Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Canine Chronic Hepatitis: Diagnosis & Treatment

Uploaded by

Thamil ArasanOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Canine Chronic Hepatitis: Diagnosis & Treatment

Uploaded by

Thamil ArasanCopyright:

Available Formats

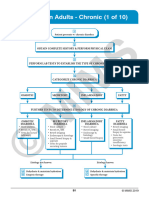

Peer Reviewed CANINE CHRONIC HEPATITIS: DIAGNOSIS & TREATMENT

DIAGNOSIS & TREATMENT

Canine Chronic Hepatitis

Yuri Lawrence, DVM, MA, MS, Diplomate ACVIM

Jörg Steiner, MedVet, DrMedVet, PhD, Diplomate ACVIM & ECVIM

Texas A&M University

Chronic hepatitis is the most common liver

Table 1.

disease in dogs. The World Small Animal Veterinary

Known Causes of Canine Chronic Hepatitis

Association Liver Standardization Group has

published standards for diagnosis of the various CAUsE sPECIFIC EXAMPLEs

forms of chronic hepatitis.1 This article reviews the Drug • Amiodarone

current literature on diagnosis and treatment of • Carprofen

canine chronic hepatitis. • Diethylcarbamazine–

oxibendazole

• Phenobarbital

PROFILE • Trimethoprim/sulfadiazine

Chronic hepatitis is characterized by hepatocellular Infectious Disease • Canine adenovirus type 1

apoptosis or necrosis, a variable mononuclear or • Helicobacter species

mixed inflammatory cell infiltrate, regeneration, and • Herpesvirus

fibrosis on histopathologic examination.1 • Leptospirosis

Clinicopathologic

examination is Genetic Disease/ • Alpha-1-proteinase inhibitor

an important Inherited Defecta deficiency

Predisposition

component of

The Doberman, West Highland white terrier, Other Disease/ • Autoimmune mechanismsb

screening for Condition

Labrador retriever, Skye terrier, American cocker • Copper hepatotoxicosis

evidence of chronic

spaniel, English cocker spaniel, standard poodle, and • Episode of acute hepatitis

hepatitis and

• Various toxicities

concurrent disease, Bedlington terrier breeds are predisposed to chronic

and evaluating the a. Associated with chronic hepatitis in cocker spaniels,

hepatitis.2 but causation—as described in humans—has not been

systemic status of

established in dogs8

the patient. b. Suggested to cause chronic hepatitis in dogs but have

Causes never been confirmed experimentally9

In most cases of canine chronic hepatitis, the cause

is unknown. Known causes are outlined in Table Table 2.

1.3-9 The cause, if known, should precede the term Chronic Hepatitis: Clinical signs & Physical

chronic hepatitis. Examination Findings

CLINICAL PHYsICAL

INITIAL FINDINGS sIGNs EXAMINATIoN

Clinical Signs FINDINGs

Patients with chronic hepatitis often present with

• Abdominal distensiona,b • Ascitesc

nonspecific clinical signs, although more specific • Emesis/diarrhea • Abnormal mucous

signs may occur in patients with advanced disease • Hepatoencephalopathya membrane color

(Table 2). Some affected dogs are asymptomatic at • Hyporexia (due to jaundice)

presentation, and clinical signs may be inapparent in • Jaundice • Abnormal capillary

• Lethargy refill time

patients with compensated advanced disease. • Polydipsia/polyuria (due to hypovolemia)

• Weight loss • Icterus

Physical Examination a. Accompanies advanced disease

Physical examination findings for chronic hepatitis b. Due to ascites from portal hypertension and/or

hypoproteinemia

are nonspecific, often normal and, in most cases, c. Identified as negative prognostic indicator in patients

with chronic hepatitis10,11

do not provide any information to identify the

26 TODAY’S VETERINARY PRACTICE | March/April 2015 | tvpjournal.com

CANINE CHRONIC HEPATITIS: DIAGNOSIS & TREATMENT Peer Reviewed

affected system unless the patient has jaundice (Table our opinion, the most useful test (in the absence of

2). Laboratory investigation is required to further hyperbilirubinemia), is the provocative serum total

evaluate patients for chronic hepatitis. bile acids test, which includes a fasted preprandial and

2-hour postprandial (provoked) serum total bile acid

LABORATORY FINDINGS concentration.

A complete biochemical profile, complete blood cell Other liver function tests include fasted preprandial

count, and urinalysis are generally adequate to screen serum total bile acid concentration, postprandial

for abnormalities. serum total bile acid concentration, and basal plasma

NH3 concentration.

Hepatic Abnormalities

Enzyme Activities & Bilirubin. Particular attention Hematologic Abnormalities

should be given to any elevation of hepatobiliary Blood Cells. Nonregenerative anemia due to

enzyme activities and bilirubin: decreased mobilization of systemic iron stores

• Elevated total serum bilirubin concentration has been may be present in dogs with chronic hepatitis;

identified as a negative prognostic indicator.12 regenerative anemia may be present if associated with

• Increased hepatobiliary enzyme activities, such gastrointestinal blood loss. Morphologic erythrocyte

as alanine aminotransferase and aspartate abnormalities due to altered lipoprotein content may

aminotransferase, are consistent with hepatocellular also be seen.

damage. Coagulation. Coagulation status should be

• Variable degrees of elevated hepatobiliary enzyme assessed because altered hemostasis can contribute

activities, such as alkaline phosphatase and gamma- to clinical disease and may affect diagnostic testing

glutamyl transpeptidase, are consistent with options. Available tests are listed in Table 3, but no

cholestasis. individual test predicts clinically significant bleeding

• Disturbances in markers of hepatocellular damage and, thus, evaluation of primary and secondary Learn More

often predominate in dogs with chronic hepatitis, hemostasis is recommended. Abnormalities can

Turn to page 87

with 90% of patients demonstrating elevated result from hepatic synthetic failure, vitamin K to read Canine

serum alanine aminotransferase activity.13 deficiency, disseminated intravascular coagulation, Leptospirosis:

and qualitative or quantitative platelet defects. (Still) An Emerging

Serum hepatobiliary enzyme activities may be

Infection? written by

normal, or only mildly increased, in patients with Serology. Serology for leptospirosis can be Dr. Richard Ford.

end-stage chronic hepatitis; therefore, even mild submitted to determine the potential role of this

elevations may be significant, if persistent and when pathogen.

other potential causes have been excluded. Since dogs

with significant liver disease can be clinically silent, ULTRASONOGRAPHY

in those with elevated liver enzyme activities that persist Complete abdominal ultrasonography is an essential

longer than 4 to 6 weeks, we recommend screening for an component of further diagnostic evaluation

underlying etiology. that allows screening for concurrent disease and

There may be additional evidence of hepatic acquisition of bile.

insufficiency depending on disease severity: • In chronic hepatitis, the liver is variable and can be

• Decreased serum albumin, cholesterol, blood normal upon examination.

urea nitrogen (BUN), glucose (rare), or • Sonographic changes consistent with chronic

hyperbilirubinemia may reflect hepatic insufficiency hepatitis include uniform increases in liver

or end-stage cirrhotic change.

