Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Petersen 2016

Uploaded by

Winda HaeriyokoCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Petersen 2016

Uploaded by

Winda HaeriyokoCopyright:

Available Formats

Review Article

Mild Cognitive

Address correspondence to

Dr Ronald C. Petersen, Mayo

Clinic, Department of

Neurology, 200 1st St SW,

Rochester, MN 55905-0001,

peter8@mayo.edu.

Relationship Disclosure:

Impairment

Dr Petersen serves on the Ronald C. Petersen, PhD, MD

board of directors for the

Alzheimer’s Association and

receives personal compensation

for serving as chair of the ABSTRACT

data monitoring committees

for Janssen Alzheimer Purpose of Review: As individuals age, the quality of cognitive function becomes

Immunotherapy and Pfizer an increasingly important topic. The concept of mild cognitive impairment (MCI) has

Inc. Dr Petersen receives evolved over the past 2 decades to represent a state of cognitive function between

personal compensation as a

consultant for Biogen, Eli Lilly that seen in normal aging and dementia. As such, it is important for health care

and Company, the Federal providers to be aware of the condition and place it in the appropriate clinical context.

Trade Commission, Genentech, Recent Findings: Numerous international population-based studies have been con-

Inc, Hoffmann la Roche, Inc,

and Merck & Company, Inc. ducted to document the frequency of MCI, estimating its prevalence to be between

Dr Petersen receives grant and 15% and 20% in persons 60 years and older, making it a common condition en-

funding support from the Mayo countered by clinicians. The annual rate in which MCI progresses to dementia varies

Foundation for Education and

Research, the National Institute between 8% and 15% per year, implying that it is an important condition to identify

on Aging, and the Patient and treat. In those MCI cases destined to develop Alzheimer disease, biomarkers are

Centered Outcomes Research emerging to help identify etiology and predict progression. However, not all MCI is due

Institute (PAT 206548).

Dr Petersen receives royalties to Alzheimer disease, and identifying subtypes is important for possible treatment and

from Oxford University Press. counseling. If treatable causes are identified, the person with MCI might improve.

Unlabeled Use of Summary: MCI is an important clinical entity to identify, and while uncertainties per-

Products/Investigational

Use Disclosure:

sist, clinicians need to be aware of its diagnostic features to enable them to counsel

Dr Petersen discusses the patients. MCI remains an active area of research as numerous randomized controlled

unlabeled/investigational trials are being conducted to develop effective treatments.

clinical trial results for mild

cognitive impairment.

* 2016 American Academy Continuum (Minneap Minn) 2016;22(2):404–418.

of Neurology.

INTRODUCTION of detecting very early clinical features

Identifying pending cognitive impair- of incipient disease.

ment at an early stage has become an Central to this diagnostic scheme

increasingly important challenge to is the clinical construct of MCI.2,3 MCI

physicians. Decades ago, it was satis- is generally regarded as the border-

factory to distinguish dementia from land between the cognitive changes

typical cognitive aging, but in recent of aging and very early dementia, but

years, the desire to make a more fine- while conceptually reasonable, the con-

grained decision on incipient disease struct poses difficulties in clinical prac-

has become apparent. In evaluating tice (Case 2-1A).4

persons for suspected Alzheimer dis-

ease (AD), the clinical spectrum from HISTORICAL ASPECTS OF THE

dementia has extended back to mild CONCEPT OF MILD COGNITIVE

cognitive impairment (MCI) and ulti- IMPAIRMENT

mately to preclinical AD, at which point Historically, the term MCI has been in

people are cognitively normal but har- the literature for almost 4 decades,

bor the underlying biological features with the initial use coming from in-

of AD.1 This puts the clinician in the vestigators at New York University

challenging but opportunistic position who referred to Stage 3 on the Global

404 www.ContinuumJournal.com April 2016

Copyright © American Academy of Neurology. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

KEY POINT

Case 2-1A h The Key Symposium

criteria for mild

A 66-year-old retired high school teacher presented for symptoms of

cognitive impairment

increasing forgetfulness, which he had begun to experience in the past 1

accomplished two

to 2 years. His other cognitive functions, including language, attention,

goals: (1) to broaden the

executive function, problem solving, and visuospatial skills, were all intact.

classification scheme

He continued to drive without difficulty and handled the financial matters

beyond memory, and

for his family without a problem. His wife had noted a slight increase in

(2) to recognize that mild

forgetfulness, but this had not been of concern to her. The patient noted that

cognitive impairment

he had been taking more time to remember previously well-remembered

could result from a

events such as appointments with his doctor, scheduled meetings with friends,

variety of etiologies

and planned visits with the children. He was not particularly disturbed by

and not just

these symptoms, and he had not made any major social mistakes. His

Alzheimer disease.

behavior was otherwise intact, and his mood was stable. He generally slept

well and did not admit to any features of dream enactment behavior. He was

concerned, however, because his mother had developed dementia later in

life and died of what was probably Alzheimer disease at age 81, and the

patient wanted to be assessed for the disease.

Comment. This scenario represents a common presentation to clinicians

with an aging patient population. This patient is more forgetful than he

formerly was and is worried about the possibility of a problem beyond

aging. This patient appears to have had progressive memory difficulties in

recent months to years. It did not appear that he had other extant medical

comorbidities that were influencing his condition. Mental status testing is

indicated and may provide further useful information, as is discussed in the

continuation of this case later in the article.

Deterioration Scale as being MCI.5 In incipient AD nor did all patients have

1999, a group at the Mayo Clinic de- just a memory impairment. To address

scribed subjects in their community this situation, the Key Symposium was

aging study who had a memory con- held in Stockholm, Sweden, in 2003,

cern beyond what was expected for and criteria of a more broad scope were

age and who demonstrated a slight published in 2004.2,7 These criteria ac-

memory impairment yet did not meet complished two goals: (1) to broaden

criteria for dementia.6 The research the classification scheme beyond mem-

criteria used to characterize these sub- ory, and (2) to recognize that MCI could

jects were described, and the clinical result from a variety of etiologies and

outcomes were noted. not just AD. These criteria are outlined

in Figure 2-1,8 demonstrating the syn-

MULTIPLE TERMINOLOGIES dromic phenotypes and how they can

Over the years, several sets of termi- be paired with possible etiologies

nology for MCI and related conditions to assist the clinician in diagnosis. The

have evolved, many referring to similar Key Symposium characterization of

constructs in the general MCI range. MCI led to the distinction between the

The Mayo Clinic criteria previously noted amnestic form of MCI and the non-

focused on a memory disturbance and amnestic form of MCI, since these clin-

were developed to elucidate the earliest ical syndromes appeared to be aligned

symptomatic stages of AD. However, with etiologies in a differential fash-

it soon became apparent that not all ion and may have variable outcomes.

intermittent cognitive states represented Traditionally, amnestic MCI is the

Continuum (Minneap Minn) 2016;22(2):404–418 www.ContinuumJournal.com 405

Copyright © American Academy of Neurology. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

Mild Cognitive Impairment

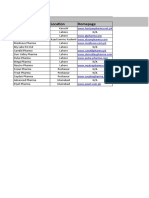

FIGURE 2-1 Key Symposium criteria. First Key Symposium criteria demonstrating the syndromic phenotypes

and how they can be paired with possible etiologies to assist the clinician in making a diagnosis.

AD = Alzheimer disease; DLB = dementia with Lewy bodies; FTD = frontotemporal dementia;

MCI = mild cognitive impairment; VCI = vascular cognitive impairment.

Modified with permission from Petersen RC, Continuum (Minneap Minn).8 journals.lww.com/continuum/Fulltext/2004/02000/

MILD_COGNITIVE_IMPAIRMENT.3.aspx. B 2004, American Academy of Neurology.

