Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Prevenir Sob en Infantes. Pediatrics 2016

Uploaded by

nadiaCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Prevenir Sob en Infantes. Pediatrics 2016

Uploaded by

nadiaCopyright:

Available Formats

Preventing Exacerbations in

Preschoolers With Recurrent

Wheeze: A Meta-analysis

Sunitha V. Kaiser, MD, MSc,a Tram Huynh,b Leonard B. Bacharier, MD,c Jennifer L. Rosenthal, MD,

d Leigh Anne Bakel, MD,e Patricia C. Parkin, MD, FRCPC,f Michael D. Cabana, MD, MPHa,g,h

CONTEXT: Half of children experience wheezing by age 6 years, and optimal strategies for abstract

preventing severe exacerbations are not well defined.

OBJECTIVE: Synthesize the evidence of the effects of daily inhaled corticosteroids (ICS),

intermittent ICS, and montelukast in preventing severe exacerbations among preschool

children with recurrent wheeze.

DATA SOURCES: Medline (1946, 2/25/15), Embase (1947, 2/25/15), CENTRAL.

STUDY SELECTION: Studies were included based on design (randomized controlled trials),

population (children ≤6 years with asthma or recurrent wheeze), intervention and

comparison (daily ICS vs placebo, intermittent ICS vs placebo, daily ICS vs intermittent ICS,

ICS vs montelukast), and outcome (exacerbations necessitating systemic steroids).

DATA EXTRACTION: Completed by 2 independent reviewers.

RESULTS: Twenty-two studies (N = 4550) were included. Fifteen studies (N = 3278) compared

daily ICS with placebo and showed reduced exacerbations with daily medium-dose ICS (risk

ratio [RR] 0.70; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.61–0.79; NNT = 9). Subgroup analysis of

children with persistent asthma showed reduced exacerbations with daily ICS compared

with placebo (8 studies, N = 2505; RR 0.56; 95% CI, 0.46–0.70; NNT = 11) and daily ICS

compared with montelukast (1 study, N = 202; RR 0.59; 95% CI, 0.38–0.92). Subgroup

analysis of children with intermittent asthma or viral-triggered wheezing showed reduced

exacerbations with preemptive high-dose intermittent ICS compared with placebo

(5 studies, N = 422; RR 0.65; 95% CI, 0.51–0.81; NNT = 6).

LIMITATIONS: More studies are needed that directly compare these strategies.

CONCLUSIONS: There is strong evidence to support daily ICS for preventing exacerbations in

preschool children with recurrent wheeze, specifically in children with persistent asthma.

For preschool children with intermittent asthma or viral-triggered wheezing, there is strong

evidence to support intermittent ICS for preventing exacerbations.

aDepartment of Pediatrics, gPhillip Lee Institute for Health Policy Studies, and hDepartment of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, University of California, San Francisco, California; bSchool of

Public Health, University of California, Berkeley, California; cDepartment of Pediatrics, Washington University School of Medicine, St Louis, Missouri; dDepartment of Pediatrics, University of

California, Davis, California; eDepartment of Pediatrics, University of Colorado, Denver, Colorado; and fDepartment of Paediatrics, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada

Dr Kaiser conceptualized and designed the study, performed the systematic review and meta-analysis, drafted the initial manuscript, and reviewed and revised

the manuscript; Ms Huynh and Dr Rosenthal performed the systematic review and critically reviewed the manuscript; Drs Bacharier, Bakel, Parkin, and Cabana

conceptualized and designed the study, performed the systematic review, and critically reviewed the manuscript; and all authors approved the final manuscript as

submitted.

To cite: Kaiser SV, Huynh T, Bacharier LB, et al. Preventing Exacerbations in Preschoolers With Recurrent Wheeze: A Meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 2016;137(6):e20154496

Downloaded from by guest on March 7, 2017

PEDIATRICS Volume 137, number 6, June 2016:e20154496 REVIEW ARTICLE

Half of all children experience one to health care providers and Literature Search

or more episodes of wheezing by 6 caregivers by mitigating the burden

In consultation with a medical

years of age,1 and these wheezing and risks of daily ICS. The more

librarian, we created search

episodes lead to substantial recent 2015 Global Initiative for

strategies for 3 databases (Medline,

morbidity, caregiver burden, and Asthma guideline, which integrates

Embase, and CENTRAL) from

health care costs.2 In the United these recent studies, recommends

inception to February 2015.

States, annual direct health care costs considering intermittent ICS for

The detailed search strategy for

due to asthma in children exceed $50 preschool children with EVW.11

Medline and Embase is outlined

billion,3 and rates of asthma-related

in the Supplemental Appendix.

emergency department visits and Because of the complexity of Briefly, the search used terms for

hospitalizations are highest among managing preschool children with glucocorticoids (glucocorticoid/ and

preschool children.4 recurrent wheeze, substantial detailed listing of all indexed drugs

Optimal strategies for preventing practice variation exists regarding within the glucocorticoid category),

severe asthma exacerbations in this choice of therapy for preventing montelukast, asthma (asthma/ or

population are not well defined. The severe exacerbations.12 Given status asthmaticus/ or asthma* or

2007 National Asthma Education the magnitude of disease burden reactive adj2 airway* or wheez*), and

and Prevention Program guidelines and health care costs of recurrent inhaled (inhalational or nebulizer/

recommend that preschool wheezing in preschoolers, it is or vaporizer/ or inhaler/ and related

children be classified in terms of paramount that we determine the terms), limited to studies of humans

asthma severity, and for those with optimal therapeutic strategy for and children. We also searched

persistent asthma, daily inhaled preventing severe exacerbations in abstracts of the Pediatric Academic

corticosteroids (ICS) be initiated to these children. The primary objective Societies (2002–2014) and American

prevent severe exacerbations.5 Daily of this systemic review and meta- Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and

ICS have been shown to significantly analysis is to synthesize the evidence Immunology conference proceedings

reduce exacerbations in preschool of the effects of daily ICS, intermittent (1996–2015), reference lists of all

children, especially those with ICS, and montelukast as strategies included papers and relevant reviews

persistent symptoms.6 However, for preventing severe exacerbations identified, and the top 200 citations

there are concerns about effects in preschool children with recurrent from Google Scholar (using terms

on linear growth with prolonged wheeze. Our secondary objective “asthma,” “wheeze,” “child,” “steroid,”

treatment,5 and ICS do not modify the is to synthesize the evidence of the and “montelukast”).

development of asthma or improve effects of these preventive strategies

lung function after discontinuation.7 in specific phenotypes of preschool Study Inclusion Criteria

children with recurrent wheeze. Our

The majority of preschool children work is intended to update and build Studies were considered eligible

with recurrent wheezing have on a recent review of the diagnosis, for inclusion if they met criteria

intermittent, but sometimes severe, management, and prognosis of regarding population, intervention

exacerbations triggered by viral preschool wheeze by Ducharme and comparator, outcomes, and

upper respiratory tract infections et al.13 These data should assist all study design. Participants were

(URTIs) and minimal symptoms practitioners who provide primary children ages ≤6 years with asthma

between exacerbations.1 This care to young children, provide or recurrent wheezing (≥2 episodes

pattern of illness has been called subspecialty care to children with in last year). Studies that included

episodic viral wheeze (EVW)8 or recurrent wheezing, and provide only children <2 years were excluded

severe intermittent wheezing.9 care for children during acute because of the potential overlap with

Although wheezing patterns and exacerbations. bronchiolitis in this age group.15,16

phenotypes in young children can We included studies comparing the

change over a short time,10 recent following interventions: daily ICS

studies have examined phenotype- versus placebo, intermittent ICS

directed strategies for preventing METHODS versus placebo, daily ICS versus

severe exacerbations, as well as intermittent ICS, or any regimen

alternative strategies to daily ICS. We conducted and reported this of ICS versus any regimen of

Two alternative strategies include systematic review in accordance montelukast. We included any studies

intermittent (started at the onset with the Preferred Reporting Items that reported on our outcome: severe

of URTI) ICS and the leukotriene for Systematic Reviews and Meta- wheezing exacerbations necessitating

inhibitor montelukast. Both of these Analyses statement.14 We did not systemic (oral or intravenous)

strategies offer potential advantages register a protocol. corticosteroid. Severe exacerbations

Downloaded from by guest on March 7, 2017

2 KAISER et al

studies for risks of bias in selection,

performance, detection, attrition,

or reporting.18 This process was

not blinded to manuscript origin.

Study quality assessments were

incorporated into a sensitivity

analysis and the final conclusions.