• These changes must be distinguished from Table 3.

different or concurrent abnormalities, such as Coagulation Tests for Chronic Hepatitis*

protein-losing enteropathy, decreased protein • Activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT)

intake, polyuria (increased renal excretion • Buccal mucosal bleeding time (BMBT)

of BUN), or hemolytic anemia (prehepatic • D-dimers

• Fibrinogen

hyperbilirubinemia).

• Platelet count

Liver Function. Specific tests of liver function • Prothrombin time (PT)

are often warranted, but there is no consensus on • Thromboelastography

which liver function test is most appropriate. The * The authors frequently evaluate platelet count, PT, aPTT,

and BMBT to evaluate primary and secondary hemostasis.

most commonly performed test in the U.S. and, in

tvpjournal.com | March/April 2015 | TODAY’S VETERINARY PRACTICE 27

Peer Reviewed Canine Chronic Hepatitis: Diagnosis & Treatment

laparoscopic guidance, or direct visualization during

laparotomy (Figure 1).

Bacterial cholecystitis can result in clinical signs

and clinicopathologic anomalies indistinguishable

from chronic hepatitis and, thus, exclusion of this

disease is an important component of the diagnostic

evaluation.

DIAGNOSTIC LIVER BIOPSY

Liver biopsy is essential for establishing a definitive

diagnosis in dogs suspected of having chronic hepatitis.

Several biopsy techniques are available for acquiring

histology-grade liver tissue; however, fine-needle

FIGURE 1. Laparoscopic-assisted aspiration is NOT adequate for diagnosis of any type

cholecystocentesis permits safe acquisition of of inflammatory liver disease.

bile for diagnostic evaluation. Histopathologic diagnosis of chronic hepatitis

Courtesy Dr. Romy Heilmann, Texas A&M University requires demonstration of the characteristic

components: hepatocellular necrosis or apoptosis,

echogenicity, decreased distinction of portal vein mononuclear or mixed inflammatory cell infiltrate

margins, and normal to small liver size. composed primarily of lymphocytes and plasma cells,

• The liver parenchyma, biliary tree, portal regeneration, and fibrosis.1

vein, and peritoneum should be assessed for • Pattern and distribution of characteristic

abnormalities, acquired shunting, and presence of components of chronic hepatitis are variable.

free peritoneal fluid. • Disease severity is determined by amount of

inflammation present and extent of hepatocellular

CHOLECYSTOCENTESIS necrosis and apoptosis.

Cholecystocentesis to acquire bile for cytologic • Stage of disease is determined by the extent and

evaluation and aerobic/anaerobic bacterial culture and pattern of fibrosis.

sensitivity should be routinely performed in patients • Qualitative increases in copper may be detected

suspected of having chronic hepatitis. This technique with special stains if levels exceed 400 ppm. The

can be safely performed via ultrasound guidance, pattern of copper accumulation can also provide

additional information about the disease process,

with qualitative staining techniques revealing

that:

»» Cholestatic diseases result in periportal (zone 1)

copper accumulation

»» Copper-associated chronic hepatitis results in

centrilobular (zone 3) accumulation.

Percutaneous Ultrasound-Guided Needle Biopsy

Percutaneous ultrasound-guided needle biopsy uses

an automated, semi-automated, or manual biopsy

needle to acquire hepatic tissue. Percutaneous TruCut

(carefusion.com) liver biopsies require ultrasound

guidance and may be limited by a small liver or small

patient size. Particular care should be taken to ensure

adequate sampling (3–6 tissue specimens/samples;

14-gauge for large/medium dogs or 16-gauge for

FIGURE 2. Laparoscopic image of the liver in 7-year-old intact male small dogs).

Labrador retriever with chronic hepatitis and marked fibrosis. Note

Advantages include that the technique can be

gross discoloration and nodular remodeling.

Courtesy Dr. Romy Heilmann, Texas A&M University

performed under sedation, is minimally invasive, and

isolated lesions within the hepatic parenchyma can be

28 Today’s Veterinary Practice | March/April 2015 | tvpjournal.com

CANINE CHRONIC HEPATITIS: DIAGNOSIS & TREATMENT Peer Reviewed

Wedge Biopsy

Wedge biopsy by laparotomy can be performed

by transfixation or biopsy punch. Advantages and

disadvantages of this technique are similar to those

for laparoscopy. Additional consideration for this

technique is degree of invasiveness; however, it can

be combined with other surgical procedures in the

abdomen.

Other Biopsy Techniques

A transjugular liver biopsy technique has been

recently described in dog cadavers but due to the

high potential complication rate, which included

FIGURE 3. Laparoscopic image of liver after

biopsy; demonstrates normal degree of perforations of the liver capsule in 13 of 16 dogs

postprocedural hemorrhage with normal (81%), further studies are needed before this

coagulation. technique can be recommended.14

specifically sampled. Disadvantages include relatively BIOPSY TECHNIQUE & EVALUATION

smaller biopsy samples and inability to control Biopsy Technique

hemorrhage directly. Sampling may be limited if the All techniques suffer from sampling artifact and, thus,

liver or the patient is of multiple samples should be acquired and multiple

small size.

Laparoscopic Biopsy

Laparoscopic liver biopsy

is performed under general

anesthesia, and the liver

is sampled with biopsy

forceps. Gross examination

of the liver and associated

structures and targeted

sampling of multiple

identified lesions can be A B

performed (Figure 2).

After sample acquisition, the

biopsy sites can be visually

inspected for hemorrhage

(Figure 3).

