Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Amatuer Woodworker

Uploaded by

v00d00bluesCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Amatuer Woodworker

Uploaded by

v00d00bluesCopyright:

Available Formats

Amateur Woodworker: Archive

Archive

Vol III, Issue 4. August/September 1999

Baby Changing Table

Baby changing tables are a wonderful - yet expensive - addition to any nursery.

With that in mind we set about building a baby changing table that would provide

a strong combination of practicality and price. The resulting table has subsequently

been "battle-tested" for the past month and has stood up to the demands of both

mother and baby. Even better, when your baby (finally) outgrows the need for

diapers, the changing table can be used as a children's chest of drawers. Note that

the baby changing table does not have a rail around the top. Instead, it is designed

to accommodate one of the standard curved foam changing pads.

Paper Towel Holder

This is a quick and easy project for anyone who is fed-up with plastic paper towel

holders which never seem to work as well as they should. The project should take

less than two hours to complete from start to finish and is a great addition to any

kitchen or workshop.

Vol III, Issue 3. June/July 1999

TV Cabinet

With this project we are revisiting an earlier theme: how to make a TV (and its

associated VCR, Cable box and other paraphernalia) less intrusive in a fairly small

room. While the popular approach is typically to hide everything behind a large

entertainment center, we remain unconvinced that this is the best approach.

Instead, we offer the following TV solution that leaves the television in full view

while hiding all of the other equipment. What makes this a really clever solution is

the use of an infrared repeater device that allows the viewer to operate the cable

box and VCR with the doors closed.

Simple Corner Shelf

This corner shelves project is a very simple weekend project. The shelves are

made out of plywood with cheap pine used as the edging to give the effect of a

thicker, more solid type of wood (as well as to provide a useful lip to stop things

getting knocked off too easily). The longest part of this construction by far is the

painting. As such, this is a project that absolutely anyone can take on.

http://www.am-wood.com/archive/archive.html (1 of 11) [11/3/2003 1:37:10 à«]

Amateur Woodworker: Archive

Vol III, Issue 2. March/April 1999

Chinese Scroll Frame

This scroll frame was one of the more unusual challenges that we have been given

in the past couple of years. A relative had bought a Chinese scroll while on

vacation and needed a method of displaying it on the wall. However, the scroll is

about 20 feet long - too long to fit in a small apartment. As a result, we needed to

develop a method of allowing a section of the scroll to be viewed at a time, but

with the ability to easily (and the word "easy" was used several times) change the

view. The result was this Cherry scroll cabinet which has small dials underneath it

to allow the scroll to be moved on or rewound as required.

Trivet

A trivet is a quick and easy project that can be used either in the kitchen or as part

of a more formal setting in the dining room, depending on your needs. The project

can be easily built from start to finish in a weekend (indeed in a day if you use

fairly fast-setting glue). We used some left-over scraps of Cherry to build this

trivet, but you can use any hardwood - particularly as the wood does not come into

direct contact with the hot pots and pans.

Vol III, Issue 1. January/February 1999

Workshop Bench

This workbench plan uses 2 x 4s to produce a relatively cheap, and functional,

workbench that can be constructed in a day. Although the plan does not include a

vise, the inherent stability of this workbench means that you can easily add one if

so required. Under the workbench we have included very basic drawers, hidden

behind cupboard doors, that can be used to store all of your power - and other -

tools.

Chinese Abacus Lamp

The point of this project was to design a low-light lamp that would provide

interesting shadows through the use of two abaci (the plural of abacus?). However,

these particular abacuses have sentimental value to my aunt and, while she

certainly wanted to do something with them, she did not want them to be damaged.

The result was this Chinese-influenced lamp, which allows the abaci to be freely

removed.

Quilt Hanger

A quilt hanger is a very simple project. At its most basic, the hanger is essentially

http://www.am-wood.com/archive/archive.html (2 of 11) [11/3/2003 1:37:11 à«]

Amateur Woodworker: Archive

two pieces of thin wood that are screwed together, clamping the top of the quilt in

between them. This is our rendition of a seemingly simple project.

Vol II, Issue 8. November/December 1998

Bird Nesting Box

As winter descends upon us, it is time to skip ahead and begin considering the

spring (it's certainly one way of ignoring the darker evenings!) In particular, now

is the time to start building a bird nesting box so that when the spring does arrive,

your local birds have a nice new home. By putting the box out in the winter, any

human-related smells (such as the smell of the varnish) will have merged nicely

into the more expected aroma of nature by the time the birds come knocking on

the door.

Storage Shelving

Functional storage shelving is one of the most often request projects from you, our

readers. The need varies from somewhere to keep those bulk purchases in the

basement to simple shelving for in the workshop. Our resulting project should

accommodate either choice and leaves plenty of room for modification to suit your

own particular requirements. More importantly, the project is very cheap as it uses

standard 2-by-3's as the main framework. Although this is rough, construction-

grade lumber, once sanded down it provides a perfectly adequate surface for

painting or even varnishing.

Vol II, Issue 7. September/October 1998

CD Cabinet

There are two schools of thought when it comes to storing your CDs. The first

school is based on the idea that CDs are something that should be displayed while

the second school says that CDs should be hidden away - to be brought out only

when choosing the next musical choice. I'm a believer in the latter school and so I

created this CD cabinet. The underlying design idea was to make a mission-style

cabinet which can form part of the core furnishings in a living room.

Picture Frame

The idea behind this picture frame was twofold. The main goal was to build a

frame that did not detract from the photo held within it (in this case a landscape

shot). The second goal was to try and portray a sense of depth to the picture. The

first goal was easily attained by using solid hard maple to create a strong feel to

the frame and the second goal was attained by leaving space between the glass and

the photo.

http://www.am-wood.com/archive/archive.html (3 of 11) [11/3/2003 1:37:11 à«]

Amateur Woodworker: Archive

Vol II, Issue 6. July/August 1998

Mission-style lamp

The majority of lamps that are available on the market involve the use of a lathe.

However, turned lamps are not the only solution and, as this lamp proves, it is

entirely possible to build an attractive lamp without any special tools whatsoever.

This lamp is heavily influenced by the Mission-style, a style that is increasing in

popularity at present. The lamp is very easy to make and the project can be

completed in a weekend.

Ergonomic stool

Ergonomic stools provide the combined benefit of being both good for your back

and being a convenient spare due to the fact that you can fold them up when they

are not in use. The stool is surprisingly easy to construct: there are no complicated

joints to make and no special tools required. This stool is made out of 1 1/2" thick

dowel, which can be difficult to find. However, if you cannot find this thickness

you can get away with 1 1/4" wood.

Vol II, Issue 5. June 1998

Chest of Drawers

Building a chest of drawers is a surprisingly easy project and is well worth the

effort as it means that you can build a chest that is large enough to fit all of your

particulars in it. Typically, you can build this chest of drawers in a weekend,

although you should expect the project to take a little longer if you intend to paint

it.

Chisel Sharpening Jig

One of the hardest, and most frustrating, things that you have to do as a

woodworker is sharpen chisels. This seemingly simple task soon becomes one of

the dreaded jobs that you try to avoid for as long as possible. The problem is that

sharpening your chisels properly is difficult, and not sharpening them properly

affects the quality of your work dramatically. The sharpening fixture is a great

time (and money) saver while producing for the beginning turner a perfect cutting

edge every time.

Vol II, Issue 4. May 1998

Kitchen Garbage Can

Kitchen garbage containers are usually very ugly and the best approach is usually

to buy a small plastic container that will fit under the sink. However, after

http://www.am-wood.com/archive/archive.html (4 of 11) [11/3/2003 1:37:11 à«]

Amateur Woodworker: Archive

pondering this problem for a while, I came to the conclusion that there was

absolutely no reason why garbage cans cannot be made out of wood. The result

was this wooden garbage can. Having completed the project, I then passed it over

to my wife who painted and varnished it. Although the project looks complex, it

can easily be completed in one weekend and involves no special skills or joints.

Breakfast Bar

Breakfast bars and side shelves are usually rather bland and basic; essentially they

are little more than a plank of wood. However, Keith Antolik saw the opportunity

to build a far more interesting project that looks far nicer than a typical bar shelf.

The project was built out of white oak and all of the dimensions can be easily

changed to fit your specific needs.

