Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Missed Monteggia FX

Uploaded by

Eric RothOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Missed Monteggia FX

Uploaded by

Eric RothCopyright:

Available Formats

|

Missed Pediatric Monteggia Fractures

James Hubbard, MD Abstract

» Careful scrutiny of radiographs is important in the assessment of

Aakash Chauhan, MD, MBA

pediatric elbow injuries. Disruption of the radiocapitellar line and an

Ryan Fitzgerald, MD increased bow of the posterior ulnar border are sometimes subtle

signs of a Monteggia injury.

Reid Abrams, MD

Scott Mubarak, MD » An attempt at closed reduction up to 4 weeks after injury has been

cited in the literature as successfully treating some missed injuries.

Mark Sangimino, MD

» Operative reduction of chronic radial-head dislocation provides good

to excellent range of motion and functional outcome in the setting of

Investigation performed at the Division irreducible chronic radial-head dislocation.

of Hand, Upper Extremity, and

Microvascular Surgery, Department of » Ulnar osteotomy and correction of the ulnar deformity component of

Orthopaedic Surgery, University of the missed Monteggia injury are the key to indirect anatomic

California, San Diego (UCSD), San reduction of the radiocapitellar joint.

Diego, California

» Supplemental procedures aimed at increasing the stability of the

radiocapitellar joint (e.g., annular ligament reconstruction, radiocapitellar

Kirschner wire fixation, radioulnar Kirschner wire fixation) should be

directed by a thorough assessment of radiocapitellar stability following

ulnar osteotomy and correction of the ulnar deformity.

Background and Epidemiology scenario, exposing the patient to potential

F

irst described by Giovanni morbidity and increasing the complexity of

Monteggia in 1814, the epony- management for the treating surgeon as early

mous Monteggia lesion as 2 weeks after the initial injury. Morbidity

describes a fracture of the ulna is primarily associated with persistent dislo-

associated with dislocation of the radio- cation of the radioulnar and radiocapitellar

capitellar joint and disruption of the prox- joints and includes restricted elbow motion,

imal radioulnar joint1. These are rare particularly in flexion and pronation7, pro-

injuries in children, constituting ,1% of gressive valgus deformity and valgus insta-

all pediatric forearm fractures with an bility8, pain, degenerative arthritis9, and

annual incidence of ,1:100,0002. When tardy ulnar and radial nerve palsies10-12.

the Monteggia lesion is identified in the

acute setting and is treated with stable Anatomy

anatomic reduction of the ulna and radio- The elbow consists of 3 articulations: the

capitellar joint, long-term outcomes are ulnohumeral joint, the radiocapitellar

generally excellent1,3,4. However, 16% to joint, and the proximal radioulnar joint.

50% of these injuries are missed at initial The annular ligament and the quadrate

presentation, with reasons cited being ligament are the primary static stabilizers of

inadequate radiographs, subtle greenstick the proximal radioulnar joint. Other liga-

fractures of the ulna, and the complexity of mentous structures that play an ancillary

evaluating the pediatric elbow with its role in stability of the proximal radioulnar

multiple ossification centers3-6. A missed joint include the oblique cord (or Weit-

diagnosis presents a challenging clinical brecht ligament), present in 52.6% of

COPYRIGHT © 2018 BY THE Disclosure: There was no source of external funding for this study. The Disclosure of Potential

JOURNAL OF BONE AND JOINT Conflicts of Interest forms are provided with the online version of the article (http://links.lww.com/

SURGERY, INCORPORATED JBJSREV/A344).

JBJS REVIEWS 2018;6(6):e2 · http://dx.doi.org/10.2106/JBJS.RVW.17.00116 1

| Missed Pediat r ic Monteg g ia Fractures

forearms, which originates just distal to

the radial notch on the ulna and inserts TABLE I The Letts Classification for Pediatric Monteggia Injuries

and the Bado Classification for Monteggia Injuries

distal to the bicipital tuberosity on the

radius13, and the interosseous mem- Classification Description

brane originating on the radial aspect of

Letts classification

the ulna and inserting on the ulnar

Type A* Anterior radial-head dislocation and apex-anterior

aspect of the radius. These structures plastic ulnar deformation

are most taut in supination as a function Type B* Anterior radial-head dislocation and apex-anterior

of the shape of the radial head and the greenstick ulnar fracture

bow of the radius. The radial head is Type C* Anterior radial-head dislocation and complete ulnar

elliptical in axial cross-section, with the fracture

long axis of the ellipse perpendicular to Type D† Similar to Bado type II

the radial notch of the ulna in supina- Type E‡ Lateral radial-head dislocation and greenstick

tion14. This functions to maximally fracture of ulna

tension the annular ligament as well as Bado classification

the thick anterior portion of the quad- Type I* Anterior radial-head dislocation and apex anterior

rate ligament in supination. ulnar fracture

Type II† Posterior radial-head dislocation and apex posterior

Classification and Mechanism ulnar fracture

of Injury Type III‡ Lateral radial-head dislocation and apex lateral

ulnar fracture

The Bado classification of Monteggia

Type IV§ Dislocation of radial head in any direction and ulnar

fracture-dislocations is the most com- and radial-shaft fractures

monly used and describes 4 types of

ulnar fracture patterns with the associ- *Letts types A, B, and C represent Bado type-I pattern injuries with anterior dis-

ated direction of radial-head disloca- location of the radial head and increasing degrees of completeness of the ulnar

fracture. †Letts type-D injuries represent the classical Bado type-II pattern. ‡Letts

tion4 (Table I). Type-I injuries are the type-E lesions represent Bado type-III injuries with a greenstick fracture rather than

most common fracture-dislocation pat- a compete fracture of the ulna. §Bado type-IV injuries do not have a corresponding

tern seen in children, representing 75% type in the Letts classification.

of acute pediatric Monteggia injuries15.

Accordingly, type-I lesions represent

approximately 85% of pediatric Mon- falling patient and subsequently fails are resultant of a hyperpronation

teggia lesions in case series describing anteriorly in tension with the fracture mechanism4.

chronic missed injuries7,9,11,12,16-35. propagating in shear, resulting in the Letts et al. subsequently adapted the

Predictably, the mechanism of classical apex-anterior short-oblique Bado classification with a system more

injury varies with the direction of frac- fracture of the ulna seen in Bado type-I specific to pediatric injuries, describing 5

ture and dislocation. There are several injuries. Type-II injuries are proposed fracture patterns, types A to E37 (Table I).

proposed mechanisms by which type-I to be the result of a fall onto an out- Importantly, their classification recog-

lesions are produced, with the most stretched hand with the elbow in nizes the tendency of pediatric long bone

accepted being the hyperextension approximately 60° of flexion. This injuries to result in plastic deformation

theory proposed by Tompkins36. He results in longitudinal loading of the rather than complete fracture as seen in

proposed that type-I injuries likely forearm parallel to the long axis of the the adult population and identifies radial-

result from a patient falling with for- radius and ulna, and subsequent pos- head dislocation in the absence of a

ward momentum onto an outstretched terior dislocation of the elbow or, if the complete ulnar fracture as representing a

arm resulting in hyperextension of the ulna is weaker than the surrounding Monteggia equivalent. It has subse-

elbow. This hyperextension produces capsuloligamentous structures, a Bado quently been recognized that a truly iso-

reflexive contracture of the biceps bra- type-II injury15. Type-III injuries are lated traumatic radial-head dislocation is

chii, resulting in anterior dislocation of thought to result from a forced varus likely an exceedingly rare injury and that,

the radial head. The radius normally stress resulting in failure of the proximal on close inspection, one can usually

bears 80% of the load transmitted part of the ulna in varus and lateral or identify an ulnar injury in even the most

through the carpus to the forearm, and anterolateral dislocation of the radial subtle cases38.

when the radial head dislocates, the head15. Type-IV injuries have little

ulna becomes the primary load-bearing description of mechanism of injury in Natural History

structure in the forearm. The ulna is not the literature; however, in Bado’s initial The natural history of Monteggia injuries

equipped to bear the full weight of the description, he hypothesized that they is largely secondary to chronic radial-head

2 JUNE 2018 · VOLUME 6, ISSUE 6 · e2

Missed Pediatr ic Monteg gia Fractures |

dislocation, as the ulnar component of the may present as early as 3 months after Diagnosis

fracture will commonly heal and remodel radial-head dislocation39. Patients may present with a history of

as the child ages. With the initial disloca- With the loss of the radiocapitellar remote elbow injury, persistent pain,

tion of the radial head, the annular liga- articulation, the elbow loses approxi- decreased elbow motion, limited func-

ment and associated anterior capsular mately 33% of its valgus stability42, and tion, a fullness in the antecubital

structures fall posterior to the radial patients demonstrate instability and an space26, and, rarely, progressive cubitus

head and into the radiocapitellar joint, increase in the valgus carrying angle of the valgus deformity. An examination of the

calcifying over time and providing a elbow39. This has been reported to con- full range of motion at the elbow

block to anatomic reduction39,40. With tribute to late ulnar nerve palsy in rare including flexion, extension, pronation,

longer durations of radial-head dislo- cases43. Tardy median and posterior and supination should be undertaken as

cation, the radial head, capitellum, and interosseous nerve palsies have also been these patients often present with limited

radial notch of the ulna have been noted described secondary to tenting of the range of motion15. A full distal neuro-

to undergo dysplastic changes3,39-41. nerve over the dislocated radial head10,43. vascular examination should also be

The dislocated radial head hypertro- The loss of the normal anatomic rela- performed as posterior interosseous,

phies and the normally concave artic- tionships of the radiocapitellar joint and anterior interosseous, and ulnar nerve

ular surface becomes convex. The proximal radioulnar joint results in the palsies have been reported in cases of

capitellum is also reported to lose its loss of normal range of motion, the chronic radial-head dislocation10,43.

normal contour, demonstrating a flat- development of contractures, and Standard orthogonal radiographs

tened appearance39,40. Kim et al. dem- abnormal loading of these joints, ulti- of the injured elbow should be obtained

onstrated that these dysplastic changes mately resulting in late osteoarthritis9,12. and inspected for radiocapitellar joint

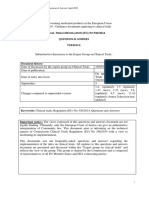

Fig. 1

Figs. 1-A through 1-D Missed Monteggia injury. (Reproduced, with permission, from San Diego Pediatric Orthopedics [SD PedsOrtho].) A 9-year-old,

right-hand-dominant boy fell onto the outstretched left forearm while skateboarding. He was evaluated by an outside facility where he was treated in a long

arm cast for elbow pain for 6 weeks. The long arm cast was discontinued afterwards, and the patient continued to report elbow stiffness and limited motion.