Advantages of this

technique include direct

visualization of the liver;

relatively large tissue

samples; ability to control

hemorrhage directly with

a palpation probe or a C D

hemostatic agent, such as gel FIGURE 4. Corresponding sections of liver tissue show evidence of severe chronic hepatitis

foam; and access to multiple secondary to excess copper accumulation. Note the different features highlighted by the

liver lobes for sampling. respective stains: (A) hematoxylin–eosin staining highlighting inflammatory infiltrate in

portal triad (arrow), (B) Rhodanine staining highlighting copper granules (arrow), (C) Perls’

Disadvantages include need

iron stain highlighting blue iron granules (arrow), and (D) sirius red staining highlighting red

for specialized equipment

collagen fibrils (arrow) (all images: original magnification, 20×).

and specific skills, general Courtesy Dr. John Cullen, North Carolina State University

anesthesia, and cost.

tvpjournal.com | March/April 2015 | TODAY’S VETERINARY PRACTICE 29

Peer Reviewed Canine Chronic Hepatitis: Diagnosis & Treatment

lobes biopsied. A recent study reported that if the liver quantification and aerobic/anaerobic bacterial culture

biopsy specimen contains at least 3 to 12 portal triads, and sensitivity should be considered a routine part of

all biopsy techniques carry a similar diagnostic utility.15 the diagnostic evaluation.

Histopathologic Evaluation THERAPEUTIC APPROACH

Liver tissue samples should be submitted for The initiating factor in most cases of chronic hepatitis

histopathologic evaluation (Figure 4, page 29): remains unknown. General principles guiding the

• Routine stains include hematoxylin–eosin. treatment of idiopathic canine chronic hepatitis

• Special stains to characterize fibrosis or cirrhotic include (Table 4):

changes include Sirius red, Masson trichrome stain, • Immunosuppressive therapy to resolve or control

van Gieson stain, and the reticulin stain according the inflammatory process

to Gordon and Sweet.1 • Antioxidant therapy to prevent oxidative stress

• Additional stains may also be used to detect certain • Antifibrotic therapy to inhibit fibrosis.

substances, such as: Available evidence suggests that humans

»» Copper (rubeanic acid or rhodanine stain) and dogs have similar mechanisms for hepatic

»» Iron (Perls’ iron stain) fibrosis in chronic hepatitis; thus, most treatment

»» Glycogen (periodic acid–Schiff stain). recommendations are extrapolated from the human

literature.16,17 Compliance is essential for treatment

Tissue Preparation success. Therefore, facilitating drug administration

Additional special stains, immunohistochemical by limiting the number of medications to those most

techniques, and polymerase chain reaction techniques appropriate is prudent.

can be performed on formalin-fixed tissue but provide

better results in unfixed frozen tissue; therefore, an Symptomatic Therapy

additional biopsy specimen should be freshly frozen. Treatment of canine chronic hepatitis in most cases

Approximately 1 gram of fresh liver tissue in a is symptomatic, supportive, and aimed at slowing

serum blood tube is required for atomic absorption progression of fibrosis (Table 4):

analysis; however, formalin-fixed tissue may also • Nausea: Antiemetic therapy

be submitted for copper quantification. Copper • Gastrointestinal ulceration: Appropriate antacid

therapy

• Portal hypertension: Inhibition of renin-

Biopsy Coagulation Concerns

angiotensin system

Hemorrhage is a risk of all liver biopsy techniques

Concerns & and, thus, assessment of coagulation status is • Hepatic encephalopathy: Appropriate dietary,

required despite the relative insensitivity of the probiotic, antimicrobial, and lactulose therapy.

Contra- available coagulation measures for predicting

Exceptions to limiting treatment to symptomatic

clinically significant bleeding. Postprocedural

indications monitoring for hemorrhage is advised, with therapy include:

serial assessment of packed cell volume. Patients • Copper-associated chronic hepatitis: Specific

should be kept inactive for 6 to 8 hours after treatment includes low-copper diet, copper

biopsy collection.

chelator, and potentially increased alimentary zinc

Biopsy Contraindications • Infection-associated chronic hepatitis: Appropriate

Coagulation testing for laboratory analysis should use of antimicrobial agents

be performed no more than 24 hours before liver • Drug-associated chronic hepatitis: Withdrawal of drug.

biopsy because coagulation variables can change

quickly in dogs with chronic hepatitis.

Immunosuppressive Therapy

Sampling of the liver is contraindicated if a Corticosteroid therapy with prednisone/prednisolone

severe coagulopathy is present (prolonged is the most common immunosuppressive medication

BMBT, platelet count < 80,000, PT/partial

used in dogs with chronic hepatitis. It has been

thromboplastin time prolonged > 1.5–2×

normal). In some patients, however, coagulation shown to prolong survival, improve hepatic histologic

measurements can be corrected with vitamin changes, and induce remission.18,19 Adjunctive

K supplementation, platelet transfusion, immunosuppressive therapy, such as leflunomide, can

desmopressin acetate, or administration of fresh

frozen plasma.

be added for steroid-sparing effects and/or additional

immunosuppression to achieve disease remission.

In our opinion, remission is best determined by

30 Today’s Veterinary Practice | March/April 2015 | tvpjournal.com

Canine Chronic Hepatitis: Diagnosis & Treatment Peer Reviewed

repeat liver biopsy. Serial monitoring every 2 weeks normalization in alanine transaminase activity is often

for normalization or marked reduction of alanine used in lieu of a second liver biopsy.

transaminase activity can be used as a surrogate

marker of disease remission and to indicate repeat Antioxidant Therapy

liver biopsy. Glucocorticoids frequently result in The use of antioxidants as an adjunct to standard

variable increases in alanine transaminase, alkaline therapy is advocated to reduce hepatic injury and

phosphatase, and gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase fibrosis in dogs with chronic hepatitis.20

activity; therefore, a relative significant decrease or • Studies of human patients with chronic hepatitis

Table 4.