Vol II, Issue 3. April 1998

Magazine Rack

Building a magazine rack is a relatively easy project that you can complete in a

weekend. It doesn't require much wood so you may even be able to make it out of

the odds and ends lying around in your workshop. Your family will also be happy

with the result as you can now tidy-up your woodworking magazines that are no

doubt strewn around the house! We used a relative dark wood for this project, but

you can easily use birch, or something similar, and stain to the desired color.

Puzzle Box

This box is based on an old Japanese style of concealing the mechanism that

allows the box to open. Rather than just having a simple sliding top, this box also

has a concealed locking mechanism that must be dealt with in order to open the

box. To open the box, the front strip of cocobolo must be slid to one side, thus

allowing the top to slide out freely. To make the box more interesting, three types

of wood were used: cherry (for the main panels); cocobolo (for the top and middle

strip); birch (for the small corner pieces).

Vol II, Issue 2. March 1998

Cookbook Holder

While the cookbook holder has grown in popularity, it has remained rather

simplistic, almost boring, in design. When we set about building our own version

of this useful tool, the main concern was to ensure that it was both practical and

http://www.am-wood.com/archive/archive.html (5 of 11) [11/3/2003 1:37:11 à«]

Amateur Woodworker: Archive

stylish. The result is a holder that owes far more to music stand design than to the

current selection of cookbook holders available in the stores. But although the

result looks rather nice, the construction is still very easy and the project can easily

be completed in a weekend.

Router Table

A router table is an invaluable tool. The problem, however, is that ready-built

router tables are usually relatively expensive and too narrow for many projects.

This router table provides a workable area of 15" (381 mm) which will allow you

far more flexibility than a shop-bought model. Further, the back support can be

removed from the table to allow for free-form routing, if so desired.

Vol II, Issue 1. February 1998

Knife Block

A knife block is a simple project that takes very little time to make. Furthermore,

by making this yourself, rather than using a shop bought version, you are safe in

the knowledge that all of your knifes will fit into it...at least you will be if you built

the block with this in mind! The knife block is made out of Red Oak, a hardy

wood that will withstand the rigors of the kitchen fairly well.

Chisel Cabinet

Chisels are one of the most valuable groups of tools you can own, and should be

treated with care if you want them to last well. With this in mind, we offer this

chisel cabinet as an ideal storage solution. The cabinet is designed to store both

normal chisels and carving chisels. In addition, the plan can very easily be adapted

to become a multi-purpose tool cabinet.

Vol I, Issue 9. December 1997

Desk Clock

Desk or mantle clocks make ideal Christmas presents, especially for the uncle who

already seems to have everything he could possibly need. The problem is that the

typical clock design is rather boring, being a rectangular block of wood with a

clock mechanism stuck on it. Of course, it doesn't have to be that way and so we

present this clock design not as a fait accompli, but rather as a starting point for

your own creativity.

http://www.am-wood.com/archive/archive.html (6 of 11) [11/3/2003 1:37:11 à«]

Amateur Woodworker: Archive

Zen Rock Garden

"Through Zen philosophy, one can experience the large in the small. And in a

grain of sand, glimpse the meaning of the world." For centuries, Japanese Zen

masters have practiced this philosophy by cultivating gardens of harmoniously-

arranged rocks and raked gravel. With this plan we have tried to make the project

slightly more ornate than the usual mass-produced version, while still adhering to

a Zen-like simplicity (we hope). Apologies in advance to any Zen traditionalists...

Vol I, Issue 8. November 1997

Bread Box

Bread boxes are very easy to make and so it is almost a crime to consider buying

one -- unless for some reason wood will not go in your kitchen. This particular

bread box is based on one of the more common designs and is therefore easier to

build than one with a roll-top lid.

Bird Table

This is the second type of bird table offered by Amateur Woodworker. The

advantage of this particular model is that you can easily put table scraps onto it,

rather than the relatively expensive bird seed needed for the other design. And let's

face it, the birds are happy to get anything in the winter...especially if you're a

good cook!

Vol I, Issue 7. October 1997

Bird Table

This month, Amateur Woodworker features the first of two styles of bird feeder

(the second will be published next month). This particular feeder is designed to

take bird seed, rather than the more typical left-over food scraps. The advantage of

this style is that it can be filled up infrequently as it can store several weeks worth

of food at a time. The bird feeder is made out of pine and is stained to suit its

locale.

Basic Entertainment Center

This entertainment center is a rather primitive affair, as it is an "open-plan" design

with no doors. The philosophy behind this decision was that by leaving the design

http://www.am-wood.com/archive/archive.html (7 of 11) [11/3/2003 1:37:11 à«]

Amateur Woodworker: Archive

open I would be less tempted to simply throw any old junk into center's hidden

recesses. This design also allowed me to employ a curved design, rather than the

more typical straight edges, and this reduced the unit's presence in the room -- as

the room is rather small, this was deemed to be very important.

Vol I, Issue 6. September 1997

Carved Owl

The owl is a departure from Amateur Woodworker's normal type of project in that

it involves carving rather than the more usual woodworking skills. However, it is

still in keeping with AW's philosophy of needing just a handful of tools. In fact, if

anything, this project requires less power tools than normal, although a couple of

carving chisels will certainly help things along. The carved owl is a variation on a

traditional Russian design and can be used as an ornament, or as a functional coat

hook.

Desk Organiser

Computers seem to create more paper than they save these days, as anyone with a

small computer desk can attest to. The battle against clutter is easily lost, making it

very difficult to find anything that you need quickly. With this goal in mind

(especially in my wife's mind) I finally built a desk organizer and designed it to

have small drawers for hiding the more junky items, such as floppy disks, staples

and so on. The organizer also had to accommodate the modem and a SyQuest

drive, hence the open shelves above and below the drawers.

Vol I, Issue 5. August 1997

Coat Rack

This coat rack is one of the simpler projects that we have featured in Amateur

Woodworker. It was designed to fit in a small hallway and had to accommodate

both coats and the usual paraphernalia such as gloves and hats (hence the shelf).

The reasoning behind the lemgth of the coat rack was to allow wet coats to rest

against the wooden slats, rather than the wall, as well as allowing for more coat

hooks to be fitted into the relatively small space.

Bathroom Unit

Bathroom under-sink units are, traditionally, rather dull, typically being very box-

http://www.am-wood.com/archive/archive.html (8 of 11) [11/3/2003 1:37:11 à«]

Amateur Woodworker: Archive

like in design. However, in small bathrooms, where space is of a premium, a box-

like shape takes up too much space. This curved under-sink unit was designed to

fit into a small bathroom and while it may not save much physical space, it

certainly provides the illusion of being much smaller than it actually is.

Furthermore, by building curved doors, the unit becomes a major feature in a small

room.

Vol I, Issue 4. July 1997

Artist's Easel

Earlier this year I was vaguely considering purchasing an artist's easel, but a very

cursory look in the local art shop soon put a stop to this idea: easels are expensive!

Quite why they cost so much is beyond me as they are a very simple construction

(let's face it, the average easel consists of three sticks for legs, with a couple of

horizontal pieces to hold the artwork up). So, rather than buying one, I decided

that it would be far more fun to design and build it.

Mah Jong Box

My parents-in-law have owned this Mah Jong set for several generations, but have

never had a safe place to keep it. Instead, the pieces have been stored in a

cardboard box that is in a rather decrepit state. Upon examination recently, it was

agreed that the cardboard could no longer be repaired using tape and so I set about

making this box. Of course, not many people want such a container, but it could

also be used for jewelry or (if the dimensions are expanded) for silverware, sewing

tackle or whatever. The options are seemingly endless. The box has five trays

inside it.

Vol I, Issue 3. June 1997

Adirondack Style Chairs

Adirondack chairs have become very popular in the past few years. The shape and

angle of these chairs is somewhere between a normal garden chair and a slovenly

deck chair. The result is a surprisingly comfortable chair that, unfortunately, costs

far too much. Fortunately, making an Adirondack chair is not difficult and can cost

as little as $20, depending upon the wood that you use.

Adirondack Style Rocking Chair

http://www.am-wood.com/archive/archive.html (9 of 11) [11/3/2003 1:37:11 à«]

Amateur Woodworker: Archive

For the slightly more adventurous, we have added this interesting variation on the

standard Adironadack style: a two person rocking chair.