He was treated with activity modifications and physical therapy with no improvement. Fig. 1-A He was then eventually evaluated by another outside

orthopaedic surgeon who recognized a missed Monteggia injury 11 months after the initial injury on a lateral radiograph. Fig. 1-B The patient was then

referred for pediatric orthopaedic surgery evaluation and was evaluated 12 months after the initial injury, again with the radiograph demonstrating an

anterior radial-head dislocation consistent with a missed Monteggia injury. Figs. 1-C and 1-D Full-length lateral radiographs of the bilateral forearms

demonstrate a positive ulnar bow sign (denoted by an asterisk) of the left proximal part of the ulna (Fig. 1-C) compared with the right side (Fig. 1-D). As seen

in Figures 1-A and 1-B, the anterior radial-head dislocation is clearly noted on initial and follow-up injury radiographs as the radiocapitellar line is not colinear.

JUNE 2018 · VOLUME 6, ISSUE 6 · e2 3

| Missed Pediat r ic Monteg g ia Fractures

congruity. Images should be scrutinized should be ,2 to 3 mm in the uninjured no treatment in the setting of radial-head

by a practitioner with experience in ulna, and that deviation greater than this in dislocations that have been present for

reading pediatric elbow radiographs. the setting of radial-head dislocation rep- .3 months as he believed that the

The complexity of the pediatric elbow resented a likely traumatic etiology and postoperative loss of elbow function was

with its numerous ossification centers mild Monteggia equivalent injury38. a greater hindrance than the instability

has been cited as a potential reason for Radiographs of the contralateral forearm associated with a chronically dislocated

why Monteggia injuries are not diag- provide a useful comparison in attempting radial head47. It has since been noted

nosed in the acute setting among emer- to identify subtle injuries and should also that, with increasing functional

gency room physicians and junior be obtained. demands on the elbow as patients age,

orthopaedic residents6. Given the vari- patients can be expected to experience

able radiographic appearance of the Treatment increasing pain, deformity, and unsat-

pediatric elbow depending on the Treatment of the pediatric Monteggia isfactory range of motion39.

patient’s age, images of the contralateral injury is ideally performed in the acute

elbow may be useful in children ,10 setting. The preferred method of treat- Operative Treatment

years of age as a reference for the child’s ment in the acute setting is closed Operative treatment of missed Mon-

normal anatomy. Radiocapitellar joint reduction and long arm casting in supi- teggia lesions has been undertaken in

congruity is assessed on a true lateral nation with a focus on anatomic ulnar cases in which the radiocapitellar joint

radiograph of the elbow (Figs. 1-A and reduction guiding reduction of the ra- cannot be maintained in a reduced state

1-B). A line called the radiocapitellar line diocapitellar joint. As early as 2 weeks by closed means. Specific indications

or, eponymously, the Storen line is after injury, attempts at closed reduction include loss of function, progressive

drawn from the center of the radial neck, may be met with failure11. However, in deformity, decreased range of motion,

through the radial head and capitel- the subacute setting, for patients pre- and increased pain in the affected

lum44. If the radiocapitellar joint is senting up to 4 weeks after their initial elbow24,30,48-50. Several authors have

congruent, the radiocapitellar line injury, closed reduction may be suc- suggested operative intervention as soon

should bisect the capitellum in all cessful in maintaining stable reduction as the missed lesion has been identified,

degrees of flexion and extension of the of the radiocapitellar joint7. No defini- as the duration of neglect has corre-

elbow15. Elbow radiographs should also tive interval from initial injury to treat- sponded with worse outcomes23,39.

be assessed for radial-head hypertrophy ment has been established beyond which Contraindications to operative reduc-

with loss of its convex articular surface, an attempt at closed reduction has been tion have been described on the basis of

as well as dysplastic flattening of the deemed futile; however, most authors the duration of radial-head dislocation

capitellar articular surface. Radial-head describe a .4-week delay in treatment and patient age at the time of surgical

hypertrophy is assessed via the head- as representing a chronic Monteggia intervention. The most commonly cited

neck ratio on a lateral radiograph of the lesion that is no longer amenable to criteria for surgical intervention are a

elbow. The diameter of the radial head is closed reduction21,27,28,33,45,46. Opera- duration of radial-head dislocation of

measured at the widest portion of the tive treatment has become the gold ,3 years and patient age of ,12

metaphysis adjacent to the physis, and standard for the management of these years12,51. Nakamura et al. evaluated 22

the diameter of the radial neck is mea- injuries; myriad techniques and opin- patients undergoing open reduction of

sured at the narrowest portion of the ions exist in the current literature with the radial head with ulnar correction

neck, just proximal to the bicipital regard to how to best approach the osteotomy and annular ligament recon-

tuberosity. Radial-head hypertrophy is chronic missed Monteggia injury. We struction with a mean follow-up of 7

present if the head-neck ratio is .1.539. provide a review of this literature below. years. Interestingly, those patients who

Radiographs of the forearm should were $12 years old at the time of the

be obtained to assess for plastic deformity Nonoperative Treatment surgical procedure and also had a delay of

of the ulna. On a true lateral radiograph of Recent literature has described a limited treatment of $3 years had an 88% rate

the elbow, the posterior border of the ulnar role for nonoperative management in of radial-head subluxation or osteoar-

diaphysis should be a straight line. In Lin- the setting of chronic Monteggia lesions. thritic changes12. Conversely, reduction

coln and Mubarak’s method (the ulnar A review of the literature provides his- of the radial head was maintained, and

bow sign), they drew a line tangential to the torical context for the evolution of and osteoarthritic changes were absent at the

posterior border of the ulna in both healthy rationale for modern surgical manage- time of the final follow-up in all patients

controls and patients with known radial- ment. There is often a delay in the pre- who were within ,3 years of the injury

head dislocation (Figs. 1-C and 1-D). They sentation of symptoms, which or who were ,12 years of age at the time

then measured the maximum perpendic- previously led some authors to believe of the surgical procedure12.

ular distance of this line from the ulnar that chronic radial-head dislocation was In further support of these criteria,

shaft and determined that this distance largely asymptomatic. Blount advised radial-head dislocation of $3 years has

4 JUNE 2018 · VOLUME 6, ISSUE 6 · e2

Missed Pediatr ic Monteg gia Fractures |

been shown to predict more pro- dislocated radius, and annular ligament wire and allowed active range of motion.

nounced dysplastic changes of the radial reconstruction using a turned-down In their series of 8 patients, 7 underwent

head52. However, in the absence of central slip of triceps tendon passed cir- radiocapitellar pinning, and the

dysplastic changes, several authors have cumferentially around the neck of the 1 patient who underwent annular liga-

demonstrated good results following radius and inserted into a drill-hole in ment reconstruction without pinning

reduction up to 10 years after the initial the lateral part of the ulna. Patients were demonstrated residual radial-head sub-

injury7,21,30,33,45,53. Horii et al. dem- subsequently splinted in full extension luxation at the 7-year follow-up.

onstrated that it was possible to obtain and supination for 6 weeks, with active Therefore, the authors concluded

good reduction in patients 18 to 20 years range of motion as tolerated to follow. In that radiocapitellar pinning was neces-

of age; however, they noted that the his original series of 6 patients, he sary to maintain reduction. This

interval from the time of the injury to the described good results using this proce- became a popular modification as

time of the surgical procedure was 2 to 7 dure, with the exception of 1 recurrent authors believed that transarticular

months in these patients. They con- dislocation in a patient in whom the immobilization of the radiocapitellar

cluded that the radial head can be suc- triceps tendon was of poor quality for joint maintained reduction and

cessfully reduced regardless of age if reconstruction54. Many authors have protected the healing annular ligament

treated within a year after the initial advocated for annular ligament recon- reconstruction3,29. Letts et al. further

injury51. Thus, it might be suggested struction as a necessary component of modified this technique, advocating

that these numbers be used as guidelines surgical treatment of missed Monteggia against the transradiocapitellar pin over

rather than strict criteria and that all lesions3,5,21,29,37,40,54,55; however, the concern for intra-articular pin breakage,

patients should be carefully evaluated for methods of reconstruction have varied, and recommending pinning the proxi-

dysplastic changes to the radial head with authors describing procedures uti- mal part of the radius to the ulna37.

prior to attempted surgical reduction of lizing a slip of triceps tendon5,21,29,40,54, Radiocapitellar pinning remains con-

the radiocapitellar joint. a free fascial loop3,55, a free palmaris troversial, with authors reporting good

