Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Oaths and Vows - The Power of Words: A D'var Torah On Parashat Matot (By Alan I. Friedman

Uploaded by

ShlomoOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Oaths and Vows - The Power of Words: A D'var Torah On Parashat Matot (By Alan I. Friedman

Uploaded by

ShlomoCopyright:

Available Formats

Oaths and Vows — The Power of Words

A D’var Torah on Parashat Matot (Num. 30:2 – 32:42)

By Alan I. Friedman

“Vay’dabeir Moshe el-rashei ha-matot liv’nei Yisrael….”

“Moses spoke to the heads of the Israelite tribes….”

The discussion of oaths and vows in Parashat Matot focuses almost

exclusively on the rights of a father or husband to annul or uphold a

woman’s vows. As Reform Jews in the 21st century, we find it difficult to

understand male-dominated societal standards that placed strict limits on a

woman’s exercise of free will and self-determination. We forget that only in

the last 120-or-so years, and only in progressive countries of the Western

world, have women begun to emerge from millennia of inferior social and

legal status. Certainly in the biblical Near East, at the time when the

concepts of Parashat Matot were being codified, men had rights that women

did not, and male dominance of human affairs was pervasive.

But we will not dwell on these aspects of Matot. Rather, we will examine the

characteristics of oaths and vows, the distinctions between these two types

of pledges, the rationale for speech adding potency to an oath or vow, and

the mechanism for annulment.

The two Hebrew words that we will focus on are neder (plural nedarim) and

sh’vuah1 (plural sh’vuot). Although there is no English equivalent for neder;

it is commonly translated as “vow,” meaning a pledge to do something; but

“vow” doesn’t convey the full meaning. There are two types of nederim: the

first type empowers a person to prohibit to himself or herself something that

the Torah permits (for example, “I will not eat meat for the next 30 days”);

the second type of neder obligates a person to perform an optional

commandment (such as donating to a particular charity of visiting a sick

friend daily). With the exception of a neder to perform a commandment,

nedarim cannot be used to obligate oneself to perform an act. Parashat

Matot concerns itself only with the first type of neder, a voluntarily adopted

prohibition.2

The second Hebrew word that is key to this passage is sh’vuah, meaning an

“oath.” By invoking a sh’vuah, a person may either prohibit himself from

performing an act, or require himself to perform an act.

“Conceptually there is a great difference between a neder and [a sh’vuah]. A

neder changes the status of an object: for example, if I have made an apple

Do not confuse: h[bX (sh’vuah) = oath; [wbX (shavua) = week

1

2

The Chumash: The Stone Edition; Edited by Rabbis Nosson Scherman and Meir Zlotowitz; Mesorah

Publications, Ltd.; 1993; p. 900.

forbidden to myself, the apple has the status of a forbidden food to me, and

therefore I may not enjoy the apple. In contrast, [a sh’vuah] places an

obligation only on the person: for example, if I have sworn to eat an apple,

there is a new obligation on me, but the halachic status of the apple itself is

unchanged.”3

Whenever a person makes a neder or a sh’vuah, the Torah obligates that

person to fulfill the pledge4. Jewish law further dictates that even if a person

simply expresses a willingness to perform a mitzvah, he or she is similarly

obligated to do so.5

What are the mechanics by which a vow takes effect? “Life and death are in

the power of the tongue,” advises Proverbs 18:21. Speech is the gateway

between the thoughts of the mind and the physical actions of the body.

Through speech one begins the trek of turning intentions into the reality of

action. It is for this reason that making a neder is so effective in binding a

person into doing the right thing.6

Why should a neder help a person perform a mitzvah that he or she is

already obligated to perform? Why can’t a person simply decide to do the

mitzvah and carry it out without expressing the intent verbally? Even

pledging to perform a mitzvah to which one is already obligated strengthens

one’s commitment by moving the intention toward reality. All that remains

is the purely physical act.7

Why does a person become any more obligated by expressing a desire

through the medium of speech than by thinking that same desire? A person

who invokes a neder or a sh’vuah places upon himself, upon others, or upon

objects a status equal to a commandment from the Torah. The neder or

sh’vuah creates a binding situation that otherwise would not have existed.8

The expression of a “word” imposes an obligating force upon the person

making the pledge; and as soon as the word is uttered, the promise is

considered binding.9 “Giving one’s word,” then, is not so much a point of

honor as it is a sacred and binding obligation.10 And, because a pledge is

sacred, it must not be broken. Failure to comply with the pledge makes the

3 Ibid., p. 900.

4 “If a man makes a vow to Adonai or takes an oath imposing an obligation on himself, he shall not

break his pledge; he must carry out all that has crossed his lips.” – Num. 30:3

5 Shulchan Aruch Yoreh De’ah 203.

6 “Speech Impediments,” by Ranon Cortell; Torah from Dixie; undated.