Curved Bedside Cabinets

Most bedside cabinets are a rather dull design, being simply a box-like shape.

When these bedside cabinets were designed, we wanted to subtly change the shape

and feel of the cabinets, but without removing any of the functionality. In order to

change the shape slightly, it was decided to make the front of the cabinet curved,

rather than producing the more normal flat drawer fronts. Before anyone throws up

their hands in disgust, thinking that we used some sort of steamer to bend the

wood, don't worry...we cheated! No wood has been bent: instead, it has simply

been planed and sanded into this shape.

Vol I, Issue 2. May 1997

Shelving Unit

Shelving has always struck me as being a particularly boring thing to build. The

standard shelving unit has two sides, a back and a number of actual shelves in the

middle. Because of this, it was a project that I delayed for as long as I possibly

could, but finally the sheer mass of clutter in my home forced my hand...or was it

my wife's insistence that I clear up my "junk" somehow.

Storage Chest

This chest was designed to have a dual purpose: firstly (and most obviously) as a

storage unit and secondly as a coffee table in a small living room. The shape is

very basic, but is the most functional for storing toys and games in. In order to

improve the aesthetic appeal of the chest it was decided that dovetail joints would

be used to join the sides. Details of how to create easy dovetail joints has been

included in the Joints section.

Vol I, Issue 1. March/April 1997

Bedside Lamp

Are you looking for a bedside lamp that is different from the run-of-the-mill

department store examples? This lamp was constructed using only two power

tools: a drill and a jigsaw.

http://www.am-wood.com/archive/archive.html (10 of 11) [11/3/2003 1:37:11 à«]

Amateur Woodworker: Archive

Compact TV Cabinet

Although desirable, it is not always easy to add a television into a bedroom where

space is a premium, especially once room has been made for the necessities of life,

such as bedside cabinets, closets and a chest of drawers. This TV cabinet has been

designed to take up as little as 23 inches of wall space...

http://www.am-wood.com/archive/archive.html (11 of 11) [11/3/2003 1:37:12 à«]

Amateur Woodworker: TV Cabinet

Entertainment Center

With this project we are revisiting an

earlier theme: how to make a TV

(and its associated VCR, Cable box

and other paraphernalia) less

intrusive in a fairly small room.

While the popular approach is

typically to hide everything behind a

large entertainment center, we

remain unconvinced that this is the

best approach. Instead, we offer the

following TV solution that leaves the

television in full view while hiding

all of the other equipment. What

makes this a really clever solution is

the use of an infrared repeater device that allows the viewer to operate the cable

box and VCR with the doors closed.

Construction

Tools required: Router, sander, saw, drill

Wood required: (Cherry)

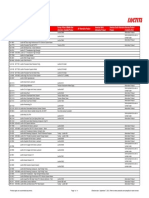

Description Qty Width Thickness Length

Side legs 2 2 3/4" 1 3/4" 14"

Back leg wide 1 2" 3/4" 14"

Back leg narrow 1 1 1/4" 3/4" 14"

Front legs 2 2 3/4" 3/4" 14"

Side frame (top and bottom) 4 1 1/2" 3/4" 9 3/4"

Front frame (top and bottom) 2 1 3/4" 3/4" 28 1/2"

Back frame (top and bottom) 4 1 1/2" 3/4" 28 1/4"

Side panels 2 10 1/2" 1/2" 9 3/4"

Back panels (plywood) 2 10 1/2" 1/2" 28 1/4"

http://www.am-wood.com/may99/tv.html (1 of 7) [11/3/2003 1:37:37 à«]

Amateur Woodworker: TV Cabinet

Inside supports 4 1" 3/4" 14 1/2"

Inside cross beam 2 1" 3/4" 28 3/4"

Shelf support strip (back) 2 3/4" 3/4" 28 1/2"

Shelf support strip (side) 2 3/4" 3/4" 9 3/4"

Top/Middle/Base (plywood) 1 48" 1/2" 96"

Top edging (sides) 2 1/2" 1/4" 12 1/2"

Top edging (front) 2 1/2" 1/4" 32"

Middle edging strip 1 1/2" 1/8" 28"

Doors 2 10" 1/2" 14" **

** See point 14 below, which explains how to get wood this wide.

1. Build side legs

The first step (and most complex) is cutting the two

side legs to the correct size. These legs are cut from a

block of cherry that is 2 3/4" x 1 3/4" in profile and

14" long. Firstly, nominate two adjoining sides to be

the inner sides (one will face towards the front while

the other will face the back corner of the unit). Then,

mark out the sloping cut on the side profile and cut

this using a circular saw (or preferably a table saw). When this is done, mark out

the second slope and also cut this.

The end result is a leg that is 2 3/4" x 1 3/4" at the base and 7/8" x 7/8" at the top

(see diagram). Repeat the above steps to make the second front leg, but ensure that

the second front leg is a mirror image of the first. Once these legs are cut to shape,

plane them (if necessary) to make sure they are even and then sand.

2. Build front legs

Next, cut the front legs to shape. These legs should match the profile of the side

legs as seen from the front (i.e. sloping in towards the unit at the top) but should

not have a side slope (hence why the wood is only 3/4" thick). Because of this,

there is only one cut needed for each leg and the result should be a leg that is 2

3/4" x 3/4" at the bottom and 7/8" x 3/4" at the top.

3. Build side panels

http://www.am-wood.com/may99/tv.html (2 of 7) [11/3/2003 1:37:37 à«]

Amateur Woodworker: TV Cabinet

Now that the four main legs are cut to shape it is time to

prepare the rest of the side panel components. Take the

four side frame pieces and rout a 1/2" wide groove (1/4"

deep) out of the narrow, long "top" of each one. This

groove will allow the framing pieces to slot over the top

and bottom of the side panels, thus forming one strong

unit (see diagram). Once this is done, glue the top and

bottom frame pieces to the side panel to form one main

unit.

Once the side panel is built we need to cut a bevel

along the side of the panel that will face forward. To

do this, decide if the panel will be on the right or left

side of the TV cabinet as you ar efacing the cabinet.

Presuming that this will be the right hand side panel,

cut a 45 degree bevel on the left hand side of the panel as shown in the diagram.

Note that the bevel means that the side of the panel that faces outwards is now

longer than the inner-facing panel. You have now completed one side panel.

Repeat the above steps to build the second (left) panel, being careful to cut the

bevel on the right side this time.

4. Combine side panels and legs

Now that both panels are cut to shape, it is

time to glue the legs to them. First attach the

rear leg to the non-bevelled side. To attach

the legs to the side panels use dowel joints

from the legs into the top and bottom frame

pieces (therefore, two dowel joints per leg).

Once the rear leg is attached, dowel and glue

the from leg into position. The front leg

should be attached along the bevelled side

and should therefore be at a 45 degree angle

to the side. Repeat for the second side so that

you now have two side panels, each with two

legs attached to it (see diagram). Note that teh

side panel should be attached flush with the

top of the legs. Therefore, the leg should protrude 1" below the bottom of the side

panel.

5. Build rear leg

http://www.am-wood.com/may99/tv.html (3 of 7) [11/3/2003 1:37:37 à«]

Amateur Woodworker: TV Cabinet

Now build the back leg. To do this, take the two pieces of

wood and glue/dowel the 1 1/4" wide piece onto the wider

piece as show in the diagram. The result is a rear leg that

protrudes an even amount in either direction.

6. Build back panels; attach to side panels

Next take the back frame pieces and rout out a groove that is 1/2" wide and 1/4"

deep in one 3/4" side of each piece. This groove will allow the back panel

plywood to slot into place, thus forming a complete panel (consisting of the top

and bottom cherry pieces and a main plywood panel. Once this is done, glue the

main panel into the top and bottom pieces and then attach the resulting rear panel

between the rear leg and one of the two side panels. To attach these pieces

together, use dowel joints into the top and bottom frame pieces from the rear and

back legs and glue. Repeat for the other back side. The result should be a frame

that is missing just the front component (where the doors will fit).

7. Build front frame; attach to complete TV stand frame

To finish the frame we need to attach the front frame pieces.