Many surgical techniques have tendon loop40, and a slip of forearm outcomes both with and without trans-

been developed to address this complex fascia37. Seel and Peterson recognized fixing the capitellum and radial head.

clinical problem, yet there remains no that the original Bell Tawse procedure However, this strategy provides an

consensus gold-standard treatment at and many of its described variations option for increasing stability of the

this time. Further, treatment of these produced a posterolaterally directed reduced radiocapitellar joint in particu-

injuries can vary in difficulty depending reducing force on the radial head. larly unstable dislocations9,23,31.

on the chronicity of the injury and may Although they noted that this may be

necessitate adjunct procedures to assist appropriate for anteromedial disloca- Ulnar Osteotomy

in maintaining reduction of the radio- tions, it may malreduce other injuries Lloyd-Roberts and Bucknill recognized

capitellar joint. Broadly, treatment (e.g., anterolateral, lateral, and posterior early in the evolution of the treatment of

strategies have aimed to reduce the radial-head dislocations). To address missed Monteggia lesions that, despite

radial-head dislocation through recon- this, they developed a 2-drill-hole adequate debridement of interposed

struction of the ligamentous stabilizers annular ligament reconstruction tech- capsuloligamentous tissue from the ra-

of the radiocapitellar joint and/or via nique that allows the reconstructed diocapitellar joint, some radial-head

correction of the associated ulnar annular ligament to function in its ana- dislocations required ulnar osteotomy to

deformity. Therefore, orthopaedic sur- tomic role as a U-bolt, producing a more achieve full reduction40. Kalamchi was

geons treating these patients should be centrally directed reducing force33. All the first to discuss ulnar osteotomy as a

aware of the reconstructive options options appear to function similarly, primary means for obtaining radial-head

available for addressing the radial-head with authors reporting good results in all reduction in the English-language liter-

dislocation and have a guided strategy to case series regardless of the chosen ature. He recognized that residual ulnar

address the ulnar deformity. reconstructive method. deformity may splint the radial head in

an unreduced position via the interos-

Annular Ligament Reconstruction Radiocapitellar Pinning seous membrane and that subsequent

(without Osteotomy) Lloyd-Roberts and Bucknill modified correction of the ulnar deformity would

Open treatment of chronically dis- the Bell Tawse procedure by securing allow for reduction of the radial head. In

located Monteggia lesions was first their radiocapitellar joint reduction with his study of 2 patients, he performed an

described by Bell Tawse in 196554. His a Kirschner wire passed through the ulnar osteotomy through a 1-cm inci-

procedure entailed a posterolateral capitellum and proximal part of the sion using multiple passes of a Kirschner

approach to the elbow with excision of radius with the elbow in flexion40. They wire to maintain the structural integrity

interposed capsular material from the subsequently splinted patients for 6 of the surrounding periosteum. He then

radiocapitellar joint, reduction of the weeks, at which point they removed the performed open reduction of the radial

JUNE 2018 · VOLUME 6, ISSUE 6 · e2 5

| Missed Pediat r ic Monteg g ia Fractures

Fig. 2

Figs. 2-A through 2-D Annular ligament button-hole and proximal ulnar osteotomy through the Kocher approach. (Reproduced, with permission,

from San Diego Pediatric Orthopedics [SD PedsOrtho].) Fig. 2-A Intraoperative image highlighting an intact annular ligament under the Freer Elevator

(Sklar) (black arrow), which demonstrates a button-hole phenomenon. The radial head was dislocated anteriorly and medial to the annular ligament. The

annular ligament was vented to facilitate reduction of the radial head. However, given the chronicity of the injury, the annular ligament was taken down

and was repaired at the end of the case. Figs. 2-B, 2-C, and 2-D Intraoperative images, highlighting the exposure of the proximal part of the ulna (Fig. 2-B)

followed by a crescentic osteotomy (white arrow) of the proximal part of the ulna (Fig. 2-C), and a corresponding radiographic image with the white arrow

highlighting the ulnar osteotomy site (Fig. 2-D).

head with slight overcorrection of the both the proximal part of the ulna and required a mean time of 3.5 months in the

ulnar deformity, repairing the remnant the radiocapitellar joint through a single external fixator frame. They obtained

annular ligament around the proximal incision. excellent clinical outcomes in all 4

part of the radius. Both patients dem- Methods for concentric reduction patients in their series. However, the

onstrated maintenance of the radio- of the radiocapitellar joint vary. Some most commonly employed technique for

capitellar joint reduction at the 1-year authors have contended that open radiocapitellar joint reduction is open

follow-up and good range of motion at reduction of the radial head is reduction, with many authors finding it

the 5-year follow-up56. unnecessary16,18,19,22,24. Lädermann necessary to excise interposed capsu-

Numerous case series have subse- et al. obtained closed reduction of the loligamentous tissue to obtain concentric

quently reported on ulnar osteotomy in radiocapitellar joint via ulnar osteotomy reduction of the radiocapitellar

the treatment of missed Monteggia with lengthening and correction of the joint7,9,12,20,21,23,25,27,28,30-32,53,56.

lesions, and surgical techniques have ulnar angular deformity through the Opinions on the necessity and

varied to some degree between nearly osteotomy site in 6 patients. All patients method of stabilizing the reduced radial

every case series. This is largely attrib- demonstrated normal range of motion head vary among authors who agree that

utable to the rarity of this injury. and had excellent clinical outcomes open reduction of the radiocapitellar

Described approaches include a postoperatively16. Bor et al. described joint is required. Some authors have

single-incision technique9,12,16,18,19,21- closed reduction of the radiocapitellar contended that the ulnar osteotomy

25,28,30-32,53

and a dual-incision joint using an Ilizarov technique to facilitates stability of the radial-head

technique 20,24,56. Most authors gradually lengthen and correct the reduction through the interosseous

have advocated a single-incision angular deformity of the ulna through membrane and advocate against extensive

technique through either a Boyd the ulnar osteotomy site via callotasis19. annular ligament reconstruction23,27,31,53,

approach9,21,23,26,27,57 or a Kocher They obtained serial radiographs at the and others have advocated for repair20,23,56

approach11,16,24 (Figs. 2-A through clinical follow-up, adjusting the angle or reconstruction7,12,18,21,27,28,30,32 of

2-D). These approaches are favored and distraction through the osteotomy the annular ligament to increase the sta-

because they afford the surgeon the as necessary to obtain concentric radio- bility of the joint. Described options for

ability to perform procedures directed at capitellar joint reduction. Reduction annular ligament reconstruction include

6 JUNE 2018 · VOLUME 6, ISSUE 6 · e2

Missed Pediatr ic Monteg gia Fractures |

techniques utilizing triceps tendon or that even with osteotomy and anatomic

fascia7,9,11,17,21,30,32,34, forearm extensor correction of the ulna, excess scar tissue or

fascia12,25-28, free palmaris longus ten- callus at the fracture site may act as a ful-

don12, and absorbable suture18. Delpont crum to the radius during pronation and

et al. provided the only direct comparison that this may be a cause for recurrent

of ulnar osteotomy with annular ligament anterior radial-head dislocation, or, in the

reconstruction to ulnar osteotomy with- setting of a firmly stabilized radial head

out annular ligament reconstruction9. In (e.g., following annular ligament recon-

this multicenter study, the surgeon’s struction), this may result in a mechanical

standard practice dictated if annular lig- block to pronation. Further, they recom-

ament reconstruction was undertaken. mended overcorrection at the ulnar

They reviewed 28 cases in which all osteotomy as this further tensions the

patients underwent overcorrection oste- interosseous membrane against forces that

otomy, with 12 patients undergoing would lead to recurrent radial-head dis-

annular ligament reconstruction in asso- location32. All case series from the last

ciation with open reduction of the ra- decade recommend a protocol of ulnar

diocapitellar joint, and 16 patients osteotomy with the degree of angular

undergoing open reduction of the radio- correction through the osteotomy to be

capitellar joint alone. They showed no determined by the position that allows for

significant difference in clinical func- a stable reduction of the radial head in all Fig. 3

tional outcomes between groups. Annu- combinations of flexion, extension, pro- Figs. 3-A and 3-B Reduction of the radial

lar ligament reconstruction did not nation, and supination. Invariably, these head and ulnar osteotomy fixation. (Re-

produced, with permission, from San Diego

guarantee radial-head stability, with 2 studies demonstrate overcorrection of the Pediatric Orthopedics [SD PedsOrtho].)

patients in the annular ligament recon- ulnar deformity9,12,16,19,23,27,31. Anteroposterior (Fig. 3-A) and lateral

struction group demonstrating recur- The location of ulnar osteotomy (Fig. 3-B) radiographs demonstrating

reduction of the radial head after proximal

rence of dislocation. They concluded that has been described at the center of ulnar osteotomy and subsequent fixation

annular ligament reconstruction is not rotation of angulation (CORA; often using a 2.7-mm limited contact

beneficial in conjunction with ulnar diaphyseal)16,26,28,30,32,56, and at the prox- dynamic compression plate bent with

apex-dorsal angulation to correct the ulnar

osteotomy in chronic Monteggia lesions imal part of the metaphysis9,12,16,17,19,21-27. deformity.

and that, although ulnar osteotomy with Lädermann et al. performed osteotomies

or without annular ligament reconstruc- at both the CORA and the proximal part Fixation constructs for the ulnar

tion consistently produced functional of the metaphysis16. One patient who osteotomy have varied from reports of

improvement in the setting of Bado type-I underwent osteotomy at the CORA no fixation at all56, relying on the peri-

lesions, it may be less effective in treat- went on to nonunion requiring revision osteum for stability, to fixation with an

ment of Bado type-III lesions. and bone-grafting. The authors con- elastic nail16, Kirschner wire7,11,23,28,32,33,