KEY POINTS typical prodromal stage of dementia due posium criteria while making some of

h Traditionally, amnestic to AD, but other phenotypes can also the diagnostic features more explicit.

mild cognitive impairment lead to this type of dementia, such as These criteria also added biomarkers

is the typical prodromal

logopenic aphasia, posterior cortical at- for underlying AD pathophysiology in

stage of dementia due to

rophy (also known as the visual variant), an attempt to refine the underlying

Alzheimer disease, but

other phenotypes can

or a frontal lobeYdysexecutive presenta- etiology and, hence, predict outcome.

also lead to this type of tion of AD.9 The essential feature of this These criteria did not differentiate be-

dementia, such as portrayal is that not all MCI is early AD. tween amnestic and nonamnestic MCI.

logopenic aphasia, The Key Symposium criteria pre- At approximately the same time, the

posterior cortical atrophy vailed in the field and influenced the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual

(also known as the visual development of several randomized of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition

variant), or a frontal controlled trials for possible interven- (DSM-5) was being developed.17 For

lobeYdysexecutive tion.10Y14 In 2011, the National Insti- the general category of neurocogni-

presentation of tute on Aging (NIA) and the Alzheimer’s tive disorders, the criteria now include

Alzheimer disease. Association convened workgroups to a predementia phase called mild

h Not all mild cognitive develop criteria for the entire AD spec- neurocognitive disorder. Once again,

impairment is early trum.1,9,15,16 The criteria for MCI due the construct is very similar to the

Alzheimer disease. to AD essentially adopted the Key Sym- Key Symposium criteria for MCI and

406 www.ContinuumJournal.com April 2016

Copyright © American Academy of Neurology. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

KEY POINTS

suggests that, in addition to the syn- the current sets of criteria, regardless h The criteria for mild

dromic classification, certain features of the terminologies, emanate from cognitive impairment due

would allow the subclassification of the Key Symposium criteria for MCI, to Alzheimer disease

the clinical presentation into patho- and most recent approaches embellish developed by the

logic etiologies. The category of mild these criteria with pathophysiologic National Institute on

neurocognitive disorder due to AD is biomarkers to lend specificity to the Aging and the Alzheimer’s

very similar to the classification of underlying diagnoses. The entire field Association essentially

MCI due to AD formulated by the NIA/ of aging and dementia is moving in adopted the Key

Alzheimer’s Association workgroups.17 this direction, and these criteria are Symposium criteria while

Finally, over the course of several likely to be important going forward. making some of the

diagnostic features more

years, the construct of prodromal AD

PREVALENCE explicit. These criteria

evolved.18Y20 This clinical condition

also added biomarkers

grew from the accumulating literature In the past decade, there have been for underlying Alzheimer

that had developed regarding the ob- numerous epidemiologic studies con- disease pathophysiology

servation that amnestic MCI, when ducted on the prevalence of MCI and in an attempt to

paired with certain biomarkers, approx- the incidence of cognitively normal refine the underlying

imated the condition of AD. In fact, the persons progressing to MCI.21Y29 There etiology and, hence,

proponents believed that a certain type has been a great deal of variability in predict outcome.

of amnestic MCI coupled with bio- the prevalence figures due to method- h In the Diagnostic and

markers for the presence of amyloid ological variation in the studies and Statistical Manual of

or amyloid and tau constituted the ear- the different implementations of the Mental Disorders, Fifth

liest symptomatic stages of the AD criteria.4 For example, some of the fac- Edition, for the

process.20 The temporal evolution of tors to be considered include the general category of

the criteria for MCI and prodromal AD breadth of the MCIVsuch as all MCI, neurocognitive disorders,

are presented in Figure 2-2. amnestic MCI, nonamnestic MCIVas the criteria now include

As is apparent, sufficient overlap well as the methods of data gathering. a predementia

phase called mild

exists among these various sets of In addition, factors such as the retro-

neurocognitive disorder.

terminologies, which may reflect the spective application of criteria to pre-

reality that the core features of MCI viously collected clinical data, versus h The construct of

correspond to the earliest symptom- prospective design using established prodromal Alzheimer

disease evolved from the

atic stages of a variety of cognitive criteria and applying them as subjects

accumulating literature

disorders.4 Figure 2-3 attempts to are enrolled in the study, can affect

that had developed

characterize the common features of prevalence figures. In general, the regarding the observation

these various sets of criteria. Most of prospectively designed studies that that amnestic mild

cognitive impairment,

when paired with certain

biomarkers, approximated

the condition of

Alzheimer disease. In fact,

the proponents believed

that a certain type of

amnestic mild cognitive

impairment coupled with

biomarkers for the

presence of amyloid or

amyloid and tau

FIGURE 2-2 Temporal evolution of criteria for mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and prodromal

Alzheimer disease (AD).

constituted the earliest

symptomatic stages

DSM-5 = Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition; of the Alzheimer

NIA-AA = National Institute on AgingYAlzheimer’s Association.

disease process.

Continuum (Minneap Minn) 2016;22(2):404–418 www.ContinuumJournal.com 407

Copyright © American Academy of Neurology. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

Mild Cognitive Impairment

KEY POINTS

h The multiple sets of

criteria referring to mild

cognitive impairment

actually contain many of

the same elements and

are quite similar to the

original Key

Symposium criteria.

h Numerous international

studies have been

completed involving

several thousand

subjects, and these

studies tend to estimate

the overall prevalence

of mild cognitive

impairment in the

12% to 18% range in

persons over the age

of 60 years.

FIGURE 2-3 Comparison of common criteria used to characterize mild cognitive impairment

(MCI) in various publications. The biomarkers for amyloid-" (A") or tau could

be derived from either positron emission tomography (PET) imaging or CSF to

accompany the clinical syndromes described above.

AD = Alzheimer disease; CSF = cerebrospinal fluid; DSM-5 = Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of

Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition; FDG-PET = fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography;

MRI = magnetic resonance imaging.

Reprinted with permission from Petersen RC, et al, J Intern Med.4 onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1365-

2796.2004.01388.x/full#b36. B 2014 The Association for the Publication of the Journal of Internal Medicine.

establish criteria prior to labeling the in persons over the age of 60 years.21Y26

participants as having MCI are more The Mayo Clinic Study of Aging, which

reliable and valid. Studies that apply is a population-based study in Olmsted

MCI criteria to previously collected data County, Minnesota, found the overall

can generate a variety of figures based prevalence of MCI to be 16% in resi-

on the cutoff scores that are used to dents age 70 years and older.27 MCI is

define MCI. Therefore, since MCI is a clearly an age-related condition, and

clinical diagnosis informed by neuro- to the extent that the evaluation sug-

psychological data, a prospective study gests a degenerative etiology, AD is

is preferred when interpreting epide- most likely.30

miologic data. A similar situation pertains to the

Numerous international studies have normal cognition to MCI transition,

been completed involving several with certain methodological issues

thousand subjects, and these studies lending themselves to some of the

tend to estimate the overall preva- variation. Several longitudinal epidemi-

lence of MCI in the 12% to 18% range ologic studies have followed cognitively

408 www.ContinuumJournal.com April 2016

Copyright © American Academy of Neurology. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

KEY POINTS

normal subjects sufficiently long events, appointments, visits of friends, h The Mayo Clinic Study

enough to characterize the progression or conversations. If the patient is start- of Aging followed

rate, which also can be variable.28,31 ing to repeat himself or herself, then subjects 70 years and

The Mayo Clinic Study of Aging this is an index that some memory def- older for a median of

followed subjects 70 years and older icits are evolving. Again, the clinician 5 years and found the

for a median of 5 years and found the should focus on a change in memory progression rate of mild

progression rate to be in the 5% to 6% or cognitive function for that individual. cognitive impairment to

per year range.28 The rates are lower in Next, the clinician should explore be in the 5% to 6% per

younger subjects and rise considerably the breadth of the cognitive concern. year range.

with age. All these data speak to the Is the concern related to memory h Mild cognitive impairment

frequency of the condition of MCI alone, or does it involve memory and is not meant to reflect

and why it is important to recognize other cognitive domains such as at- lifelong low cognitive

in clinical practice. tention and concentration? Patients function; rather, it is

will often describe cognitive changes meant to reflect a change

CLINICAL EVALUATION for this individual person.

in the domain of memory when, in fact,

If a clinician adopts the flowchart they may mean attention or language h In mild cognitive

for fulfilling the criteria outlined in problems. The breadth of the cognitive impairment, the

Figure 2-1, the MCI diagnosis for a change is important to characterize. At patient’s daily function

is largely preserved.

patient can be approached as follows. this point, the clinician will need to do a

