works in their original sitting first

give ‘to things their look and to men their outlook on themselves’.48 This is a

phenomenological claim, not a historical one, and the ‘prehistoric’ peoples

Heidegger book.indb 127 12/11/2013 2:43:14 PM

128 Heidegger and the Work of Art History

that created these works of art were just as ‘historical’ in Heidegger’s sense as

the artists of later times. Insofar as a work ‘holds open the open region of the

world’, it counts as a work of art qua cultural paradigm and on this account

pre-Greek Upper Palaeolithic artworks count as cultural paradigms whether

they fit into Heidegger’s preferred Greek paradigm or not. Specific artworks

can open up a ‘Greek world’ or a ‘medieval world’, and so on a Heideggerian

account, cave art such as that represented at Lascaux or Nieux opened up a

‘hunter-gatherer world’. While we can no doubt mount an argument to the

effect that cave art opened up a world of shamans who would send their souls

to a world of spirits or a world of sorcerers who would attempt to affect a

successful hunt nevertheless, on Heidegger’s terms, the ‘work’ of the work of

art qua opening up a world is occurring.49

y

For Bataille, transgression is the organizing power in human life and it is

by virtue of its dynamism that the dual birth of art and humanity occurs. For

op

Heidegger, the organizing or ‘enabling power’ that issues Dasein is the event

of appropriation to which art and human agents belong. For Bataille, it is

prohibition that opens up a historical world; for Heidegger it is the work of

art itself that does this. For Bataille and Heidegger great art is an origin that

involves sacrifice but for Bataille this sacrifice is conceived of as a making

C

amends.50 For Heidegger, it is sacrifice unto the abyss of Ereignis opened in

us by our finitude. The abyss that Bataille recognizes is ‘opened in us by

eroticism and death’.51

f

Heidegger and Works of Art

oo

Art is fundamentally historical and Heidegger’s account of it is holistic, all the

aspects identified by him are equally basic. For Heidegger, the broad general

social practice of ‘art’ is the origin of individual works of art, of the artists who

create them and of the audiences who preserve the works so created. We can

Pr

hope to understand art, on his terms, only if we understand this broad social

practice. What art does that distinguishes it from other social practices – its

central ‘work’ – is that art ‘is truth setting itself to work’.52

Art is a particular form of disclosure (aletheia), and by way of the disclosure

characteristic of art what Heidegger called the ‘meaning of Being’ in Being and

Time can be determined.53 Yet the category of art is an uncomfortable fit for the

categories that relate to objects as these are elaborated in Being and Time. A work

of art is neither ready-to-hand nor present-at-hand but it shares features that

are common to both of these categories.54 Ready-to-hand objects (or beings)

are items that are available to an agent in terms of that agent’s understanding

and interest. Such items can be put to work by an agent in terms of their

projects and tasks. Ready-to-hand items are useful tools and such items are

structurally intelligible to agents because of their intrinsic reference to their

Heidegger book.indb 128 12/11/2013 2:43:14 PM

Art, Materiality, and the Meaning of Being 129

use by such agents. In Being and Time, the category of equipment is a paradigm

case of the available.

Items that occur without such a ‘worldly’ relationship to pragmatic use

are not ready-to-hand: by contrast, they are present-at-hand.55 Such things

are objects that have not been appropriated into a worldly context in terms

of their relationship to an agent’s understanding, interest, and pragmatic

use. Such entities are beings taken as occurrent; they are discrete objects that

bear certain properties, such as colour, weight, height, and so on, and these

properties are those that objects possess independently of any reference to a

human being’s use for them.56

What kind of thing then is a work of art? Works of art, such as van Gogh’s

Pair of Shoes or Dali’s Christ of St John of the Cross, display a distinctive ‘thingly’

y

quality. There is ‘something stony in a work of architecture … coloured in a

painting [and] spoken in a linguistic work’.57 But a work of art has no specific

op

purpose, like a hammer or a steering wheel does. In such cases the specific

materiality of the useful object is intrinsic to, and is fully consumed by, its

use (the hardness of steel necessary for a good hammer; the tactile nature of

the steering wheel necessary for a good grip: such ‘properties’ of the tool are

subordinate to its use). Yet works of art are produced by human beings, just

fC

like tools are produced. And they are fashioned out of the material world

that we encounter all around us, whether that world is subordinated to a

particular task or not.

So, works of art contain, like a present-at-hand pebble on the road, and

a ready-to-hand piece of equipment, like the hammer, a distinctive ‘thingly’

material component. It is this ‘thingly’ element that compels us to say that

oo

‘the architectural work is in stone’ and so on.58 But the nature of this ‘thingly’

dimension of the work is by no means transparent. Perhaps, then, it is

unsurprising that Heidegger should begin his questioning of art in his ‘Origin’

essay by asking ‘what is this self-evident thingly element in the work of art?’59

Heidegger begins to explore this question in terms of the definitions of

Pr

objects that have come to light in the Western tradition of philosophy and he

finds that none of the three traditional definitions of ‘thingness’ (as a ‘bearer of

traits’, as the ‘unity of a manifold of sensations’, and as ‘formed matter’) will

do. This is because in each case the thing is defined in terms of its relationship

to lived experience or to its possible relationship with a subject.60 Insofar as art

is thought as aesthetics (aisthēsis, Ästhetik), as an essentially human-centred

leisure activity where consumable ‘lived-experience’ (Erlebnis) is what counts,

the work of art will be transformed into an object that exists solely for our

subjective apprehension and consumption.

In an important sense such works have ceased to ‘work’ in the sense

that Heidegger is interested in. Such works of art are ‘bygone’. Due to their

objectification by subjects they have passed into the realm of ‘tradition and

conservation’.61 They have entered the culture industry and are housed

Heidegger book.indb 129 12/11/2013 2:43:14 PM

130 Heidegger and the Work of Art History

in museums and galleries and private collections. A great work of art is a

bringing forth; it is an event that opens up a historical world for a historical

people. Historical worlds ebb and flow and when they end, like the Greek and

the medieval worlds, their great art works are no longer alive because they are

no longer ‘opening up’ their worlds in the originary way that they once did.