The degree of angular correction cluded that proximal osteotomy is a better plate and screws9,11,12,16,17,20,21,23,25-

27,30,32,34,53

through the ulnar osteotomy has been option because of the better metaphyseal , and, more recently, external

described as corrective (i.e., restoration blood supply precluding an increased risk fixation18,19,22,24,27,31. Proponents of

of the posterior cortical line)28,32, over- of nonunion, and the shorter proximal leaving the osteotomy unfixed have

corrective (i.e., reversing the original bone segment allowing for finer adjust- argued that this approach allows for natural

deformity)16,21,22,27,32,53,56, and ment of the ulnar angulation. Horii et al. remodeling of the ulna over time58. How-

allowing for stable radial-head reduc- additionally recommended that more ever, this approach necessitates prolonged

tion to guide the degree of angular proximal osteotomy also maintains the immobilization, which has been cited as a

correction9,12,19,23,24,30,31. Inoue and stouter distal fibers of the interosseous cause for elbow contracture and limited

Shionoya performed the only retro- membrane intact to the distal portion of range of motion following radial-head

spective review directly comparing the ulna, better translating ulnar correc- reduction8,34,46. Kirschner wire and elastic

patients undergoing corrective ulnar tion to the intact radius51. None of the nail fixation provide more stability than

osteotomy with patients undergoing literature is sufficient to demonstrate an periosteum alone; these constructs only

overcorrection ulnar osteotomy in the effect on union rate and maintenance of provide relative stability, which may be

treatment of Bado type-I injuries. They radial-head reduction; however, the most inadequate for maintenance of angular

demonstrated a significant increase (p # obvious benefit of an ulnar metaphyseal correction of the ulna, leading to recurrent

0.01) in patient functional outcomes in osteotomy is that the radiocapitellar joint radial-head dislocation51. Rigid fixation of

the overcorrection group, particularly in may be addressed directly through the the osteotomy site with a plate-and-screw

pronosupination. They hypothesized same incision. construct provides absolute stability

JUNE 2018 · VOLUME 6, ISSUE 6 · e2 7

| Missed Pediat r ic Monteg g ia Fractures

TABLE II Demographic Data of Outcome Studies for Missed Pediatric Monteggia Fractures*

No. of Age at Time of Interval from Injury

Study Patients Sex† Surgery‡ (yr) to Treatment‡ Bado Classification†

54

Bell Tawse (1965) 7 M (2), F (5) 7.1 (4.5 to 10) 14.1 mo (1 to 34 mo) I (7)

Lloyd-Roberts40 (1977) 8 NR 5.5 (3 to 8) 17.8 mo (4 to 36 mo) I (5), II (1),

uncategorized radial-

head dislocation (2)

Hurst29 (1983) 1 M (1) 12 2 yr I (1)

Fowles3 (1983) 5 M (2), F (3) 7.2 (3 to 9) 9.1 mo (1.5 to 24 mo) I (5)

Kalamchi56 (1986) 2 F (2) 5 (2.5 to 7.5) 5 mo (3.5 to 6.5 mo) I (2)

Hirayama53 (1987) 9 M (5), F (4) NR (2 to 12) NR (2 to 36 mo) I (5), III (4)

21

Stoll (1992) 8 NR 8.5 (4.3 to 15.5) 3.3 yr (1 to 9.5 yr) I (6), II (1), unknown (1)

Oner49 (1993) 7 M (1), F (6) 5.7 (4 to 9) 8.75 mo (1.25 to 16 mo) I (5), III (2)

Best30 (1994) 6 NR 9.8 (2.75 to 12) 27.4 mo (7 to 67 mo) I (6)

Tajima20 (1995) 23 NR NR NR I (10), II (2), III (9), IV (2)

Rodgers11 (1996) 7 M (3), F (4) 6.75 (1 to 12) 13.7 mo (1 to 39 mo) I (6), IV (1)

Devnani46 (1997) 3 M (2), F (1) 4.4 (2 to 5.66) 7.33 wk (6 to 8 wk) I (3)

Cappellino34 (1998) 3 F (3) 4 (1.4 to 6) 10 wk (NR) I (3)

Inoue32 (1998) 12 M (7), F (5) 7 (3 to 11) 16 mo (2 to 60 mo) I (12)

Seel33 (1999) 7 F (7) 5.8 (3.25 to 9) 30 mo (3 to 84 mo) NR

De Boeck35 (2000) 4 M (3), F (1) 7.1 (4 to 8.5) 10.5 mo (5 to 21 mo) I (4)

Exner22 (2001) 2 M (1), F (1) 7.13 (2.25 to 12) 2.6 yr (0.25 to 5 yr) I (2)

Horii51 (2002) 22 M (9), F (13) 10.1 (4 to 20) 10 mo (2 to 62 mo) NR

Kim39 (2002) 12 NR 7.4 (3 to 11) 30.3 mo (3 to 144 mo) I (11), II (1)

25

Degreef (2004) 6 M (4), F (2) 5 (2 to 6) 17 wk (5 to 59 wk) I (6)

David-West7 (2005) 8 M (5), F (3) 6.3 (4 to 8) 33.5 wk (2 to 192 wk) I (8)

Hasler24 (2005) 15 M (6), F (9) 9.5 (5 to 15) 22 mo (2 to 84 mo) I (15)

Hui28 (2005) 15 M (10), F (5) 8.25 (3 to 16) 3 mo (1.5 to 24 mo) I (14), III (1)

Koslowsky18 (2006) 3 F (3) 6.33 (6 to 7) 4 mo (1 to 7 mo) I (1), II (1), IV (1)

Wang26 (2006) 13 M (11), F (2) 8.3 (4 to 13) 7.8 yr (1 to 16.9 yr) I (13)

Belangero59 (2007) 8 M (2), F (6) 5.2 (2.7 to 10) 9.5 mo (1 to 18 mo) I (8)

Lädermann16 (2007) 6 M (3), F (3) 6.5 (4 to 8) 17 mo (1 to 49 mo) I (5), II (1)

Nakamura12 (2009) 22 M (14), F (8) 10 (4 to 16) NR I (19), III (1), IV (2)

23

Rahbek (2011) 16 M (11), F (5) 7.5 (3 to 13) 21 mo (1 to 83 mo) I (16)

Stitgen17 (2012) 1 M (1) 2.66 7 yr I (1)

Song27 (2012) 10 M (8), F (2) 7.5 (6 to 10) 1.7 yr (0.1 to 5 yr) I (6), III (4)

Lu31 (2013) 33 M (23), F (10) 7 (3 to 13) 15 mo (1.5 to 84 mo) NR

9

Delpont (2014) 28 M (12), F (16) 7 (4 to 12) 9.5 mo (3 to 44 mo) I (25), III (3)

Bor19 (2015) 4 M (2), F (2) 9.75 (9 to 11) 24 mo (3 to 54 mo) I (4)

*NR 5 not reported. †The number of patients is given in parentheses. ‡The values are given as the mean, with or without the range in parentheses.

allowing for early postoperative range of data in the literature with regard to the treatment or longer12,23,26,27. Across

motion, minimizing contracture51 (Figs. surgical treatment of chronic Monteggia these 4 studies, the majority of patients

3-A and 3-B). lesions, and comparisons across studies achieved good to excellent outcomes,

are made difficult by heterogeneity in with a mean redislocation rate of 6.6%.

Outcomes outcome measures. Most case series have Nakamura et al. reported on long-

Tables II, III, and IV show a thorough provided only short-term outcome data, term outcomes of open reduction of

summary of the literature and outcomes. with only 4 case series reporting final the radial head in combination with

There is a paucity of long-term outcome results at a mean time of 7 years after posterior-bending elongation ulnar

8 JUNE 2018 · VOLUME 6, ISSUE 6 · e2

Missed Pediatr ic Monteg gia Fractures |

TABLE III Surgical Information for Outcome Studies for Missed Pediatric Monteggia Fractures*

Approach for Ulnar Type of Ulnar Annular Ligament

Radial-Head Osteotomy Osteotomy Transradiocapitellar Reconstruction

Study Operative Treatment† Reduction Site† Fixation† Wire† Graft†

54

Bell Tawse Open reduction of radial head and Boyd NA NA No Triceps (6)

(1965) annular ligament reconstruction (6);

attempted closed reduction (1)

Lloyd- Open reduction of radial head and Boyd NA Plate and screws Yes (7) Palmaris (2),

Roberts40 annular ligament reconstruction (5); (1) triceps (6)

(1977) ulnar osteotomy, open reduction of

radial head, and annular ligament

reconstruction (1)

Hurst29 (1983) Open reduction of radial head and Boyd None NA Yes (6) Triceps (1)

annular ligament reconstruction (1)

Fowles3 (1983) Ulnar osteotomy (1); ulnar NR NR Plate and screws Yes (5) Remnant annular

osteotomy and annular ligament (2) ligament (4)

reconstruction (1); annular ligament

reconstruction (3)

Kalamchi56 Ulnar osteotomy and annular Kocher Site of original Molded cast (no No Remnant annular

(1986) ligament reconstruction (2) fracture (2) internal fixation) ligament (2)

Hirayama53 Ulnar osteotomy (9) Boyd Proximal part of Plate and screws No NA

(1987) metaphysis (9) (9)