At the top of the figure, presuming the mental status examination and explore

patient presents with a cognitive con- the various cognitive domains. If time is

cern, the clinician is then faced with a limitation, a mental status assessment

the question of how to evaluate this involving an instrument such as the

symptom. Obtaining a history from Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA)

the patient and confirming this history or the Short Test of Mental Status can

with someone who knows the patient be useful, but the clinician must be

well is critical. It is important that a mindful that these screening instru-

cognitive concern is elicited either on ments are insufficient to make the

the part of the patient, the patient’s diagnosis; nevertheless, they can be

informant, or the physician. The cog- important to isolate domains of impair-

nitive concern is important since it ment and advise the clinician on further

reflects a change in the person’s perfor- assessments.32,33 If the primary ques-

mance. That is, MCI is not meant to tion with the patient concerns the dif-

reflect lifelong low cognitive function; ferentiation between the patient’s

rather, it is meant to reflect a change symptoms and the changes in cognitive

for this individual person. As such, in function seen in normal aging, neuro-

the absence of formal longitudinal cog- psychological testing can be particularly

nitive data on an individual, the clinical helpful. The neuropsychologist can

history is critical. Here, the clinician characterize the profile of cognitive

should focus on the types of cognitive function and assess whether the level

changes the patient has noted. If the of function is appropriate for the pa-

primary concern is in the memory tient’s age, sex, and education. If this is

domain, the physician should focus on not available to the clinician, then the

instances of forgetfulness that are rela- clinician must make the best estimate

tively new (ie, appearing approximately of function possible.

in the last 6 months to a year). In Other elements in the history to

particular, the physician should be in- be assessed include functional per-

terested in instances of forgetful- formance, which, in a patient with

ness involving recently experienced MCI, should indicate that the patient’s

Continuum (Minneap Minn) 2016;22(2):404–418 www.ContinuumJournal.com 409

Copyright © American Academy of Neurology. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

Mild Cognitive Impairment

daily function is largely preserved. The ease is a likely candidate. Alternatively,

patient may be inefficient at doing if the patient has a history of vascu-

certain tasks and may take more time lar risk factors and has experienced

but ultimately can do them without any cerebral ischemic events, a vascular

assistance. This type of assessment ful- contribution needs to be considered.

fills the preserved cognitive function In addition, some aspects of psychiat-

aspect of the criteria. This can be a very ric conditions such as major depres-

subjective assessment, and here, a re- sion or generalized anxiety disorder can

liable informant can be helpful. How- have cognitive components, and con-

ever, if the person is still functioning sequently, in the early stages of these

in daily life, driving, paying bills, doing disorders, cognition may be impaired.

taxes, and to the casual observer ap- The clinician must always consider

pears normal, generally speaking, func- other medical conditions such as un-

tion is preserved. Finally, given all of compensated heart failure, poorly con-

these considerations, the patient does trolled diabetes mellitus, or chronic

not meet criteria for dementia. That obstructive pulmonary disease as

is, the person’s cognitive impairments contributors to cognitive impairment.

are not of sufficient severity to compro- Some of these medical comorbidities

mise daily functioning. Hence, the chief may be treatable, and their medica-

criterion for dementia is not met. tions may play a role in the clinical

The clinician following the flow- syndrome as well.

chart in Figure 2-1 should determine If the clinician believes that a de-

whether the person has experienced a generative condition is most likely the

change in cognition, whether there is underlying explanation, then the clin-

some objective corroboration of this, ical syndromes can be useful in sug-

whether function is relatively well pre- gesting an underlying diagnosis. If

served, and whether the patient does the patient appears to have a typical

or does not meet criteria for dementia. amnestic syndrome leading to MCI and

If MCI is determined to be a reasonable is in the appropriate age range, AD is a

diagnosis, the clinician then needs to likely consideration. However, if the

determine if memory is a salient part of patient is experiencing attention, con-

the cognitive impairment, and if so, the centration, and visuospatial difficulties,

arm in the diagram in Figure 2-1 that a forme fruste of dementia with Lewy

outlines amnestic MCI would be ap- bodies might be considered, and if

propriate. If, however, the person is the person is experiencing behavioral

experiencing a cognitive decline but changes, inappropriate behavior, apa-

memory is relatively well preserved, thy, lack of insight, and attention and

then the nonamnestic arm of the dia- concentration are impaired, fronto-

gram would apply. temporal lobar degeneration may be

After the clinical syndrome has been possible. Of course, the most common

determined, as outlined above, then degenerative disease of aging, AD, can

the clinician needs to determine the have atypical presentations involving

cause or etiology of that syndrome. attention, concentration, and language.

Figure 2-1 characterizes possible ex- Based on the history and the exam-

planations of the various clinical syn- ination, the clinician may be able to

dromes and can help determine the make a likely supposition regarding

further diagnostic workup. If the his- the nature of the condition. At this

tory of the onset of the disorder is point, further testing such as an MRI

slow and gradual, a degenerative dis- scan, fluorodeoxyglucose positron

410 www.ContinuumJournal.com April 2016

Copyright © American Academy of Neurology. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

KEY POINT

emission tomography (FDG-PET) or gression, and many imaging and fluid h Several studies have

positron emission tomography (PET) biomarker studies.30,34 The Alzheimer’s indicated that individuals

for amyloid imaging along with a CSF Disease Neuroimaging Initiative with mild cognitive

analysis could be considered. These (ADNI) has been very active for the impairment who have a

further assessments may assist in past 10 years evaluating individuals positive amyloid positron

depicting the underlying etiology of with amnestic MCI who have been emission tomography

the clinical syndromes. While no phar- followed for several years. These data scan are more likely to

macologic therapies are currently ap- as well as others indicate that, in progress rapidly, which is

proved by the US Food and Drug general, medial temporal lobe atrophy confirmed by data from

Administration (FDA) for MCI due to on MRI tends to predict progres- the Alzheimer’s Disease

sion as does a hypometabolic pattern Neuroimaging Initiative.

AD, lifestyle modifications and cogni-

tive and behavioral therapies can be consistent with AD on FDG-PET.34Y37

useful. Also, counseling patients on Figure 2-4 shows individuals who are

expectations can be quite important. cognitively normal along with those

The contribution of medical comor- who have MCI and those who have

bidities, as outlined previously, in- dementia on MRI scans, FDG-PET,

cluding sleep disorders such as sleep amyloid PET, and the newest imaging

apnea, also need to be considered modality, tau PET. Several studies have

since some of these have treatable indicated that individuals with MCI

components (Case 2-1B). who have a positive amyloid PET scan

are more likely to progress rapidly and,

PREDICTORS OF PROGRESSION again, ADNI data confirm this.38,39

There has been a great deal of data For many years, it has been known

generated in recent years concern- that carriers of the apolipoprotein E4

ing the progression of persons diag- (APOE4) genotype are more likely to

nosed with MCI. In particular, there progress rapidly, and this has been

are clinical variables such as severity of borne out in numerous studies; how-

cognitive impairment that predict pro- ever, in clinical practice APOE testing

Case 2-1B

A mental status examination was performed on the 66-year-old patient

discussed in Case 2-1A, and while the patient did quite well, there was a

suggestion of memory impairment with impaired delayed recall of the

words. Neuropsychological testing was pursued, which showed a profile

that looked normal for his age, sex, and education in virtually all cognitive

domains except for memory. Here, his delayed recall of lists, paragraphs,

and nonverbal materials was mildly impaired.

Further interview of the patient and a family member revealed that

his function was largely preserved. In particular, he functioned in the

community quite well without difficulty, and while slightly more inefficient

at some tasks, he still completed everything quite well.

Comment. Based on examination findings, neuropsychological testing,

and discussions with the patient and his family member, he does not

appear to have dementia. A reasonable diagnosis at this point would be

amnestic mild cognitive impairment, but the etiology, given the patient’s

young age and negative family history, is uncertain. At this point, a

discussion with the patient might include possible etiologies and education

about lifestyle alterations, planning for the future, and consideration of

enrollment in randomized controlled trials.

Continuum (Minneap Minn) 2016;22(2):404–418 www.ContinuumJournal.com 411

Copyright © American Academy of Neurology. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

Mild Cognitive Impairment

FIGURE 2-4 Progression of imaging features from cognitively

normal to mild cognitive impairment to dementia.

FDG-PET = fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission

tomography; MRI = magnetic resonance imaging;

PET = positron emission tomography.

does not add significantly to the diag- tia.42,43 The 2006 study by Hansson

nostic evaluation.34,40 and colleagues44 was most informative

The newest PET tracer that is emerg- with regard to these data and corrob-

ing allows investigators to evaluate the orates the suspicion that those indi-

role of tau in clinical progression, and viduals, particularly with amnestic

these data are evolving.41 It is quite MCI, who harbor low CSF levels of

likely that a tau PET scan that shows A"42 and elevated total tau and phos-

the spread of tau outside of the me- phorylated tau are at an increased risk

dial temporal lobe into lateral tempo- for progressing more rapidly than

ral lobe structures portends a poorer those subjects with the same clinical

prognosis and, more likely, a rapid phenotype but normal CSF biomarkers.

progression from MCI to AD demen- In general, these predictors all refer

tia, but these data need to be ampli- to individuals who are on the AD spec-

fied (Figure 2-4). trum. Biomarkers for other degenera-

Numerous studies have shown that tive disorders are less certain at this

the various CSF markers consistent with point and need to be fully evaluated.