Whereas in their ‘original sitting’, they first gave ‘to things their look and to

men their outlook on themselves’, when they die they pass into tradition.62 That

is, they become museum pieces (although, see Heidegger’s Sojourns where he

hints that such ‘museal art’ might preserve an afterglow that gestures towards

the works’ original ‘shining of truth’). Further, on Heidegger’s account the

moment of objectification that turns a work of art into an object fit for our

‘appreciation and enjoyment’ is that ‘element in which art dies’.63 It is in this

y

context that the modern concept of the museum as mausoleum is plausible (as

Adorno suggested and as Heidegger would seem to agree).64 Museums and

op

galleries are the storehouse of works of art that exist solely for our subjective

apprehension and consumption. Rather than existing as an object of ‘aesthetic

connoisseurship’ in a museum or gallery, or as made available in a ‘science’ by

the art historian, on Heidegger’s account the work of art belongs in the agora

as a public truth event.65

C

In fact, ‘aesthetics’, like ‘metaphysics’, is something that Heidegger argues

must be overcome. The art that is capable of doing so is an art that thematizes

the ‘other’ of beings (Being/world) rather than attempting to represent it by,

for example, turning it into a metaphysical super entity or by transforming

f

it into something known.66 Such art allows the ‘enigma’ (that there is Being)

oo

to presence ‘as the enigma’.67 It does not attempt to grasp in representational

thinking that which cannot be grasped by it: such art will not attempt to

transfigure what is unknown and unknowable into something graspable by a

subject in representational or metaphysical thought.68

Pr

Things Again

Despite the failure of the traditional definitions of thinghood, the definition of

the thing as formed matter intrigues Heidegger. This is because it recalls the

‘thingly’ character of the ready-to-hand insofar as such items are produced

by human agents. He reminds us that the Greeks, who had no concept

corresponding to the modern notion of ‘fine art’, understood the different

ways in which truth disclosure occurs generally as ‘bringing forth’. In such

terms they included art and craft under the name technē.69 Heidegger is not

concerned with ‘fine art’: he is concerned with ‘great art’, the kind of art that

can open the ‘truth of beings as a whole’, and such art corresponds to a Greek

paradigm on his account. It is because great art opens for ‘man’ the ‘truth of

Heidegger book.indb 130 12/11/2013 2:43:14 PM

Art, Materiality, and the Meaning of Being 131

beings as a whole’ that it is an ‘absolute need’.70 Overcoming aesthetics will

enable a return to that more Greek sense of art as technē.71

Despite his interest in things as compounds of matter and form, an

understanding of the work of art in these terms does not do justice to what

Heidegger designates the ‘work-character’ of the work. Works of art belong,

as works, ‘uniquely within the realm that is opened up’ by them and it is

there that ‘the work-being of the work occurs essentially’.72 Just as Heidegger

discovered the equipmental character of equipment (the Being of the ready-

to-hand, its usefulness) by bringing the reader before van Gogh’s painting of

a pair of shoes, so the work character of the work of art reveals itself in the

‘speaking’ of the painting. Here, in our nearness to the work, we are transported

from our everyday engagement with the world into the happening of truth.

y

The thematization inherent in van Gogh’s Pair of Shoes, for example,

discloses the pair of shoes in their use for their owner, in their reliability

op

and sturdiness, in their worn-in durability and material resistance to bodily

movement. Heidegger will say of this work that ‘Van Gogh’s painting is the

disclosure of what the equipment, the pair of peasant shoes, is in truth’.73 By

displacing us into the place of the event of truth, the ‘work’ of the work of

art is happening: it is an event where truth itself discloses the being of the

fC

shoes and opens up or brings forth the world of their use by their owner, who

Heidegger takes to be a peasant woman.74 Heidegger says,

From the dark opening of the worn insides of the shoes the toil-some tread of

the worker stares forth … In the shoes vibrates the silent call of the earth, its

quiet gift of the ripening grain and its unexplained self-refusal in the fallow

oo

desolation of the wintry field … This equipment [the shoes] belongs to the earth,

and it is protected in the world of the peasant woman.75

The notion of world in play here invokes the sense of a context of

significance: it is that open space wherein the owner of these shoes goes about

their daily business. When we look at the shoes in this painting, we see them

Pr

as work shoes of some kind. They are hobnail boots and Heidegger’s view

is that they belong to a peasant woman presumably because they look like

ones he’s seen such women wearing. In their worn-in state, these shoes ‘refer

to’ or ‘point at’ other aspects of the woman’s embodied-embedded life as her

life unfolds in her environing world: how she goes about her daily business

of sowing plants, how she is aware of the subtle changes in the weather, and

how such changes will impact upon her life.76 In sum, the world of the peasant

woman is disclosed to us (we preservers of the work) as a hermeneutic totality

as we read the painting: such bringing forth reveals the basic character of the

beings that this peasant woman meets as she dwells in her world.

Works of art are self-subsistent and the process of their creation is destructive

of the artist. In great art, the artist is inconsequential when compared to their

work. The artwork is not a symbolic object nor is it an ‘installation’ that gives

Heidegger book.indb 131 12/11/2013 2:43:14 PM

132 Heidegger and the Work of Art History

order to beings. Rather, it is the ‘clearing of be-ing as such’. Works of art do

not ‘belong to man’ as objects of subjective appreciation. Instead, Heidegger

suggests, art itself takes on the character of Da-sein, of being ‘the there’, the

site for the revelation of meaningful presence.77 As such, the work of art is

the site of decision for the ‘rare ones’, thinkers and poets capable of a ‘poetic

thinking’ that does not represent but that lets beings be. The work of art is

‘the gathering of purest solitude unto the ab-ground of be-ing’.78 On such an

account, art is no longer concerned with any striving concerned with ‘culture’.

Ab-ground names das Ereignis; the groundless abyssal play of revealing

and concealing that opens up historical worlds, and a historical world is an

all-governing open and relational expanse.79

y

The Work, the World, and Its History

op

So, a great work of art is a ‘cultural paradigm’ and such paradigms inaugurate

the history of a community. Heidegger deliberately widens the concept of

great art to include all manner of world-defining events such as the building

of a temple, the convening of rally, or the holding of the Olympic Games.80 In

C

all of these cases, works of art reveal the world.

The world is the basis on which the beings/entities that we meet in our

experience can be involved with one another and with us and it is our

acquaintance with the world in this sense that makes it possible for us to be

f

engaged with (act on, think about, and even experience) the entities that we

encounter as the kind of entities that they are. The ‘work’ of the work of art is

oo

to open up or disclose a world in order to disclose things in their emergence

as what and how they are.

Being, the basic general structure of what there is in the world, is only

ever revealed to agents who are engaged within a particular socio-historical

context and the truth in art is evident when art displays what Heidegger

Pr

calls the strife (Riss) between world and earth. This strife is Heidegger’s way

of expressing the tension between disclosure and concealment as essential

aspects of the work of art. While van Gogh’s painting reveals the world of

the peasant woman, it also reveals that world in terms of its emergence from

earth. The earth is that out of which the peasant’s world is fashioned, but not

in terms that would relegate it to passive matter. Earth relates to concealment

in Heidegger’s terms and so, a little loosely, it refers to the pre-cultural ground

that resists our attempts to establish coherent worlds upon it. It is just this

resistance to total control by us that is set into the work. The work maintains

within it the historical contingency and precariousness of human worlds.