7 Ibid.

8 “How to Vow Your Audience,” Perceptions on the Parasha, by Rabbi Pinchas Winston; Project

Genesis; 2003.

9 “Holy Words,” by Rabbi Jordan D. Cohen; Associate Director of KOLEL – The Adult Centre for Liberal

Jewish Learning; undated.

10 Commentary by Rabbi Gerson D. Cohen, Chancellor Emeritus and Professor of Jewish History,

Jewish Theological Seminary of America; 1999.

person culpable for punishment, just as if he or she had violated an act or

restriction that had been commanded by the Torah. Such is the power of

speech.11

Nedarim and sh’vuot are serious because they are pledges to God. The Torah

does not even consider that one would make a pledge to God and then

default on it. In fact, there are no provisions for absolving a person of the

consequences for defaulting on a pledge.12 Perhaps that is why we read in

Ecclesiastes 5:4 that “it is better not to vow at all than to vow and not fulfill.”

In the Holiness Code, which we recite every Shabbat morning, we read, “You

shall not swear falsely by My Name, thereby desecrating the name of your

God.”13 The Hebrew verb for “desecrate” is chillul. The adjectival form,

chullin, is usually translated as “profane,” but actually has the sense of

“ordinary.” Since the Torah uses chillul regarding the breaking of one’s vow,

and since desecration has relevance only to the defilement of something that

is sacred, we may conclude that one’s speech is sacred.14 We see, then, that

breaking a pledge – that is, desecrating one’s word – is not just a personal

failure; it is a chillul ha-Shem, a profanation of God’s holy Name.15

Recognizing that nedarim and sh’vuot were often made on impulse or in

anger, and without due regard for the consequences,16 some rabbis

performed elaborate legal gymnastics – called hattarat nedarim, – to identify

legal loopholes and provide for the dissolution of vows.17

These legal processes in front of a Beit Din ultimately coalesced into the Kol

Nidrei, which we chant on Erev Yom Kippur. Since any violation of a neder

or sh’vuah can interfere with the atonement process, and since an individual

who has violated a pledge may not realize that he has done so, Kol Nidrei

provides an opportunity for absolution. “Kol Nidrei declares that in case an

individual made a vow or an oath during the past year and somehow forgot

and violated it inadvertently, he now realizes that he made a terrible mistake

and strongly regrets his hasty pronouncement. In effect he tells the ‘court’

… that had he realized the gravity and severity of violating an oath, he never

would have uttered it in the first place. He thus begs for forgiveness and

understanding.”18

11 Rabbi Pinchas Winston; op. cit.

12 Rabbi Jordan D. Cohen, op. cit.

13 Parashat K’doshim, Lev. 19:12.

14 Commentary by Rabbi Yoseph Kalatsky, Dean of The Yad Avraham Institute.

15 “Sanctifying and Profaning the Name,” The Torah – A Modern Commentary; Edited by W. Gunther

Plaut; Union of American Hebrew Congregations; 1981; p. 892.

16 “Speak Out!” by Rabbi Sue Ann Wasserman; Department of Worship, Music, and Religious Living;

Union of American Hebrew Congregations (now Union for Reform Judaism); July 10, 1999.

17 Rabbi Jordan D. Cohen, op. cit.

18 “The Origin and Purpose of Kol Nidrei,” by Rabbi Doniel Neustadt, Congregation Young Israel,

Cleveland, and Principal of Yavne Teachers College; 2000.

Other rabbinic authorities maintain that Kol Nidrei, instead of annulling

existing nedarim and sh’vuot, declares as invalid (“null and void, without

power and without standing”) all future nedarim and sh’vuot that might be

uttered without sufficient forethought.19

What is the message of Parashat Matot for us today? We must be on guard

against making promises, commitments, and pledges that we do not intend

to keep or that we may not be able to keep. Words have power, and giving

one’s word creates a sacred and binding obligation. Let us use our words for

kiddush ha-Shem, sanctification of God’s holy Name.