AD predict progression to AD demen- As biomarkers for other disorders

412 www.ContinuumJournal.com April 2016

Copyright © American Academy of Neurology. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

KEY POINTS

evolve, it is likely that they will be the term neurocognitive disorder is h The National Institute

matched with a particular phenotype used for the syndromes of cognitive on Aging and the

of MCI and increase the ability to impairment irrespective of specific Alzheimer’s Association

predict the clinical outcome. etiology.17 The spectrum was divided divided the Alzheimer

into mild neurocognitive disorder, disease spectrum into

CRITERIA FOR MILD COGNITIVE which is very similar to MCI, and major three overlapping areas:

IMPAIRMENT DUE TO neurocognitive disorder, which is very preclinical Alzheimer

ALZHEIMER DISEASE similar to dementia. The criteria for disease in which

mild neurocognitive disorder essen- individuals are clinically

The NIA and the Alzheimer’s Associa-

tially incorporate the MCI criteria from normal but possess

tion convened groups of experts to

biomarker evidence for

revise the criteria for AD across the the Key Symposium in 2004 and sug-

the Alzheimer disease

spectrum.8 The groups divided the AD gest that, as data accumulate, speci-

process, mild cognitive

spectrum into three overlapping areas: ficity of etiology will be added through impairment due to

preclinical AD in which individuals are the use of biomarkers. After the syn- Alzheimer disease

clinically normal but possess biomarker drome of either mild or major neuro- whereby individuals meet

evidence for the AD process, MCI due cognitive disorder is made, DSM-5 then the clinical criteria for

to AD whereby individuals meet the gives recommendations as to how the mild cognitive impairment

clinical criteria for MCI and have varying clinician can determine the underlying and have varying levels

levels of biomarker specificity for AD, etiology of the syndrome.17 As such, of biomarker specificity

conditions such as AD, frontotemporal for Alzheimer disease,

and AD dementia in which individuals and AD dementia in

lobar degeneration, dementia with Lewy

meet clinical criteria for dementia and which individuals meet

bodies, vascular cognitive impairment,

similarly have varying degrees of bio- clinical criteria for

human immunodeficiency (HIV)-related

marker support.1 These criteria have dementia and similarly

disorders, alcohol and substance abuse,

proved useful in characterizing the en- have varying degrees of

Parkinson disease, and a variety of other biomarker support.

tire spectrum of AD and expanding it

possible etiologies are explicated. As

beyond the dementia phase. Prior sets h The spectrum of

noted above, the process of combining

of criteria had focused only on the de- the clinical syndrome with patient his-

neurocognitive disorder,

mentia phase, but it has become ap- as defined by the

tory, clinical examination findings, and, Diagnostic and Statistical

parent in recent years that the AD while still evolving, biomarker informa- Manual of Mental

process likely begins years and per- tion is used to specify the clinical syn- Disorders, Fifth Edition, is

haps decades before clinical symp- drome. As is seen in DSM-5, there are divided into mild

toms appear.45 As such, the use of often degrees of certainty added to the neurocognitive disorder,

biomarkers has afforded an important clinical diagnoses based on the pre- which is very similar

tool for specificity for the clinician. It ponderance of evidence for a specific to mild cognitive

must be emphasized, however, that underlying disorder.17 impairment, and major

these criteria involving biomarkers are In 2007 and updated in 2010 and neurocognitive disorder,

still in the research phase, and specific 2013, investigators have proposed the which is very similar

recommendations regarding their use to dementia.

term prodromal AD as an alternative

in clinical practice remain to be deter- for characterizing individuals along

mined. However, based on the litera- the AD spectrum.18Y20 The most re-

ture cited above, it is apparent that the cent version of these criteria embod-

use of biomarkers is working its way ies the notion of amnestic MCI and

into clinical practice. embellishes it with evidence for amy-

In addition, the American Psychiatric loid deposition via PET scanning or

Association has recently published the amyloid and tau information using

DSM-5, and this set of criteria gives CSF.20 These investigators contend

consideration to the diagnosis of mild that the combination of amnestic MCI

neurocognitive disorder. In general, with specific biomarkers is highly

Continuum (Minneap Minn) 2016;22(2):404–418 www.ContinuumJournal.com 413

Copyright © American Academy of Neurology. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

Mild Cognitive Impairment

KEY POINTS

h Currently, there are no suggestive of the AD process and should ever, subsequent data suggest that

accepted pharmacologic be labeled as AD. These criteria have there may be some efficacy to be

treatments for mild been useful for randomized control gleaned from lifestyle modifications,

cognitive impairment trials for evaluation of pharmacologic and these need to be explored further.

approved by the US therapeutics intended to target under-

Food and Drug lying AD pathophysiology.46,47 CLINICAL ACCEPTANCE

Administration, the The construct of MCI has been in the

European Medicines TREATMENTS medical literature for many years and,

Agency, or the Currently, there are no accepted phar- over time, has been accepted in clin-

Pharmaceuticals and ical practice to certain degrees. The

macologic treatments for MCI ap-

Medical Devices Agency

proved by the FDA, the European American Academy of Neurology

in Japan.

Medicines Agency, or the Pharmaceu- (AAN) completed an evidence-based

h Lifestyle modifications ticals and Medical Devices Agency in medicine review of the literature and

and other

Japan. Numerous randomized control concluded that the construct of MCI is

nonpharmacologic

trials have been conducted in the MCI useful for clinicians to identify since

therapies have also

been investigated, and spectrum, but none has been success- the condition does lead to a higher

there is a suggestion ful at demonstrating effectiveness at risk of progression to dementia.50

that some of these delaying the progression from MCI to Numerous epidemiologic studies have

modifications or AD dementia.10Y14 One of the first been done around the world that have

therapies, such as trials, conducted by the Alzheimer’s suggested the utility of the identi-

aerobic exercise, may Disease Cooperative Study, evaluated fication of MCI as a clinical entity.

be effective at reducing donepezil and high-dose vitamin E in Roberts and colleagues51 evaluated

the rate of progression amnestic MCI.13 This study indicated members of the Behavioral Neurology

from mild cognitive that donepezil may be effective at section and the Geriatric Neurology

impairment to dementia. section of the AAN and documented

slowing the rate of progression in all

h Criticism has been subjects with amnestic MCI for the that MCI is used frequently in clinical

raised regarding the first year of the trial and perhaps up to practice and that practitioners find the

boundaries of the construct useful. There were concerns

2 years in subjects with amnestic MCI

condition of mild about its specificity and the lack of

who were positive for the APOE4 iso-

cognitive impairment treatments, but, nevertheless, it was

with respect to

form. However, since the study was

designed to continue for 36 months, believed to be useful.

differentiating it from

no treatments demonstrated effective- Recently, a similar exercise was done

changes of cognitive

aging and also ness at that time and, as such, the trial in Europe assessing the utility of the

differentiating it was negative. Other studies involving construct of MCI in clinical practice and

from dementia. cholinesterase inhibitors that have the outcome was quite similar to that

been used for the treatment of AD found in polling members of the AAN.

dementia were also unsuccessful.10,11,13 As such, it appears that the construct of

Lifestyle modifications and other MCI is accepted in clinical practice and

nonpharmacologic therapies have also serves a function for clinicians in com-

been investigated, and there is a municating clinical diagnoses to pa-

suggestion that some of these modifi- tients. It has also been a useful construct

cations or therapies, such as aerobic for research as literally thousands of

exercise, may be effective at reducing studies have been generated in the

the rate of progression from MCI to past decade assessing various aspects

dementia.48 However, a state-of-the- of the condition.

science report from the National Insti- This is not to say, however, that there

tutes of Health (NIH) in 2010 failed to is not controversy surrounding the con-

document any successful interventions struct. Criticism has been raised regard-

for progression to dementia.49 How- ing the boundaries of the condition

414 www.ContinuumJournal.com April 2016

Copyright © American Academy of Neurology. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

with respect to differentiating MCI CONCLUSION

from changes of cognitive aging and MCI has become an important topic in

also from dementia. Since cognitive clinical practice and research. With the

changes with aging are believed to be emphasis on earlier identification of

common, it can be challenging to de- incipient forms of cognitive deficits,

termine whether a particular person is MCI put boundaries on this intermedi-

experiencing those changes or the ate state. Numerous randomized con-

forme fruste of MCI. A recent publica- trolled trials are underway for the MCI

tion from the Institute of Medicine has subtype due to AD, and clinicians need

characterized the expectations of cog- to be aware of these research opportu-

nitive aging, and a distinction is made nities for their patients. As treatable

between these changes and those that etiologies of MCI are identified (such

represent incipient MCI.52 However, as those due to psychiatric conditions,

there is a great deal of variability in medications, or medical comorbidities),

the literature regarding MCI, and many the cognitive deficits may be reversible.

of these features have been reviewed Biomarker development should pro-

recently.4 There have been controver- vide the clinician with new tools to

sies regarding the implementation of identify and hopefully treat MCI.