Measures of Treatment Effect

For rates of severe wheezing

exacerbations necessitating systemic

steroids, we collected numbers of

participants in each group with

and without the outcome and

determined pooled risk ratios (RRs)

with 95% confidence intervals

(CIs). To determine whether to

pool results, we assessed for

clinical heterogeneity by detailed

consideration of each study (design,

patient characteristics, intervention,

comparison, outcomes, and conduct

of study) and assessed statistical

heterogeneity by visual inspection

of forest plots and calculation of

Cochran’s χ2 test of homogeneity

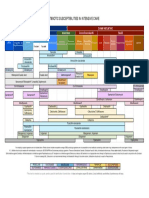

FIGURE 1 and I2 test statistic. A fixed-effects

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses 2009 flow diagram. model was used for the meta-analysis

unless statistical heterogeneity was

were chosen as our primary outcome on inclusion were referred to a third identified (Cochran’s χ2 test P ≤ .05

because they are a patient-important review author. The Supplemental or I2 ≥50%). Analyses were done in

outcome that have significant Appendix includes studies that were Review Manager 5.3 (Copenhagen,

consequences for children, caregivers, excluded, and Fig 1 outlines the study Denmark). Publication bias was

and the health care system.17 Only selection process. assessed with funnel plots.

randomized controlled trials (RCTs)

were included. Guidelines, reviews, Data Extraction and Management Subgroup and Sensitivity Analyses

commentaries, abstracts, and letters Data were extracted via a standardized

to editors were reviewed to identify To determine the efficacy of daily ICS,

data extraction form. Study design, intermittent ICS, and montelukast

any primary data; however, these patient characteristics (age, gender,

publication types were not included for specific phenotypes of preschool

atopy, family history), intervention wheeze, we performed subgroup

because of lack of peer review and (dose, frequency, duration),

inability to judge bias. analyses. Descriptions of each study

intervention and comparator groups, population’s baseline symptoms

methodological quality, and key were carefully reviewed to determine

Study Selection Process outcomes were noted. Corresponding phenotypic classification. We

All titles and abstracts were pooled authors were contacted for information performed 1 subgroup analysis

in EndNote (Thompson Reuters, not available in the journal article. This restricted to studies that described

Philadelphia, PA), and duplicates process was not blinded to manuscript inclusion only of children with

were deleted. Two review authors origin (journal, authors, institution). persistent asthma (symptoms >2

independently screened all titles days/week, nighttime awakenings

Assessment of Risk of Bias in

and abstracts to assess which 1–2/month, short acting β-agonist

Included Studies

studies met the inclusion criteria. use >2 days/week, or minor

We retrieved full-text copies of all Methodological quality of all studies limitation with normal activity).5

potentially relevant articles for was assessed with the Cochrane We performed another subgroup

review. Unresolved disagreements Risk of Bias tool, which assesses analysis that described inclusion

Downloaded from by guest on March 7, 2017

PEDIATRICS Volume 137, number 6, June 2016 3

only of children with intermittent durations ranged from 6 weeks compared daily ICS (budesonide 0.5

asthma (symptoms ≤2 days/week, to 5 years, with most 12 weeks. mg BID) with daily montelukast (4

no nighttime awakenings, short Eight of 15 studies focused on mg daily) over 52 weeks in children

acting β-agonist use ≤2 days/week, preschool children with persistent with persistent asthma.

and no limitation with normal asthma.20–22,24,28, 31,32,35 Only 1 study

activity)5 or viral-triggered wheezing examined daily ICS for children Risk of Bias and Quality

and minimal symptoms between with intermittent asthma or viral- The risk of bias in all included studies

exacerbations (EVW or severe triggered wheeze.37 A funnel plot is illustrated in Fig 2. Twelve of 22

intermittent wheezing). Studies in of these studies was symmetric, studies had low risk of bias. The

which the phenotypes of included suggesting no evidence of publication most common area of concern was

children were mixed or unclear were bias. attrition bias due to incomplete

analyzed as a separate subgroup. We Six studies compared intermittent outcome data. Studies with >20%

also performed a sensitivity analyses ICS with placebo.19,23,27, 30,33,38 loss to follow-up were rated as high

in which we excluded studies with All of these studies were double-blind risk.19,25,27–29, 34,36,38,39 Most studies

high risk of bias in ≥1 domain or RCTs. Two had a crossover did not describe how they handled

crossover design to determine design: Connett and Lenney23 missing data. Szefler et al34 was

whether effect size and direction was (participants switched treatment rated high risk of performance and

consistent with our primary analysis. arms after each URTI) and Wilson detection bias because of open-label

and Silverman38 (participants design. Wilson and Silverman38 was

switched treatment arms after 2 rated high risk because of potential

RESULTS confounding bias, because 13/24

URTIs). The studies used several

different delivery systems and types participants were on daily controller

Description of Studies

of ICS at high dosages (budesonide therapy during the study, which

Results of Search 1.6–2 mg/day, fluticasone 1.5 mg/day, could include ICS.

Our search identified 4290 beclomethasone 2.3 mg/day).

Study durations ranged from

Outcomes

references. After removing duplicates

and screening abstracts, we selected 12 to 52 weeks. Five studies Risk of Severe Wheezing Exacerbations

123 for full-text review. Of these, 101 focused on preschool children Necessitating Systemic Steroids

were excluded upon full-text review. with intermittent asthma or viral- Our meta-analyses of strategies for

Reasons for exclusion are described triggered wheeze.19,23, 27,33,38 A funnel preventing severe exacerbations in

in the Supplemental Appendix. plot of these studies was symmetric, preschool children with recurrent

Twenty-two studies met inclusion suggesting no evidence of publication wheeze are described in Fig 3.

criteria; all were included in the bias. Data from 15 studies (N = 3278)

quantitative synthesis and meta- Two studies directly compared daily showed a significant reduction in

analysis (Fig 1).7,19–39 ICS with intermittent ICS.30,39 Both rates of exacerbations with daily

were double-blind RCTs with parallel ICS compared with placebo (12.9%

Included Studies

designs. Papi et al30 compared high- and 24.0%, respectively; RR 0.70;

Characteristics of included studies dose daily (0.4 mg twice daily [BID]) 95% CI, 0.61–0.79; P < .001; I2 =

are described in Table 1. or intermittent beclomethasone 42%). Treatment of 9 children

(0.8 mg as needed) to placebo for with daily ICS prevented 1 child

Fifteen studies compared daily ICS

12 weeks. Zeiger et al39 compared from experiencing an exacerbation

with placebo.7,20–22, 24–26, 28–32,35–37

high-dose daily (0.5 mg daily) with (number needed to treat [NNT] =

All were double-blind RCTs. Thirteen

intermittent budesonide (1 mg 9; 95% CI, 7–12).

studies had a parallel design, and

2 had crossover designs: Gleeson BID) for 52 weeks in children with Data from 6 studies (N = 588)

and Price28 and Webb et al36 viral-triggered asthma and positive showed a significant reduction

(3-week washout period and no modified asthma predictive index.40 in rates of severe exacerbations

washout, respectively). The studies Two studies compared ICS with with intermittent ICS compared

used several different delivery montelukast.19,34 Both were RCTs with placebo (24.8% and 41.6%,

systems and types of ICS, with most with parallel design. Bacharier respectively; RR 0.64; 95% CI, 0.51–

studies using medium daily doses et al19 compared intermittent 0.81; P < .001; I2 = 0%). Treatment

(budesonide 0.4 mg/day, fluticasone ICS (budesonide 1 mg BID) with of 6 children with intermittent ICS

0.2 mg/day, beclomethasone 0.15 intermittent montelukast (4 mg therapy prevented 1 child from

mg/day, ciclesonide 0.16 mg/day, daily) over 52 weeks in children with experiencing an exacerbation

flucinolide 40 μg/kg/day). Study intermittent wheezing. Szefler et al34 (NNT = 6; 95% CI, 4–11).