AIF 07-09-04 Matot – DvarTorah.doc

19 Ibid.

You might also like

- Hineini in Our Lives: Learning How to Respond to Others through 14 Biblical Texts & Personal StoriesFrom EverandHineini in Our Lives: Learning How to Respond to Others through 14 Biblical Texts & Personal StoriesNo ratings yet

- Jewish Times 510Document24 pagesJewish Times 510ShlomoNo ratings yet

- From the Guardian's Vineyard on Sefer B'Reshith : (The Book of Genesis)From EverandFrom the Guardian's Vineyard on Sefer B'Reshith : (The Book of Genesis)No ratings yet

- Parashat Vayechi 5773 PDFDocument2 pagesParashat Vayechi 5773 PDFyudifeldNo ratings yet

- A Journey Through Torah: An Introduction to God’s Life Instructions for His ChildrenFrom EverandA Journey Through Torah: An Introduction to God’s Life Instructions for His ChildrenNo ratings yet

- במערבא אמרי - חנוכה תשפאDocument58 pagesבמערבא אמרי - חנוכה תשפאElie BashevkinNo ratings yet

- Is Halitah Necessary 2Document9 pagesIs Halitah Necessary 2ShlomoNo ratings yet

- Uncovering Judaism’s Soul: An Introduction to the Ideas of the TorahFrom EverandUncovering Judaism’s Soul: An Introduction to the Ideas of the TorahNo ratings yet

- Sefer BeMidbar as Sefer HaMiddot: The Book of Numbers as the Book of Character DevelopmentFrom EverandSefer BeMidbar as Sefer HaMiddot: The Book of Numbers as the Book of Character DevelopmentNo ratings yet

- Vayechi - "And He Lived": Seventeen YearsDocument6 pagesVayechi - "And He Lived": Seventeen YearsDavid MathewsNo ratings yet

- Shofar On ShabbosDocument12 pagesShofar On Shabbosapi-52200775No ratings yet

- A Jewish Ceremony for Newborn Girls: The Torah’s Covenant AffirmedFrom EverandA Jewish Ceremony for Newborn Girls: The Torah’s Covenant AffirmedNo ratings yet

- The TzedokimDocument1 pageThe TzedokimRabbi Benyomin HoffmanNo ratings yet

- Benjamin and Rose Berger Pesach To-Go - 5780Document68 pagesBenjamin and Rose Berger Pesach To-Go - 5780Robert Shur100% (1)

- UntitledDocument14 pagesUntitledoutdash2No ratings yet

- Shmuel Ettinger - The Hassidic Movement - Reality and IdealsDocument10 pagesShmuel Ettinger - The Hassidic Movement - Reality and IdealsMarcusJastrow0% (1)

- Vayechi, וַיְחִיDocument6 pagesVayechi, וַיְחִיDavid MathewsNo ratings yet

- Responding To Words, Responding To Blows: Parashah Insights Rabbi Yaakov HillelDocument4 pagesResponding To Words, Responding To Blows: Parashah Insights Rabbi Yaakov HillelHarav Michael ElkohenNo ratings yet

- The Sanctity of The Whole: Parashah Insights Rabbi Yaakov HillelDocument8 pagesThe Sanctity of The Whole: Parashah Insights Rabbi Yaakov HillelHarav Michael ElkohenNo ratings yet

- VayechiDocument7 pagesVayechiDavid MathewsNo ratings yet

- Facing Illness, Finding God: How Judaism Can Help You and Caregivers Cope When Body or Spirit FailsFrom EverandFacing Illness, Finding God: How Judaism Can Help You and Caregivers Cope When Body or Spirit FailsNo ratings yet

- Nitzavim VayelechDocument2 pagesNitzavim VayelechLivingTorahNo ratings yet

- Feyerabend Hebrew PDFDocument1 pageFeyerabend Hebrew PDFChrisNo ratings yet

- The Day After ShabbosDocument2 pagesThe Day After ShabbosRabbi Benyomin HoffmanNo ratings yet

- Chumash Detail DevarimDocument216 pagesChumash Detail Devarimdavid mejijaNo ratings yet

- Beis Moshiach #856Document39 pagesBeis Moshiach #856B. MerkurNo ratings yet

- Rabbi Yochanan and Raish LakishDocument4 pagesRabbi Yochanan and Raish LakishyadmosheNo ratings yet

- Shiras HaAzinuDocument2 pagesShiras HaAzinuRabbi Benyomin HoffmanNo ratings yet