MCI criteria involving neuropsycho-

logical tests, cutoff scores, types of ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

measures, and cross-sectional versus

The author receives grant support

longitudinal assessment. There has

from the National Institute on Aging

been variability in methodology of

(P50 AG016574, U01 AG006786, U01

studies including the subjects sampled

AG024904, R01 AG011378, and R01

for the studies, how they were evalu-

AG041581).

ated (eg, prospectively or retrospec-

tively), and the availability of normative

data against which to make compari- REFERENCES

1. Jack CR Jr, Albert MS, Knopman DS, et al.

sons for cognitive performance. All of

Introduction to the recommendations from

these issues, and more, are very salient the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s

and require the clinician to use judg- Association workgroups on diagnostic

ment in characterizing individuals guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease.

Alzheimer’s & dementia: the journal of the

with MCI. Nevertheless, a potential Alzheimer’s Association 2011;7(3):257Y262.

asset of a condition such as MCI will doi:10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.004.

be validated when effective treatments 2. Petersen RC. Mild cognitive impairment as a

are developed, particularly for MCI diagnostic entity. J Intern Med 2004;256(3):

due to AD. 183Y194. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2796.2004.01388.x.

No doubt, there will be additional 3. Petersen RC. Clinical practice. Mild cognitive

research generated regarding the con- impairment. N Engl J Med 2011;364(23):

2227Y2234. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp0910237.

struct of MCI, and these data should

help clarify many of the issues sur- 4. Petersen RC, Caracciolo B, Brayne C, et al.

Mild cognitive impairment: a concept in

rounding uncertainty. The clinicians evolution. J Intern Med 2014;275(3):

must recognize that these arbitrary 214Y228. doi:10.1111/joim.12190.

distinctions in clinical state, particularly 5. Reisberg B, Ferris S, de Leon MJ. Stage-specific

when dealing with underlying degen- behavioral, cognitive, and in vivo changes

erative conditions and their continua, in community residing subjects with

age-associated memory impairment and

are artificial. Nevertheless, in communi-

primary degenerative dementia of the

cating with patients and with other clin- Alzheimer type. Drug Dev Res 1988;

icians, these constructs can be useful. 15(2Y3):101Y114. doi:10.1002/ddr.430150203.

Continuum (Minneap Minn) 2016;22(2):404–418 www.ContinuumJournal.com 415

Copyright © American Academy of Neurology. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

Mild Cognitive Impairment

6. Petersen RC, Smith GE, Waring SC, et al. 16. Sperling RA, Aisen PS, Beckett LA, et al.

Mild cognitive impairment: clinical Toward defining the preclinical stages of

characterization and outcome. Arch Neurol Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from

1999;56(3):303Y308. doi:10.1001/ the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s

archneur.56.3.303. Assocation workgroups on diagnostic

guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease.

7. Winblad B, Palmer K, Kivipelto M, et al.

Alzheimers Dement 2011;7(3):280Y292.

Mild cognitive impairmentVbeyond doi:10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.003.

controversies, towards a consensus: report

of the International Working Group on 17. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic

Mild Cognitive Impairment. J Intern Med and statistical manual of mental disorders,

2004;256(3):240Y246. doi:10.1111/ fifth edition. Washington, DC: American

j.1365-2796.2004.01380.x. Psychiatric Publishing, 2013.

8. Petersen RC. Mild Cognitive Impairment. 18. Dubois B, Feldman HH, Jacova C, et al. Research

Continuum (Minneap Minn) 2004; criteria for the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s

10(1 Dementia):9Y28. doi:10.1212/ disease: revising the NINCDS-ADRDA criteria.

01.CON.0000293545.39683.cc. Lancet Neurol 2007;6(8):734Y746. doi:10.1016/

S1474-4422(07)70178-3.

9. Albert MS, DeKosky ST, Dickson D, et al.

The diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment 19. Dubois B, Feldman HH, Jacova C, et al. Revising

due to Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations the definition of Alzheimer’s disease: a new

from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s lexicon. Lancet Neurol 2010;9(11):1118Y1127.

Association workgroups on diagnostic doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(10)70223-4.

guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers 20. Dubois B, Feldman HH, Jacova C, et al.

Dement 2011;7(3):270Y279. doi:10.1016/ Advancing research diagnostic criteria for

j.jalz.2011.03.008. Alzheimer’s disease: the IWG-2 criteria.

10. Doody RS, Ferris SH, Salloway S, et al. Lancet Neurol 2014;13(6):614Y629.

Donepezil treatment of patients with MCI: a doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(14)70090-0.

48-week randomized, placebo-controlled 21. Busse A, Hensel A, Gühne U, et al. Mild

trial. Neurology 2009;72(18):1555Y1561. cognitive impairment: long-term course of

doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000344650.95823.03. four clinical subtypes. Neurology

2006;67(12):2176Y2185. doi:10.1212/

11. Feldman HH, Ferris S, Winblad B, et al.

01.wnl.0000249117.23318.e1.

Effect of rivastigmine on delay to diagnosis

of Alzheimer’s disease from mild cognitive 22. Di Carlo A, Lamassa M, Baldereschi M, et al.

impairment: the InDDEx study. Lancet CIND and MCI in the Italian elderly:

Neurol 2007;6(6):501Y512. doi:10.1016/ frequency, vascular risk factors, progression

S1474-4422(07)70109-6. to dementia. Neurology 2007;68(22):

1909Y1916. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.

12. Thal LJ, Ferris SH, Kirby L, et al. A randomized,

0000263132.99055.0d.

double-blind, study of rofecoxib in patients

with mild cognitive impairment. 23. Ganguli M, Chang CC, Snitz BE, et al.

Neuropsychopharmacology 2005;30(6): Prevalence of mild cognitive impairment

1204Y1215. doi:10.1038/sj.npp.1300690. by multiple classifications: The

Monongahela-Youghiogheny Healthy Aging

13. Winblad B, Gauthier S, Scinto L, et al.

Team (MYHAT) project. Am J Geriatr

Safety and efficacy of galantamine in

Psychiatry 2010;18(8):674Y683. doi:10.1097/

subjects with mild cognitive impairment.

JGP.ob013e3181cdee4f.

Neurology 2008;70(22):2024Y2035.

doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000303815. 24. Larrieu S, Letenneur L, Orgogozo JM, et al.

69777.26. Incidence and outcome of mild cognitive

impairment in a population-based prospective

14. Petersen RC, Thomas RG, Grundman M,

cohort. Neurology 2002;59(10):1594Y1599.

et al. Vitamin E and donepezil for the

doi:10.1212/01.WNL.0000034176.07159.F8.

treatment of mild cognitive impairment. N

Engl J Med 2005;352(23):2379Y2388. 25. Lopez OL, Jagust WJ, DeKosky ST, et al.

doi:10.1056/NEJMoa050151. Prevalence and classification of mild cognitive

impairment in the Cardiovascular Health

15. McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H,

Study Cognition Study: part 1. Arch Neurol

et al. The diagnosis of dementia due to

2003;60(10):1385Y1389. doi:10.1001/

Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from

archneur.60.10.1385.

the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s

Association workgroups on diagnostic 26. Manly JJ, Tang MX, Schupf N, et al. Frequency

guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. and course of mild cognitive impairment in

Alzheimers Dement 2011;7(3):263Y269. a multiethnic community. Ann Neurol

doi:10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.005. 2008;63(4):494Y506. doi:10.1002/ana.21326.

416 www.ContinuumJournal.com April 2016

Copyright © American Academy of Neurology. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

27. Petersen RC, Roberts RO, Knopman DS, et al. 38. Prestia A, Caroli A, van der Flier WM, et al.

Prevalence of mild cognitive impairment is Prediction of dementia in MCI patients based

higher in men. The Mayo Clinic Study of on core diagnostic markers for Alzheimer

Aging. Neurology 2010;75(10):889Y897. disease. Neurology 2013;80(11):1048Y1056.

doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181f11d85. doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182872830.