Common Drugs & Nutraceuticals for Management of Canine Chronic Hepatitis

DRUG NAME Dose INDICATION/COMMENTS

Azathioprine 2 mg/kg PO Q 24 H for 10–14 D; then • Anti-inflammatory

Q 48 H • Immunosuppressive (not preferred)

Cyclosporine 5–10 mg/kg PO Q 12 H • Anti-inflammatory

• Immunosuppressive

Lactulose 0.1–0.5 mL/kg PO Q 8–12 H • Decreases ammonia absorption

Leflunomide 4–6 mg/kg PO Q 24 H • Antifibrotic

• Anti-inflammatory

• Immunosuppressive

Losartan 0.25–0.5 mg/kg PO Q 24 H • Antifibrotic

Metronidazole 8–10 mg/kg PO Q 12 H • Anti-inflammatory

• Decreases ammonia-producing bacteria

Mycophenolate 10–12 mg/kg PO Q 24 H • Anti-inflammatory

• Immunosuppressive

Neomycin 22 mg/kg PO Q 8 H • Decreases ammonia-producing bacteria

Omeprazole 1–2 mg/kg PO Q 12 H • Antacid

Penicillamine 10–15 mg/kg PO Q 12 H; administer • Antioxidant

30–60 min before meals • Copper chelator

Prednisone/ 1–2 mg/kg PO Q 24 H until 2–3 weeks • Antifibrotic

prednisolone after clinical remission; then slowly • Anti-inflammatory

taper to lowest effective dose • Immunosuppressive

Probiotic therapy Per labeled instructions • Displaces ammonia-producing bacteria

S-adenosylmethionine 20 mg/kg PO Q 24 H in fasted patient • Antifibrotic

to increase absorption • Anti-inflammatory

Silymarin/silybinin 20–50 mg/kg PO Q 24 H • Antioxidant

Spironolactone 1–2 mg/kg PO Q 12 H • Diuretic for portal hypertension and ascites

Sucralfate 0.5–1 g PO Q 8 H (slurry); administer • Anti-ulcer therapy

at least 2 H before or after all other

medications

Trientine 10–15 mg/kg PO Q 12 H • Copper chelator

(expensive, with few clinical data in dogs)

Ursodeoxycholic acid 10–15 mg/kg PO Q 24 H; dose can be • Anti-inflammatory

divided Q 12 H • Antioxidant

• Choleretic

Vitamin E 250–400 IU/day PO • Antioxidant

Vitamin K 0.5–1.5 mg/kg SC or PO Q 24 H • Deficiency

Zinc (elemental zinc) 10 mg/kg PO Q 12 H • Antifibrotic

• Antioxidant

tvpjournal.com | March/April 2015 | Today’s Veterinary Practice 31

Peer Reviewed CANINE CHRONIC HEPATITIS: DIAGNOSIS & TREATMENT

have documented that those with persistent Protein Restriction

oxidative stress benefit from antioxidant Protein restriction should be limited to the maximum

supplementation.21–24 tolerated level that prevents signs of hepatic

• Glutathione, a potent antioxidant, has encephalopathy; therefore, it may not be appropriate

been reported to be decreased in dogs with to start with the severe protein restriction provided

necroinflammatory liver disease.25 by a prescription liver diet.

• Vitamin E, S-adenosylmethionine, silibinin, If protein restriction is required, diets that contain

N-acetylcysteine, and ursodeoxycholic acid are moderate amounts of protein, such as prescription

antioxidants commonly used as ancillary treatments in renal diets and geriatric diets, may be suitable

dogs with chronic hepatitis. In various studies, these alternatives to a prescription liver diet. Diets may also

nutraceuticals show inhibition of hepatic stellate cell be supplemented with high-quality protein, such as

activation, protection of hepatocytes from apoptosis, egg whites.

and attenuation of experimental liver fibrosis.26-28 A consultation with a board-certified veterinary

• Veterinarians should be aware, however, that nutritionist may be necessary for patients with

limited to no evidence supports the general use comorbid conditions or those in which homemade

of antioxidants in preventing or treating chronic diets are indicated.

hepatitis, and few studies document beneficial

effects of these antioxidants in vivo. Anticopper Therapy

Anticopper drug therapy is generally reserved for

Antifibrotic Therapy cases with documented primary or secondary excess

There is no standard treatment for hepatic fibrosis. copper accumulation.

Experimental studies have identified targets to inhibit • The chelator, penicillamine, is typically used, and

fibrosis in rodents, but the efficacy of most treatments has additional anti-inflammatory and antifibrotic

has not been investigated in dogs.17 Also, the need effects.

to perform serial liver biopsies to accurately assess • Trientine can serve as an alternative if penicillamine

changes in liver fibrosis makes studies documenting is not tolerated.

treatment efficacy difficult. • Copper chelators should be used for 3 to 6 months

The development of reliable noninvasive markers before a second liver biopsy is performed to ensure

for liver fibrosis may enhance the management of adequate disease remission and normalization of

these patients. Drugs with theoretical and limited copper levels; then followed by zinc therapy, if

experimental evidence for the treatment of fibrosis appropriate to prevent copper reaccumulation.

include colchicine, corticosteroids, penicillamine, • Zinc toxicity can result from oral zinc

zinc, angiotensin inhibitors, and angiotensin-receptor administration; periodic monitoring of blood

blockers.13,19,29,30 zinc concentration is recommended with use of

However, the clinical utility of colchicine for the elemental zinc therapy.

reversal or prevention of hepatic fibrosis is limited,

and because of the associated adverse effects, which PROGNOSIS

include vomiting, diarrhea, and inappetance, we do The prognosis for dogs with chronic hepatitis varies.

not recommend routine use of this drug. Median survival durations of 18.3 to 36.4 months

have been reported.

However, patients with

YURI LAWRENCE JÖRG sTEINER hypoalbuminemia,

Yuri Lawrence, DVM, MA, MS, Diplo- Jörg Steiner, MedVet, DrMedVet, PhD, AGAF, hypoglycemia,

mate ACVIM, is enrolled in the Texas Diplomate ACVIM and ECVIM, is a professor in prolonged clotting

A&M University Gastrointestinal PhD the Departments of Small Animal Medicine and

program and also serves as a senior Surgery, and Veterinary Pathobiology, as well as

times, bridging fibrosis,

clinician at the institution’s small animal the director of the Gastrointestinal Laboratory, at and ascites have shorter

hospital. Dr. Lawrence received his DVM

from Tufts University; then completed

Texas A&M University. He was recognized as a survival times.2,11,18,31

Fellow of the American Gastroenterology Asso-

an MA in anatomy and neurobiology at Early diagnosis

Boston University, an internship in small ciation. He received his veterinary degrees from

Ludwig-Maximilians University, Munich, Germa- and intervention are

animal medicine and surgery at North

Carolina State University, and a resi- ny; then completed an internship at University of important for successful

dency in small animal internal medicine Pennsylvania, residency in small animal internal treatment of dogs

and MS in veterinary science at Oregon medicine at Purdue University, and his PhD at

State University. Texas A&M University.

with chronic hepatitis

because patients with

32 TODAY’S VETERINARY PRACTICE | March/April 2015 | tvpjournal.com

Canine Chronic Hepatitis: Diagnosis & Treatment Peer Reviewed

end-stage disease and signs of decompensated liver function prednisolone treatment in canine chronic hepatitis. Vet Q 2013; 33:113-120.