- Mitokh HaOhel: HaftarotDocument12 pagesMitokh HaOhel: HaftarotKorenPub100% (1)

- Slavery and FreedomDocument9 pagesSlavery and FreedomHarav Michael ElkohenNo ratings yet

- Baruch She 'Amar Teaching Guide: by Torah Umesorah Chaim and Chaya Baila Wolf Brooklyn Teacher CenterDocument10 pagesBaruch She 'Amar Teaching Guide: by Torah Umesorah Chaim and Chaya Baila Wolf Brooklyn Teacher CenterMárcio de Carvalho100% (1)

- Yeshiva University - Shavuot To-Go For Families - Sivan 5768Document13 pagesYeshiva University - Shavuot To-Go For Families - Sivan 5768outdash2No ratings yet

- Ha-Madrikh (Hyman Goldin 1939, Rev. 1956) - TextDocument507 pagesHa-Madrikh (Hyman Goldin 1939, Rev. 1956) - TextArì Yaakov RuizNo ratings yet

- Seyder Tkhines The Forgotten Book of Common Prayer...Document284 pagesSeyder Tkhines The Forgotten Book of Common Prayer...dovbearNo ratings yet

- Mishna BeruraDocument6 pagesMishna Berurajose contrerasNo ratings yet

- The Ellis Family Edition: Volume 6 SampleDocument10 pagesThe Ellis Family Edition: Volume 6 SampleSam MillunchickNo ratings yet

- Tannaim ListDocument1 pageTannaim Listgjbrown888No ratings yet

- When God Is NearDocument17 pagesWhen God Is NearKorenPubNo ratings yet

- Toldos Selections From Rabbi Baruch EpsteinDocument3 pagesToldos Selections From Rabbi Baruch EpsteinRabbi Benyomin HoffmanNo ratings yet

- S&P Shabbat CustomsDocument13 pagesS&P Shabbat CustomsJohnny SolomonNo ratings yet

- The Voice of Silence: A Rabbi’S Journey into a Trappist Monastery and Other ContemplationsFrom EverandThe Voice of Silence: A Rabbi’S Journey into a Trappist Monastery and Other ContemplationsNo ratings yet

- Sichos In English, Volume 14: Sivan-Elul, 5742From EverandSichos In English, Volume 14: Sivan-Elul, 5742Rating: 1 out of 5 stars1/5 (1)

- Sukkah 45Document44 pagesSukkah 45Julian Ungar-SargonNo ratings yet

- Tishrei Part One 5777 EnglDocument60 pagesTishrei Part One 5777 EnglanherusanNo ratings yet

- Parashat MishpatimDocument9 pagesParashat MishpatimHarav Michael ElkohenNo ratings yet

- Tanya and The Written TorahDocument4 pagesTanya and The Written TorahRabbi Benyomin HoffmanNo ratings yet

- Timeline of Sefer VaYikraDocument1 pageTimeline of Sefer VaYikraRabbi Benyomin HoffmanNo ratings yet

- 08 5NatLInstProc67 (1953)Document22 pages08 5NatLInstProc67 (1953)Priyanka MaroorhNo ratings yet

- Descendants of The Anusim (Crypto - Jews) in Contemporary Mexico 2009Document239 pagesDescendants of The Anusim (Crypto - Jews) in Contemporary Mexico 200998fg09nm56sd100% (2)

- By Rav Alex Israel Shiur #28: Chapter 22 - Achav's Final BattleDocument6 pagesBy Rav Alex Israel Shiur #28: Chapter 22 - Achav's Final BattleShlomoNo ratings yet

- Center For Advanced Judaic Studies, University of PennsylvaniaDocument13 pagesCenter For Advanced Judaic Studies, University of PennsylvaniaShlomoNo ratings yet

- Z.gg#o-Yng - lS02.S2M-lcm-: Frequency WavelengthDocument2 pagesZ.gg#o-Yng - lS02.S2M-lcm-: Frequency WavelengthShlomoNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 128.197.26.12 On Wed, 11 May 2016 16:27:04 UTCDocument17 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 128.197.26.12 On Wed, 11 May 2016 16:27:04 UTCShlomoNo ratings yet

- Sefer Ha-Razim: Sefer Ha-Razim Does.2 The Subject Matter of Sefer Ha-Razim Consists Mainly ofDocument2 pagesSefer Ha-Razim: Sefer Ha-Razim Does.2 The Subject Matter of Sefer Ha-Razim Consists Mainly ofShlomoNo ratings yet