However, before we do that it is necessary to rout out a 1/4" deep,

1/4" wide groove from one edge of each piece. This will provide a

ledge for the door to rest against so it is important to decide which

piece will attach where and ensure that the groove is taken out of

the correct area of the wood (see diagram). Once these grooves

are cut, attach the top piece using dowel joints again. Then attach

the bottom piece. This should be attached 1" from the bottom of

the leg so that it matches the height of the other side panels. The

result is a complete frame.

8. Build base frame work

Now that the main frame of the TV cabinet has been built, it is time to consider the

inside. First we need to build the base of the unit. However before we can add the

plywood base we need to build a framework that will better support the base, and

stop it from warping over time. This frame consists of two front-to-back supports

(we define the "front" to be side with the doors) and a cross-member that connects

between these two supports.

The two supports should be cut to a length of 14 1/2" with a 45 degree miter in one

end of each support (this will be the back end). The support should be doweled and

glued onto the back of the front leg so that the top of the support is 1/2" lower than

the door frame. [In other words, the bottom of the support should be 1 1/4" from

http://www.am-wood.com/may99/tv.html (4 of 7) [11/3/2003 1:37:37 à«]

Amateur Woodworker: TV Cabinet

the bottom of the leg]. The back end of this support should be doweled into the

lower rear frame, again, 1/2" below the top of the cherry lower frame. Repeat for

the second front-to-back support.

Next, add the cross member support. This should be glued and screwed between

the two front-to-back supports, 12" from the front of the cabinet.

9. Cut base to shape and drop in.

Now that we have built the lower frame, we need to add the base plywood. The

first thing to do, of course, is to cut this plywood to shape so that it fits snuggly

into place. The best way to do this, is to turn the TV cabinet frame upside-down

onto the plywood. Then you can draw around the inside of the TV frame to get an

accurate shape for the inside. Once this is done, cut the plywood to shape. When

cutting, err on the side of caution. Remember: you can always cut more, but it's

really difficult to add the wood back if you cut too much! Once cut, drop the

plywood into the frame and make sure it offers a good tight fit. When you are

satisfied with the fit, copy the shape onto a second piece of plywood and cut out an

identical shape. This second piece will be the middle shelf. Finally, put the base

plywood back into the unit and glue in place.

10. Add middle support strip; add middle shelf.

Now that the base level is complete, we need to build an edging frame that will

hold the middle shelf in place. To do this, glue and screw the shelf support strips

around the inside of the TV unit so that the top of the support strip is at a height of

4 3/4" above the base shelf. Leave these to dry overnight and then slot the middle

shelf into place. Once the middle shelf is in place, add the small middle shelf

edging strip to the front edge of the plywood which is still viewable.

12. Build top framing.

To build the top framing, repeat step 8. The only difference is that this frame

should be flush with the top of the TV cabinet as its job is to support the top

plywood panel, which rests on top of the overall frame.

13. Cut top to shape and glue/dowel into place.

To cut the top plywood to shape, first turn the TV frame upside down on top of the

plywood sheet and draw around the outside of the frame. Then, add a border of 1"

all the way around this frame and then cut out the shape. To attach the top to the

frame use dowel joints into the frame and glue. Clamp overnight to ensure a good

seal.

http://www.am-wood.com/may99/tv.html (5 of 7) [11/3/2003 1:37:37 à«]

Amateur Woodworker: TV Cabinet

When the top is securely fastened, glue and nail (very fine brad nails) the edging

strip to the sides of the top, thus hiding the "layered" look of the plywood.

14. Make doors.

The doors are almost 14" wide (take an accurate measurement yourself to ensure a

good fit) and it is unlikely that you purchased wood that wide. As a result, before

constructing the doors you will need to dowel and glue to sheets of wood together

to gain the necessary width.

Before attaching the doors, cut a 1/4" deep, 1/4" wide groove in the top and bottom

of each one. The side that you cut these grooves into will become the inside of the

door panel. This groove should match up with the top and bottom band grooves,

thus allowing the doors to close snuggly.

To finish off the doors, attach the door strengthening

bar to each door. This is to help stop the doors (which

are quite thin) from warping too easily. This bar

should be glued onto the inside of each door panel at a

height of 6" from the bottom of the door. Further, this

panel also provides a stronger place to attach the door

pull into. Note that the door strengthening bars should

have mitered edges, rather than being cut straight at a 90 degree angle as you

would usual (see diagram).

To attach the doors to the unit, use offset hinges (see diagram). These

mean that you do not need to make insets for the hinges and, further,

will allow for the fact that the hinges must fit tightly against the front

legs.

15. Cut air vents out of back.

Because you will be putting the VCR, cable box and other electrical appliances

inside of the unit, it is a good idea to cut some air holes in the back panels of the

cabinet. To do this we used a 1/2" diameter drill bit and cut a line of holes in each

of the two back panels. Any size of air hole can be cut, but the smaller the hole,

the more you will need to cut.

16. Finishing

Finally, sand down the entire unit and finish with wax or oil. To add the infrared

http://www.am-wood.com/may99/tv.html (6 of 7) [11/3/2003 1:37:37 à«]

Amateur Woodworker: TV Cabinet

repeater mentioned in the introduction, drill a hole in the center of the top, front

frame piece and insert the infrared "eye." This can be purchased from certain

electronics stores, or from the Rockler catalog (see www.rockler.com).

http://www.am-wood.com/may99/tv.html (7 of 7) [11/3/2003 1:37:37 à«]

Additional Photos

http://www.am-wood.com/may99/tv2.html (1 of 2) [11/3/2003 1:38:02 à«]

Additional Photos

Close this window to return to main plan

http://www.am-wood.com/may99/tv2.html (2 of 2) [11/3/2003 1:38:02 à«]

Amateur Woodworker: Baby Changing Table

Baby Changing Table

Baby changing tables are a

wonderful - yet expensive - addition

to any nursery. With that in mind we

set about building a baby changing

table that would provide a strong

combination of practicality and

price. The resulting table has

subsequently been "battle-tested" for

the past month and has stood up to

the demands of both mother and

baby. Even better, when your baby (finally) outgrows the need for diapers, the

changing table can be used as a children's chest of drawers. Note that the baby

changing table does not have a rail around the top. Instead, it is designed to

accommodate one of the standard curved foam changing pads.

Construction

Tools required: router, drill, sander

Wood required: pine and plywood

Description Qty Width Thickness Length

Front frame

Small verticals 2 2 1/4" 3/4" 32"

Long verticals 2 2 1/4" 3/4" 35 1/2"

Top/Middle long

3 2 1/4" 3/4" 30 1/2"

horizontals

Base plank 1 2 1/4" 3/4" 47"

Top/Middle short

2 2 1/4" 3/4" 14"

horizontals

Rear Frame

Small verticals 2 2 1/4" 3/4" 32"

http://www.am-wood.com/july99/baby.html (1 of 7) [11/3/2003 1:38:49 à«]

Amateur Woodworker: Baby Changing Table

Long verticals 2 2 1/4" 3/4" 35 1/2"

Top long horizontals 1 2 1/4" 3/4" 30 1/2"

Base plank 1 2 1/4" 3/4" 47"

Top short horizontal 1 2 1/4" 3/4" 14"

Side panel (small)

Verticals 2 2 1/4" 3/4" 32"

Top/bottom 2 2 1/4" 3/4" 16 1/2"

Side panel (large)

Verticals 2 2 1/4" 3/4" 35 1/2"

Top/bottom 2 2 1/4" 3/4" 16 1/2"

Middle panel

1 16 1/2" 1/2" 4"

(plywood)

Tops

Large (plywood) 1 19 1/2" 1/2" 34 1/4"

Small (plywood) 1 19 1/2" 1/2" 18 1/2"

Edging (large top) 1 3/4" 1/8" 55"

Edging (small top) 1 3/4" 1/8" 60"

Molding (large top) 1 3/4" 3/4" 55"

Molding (small top) 1 3/4" 3/4" 60"

Base board

Front 1 3" 3/4" 51"

Side 2 3" 3/4" 19"

Large drawers

Sides 6 5 1/2" 3/4" 16 1/2"

Inner Front/back 6 5 1/2" 3/4" 26"

Front 3 9" 3/4" 30 1/2"

Knobs 6

Narrow drawers

Sides 4 10" 3/4" 16 1/2"

Inner Front/back 4 10" 3/4" 9 3/4"

Front 2 14" 3/4" 16 1/2"

http://www.am-wood.com/july99/baby.html (2 of 7) [11/3/2003 1:38:49 à«]

Amateur Woodworker: Baby Changing Table

Knobs 2

Back panels

Large

1 32" 1/8" 32"

(hardboard/plywood)

Small

1 16" 1/8" 35 1/2"

(hardboard/plywood)

1. Prepare front frame pieces (left side)

Firstly, cut lap joints that are 1 1/2" in from each end

into the two top pieces (long and short), the middle

drawer pieces (two long, one short) and the base plank.