Stoll21 (1992) Closed reduction (1); open Boyd Proximal part of Plate and screws Yes (3) Triceps tendon (5)

reduction of radial head, ulnar metaphysis (5) (5)

osteotomy, radial osteotomy, and

late radial-head excision (1); open

reduction of radial head and

annular ligament reconstruction (1);

radial-head excision (1); open

reduction of radial head, ulnar

osteotomy, and annular ligament

reconstruction (4)

Oner49 (1993) Open reduction of radial head and Boyd NA NA Yes (7) Triceps tendon (7)

annular ligament reconstruction (7)

Best30 (1994) Ulnar osteotomy and open Kocher CORA (7) None (5), plate Yes (7) Triceps tendon

reduction of radial head (1); ulnar and screws (2) (5), remnant

osteotomy, open reduction of radial annular ligament

head, and annular ligament (1)

reconstruction (6; note: 1 repeat

operation for late loss of reduction)

Tajima20 (1995) Isolated ulnar osteotomy (13); NR NR NR No NA

isolated radial shaft osteotomy (3);

combined radial and ulnar

osteotomies (2); radial-head

resection (5)

Rodgers11 Closed reduction of radial head and Kocher NR Kirschner wire (1), Yes (1) Triceps, ulnar

(1996) ulnar osteotomy (1); open reduction plate and screws periosteum,

of radial head and annular ligament (2), Rush rod (1), repair

reconstruction (2); open reduction and none (1)

of radial head, annular ligament

reconstruction, and ulnar

osteotomy (4)

Devnani46 Ulnar osteotomy and open Anterolateral Site of original 1.6-mm Kirschner Yes (3) NA

(1997) reduction of radial head (2); open fracture (2) wire

reduction of radial head (1)

Cappellino34 Open reduction of radial head and Boyd NR Plate and screws Yes (2) Triceps (3)

(1998) annular ligament reconstruction (2); (1)

open reduction of radial head,

annular ligament reconstruction,

ulnar osteotomy (1)

Inoue32 (1998) Ulnar osteotomy and open Posterolateral CORA (12) Plate and screws Yes (8) Triceps fascia (4)

reduction of radial head (8); ulnar (NR); Kirschner

osteotomy, open reduction of radial wires (NR);

head, annular ligament combination plate

reconstruction (4) and screws or

Kirschnerwires(NR)

continued

JUNE 2018 · VOLUME 6, ISSUE 6 · e2 9

| Missed Pediat r ic Monteg g ia Fractures

TABLE III (continued )

Approach for Ulnar Type of Ulnar Annular Ligament

Radial-Head Osteotomy Osteotomy Transradiocapitellar Reconstruction

Study Operative Treatment† Reduction Site† Fixation† Wire† Graft†

33

Seel (1999) Open reduction of radial head, Kocher NR Steinmann pin (1) Yes (4) Remnant annular

annular ligament reconstruction, ligament (5),

ulnar osteotomy (1); open reduction triceps (2)

of radial head and annular ligament

reconstruction (6)

De Boeck35 Open reduction of radial head Kocher NA NA Yes (4) NA

(2000)

Exner22 (2001) Ulnar osteotomy and external NA Proximal part of External fixation No NA

fixation (2) metaphysis (2) (2)

Horii51 (2002) Ulnar osteotomy (10); ulnar Kocher Proximal part of Plate and screws No Triceps fascia (11)

osteotomy and annular ligament metaphysis (NR);

reconstruction (6); ulnar osteotomy, (NR), ulnar shaft intramedullary

radial osteotomy, and annular (NR) Kirschner wire

ligament reconstruction (2); annular (NR)

ligament reconstruction (3); and

radial osteotomy (1)

Kim39 (2002) Open reduction of radial head and Posterior CORA (6) Plate and screws Yes (4) Triceps (11)

annular ligament reconstruction (2); (6)

ulnar osteotomy, open reduction of

radial head, and annular ligament

reconstruction (6); ulnar osteotomy,

radial shortening osteotomy, open

reduction of radial head, and

annular ligament reconstruction (1);

open reduction of radial head,

annular ligament reconstruction,

radial osteotomy, radial-head

arthroplasty, proximal radioulnar

joint notchplasty (2); open

reduction of radial head, annular

ligament reconstruction, radial

osteotomy (1)

Degreef25 Ulnar osteotomy and open Kaplan Proximal part of Plate and screws Yes (6) Forearm fascia (1),

(2004) reduction of radial head (4); ulnar metaphysis (6) (6) remnant annular

osteotomy, open reduction of radial ligament (1)

head, annular ligament

reconstruction (2)

David-West7 Ulnar osteotomy, open reduction of Boyd NR Intramedullary Yes (6) Triceps (6)

(2005) radial head, annular ligament Kirschner wire (6)

reconstruction (6); and closed

reduction (2)

Hasler24 (2005) Ulnar osteotomy, open reduction of Kocher Proximal part of External fixation No NA

radial head, and external fixation metaphysis (15) (15)

(NR); ulnar osteotomy, closed

reduction of radial head, and

external fixation (NR)

Hui28 (2005) Ulnar osteotomy, open reduction Modified Boyd Diaphyseal (12) Kirschner wires No Forearm fascia

of radial head, annular ligament (12) (15)

reconstruction (11); open

reduction of radial head and

annular ligament reconstruction

(3); ulnar osteotomy, radial

osteotomy, open reduction of

radial head, annular ligament

reconstruction (1)

Koslowsky18 Ulnar osteotomy, closed reduction NR NR External fixation Yes (1) Absorbable

(2006) of radial head, and external fixation (3) suture (2)

(1); ulnar osteotomy, open

reduction of radial head, annular

ligament reconstruction, and

external fixation (2)

Wang26 (2006) Ulnar osteotomy, open reduction of Boyd CORA (11), Plate and screws No Forearm fascia

radial head, annular ligament proximal part of (13) (13)

reconstruction (13) metaphysis (2)

continued

10 JUNE 2018 · VOLUME 6, ISSUE 6 · e2

Missed Pediatr ic Monteg gia Fractures |

TABLE III (continued )

Approach for Ulnar Type of Ulnar Annular Ligament

Radial-Head Osteotomy Osteotomy Transradiocapitellar Reconstruction

Study Operative Treatment† Reduction Site† Fixation† Wire† Graft†

59

Belangero Ulnar osteotomy and open Boyd (2), Proximal part of Plate and screws Yes (8) NA

(2007) reduction of radial head (8) Kocher (6) metaphysis (8) (8)

Lädermann16 Ulnar osteotomy (6) NA Proximal part of Plate and screws No NA

(2007) metaphysis (4), (5), and elastic nail

CORA (2) (1)

Nakamura12 Ulnar osteotomy, open reduction of Kocher Proximal part of Plate and screws No Forearm fascia

(2009) radial head, and annular ligament metaphysis (22) (22) (NR); remnant

reconstruction (22) annular ligament

augmented with

palmaris longus

(NR)

Rahbek23 Ulnar osteotomy, open reduction of Boyd Proximal part of Steinmann pin (9), Yes (7; if deemed Remnant annular

(2011) radial head, and annular ligament metaphysis (16) and plate and unstable ligament (10)

reconstruction (16) screws (7) intraoperatively)

Stitgen17 (2012) Ulnar osteotomy, open reduction of NR Proximal part of Plate and screws No Triceps (1)

radial head, and annular ligament metaphysis (1) (1)

reconstruction (1)

Song27 (2012) Ulnar osteotomy and closed Boyd Proximal part of Plate and screws No Forearm fascia (2)

reduction of radial head (8); ulnar metaphysis (10) (6),

osteotomy, open reduction of radial intramedullary

head, annular ligament nail (2), external

reconstruction (2) fixation (1), and

cast (1)

Lu31 (2013) Ulnar osteotomy, open reduction of Henry Proximal part of External fixation Yes (1) Remnant annular

radial head, external fixation (NR); metaphysis (33) (33) ligament (NR)

ulnar osteotomy, open reduction of

radial head, external fixation,

annular ligament reconstruction

(NR)

Delpont9 Ulnar osteotomy and open Boyd Proximal part of Plate and screws Yes (5) Triceps (12)

(2014) reduction of radial head (16); ulnar metaphysis (28) (28)

osteotomy, open reduction of radial

head, annular ligament

reconstruction (12)

Bor19 (2015) Ulnar osteotomy and external NA Proximal part of External fixation No NA

fixation metaphysis (4) (4)

*NA 5 not applicable, NR 5 not reported, and CORA 5 center of rotation of angulation. †The values in parentheses are given as the number of patients.

osteotomy and annular ligament recon- produce good long-term clinical and demonstrated a negative correlation

struction in 22 children with a mean final radiographic outcomes in patients who between patient age and interval from

follow-up of 7 years12. The mean Mayo underwent the surgical procedure at the injury to open reduction with radio-

Elbow Performance Index (MEPI) and age of ,12 years or within 3 years from graphic outcomes. In their series, annular

motion improved at the time of the final the date of the injury12. ligament reconstruction and trans-

follow-up. Radiographic outcomes were Rahbek et al. reported on long-term radiocapitellar Kirschner wire fixation did

good (maintained radial-head reduction, outcomes of open reduction of the radial not affect radiographic outcomes or

no osteoarthritic changes) in 15 patients head with posterior-bending elongation patient pain scores when compared with

and fair (radial-head subluxation or oste- ulnar osteotomy in 16 children performed procedures in which they were not per-

oarthritic changes) in 7 patients. Notably, by 1 of 2 surgeons at a mean final follow- formed. They did not recommend for or

all patients who underwent the surgical up of 8 years. Cases varied in terms of against annular ligament reconstruction as

procedure at the age of ,12 years or who annular ligament reconstruction com- their study was likely underpowered to

had an interval from the date of the injury pared with annular ligament resection as detect an effect on outcomes. However,

to the date of the surgical procedure of well as plate compared with Steinmann they emphasized that it is possible to