28. Roberts RO, Geda YE, Knopman DS, 39. Petersen RC, Aisen P, Boeve BF, et al. Mild

et al. The incidence of MCI differs by cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer

subtype and is higher in men: the Mayo disease in the community. Ann Neurol

Clinic Study of Aging. Neurology 2013;74(2):199Y208. doi:10.1002/ana.23931.

2012;78(5):342Y351. doi:10.1212/WNL. 40. Petersen RC, Smith GE, Ivnik RJ, et al.

0b013e3182452862. Apolipoprotein E status as a predictor of the

29. Unverzagt FW, Gao S, Baiyewu O, et al. development of Alzheimer’s disease in

memory-impaired individuals. JAMA

Prevalence of cognitive impairment: data

1995;273(16):1274Y1278. doi:10.1001/

from the Indianapolis Study of Health and

jama.1995.03520400044042.

Aging. Neurology 2001;57(9):1655Y1662.

doi:10.1212/WNL.57.9.1655. 41. Johnson KA, Schultz A, Betensky RA, et al.

Tau positron emission tomographic imaging

30. Okello A, Koivunen J, Edison P, et al. in aging and early Alzheimer disease. Ann

Conversion of amyloid positive and negative Neurol 2016;79(1):110Y119. doi:10.1002/

MCI to AD over 3 years: An 11C-PIB PET ana.24546.

Study. Neurology 2009;73(10):754Y760.

doi:10.1212/WNL.ob013e3181b23564. 42. Mattsson N, Insel PS, Donohue M, et al.;

Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative.

31. Lopez OL, Becker JT, Chang YF, et al. Predicting reduction of cerebrospinal fluid

Incidence of mild cognitive impairment "-amyloid 42 in cognitively healthy controls.

in the Pittsburgh Cardiovascular Health JAMA Neurol 2015;72(5):554Y560.

Study-Cognition Study. Neurology doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2014.4530.

2012;79(15):1599Y1606. doi:10.1212/

43. Mattsson N, Zetterberg H, Hansson O, et al.

WNL.0b013e31826e25f0.

CSF biomarkers and incipient Alzheimer

32. Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bédirian V, et al. disease in patients with mild cognitive

The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: impairment. JAMA 2009;302(4):385Y393.

a brief screening tool for mild cognitive doi:10.1001/jama.2009.1064.

impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc 2005;53(4):695Y699.

44. Hansson O, Zetterberg H, Buchhave P, et al.

doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53221.x.

Association between CSF biomarkers and

33. Kokmen E, Naessens JM, Offord KP. incipient Alzheimer’s disease in patients

A short test of mental status: description with mild cognitive impairment: a follow-up

and preliminary results. Mayo Clin Proc study. Lancet Neurol 2006;5(3):228Y234.

1987;62(4):281Y288. doi:10.1016/ doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(06)70355-6.

S0025-6196(12)61905-3.

45. Rowe CC, Ng S, Ackermann U, et al. Imaging

34. Weiner MW, Veitch DP, Aisen PS, et al.; beta-amyloid burden in aging and dementia.

Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. Neurology 2007;68(20):1718Y1725.

Impact of the Alzheimer’s Disease doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000261919.22630.ea.

Neuroimaging Initiative, 2004 to 2014.

46. Perry D, Sperling R, Katz R, et al. Building a

Alzheimers Dement 2015;11(7):865Y884.

roadmap for developing combination

doi:10.1016/j.jalz.2015.04.005.

therapies for Alzheimer’s disease. Expert Rev

35. Dickerson BC, Salat DH, Greve DN, et al. Neurother 2015;15(3):327Y333. doi:10.1586/

Increased hippocampal activation in mild 14737175.2015.996551.

cognitive impairment compared to

47. Romero K, Ito K, Rogers JA, et al.;

normal aging and AD. Neurology

Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative;

2005;65(3):404Y411. doi:10.1212/

Coalition Against Major Diseases. The

01.wnl.0000171450.97464.49.

future is now: model-based clinical trial

36. Landau SM, Harvey D, Madison CM, et al. design for Alzheimer’s disease. Clin

Comparing predictors of conversion and Pharmacol Ther 2015;97(3):210Y214.

decline in mild cognitive impairment. doi:10.1002/cpt.16.

Neurology 2010;75(3):230Y238. doi:10.1212/

48. Lautenschlager NT, Cox KL, Flicker L, et al.

WNL.0b013e3181e8e8b8. Effect of physical activity on cognitive

37. Landau SM, Mintun MA, Joshi AD, et al. function in older adults at risk for

Amyloid deposition, hypometabolism, and Alzheimer disease: a randomized trial.

longitudinal cognitive decline. Ann Neurol JAMA 2008;300(9):1027Y1037.

2012;72(4):578Y586. doi:10.1002/ana.23650. doi:10.1001/jama.300.9.1027.

Continuum (Minneap Minn) 2016;22(2):404–418 www.ContinuumJournal.com 417

Copyright © American Academy of Neurology. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

Mild Cognitive Impairment

49. National Institute of Health Office of the Academy of Neurology. Neurology

Director. NIH state-of-the-science conference 2001;56(9):1133Y1142. doi:10.1212/

statement on preventing Alzhimer’s disease WNL.56.9.1133.

and cognitive decline. Volume 27, number 4. 51. Roberts JS, Karlawish JH, Uhlmann WR, et al.

Updated April 26Y28, 2010. Accessed Mild cognitive impairment in clinical care: a

February 9, 2016. consensus.nih.gov/2010/ survey of American Academy of Neurology

docs/alz/alz_stmt.pdf. members. Neurology 2010;75(5):425Y431.

50. Petersen RC, Stevens JC, Ganguli M, et al. doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181eb5872.

Practice parameter: early detection of 52. Institute of Medicine. Cognitive aging: progress

dementia: mild cognitive impairment (an in understanding and opportunities for action.

evidence-based review). Report of the Quality Washington, DC: The National Academies

Standards Subcommittee of the American Press, 2015.

418 www.ContinuumJournal.com April 2016

Copyright © American Academy of Neurology. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

You might also like

- Bipolar Disorder Implications For Nursing PracticeDocument5 pagesBipolar Disorder Implications For Nursing PracticeFátima Lopes100% (2)

- Surrogacy AgreementDocument29 pagesSurrogacy AgreementMacduff RonnieNo ratings yet

- Reading ComprehensionDocument42 pagesReading Comprehension14markianneNo ratings yet

- Chest X-RayDocument125 pagesChest X-RayRusda Syawie100% (1)

- AbPsy ReviewerDocument70 pagesAbPsy ReviewerAdam VidaNo ratings yet

- CS HF Directory 2018 Print PDFDocument80 pagesCS HF Directory 2018 Print PDFAt Day's WardNo ratings yet

- Acne and Whey Protein Supplementation Among Bodybuilders PDFDocument4 pagesAcne and Whey Protein Supplementation Among Bodybuilders PDFHenyta TsuNo ratings yet

- Borderline Personality DisorderDocument8 pagesBorderline Personality DisorderVarsha Ganapathi100% (1)

- Progressive Myoclonic Epilepsies - Practical Neurology 2015. MalekDocument8 pagesProgressive Myoclonic Epilepsies - Practical Neurology 2015. MalekchintanNo ratings yet

- Approach To Neurologic InfectionsDocument18 pagesApproach To Neurologic InfectionsHabib G. Moutran Barroso100% (1)

- Narrative Report On School Nursing - EditedDocument16 pagesNarrative Report On School Nursing - EditedAbby_Cacho_9151100% (2)

- Seminar on Concepts and Foundations of RehabilitationDocument13 pagesSeminar on Concepts and Foundations of Rehabilitationamitesh_mpthNo ratings yet

- 515Document972 pages515solecitodelmarazul100% (6)

- Orthopedic Nursing. Lecture Notes at Philipine Orthopedic CenterDocument7 pagesOrthopedic Nursing. Lecture Notes at Philipine Orthopedic Centerhannjazz100% (5)

- Kepler and AlchemyDocument13 pagesKepler and AlchemyMartha100% (1)

- Ni Hms 613426Document13 pagesNi Hms 613426ArdianNo ratings yet

- 2009 Peterson Mild Cognitive Impairment. Ten Years LaterDocument9 pages2009 Peterson Mild Cognitive Impairment. Ten Years LaterMario BertaNo ratings yet

- SFP-Vol351supp Unit2Document5 pagesSFP-Vol351supp Unit2Fazeah MusaNo ratings yet