Next, cut a slot out of the base plank 13" from the right

and 29 1/2" from the left (hence, 4 1/2" wide). Note

that when deciding which end is the right and left of

this plank, lie the plank flat on the ground with the cut

out lap joint part facing upwards (see diagram).

Now that all of the horizontal pieces are prepared, we need to

prepare the vertical planks. Firstly, take one of the two shorter

vertical pieces and nominate it as the left vertical. Cut out

grooves that are 3/8" deep and 1 1/2" in (matching the cut on

the horizontal pieces) at the following positions from the

bottom:

● Bottom to 2 1/4" high

● 10 3/4" to 13"

● 20 1/2" to 22 3/4"

● 29 3/4" to top

Next, take the second small vertical and nominate it as the middle-right vertical.

Make a mirror image of the above grooves in this piece, so that the horizontal

planks will slot in. The one difference is that the base to 2 1/4" high cut should be

made as a lap joint (i.e. all the way across the wood, rather than just 1 1/2" in) in

order to slot into the middle groove cut out of the base plank.

2. Prepare front frame pieces (left side)

Now take one of the two longer vertical planks and nominate it as the right

vertical. Cut out grooves that are 3/8" deep and 1 1/2" in (matching the cut on the

horizontal pieces) at the following positions from the bottom:

http://www.am-wood.com/july99/baby.html (3 of 7) [11/3/2003 1:38:49 à«]

Amateur Woodworker: Baby Changing Table

● Bottom to 2 1/4" high

● 17 1/2" to 19 3/4"

● 33 1/4" to top

Next, take the second long vertical and nominate it as the middle-left vertical.

Make a mirror image of the above grooves in this piece, so that the horizontal

planks will slot in. The one difference is that the base-to-2 1/4" high cut should be

made as a lap joint (i.e. all the way across the wood, rather than just 1 1/2" in) in

order to slot into the middle groove cut out of the base plank.

Finally, take the middle-right and taller middle-left planks and glue them together,

side by side. To make this joint use either dowel joints or biscuits. The result

should be a double width piece that has one side taller than the other. Not that

when looking at this piece from the front, it should look like one solid piece - the

grooves should be in the back, not the front.

3. Glue front frame together

Once the middle, double

plank has dried, it is time to

connect the rest of the front

together. Glue and screw the

pieces together, ensuring that

the finished frame is square.

To help build a solid frame,

clamp overnight to ensure a

strong bond.

4. Prepare back frame

The back frame is relatively simple to construct as it consists only of an outer

frame. Repeat step 2, but omit the horizontal planks that define the drawer spaces

(but include the inner-left and inner-right vertical planks that are glued together as

on the front). One prepared, glue the pieces together (as with the front). Again,

ensure that the frame is square.

5. Build left (small) side panel

http://www.am-wood.com/july99/baby.html (4 of 7) [11/3/2003 1:38:49 à«]

Amateur Woodworker: Baby Changing Table

Take the two vertical side pieces and cut lap joints into

them, and matching lap joints in the two small

horizontal pieces. By so doing, the four pieces should

fit together into a rectangular frame (see diagram).

Next, rout out a groove on the inner, back edge of all

four pieces. This groove should cut in 1/2" and be 1/2"

deep. By making this groove all the way around the

inside edge, the plywood sheet that forms the side

panel can rest in place. Once routed, glue and screw

the four side planks together - making sure the joints

are square - and then glue the plywood panel into place

in the center (which will help strengthen the unit.

6. Build right (larger) side frame

Repeat step 5 for the right hand panel. Remember that this panel is larger due to

the fact that the right side of the front frame is also taller.

7. Build main frame

Now that the two sides, front and back have been built, it is time to put them

together. Sandwich the left hand side panel between the front and back panels and

screw the three pieces together by driving screws through the front frame into the

side as well as from the back frame into the side panel. Then attach the right hand

panel to complete the frame. Make sure that the completed frame is square.

8. Add middle panel

Next, add the small middle panel, gluing and screwing it into place. This panel

should fill the small void at the point where the front/back steps up from the lower

height to the taller level. At this time you should also add a small strengthening bar

to the bottom middle of the frame, running from front to back. To add it, glue and

screw into place from the front and back.

9. Add tops

The final strengthening trick is adding to table tops. First add the larger, lower top.

This should overhang the front and left hand side by 1", over-hanging the back by

1/2". To attach this top, glue and nail - or screw - down into the frame.

Add the smaller top to the higher part of the table next. Again, the overhang

should be 1" to the front and both sides.

http://www.am-wood.com/july99/baby.html (5 of 7) [11/3/2003 1:38:49 à«]

Amateur Woodworker: Baby Changing Table

10. Add edging strip and molding to top

Add the edging strip to front and sides of both tops. Use glue and small finishing

nails to hold the strip into place against the plywood edge of the table top. Next,

add the small molding to the meeting point between the top and the main frame,

thus making the two look more like one unit.

11. Make base panel and attach to base.

To finish off the main unit we need to add a base board that will

serve as feet. This is one solid plank that runs the entire length of

the unit. Route a curve out of the top side to round it off (see

diagram). Add to from and sides - using a mitered cut at each end -

using screws and glue. The board should overlap 1" with the frame,

providing adequate bonding space.

12. Make drawers

Take the two side pieces, the back and the inner front piece. Cut a

groove in each one that is 1/4" from the bottom of each piece and is 1/4" wide.

This groove will allow the base to slot into the drawer frame. Once you have cut

the groove, glue and screw the sides to the back piece, slot the base into the groove

and then glue and crew the inner front board. Make sure that the unit is square.

The result is a box without a lid.

Attach a 16" drawer runner mechanism to each side of the drawer, and to the

corresponding "hole" in the main unit of the chest. Ensure that all drawer

mechanisms are attached at the same height, so that the drawers are

interchangeable in the unit. To attach the runners to the main frame, you may need

to add a strip of wood to the rear verticals.

Finally, you need to add the front of the drawer to the box unit. However, before

doing this, you need to shape the front of the drawer. The edge of this should be

rounded using the same router bit as you used for the edging around the bottom of

the main unit. Once you have routed all four sides of the drawer front, attach it to

the drawer unit by gluing and screwing from the inside of the drawer outwards.

13. Finishing

Finally, nail the two back panel pieces on to the back of the unit and sand the

entire unit thoroughly and paint.

http://www.am-wood.com/july99/baby.html (6 of 7) [11/3/2003 1:38:49 à«]

Amateur Woodworker: Baby Changing Table

http://www.am-wood.com/july99/baby.html (7 of 7) [11/3/2003 1:38:49 à«]

Amateur Woodworker: Paper Towel Holder

Paper towel holder

This is a quick and easy project for anyone

who is fed-up with plastic paper towel holders

which never seem to work as well as they

should. The project should take less than two

hours to complete from start to finish and is a

great addition to any kitchen or workshop.

Construction

Tools required: jigsaw, router

Wood required: Cherry (almost any hard wood will suffice)

Description Qty Width Thickness Length

Sides** 2 3" 3/4" 5 1/4"

Base 1 3" 3/4" 11 1/8"

Main rod dowel 1 1 1/4" 1 1/4" 11"

End dowels 2 5/16" 5/16" 1"

** Note that it is easier to treat this as one large 10 1/2" piece until stage 3 (see

below).

1. Prepare base

To make the paper towel unit look less blocky, we

need to round off the base of the paper towel holder.

The easiest way to do this is to use a router with a

concave curve bit and run it down the length of each

side (see diagram).