,3 years had good radiographic and pin fixation of the ulnar osteotomy. Ra- achieve a radial-head reduction that is

clinical outcomes. Thus, the authors diocapitellar pinning was also utilized if dynamically stable and provides good

concluded that open reduction for missed there was residual radial-head instability radiographic and clinical outcomes at a

Monteggia lesions could be expected to following ulnar osteotomy. They also long-term follow-up through posterior-

JUNE 2018 · VOLUME 6, ISSUE 6 · e2 11

| Missed Pediat r ic Monteg g ia Fractures

TABLE IV Outcomes for Missed Pediatric Monteggia Fracture Studies*

Flexion and Extension at Final Pronation and Supination at

Study Follow-up† Follow-up† (deg) Final Follow-up† (deg) Complications‡

54

Bell Tawse (1965) 2.1 yr (1 to 5.5 yr) NR (100 to “full”) and NR (240 to “full”) NR (“Loss of pronation” to “full”) Recurrent radial-head

and NR (“full”) dislocation (1)

Lloyd-Roberts40 (1977) 5.39 yr (0.5 to 18 yr) NR (100 to “full”) and NR (220 to “full”) NR (45 to “full”) and NR (45 to Radial-head subluxation (2)

“full”)

Hurst29 (1983) NR NR NR NR

Fowles3 (1983) 4.6 yr (1 to 8 yr) 157 (125 to 180) and 26 (225 to 0) 76 (60 to 90) and 88 (80 and 90) Loss of rotation (3); residual

valgus carrying angle (2);

radiocapitellar dysplasia (2);

radial-head subluxation (1)

Kalamchi56 (1986) 3 yr (1 to 5 yr) “Full” and “full” 60 and 90 None

Hirayama53 (1987) 3 yr (1.5 to 7 yr) NR NR Loss of pronation (4); persistent

radial nerve palsy (2); plate

fracture (2)

Stoll21 (1992) 3.25 yr (0.5 to 8 yr) 142.1 (130 to 155) and 8.1 (0 to 15) 56.9 (45 to 80) and 51.9 (0 to 80) Loss of radial-head reduction (1;

initially treated without

transcapitellar Kirschner wire

and converted to Kirschner

wire); loss of radial-head

reduction with pain and cubitus

valgus necessitating radial-

head resection (1)

Oner49 (1993) 3.3 yr (1 to 7 yr) NR NR Radioulnar synostosis (1);

radial-neck notching (2); radial-

head subluxation (2)

Best30 (1994) 21.8 mo (11 to 53 mo) “Full” and 21.2 (25 to “full”) 81.7 (60 to 90) and 83.3 (70 to Residual varus (1); loss of radial-

90) head reduction necessitating

reoperation (1)

Tajima20 (1995) NA NR NR Proximal radial migration with

subsequent positive ulnar

variance distally following

radial-head resection (5)

Rodgers11 (1996) 4.5 yr (2 to 11.25 yr) NR 49 (5 to 85) and 64 (35 to 90) Ulnar nerve palsy (2); loss of

fixation of ulnar osteotomy (2);

nonunion of ulnar osteotomy (1);

loss of radial-head reduction (3)

Devnani46 (1997) 3.66 yr (1 to 5 yr) 127.5 (125 to 130) and 25 (220 to 10) 16.66 (10 to 20) and “full” Loss of pronation (3)

Cappellino34 (1998) 25.7 (12 to 44) NR NR None

Inoue32 (1998) 5 yr (1 to 12 yr) 138 (130 to 150) and 20.5 (25 to 0) 55 (30 to 90) and 73 (30 to 100) Persistent radial-head

dislocation (3); unstable valgus

deformity of the elbow (1);

radiohumeral osteoarthritis

Seel33 (1999) 47.7 mo (12 to 96 mo) 132.7 (95 to 145) and 211 (240 to 0) 63.6 (5 to 90) and 81.4 (60 to 90) Recurrent radial-head

subluxation (2)

De Boeck35 (2000) 4.3 (2 to 8.6) 131.25 (120 to 140) and 26.25 (210 to 0) 77.5 (70 to 90) and 85 (80 to 90) None

Exner22 (2001) 5 yr (1 to 9 yr) 142.5 (140 to 145) and 10 (NR) 80 and 90 None

Horii51 (2002) 3 yr (0.66 to 12 yr) 134.2 (NR) and 3 (NR) 56.5 (NR) and 76.5 (NR) Radial-head subluxation (4),

radial-head redislocation (7;

prior to changing to ulnar

angulation osteotomy)

Kim39 (2002) 43.5 mo (12 to 105 mo) Mean flexion-extension arc, 125.0 (NR) 57.9 (45 to 75) and 74.6 (40 to Loss of pronation (7); loss of

85) pronation, supination, flexion,

and extension (1); radial-neck

notching (3); heterotopic

ossification (2); superficial

infection (1); radioulnar

synostosis (1)

Degreef25 (2004) 18 mo (4 to 36 mo) “Full” and “full” “Full” and “full” None

David-West7 (2005) 2.5 yr (1 to 5 yr) 108.8 (100 to 120) and 3.1 (0 to 10) 43.1 (30 to 60) and 61.3 (30 to Loss of radial-head reduction (2;

85) initially treated without

transcapitellar Kirschner wire

and converted to Kirschner wire)

continued

12 JUNE 2018 · VOLUME 6, ISSUE 6 · e2

Missed Pediatr ic Monteg gia Fractures |

TABLE IV (continued )

Flexion and Extension at Final Pronation and Supination at

Study Follow-up† Follow-up† (deg) Final Follow-up† (deg) Complications‡

24

Hasler (2005) 20 mo (6 to 60 mo) 136 (110 to 150) and 0 (220 to 10) 75.4 (40 to 90) and 80 (20 to 90) Delayed union of ulnar

osteotomy (2); superficial pin-

track infections (2)

Hui28 (2005) 4.25 yr (1 to 6 yr) 138.7 (90 to 150) and 2 (0 to 10) 76 (30 to 90) and 84 (60 to 90) Delayed union of ulnar

osteotomy (1); transient radial

nerve palsy (1), redislocation (1);

persistent radiocapitellar

subluxation (1)

Koslowsky18 (2006) 27.33 (26 to 30) 136.7 (130 to 140) and 16.7 (10 to 20) 90 and 90 None

Wang26 (2006) 7.8 yr (1 to 16.9 yr) 133 (110 to 145) and 1 (0 to 10) 67 (30 to 90) and 79 (30 to 90) Delayed union of ulnar

osteotomy (1); transient

posterior interosseous nerve

palsy (1); redislocation (1)

Belangero59 (2007) 4.5 (2 to 12) 135 and 0 76.25 (60 to 90) and 88.75 (80 to None

90)

Lädermann16 (2007) 3 yr (1.5 to 4.3 yr) 132.5 (120 to 140) and 4.2 (0 to 15) 85 (70 to 90) and 90 Nonunion (1)

Nakamura12 (2009) 7 yr (2 to 17 yr) 137.5 (130 to 145) and 2.3 (220 to 20) 66.8 (40 to 90) and 89.5 (70 to Delayed union ulnar osteotomy

95) (2); elbow contracture requiring

soft-tissue release (2)

Rahbek23 (2011) 8 yr (3 to 17 yr) NR NR Arthrosis or radial-head

subluxation (4); late dislocated

radial head (2)

Stitgen17 (2012) 5 mo “Full” and “full” 10 and “full” None

Song27 (2012) 10 yr (3 to 20 yr) NR NR Redislocation (3)

Lu31 (2013) 38 mo (12 to 86 mo) 130 (115 to 140) and 5 (5 to 10) 80 (70 to 90) and 80 (65 to 90) Redislocation (3; within 1 week),

delayed union ulnar osteotomy

(2; treatment with iliac crest

bone graft)

Delpont9 (2014) 6 yr (2 to 34 yr) 127 (110 to 140) and 24 (225 to 0) 66 (0 to 90) and 77 (20 to 90) Recurrent dislocation of the

radial head despite annular

ligament reconstruction (2);

osteoarthritis (3; 2 with

radiocapitellar pin); recurrent

subluxation of radial head (5;

every radiocapitellar pin)

Bor19 (2015) 3.75 yr (2 to 6 yr) 150 and 0 90 and 85 (70 to 90) Pin-track infection (1)

*NR 5 not recorded. †The values are given as the mean, with or without the range in parentheses. The values in parentheses are the number of patients.

bending elongation osteotomy of the ulna with osteotomy and correction of the Wang and Chang reported on a

alone. Finally, they did not demonstrate ulnar deformity alone. Three patients case series of 13 children treated with a

an effect of transradiocapitellar fixation who did not undergo annular ligament uniform surgical protocol26. Their

with a Kirschner wire on radiographic or reconstruction needed a revision pro- described technique used a single inci-

clinical outcomes, but recommended cedure for early redislocation of the sion via the Boyd approach with

against it if a stable radial-head reduction radial head and underwent revision of debridement of the remnant annular

could be obtained without it23. the ulnar osteotomy without annular ligament, osteotomy and correction of

Song et al. reported on outcomes in ligament reconstruction because the the ulnar deformity as dictated by

10 patients undergoing ulnar osteotomy original deformity was undercorrected. reduction of the radiocapitellar joint

with correction of ulnar deformity with a One patient had persistent radial-head with plate and screw fixation, and

mean final follow-up of 10 years27. Nine dislocation because of an uncorrected annular ligament reconstruction using a

patients reported excellent functional proximal radial deformity not appreci- strip of forearm fascia. The mean final

outcomes, and 1 patient reported a good ated at initial treatment. Similar to follow-up was 7.8 years. Restoration of a

functional outcome. All osteotomies Rahbek et al.23, these authors con- normal flexion-extension arc was noted

healed at 6 weeks without the use of cluded that annular ligament recon- to be more predictable than restoration

bone-grafting. Two patients underwent struction is not a necessary component of full pronosupination. One patient

annular ligament reconstruction and of maintaining a reduced and stable with a fair outcome and inadequate

the remaining 8 patients were treated radiocapitellar joint. motion had a redislocation that was

JUNE 2018 · VOLUME 6, ISSUE 6 · e2 13

| Missed Pediat r ic Monteg g ia Fractures

TABLE V Preferred Treatment Algorithm for Missed Pediatric Monteggia Injuries

Approach Single-incision, lateral approach through Kocher interval or Boyd approach

Ulnar osteotomy Crescentic osteotomy (to increase surface area for union) with angular correction of the ulnar deformity without

ulnar lengthening. Fixed in place with plate-and-screw fixation.