For this reason, there is strife between world and earth, unconcealment and

concealment and it is at this level that the earth qua materiality or thingly

character of the work is understood by Heidegger.

Heidegger book.indb 132 12/11/2013 2:43:14 PM

Art, Materiality, and the Meaning of Being 133

Insofar as an artwork continues to do its work, and so does not become

a museum piece, it ‘holds open the open region of the world’.81 As such, it

preserves the space of questioning that puts up for decision how things are

going to matter for those who dwell in the world so opened by the work.

This is the first essential dimension of the ‘work’ of the work of art. In its

second essential aspect we encounter the materiality of the work, and we do

so in terms that illuminate its thingly character. Discussion of this ‘thingly’

character of the work enables Heidegger to come to terms with the materials –

such as ‘stone, wood, metal, colour, language, tone’– that the work is brought

forth in terms of and it is here that, by contrast with the piece of equipment

where the material from which it is fashioned is entirely consumed in its

production (by being subordinated to usefulness) in an art work, materiality

y

is brought forth and made visible for the first time in excess of use, function,

and form.82 To this extent, the materiality of art – its thingly character – is in

op

excess of technological calculation and mastery that Heidegger takes to be

evident in modern technology (Gestell).83

As excess-of-use materiality cannot be explained and brought under our

control in principle and works of art, through the materials out of which

they are fashioned and through their arrangement, reveal materiality’s self-

fC

secluding nature. Materiality, so understood, is earth and all material things

possess an ‘unlimited plenitude of aspects’ that lie beyond what is intelligible

to us. Now, it is Heidegger’s view that pausing to meditate on the materiality

of even the most humble thing may prompt in us an experience of their

‘astonishing mystery’.84

Any unconcealment of a being essentially involves a rift (Riss) between the

oo

intelligibility of world and the concealment of materiality (earth). This rift or

strife is ‘the intimacy with which opponents belong to each other’ and it is just

this rift that must cast itself back into earth in the materiality of the work: ‘[t]he

rift must set itself back into the gravity of stone, the mute hardness of wood,

the dark glow of colors’.85 Withdrawal necessarily accompanies disclosure

Pr

and the open region so opened is a space of ‘self-secluding and sheltering’.86 In

fact, it is the resistance of the earth to full disclosure that enables the particular

arrangement of the materials in the work to be set into it as figure (Gestalt),

and in all of this the materiality of the work is not fully consumed by use.

Precisely here Heidegger moves beyond the categories of Being and Time

where ‘things’ appear in terms of their use (ready-to-hand) or in terms of

occurrentness (presence-to-hand) and he will prepare the way for his later

conception of the thing as gathering the fourfold.87 As earth, materiality is

set free to be what it is and the human ‘createdness’ of the work is the aspect

where truth is set ‘in place’ as figure. Here the strife between concealment and

unconcealment composes itself and so composed, this strife/rift is the ‘fugue

of truth’s shining’.88 Truth needs materiality in order to happen at all and in its

composure truth sets materiality free to take part in its occurrence.89 Truth is

Heidegger book.indb 133 12/11/2013 2:43:15 PM

134 Heidegger and the Work of Art History

composed in the work in the intimacy of the work’s creation and it is for this

reason that all art is essentially poetry. Poetry is ‘projective saying’, it is the

original naming of things and from a world-historic point of view, in being

so composed, the meaning of Being constitutive of an age is ‘materialized’ in

the work.

Work and Thing

The ‘Origin’ essay is not the end of the story for materiality in Heidegger’s

thought. In a sense, it is a beginning. This is because Heidegger will build

on his account of earth/materiality as a groundless ground, that supports by

y

withdrawing (Ab-grund, abyss), in the 1940s in terms of the ‘fourfold’ (Geviert),

the ‘gathering’ of earth and sky, gods and mortals, that is constitutive of

op

‘the thing’.90

In his account of the fourfold, Heidegger focuses on the seemingly

mundane things that surround us in terms that do not subordinate them to

occurrentness or to our pragmatic tasks. The thing, thought in terms of the

fourfold, is not simply ready-to-hand. Nor is it present-at-hand. Heidegger’s

C

examples of things include benches and footbridges, jugs and ploughs, trees

and hills, deer and horses, clasps and books, pictures, crown and cross.91

In short, everything that we meet in our experience may be designated

a ‘thing’ in Heidegger’s sense. The notion of a thing intends to capture the

f

essential ‘relationality of worldly existence’.92 Things allow earth and sky,

gods and mortals to presence in their ‘simple oneness’. As a gathering, the

oo

stability of the thing as a present object is undermined. Things, while they

are culturally paradigmatic, are not everlasting and in ‘thinging’ (working)

the fourfold ‘disaggregates’ or ‘desubstantializes’ the thing: it releases it from

its ‘encapsulated self-identity’ as a discrete object and so allows it to enter a

world as a relational context of significance and involvements.93

Pr

Things extend beyond themselves and the world that we inhabit is a world

constituted by them. Each thing is a collection of relations that reciprocally

determine a world.94 In this context the mundane things that we meet in

our everyday experience – including our everyday experience as a visitor

to a museum – preserve something mysterious. That is, things preserve the

clearing concealing event that marks the mystery of Being itself: das Ereignis.95

Earth and sky, divinities and mortals … belong together by way of the

simpleness of the united fourfold. Each of the four mirrors in its own way the

presence of the others … Mirroring in this appropriating-lightening way, each

of the four plays to each of the others … This appropriating mirror-play of the

simple onefold of earth and sky, divinities and mortals, we call the world.96

Heidegger book.indb 134 12/11/2013 2:43:15 PM

Art, Materiality, and the Meaning of Being 135

In ‘The Thing’, the appropriating mirror-play of the four, names the event of

appropriation, das Ereignis. Things are not ‘in’ a world: they participate in the

originary opening of worlds.

Conclusion

In today’s museums, works of art and things sit side by side and both, on

Heidegger’s account, participate in the opening of historical worlds. Works

of art and things are agents of das Ereignis. By virtue of this connection might

we be able to move beyond an understanding of the museum as mausoleum?