2. Cut mechanism groove into side pieces.

http://www.am-wood.com/july99/towel.html (1 of 2) [11/3/2003 1:39:21 à«]

Amateur Woodworker: Paper Towel Holder

The side pieces hold the key to the

paper towel mechanism. Each side

piece needs a groove added in it (as

shown in the diagram) that will allow

the main dowel rod to slot in (by

pushing straight back) and then drop

down into the final "locked"

position. To make this groove, use a

3/8" router bit, cutting the groove to

a depth of 1/4". There is no easy way

to make this slot (although a router table helps) and the key is to cut the groove

slowly, with patience, having first marked the path of the slot. When cutting the

slot in the second side piece, remember that this should be a mirror image of the

first, not a direct replication.

3. Cut curve in side pieces

Once the slots are cut, round off the top of each side into a curve (diameter 3")

with a jigsaw or a bandsaw. Once done, cut the single length of wood (10 1/2"

long) into two separate side pieces (if you did not do this earlier).

4. Attach sides to base

Attach the side pieces to the ends of the base unit using either a biscuit join or

dowels (thus hiding the joint)

5. Prepare Rod

Drill a hole 3/4" deep and 5/16" diameter in the center of each end of the main rod

dowel. The easiest way to find the center of this 1 1/4" diameter dowel is to cut out

a 1 1/4" by 1 1/4" square of paper and draw a line from each corner (thus forming

and "X"). Place this square of paper over the end of the dowel, and the center of

the X is the center of the dowel end. Once you have drilled the holes, glue the

small dowel ends in to them, so that the small dowels protrude 1/4". This dowel

until should now slot into the side grooves made earlier, completing the project.

6. Sand and polish

To finish the project, sand and varnish it.

http://www.am-wood.com/july99/towel.html (2 of 2) [11/3/2003 1:39:21 à«]

Additional Photos

Close this window to return to main plan

http://www.am-wood.com/july99/towel2.html [11/3/2003 1:39:33 à«]

Amateur Woodworker: Corner shelving

Corner shelves

This corner shelves project is a very

simple weekend project. The shelves are

made out of plywood with cheap pine

used as the edging to give the effect of a

thicker, more solid type of wood (as well

as to provide a useful lip to stop things

getting knocked off too easily). The

longest part of this construction by far is

the painting. As such, this is a project that absolutely anyone can take on.

Construction

Tools required: Drill, jigsaw, router

Wood required (per shelf):

Description Qty Width Thickness Length

Main base (plywood) 1 16 1/2" 1/2" 16 1/2"

Side edging 2 1" 3/4" 8 3/4"

Angled edging 1 1" 3/4" 14"

Underside supports 2 1 1/2" 3/4" 16"

Plug 2 1/2" 3/8" 1/2"

First cut the plywood into a square 16 1/2" by

16 1/2". Then, nominate two adjoining sides

to be the wall sides. Measure 8 1/2" away

from one wall side along one of the non-wall

sides and make a mark. Repeat for along the

second non-wall side. Then, draw a line

between the two marks. The result should be a 45 degree angle as shown in the

diagram. Cut along this line with the jigsaw (or circular saw) to provide the shape

of the shelf.

Next, take the two side edging pieces and rout a groove in the inside edge (i.e. the

http://www.am-wood.com/may99/shelves.html (1 of 2) [11/3/2003 1:40:03 à«]

Amateur Woodworker: Corner shelving

edge that will rest against the plywood) that is 3/8" deep, 1/2" wide and 1/4" from

the top side of the edging. This will allow the edging to slot into the plywood, thus

making the construction stronger. Once you have routed out this groove, cut the

two pieces to a length of 8 3/4" each. Note that the cut made at one end of each

piece should be at a 45 degree miter, thus lining up with the profile of the plywood

(see above diagram).

Next, rout out a groove in the angled edging piece (again is 3/8" deep, 1/2" wide

and 1/4" from the top side of the edging). Note that this piece is longer than it

actually needs to be.

Once all edging pieces have been routed, glue the two side pieces onto the

plywood. Then glue the angled edging piece on, ensuring that it pushes up against

the two side edging pieces. Use small brad nails to fasten the edging into place

securely.

Once the glue is dry, use a saw to cut the excess wood off of the angled edging

piece, thus completing the desired shape. Now, take the two small plugs of wood

and glue them into the groove ends that are showing (one at each end of the angled

edging piece). Again, once dry, trim off any excess wood.

Now cut out the two underside supports. The end

that will fit up tight against the side edging should be

cut down to 1/4" thick, tapering up rapidly (in either

a curve as shown or as a straight line) to the full

width of 1 1/2". Note that one side piece should be

16" long, while the other should be 15 1/4" (as it will fit butt-up against the first

underside piece. Once both pieces have been cut to shape, glue and nail them to

the underside of the plywood on the two sides that will touch the walls.

To fasten these shelves to the wall, drill small holes in the underside supports and

use screws to attach to the wall. You should use at least two screws per support

(one near each end).

Finish the shelf by heavily sanding it, removing any sharp edges and generally

rounding off the whole shelf. Then paint.

http://www.am-wood.com/may99/shelves.html (2 of 2) [11/3/2003 1:40:03 à«]

Amateur Woodworker: Chinese Scroll Frame

Scroll picture frame

This scroll frame was one of

the more unusual challenges

that I have been given in the

past couple of years. A

relative had picked up a

Chinese scroll while on

vacation and needed a

method of displaying it on

the wall. However, the

scroll is about 20 feet long - too long to fit in a small apartment - and so we needed

to develop a method of allowing a section of the scroll to be viewed at a time, but

with the ability to easily (and the word "easy" was stressed to me) change the

view. The result was this Cherry scroll cabinet which has small dials underneath it

to allow the scroll to be moved on or rewound as required.

Although not relevant to the actual making of the project, it is interesting to note

the origin of this scroll (which is a replica). The scroll is entitled "A city of

Cathay." It is a joint work painted by five court painters Ch'en Mei, Sun Hu, Chin

K'un, Tai Hung and Ch'en Chih-tao during the first year of Ch'ien-lung reign (1736-

1795) in the Ch'ing dynasty.

Construction

Tools required: saw, sander, drill, jigsaw (or preferably a bandsaw)

Wood required: (Cherry)

Description Qty Width Thickness Length

Rear sides 2 3" 1/2" 13 1/2"

Rear top and bottom 2 3" 1/2" 30"

Front-facing sides 2 3" 1/2" 13 1/2"

Front-facing top/bottom 2 2 1/4" 1/2" 30"

Dial knob 2 1 1/2" 1 1/2" 1/2"

Dial dowel 2 7/8" 7/8" 1/2"

http://www.am-wood.com/march99/scroll.html (1 of 5) [11/3/2003 1:40:36 à«]

Amateur Woodworker: Chinese Scroll Frame

Joining dowel 2 3/16" 3/16" 2"

Collar 2 1" 1" 1/2"

Scroll dowel 2 1/2" 1/2" 12"

Plywood disc 2 2 1/2" 1/8" 2 1/2"

Top scroll dowel 2 3/16" 3/16" 1 1/4"

Glass restraints (side) 2 1/4" 1/4" 9"

Glass restraints

2 1/4" 1/4" 18"

(top/bottom)

Back restraints (side) 2 1/4" 1/4" 9"

Back restraints

2 1/4" 1/4" 18"

(top/bottom)

Back wall (plywood) 1 12 1/2" 1/8" 28 7/8"

The first step towards building the scroll frame is to

build the rear frame. Cut the four rear pieces to size,

with a 45 degree miter at each end of each piece. Then

glue the sides, top and bottom pieces together to from

a basic frame that is 3" deep (see diagram). Make sure

that this frame is square when gluing and subsequently

clamping.

Next, cut out the four pieces that make up the

front-facing frame. The two side pieces

should be cut at an angle of 55 degrees while

the two top/bottom pieces should have an

angle of 35 degrees (thus the combination of

putting a side piece together with a

top/bottom piece would result in 35 + 55 = 90 degrees). The reason for the odd

angle, rather than the more usual 45 degree cut is due to the disparity in wood

width between the sides and top/bottom pieces (see diagram).

Next, cut a 45 degree bevel along both of the front facing sides (see

diagram for side profile). This is done to avoid the problem of

making a frame that is too square and "boxy." The bevel is cut into both the inside

edge and the outside edge (obviously on the side that will be the up-facing side)

and will later be sanded down to round out the project.