Radial-head reduction Initially attempt to reduce radial head into intact annular ligament. If this is unsuccessful, pie-crust annular ligament

and attempt second reduction. If this remains unsuccessful, incise annular ligament and repair around radial neck

following reduction.

Assessment of Fluoroscopic examination of radiocapitellar joint through full elbow range of motion. If radiocapitellar joint noted to

radiocapitellar stability be unstable, reassess adequacy of corrective ulnar osteotomy. If further ulnar deformity correction does not yield a

stable radiocapitellar joint, consider reinforcement of annular ligament repair with triceps fascia.

Postoperative Univalved long arm cast with overwrap at 1 week postoperatively. Long arm cast maintained for 6 weeks

management postoperatively, at which point the cast is removed and range of motion is initiated. Progressive increase in weight-

bearing and active range of motion as dictated by clinical and radiographic assessment of osteotomy healing, with

expected full activity without restrictions at 4 to 6 months postoperatively.

attributed to undercorrection of the radiocapitellar articulation and annu- whom the native annular ligament is

ulnar deformity. This patient under- lar ligament reconstruction along with inadequate or in whom reduction of the

went revision ulnar osteotomy and supplemental radiocapitellar pinning radiocapitellar joint necessitates debride-

demonstrated a reduced radiocapitellar directed at increasing the stability of ment of the interposed annular ligament.

joint at the time of the final follow-up. this relationship. Most of the modern The summary of a preferred technique for

One patient with an excellent outcome literature has transitioned to a focus on management of these injuries is included

had a delayed union of the ulna that the correction of the ulnar deformity, as in Table V. Further prospective study is

authors attributed to a 2-mm gap in the the ulnar deformity has been demon- necessary to determine optimal treatment

osteotomy site following plate-and- strated to splint the radial head in a of these injuries, with recognition that the

screw fixation and recommended bone- dislocated position through the inter- rarity of this injury presents a great chal-

grafting for gapping of $2 mm. The osseous membrane. Various tech- lenge to high-quality study design.

authors concluded that their proposed niques for osteotomy and fixation are

technique provided excellent functional described, and it is our belief that a James Hubbard, MD1,2,

outcomes and range of motion at the crescentic osteotomy of the ulna Aakash Chauhan, MD, MBA1,

long-term follow-up and that forearm without lengthening minimizes the Ryan Fitzgerald, MD3,

Reid Abrams, MD1,

fascia was a suitable alternative annular risk of osteotomy nonunion. The Scott Mubarak, MD2,

ligament reconstruction graft26. degree of ulnar correction is dictated by Mark Sangimino, MD4

the stability of the radiocapitellar joint

1Division of Hand, Upper Extremity, and

Conclusions on intraoperative fluoroscopic exami-

Pediatric Monteggia injuries represent nation through a full range of motion at Microvascular Surgery, Department of

Orthopaedic Surgery, University of

a rare upper-extremity fracture pat- the elbow. Correction of the deformity California, San Diego (UCSD), San Diego,

tern, and they may be easily missed. is increased until the radiocapitellar California

After as little as 2 weeks, a neglected joint is found to be stable in all posi-

2Department of Pediatric Orthopaedic

Monteggia injury can present a serious tions of flexion, extension, and pro-

Surgery, Rady Children’s Hospital, San

clinical challenge, often necessitating nosupination. Various supplemental

Diego, California

operative intervention. Closed treat- techniques directed at increasing the

ment and “skillful neglect,” as stability of the radiocapitellar joint are 3Department of Pediatric Orthopaedic

described by Blount47, represent the described and may be used at the discre- Surgery, Riley Children’s Hospital,

earliest management strategy for these tion of the treating surgeon as dictated by Indianapolis, Indiana

injuries; however, this has largely fallen the perceived stability of the radio- 4Division of Pediatric Orthopaedic

out of favor as many authors have rec- capitellar joint following ulnar osteotomy Surgery, Department of Orthopaedic

ognized that surgical radiocapitellar and indirect reduction. Our preferred Surgery, Allegheny General Hospital,

reduction is possible and provides good method of secondary stabilization is Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

functional outcomes prior to onset of reduction of the radial head into the

chronic pathologic remodeling of the native annular ligament as this ligament is E-mail address for A. Chauhan: achau-

han1000@gmail.com

radial head and capitellum. Histori- often intact following radial-head dislo-

cally, operative techniques have cation in the pediatric population. ORCID iD for A. Chauhan: 0000-0002-

focused on direct reduction of the Reconstruction is reserved for patients in 1195-2491

14 JUNE 2018 · VOLUME 6, ISSUE 6 · e2

Missed Pediatr ic Monteg gia Fractures |

References 18. Koslowsky TC, Mader K, Wulke AP, acquired dislocation of the radial head. J

Gausepohl T, Pennig D. Operative treatment of Pediatr Orthop. 1998 May-Jun;18(3):410-4.

1. Ring D, Waters PM. Operative fixation of chronic Monteggia lesion in younger children: a

Monteggia fractures in children. J Bone Joint 35. De Boeck H. Treatment of chronic isolated

report of three cases. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. radial head dislocation in children. Clin Orthop

Surg Br. 1996 Sep;78(5):734-9. 2006 Jan-Feb;15(1):119-21. Relat Res. 2000 Nov;380:215-9.

2. Landin LA. Fracture patterns in children. 19. Bor N, Rubin G, Rozen N, Herzenberg JE.

Analysis of 8,682 fractures with special reference 36. Tompkins DG. The anterior Monteggia

Chronic anterior Monteggia lesions in children: fracture: observations on etiology and

to incidence, etiology and secular changes in a report of 4 cases treated with closed reduction

Swedish urban population 1950-1979. Acta treatment. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1971 Sep;

by ulnar osteotomy and external fixation. J 53(6):1109-14.

Orthop Scand Suppl. 1983;202:1-109. Pediatr Orthop. 2015 Jan;35(1):7-10.

3. Fowles JV, Sliman N, Kassab MT. The 37. Letts M, Locht R, Wiens J. Monteggia

20. Tajima T, Yoshizu T. Treatment of long- fracture-dislocations in children. J Bone Joint

Monteggia lesion in children. Fracture of the

standing dislocation of the radial head in ne- Surg Br. 1985 Nov;67(5):724-7.

ulna and dislocation of the radial head. J Bone

glected Monteggia fractures. J Hand Surg Am.

Joint Surg Am. 1983 Dec;65(9):1276-82. 38. Lincoln TL, Mubarak SJ. “Isolated” traumatic

1995 May;20(3 Pt 2):S91-4.

4. Bado JL. The Monteggia lesion. Clin Orthop radial-head dislocation. J Pediatr Orthop. 1994

21. Stoll TM, Willis RB, Paterson DC. Treatment Jul-Aug;14(4):454-7.

Relat Res. 1967 Jan-Feb;50:71-86.

of the missed Monteggia fracture in the child. J

5. Dormans JP, Rang M. The problem of Bone Joint Surg Br. 1992 May;74(3):436-40. 39. Kim HT, Conjares JNV, Suh JT, Yoo CI.

Monteggia fracture-dislocations in children. Chronic radial head dislocation in children,

22. Exner GU. Missed chronic anterior part 1: pathologic changes preventing

Orthop Clin North Am. 1990 Apr;21(2):251-6.

Monteggia lesion. Closed reduction by gradual stable reduction and surgical correction.

6. Gleeson AP, Beattie TF. Monteggia fracture- lengthening and angulation of the ulna. J Bone

dislocation in children. J Accid Emerg Med. J Pediatr Orthop. 2002 Sep-Oct;22(5):

Joint Surg Br. 2001 May;83(4):547-50. 583-90.

1994 Sep;11(3):192-4.

23. Rahbek O, Deutch SR, Kold S, Søjbjerg JO, 40. Lloyd-Roberts GC, Bucknill TM. Anterior

7. David-West KS, Wilson NIL, Sherlock DA, Møller-Madsen B. Long-term outcome after

Bennet GC. Missed Monteggia injuries. Injury. dislocation of the radial head in children:

ulnar osteotomy for missed Monteggia fracture aetiology, natural history and

2005 Oct;36(10):1206-9. Epub 2005 Mar 28. dislocation in children. J Child Orthop. 2011 management. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1977

8. Freedman L, Luk K, Leong JC. Radial head Dec;5(6):449-57. Epub 2011 Oct 16. Nov;59-B(4):402-7.

reduction after a missed Monteggia fracture: 24. Hasler CC, Von Laer L, Hell AK. Open

brief report. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1988 Nov; 41. Garg R, Fung BKK, Chow SP, Ip WY. Surgical

reduction, ulnar osteotomy and external

70(5):846-7. management of radial head dislocation in

fixation for chronic anterior dislocation of the

quadriplegic cerebral palsy — a 5 year follow-

9. Delpont M, Jouve JL, Sales de Gauzy J, head of the radius. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2005

up. J Hand Surg Eur Vol. 2007 Dec;32(6):725-6.