Might we be able to think the museum as a space, not just of difference, but

y

as a space that ‘bids the dif-ference to come[?]’97 If so, the museum would

become a space that holds open the difference between Being and beings

op

and would bid the finite disclosure of Being qua meaningful presence in

conjunction with the opening up of Dasein qua finitude. If so, the museum

would become a space of the origination of meaning in the lives of its visitors

and of the (re-)opening up of historical worlds. The museum would become a

place that brings home the difference between being and beings, a place that

fC

would enable preservation of the mystery: das Ereignis.

Heidegger’s philosophy of art is explosive: true art history is world

historical because reading a work can reveal the way in which things were

meaningful for an epoch. Further, by prompting us to consider ‘the mystery’

of das Ereignis Heidegger’s philosophy of art provokes us to tackle the question

of how these works are going to matter for us now and in the future. Art,

oo

materiality, and the meaning of Being unite in the culturally paradigmatic

work, be that van Gogh’s Pair of Shoes, Rembrandt’s A Man in Armour, a

carved wooden Ceremonial Turtle Post from the Torres Strait, or a painted

cave. 98 Great works of art enshrine the ‘meaning of Being’ constitutive of

an age and art history takes on a world historic dimension insofar as it can

Pr

hermeneutically reconstruct such meanings.

Notes

1 I would like to thank Helen Watkins for her helpful comments on an earlier draft of this paper. I

would like to thank Philip Wallace and William Tonner for their help with this and other projects.

I’m in their debt. Earlier versions of this paper were delivered at the 36th Annual Conference

of The Association of Art Historians held at the University of Glasgow in April 2010 and at the

conference, Transgression and Its Limits, held at the University of Stirling in May 2010. I would

like to thank the organizers of both events.

2 The first version of Heidegger’s ‘Origin of the Work of Art’ lecture was delivered in November

1935 to the Society for the Study of Art in Freiburg/Breisgau. It was delivered a further two

times and was then followed by a three-part series of lectures at the Freie Deutsche Hochstift in

Heidegger book.indb 135 12/11/2013 2:43:15 PM

136 Heidegger and the Work of Art History

Frankfurt/Main towards the end of 1936. The ‘Origin’ essay was first published in Holzwege in 1950

and appeared with revisions and the addition of the addendum as Der Ursprung des Kunstwerkes

in 1960. This version appears as volume 5 of Heidegger’s Gesamtausgabe and is the basis for the

version in both Poetry, Language, Thought and the revised edition of Basic Writings. See Jonathan

Dronsfield, ‘The Work of Art’, in Martin Heidegger: Key Concepts, ed. Bret. W. Davis (Durham:

Acumen, 2009), 163–4, n. 1 and 2.

3 Hubert L. Dreyfus notes that in his marginalia to ‘The Origin of the Work of Art’, Heidegger

‘repeatedly notes’ that what is at stake in this essay is das Ereignis. Hubert L. Dreyfus and Mark A.

Wrathall, ‘Martin Heidegger: An Introduction to His Thought, Work and Life’, in A Companion to

Heidegger, ed. Hubert L. Dreyfus and Mark A. Wrathall (Oxford: Blackwell, 2005), 414.

4 See Thomas Sheehan, ‘Heidegger’, in The World’s Great Philosophers, ed. Robert L. Arrington

(Oxford: Blackwell, 2003), 112; Sheehan, ‘Heidegger, Martin (1889–1976)’, in The Shorter Routledge

Encyclopedia of Philosophy, ed. Edward Craig (London and New York: Routledge, 2005), 362; Philip

Tonner, Heidegger, Metaphysics and the Univocity of Being (London: Continuum 2010), 169; Daniela

Vallega-Neu, ‘Ereignis: The Event of Appropriation’, in Martin Heidegger: Key Concepts, ed. Bret W.

Davis (Durham: Acumen, 2010), 140.

y

5 The abbreviation ‘GA’ refers to the Gesamtausgabe, the collected edition of Heidegger’s works.

6 Charles Guignon, ‘The History of Being’, in A Companion to Heidegger, ed. Hubert L. Dreyfus and

Mark A. Wrathall (Oxford: Blackwell, 2005), 403.

op

7 Tonner, Heidegger, Metaphysics and the Univocity of Being, 140.

8 Thomas E. Wartenberg, ‘Heidegger’, in The Routledge Companion to Aesthetics, ed. Berys Gaut and

Dominic McIver Lopes (London and New York: Routledge, 2001), 154.

9 Martin Heidegger, ‘On the Origin of the Work of Art: First Version’ (1935–1936), in The Heidegger

Reader, ed. Günter Figal, trans. Jerome Veith (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2009).

C

10 Franco-Cantabrian cave art is one of the most notable features of Upper Palaeolithic Europe.

Modern humans arose in Africa between about 200,000–150,000 years ago. From there, Homo

sapiens sapiens dispersed through Arabia and then on to the rest of the world around 60,000

year ago. Their arrival in Europe around 40,000 years ago marks the beginning of the Upper

Palaeolithic period that came to an end at the close of the last Ice Age 10,000 years ago.

11 Bataille’s Prehistoric Painting: Lascaux or the Birth of Art (1955) appeared five years after Heidegger’s

f

‘The Origin of the Work of Art’ essay.

oo

12 Heidegger, ‘The Origin of the Work of Art’, in Poetry, Language, Thought, trans. Albert Hofstadter

(New York: Harper and Row, 1971a), 19.

13 Martin Heidegger, Basic Questions of Philosophy. Selected “Problems” of “Logic.”, Trans. R. Rojcewicz

and A. Schuwer, (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1994). GA volume 45.

14 Guignon, ‘The History of Being’, 393.

15 Ibid., 393.

Pr

16 GA 45, 35.

17 Heidegger, ‘The Origin of the Work of Art’ (1971a), 74.

18 Ibid., 76–7. See also Julian Young, Heidegger’s Philosophy of Art (Cambridge: Cambridge University

Press, 2001), 19.

19 Guignon, ‘The History of Being’, 404.

20 Ibid., 414.

21 See Hubert L. Dreyfus, ‘Heidegger on the Connection between Nihilism, Art, Technology, and

Politics’, in The Cambridge Companion to Heidegger, ed. Charles Guignon (Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press, 1993) and Young, Heidegger’s Philosophy of Art, 18.

22 Bataille’s review of Luquet’s L’Art primitif appears in Documents in 1930: his writings on prehistoric

art and culture represent 30 years of scholarship. The Vézère Valley in the Dordogne is Bataille’s

stand-in for the entirety of prehistory and the jewel in the valley’s crown, the ‘pit of Lascaux’, is a

participant in the moment of the ‘birth of art’.