Downloaded from by guest on March 7, 2017

4 KAISER et al

TABLE 1 Characteristics of Included Studies

Study Population Intervention (Dose Comparisons (Dose Study Outcomes

Category) Category) Duration

Bacharier et al Children 12–59 mo Intermittent ICS: 1) Intermittent 52 wk Primary outcome: SFDs (mean percentage):

2008 (parallel with intermittent budesonide 1 mg BID montelukast: intermittent ICS (76%), intermittent montelukast

RCT) asthma/EVW; mean via nebulizer (high) 4 mg daily × 7 d (73%), placebo (74%)

age 36 mo, 65% × 7 d started at first started at first

male, 34% with sign of URTI sign of a URTI

eczema, 45% with 2) Placebo Proportion of children with exacerbations:

parental asthma intermittent ICS (38.5%), intermittent

montelukast (46.8%), placebo (55.3%)

Change in height from baseline (cm): intermittent

ICS (7.8), intermittent montelukast (7.9), placebo

(7.5)

Bisgaard et al Children 12–47 mo Daily ICS: 2 doses Placebo 12 wk Primary outcome: mean increase in percentage of

1999 (parallel with persistent fluticasone cough-free days compared with placebo- 0.05 mg

RCT) asthma; mean age suspension via MDI, dose (8%), 0.1 mg dose (12%)

28 mo, 66% male, mask, and spacer Proportion of children with exacerbation: daily ICS

42% with eczema, used: 1) 0.05 mg BID (5%), placebo (16%)

72% with family (low), 2) 0.1 mg BID

history of asthma (medium)

Brand et al 2011 Children ages Daily ICS: 3 doses Placebo 24 wk Primary outcome: proportion of children with

(parallel RCT) 24–72 mo with ciclesonide via exacerbations: 40 μg (4.4%), 80 μg (7.3%), 160 μg

persistent asthma nebulizer used: 1) 40 (6.7%), placebo (10.2%)

and positive API, μg QHS (low), 2) 80

median age 48 mo, μg QHS (low), 3) 160

63% male μg QHS (medium)

Carlsen et al Children age 12–47 Daily ICS: fluticasone Placebo 12 wk Primary outcome: SFDs (mean percentage): daily

2005 (parallel mo with mild suspension 0.1 mg ICS (33%), placebo (20%)

RCT) persistent asthma, BID via pMDI/mask/ Proportion of children with exacerbations: daily ICS

mean age 28 mo, spacer (medium) (6%), placebo (12%)

68% male, 56%

with family history

of asthma

Connett and Children ages Intermittent ICS: Placebo 26 wk Primary outcome: mean symptom score (daytime

Lenney 1993 12–60 mo with budesonide solution wheeze): intermittent ICS (0.69), placebo (0.97),

(crossover intermittent 0.8 mg BID (high) P < .05

RCT) asthma/EVW; 56% via Nebuhaler or 1.6 Proportion of children with exacerbations:

male, 48% with mg BID (high) via intermittent ICS (8%), placebo (32%)

family history of Nebuhaler with mask

atopy × 7 d started at first

sign of URTI

Connett et al Children 12–36 mo Daily ICS: budesonide Placebo 26 wk Primary outcome: mean change in nighttime cough

1993 (parallel with persistent solution 0.2 mg symptom score: daily (−0.4), placebo (+0.1), P

RCT) asthma; mean age BID via Nebuhaler < .05

22 mo, 65% male, (medium) SFDs (mean percentage): daily (54%), placebo

58% with family (31%), P < .0001

history of asthma

de Benedictis Children ages 4–32 Daily ICS: flucinolide Placebo 12 wk Proportion of children with exacerbations: daily

et al 1996 mo, mean age 14 20 μg/kg BID via (62%), placebo (66%)

(parallel RCT) mo, 74% male, 18% nebulizer

with eczema

de Blic et al 1996 Children 6–30 mo, Daily ICS: budesonide 1 Placebo 12 wk Primary outcome: proportion of children with

(parallel RCT) mean age 17 mo, mg BID via nebulizer exacerbations: daily ICS (40%), placebo (83%)

87% male, 47% (high)

with parental

atopy

Downloaded from by guest on March 7, 2017

PEDIATRICS Volume 137, number 6, June 2016 5

TABLE 1 Continued

Study Population Intervention (Dose Comparisons (Dose Study Outcomes

Category) Category) Duration

Ducharme et al Children 12–72 mo Intermittent ICS: Placebo 52 wk Primary outcome: proportion of children with

2009 (parallel with intermittent fluticasone exacerbations: intermittent ICS (39%), placebo

RCT) asthma/EVW; mean suspension 0.75 mg (64%)

age 32 mo, 60% BID (high) via mask/ Mean change in height from baseline (cm):

male, 43% with spacer started at intermittent ICS (6.23 ± 2.62), placebo (6.56 ±

eczema, 47% with first sign of URTI and 2.90), NS

family history of stopped after 48 h

asthma without symptoms

Gleeson and Children 24–72 mo Daily ICS: budesonide Placebo 6 wk in Primary outcome: mean change in peak expiratory

Price 1988 with persistent solution 0.2 mg each arm flow: daily ICS (112%), placebo (101%), P < .05

(crossover asthma; median BID via Nebuhaler (crossover) Proportion of children with exacerbations: daily

RCT) age 51 mo; 67% (medium) (2.6%), placebo (10.3%)

male, 38% with

asthma

Guilbert et al Children 24–36 mo Daily ICS: fluticasone Placebo 104 wk Primary outcome: SFDs (mean percentage): daily

2006 (parallel with positive API; suspension 88 μg BID (93%), placebo (88%), P = .006

RCT) mean age 36 mo, via MDI with mask/ Proportion of children with exacerbations: daily

62% male, 54% spacer (medium) (60%), placebo (65%)

with eczema, 65% Change in height: daily (12.6 cm), placebo (13.7 cm)

with parental

history of asthma

Murray et al Children ages 6–60 Daily ICS: fluticasone Placebo 260 wk Primary outcome: prevalence of asthma at 5 y of

2006 (parallel mo, mean age 22 suspension 0.1 mg age: daily ICS (61%), placebo (64%), P = .68

RCT) mo, 65% male, BID via MDI (medium) Proportion of children with exacerbations: daily ICS

47% with maternal (15.8%), placebo (14.1%)

asthma Change in height z score at 5 y: daily ICS (0.002),

placebo (0.066), P = .501

Papi et al 2009 Children 12–28 mo Daily ICS: 1) Intermittent ICS: 12 wk Primary outcome: SFDs (mean percentage): daily

(parallel RCT) recruited during beclomethasone 0.4 beclomethasone (69.6%), intermittent (64.9%), placebo (61.0)

acute wheezing mg BID via nebulizer 0.8 mg (high) Proportion of children with exacerbations: daily

exacerbation (high) and salbutamol (1.8%), intermittent (5.5%), placebo (9%)

during URTI; mean 1.6 mg PRN via

age 28 mo, 60% nebulizer during

male exacerbation; 2)

Placebo

Qaqundah et al Children age 12–48 Daily ICS: fluticasone Placebo 12 wk Primary outcome: percentage change in daily

2006 (parallel mo with persistent suspension 88 μg BID asthma symptom score: daily (−53.9%), placebo

RCT) asthma; mean age via MDI with mask/ (−44.1%), P = .036

30 mo, 62% male spacer (medium) Proportion of children with exacerbations: daily

(5%), placebo (12%)

SFDs (mean percentage): daily (36%), placebo (36%)

Roorda et al Children ages 12–47 Daily ICS: fluticasone Placebo 12 wk Primary outcome: SFDs (mean percentage): daily

2001 (parallel mo with persistent suspension 0.1 mg ICS (54%), placebo (36%)

RCT) asthma; mean age BID via mask/spacer proportion of children with exacerbations: daily ICS

29 mo, 66% male, (medium) (25%), placebo (36%)

47% with eczema,

71% with family

history of asthma

Svedmyr et al Children 12–36 mo Intermittent ICS: Placebo 52 wk Primary outcome: mean symptom score:

1999 (parallel with intermittent budesonide solution intermittent ICS (0.38 ± 0.21), placebo (0.55 ±

RCT) asthma/EVW. Mean 0.4 mg QID (high) 0.38), P = .028

age 26 mo, 69% × 3 d, then 0.4 mg Proportion of children with exacerbations:

male, 35% with BID (high) × 7 d intermittent ICS (35%), placebo (38%)

eczema, 24% with via mask/spacer

positive skin-prick (started at first sign

test of a URTI)

Downloaded from by guest on March 7, 2017

6 KAISER et al

TABLE 1 Continued

Study Population Intervention (Dose Comparisons (Dose Study Outcomes

Category) Category) Duration

Szefler et al 2013 Children ages 24–48 Daily ICS: budesonide Montelukast: 4 mg 52 wk Primary outcome: median time to first asthma

(parallel RCT) mo with persistent 0.5 mg QHS via or 5 mg daily exacerbation: daily ICS (183 d), montelukast (86

asthma; mean age nebulizer (high), for based on age d), P = .128

56 mo, 61% male mild exacerbations Proportion of children with exacerbations: daily ICS

escalation to (21.9%), montelukast (37.1%)

budesonide 0.5 mg

BID via nebulizer

Wasserman et al Children 24–47 mo Daily ICS: 2 doses Placebo 12 wk Primary outcome: mean change in asthma symptom