- (Semitica Viva) Assaf Bar-Moshe - The Arabic Dialect of The Jews of Baghdad - Phonology, Morphology, and Texts-Harrassowitz Verlag (2019)Document317 pages(Semitica Viva) Assaf Bar-Moshe - The Arabic Dialect of The Jews of Baghdad - Phonology, Morphology, and Texts-Harrassowitz Verlag (2019)Shlomo100% (2)

- SalturusumuDocument39 pagesSalturusumuShlomoNo ratings yet

- The Natural Law in The Buddhist Tradition (The Buddhist View of The World)Document28 pagesThe Natural Law in The Buddhist Tradition (The Buddhist View of The World)ShlomoNo ratings yet

- Intermediate Biblical Hebrew Grammar: Eric D. ReymondDocument355 pagesIntermediate Biblical Hebrew Grammar: Eric D. ReymondShlomo100% (20)

- (Agi Risko) Beginner's Finnish (Hippocrene BeginneDocument154 pages(Agi Risko) Beginner's Finnish (Hippocrene BeginneBeatrice TivadarNo ratings yet

- Intermediate Biblical Hebrew Grammar: Eric D. ReymondDocument355 pagesIntermediate Biblical Hebrew Grammar: Eric D. ReymondShlomo100% (20)

- The Targum To Canticles According To Six Yemen Mss Compared With The Textus ReceptusDocument20 pagesThe Targum To Canticles According To Six Yemen Mss Compared With The Textus ReceptusShlomoNo ratings yet

- (Studia Judaica 71) Moshe Bar-Asher, Aaron Koller-Studies in Classical Hebrew-Walter de Gruyter (2014)Document491 pages(Studia Judaica 71) Moshe Bar-Asher, Aaron Koller-Studies in Classical Hebrew-Walter de Gruyter (2014)Shlomo83% (6)

- Xa YeDocument72 pagesXa YeShlomoNo ratings yet

- The Legacy Of: MaimonidesDocument22 pagesThe Legacy Of: MaimonidesShlomoNo ratings yet

- PaszDocument339 pagesPaszShlomoNo ratings yet

- The Targum To Canticles According To Six Yemen Mss Compared With The Textus Receptus PDFDocument115 pagesThe Targum To Canticles According To Six Yemen Mss Compared With The Textus Receptus PDFShlomoNo ratings yet

- Food and Identity in Early Rabbinic JudaismDocument238 pagesFood and Identity in Early Rabbinic JudaismShlomo100% (1)

- Anthony J. Saldarini Fathers According To Rabbi Nathan Abot de Rabbi Nathan Version BDocument348 pagesAnthony J. Saldarini Fathers According To Rabbi Nathan Abot de Rabbi Nathan Version BBibliotheca midrasicotargumicaneotestamentariaNo ratings yet

- Research Into The Cairo Genizah and The PDFDocument33 pagesResearch Into The Cairo Genizah and The PDFShlomoNo ratings yet

- ExLing2016proceedings PDFDocument201 pagesExLing2016proceedings PDFShlomoNo ratings yet

- Judeo Spanish Lester VicetDocument103 pagesJudeo Spanish Lester VicetShlomoNo ratings yet

- Amharic English Dictionary 2Document1,066 pagesAmharic English Dictionary 2ShlomoNo ratings yet

- 1abdel Massih Ernest T A Computerized Lexicon of Tamazight PDFDocument474 pages1abdel Massih Ernest T A Computerized Lexicon of Tamazight PDFShlomoNo ratings yet

- Hebrew and Aramaic Substrata in Spoken PDFDocument22 pagesHebrew and Aramaic Substrata in Spoken PDFShlomoNo ratings yet

- The Fundamentals of AmharicDocument145 pagesThe Fundamentals of AmharicShlomo100% (2)

- Bosnian Croatian Serbian A Grammar With Sociolinguistic CommentaryDocument84 pagesBosnian Croatian Serbian A Grammar With Sociolinguistic CommentaryShlomoNo ratings yet

- 18 Introduction To Classical Ethiopic PDFDocument239 pages18 Introduction To Classical Ethiopic PDFElvis SantanaNo ratings yet

- Daf Ditty Pesachim 31: The Darker Side of MoneylendingDocument32 pagesDaf Ditty Pesachim 31: The Darker Side of MoneylendingJulian Ungar-SargonNo ratings yet

- The Dance of The SabbathDocument3 pagesThe Dance of The SabbathO9AREAPERNo ratings yet