20. Center SA. Chronic liver disease: Current concepts of disease mechanisms. J

have a poorer prognosis. Small Anim Pract 1999; 40:106-114.

21. Chiou YL, Chen YH, Ke T, et al. The effect of increased oxidative stress and

IN SUMMARY ferritin in reducing the effectiveness of therapy in chronic hepatitis C patients.

Clin Biochem 2012; 45:1389-1393.

There is still much unknown about the etiology and treatment 22. Farias MS, Budni P, Ribeiro CM, et al. Antioxidant supplementation attenuates

of chronic hepatitis in dogs. The World Small Animal oxidative stress in chronic hepatitis C patients. Gastroenterol Hepatol 2012;

35:386-394.

Veterinary Association guidelines1 provide an important 23. Yadav D, Hertan HI, Schweitzer P, et al. Serum and liver micronutrient

scaffolding of the etiology and treatment of this disease antioxidants and serum oxidative stress in patients with chronic hepatitis C.

that should build on our current knowledge and facilitate Am J Gastroenterol 2002; 97:2634-2639.

24. Venturini D, Simao AN, Barbosa DS, et al. Increased oxidative stress,

multicenter studies, with the hope of improving patient decreased total antioxidant capacity, and iron overload in untreated patients

survival and outcome. with chronic hepatitis C. Dig Dis Sci 2010; 55:1120-1127.

25. Center SA, Warner KL, Erb HN. Liver glutathione concentrations in dogs and

cats with naturally occurring liver disease. Am J Vet Res 2002; 63:1187-1197.

aPTT = activated partial thromboplastin time; BMBT = 26. Friedman SL, Roll FJ, Boyles J, et al. Hepatic lipocytes: The principal

buccal mucosal bleeding time; BUN = blood urea nitrogen; collagen-producing cells of normal rat liver. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1985;

82:8681-8685.

PT = prothrombin time 27. Center SA. Metabolic, antioxidant, nutraceutical, probiotic, and herbal therapies

relating to the management of hepatobiliary disorders. Vet Clin North Am Small

Anim Pract 2004; 34:67-172.

References

28. Webster CR, Cooper J. Therapeutic use of cytoprotective agents in canine

1. Routhuizen J, World Small Animal Veterinary Association, Liver

and feline hepatobiliary disease. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 2009;

Standardization Group, et al. WSAVA Standards for Clinical and Histological

39(3):631-652.

Diagnosis of Canine and Feline Liver Disease. Edinburgh, New York: Saunders

29. Watson PJ. Chronic hepatitis in dogs: A review of current understanding of the

Elsevier, 2006.

aetiology, progression, and treatment. Vet J 2004; 167:228-241.

2. Poldervaart JH, Favier RP, Penning LC, et al. Primary hepatitis in dogs: A

30. Lubel JS, Herath CB, Burrell LM, et al. Liver disease and the renin-angiotensin

retrospective review (2002-2006). J Vet Intern Med 2009; 23:72-80.

system: Recent discoveries and clinical implications. J Gastroenterol Hepatol

3. Schulze C, Baumgartner W. Nested polymerase chain reaction and in situ

2008; 23:1327-1338.

hybridization for diagnosis of canine herpesvirus infection in puppies. Vet

31. Sevelius E. Diagnosis and prognosis of chronic hepatitis and cirrhosis in dogs.

Pathol 1998; 35:209-217.

J Small Anim Pract 1995; 36:521-528.

4. Chouinard L, Martineau D, Forget C, et al. Use of polymerase chain reaction

and immunohistochemistry for detection of canine adenovirus type 1 in

formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded liver of dogs with chronic hepatitis or

cirrhosis. J Vet Diagn Invest 1998; 10:320-325.

5. Fox JG, Drolet R, Higgins R, et al. Helicobacter canis isolated from a dog liver

with multifocal necrotizing hepatitis. J Clin Microbiol 1996; 34:2479-2482.

6. Bunch SE. Hepatotoxicity associated with pharmacologic agents in dogs and

cats. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 1993; 23:659-670.

7. Bishop L, Strandberg JD, Adams RJ, et al. Chronic active hepatitis in dogs

associated with leptospires. Am J Vet Res 1979; 40:839-844.

8. Sevelius E, Andersson M, Jonsson L. Hepatic accumulation of alpha-1-

antitrypsin in chronic liver disease in the dog. J Comp Pathol 1994; 111:401-

412.

9. Poitout F, Weiss DJ, Armstrong PJ. Cell-mediated immune responses to liver

membrane protein in canine chronic hepatitis. Vet Immunol Immunopathol

1997; 57:169-178.

10. Favier RP. Idiopathic hepatitis and cirrhosis in dogs. Vet Clin North Am Small

Anim Pract 2009; 39:481-488.

11. Raffan E, McCallum A, Scase TJ, et al. Ascites is a negative prognostic

indicator in chronic hepatitis in dogs. J Vet Intern Med 2009; 23:63-66.

12. Gomez Selgas A, Bexfield N, Scase TJ, et al. Total serum bilirubin as a negative

prognostic factor in idiopathic canine chronic hepatitis. J Vet Diagn Invest

2014; 26:246-251.

13. Center SA. Chronic hepatitis, cirrhosis, breed-specific hepatopathies, copper

storage hepatopathy, suppurative hepatitis, granulomatous hepatitis, and

idiopathic hepatic fibrosis. In Guilford WG, Center SA, Strombeck D (eds):

Strombeck’s Small Animal Gastroenterology, 3rd ed. Philadephia: Saunders, 1996.

14. Levien AS, Weisse C, Donovan TA, et al. Assessment of the efficacy and

potential complications of transjugular liver biopsy in canine cadavers. J Vet

Intern Med 2014; 28:338-345.

15. Kemp SD, Zimmerman KL, Panciera DL, et al. A comparison of liver

sampling techniques in dogs. J Vet Intern Med 2014 [epub ahead of print].

16. Boisclair J, Dore M, Beauchamp G, et al. Characterization of the inflammatory

infiltrate in canine chronic hepatitis. Vet Pathol 2001; 38:628-635.

17. Bataller R, Brenner DA. Hepatic stellate cells as a target for the treatment of

liver fibrosis. Semin Liver Dis 2001; 21:437-451.