23 Heidegger, Mindfulness, trans. P. Emad and T. Kalary (London and New York: Continuum 2006), 28.

Heidegger book.indb 136 12/11/2013 2:43:15 PM

Art, Materiality, and the Meaning of Being 137

24 J. Taminiaux, ‘Philosophy of Existence I: Heidegger’, in Continental Philosophy in the 20th Century,

vol. 8, Routledge History of Philosophy, ed. R. Kearney (London and New York: Routledge, 1994), 5.

25 J. Clotte, Cave Art (London: Phaidon, 2008), 22.

26 Heidegger, Mindfulness, 29.

27 Ibid., 29.

28 Young, Heidegger’s Philosophy of Art, 17.

29 Heidegger, Mindfulness, 29.

30 Heidegger, ‘The Origin of the Work of Art’, 1993, 170.

31 Bataille, Tears of Eros, 46.

32 Bataille, Prehistoric Painting: Lascaux; or, The Birth of Art, trans. Austryn Wainhouse (Geneva: Skira,

1955), 18; Suzanne Guerlac, ‘Bataille in Theory: Afterimages (Lascaux)’, Diacritics 26.2 (1996): 10.

33 Guerlac, ‘Bataille in Theory: Afterimages (Lascaux)’, 10–15; Nick Trakakis, ‘Bataille’ in, The

y

Continuum Companion to Continental Philosophy, ed. J. Mullarkey and B. Lord, (London: Continuum,

2009), 283–4. Trakakis, 283.

34 Michel Foucault, ‘A Preface to Transgression’, in Bataille: A Critical Reader, ed. Fred Botting and

35

Scott Wilson (Oxford: Blackwell, 1998), 27.

op

Richard White, ‘Bataille on Lascaux and the Origins of Art’, Janus Head 11.1–2 (2009): 324.

Prohibition has two principle modes: prohibitions to do with sex and prohibitions to do with

death. Regarding sex, Bataille will take from his reading of Levi-Strauss that the transition

from animal to man, from nature to culture, is founded upon the prohibition of incest: here

human beings begin to regulate their lives by means of taboos. See Stuart Kendall, ‘Editor’s

Introduction: The Sediment of the Possible’, in Georges Bataille, The Cradle of Humanity: Prehistoric

fC

Art and Culture, trans. Michelle Kendall and Stuart Kendall, ed. Stuart Kendall (New York: Zone

Books, 2005),12. This ‘forbidden’ is the originating moment of humanity and of ordered society.

Regarding death, Bataille recognizes that his intermediaries between us and the animals, the

Neanderthals, were aware of death and that this is an advance on animals’ ‘indifference to the

dead’. See Georges Bataille, Tears of Eros, 32. Nevertheless, it is with modern man that a ‘new value’

is born: ‘the dead … overawed the living, who made haste to forbid that they be approached …In

raising this barrier of prohibition round what fills him with awe and fascinated terror, man enjoins

all beings and all creatures to respect it: for it is sacred.’ See Bataille, Prehistoric Painting: Lascaux;

oo

or, The Birth of Art, 31. The sacred is that which unifies and binds society together yet it lies at the

very limit of society; the sacred inhabits societies ‘forbidden margins’. See Nick Trakakis, ‘Bataille’,

in The Continuum Companion to Continental Philosophy, ed. John Mullarkey and Beth Lord (London:

Continuum, 2009), 283.

36 Bataille, Prehistoric Painting, 39.

37 Bataille, The Accursed Share: An Essay on General Economy, vol. I, trans. Robert Hurley (New York:

Zone Books, 1989c), 55.

Pr

38 Bataille, Prehistoric Painting, 15.

39 Ibid., 15.

40 Guerlac, ‘Bataille in Theory: Afterimages (Lascaux)’, 10.

41 Bataille, Prehistoric Painting, 7.

42 Young, , Heidegger’s Philosophy of Art, 15

43 Ibid., 15–16.

44 White, ‘Bataille on Lascaux and the Origins of Art’, 329.

45 Doric Temple of Hera II, the ‘Temple of Poseidon’, at Paestum (Lucania) Italy, fifth century BC. See

Sheehan, ‘Heidegger, Martin (1889–1976)’, 365.

46 Bataille, Prehistoric Painting, 27.

47 Heidegger, ‘On the Origin of the Work of Art: First Version’, 149.

48 Heidegger, ‘The Origin of the Work of Art’, 1993, 168.

Heidegger book.indb 137 12/11/2013 2:43:15 PM

138 Heidegger and the Work of Art History

49 Bataille, for his part, accepted the interpretation of Upper Palaeolithic parietal art as sympathetic

magic: the cave paintings’ ‘work’ was to facilitate a successful hunt. See Clotte, Cave Art, 23.

On this view it was the act of painting or engraving that was paramount rather than the work

produced since that work would only be seen by a select few. The art works produced were

intended to ensure the success of the hunt, the killing of dangerous animals (the lions and bears

represented), and the plenty of game. This theory would explain the images of animals that

appear to be wounded. The human and composite creatures might be sorcerers or shamans

dressed in animal skins so as to manifest the qualities of the animal. Alternatively, they may be

representations of a god. Further, somewhat unconvincingly, the geometric signs present in the

caves might represent weapons or traps.

50 In the ‘Holiest of Holies’ of Lascaux in the ‘pit’ (or ‘shaft’ or ‘well’), there is, Bataille argues,

a representation of ritual murder and so the moment of art’s birth is bound up with the

transgression of the taboo on murder. Here represented is a fleeing rhinoceros, a dying humanoid

figure with what appears to be the head of a bird, a wounded bison and what appears to be a

staff with a bird on top. A shaman-executioner with bird mask who is imbued with ‘sacramental

character’ and who recognizes the divinity of the beast slain by him by his own death expiates the

murder of the bison. This panel depicts that primitive form of transgression, the hunt, the moment

of both the appearance of and slaying of the animal; a moment which is ‘at once inevitable and

y

reprehensible’. See Bataille, Eroticism, trans. M. Dalwood (London: Marion Books, 2006), 74.