- The Political Groups in The Time of JesusDocument22 pagesThe Political Groups in The Time of Jesusapi-263850753No ratings yet

- Midrash Toldoth Yeshu of Rabbi Yohanan Ben ZakaiDocument12 pagesMidrash Toldoth Yeshu of Rabbi Yohanan Ben ZakaiTiago Souza100% (1)

- Jesus-Believing Jews in AustraliaDocument30 pagesJesus-Believing Jews in AustraliaDvir AbramovichNo ratings yet

- Merkabah: For The Series of Israeli Main Battle Tanks, SeeDocument10 pagesMerkabah: For The Series of Israeli Main Battle Tanks, SeeChar Crawford0% (1)

- Rabbinic Authority English BibliographyDocument2 pagesRabbinic Authority English BibliographyYehudah DovBer ZirkindNo ratings yet

- Books Too Holy To PrintDocument8 pagesBooks Too Holy To PrintMike CedersköldNo ratings yet

- Delitzsch NT InfoDocument7 pagesDelitzsch NT Infoyosef28100% (1)

- Amidah PresentationDocument12 pagesAmidah PresentationAnnieCas100% (1)

- Yom Kippur ReviewDocument2 pagesYom Kippur ReviewNilia PustakaNo ratings yet

- When Ataturk Recited Shema Yisrael ''It's My Secret Prayer, Too,'' He ConfessedDocument4 pagesWhen Ataturk Recited Shema Yisrael ''It's My Secret Prayer, Too,'' He ConfessedΚαταρα του ΧαμNo ratings yet

- February 2018 Bulletin Low ResDocument16 pagesFebruary 2018 Bulletin Low ResAgudas Achim CongregationNo ratings yet

- 15878Document2 pages15878Tianlu WangNo ratings yet

- Appl1 2Document1 pageAppl1 2funmastiNo ratings yet

- Makom 2011.12.v.2Document3 pagesMakom 2011.12.v.2Rich WalterNo ratings yet

- Introduction To World Religions and Belief Systems: Quarter 1 - Module 4: JudaismDocument117 pagesIntroduction To World Religions and Belief Systems: Quarter 1 - Module 4: JudaismKristel GabrielNo ratings yet

- Juf Confidential Minutes 2019 PDFDocument32 pagesJuf Confidential Minutes 2019 PDFMondoweissNo ratings yet

- Martillaro p3 Final Draft 79051Document8 pagesMartillaro p3 Final Draft 79051api-438179045No ratings yet

- Ioliver 1Document596 pagesIoliver 1Gabi Mihalut100% (2)

- History of Finance: Babylonian EmpireDocument1 pageHistory of Finance: Babylonian EmpireMaika J. PudaderaNo ratings yet

- Anne Frank WorksheetDocument1 pageAnne Frank WorksheetIdinaNo ratings yet

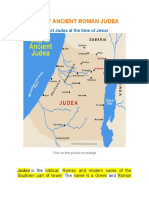

- Map of Ancient Roman JudeaDocument19 pagesMap of Ancient Roman JudeaDanica PascuaNo ratings yet

- Abraham Ben Samuel Cohen of Lask - WikipediaDocument1 pageAbraham Ben Samuel Cohen of Lask - WikipediaNyx Bella DarkNo ratings yet

- Do Mitzvot Need Kavanah?Document2 pagesDo Mitzvot Need Kavanah?outdash2No ratings yet

- Lesson 07 - Deriving The Laws IIIDocument11 pagesLesson 07 - Deriving The Laws IIIMilan KokowiczNo ratings yet

- The Magic of Thinking Big David J SchwartzDocument6 pagesThe Magic of Thinking Big David J SchwartzEricka Mabel CastilloNo ratings yet

- (Library of New Testament Studies) Kieran J. O'Mahony & Milltown Institute of Theology & Philosophy-Christian Origins - Worship, Belief and Society-Bloomsbury AcademicDocument281 pages(Library of New Testament Studies) Kieran J. O'Mahony & Milltown Institute of Theology & Philosophy-Christian Origins - Worship, Belief and Society-Bloomsbury AcademicBayram J. Gascot Hernández100% (2)

- Jesus Christ in The Talmud Midrash ZoharDocument176 pagesJesus Christ in The Talmud Midrash ZoharwinmortalisNo ratings yet

- Tsti June 09Document16 pagesTsti June 09Dan CohenNo ratings yet