2006 (parallel with persistent fluticasone score: daily ICS 44 μg (−0.5), daily ICS 88 μg

RCT) asthma; mean age suspension via (−0.7), placebo (−0.5), P < .05 comparing 88 μg

36 mo, 61% male mask/spacer used: to placebo

1) 44 μg BID (low), 2) Proportion of children with exacerbations: daily ICS

88 μg BID (medium) 44 μg (14%), daily ICS 88 μg (13%), placebo (24%)

Change in height from baseline (cm): daily ICS 44 μg

(1.8), daily ICS 88 μg (1.8), placebo (1.8)

Webb et al 1986 Children 18–72 mo; Daily ICS: Placebo 8 wk Primary outcome: total symptom score (median):

(crossover mean age 41 mo, beclomethasone daily (182), placebo (182), NS

RCT) 88% male, 44% 0.15 mg daily via Proportion of children with exacerbations: daily

with eczema nebulizer (medium) (23%), placebo (23%)

Wilson and Children 12–60 mo Intermittent ICS: Placebo plus Proportion of children with exacerbations:

Silverman with intermittent beclomethasone bronchodilator intermittent ICS (29%), placebo (42%)

1990 asthma/EVW; mean solution 0.75 mg plus TID × 5 d started

(crossover age 42 mo, 71% bronchodilator TID at the first sign

RCT) male (high) via MDI and of asthma attack

spacer × 5 d started

at the first sign of

asthma attack

Wilson et al 1995 Children 8–72 mo Daily ICS: budesonide Placebo 16 wk Primary outcome: daily symptom score (median):

(parallel RCT) with intermittent solution 0.2 mg BID daily (0.6), placebo (0.63), NS

asthma/EVW; mean via MDI with mask/ Proportion of children with exacerbations: daily

age 1.9 y, 59% spacer (medium) (10%), placebo (10%)

male, 82% with SFDs (median): daily (73%), placebo (78%)

family history of

asthma

Zeiger et al 2011 Children 12–53 mo Daily ICS: budesonide Intermittent ICS: 52 wk Primary outcome: rate of exacerbations per patient-

(parallel RCT) with intermittent 0.5 mg daily via budesonide year: daily (0.97), intermittent (0.95), NS

asthma/EVW and nebulizer (high) 1 mg BID via Proportion of children with exacerbations: daily

positive API; 46% nebulizer (44.6%), intermittent (46.0%)

between 12–23 started at the SFDs (mean percentage): daily (78%), intermittent

mo, 69% male, onset of URTI × 7 (78%)

53% with eczema, d (high) Change in height: daily (7.8 cm), intermittent (8.0

64% with parental cm)

asthma

API, asthma predictive index; BID, 2 times daily; MDI, metered dose inhaler; NS, not significant; PRN, as needed; QHS, at bedtime; QID, 4 times daily; TID, 3 times daily.

Data from 2 studies (N = 498) directly (n = 202) showed a significant no differences comparing daily ICS

comparing daily with intermittent reduction in rates of severe versus intermittent ICS (1/2 studies

ICS showed no differences in rates exacerbations with daily ICS versus excluded, RR 0.33; 95% CI, 0.07–

of severe exacerbations (25.7% and daily montelukast (21.9% and 37.1%, 1.62). With the exclusion of 3 out of

28.1%, respectively; RR 0.91; 95% CI, respectively; RR 0.59; 95% CI, 6 studies comparing intermittent

0.71–1.18; P = .49, I2 = 43%). 0.38–0.92; P = .02). ICS with placebo, the benefit of

Bacharier et al19 (n = 190) showed We performed sensitivity analyses intermittent ICS was no longer

no significant differences in rates excluding studies with high risk of statistically significant (RR 0.61;

of severe exacerbations comparing bias in ≥1 domain. Findings were 95% CI, 0.35–1.07). Both studies

intermittent ICS to intermittent similar to our primary analysis for comparing ICS with montelukast

montelukast (38.5% and 46.8%, 2 comparisons, with daily ICS better had high risk of bias in ≥1 domains.

respectively; RR 0.82; 95% CI, 0.59– than placebo (5/15 studies excluded, We also performed a sensitivity

1.15; P = .25). Szefler et al34 RR 0.67; 95% CI, 0.58–0.77) and analysis excluding only the 4 studies

Downloaded from by guest on March 7, 2017

PEDIATRICS Volume 137, number 6, June 2016 7

with intermittent ICS (1 study, n =

278; RR 0.97; 95% CI, 0.75–1.25)

or intermittent ICS compared with

intermittent montelukast (1 study,

n = 190; RR 0.82; 95% CI, 0.59–1.15).

Subgroup Analyses: Persistent Asthma

Our subgroup analyses of preschool

children with persistent asthma

are described in Fig 5. Eight studies

comparing daily ICS with placebo

were focused on children with

persistent asthma (N = 2505), and

showed a reduction in rates of

severe exacerbations with daily

ICS (8.7% vs 18%, respectively; RR

0.56; 95% CI, 0.46–0.70; P < .001;

I2 = 0%). Treatment of 11 children

prevented 1 child from experiencing

an exacerbation (NNT = 11; 95% CI,

8–15). Data from Szefler et al34 (n =

202) showed that daily ICS reduced

rates of severe exacerbations

compared with daily montelukast

(RR 0.59; 95% CI, 0.38–0.92; P = .02).

There were no studies of intermittent

ICS for children with persistent

asthma.

Subgroup Analyses: Unclear or Mixed

Wheezing Phenotypes

Our subgroup analyses of preschool

children with unclear or mixed

phenotypes are described in Fig

6. Six studies compared daily ICS

with placebo (N = 732) and showed

no significant difference in rates

FIGURE 2 of severe exacerbations (30.8% vs

Risk of Bias Diagram. 40.1%, respectively; RR 0.86; 95%

CI, 0.73–1.02; P = .08; I2 = 42%).

with crossover design and found ICS with placebo were focused on Data from Papi et al30 showed no

very similar results to our primary children with intermittent asthma significant difference comparing

analysis. or viral-triggered wheeze (5/6). intermittent ICS with placebo

(RR 0.61; 95% CI, 0.19–1.91; P = .40)

Data from these 5 studies (N = 422)

or daily ICS with intermittent ICS

Subgroup Analyses: Intermittent showed significant reduction in

(RR 0.33; 95% CI, 0.07–1.62; P = .17).

Asthma or Viral-Triggered Wheeze rates of severe exacerbations with

Our subgroup analyses of preschool intermittent ICS (33.9% vs 51.3%, Other Outcomes: Symptom-Free Days

children with intermittent asthma or respectively; RR 0.65; 95% CI, 0.51– and Linear Growth

viral-triggered wheeze are described 0.81; P = .0002; I2 = 0%). Treatment Seven studies comparing daily

in Fig 4. There was only 1 study of 6 children prevented 1 child ICS with placebo (N = 1336)

(n = 41) examining daily ICS versus from experiencing an exacerbation reported on symptom-free days

placebo, which found no significant (NNT = 6; 95% CI, 4–12). There (SFDs);7,22,24,30–32,37 however, few

benefit (RR 1.05; 95% CI, 0.16–6.76). was no difference in rates of severe provided adequate data for meta-

Most studies comparing intermittent exacerbations with daily compared analysis. Six of these studies31

Downloaded from by guest on March 7, 2017

8 KAISER et al

FIGURE 3

Meta-analyses of strategies for preventing severe exacerbations in preschoolers with recurrent wheeze. M-H, Mantel–Haenszel.

Downloaded from by guest on March 7, 2017

PEDIATRICS Volume 137, number 6, June 2016 9

FIGURE 4

Meta-analyses of strategies for preventing severe exacerbations in preschoolers with intermittent asthma or viral-triggered wheeze (subgroup analysis).