51 Bataille, Tears of Eros, 50.

op

52 Heidegger, ‘The Origin of the Work of Art’, 1993, 165. See also Wartenberg, ‘Heidegger’, 150.

53 The key terms in Heidegger’s thought – disclosure, emergence, unconcealment, truth, the

meaning of Being – all refer to the same phenomenon: the occurrence of Being within finite

human understanding. Disclosure happens at three levels (starting from the most fundamental to

the least) ‘world-disclosure’, ‘pre-predicative disclosure’, and ‘predicative disclosure’. World-

disclosure is the original opening up of a field of significance (the Da, ‘the there’, the world) for

Dasein (human existence). This opening up of a field of significance allows the beings that we

C

meet in our experience to be meaningfully present to us and for them to be known by us pre-

predicatively (pre-linguistically/pre-conceptually). Here such beings may be used by us within

the various worlds of our practical engagement and concern. Combined, world-disclosure and

the pre-predicative disclosedness qua availability of beings, enables predicative disclosure:

foundational levels of disclosure enable the kind of disclosure present in our conceptual

judgements and comportment towards things and ideas. ‘Truth’ in the sense of correspondence

f

between our ideas and states of affairs operates at this level. This is the level of the traditional

correspondence theory of truth that Heidegger thinks is inadequate, and he argues that the more

oo

profound ‘essence of truth’ qua world-disclosure is what makes such conceptual truth possible.

See Sheehan, ‘Heidegger’, 106–11. The ancient Greek word for truth, aletheia (unconcealedness),

captures Heidegger’s sense of truth and on his account, knowing a being in its truth is to know

that being as what ‘it is’, in its being. See Wartenberg, ‘Heidegger’, 150.

54 Michael Inwood, ‘Art and the Work’, in A Heidegger Dictionary (Oxford: Blackwell, 1999), 18.

55 Dreyfus and Wrathall, ‘Martin Heidegger: An Introduction to His Thought, Work and Life’, in A

Companion to Heidegger, ed. H. L. Dreyfus and M. A. Wrathall (Oxford: Blackwell, 2005), 3.

Pr

56 Ready-to-hand items can become present-at-hand when they become objects of (quasi) scientific

enquiry. For example, a useful tool breaks in mid activity. In this situation the agent’s normally

simple and fluid practical engagement with their useful tool that they use to accomplish their

tasks is interrupted and they encounter a difficulty and an unanticipated situation. The transition

from ready-to-hand equipment to present-at-hand occurrent object transpires when the sheer

occurrentness of the object obtrudes and the object presents itself as a discrete property bearing

entity that needs to be fixed.

57 Heidegger, ‘The Origin of the Work of Art, 1971a, 19.

58 See Inwood, ‘Art and the Work’, 18; see Heidegger, ‘The Origin of the Work of Art, 1971a, 19.

59 Ibid., 19.

60 Heidegger, ‘The Origin of the Work of Art, 1993, 156; Dronsfield, ‘The Work of Art’, 130.

61 Heidegger, ‘The Origin of the Work of Art’, 1971a, 41.

62 Heidegger, ‘The Origin of the Work of Art’, 1993, 168.

63 Ibid., 204.

Heidegger book.indb 138 12/11/2013 2:43:15 PM

Art, Materiality, and the Meaning of Being 139

64 Theodor Adorno, Prisms, trans. Samuel Weber and Shierry Weber (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press,

1967).

65 Heidegger, ‘The Origin of the Work Art’, 1971a, 40; Young, Heidegger’s Philosophy of Art, 19.

66 Young, Heidegger’s Philosophy of Art, 140.

67 Heidegger, Hölderlin’s Hymn ‘The Ister’, trans. William McNeill and Julie Davis (Bloomington:

Indiana University Press, 1996), 35.

68 Young, Heidegger’s Philosophy of Art, 140. Metaphysics qua representational thinking orders beings.

One example of this that Heidegger notes in the 1930s is the medieval doctrine of the analogy

of Being which on his account provides a formula for understanding the being of creatures in

relation to the creating and preserving Being, God. Analogical thinking does not raise the question

of being but rather formulates a religious conviction in metaphysical terms. Heidegger’s response

to this twofold problem is first that conceptual or representational thinking qua metaphysics must

be ‘stepped back’ from. Second, our experience of beings should not be set up in representational

or conceptual terms: that is, one must ‘let beings be.’

69 Heidegger, Nietzsche, vol. 1, The Will to Power as Art, trans. David Farrell Krell (San Francisco:

y

Harper & Row, 1979), 80–82. Artisans establish a form in formless matter and the understanding

of Being accompanying this is genetically related to the productive activity of human agents. See

Tonner, Heidegger, Metaphysics and the Univocity of Being, 41.

70 Heidegger, Nietzsche, 84.

71

72

op

Dronsfield, ‘The Work of Art’, 129. Great art has, since the end of the Middle Ages at the latest,

become a ‘thing of the past’. The greatest period of Western art occurred in eighth- to fourth-

century Greece. By the time of Plato and Aristotle such art was in terminal decline. See Young,

Heidegger’s Philosophy of Art, 1, 6–7, 15.

Heidegger, ‘The Origin of the Work of Art’, 167.

fC

73 Ibid., 161. Italics in the original.

74 Heidegger, ‘The Origin of the Work of Art’, 1971a, 44–5. In his 1987 interruption of the Heidegger-

Schapiro-subjectivism discussion, Derrida suggests that both Heidegger and Schapiro must

presuppose that the shoes in question in Heidegger’s essay are in fact ‘a pair’: for Heidegger, a

pair of peasant shoes; for Schapiro, a pair from the city. See Jacques Derrida, ‘Restitutions of the

Truth in Pointing [Pointure]’, in The Truth in Painting, trans. Geoff Bennington and Ian McLeod

(Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1987), 259. Being ‘a pair’ of shoes is a condition of their

oo

being available to a subject because, firstly, they invoke the subject who can stand in them and who

is ultimately the subject of the painting and, secondly, because the ‘pair-being’ of the shoes is itself

a projection of a subject for whom the painting is an object. As a result, the ‘essential uselessness’

of the painting is transformed into an object with use-value since it serves both Heidegger’s and

Schapiro’s ends, which is the appropriation of the painting at the expense of its work-being. See

Dronsfield, ‘The Work of Art’, 137. Generally, Derrida posits an axiom: ‘the desire for attribution is

a desire for appropriation.’ See Derrida, ‘Restitutions of the Truth in Pointing [Pointure]’, 260.

Pr

75 Heidegger, ‘The Origin of the Work of Art’, 1993, 159–60 (my emphasis).

76 Wartenberg, ‘Heidegger’, 152.

77 Heidegger, Mindfulness, 38–9.

78 Ibid., 28.

79 Heidegger, ‘The Origin of the Work of Art’, 1993, 167.

80 Dreyfus, ‘Heidegger on the Connection between Nihilism, Art, Technology, and Politics’, in The

Cambridge Companion to Heidegger, ed. Charles Guignon (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press,

1993); Young, Heidegger’s Philosophy of Art, 18.