18. Strombeck DR, Miller LM, Harrold D. Effects of corticosteroid treatment on

survival time in dogs with chronic hepatitis: 151 cases (1977-1985). JAVMA

1988; 193:1109-1113.

19. Favier RP, Poldervaart JH, van den Ingh TS, et al. A retrospective study of oral

tvpjournal.com | March/April 2015 | Today’s Veterinary Practice 33

You might also like

- Pathology of Alcoholic Liver DiseaseDocument7 pagesPathology of Alcoholic Liver DiseasehghNo ratings yet

- Cholecystitis Concept MapDocument4 pagesCholecystitis Concept Mapnursing concept maps100% (7)

- Revision Notes Dr. A. MowafyDocument222 pagesRevision Notes Dr. A. MowafyMohammed RisqNo ratings yet

- DR - Dilip MMS GIT NotesDocument263 pagesDR - Dilip MMS GIT NotesKoushik Sharma AmancharlaNo ratings yet

- Comparative Animal AnatomyDocument324 pagesComparative Animal AnatomyMohammed Anuz80% (5)

- Chronic Liver Disease (Tutorial)Document44 pagesChronic Liver Disease (Tutorial)Hannah HalimNo ratings yet

- Hepatobiliary Disorders: Katrina Saludar Jimenez, R. NDocument42 pagesHepatobiliary Disorders: Katrina Saludar Jimenez, R. NKatrinaJimenezNo ratings yet

- Acute Liver Failure EASL CPGDocument57 pagesAcute Liver Failure EASL CPGFatima Medriza DuranNo ratings yet

- Azolla Success StoryDocument3 pagesAzolla Success StoryThamil ArasanNo ratings yet

- Markiii RM PDFDocument285 pagesMarkiii RM PDFveehneeNo ratings yet

- CKD Case StudyDocument27 pagesCKD Case StudyMary Rose Vito100% (1)

- 06.2 Inborn Error of Metabolism - Iii B - Trans PDFDocument10 pages06.2 Inborn Error of Metabolism - Iii B - Trans PDFAshim AbhiNo ratings yet

- Azolla Study ReportDocument26 pagesAzolla Study ReportThamil ArasanNo ratings yet

- New PPT For HepatitisDocument88 pagesNew PPT For HepatitisPriya100% (1)

- Week 13 NCMB 312 Lect NotesDocument18 pagesWeek 13 NCMB 312 Lect NotesAngie BaylonNo ratings yet

- Imunologie MedicalaDocument224 pagesImunologie MedicalaTo Ma100% (10)

- Duck PDFDocument21 pagesDuck PDFThamil ArasanNo ratings yet

- Hepatobiliary Disorders: Katrina Saludar Jimenez, R. NDocument42 pagesHepatobiliary Disorders: Katrina Saludar Jimenez, R. NreykatNo ratings yet

- Termek Cikk GY0045 1513869631Document7 pagesTermek Cikk GY0045 1513869631ItsAnimal DudeNo ratings yet

- Fulminant Hepatic Failure (FHF) (Acute Liver Failure (ALF) ) : DR / Reyad AlfakyDocument108 pagesFulminant Hepatic Failure (FHF) (Acute Liver Failure (ALF) ) : DR / Reyad AlfakypadmaNo ratings yet

- 62 DiarrheaChronic MGHG MIMG MFM 20161229Document10 pages62 DiarrheaChronic MGHG MIMG MFM 20161229Wei HangNo ratings yet

- Sas S9Document9 pagesSas S9Ralph Louie ManagoNo ratings yet

- 1-Differential Diagnosis of Vomiting 2021 PsáderR SAM3Document28 pages1-Differential Diagnosis of Vomiting 2021 PsáderR SAM3Simay KızılkayaNo ratings yet

- Acute Liver FailureDocument53 pagesAcute Liver FailureMonesh-BhaskaranNo ratings yet

- Prolonged Cholestasis Due To Hepatitis A Virus Infection in A Young Adolescent Male With A Known Case of Hemoglobin E Disease: Early Response To Steroid TherapyDocument4 pagesProlonged Cholestasis Due To Hepatitis A Virus Infection in A Young Adolescent Male With A Known Case of Hemoglobin E Disease: Early Response To Steroid TherapyBOHR International Journal on GastroenterologyNo ratings yet

- Cushings-Pt2 (2021 - 03 - 03 15 - 11 - 26 UTC)Document8 pagesCushings-Pt2 (2021 - 03 - 03 15 - 11 - 26 UTC)magloria77No ratings yet

- Jaundice and Ascites Group ProjectDocument15 pagesJaundice and Ascites Group ProjectJosiah Noella BrizNo ratings yet

- Review: Liver Dysfunction in Critical IllnessDocument17 pagesReview: Liver Dysfunction in Critical IllnessRoger Ludeña SalazarNo ratings yet

- Sa Jun 2018 PDFDocument6 pagesSa Jun 2018 PDFdpcamposhNo ratings yet

- 3939 Whitcomb CRNP AGA Aug2014Document27 pages3939 Whitcomb CRNP AGA Aug2014Leopoldo MagañaNo ratings yet

- Acute Glomerular Nephritis V.S Nephrotic SyndromeDocument4 pagesAcute Glomerular Nephritis V.S Nephrotic SyndromeYoussef AliNo ratings yet

- NCMB312 LECTURE: Communicable Diseases, Cancer, Nursing CareDocument63 pagesNCMB312 LECTURE: Communicable Diseases, Cancer, Nursing CareRose Ann CammagayNo ratings yet

- CLD FinalDocument17 pagesCLD FinalHervis FantiniNo ratings yet

- Gastrointestinal System (Paper-V) PBQs 2018 KU With SolutionsDocument6 pagesGastrointestinal System (Paper-V) PBQs 2018 KU With SolutionsCatalyst NepalNo ratings yet

- LiverDocument30 pagesLiverNisini ImanyaNo ratings yet

- Case Study in Vesicovaginal FistulaDocument14 pagesCase Study in Vesicovaginal FistulaIvory100% (4)

- Model Test-1 SolveDocument20 pagesModel Test-1 SolveRaihanShaheedNo ratings yet

- I Patient Assessment Data BaseDocument12 pagesI Patient Assessment Data BaseJanice_Fernand_1603No ratings yet