- Early Alzheimer's Disease: Clinical PracticeDocument8 pagesEarly Alzheimer's Disease: Clinical Practicemarcolin0No ratings yet

- Early Alzheimer's Disease: Clinical PracticeDocument8 pagesEarly Alzheimer's Disease: Clinical PracticeedgararrazolaNo ratings yet

- Alzheimer Early 2010Document8 pagesAlzheimer Early 2010Matchas MurilloNo ratings yet

- Review: Tamara G Fong, Daniel Davis, Matthew E Growdon, Asha Albuquerque, Sharon K InouyeDocument10 pagesReview: Tamara G Fong, Daniel Davis, Matthew E Growdon, Asha Albuquerque, Sharon K InouyeAndi Mahifa 93No ratings yet

- Mild Cognitive Impairment: Clinical PracticeDocument8 pagesMild Cognitive Impairment: Clinical PracticeKristineNo ratings yet

- 2009burns DementiaDocument5 pages2009burns DementiaLucas MontanhaNo ratings yet

- Jurnal DR ZainiDocument12 pagesJurnal DR ZainiFarhan Hady DanuatmajaNo ratings yet

- The Interface Between Delirium and Dementia in Elderly AdultsDocument10 pagesThe Interface Between Delirium and Dementia in Elderly AdultsRestuti HandayaniNo ratings yet

- Ni Hms 629964Document27 pagesNi Hms 629964ArdianNo ratings yet

- Kwan 2001Document7 pagesKwan 2001Eliška VýborováNo ratings yet

- A Rare Case of Early-Onset Bipolar Affective Disorder During LockdownDocument1 pageA Rare Case of Early-Onset Bipolar Affective Disorder During LockdownRupinder GillNo ratings yet

- Case 3Document7 pagesCase 3Lorelyn Santos CorpuzNo ratings yet

- A Rare Case of Early Onset Bipolar Affective Disorder During LockdownDocument1 pageA Rare Case of Early Onset Bipolar Affective Disorder During LockdownRupinder GillNo ratings yet

- Artigo AlzheimerDocument21 pagesArtigo Alzheimerbeatriz assunesNo ratings yet

- socioeconomic inequalities in healthDocument6 pagessocioeconomic inequalities in healthstefgerosaNo ratings yet

- Quantifying Variability in MCI DiagnosesDocument12 pagesQuantifying Variability in MCI DiagnosesMario BertaNo ratings yet

- Development RegessionDocument7 pagesDevelopment RegessionGayanNo ratings yet

- Cognitive debiasing strategies to improve diagnostic reasoningDocument7 pagesCognitive debiasing strategies to improve diagnostic reasoningJefferson ChavesNo ratings yet

- DFT2019Document25 pagesDFT2019Consulta externa Clinica montserratNo ratings yet

- Muneer Et Al., 2016 - Staging Models in Bipolar Disorder A Systematic Review of The LiteratureDocument14 pagesMuneer Et Al., 2016 - Staging Models in Bipolar Disorder A Systematic Review of The LiteraturePatrícia GrilloNo ratings yet

- Case Presentation (GRP 1, 3BSN13) Ad (1NCP)Document7 pagesCase Presentation (GRP 1, 3BSN13) Ad (1NCP)Lorelyn Santos CorpuzNo ratings yet

- Mja 250553Document6 pagesMja 250553Marcelita DuwiriNo ratings yet

- Beelen 2009Document7 pagesBeelen 2009isabela echeverriNo ratings yet

- Cognitive Impairment in Heart FailureDocument17 pagesCognitive Impairment in Heart Failureguille.1492No ratings yet

- Diabetes and Brain Health 2: Type 2 Diabetes and Cognitive Dysfunction-Towards Effective Management of Both ComorbiditiesDocument11 pagesDiabetes and Brain Health 2: Type 2 Diabetes and Cognitive Dysfunction-Towards Effective Management of Both ComorbiditiesAndreaPacsiNo ratings yet

- Exercising The Brain To Avoid Cognitive Decline: Examining The EvidenceDocument21 pagesExercising The Brain To Avoid Cognitive Decline: Examining The EvidenceRirisNo ratings yet

- El Arte de Manejar La DemenciaDocument11 pagesEl Arte de Manejar La DemenciaAgustin Alonso RodriguezNo ratings yet

- 2017 - Clinical and Demographic Predictors of Conversion To Dementia in Mexican Elderly With Mild Cognitive ImpairmentDocument7 pages2017 - Clinical and Demographic Predictors of Conversion To Dementia in Mexican Elderly With Mild Cognitive ImpairmentRaúl VerdugoNo ratings yet

- Functional Status in The Elderly With InsomniaDocument8 pagesFunctional Status in The Elderly With InsomniaNur Fauzi RomdonNo ratings yet

- Alternatives To Psychiatric DiagnosisDocument3 pagesAlternatives To Psychiatric Diagnosisfabiola.ilardo.15No ratings yet

- Idusohan Moizer2013Document12 pagesIdusohan Moizer2013patricia lodeiroNo ratings yet

- Assessing The Progression of Mild CognitDocument9 pagesAssessing The Progression of Mild CognitFábio VinholyNo ratings yet

- Tuokko DCL To DemenciaDocument23 pagesTuokko DCL To DemenciaRAYMUNDO ARELLANONo ratings yet

- Artigo EsquizofreniaDocument26 pagesArtigo EsquizofreniaJulio CesarNo ratings yet

- HHS Public Access: Cognitive Decline and Dementia in Diabetes: Mechanisms and Clinical ImplicationsDocument27 pagesHHS Public Access: Cognitive Decline and Dementia in Diabetes: Mechanisms and Clinical ImplicationsSaddam FuadNo ratings yet

- The Psychosocial Burden of Epilepsy: Gus A. BakerDocument5 pagesThe Psychosocial Burden of Epilepsy: Gus A. BakerGretelMartinezNo ratings yet

- Promotion of Cognitive Health Through Cognitive Activity in The Aging PopulationDocument11 pagesPromotion of Cognitive Health Through Cognitive Activity in The Aging PopulationMateiNo ratings yet

- ALZHEIMERDocument2 pagesALZHEIMERLorelyn Santos CorpuzNo ratings yet

- Sundown Syndrome in Older Persons A Scoping ReviewDocument13 pagesSundown Syndrome in Older Persons A Scoping ReviewBlackthestralNo ratings yet

- International Experts Reach Consensus on Mild Cognitive Impairment DefinitionDocument7 pagesInternational Experts Reach Consensus on Mild Cognitive Impairment DefinitionRoxana SanduNo ratings yet

- Jamaneurology Burke 2019 VP 190011Document2 pagesJamaneurology Burke 2019 VP 190011joao victorNo ratings yet

- Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) in Medical PracticeDocument6 pagesMild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) in Medical PracticeMCNo ratings yet

- 10.1038@s41380 019 0634 7Document16 pages10.1038@s41380 019 0634 7Steven MenaNo ratings yet

- Si OlfatorioDocument15 pagesSi OlfatorioMariana Lizeth Junco MunozNo ratings yet

- A Rare Case of Early-Onset Bipolar Affective Disorder During LockdownDocument1 pageA Rare Case of Early-Onset Bipolar Affective Disorder During LockdownRupinder GillNo ratings yet

- Frontiers Autism Spectrum Disorders: Clinical and Research: Arch. Dis. ChildDocument7 pagesFrontiers Autism Spectrum Disorders: Clinical and Research: Arch. Dis. ChildBernardita LoredoNo ratings yet

- The Course of Bipolar Disorder: A Review of Onset and PrognosisDocument11 pagesThe Course of Bipolar Disorder: A Review of Onset and Prognosis주병욱No ratings yet

- Bipolar Prodrome Meta-Analysis Examines Prevalence of Symptoms Before Initial or Recurrent Mood EpisodesDocument14 pagesBipolar Prodrome Meta-Analysis Examines Prevalence of Symptoms Before Initial or Recurrent Mood EpisodesEmiNo ratings yet

- Neuromodulation TechniquesDocument23 pagesNeuromodulation TechniquesAlexandra BuenoNo ratings yet

- PAMPHLETDocument15 pagesPAMPHLETMa. Divina Faustina MenchuNo ratings yet

- Neuropsychology and Fuctional Impact of Covid 19Document3 pagesNeuropsychology and Fuctional Impact of Covid 19Nan JimenezNo ratings yet

- Personality Disorder Across The Life CourseDocument9 pagesPersonality Disorder Across The Life CourseZackarias Quiroga AlfaroNo ratings yet

- Bipolar Lancet 2015Document12 pagesBipolar Lancet 2015Javier Alonso Jara CánovasNo ratings yet