Once all the pieces are cut to shape, glue the front pieces onto the underlying

frame (and to each other). To attach the front pieces to the underlying frame use

http://www.am-wood.com/march99/scroll.html (2 of 5) [11/3/2003 1:40:36 à«]

Amateur Woodworker: Chinese Scroll Frame

small brad nails (sink these nails just below the surface and use filler to tidy up the

small holes). Ensure that the front pieces are tightly pressed together (and square)

before nailing into place. Once the glue is dry, sand the unit heavily to produce a

rounded feel to the beveled edges. The main unit is now complete and we can now

begin to concentrate on the scroll mechanism

Before we work on the actual scroll

mechanism, nominate which end of the main

frame is the bottom. Then mark positions for

holes in the bottom side of the frame. These

holes should be 3/16" diameter, and should be

1 1/2" from the side and 1 1/2" from the top

of the inside (see diagram). Drill these holes all the way through. These bottom

holes will be used to connect the underneath dials to the internal scroll mechanism.

Then, make the same marks on the inside of the top frame (i.e. 1 1/2" from the side

and 1 1/2" from the back) and drill a hole 1/4" deep. Important note: this hole does

not go all the way through. The top of the internal scroll mechanism will sit in this

hole.

To build the scroll mechanism, first cut out two

circular pieces of cherry that are 1 1/2" diameter

and 1/2" thick. These will be the small dial knobs

that sit underneath the scroll frame. Drill a hole

1/4" deep and 3/16" diameter into the center of one

side of these knobs. This will accommodate the

small joining dowel that attaches the dial knob to

the main internal mechanism. Next, cut two pieces

of dial dowel 7/8" diameter and 1/2" long and drill a hole 3/16" diameter through

the center of each one. These small dowels will sit between the dial pieces and the

main frame (see diagram for more information).

Now that we have prepared all of the components that make up the dial knob,

build the complete construction by gluing the dowel and dial knob pieces together,

with the 3/16" diameter (2" long) dowel through the middle of it. Repeat for the

second dial unit.

Once the dial knob is complete, it is time to

work on the internal part of the scroll

mechanism. First, take the 1/2" diameter

scroll dowel (12" long) and drill a 3/16"

diameter hole that is 3/4" deep in each end.

This may seem a little tricky to begin with but

is actually very easy. It is important to take the time to make sure that you are

http://www.am-wood.com/march99/scroll.html (3 of 5) [11/3/2003 1:40:36 à«]

Amateur Woodworker: Chinese Scroll Frame

drilling the hole in the center of the dowel, however. To make sure that you drill to

the correct depth, measure along the drill bit to the correct distance and then wrap

some tape tightly around the drill bit just above this point. Once the tape reaches

the surface of the wood, you will know that you have drilled deep enough.

Glue a 3/16" diameter, 1 1/4" long dowel into one end of each scroll dowel. This

should result in 1/2" sticking out. This will be the top end of the scroll dowel. The

small 3/16" dowel protruding from the top of the scroll dowel will slot into the

small hole made in the inner frame previously (thus holding the top of the scroll

dowel in situ). Lightly sand this small dowel to ensure that it will not stick unduly

when placed in the hole.

Cut a small wooden collar out of some 1/2" thick cherry stock. The collar should

be 1" diameter and should have a hole in the center of it that accommodates the

scroll collar (1/2" diameter). Once the collar is complete, cut a disc of plywood

(1/8" stock) that is 2 1/2" diameter. Again, drill a hole that is 1/2" diameter in the

center of it to accommodate the scroll dowel. Note that it is often easier to drill the

hole in the plywood (and the collar) first, before then cutting the collar/disc to the

correct size.

Now prepare the scroll by stapling and gluing one end of the scroll to each of the

scroll dowels. The best glue to use for this is an almond paste or other paper glue.

While wood glue will work adequately, a paper-specific glue will give better

results.

At this point, finish the dial unit and main frame by either waxing or varnishing.

We chose to use a rub-on varnish which gives a nice rich finish (and requires little

maintenance moving forward), but whatever type of finish you want is perfectly

acceptable. It is important to apply the finish now, before putting the mechanism

together in order to ensure that the finish does not glue up the mechanism.

Once the finish is dry, place the glass into the

frame and add in the glass restraining pieces. To

stop the glass from rattling we recommend that

you apply a thin sliver of felt between the restraint

and the glass. This allows you to push down more

on the glass, giving a tighter fit. To attach the

restraints, screw through the restraints into the side

walls of the frame. Position the restraints in the center of each frame side.

Now put the scroll components together, as shown in the diagram above. Note that

the dowel that protrudes from the dial unit, though the main frame and into the

scroll dowel should not be glued into this scroll dowel. Instead, it should be attach

http://www.am-wood.com/march99/scroll.html (4 of 5) [11/3/2003 1:40:36 à«]

Amateur Woodworker: Chinese Scroll Frame

via a screw that goes through the collar, into - and through - the scroll dowel and

into the dial dowel. Note that to ensure that the wood does not split when attaching

this screw, drill a small (1/16" diameter) hole through the collar and scroll dowel.

Once the mechanism has been installed, and the scroll moves freely when the dial

knobs are rotated, it is time to add the back to the frame. To do this, we must first

add in the back wall restraints. These are attached via screws (as with the glass

restraints). Do not be tempted to use nails as if you do so, you will not be able to

replace the glass if it breaks. The back wall restraints should be positioned in the

center of each side 1/4" from the back (thus leaving room for the back wall to slot

in without overlapping the sides).

Finally, add in the back piece of plywood and attach it by nailing small brad nails

part way into the side walls, thus loosely holding the wall in place (but still

allowing removal of the nails and back wall if you need to get inside the frame

again.

http://www.am-wood.com/march99/scroll.html (5 of 5) [11/3/2003 1:40:36 à«]

Additional Photos

Close this window to return to main plan

http://www.am-wood.com/march99/scroll2.html [11/3/2003 1:40:54 à«]

Amateur Woodworker: Trivet

Trivet

A trivet is a quick and easy project that can be used

either in the kitchen or as part of a more formal

setting in the dining room, depending on your

needs. The project can be easily built from start to

finish in a weekend (indeed in a day if you use

fairly fast-setting glue). We used some left-over

scraps of Cherry to build this trivet, but you can

use any hardwood - particularly as the wood does

not come into direct contact with the hot pots and pans.

Construction

Tools required: router, sander

Wood required: (Cherry)

Description Qty Width Thickness Length

Sides 4 5/8" 3/8" 5 3/4"

Middle strips 3 5/8" 3/8" 5 3/4"

Edging strip 4 1/8" 3/8" 5 3/4"

Tiles 3/8" 1/4" 3/8"

The first step in this project is to prepare the four

side pieces. The easiest method of joining these

sides together is to use lap joints, whereby one

piece of wood sits on top of the other - overlapping

it (see diagram). The lap joint should cut into the

wood to a depth of 3/16" (half of the wood's thickness) and should cut back along

the length 5/8" (the result, once both ends have been cut should be a "clean" 4 1/2"

between each joint).

http://www.am-wood.com/march99/trivet.html (1 of 2) [11/3/2003 1:41:26 à«]

Amateur Woodworker: Trivet

Once you have cut all of the lap joints correctly on

the four sides, place the four pieces roughly in

position. Choose the two (opposite) sides that sit

over the top of the other two sides; these will be the

sides that join into the middle strips. Mark and cut

three slots that are 5/8" wide and 3/8" deep in the

lower half of these two sides (see diagram). These

three slots should be evenly spaced along the side (i.e. approximately 5/8" apart).

Once you have prepared the sides, join them together with glue and a small screw

(from the underside).

Now prepare the three central strips by cutting a

lap joint in each end of them (again, 3/16" deep

and 5/8" long). Then rout out a groove 3/8" wide

and 3/16" deep along the upper side (the side that

had the lap joint wood removed from it --see

diagram). Note: the depth of this groove depends

upon the thickness of the small tile squares: the

tile should protrude above the height of the wood

by at least 1/16". This groove should be positioned in the center of the piece

(therefore leaving 1/8" on either side). Once this is done, glue and screw (again,

from the underside) the three middle strips into the main unit, thus forming the

completed shape.