- Pharmacology LaqDocument11 pagesPharmacology Laqravindra b kadamNo ratings yet

- Final Neonatal JaundiceDocument47 pagesFinal Neonatal JaundiceArati JhaNo ratings yet

- Management of Severe Malaria in Pregnancy-Final 2Document30 pagesManagement of Severe Malaria in Pregnancy-Final 2ocencolumbusNo ratings yet

- Viral Diseases of Alimentary Canal in CaninesDocument37 pagesViral Diseases of Alimentary Canal in CaninesNavneet BajwaNo ratings yet

- Pediatric Hepatitis - General PrinciplesDocument52 pagesPediatric Hepatitis - General Principlesesra yulianaNo ratings yet

- Case Presentation Febrile Neutropenia NizarDocument25 pagesCase Presentation Febrile Neutropenia NizarNizar IJNo ratings yet

- Elevated Deoxycholic Acid and Idiopathic Recurrent Acute PancreatitisDocument3 pagesElevated Deoxycholic Acid and Idiopathic Recurrent Acute PancreatitisMaria LimaNo ratings yet

- Management of DiarrheaDocument12 pagesManagement of DiarrheaHammo Ez AldienNo ratings yet

- Viral Hepatitis and Alcoholic Liver Disease: Prepared By: Azhi Omer - F190219 Supervised By: Dr. Truska FaraidunDocument29 pagesViral Hepatitis and Alcoholic Liver Disease: Prepared By: Azhi Omer - F190219 Supervised By: Dr. Truska FaraidunMustafa Salam M.NooriNo ratings yet

- 2017-2018 - GI Infectious DiseasesDocument57 pages2017-2018 - GI Infectious Diseasesbahadar94No ratings yet

- 2.4.4.3D Reye's Syndrome - Dr. SaptinoDocument48 pages2.4.4.3D Reye's Syndrome - Dr. Saptinonawal asmadiNo ratings yet

- Analytical Study of Pancreatitis in DogsDocument4 pagesAnalytical Study of Pancreatitis in DogsMaria Isabel GomezNo ratings yet

- Minimizing Bleeding: Late SignDocument12 pagesMinimizing Bleeding: Late SignMatth N. ErejerNo ratings yet

- Alf Ajay AgadeDocument84 pagesAlf Ajay AgadeVinay PatilNo ratings yet

- Hepatitis GeneralDocument14 pagesHepatitis GeneralMarysol UlloaNo ratings yet

- 04 FCH Acute GastroenteritisDocument9 pages04 FCH Acute GastroenteritisClar MoniquezNo ratings yet

- Antibiotics by Clinical CasesDocument59 pagesAntibiotics by Clinical CasesNikNo ratings yet

- PYELONEPHRITISDocument1 pagePYELONEPHRITISgreskpremium8No ratings yet

- JAUNDICE - Role PlayDocument2 pagesJAUNDICE - Role Playnathanaellee92No ratings yet

- Jaundice 160318164012Document47 pagesJaundice 160318164012Ritik MishraNo ratings yet

- Harriet Lane Handbook 21st Ed 2018-401-600Document200 pagesHarriet Lane Handbook 21st Ed 2018-401-600nguyễn vjNo ratings yet

- Vit B (FSW)Document2 pagesVit B (FSW)khelxoNo ratings yet

- Top 5 Breed-Associated Biochemical AbnormalitiesDocument5 pagesTop 5 Breed-Associated Biochemical AbnormalitiesCabinet VeterinarNo ratings yet

- Ptyalism & Pseudoptyalism - Allen, JulieDocument2 pagesPtyalism & Pseudoptyalism - Allen, JulieJuanMartínezNo ratings yet

- RCPCH guidance on rare inflammatory syndrome in childrenDocument6 pagesRCPCH guidance on rare inflammatory syndrome in childrenMario TGNo ratings yet

- Liver Focus 20Document7 pagesLiver Focus 20Sanja CirkovicNo ratings yet

- Case Study Tumor LysisDocument28 pagesCase Study Tumor Lysisapi-653850652No ratings yet

- Feline BabesiosisDocument8 pagesFeline BabesiosisPretty PeterNo ratings yet

- Unit - I: Managee's Potential Is Determined When A Set of Tasks Are Assigned To Him. It IsDocument233 pagesUnit - I: Managee's Potential Is Determined When A Set of Tasks Are Assigned To Him. It IsAmit BaruahNo ratings yet

- How Estrogen Protects BonesDocument7 pagesHow Estrogen Protects BonesThamil ArasanNo ratings yet

- 5 OzkanDocument6 pages5 OzkanThamil ArasanNo ratings yet

- Interglobe Aviation LTDDocument2 pagesInterglobe Aviation LTDThamil ArasanNo ratings yet

- Agriculture Knowledge Management: Advance Training Program OnDocument68 pagesAgriculture Knowledge Management: Advance Training Program OnThamil ArasanNo ratings yet

- Equine ExamDocument85 pagesEquine Examياسر قاتل البزونNo ratings yet

- Anesthesia Guidelines For Dogs and CatsDocument9 pagesAnesthesia Guidelines For Dogs and CatsNatalie KingNo ratings yet

- How 20to 20perform 20a 20physical 20exam 20in 20your 20horseDocument50 pagesHow 20to 20perform 20a 20physical 20exam 20in 20your 20horseThamil ArasanNo ratings yet

- Ivra Abstracts 2012Document42 pagesIvra Abstracts 2012Thamil ArasanNo ratings yet

- Byagagaire - Xylazine Hydrochloride and Ketamine Hydrochloride Combinations For General Anaesthesia in SheepDocument182 pagesByagagaire - Xylazine Hydrochloride and Ketamine Hydrochloride Combinations For General Anaesthesia in SheepThamil ArasanNo ratings yet

- Infection and ImmunityDocument36 pagesInfection and ImmunityThamil ArasanNo ratings yet

- 3rd Yr CFC Handbook - 2 - Final 2010-11Document16 pages3rd Yr CFC Handbook - 2 - Final 2010-11Barbara LiNo ratings yet

- Anatomy of The Equine FootDocument14 pagesAnatomy of The Equine FootEdmilson Daneze100% (1)

- All Accounts Balance Details: S. No. Account Number Account Type Branch Rate of Interest (% P.a.) BalanceDocument1 pageAll Accounts Balance Details: S. No. Account Number Account Type Branch Rate of Interest (% P.a.) BalanceThamil ArasanNo ratings yet