- Prolonged Psychosocial Effects of Disaster: A Study of Buffalo CreekFrom EverandProlonged Psychosocial Effects of Disaster: A Study of Buffalo CreekRating: 1 out of 5 stars1/5 (1)

- Trastornos RBD en Atrofia de Múltiples SistemasDocument10 pagesTrastornos RBD en Atrofia de Múltiples SistemasHabib G. Moutran BarrosoNo ratings yet

- The Best Evidence For Progressive Myoclonic Epilepsy - A Pathway To Precision TherapyDocument11 pagesThe Best Evidence For Progressive Myoclonic Epilepsy - A Pathway To Precision TherapyHabib G. Moutran BarrosoNo ratings yet

- Tratamiento Farmacológico Trastornos Sueño REMDocument24 pagesTratamiento Farmacológico Trastornos Sueño REMHabib G. Moutran BarrosoNo ratings yet

- Trastornos Del Ritmo CircardianoDocument38 pagesTrastornos Del Ritmo CircardianoHabib G. Moutran BarrosoNo ratings yet

- Genetic and Therapeutic Review of Progressive Myoclonic EpilepsiesDocument10 pagesGenetic and Therapeutic Review of Progressive Myoclonic EpilepsieschintanNo ratings yet

- Neurologist Communicationg The Diagnosis of ELADocument9 pagesNeurologist Communicationg The Diagnosis of ELAHabib G. Moutran BarrosoNo ratings yet

- JCSM 6470Document43 pagesJCSM 6470Nguyen Manh HuyNo ratings yet

- Trastornos Del Sueño en AMSDocument17 pagesTrastornos Del Sueño en AMSHabib G. Moutran BarrosoNo ratings yet

- Revisión Sistemática de Melatonina en Dosis AltasDocument21 pagesRevisión Sistemática de Melatonina en Dosis AltasHabib G. Moutran BarrosoNo ratings yet

- Mann 3Document10 pagesMann 3Ahmed FakruNo ratings yet

- REM Sleep - ReviewDocument4 pagesREM Sleep - ReviewHabib G. Moutran BarrosoNo ratings yet

- Progressive Myoclonic Epilepsies - NeurologyDocument3 pagesProgressive Myoclonic Epilepsies - NeurologyHabib G. Moutran BarrosoNo ratings yet

- REM - RBD ReviewDocument8 pagesREM - RBD ReviewHabib G. Moutran BarrosoNo ratings yet

- Rapid Eye Movement Sleep Behaviour Disorder - ReviewDocument10 pagesRapid Eye Movement Sleep Behaviour Disorder - ReviewHabib G. Moutran BarrosoNo ratings yet

- Bioethical Implications of End of Life Decision Making in Patients With Dementia - A Tale of Two SocietiesDocument19 pagesBioethical Implications of End of Life Decision Making in Patients With Dementia - A Tale of Two SocietiesHabib G. Moutran BarrosoNo ratings yet

- Brain Injury After Cardiac Arrest - From Prognostication of Comatose Patients To RehabilitationDocument12 pagesBrain Injury After Cardiac Arrest - From Prognostication of Comatose Patients To RehabilitationHabib G. Moutran BarrosoNo ratings yet

- Progressive Myoclonic Epilepsies Definitive and Still Undetermined CausesDocument7 pagesProgressive Myoclonic Epilepsies Definitive and Still Undetermined CausesHabib G. Moutran BarrosoNo ratings yet

- Immune Therapy in Autoimmune Encephalitis - A Systematic ReviewDocument31 pagesImmune Therapy in Autoimmune Encephalitis - A Systematic ReviewHabib G. Moutran BarrosoNo ratings yet

- POEMS Syndrome - A Report of 14 Cases and Review of The LiteratureDocument6 pagesPOEMS Syndrome - A Report of 14 Cases and Review of The LiteratureHabib G. Moutran BarrosoNo ratings yet

- A Randomized Trial of Deep-Brain Stimulation For Parkinson's DiseaseDocument13 pagesA Randomized Trial of Deep-Brain Stimulation For Parkinson's DiseaseHabib G. Moutran BarrosoNo ratings yet

- Antibody-Mediated Autoimmune Encephalitis - A Practical ApproachDocument13 pagesAntibody-Mediated Autoimmune Encephalitis - A Practical ApproachHabib G. Moutran BarrosoNo ratings yet

- CNS Diseases and UveitisDocument25 pagesCNS Diseases and UveitisHabib G. Moutran BarrosoNo ratings yet

- Cerebral Venous Thrombosis: Review ArticleDocument6 pagesCerebral Venous Thrombosis: Review ArticlefabioNo ratings yet

- Cerebral Venous Thrombosis After Vaccination Against COVID-19 in The UKDocument10 pagesCerebral Venous Thrombosis After Vaccination Against COVID-19 in The UKHabib G. Moutran BarrosoNo ratings yet

- The Role of Diet in Multiple Sclerosis - A ReviewDocument16 pagesThe Role of Diet in Multiple Sclerosis - A ReviewHabib G. Moutran BarrosoNo ratings yet

- Multiple Sclerosis - A Review - EAN 2018Document14 pagesMultiple Sclerosis - A Review - EAN 2018Habib G. Moutran BarrosoNo ratings yet

- Low Fat Plant Based Diet in Multiple SclerosisDocument11 pagesLow Fat Plant Based Diet in Multiple SclerosisNguyen KhoaNo ratings yet

- Environmental Factors Influencing Multiple Sclerosis in Latin AmericaDocument13 pagesEnvironmental Factors Influencing Multiple Sclerosis in Latin AmericaHabib G. Moutran BarrosoNo ratings yet

- 4 Levels of Perio DZDocument2 pages4 Levels of Perio DZKIH 20162017No ratings yet

- Cghs Rates BangaloreDocument26 pagesCghs Rates Bangaloregr_viswanathNo ratings yet

- 1 PBDocument21 pages1 PBDewi Puspita SariNo ratings yet

- End users' contact and product informationDocument3 pagesEnd users' contact and product informationمحمد ہاشمNo ratings yet

- Assignment On PrionsDocument22 pagesAssignment On PrionsRinta Moon100% (2)

- Disectie AnatomieDocument908 pagesDisectie AnatomieMircea SimionNo ratings yet

- English 2 Class 03Document32 pagesEnglish 2 Class 03Bill YohanesNo ratings yet

- Laporan Ok Prof Budhi Jaya - Cory RettaDocument3 pagesLaporan Ok Prof Budhi Jaya - Cory RettaCory Monica MarpaungNo ratings yet

- ICU HandoverDocument2 pagesICU HandoverMark 'Mark Douglas' DouglasNo ratings yet

- Mental RetardationDocument11 pagesMental RetardationTherese Tee-DizonNo ratings yet

- Consultant Physician Gastroenterology Posts Clyde SectorDocument27 pagesConsultant Physician Gastroenterology Posts Clyde SectorShelley CochraneNo ratings yet

- Audit Program Ppi (Mariani, SKM, Mha)Document23 pagesAudit Program Ppi (Mariani, SKM, Mha)Dedy HartantyoNo ratings yet

- College of Nursing: Bicol University Legazpi CityDocument8 pagesCollege of Nursing: Bicol University Legazpi CityFlorence Danielle DimenNo ratings yet

- Formulation Development of Garlic Powder (Allium Sativum) For Anti-Diabetic Activity Along With Pharmaceutical EvaluationDocument5 pagesFormulation Development of Garlic Powder (Allium Sativum) For Anti-Diabetic Activity Along With Pharmaceutical EvaluationIJAR JOURNALNo ratings yet

- Pediatric PerfectionismDocument20 pagesPediatric Perfectionismapi-438212931No ratings yet

- MedAspectsBio PDFDocument633 pagesMedAspectsBio PDFDuy PhúcNo ratings yet

- SextafectaDocument2 pagesSextafectaAndres Felipe Perez SanchezNo ratings yet

- To Compare Rosuvastatin With Atorvastatin in Terms of Mean Change in LDL C in Patient With Diabetes PDFDocument7 pagesTo Compare Rosuvastatin With Atorvastatin in Terms of Mean Change in LDL C in Patient With Diabetes PDFJez RarangNo ratings yet

- Meningitis Pediatrics in Review Dic 2015Document15 pagesMeningitis Pediatrics in Review Dic 2015Edwin VargasNo ratings yet

- Resume 101: Write A Resume That Gets You NoticedDocument16 pagesResume 101: Write A Resume That Gets You Noticedgqu3No ratings yet