Louahem D, Vialle R, Bollini G, Accadbled F, Jan;87(1):88-94.

Epub 2007 Aug 2.

Cottalorda J. Proximal ulnar osteotomy in the 25. Degreef I, De Smet L. Missed radial head

treatment of neglected childhood Monteggia 42. Morrey BF, An KN. Articular and

dislocations in children associated with ulnar

lesion. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2014 Nov; ligamentous contributions to the stability of the

deformation: treatment by open reduction and

100(7):803-7. Epub 2014 Oct 7. elbow joint. Am J Sports Med. 1983 Sep-Oct;

ulnar osteotomy. J Orthop Trauma. 2004 Jul;

11(5):315-9.

10. Holst-Nielsen F, Jensen V. Tardy posterior 18(6):375-8.

interosseous nerve palsy as a result of an 43. Chen WS. Late neuropathy in chronic

26. Wang MN, Chang WN. Chronic

unreduced radial head dislocation in dislocation of the radial head. Report of two

posttraumatic anterior dislocation of the radial

Monteggia fractures: a report of two cases. J cases. Acta Orthop Scand. 1992 Jun;63(3):

head in children: thirteen cases treated by open

Hand Surg Am. 1984 Jul;9(4):572-5. 343-4.

reduction, ulnar osteotomy, and annular

11. Rodgers WB, Waters PM, Hall JE. Chronic ligament reconstruction through a Boyd 44. Storen G. Traumatic dislocation of the radial

Monteggia lesions in children. Complications incision. J Orthop Trauma. 2006 Jan;20(1):1-5. head as an isolated lesion in children; report of

and results of reconstruction. J Bone Joint Surg one case with special regard to roentgen

27. Song KS, Ramnani K, Bae KC, Cho CH, Lee KJ,

Am. 1996 Sep;78(9):1322-9. diagnosis. Acta Chir Scand. 1959 Jan 31;116(2):

Son ES. Indirect reduction of the radial head in

144-7.

12. Nakamura K, Hirachi K, Uchiyama S, children with chronic Monteggia lesions. J

Takahara M, Minami A, Imaeda T, Kato H. Long- Orthop Trauma. 2012 Oct;26(10):597-601. 45. Gyr BM, Stevens PM, Smith JT. Chronic

term clinical and radiographic outcomes after Monteggia fractures in children: outcome after

28. Hui JHP, Sulaiman AR, Lee HC, Lam KS, Lee

open reduction for missed Monteggia fracture- treatment with the Bell-Tawse procedure. J

EH. Open reduction and annular ligament

dislocations in children. J Bone Joint Surg Am. Pediatr Orthop B. 2004 Nov;13(6):402-6.

reconstruction with fascia of the forearm in

2009 Jun;91(6):1394-404. chronic Monteggia lesions in children. J Pediatr 46. Devnani AS. Missed Monteggia fracture

13. Tubbs RS, O’Neil JT Jr, Key CD, Zarzour JG, Orthop. 2005 Jul-Aug;25(4):501-6. dislocation in children. Injury. 1997 Mar;28(2):

Fulghum SB, Kim EJ, Lyerly MJ, Shoja MM, 131-3.

29. Hurst LC, Dubrow EN. Surgical treatment of

George Salter E, Jerry Oakes W. The oblique symptomatic chronic radial head dislocation: a 47. Blount WP. Fractures in children. Baltimore:

cord of the forearm in man. Clin Anat. 2007 May; Williams & Wilkins; 1954.

neglected Monteggia fracture. J Pediatr

20(4):411-5. Orthop. 1983 May;3(2):227-30. 48. Papandrea R, Waters PM. Posttraumatic

14. Captier G, Canovas F, Mercier N, Thomas E, reconstruction of the elbow in the pediatric

30. Best TN. Management of old unreduced

Bonnel F. Biometry of the radial head: patient. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2000 Jan;370:

Monteggia fracture dislocations of the elbow in

biomechanical implications in pronation and 115-26.

children. J Pediatr Orthop. 1994 Mar-Apr;14(2):

supination. Surg Radiol Anat. 2002 Dec;24(5):

193-9. 49. Oner FC, Diepstraten AF. Treatment of

295-301. Epub 2002 Nov 1.

31. Lu X, Kun Wang Y, Zhang J, Zhu Z, Guo Y, Lu chronic post-traumatic dislocation of the radial

15. Shah AS, Waters PM. Monteggia fracture-

M. Management of missed Monteggia fractures head in children. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1993 Jul;

dislocation in children. In: Flynn JM, Skaggs

with ulnar osteotomy, open reduction, and 75(4):577-81.

DL, Waters PM, editors. Rockwood and

dual-socket external fixation. J Pediatr Orthop. 50. Bhaskar A. Missed Monteggia fracture in

Wilkins’ fractures in children. 8th ed.

2013 Jun;33(4):398-402. children: is annular ligament reconstruction

Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health; 2014.

p 527-63. 32. Inoue G, Shionoya K. Corrective ulnar always required? Indian J Orthop. 2009 Oct;

osteotomy for malunited anterior Monteggia 43(4):389-95.

16. L ädermann A, Ceroni D, Lef èvre Y,

lesions in children. 12 patients followed for 1-12 51. Horii E, Nakamura R, Koh S, Inagaki H, Yajima

De Rosa V, De Coulon G, Kaelin A. Surgical

years. Acta Orthop Scand. 1998 Feb;69(1):73-6. H, Nakao E. Surgical treatment for chronic radial

treatment of missed Monteggia lesions in

children. J Child Orthop. 2007 Oct;1(4): 33. Seel MJ, Peterson HA. Management of head dislocation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002

237-42. Epub 2007 Aug 29. chronic posttraumatic radial head Jul;84(7):1183-8.

17. Stitgen A, McCarthy JJ, Nemeth BA, Garrels dislocation in children. J Pediatr Orthop. 52. Oka K, Murase T, Moritomo H, Sugamoto K,

K, Noonan KJ. Ulnar fracture with late radial 1999 May-Jun;19(3):306-12. Yoshikawa H. Morphologic evaluation of

head dislocation: delayed Monteggia fracture. 34. Cappellino A, Wolfe SW, Marsh JS. Use of chronic radial head dislocation: three-

Orthopedics. 2012 Mar 7;35(3):e434-7. a modified Bell Tawse procedure for chronic dimensional and quantitative analyses. Clin

JUNE 2018 · VOLUME 6, ISSUE 6 · e2 15

| Missed Pediat r ic Monteg g ia Fractures

Orthop Relat Res. 2010 Sep;468(9):2410-8. Epub 55. Aufranc OE, Jones WN, Bierbaum BE. Late one incision. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1940;71:

2010 Mar 4. traumatic dislocation of the radial head. JAMA. 86-8.

53. Hirayama T, Takemitsu Y, Yagihara K, Mikita A. 1969 Jun 30;208(13):2465-7. 58. Mehta SD. Flexion osteotomy of ulna for

Operation for chronic dislocation of the radial 56. Kalamchi A. Monteggia fracture- untreated Monteggia fracture in children. Ind J

head in children. Reduction by osteotomy of the dislocation in children. Late treatment in two Surg. 1985;47:15-9.

ulna. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1987 Aug;69(4):639-42. cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1986 Apr;68(4): 59. Belangero WD, Livani B, Zogaib RK.

54. Bell Tawse AJS. The treatment of malunited 615-9. Treatment of chronic radial head dislocations in

anterior Monteggia fractures in children. J Bone 57. Boyd HB. Surgical exposure of the ulna children. Int Orthop. 2007 Apr;31(2):151-4. Epub

Joint Surg Br. 1965 Nov;47(4):718-23. and proximal third of the radius through 2006 Jun 2.

16 JUNE 2018 · VOLUME 6, ISSUE 6 · e2

You might also like

- I. X-Ray Image: Hindfoot Fractures By: Jeremy Tan and Sarah HillDocument8 pagesI. X-Ray Image: Hindfoot Fractures By: Jeremy Tan and Sarah HillSheril MarekNo ratings yet

- Z Effect & Reverse Z Effect in PFNDocument7 pagesZ Effect & Reverse Z Effect in PFNNandan SurNo ratings yet

- Ankle Fractures: A Literature Review of Current Treatment MethodsDocument13 pagesAnkle Fractures: A Literature Review of Current Treatment Methodsadrian1989No ratings yet

- Management of Avn HipDocument13 pagesManagement of Avn Hipterencedsza100% (1)

- SUTGMultiLocJ9981A PDFDocument60 pagesSUTGMultiLocJ9981A PDFLouis MiuNo ratings yet

- Ligamentous Injuries About The Ankle and Subtalar Joints: Hans Zwipp, MD, PHD, Stefan Rammelt, MD, Rene Grass, MDDocument35 pagesLigamentous Injuries About The Ankle and Subtalar Joints: Hans Zwipp, MD, PHD, Stefan Rammelt, MD, Rene Grass, MDAnonymous kdBDppigENo ratings yet