81 Heidegger, ‘The Origin of the Work of Art’, 1993, 170.

82 Ibid., 171.

83 Dronsfield, ‘Philosophies of Art’, 219; Dronsfield, ‘The Work of Art’, 132.

84 Dronsfield, ‘The Work of Art’, 132; Young, Heidegger’s Philosophy of Art, 48. Dronsfield puts it

thus with regard to the temple work: ‘the work of the temple is not just to show things in their

emergence, but to illuminate that in and on which they emerge, to set the world thus opened back

Heidegger book.indb 139 12/11/2013 2:43:15 PM

140 Heidegger and the Work of Art History

again on earth … It is through the ways in which the materials of an artwork are arranged that

the earth’s self-secluding nature is unfolded. It is the excess of its materiality that denies us the

possibility of ever fully mastering the work in our interpretations of it’. See Dronsfield, ‘The Work

of Art’, 132–3.

85 Heidegger, ‘The Origin of the Work of Art’, 1993, 188.

86 Ibid., 189.

87 Andrew Mitchell, ‘The Fourfold’, in Martin Heidegger: Key Concepts, ed. B.W. Davis (Durham:

Acumen, 2010), 209.

88 Heidegger, ‘The Origin of the Work of Art’, 1993, 189.

89 Dronsfield, ‘The Work of Art’, 134.

90 The fourfold was named by Heidegger in 1949, the year his teaching ban was lifted, in the lecture

series ‘Insight Into That Which Is’ that he delivered at the private Club Zu Bremen. References

occur to the fourfold from the 1940s to the 1970s (Mitchell, ‘The Fourfold’, 2010, 208–18).

y

91 Heidegger, ‘The Thing’, in Poetry, Language, Thought, trans. A. Hofstadter (New York: Harper &

Row, 1971b), 182.

92 Mitchell, ‘The Fourfold’, 208.

op

93 Ibid., 209–10.

94 Ibid., 208.

95 Vallega-Neu, ‘Ereignis: The Event of Appropriation’, 148.

96 Heidegger, ‘The Thing’, 179.

97 Heidegger, ‘Language’, in Poetry, Language, Thought, trans. Albert Hofstadter (New York: Harper

C

& Row, 1971c), 210. (Square brackets, my addition.) Foucault suggests an interpretation of the

museum as a ‘space of difference’ where the elements and relations constitutive of a culture

are ‘suspended, neutralized, or reversed’. See Beth Lord, ‘Foucault’s Museum: Difference,

Representation, and Genealogy’, in Museum and Society 4.1 (March 2006): 1.

98 The only two remaining examples of such posts are now on display in Kelvingrove Museum and

f

Art Gallery in Glasgow, Scotland.

oo

Pr

Heidegger book.indb 140 12/11/2013 2:43:15 PM

You might also like

- Tom Gunning - What's The Point of An IndexDocument12 pagesTom Gunning - What's The Point of An IndexJu Simoes100% (1)

- 1989 Buchloh Benjaim (Interview With Jean-Hubert Martin), The Whole Earth Show, Art in America, Vol. 77, No. 5, May, Pp. 150-9, 211, 213Document12 pages1989 Buchloh Benjaim (Interview With Jean-Hubert Martin), The Whole Earth Show, Art in America, Vol. 77, No. 5, May, Pp. 150-9, 211, 213Iván D. Marifil MartinezNo ratings yet

- (Studies in Literature and Science) Michel Serres, Genevieve James, James Nielson-Genesis - University of Michigan Press (1995)Document154 pages(Studies in Literature and Science) Michel Serres, Genevieve James, James Nielson-Genesis - University of Michigan Press (1995)OneirmosNo ratings yet

- Art of The Digital Age by Bruce Wands PDFDocument2 pagesArt of The Digital Age by Bruce Wands PDFvstrohmeNo ratings yet

- Wolfgang Tillmans - NoticeDocument74 pagesWolfgang Tillmans - NoticeSusana Vilas-BoasNo ratings yet

- Bloch 1974 - Duchamp's Green BoxDocument6 pagesBloch 1974 - Duchamp's Green Boxmanuel arturo abreuNo ratings yet

- Sternberg Press - January 2018Document7 pagesSternberg Press - January 2018ArtdataNo ratings yet

- Video Installation Art: The Body, The Image, and The Space-in-BetweenDocument14 pagesVideo Installation Art: The Body, The Image, and The Space-in-BetweenAnonymous qBWLnoqBNo ratings yet

- The Object as a Process: Essays Situating Artistic PracticeFrom EverandThe Object as a Process: Essays Situating Artistic PracticeNo ratings yet

- Si-Te-Cah Oral History and Archaeological FindingsDocument3 pagesSi-Te-Cah Oral History and Archaeological FindingsHugo F. Garcia ChavarinNo ratings yet

- Braudel's Historiography ReconsideredDocument139 pagesBraudel's Historiography Reconsideredmar1afNo ratings yet

- England Will BurnDocument260 pagesEngland Will Burnulisses gomes do pradoNo ratings yet

- Objects in Air: Artworks and Their Outside around 1900From EverandObjects in Air: Artworks and Their Outside around 1900No ratings yet

- Richard SerraDocument13 pagesRichard SerraJérôme Dechaud100% (1)

- The Violence of Public Art - Do The Right Thing - MitchellDocument21 pagesThe Violence of Public Art - Do The Right Thing - MitchellDaniel Rockn-RollaNo ratings yet

- Boris GroysDocument9 pagesBoris GroysStanislav BenderNo ratings yet

- Seven Days in The Art World - Art BooksDocument4 pagesSeven Days in The Art World - Art BookshuxoduhaNo ratings yet

- Anthropology, Photography PDFDocument14 pagesAnthropology, Photography PDFIgnacio Fernández De MataNo ratings yet

- Pierre Huyghe. Les Grands: Ensembles, 2001. VistavisionDocument24 pagesPierre Huyghe. Les Grands: Ensembles, 2001. Vistavisiontemporarysite_orgNo ratings yet

- Godfrey, Mark - The Artist As HistorianDocument35 pagesGodfrey, Mark - The Artist As HistorianDaniel Tercer MundoNo ratings yet

- Gerhard Richter's Photo-Paintings Address Photography's Impact on PaintingDocument13 pagesGerhard Richter's Photo-Paintings Address Photography's Impact on PaintingCafeRoyalNo ratings yet

- Art and Archive 1920-2010Document18 pagesArt and Archive 1920-2010Mosor VladNo ratings yet

- Michael Newman 'Fiona Tan: The Changeling' (2009)Document6 pagesMichael Newman 'Fiona Tan: The Changeling' (2009)mnewman14672No ratings yet