M-H, Mantel–Haenszel.

found a benefit with daily ICS, with Three studies compared daily ICS found no significant differences in

mean differences in percentage of with placebo.7,29,35 Wasserman mean change in height comparing

SFDs ranging from 5% to 23%. Two et al35 found no differences in growth intermittent ICS with montelukast

studies that compared daily and velocity during their 12-week study. or placebo over 1 year. Ducharme

intermittent ICS30,39 (N = 498) found Guilbert et al7 found that children et al27 found that intermittent ICS

no difference in SFDs. Bacharier treated with daily ICS had a 1.1 compared with placebo led to smaller

et al19 found no differences in SFDs cm lower mean increase in height mean change in height (6.23 ± 2.62

comparing intermittent ICS with at 2 years (12.6 ± 1.9 cm vs 13.7 ± cm vs 6.56 ± 2.90 cm) and height z

intermittent montelukast or placebo. 1.9 cm, P < .001), but 1 year after score (−0.19 ± 0.42 vs 0.00 ± 0.48)

discontinuation of ICS, the difference over 1 year. Zeiger et al39 found

We also reviewed linear growth in height increase was reduced to no significant differences in mean

effects, because this is the major 0.7 cm (19.2 ± 2.2 cm vs 19.9 ± 2.2 change in height, height percentile,

concerning side effect with ICS.5 cm, P = .008). Murray et al29 found or z score comparing daily with

We were unable to meta-analyze a significantly smaller change in intermittent ICS over 1 year.

these data given the small number mean height z score after 6 months

of studies reporting growth data and of daily ICS but no differences at 1, DISCUSSION

the varied growth metrics reported. 2, or 5 years of follow-up. In studies

Six studies reported on linear growth comparing intermittent ICS with With this analysis, we aimed to

outcomes7,19,27, 29,35,39 (N = 1461). placebo,19,27,39 Bacharier et al19 synthesize the evidence of the effects

Downloaded from by guest on March 7, 2017

10 KAISER et al

FIGURE 5

Meta-analyses of strategies for preventing severe exacerbations in preschoolers with persistent asthma (subgroup analysis). M-H, Mantel–Haenszel.

of daily ICS, intermittent ICS, and found that daily ICS was effective in dosing to the lowest dose that is

montelukast in preventing severe reducing the risk of severe wheezing effective.

exacerbations among preschool exacerbations (NNT = 9), in line

children with recurrent wheeze. with a meta-analysis done in 2009.6 Our subgroup analyses by wheezing

In our primary analysis, we found Daily ICS also led to an increase in phenotype showed that most

that both daily and intermittent ICS SFDs. These findings are in line with studies of daily ICS in preschool

were effective in preventing severe studies in older children and adults children have focused on children

exacerbations. Daily ICS reduced that have established ICS as the most with persistent asthma. For these

the risk of exacerbations by 30%, potent and consistently effective children, we found strong evidence

intermittent ICS reduced risk by long-term control medication to support daily ICS, with data from

36%, and there were no significant for asthma.5 The broad action of >1600 children demonstrating 44%

differences when these strategies ICS on the inflammatory process reduced risk of severe exacerbations

were compared directly. Given probably accounts for their efficacy (NNT = 11). In addition, most studies

the varying patterns of recurrent as preventive therapy.5 Overall, the that reported on symptom-free days

wheezing in preschool children, we growth-suppressive effects of ICS found significant improvements

performed subgroup analyses by in preschool children improved with daily ICS compared with

wheezing phenotype. In line with over time in most children.7,29, placebo.22,24,32 We also found that daily

the 2007 National Asthma Education 35 A follow-up study by Guilbert

ICS reduced risk of exacerbations more

and Prevention Program guideline, et al41 found that children started than montelukast, but these data

we found strong evidence to support on daily ICS at a younger age (<2 were limited to a single study. These

daily ICS for preschool children with years) or lower weight (<15 kg) may findings support current national and

persistent asthma. For preschool experience greater effects on linear international guidelines,5,8,11 which

children with intermittent asthma or growth. A Cochrane meta-analysis recommend daily ICS as first-line

viral-triggered wheeze, we found strong found dose–response effects of ICS therapy for preschool children with

evidence to support intermittent ICS. on growth.42 Consequently, persistent asthma.

children on ICS should have regular

In our primary analysis of preschool monitoring of growth, and health We also performed a subgroup

children with recurrent wheeze, we care providers should titrate ICS analysis of preschool children

Downloaded from by guest on March 7, 2017

PEDIATRICS Volume 137, number 6, June 2016 11

FIGURE 6

Meta-analyses of strategies for preventing severe exacerbations in preschoolers with unclear or mixed wheezing phenotypes (subgroup analysis). M-H,

Mantel–Haenszel.

with intermittent asthma or viral- found no differences; they also compare the efficacy of intermittent

triggered wheeze, because this is found that intermittent ICS led to a ICS, daily ICS, and montelukast for

the most common wheezing pattern lower cumulative dose than daily this population.

in this age group.1 Most studies ICS. Ducharme et al27 found slower

evaluated intermittent ICS. We linear growth in children treated Previous systematic reviews of these

found strong evidence to support with intermittent ICS compared with therapies have either not focused on

intermittent ICS, with a 35% risk placebo. However, Bacharier et al19 preschool children or not compiled

reduction in severe exacerbations (intermittent ICS versus placebo) and data on multiple therapeutic

(NNT = 6). In these studies, children Zeiger et al39 (intermittent versus strategies (daily ICS, intermittent

generally received high-dose ICS daily ICS) found no differences ICS, and montelukast). Our findings

started at the first sign of a URTI in linear growth. Overall, there is are in line with previous studies

for 7 to 10 days. The children strong evidence to support the safety that combined pediatric and adult

studied had minimal wheezing and efficacy of intermittent ICS for data or examined a single therapy.

between URTIs, but the majority preschool children with intermittent A 2009 meta-analysis compared

had a history of moderate to severe asthma or viral-triggered wheeze, daily ICS with placebo in preschool

wheezing exacerbations with URTI including those with severe children with recurrent wheeze

necessitating systemic steroids, intermittent wheezing, in line with and found a similar reduction in

emergency department visits, and the 2015 Global Initiative for Asthma wheezing exacerbations (RR 0.59;

hospitalizations (severe intermittent guideline.11 We found limited data 95% CI, 0.52–0.67; P = .0001;

wheezing).19,27,33,38 There were directly comparing montelukast with I2 = 10%).6 A 2015 Cochrane meta-

limited data for daily ICS in this ICS, and a recent Cochrane meta- analysis comparing intermittent

population, with only 1 small study analysis comparing montelukast ICS with placebo found a reduction

comparing daily ICS with placebo with placebo for preschool children in wheezing exacerbations with

(N = 41) that found no difference. with viral-triggered wheezing found intermittent ICS in a subgroup

Zeiger et al39 directly compared no benefit with montelukast.43 More analysis of preschool children

daily ICS with intermittent ICS and studies are needed that directly (odds ratio 0.48; 95% CI, 0.31–0.73;

Downloaded from by guest on March 7, 2017

12 KAISER et al

P < .001).44 In addition, a 2013 on children with persistent asthma, This is the first study to our

Cochrane meta-analysis comparing and most studies of intermittent ICS knowledge to systematically review

intermittent and daily ICS found no focused on children with intermittent and meta-analyze the effects of

significant differences in a subgroup asthma or viral-triggered wheezing. daily ICS, intermittent ICS, and

analysis of preschool children (RR Studies of intermittent ICS may montelukast in preventing severe

1.09; 95% CI, 0.85–1.41; P = .49).45 have also preferentially recruited exacerbations among preschool

In 2015, Ducharme et al13 published children with higher baseline risk, children with recurrent wheeze.

a nonsystematic review of preschool because rates of exacerbations We performed a thorough and

wheeze with meta-analyses of in placebo groups were higher in extensive search of the literature.

newer studies; they reported similar studies comparing intermittent Our overall study population was

results comparing daily ICS with ICS with placebo (41.6%) than in large, including 4756 children from

placebo (relative risk 0.57; 95% CI, studies comparing daily ICS with centers across the world. We found

0.40–0.80) and daily and intermittent placebo (24.0%). The differences in strong evidence to support daily ICS

ICS (relative risk 0.91; 95% CI, study groups recruited for testing for preventing severe exacerbations

0.71–1.18). The conclusions of a 2016 these strategies may correlate with in preschool children with recurrent

nonsystematic review by Castro- treatment response, given that wheeze, specifically in children with

Rodriguez et al46 were also in line we found treatment benefits in persistent asthma. For preschool

with our findings. phenotypically homogenous groups children with intermittent asthma

and did not find benefits in a group or viral-triggered wheeze, we

with mixed or unclear phenotypes. found strong evidence to support

One limitation to our study is

However, phenotypic classification intermittent ICS for preventing

heterogeneity among the included

of recurrent wheezing in preschool exacerbations. With either

studies. We found moderate

children has limitations. Although the treatment strategy, we recommend

heterogeneity in our primary analyses

pattern of episodic viral wheeze has frequent reassessment of wheezing

of daily ICS versus placebo and daily

been well described in the literature symptoms and pattern, close

versus intermittent ICS. Sources of

and advocated as a management tool monitoring of growth, and active

heterogeneity likely include variations

by a European Respiratory Society titration to the lowest ICS dose

in clinical factors (population, study

Task Force,8 recent studies have that is effective. More studies are

duration, cointerventions) and study demonstrated that most preschool needed that directly compare these

design (parallel vs crossover). As children quickly change from 1 therapies.