Next add the small edging strip to the outside edge of all four sides with glue and

clamp until dry. The purpose of this edging strip is to hide the unsightly lap joint

ends. Once the edging strip is firmly glued in place, sand the entire unit and then

wax or oil, depending on your preference.

Now glue the small tile squares into the grooves, ensuring that you evenly space

them. We recommend a fast setting epoxy-type glue for this task (make sure that it

is heat resistant!). Once dry, fill the gaps between the tiles with tile grout.

Finally, apply thin strips of felt to the underside of the trivet. This will have the

double benefit of firstly hiding the evidence of the small screws and secondly

ensuring that the trivet does not scratch your dining room table.

http://www.am-wood.com/march99/trivet.html (2 of 2) [11/3/2003 1:41:26 à«]

Additional Photos

Close this window to return to main plan

http://www.am-wood.com/march99/trivet2.html [11/3/2003 1:41:38 à«]

Amateur Woodworker: Workbench

Workbench

This workbench plan uses 2 x 4s to

produce a relatively cheap, and

functional, workbench that can be

constructed in a day. Although the plan

does not include a vise, the inherent

stability of this workbench means that

you can easily add one if so required.

Under the workbench we have included

very basic drawers, hidden behind

cupboard doors, that can be used to store

all of your power - and other - tools.

Construction

Tools required: drill, sander, router, saw

Wood required:

Description Qty Width Thickness Length

Legs 4 3 1/2" 1 1/2" 28 1/2"

Side panels (plywood) 2 24" 1/2" 25"

Cross member

4 3 1/2" 1 1/2" 27 1/4"

supports

Central supports 4 2 1/2" 1 1/2" 28 1/2"

Central plywood

4 21" 1/2" 28 1/2"

dividers

Main workbench

2 3 1/2" 1 1/2" 92"

support

Base supports 2 2 1/2" 1 1/2" 53"

Workbench surface

1 27 1/4" 1/2" 92"

(plywood)

Back panel

1 28 1/2" 1/4" 56"

(hardboard)

http://www.am-wood.com/jan99/bench.html (1 of 4) [11/3/2003 1:42:16 à«]

Amateur Woodworker: Workbench

Drawers:

Sides 16 4" 3/4" 21 1/2"

Front/back 16 4" 3/4" 15 3/4"

Base (plywood) 8 15 1/2" 1/2" 21 1/2"

Doors:

Top and bottom 6 1 1/2" 3/4" 18 1/2"

Sides 6 1 1/2" 3/4" 23"

Door panel (plywood) 3 17" 1/2" 21 1/2"

Door trim 1 1 1/2" 1/2" 56"

Begin the project by building the leg structures: take

two legs and rest them on a flat surface (wide side

down), parallel to each other and 17" apart. Then, take

one of the plywood side panels and glue and screw it

to the two legs, flush with the bottom of the leg (and

therefore 3 1/2" of leg should protrude above the top of

the plywood). Repeat for the other leg.

Next, take one of the cross member supports and cut out a niche 1 3/4" deep by 1

1/2" long out of each end (see diagram). The purpose of this niche is that it will

form half of a lap joint with the main bench support (see later). Once you have cut

the niche out of both ends of the cross member, glue and screw the cross member

to the top of the side panel construction made above. This cross member should

attach to the two legs at the point where the plywood left off, and should jut out 1

1/8" either side. Repeat for the second side panel.

Now take the four central supports and cut out a

niche 1 1/2" wide by 3 1/2" long out of the bottom of

each one. Rout a groove that is 1/2" deep and 1"

wide out of the two wide sides of each support on the

non-niched sides (see diagram). This groove is cut to

accommodate the plywood central panels so that they

sit flush with the supports.

Once the four central supports have been cut and routed, glue and screw the center

plywood dividers into place. One plywood divider should attach to either side of

the central support, thus producing a hollow wall effect.

Now that the walls of the under-unit are complete, add the drawer runners. There

are three columns of drawers: the left and right columns should have three drawers

http://www.am-wood.com/jan99/bench.html (2 of 4) [11/3/2003 1:42:16 à«]

Amateur Woodworker: Workbench

in them, while the central column has only two (to accommodate bigger power

tools). Attach drawer runners at a height of 3 1/2", 11" and 18 1/2" from the

bottom of the unit for the left and right two, and at a height of 3 1/2" and 14" for

the central column.

Once the center supports are complete, take the main workbench supports and cut

out a niche that is 1 1/2" wide, 1 3/4" high and 18" from either end, from the

bottom half of the supports (see diagram). This niche will allow the main support

to slot into the top of the two side pieces constructed above. Also, cut out a niche 1

1/2" wide and 1 3/4" deep from the top of each end (again, see diagram). These

end niches form half of a lap joint, the other half being made by the remaining two

central supports.

Cut out a niche 1 1/2" wide and 1 3/4" deep from the end of each remaining two

central supports, thus allowing these supports to slot into main workbench

supports when we put everything together.

Everything is now ready and we can begin to

build the main workbench structure. Start by

placing the two base supports on the floor,

parallel to each other and 17" apart. Then,

screw one of the side panels to one end of

these supports, and the other side panel to the

other end.

Next, screw and glue the two central panels into place, equidistant from each end

(17 2/3" from each side panel). To attach these, screw in from the front and back

of the base support. You should now have four panels sitting perpendicular to the

base. Add the two main workbench supports to the top of the construction, gluing

and screwing into all for panels. Make sure that all of the panels remain square

(i.e. they do not lean to one side or another).

Now add the two remaining central supports, one to each end of the main

workbench supports, to join the ends of the workbench together. You now have

the basic framework of the workbench complete. Glue and screw the main

workbench surface to the top of the construction. This will help to make the unit

more sturdy.

Finally, nail the hardboard panel to the back of the unit to seal off the drawers

from sawdust. This is an optional stage (particularly if the unit is going to be used

against a wall as we would advise) but it should cut down on sawdust "leakage."

Building the drawers

http://www.am-wood.com/jan99/bench.html (3 of 4) [11/3/2003 1:42:16 à«]

Amateur Woodworker: Workbench

The main bench frame is complete, and it is time to

build the eight drawers. The level of quality that you

throw at this issue is entirely up to you. We chose to

make very simple drawers that were screwed together -

no dovetailing or other nice joints were used. This was

acceptable (to us at least) because firstly this is a

workbench and secondly, the drawers will be hidden behind cupboard doors.

Take the side, front and back pieces and glue/screw them together, ensuring that

the frame is square. Then, glue and screw the plywood base to the underside. Once

dry, attach the drawer runners. The drawers should now slot into the spaces

allocated for them.

Building the doors

The doors are made from a pine frame and a plywood center.

First, cut the side, top and bottom pieces of pine to the

correct sizes. Each end of these pieces should be cut to a 45

degree angle to provide the correct joint (i.e. a 90 degree

angle). Next, cut the outside edge (outer facing) of the side

frame pieces to a miter of 45 degrees (see diagram). This is important firstly

because it makes the doors look less heavy, and secondly, to allow the second door

to open without pushing into door three.

Once you have mitered the two sides, rout out a groove on the inside, rear facing

edge. This groove should be 1/2" deep and 3/4" wide and is made to accommodate

the plywood panel. This groove should be cut out of both the two sides and the top

and bottom pieces. Once this is done, glue the four frame pieces together. At the

same time, add the plywood panel, gluing it into place (this will help to ensure that

the door is square).

Once the panel is dry, sand the door down to round off the miter to a smooth

curve. Then attach to the main unit with hinges. The door should be attached 1/2"

from the base (this leaving 1 1/2" above the door. Once all three doors have been

attached, glue and screw the final door trim piece into the center supports above

the doors (thus filling the gap between the workbench and the top of the doors.

Also at this time, add door knobs to the three doors.

http://www.am-wood.com/jan99/bench.html (4 of 4) [11/3/2003 1:42:16 à«]

Additional Photos

http://www.am-wood.com/jan99/bench2.html (1 of 2) [11/3/2003 1:42:41 à«]

Additional Photos

Close this window to return to main plan

http://www.am-wood.com/jan99/bench2.html (2 of 2) [11/3/2003 1:42:41 à«]

Amateur Woodworker: Chinese-style abacus lamp

Abacus Lamp