- Influential Theorists: Andre Bazin - The Ontology of The Photographic Image - The Motley ViewDocument8 pagesInfluential Theorists: Andre Bazin - The Ontology of The Photographic Image - The Motley ViewJasmine J. WilsonNo ratings yet

- The Arts of Looking PDFDocument10 pagesThe Arts of Looking PDFRoberto García AguilarNo ratings yet

- Literature & Theology Vol. 27 No. 4 Optical UnconsciousDocument15 pagesLiterature & Theology Vol. 27 No. 4 Optical UnconsciousDana KiosaNo ratings yet

- A Brief Genealogy of Social Sculpture (2010)Document21 pagesA Brief Genealogy of Social Sculpture (2010)Alan W. MooreNo ratings yet

- Photographs and Memories PDFDocument36 pagesPhotographs and Memories PDFmentalpapyrusNo ratings yet

- Contemporary Art in The AnthropoceneDocument83 pagesContemporary Art in The AnthropoceneMk YurttasNo ratings yet

- Quentin Bajac - Age of DistractionDocument12 pagesQuentin Bajac - Age of DistractionAlexandra G AlexNo ratings yet

- Notes On The Demise and Persistence of Judgment (William Wood)Document16 pagesNotes On The Demise and Persistence of Judgment (William Wood)Azzad Diah Ahmad ZabidiNo ratings yet

- BirnbaumDocument9 pagesBirnbaumJamieNo ratings yet

- Semiotics and Western Painting: An Economy of SignsDocument4 pagesSemiotics and Western Painting: An Economy of SignsKavya KashyapNo ratings yet

- The Sophist An The Photograph Olivier RichonDocument6 pagesThe Sophist An The Photograph Olivier RichonDawnaNo ratings yet

- Foster - Hal - Primitve Unconscious of Modern ArtDocument27 pagesFoster - Hal - Primitve Unconscious of Modern ArtEdsonCosta87No ratings yet

- Truth of PhotoDocument117 pagesTruth of PhotoLeon100% (1)

- Piero Manzoni 1Document12 pagesPiero Manzoni 1Karina Alvarado MattesonNo ratings yet

- 6 Modes of Documentaries Task 5Document8 pages6 Modes of Documentaries Task 5Ras GillNo ratings yet

- Maccarone Ethical Responsibility and DocumentariesDocument17 pagesMaccarone Ethical Responsibility and DocumentariesPaulina Albornoz AlvaradoNo ratings yet

- Reset Modernity GB PDFDocument74 pagesReset Modernity GB PDFChristopher HoltzNo ratings yet

- Branden-W-Joseph-RAUSCHENBERG White-on-White PDFDocument33 pagesBranden-W-Joseph-RAUSCHENBERG White-on-White PDFjpperNo ratings yet

- Sternberg Press - October 2017Document6 pagesSternberg Press - October 2017ArtdataNo ratings yet

- Carol Duncan - The Problematics of Collecting and Display, Part 1 PDFDocument20 pagesCarol Duncan - The Problematics of Collecting and Display, Part 1 PDFPatrick ThuerNo ratings yet

- Photography - HistoryDocument27 pagesPhotography - HistoryMiguelVinci100% (1)

- Chapter 4 (FINAL)Document29 pagesChapter 4 (FINAL)Vittoria DaelliNo ratings yet

- Groys The Curator As Iconoclast 2007Document9 pagesGroys The Curator As Iconoclast 2007Virginia Lazaro VillaNo ratings yet

- Ruscha (About) WORDSDocument5 pagesRuscha (About) WORDSarrgggNo ratings yet

- Sternberg Press - January 2020Document14 pagesSternberg Press - January 2020ArtdataNo ratings yet

- Animalisms: Jan Verwoert Explores Connections Between Art, Emotion and NatureDocument9 pagesAnimalisms: Jan Verwoert Explores Connections Between Art, Emotion and NatureJeezaNo ratings yet

- Coco Fusco On Chris OfiliDocument7 pagesCoco Fusco On Chris OfiliAutumn Veggiemonster WallaceNo ratings yet

- Allan Sekula - War Without BodiesDocument6 pagesAllan Sekula - War Without BodiesjuguerrNo ratings yet

- Kitchin and Dodge - Rethinking MapsDocument15 pagesKitchin and Dodge - Rethinking MapsAna Sánchez Trolliet100% (1)

- Le Feuvre Camila SposatiDocument8 pagesLe Feuvre Camila SposatikatburnerNo ratings yet

- Bourriaud PostproductionDocument47 pagesBourriaud Postproductionescurridizo20No ratings yet

- The Mirror in Art: Vanitas Veritas and VisionDocument40 pagesThe Mirror in Art: Vanitas Veritas and Visionthoushaltnot100% (2)

- October's PostmodernismDocument12 pagesOctober's PostmodernismDàidalos100% (1)

- The Post-Medium Condition and The Explosion of Cinema Ji-Hoon KimDocument10 pagesThe Post-Medium Condition and The Explosion of Cinema Ji-Hoon KimtorbennutsNo ratings yet

- Hal Foster Reviews Ways of Curating' by Hans Ulrich Obrist and Curationism' by David Balzer LRB 4 June 2015Document4 pagesHal Foster Reviews Ways of Curating' by Hans Ulrich Obrist and Curationism' by David Balzer LRB 4 June 2015Azzad Diah Ahmad ZabidiNo ratings yet

- Physicality of Picturing... Richard ShiffDocument18 pagesPhysicality of Picturing... Richard Shiffro77manaNo ratings yet

- Wages Against ArtworkDocument52 pagesWages Against ArtworkNina Hoechtl100% (1)

- A Cinema in The Gallery, A Cinema in Ruins: ErikabalsomDocument17 pagesA Cinema in The Gallery, A Cinema in Ruins: ErikabalsomD. E.No ratings yet

- Softsculptureevents - MEKE SKULPTURE VAOOO PDFDocument28 pagesSoftsculptureevents - MEKE SKULPTURE VAOOO PDFadinaNo ratings yet

- Serres - Science and The Humanities - The Case of TurnerDocument17 pagesSerres - Science and The Humanities - The Case of TurnerHansNo ratings yet

- Being Singular Plural (Nancy)Document57 pagesBeing Singular Plural (Nancy)kegomaticbot420100% (1)

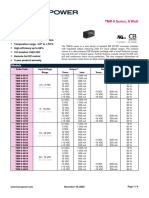

- tmr6 DatasheetDocument4 pagestmr6 DatasheetHansNo ratings yet