expected, when we narrowed to more phenotype to another.47 Given these

homogenous studies in our subgroup limitations, therapeutic decisions

analyses, heterogeneity improved. remain challenging until more ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Another limitation was the inclusion studies are conducted that clearly We thank Elizabeth M. Uleryk for

of studies that had a high risk of bias describe the disease pattern and helping develop our search strategy

in ≥1 domain, usually because of baseline risk of enrolled children and Dr Prakesh S. Shah for technical

incomplete outcome data. To address and directly compare daily ICS, guidance with the design and analysis

the influence of this potential bias, we intermittent ICS, and montelukast. of this study.

ran sensitivity analyses that excluded Our findings show significant

these studies, which were in line with reductions in risk of moderate to

our primary findings. Additionally, severe exacerbations with ICS, and

the majority of studies included they support initiation of ICS therapy

children <2 years, so they may in preschool children with symptoms ABBREVIATIONS

include some children with of persistent asthma or those with

BID: twice daily

bronchiolitis. However, all studies high risk of severe exacerbations

CI: confidence interval

required children to have recurrent (>1 course of systemic steroids

EVW: episodic viral wheeze

wheezing, and many additionally per year).5 Reasonable therapeutic

ICS: inhaled corticosteroids

required other criteria that should strategies include initiation of daily

NNT: number needed to treat

have minimized recruitment ICS5 or intermittent ICS11 and should

RR: risk ratio

of children with bronchiolitis be based on symptom pattern, risk

RCT: randomized controlled

(bronchodilator response, risk factors of severe exacerbations,5 and risk

trial

for asthma). of developing chronic asthma.40

SFDs: symptom-free days

Therapy should be reevaluated

URTI: upper respiratory tract

Our subgroup analyses highlighted frequently and adjusted based on

infection

that most studies of daily ICS focused symptom pattern.

Downloaded from by guest on March 7, 2017

PEDIATRICS Volume 137, number 6, June 2016 13

DOI: 10.1542/peds.2015-4496

Accepted for publication Mar 16, 2016

Address correspondence to Sunitha V. Kaiser, MD, MSc, 550 16th St, Box 3214, San Francisco, CA 94158. E-mail: sunitha.kaiser@ucsf.edu

PEDIATRICS (ISSN Numbers: Print, 0031-4005; Online, 1098-4275).

Copyright © 2016 by the American Academy of Pediatrics

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

FUNDING: No external funding.

POTENTIAL CONFLICT OF INTEREST: Dr Bacharier has received consulting fees from Merck and Teva and payment for lectures from Astra Zeneca and Teva; Dr

Cabana has served as a consultant for Genentech (Data Registry Safety Board) and Merck (Speaker’s Bureau); and the other authors have indicated they have no

potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

1. Martinez FD, Wright AL, Taussig LM, corticosteroids in preschool children 2000–2009. J Pediatr. 2013;163:1127–

Holberg CJ, Halonen M, Morgan at high risk for asthma. N Engl J Med. 1133 e3

WJ; The Group Health Medical 2006;354(19):1985–1997 16. Davies BR, Carroll WD. The use of

Associates. Asthma and wheezing in inhaled corticosteroids in the wheezy

the first six years of life. N Engl J Med. 8. Brand PL, Baraldi E, Bisgaard H, et al.

Definition, assessment and treatment under 5-year-old child. Arch Dis Child

1995;332(3):133–138 Educ Pract Ed. 2011;96(2):61–66

of wheezing disorders in preschool

2. Laforest L, Yin D, Kocevar VS, et al. children: an evidence-based approach. 17. Gionfriddo MR, Hagan JB, Hagan CR,

Association between asthma control Eur Respir J. 2008;32(4):1096–1110 Volcheck GW, Castaneda-Guarderas

in children and loss of workdays

A, Rank MA. Stepping down inhaled

by caregivers. Ann Allergy Asthma 9. Bacharier LB, Phillips BR, Bloomberg

corticosteroids from scheduled to as

Immunol. 2004;93(3):265–271 GR, et al; Childhood Asthma Research

needed in stable asthma: Systematic

and Education Network, National Heart,

3. American Lung Association. Asthma review and meta-analysis. Allergy

Lung, and Blood Institute. Severe

& children fact sheet. 2014. Available Asthma Proc. 2015;36(4):262–267

intermittent wheezing in preschool

at: www.lung.org/lung-health-and-

children: a distinct phenotype. J Allergy 18. Higgins JPAD, Gøtzsche PC, Jüni P, et

diseases/lung-disease-lookup/asthma/

Clin Immunol. 2007;119(3):604–610 al; Cochrane Bias Methods Group.

learn-about-asthma/asthma-children-

Cochrane Statistical Methods Group.

facts-sheet.html?referrer=https:// 10. Chipps BE, Bacharier LB, Harder JM.

The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for

www.google.com/ Phenotypic expressions of childhood

assessing risk of bias in randomised

wheezing and asthma: implications for

4. Centers for Disease Control and trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d5928

therapy. J Pediatr. 2011;158:878–84 e1

Prevention. National surveillance

19. Bacharier LB, Phillips BR, Zeiger RS, et

of asthma. Atlanta, GA: Centers for 11. Global Initiative for Asthma. Global

al; CARE Network. Episodic use of an

Disease Control and Prevention; Strategy for Asthma Management

inhaled corticosteroid or leukotriene

2012:2001–2010 and Prevention. Available at: www.

receptor antagonist in preschool

ginasthma.org

5. National Asthma Education and children with moderate-to-severe

Prevention Program. Expert panel 12. Sawicki GS, Smith L, Bokhour B, et intermittent wheezing. J Allergy Clin

report 3 (EPR-3): guidelines for al. Periodic use of inhaled steroids Immunol. 2008;122(6):1127–1135.e8

the diagnosis and management of in children with mild persistent

20. Bisgaard H, Gillies J, Groenewald

asthma—summary report 2007. asthma: what are pediatricians

M, Maden C. The effect of inhaled

[Erratum appears in J Allergy recommending? Clin Pediatr (Phila).

fluticasone propionate in the

Clin Immunol. 2008;121(6):1330] J 2008;47(5):446–451

treatment of young asthmatic children:

Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;120(5

13. Ducharme FM, Tse SM, Chauhan a dose comparison study. Am J Respir

suppl):S94–S138

B. Diagnosis, management, and Crit Care Med. 1999;160(1):126–131

6. Castro-Rodriguez JA, Rodrigo GJ. prognosis of preschool wheeze. Lancet.

21. Brand PLP, Luz García-García M,

Efficacy of inhaled corticosteroids 2014;383(9928):1593–1604

Morison A, Vermeulen JH, Weber

in infants and preschoolers with 14. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman HC. Ciclesonide in wheezy preschool

recurrent wheezing and asthma: a DG, Group P; PRISMA Group. Preferred children with a positive asthma

systematic review with meta-analysis. reporting items for systematic reviews predictive index or atopy. Respir Med.