- Bone Marrow Sampling: Bone Marrow Cytology (Aspiration) Vs Histology (Core Biopsy)Document5 pagesBone Marrow Sampling: Bone Marrow Cytology (Aspiration) Vs Histology (Core Biopsy)Thamil ArasanNo ratings yet

- Hanuman Chalisa Lyrics in Tamil Font PDFDocument4 pagesHanuman Chalisa Lyrics in Tamil Font PDFThamil ArasanNo ratings yet

- Caesarean SectionDocument1 pageCaesarean SectionThamil ArasanNo ratings yet

- Duck Housing and ManagementDocument7 pagesDuck Housing and ManagementThamil ArasanNo ratings yet

- Adoption of Azolla Cultivation Technology in The Farmers' Field: An AnalysisDocument7 pagesAdoption of Azolla Cultivation Technology in The Farmers' Field: An AnalysisThamil ArasanNo ratings yet

- AO - Dental Prophylaxis in A DogDocument5 pagesAO - Dental Prophylaxis in A DogThamil ArasanNo ratings yet

- MYD - Hematochezia in A DogDocument5 pagesMYD - Hematochezia in A DogThamil ArasanNo ratings yet

- Imcrj 9 241Document5 pagesImcrj 9 241Thamil ArasanNo ratings yet

- Azolla Cultivation and Feeding LivestockDocument1 pageAzolla Cultivation and Feeding LivestockThamil ArasanNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0168827820304700 MainDocument11 pages1 s2.0 S0168827820304700 MainHadi KuriryNo ratings yet

- Complicaciones y Costos de La Biopsia HepaticaDocument9 pagesComplicaciones y Costos de La Biopsia HepaticaYonatan Merchant PerezNo ratings yet

- Non Invasive Imaging in NASHDocument3 pagesNon Invasive Imaging in NASHParul SoodNo ratings yet

- Fibroscan Interpretation - Guide 2020Document2 pagesFibroscan Interpretation - Guide 2020Faisal BaigNo ratings yet

- Hepatitis BDocument61 pagesHepatitis BMichael AmandyNo ratings yet

- PAPAS Predict Liver FibrosisDocument7 pagesPAPAS Predict Liver Fibrosisemilya007No ratings yet

- Sammons 2014Document5 pagesSammons 2014viviana castillo VanegasNo ratings yet

- Cirrosis BMJDocument91 pagesCirrosis BMJJuan Luis Nuñez AravenaNo ratings yet

- Noninvasive Assessment of Hepatic Fibrosis - Overview of Serologic Tests and Imaging Examinations - UpToDateDocument35 pagesNoninvasive Assessment of Hepatic Fibrosis - Overview of Serologic Tests and Imaging Examinations - UpToDatepopasorinemilianNo ratings yet

- Portal HypertensionDocument13 pagesPortal HypertensionCiprian BoesanNo ratings yet

- Liver Curs 2009Document215 pagesLiver Curs 2009Mohammad_Islam87No ratings yet

- The Perils of Fatty Liver Disease: Linical Aboratory EwsDocument20 pagesThe Perils of Fatty Liver Disease: Linical Aboratory EwsamirohkurniatiNo ratings yet

- Editorial Commentary On The Indian Journal of Gastroenterology May-June 2020Document3 pagesEditorial Commentary On The Indian Journal of Gastroenterology May-June 2020sivagiri.pNo ratings yet

- The Almost-Normal Liver Biopsy: Presentation, Clinical Associations, and OutcomeDocument7 pagesThe Almost-Normal Liver Biopsy: Presentation, Clinical Associations, and OutcomeAntonio RolonNo ratings yet

- Download ebook Scheuers Liver Biopsy Interpretation Pdf full chapter pdfDocument67 pagesDownload ebook Scheuers Liver Biopsy Interpretation Pdf full chapter pdfwilliam.balasco829100% (23)

- Liver BiopsyDocument4 pagesLiver BiopsyLouis FortunatoNo ratings yet

- Cirrhosis in Adults - Etiologies, Clinical Manifestations, and Diagnosis - UpToDate PDFDocument33 pagesCirrhosis in Adults - Etiologies, Clinical Manifestations, and Diagnosis - UpToDate PDFDonto KonoNo ratings yet

- Guidelines On Prevention of Bleeding and Thrombosis in Cirrhosis-1Document34 pagesGuidelines On Prevention of Bleeding and Thrombosis in Cirrhosis-1labertoNo ratings yet

- Hepatomegali in Infant and Children - Pediatrics in Review-2000-Wolf-303-10Document10 pagesHepatomegali in Infant and Children - Pediatrics in Review-2000-Wolf-303-10Reddy LufyanNo ratings yet

- Hepatic, Pancreatic, and Rare Gastrointestinal Complications of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Therapy - UpToDateDocument29 pagesHepatic, Pancreatic, and Rare Gastrointestinal Complications of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Therapy - UpToDatemayteveronica1000No ratings yet

- Liver Biopsy: Mary Raina Angeli Fujiyoshi, MDDocument10 pagesLiver Biopsy: Mary Raina Angeli Fujiyoshi, MDRaina FujiyoshiNo ratings yet

- PIIS019096222030284XDocument42 pagesPIIS019096222030284XSafira Rosyadatul AissyNo ratings yet

- Case 4 - 2023Document11 pagesCase 4 - 2023Katherine VadilloNo ratings yet

- Europass Curriculum Vitae: Personal Information Popescu Simona-AlinaDocument11 pagesEuropass Curriculum Vitae: Personal Information Popescu Simona-AlinaTanveerNo ratings yet

- Metabolism and EndocrineDocument156 pagesMetabolism and EndocrineGren May Angeli MagsakayNo ratings yet

- Liver Fibrosis A Compilation On The Biomarkers StaDocument17 pagesLiver Fibrosis A Compilation On The Biomarkers Stamy accountNo ratings yet

- FibroscanDocument3 pagesFibroscanAri WirantariNo ratings yet

- Nurc Gastrointestinal Hepatobiliary & Neurological Nursing: Masmunaa Hassan 19 September 2017Document29 pagesNurc Gastrointestinal Hepatobiliary & Neurological Nursing: Masmunaa Hassan 19 September 2017Jakub KubaNo ratings yet

- Ferritin As An Indices of Body Iron Stores and Acute Myocardeal Infarction in DiabeticsDocument58 pagesFerritin As An Indices of Body Iron Stores and Acute Myocardeal Infarction in DiabeticsJagannadha Rao PeelaNo ratings yet