Pediatrics. 2009;123(3). Available at: and meta-analyses: the PRISMA 2011;105(11):1588–1595

www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/ statement. BMJ. 2009;339:b2535

123/3/e519 22. Carlsen KCL, Stick S, Kamin W, Cirule

15. Hasegawa K, Tsugawa Y, Brown DF, I, Hughes S, Wixon C. The efficacy and

7. Guilbert TW, Morgan WJ, Zeiger Camargo CA, Jr. Childhood asthma safety of fluticasone propionate in

RS, et al. Long-term inhaled hospitalizations in the United States, very young children with persistent

Downloaded from by guest on March 7, 2017

14 KAISER et al

asthma symptoms. Respir Med. inhalation aerosol in pre-school-age children with recurrent wheezing. N

2005;99(11):1393–1402 children with asthma: a randomized, Engl J Med. 2011;365(21):1990–2001

23. Connett G, Lenney W. Prevention of double-blind, placebo-controlled study.

40. Castro-Rodríguez JA, Holberg CJ,

viral induced asthma attacks using J Pediatr. 2006;149(5):663–670

Wright AL, Martinez FD. A clinical index

inhaled budesonide. Arch Dis Child. 32. Roorda RJ, Mezei G, Bisgaard H, Maden to define risk of asthma in young

1993;68(1):85–87 C. Response of preschool children children with recurrent wheezing. Am

24. Connett GJ, Warde C, Wooler E, Lenney with asthma symptoms to fluticasone J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;162(4 pt

W. Use of budesonide in severe propionate. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1):1403–1406

asthmatics aged 1-3 years. Arch Dis 2001;108(4):540–546 41. Guilbert TW, Mauger DT, Allen DB,

Child. 1993;69(3):351–355 33. Svedmyr J, Nyberg E, Thunqvist Zeiger RS, Lemanske RF, Jr., Szefler

25. de Benedictis FM, Martinati LC, P, Asbrink-Nilsson E, Hedlin G. SJ, et al Growth of preschool children

Solinas LF, Tuteri G, Boner AL. Prophylactic intermittent treatment at high risk for asthma 2 years after

Nebulized flunisolide in infants with inhaled corticosteroids of discontinuation of fluticasone. J Allergy

and young children with asthma: asthma exacerbations due to airway Clin Immunol. 2011;128:956–63 e1–7

a pilot study. Pediatr Pulmonol. infections in toddlers. Acta Paediatr. 42. Pruteanu AI, Chauhan BF, Zhang L,

1996;21(5):310–315 1999;88(1):42–47 Prietsch SO, Ducharme FM. Inhaled

34. Szefler SJ, Carlsson LG, Uryniak T, corticosteroids in children with

26. de Blic J, Delacourt C, Le Bourgeois M,

Baker JW. Budesonide inhalation persistent asthma: dose–response

et al. Efficacy of nebulized budesonide

suspension versus montelukast in effects on growth. Cochrane Database

in treatment of severe infantile

children aged 2 to 4 years with mild Syst Rev. 2014;7:CD009878

asthma: a double-blind study. J Allergy

Clin Immunol. 1996;98(1):14–20 persistent asthma. J Allergy Clin 43. Brodlie M, Gupta A, Rodriguez-Martinez

Immunol Pract. 2013;1(1):58–64 CE, Castro-Rodriguez JA, Ducharme

27. Ducharme FM, Lemire C, Noya FJD,

35. Wasserman RL, Baker JW, Kim FM, McKean MC. Leukotriene receptor

et al. Preemptive use of high-dose

KT, et al. Efficacy and safety of antagonists as maintenance and

fluticasone for virus-induced wheezing

inhaled fluticasone propionate intermittent therapy for episodic

in young children. N Engl J Med.

chlorofluorocarbon in 2- to 4-year- viral wheeze in children. Cochrane

2009;360(4):339–353

old patients with asthma: results of Database Syst Rev. 2015;10:CD008202

28. Gleeson JG, Price JF. Controlled trial of a double-blind, placebo-controlled 44. Chong J, Haran C, Chauhan BF, Asher

budesonide given by the nebuhaler in study. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. I. Intermittent inhaled corticosteroid

preschool children with asthma. BMJ. 2006;96(6):808–818 therapy versus placebo for persistent

1988;297(6642):163–166 asthma in children and adults.

36. Webb MS, Milner AD, Hiller EJ, Henry

29. Murray CS, Woodcock A, Langley SJ, RL. Nebulised beclomethasone Cochrane Database Syst Rev.

Morris J, Custovic A; IFWIN Study Team. dipropionate suspension. Arch Dis 2015;7:CD011032

Secondary prevention of asthma by the Child. 1986;61(11):1108–1110 45. Chauhan BF, Chartrand C, Ducharme

use of Inhaled Fluticasone Propionate 37. Wilson N, Sloper K, Silverman M. Effect FM. Intermittent versus daily inhaled

in Wheezy Infants (IFWIN): double-blind, of continuous treatment with topical corticosteroids for persistent asthma

randomised, controlled study. Lancet. corticosteroid on episodic viral wheeze in children and adults. Cochrane

2006;368(9537):754–762 in preschool children. Arch Dis Child. Database Syst Rev. 2013;2:CD009611

30. Papi A, Nicolini G, Baraldi E, et al; 1995;72(4):317–320 46. Castro-Rodriguez JA, Custovic A,

Beclomethasone and Salbutamol 38. Wilson NM, Silverman M. Treatment of Ducharme FM. Treatment of asthma

Treatment (BEST) for Children acute, episodic asthma in preschool in young children: evidence-based

Study Group. Regular vs prn children using intermittent high dose recommendations. Asthma Res Pract.

nebulized treatment in wheeze inhaled steroids at home. Arch Dis 2016;2:5

preschool children. Allergy. Child. 1990;65(4):407–410 47. van Wonderen KEGR, Geskus RB, van

2009;64(10):1463–1471

39. Zeiger RS, Mauger D, Bacharier LB, et Aalderen WM, et al. Stability and

31. Qaqundah PY, Sugerman RW, Ceruti E, al; CARE Network of the National Heart, predictiveness of multiple trigger and

et al. Efficacy and safety of fluticasone Lung, and Blood Institute. Daily or episodic viral wheeze in preschoolers.

propionate hydrofluoroalkane intermittent budesonide in preschool Clin Exp Allergy. 2015. 10.1111/cea.12660

Downloaded from by guest on March 7, 2017

PEDIATRICS Volume 137, number 6, June 2016 15

Preventing Exacerbations in Preschoolers With Recurrent Wheeze: A

Meta-analysis

Sunitha V. Kaiser, Tram Huynh, Leonard B. Bacharier, Jennifer L. Rosenthal, Leigh

Anne Bakel, Patricia C. Parkin and Michael D. Cabana

Pediatrics 2016;137;; originally published online May 26, 2016;

DOI: 10.1542/peds.2015-4496

Updated Information & including high resolution figures, can be found at:

Services /content/137/6/e20154496.full.html

Supplementary Material Supplementary material can be found at:

/content/suppl/2016/05/18/peds.2015-4496.DCSupplemental.

html

References This article cites 44 articles, 12 of which can be accessed free

at:

/content/137/6/e20154496.full.html#ref-list-1

Citations This article has been cited by 1 HighWire-hosted articles:

/content/137/6/e20154496.full.html#related-urls

Subspecialty Collections This article, along with others on similar topics, appears in

the following collection(s):

Pulmonology

/cgi/collection/pulmonology_sub

Asthma

/cgi/collection/asthma_subtopic

Permissions & Licensing Information about reproducing this article in parts (figures,

tables) or in its entirety can be found online at:

/site/misc/Permissions.xhtml

Reprints Information about ordering reprints can be found online:

/site/misc/reprints.xhtml

PEDIATRICS is the official journal of the American Academy of Pediatrics. A monthly

publication, it has been published continuously since 1948. PEDIATRICS is owned, published,

and trademarked by the American Academy of Pediatrics, 141 Northwest Point Boulevard, Elk

Grove Village, Illinois, 60007. Copyright © 2016 by the American Academy of Pediatrics. All

rights reserved. Print ISSN: 0031-4005. Online ISSN: 1098-4275.

Downloaded from by guest on March 7, 2017

Preventing Exacerbations in Preschoolers With Recurrent Wheeze: A

Meta-analysis

Sunitha V. Kaiser, Tram Huynh, Leonard B. Bacharier, Jennifer L. Rosenthal, Leigh

Anne Bakel, Patricia C. Parkin and Michael D. Cabana

Pediatrics 2016;137;; originally published online May 26, 2016;

DOI: 10.1542/peds.2015-4496

The online version of this article, along with updated information and services, is

located on the World Wide Web at:

/content/137/6/e20154496.full.html

PEDIATRICS is the official journal of the American Academy of Pediatrics. A monthly

publication, it has been published continuously since 1948. PEDIATRICS is owned,

published, and trademarked by the American Academy of Pediatrics, 141 Northwest Point

Boulevard, Elk Grove Village, Illinois, 60007. Copyright © 2016 by the American Academy

of Pediatrics. All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 0031-4005. Online ISSN: 1098-4275.

Downloaded from by guest on March 7, 2017

You might also like

- 2022 - Invasive Brain Tissue Oxygen and Intracranial Pressure (ICP) Monitoring Versus ICP-only Monitoring in Pediatric Severe Traumatic Brain InjurDocument11 pages2022 - Invasive Brain Tissue Oxygen and Intracranial Pressure (ICP) Monitoring Versus ICP-only Monitoring in Pediatric Severe Traumatic Brain InjurnadiaNo ratings yet

- Nihms 1560715Document24 pagesNihms 1560715nadiaNo ratings yet

- Sem6 - Status EpilepticusDocument9 pagesSem6 - Status EpilepticusnadiaNo ratings yet

- Epilepsi Mexico Diagnostico 2020Document6 pagesEpilepsi Mexico Diagnostico 2020nadiaNo ratings yet

- Epilepsi Mexico Diagnostico 2020Document6 pagesEpilepsi Mexico Diagnostico 2020nadiaNo ratings yet

- Plantilla CelesteDocument55 pagesPlantilla CelestenadiaNo ratings yet

- Sedacion en Pacientes Pédiatricos 2021Document26 pagesSedacion en Pacientes Pédiatricos 2021nadiaNo ratings yet

- Critical Update 3r Edicion 2020Document6 pagesCritical Update 3r Edicion 2020nadiaNo ratings yet

- Quality Improvement Studies in Pediatric Critical Care MedicineDocument7 pagesQuality Improvement Studies in Pediatric Critical Care MedicinenadiaNo ratings yet

- Critical Update 3r Edicion 2020Document6 pagesCritical Update 3r Edicion 2020nadiaNo ratings yet

- ESTADO EPILEPTICO Singh2020 - Article - PharmacotherapyForPediatricConDocument17 pagesESTADO EPILEPTICO Singh2020 - Article - PharmacotherapyForPediatricConnadiaNo ratings yet

- Hipotermia 2020Document8 pagesHipotermia 2020nadiaNo ratings yet

- Reversible Airway Obstruction in Cystic Fibrosis: Common, But Not Associated With Characteristics of AsthmaDocument8 pagesReversible Airway Obstruction in Cystic Fibrosis: Common, But Not Associated With Characteristics of AsthmanadiaNo ratings yet

- Advances in Pediatric Sepsis and Shock: E. Scott HalsteadDocument2 pagesAdvances in Pediatric Sepsis and Shock: E. Scott HalsteadnadiaNo ratings yet

- Pediatric Head Trauma: A Review and Update: Practice GapsDocument16 pagesPediatric Head Trauma: A Review and Update: Practice GapsnadiaNo ratings yet

- Cetoacidosis Diabetica Pediattrica InglessDocument17 pagesCetoacidosis Diabetica Pediattrica InglessnadiaNo ratings yet

- Thoracicneoplasms Inchildren: Beverley NewmanDocument32 pagesThoracicneoplasms Inchildren: Beverley NewmannadiaNo ratings yet

- Review Differentiates Between Adult and Child Asthma TreatmentsDocument10 pagesReview Differentiates Between Adult and Child Asthma TreatmentsnadiaNo ratings yet

- Hiperplasis Congenita AFRICADocument6 pagesHiperplasis Congenita AFRICAnadiaNo ratings yet

- Inborn Errors of Metabolism (Metabolic Disorders) : Educational GapsDocument17 pagesInborn Errors of Metabolism (Metabolic Disorders) : Educational Gapsusmani_nida1No ratings yet

- Mutsaers2009 Churg StraussDocument3 pagesMutsaers2009 Churg StraussnadiaNo ratings yet

- High-Flow Oxygen Therapy in Infants With Bronchiolitis: To The EditorDocument4 pagesHigh-Flow Oxygen Therapy in Infants With Bronchiolitis: To The EditornadiaNo ratings yet

- Mutsaers2009 Churg StraussDocument3 pagesMutsaers2009 Churg StraussnadiaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 5 Glucose HomeostasisDocument15 pagesChapter 5 Glucose Homeostasistliviu334066No ratings yet

- Rapid Diagnosis in Ophthalmology Series - Neuro-Ophthalmology-0323044565Document241 pagesRapid Diagnosis in Ophthalmology Series - Neuro-Ophthalmology-0323044565ahsananwer100% (6)

- Distres Consensus 1Document19 pagesDistres Consensus 1ДенисДемченкоNo ratings yet

- Gland Ula Supra R RenalDocument23 pagesGland Ula Supra R RenalnadiaNo ratings yet

- Art11 PDFDocument11 pagesArt11 PDFKarina Vanessa María Llanos YupanquiNo ratings yet

- Diagnóstico Molecular de Inmunodeficiencias PrimariasDocument7 pagesDiagnóstico Molecular de Inmunodeficiencias PrimariasnadiaNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5784)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Case Report: Communication Strategies For Empowering and Protecting ChildrenDocument9 pagesCase Report: Communication Strategies For Empowering and Protecting ChildrennabilahNo ratings yet

- Context & Interested Party AnalysisDocument6 pagesContext & Interested Party AnalysisPaula Angelica Tabia CruzNo ratings yet

- A Harmonious Smile: Biological CostsDocument12 pagesA Harmonious Smile: Biological Costsjsjs kaknsbsNo ratings yet

- 1 - DS SATK Form - Initial Application of LTO 1.2Document4 pages1 - DS SATK Form - Initial Application of LTO 1.2cheska yahniiNo ratings yet

- WORKPLACE TB POLICYDocument4 pagesWORKPLACE TB POLICYGigi CabanaNo ratings yet

- StramoniumDocument114 pagesStramoniumJoão FrancoNo ratings yet

- Tuition Appeal Guidelines ExplainedDocument2 pagesTuition Appeal Guidelines ExplainedEnock DadzieNo ratings yet

- 58-Article Text-228-1-10-20180325Document11 pages58-Article Text-228-1-10-20180325mutiara nancyNo ratings yet

- Case Control Study For MedicDocument41 pagesCase Control Study For Medicnunu ahmedNo ratings yet

- Heavy Water Board RecruitmentDocument7 pagesHeavy Water Board RecruitmentramavarshnyNo ratings yet

- Hazards of Dietary Supplement Use: Anthony E. Johnson, MD Chad A. Haley, MD John A. Ward, PHDDocument10 pagesHazards of Dietary Supplement Use: Anthony E. Johnson, MD Chad A. Haley, MD John A. Ward, PHDJean CotteNo ratings yet

- Environmental Hazards For The Nurse As A Worker - Nursing Health, & Environment - NCBI Bookshelf PDFDocument6 pagesEnvironmental Hazards For The Nurse As A Worker - Nursing Health, & Environment - NCBI Bookshelf PDFAgung Wicaksana100% (1)

- Influence of Social Capital On HealthDocument11 pagesInfluence of Social Capital On HealthHobi's Important BusinesseuNo ratings yet

- Management of Class I Type 3 Malocclusion Using Simple Removable AppliancesDocument5 pagesManagement of Class I Type 3 Malocclusion Using Simple Removable AppliancesMuthia DewiNo ratings yet

- Kaplan Grade OverviewDocument5 pagesKaplan Grade Overviewapi-310875630No ratings yet

- Surgery Final NotesDocument81 pagesSurgery Final NotesDETECTIVE CONANNo ratings yet

- Summer Internship Report on Chemist Behavior Towards Generic ProductsDocument30 pagesSummer Internship Report on Chemist Behavior Towards Generic ProductsBiswadeep PurkayasthaNo ratings yet

- MudreDocument10 pagesMudrejezebelvertNo ratings yet

- Facts of MaintenanceDocument9 pagesFacts of Maintenancegeorge youssefNo ratings yet

- PH 021 enDocument4 pagesPH 021 enjohnllenalcantaraNo ratings yet

- UK Requirements Checklist and Study MaterialsDocument2 pagesUK Requirements Checklist and Study MaterialsKrizle AdazaNo ratings yet

- ICU antibiotic susceptibilities guideDocument1 pageICU antibiotic susceptibilities guideFaisal Reza AdiebNo ratings yet

- 'No Evidence That CT Scans, X-Rays Cause Cancer' - Medical News TodayDocument3 pages'No Evidence That CT Scans, X-Rays Cause Cancer' - Medical News TodayDr-Aditya ChauhanNo ratings yet

- Sdera Demo Lesson DVD Worksheet 2021Document2 pagesSdera Demo Lesson DVD Worksheet 2021api-396577001No ratings yet

- JUSTINE Medical-for-Athletes-2-1Document2 pagesJUSTINE Medical-for-Athletes-2-1joselito papa100% (1)

- Gurr2011-Probleme Psihologice Dupa Atac CerebralDocument9 pagesGurr2011-Probleme Psihologice Dupa Atac CerebralPaulNo ratings yet

- Practitioner Review of Treatments for AutismDocument18 pagesPractitioner Review of Treatments for AutismAlexandra AddaNo ratings yet

- RPNDocument21 pagesRPNAruna Teja Chennareddy43% (7)

- Scoring BPSDDocument4 pagesScoring BPSDayu yuliantiNo ratings yet

- Report SampleDocument11 pagesReport SampleArvis ZohoorNo ratings yet